Abstract

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) report fatigue more frequently than healthy population, but the precise mechanisms underlying its presence are unknown. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of fatigue in IBD and its relation with potential causative factors. A survey on fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and the presence of sarcopenia and malnutrition, was sent by email to 244 IBD outpatients of the Gastroenterology Unit of Academic Hospital of Padua. Demographics and clinical data, including the levels of fecal calprotectin (FC) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and current pharmacological treatments were obtained from patients’ medical records. Ninety-nine (40.5%) subjects answered the survey. Ninety-two (92.9%) patients reported fatigue, with sixty-six having mild to moderate fatigue and twenty-six severe fatigue. Multivariate analysis showed that abnormal values of CRP (OR 5.1), severe anxiety (OR 3.7) and sarcopenia (OR 4.4) were the factors independently associated with severe fatigue. Fatigue has a high prevalence in subject affected by IBD. Subjects with altered CRP, sarcopenia and severe anxiety appear more at risk of severe fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory diseases affecting the gastrointestinal tract1. IBD is a lifelong condition without a cure, and because of the chronicity of symptoms and progression to disability, particularly in CD, patients with IBD may experience impaired quality of life, psychological illness, including anxiety and depression, sleep disturbance, and fatigue2,3,4,5,6. Moreover, patients affected by IBD are subjected to a major risk of malabsorption and reduction of food intake7,8. Finally, IBD patients tend to have a sedentary lifestyle, although physical activity is not contraindicated in this population8. All these factors contribute to an increased risk of developing protein energy malnutrition and sarcopenia9.

Fatigue is defined as an “overwhelming sense of tiredness, reduced energy levels and feeling of exhaustion that is not responsive to prolonged rest or sleep”7,10. In people affected by IBD, fatigue has been reported by up to 80% of patients with active disease and up to 54% of patients in remission11 twice more common than healthy controls12, and it is commonly defined as the most debilitating symptom during the period of disease inactivity9,13. Fatigue impacts negatively on every day occupations, on concentration during social interaction and causes the suspension of physical activity14. The self-imposed restrictions caused by fatigue elicit feelings of anger, resentment, self-pity and sadness, causing worsening of the quality of life. Causal factors are unknown because of the multifactorial nature of the symptom13. When measured with functional scales, fatigue is more prevalent in young women, those who are physically inactive, with a short history of disease, and who declare feeling stressed, depressed, or anxious15,16,17. Moreover, fatigue has been linked with a sub clinical pro-inflammatory state; it seems in fact that the complex formed by IL-6 and the IL-6 receptor, as well as TNFα, causes a break in the blood–brain barrier with effects on the central nervous system, provoking fatigue, anxiety, and depression18. Corticosteroids have been also implicated in the genesis of fatigue, while anti-TNF therapy seems to be protective19. Finally, the presence of micro- or macro-intestinal blood leaks, iron malabsorption, the suppression of erythropoiesis and the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been associated with a high prevalence of anemia in IBD, partially correlated with the presence of fatigue11. However, to date, a clear causal relationship between fatigue and iron or other micronutrient deficiencies has not been established9,11,20.

An appealing hypothesis is that fatigue could be due to a reduction in lean mass, a condition caused by a combination of malabsorption, chronic inflammation and sedentary lifestyle8,14,15. Data supporting this theory come from the analysis of muscle strength and endurance indices in a sample of IBD patients, which showed a significant relation between asthenia and loss of muscle mass21.

This study aimed to examine the prevalence of fatigue in subject affected by IBD and its relationship with sarcopenia and other possible causative factors.

Methods

Study design

The present cross-sectional study was conducted at IBD Unit of Azienda Ospedaliera di Padova (Italy). Consecutively and prospectively, all IBD patients who visited our IBD Unit from February to July 2020 were asked to participate in this study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee of Padova University (protocol number 4197/AO/17). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

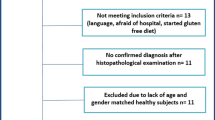

A survey was conducted sending out an email to 244 IBD outpatients. Inclusion criteria were: age over 18, a histologically-confirmed diagnosis of CD or UC for a least 6 months, and a recent outpatient encounter with the need to perform biochemical assessment of disease activity. Exclusion criteria included the presence of known psychiatric disorders, history of alcohol or drug abuse, pregnancy, neoplasia or other systemic disorders potentially influencing the psychological status (i.e. connective tissue disorders, fibromyalgia, diabetes mellitus, autonomic or peripheral neuropathy, and myopathy), and the lack of consent. Demographics and clinical data, including the levels of fecal calprotectin (FC) C-reactive protein (CRP), and current pharmacological treatments were obtained from patients’ medical records. For the purpose of the study, active disease was defined by the presence of FC values ≥ 250mcg/g and/or a value of Harvey Bradshaw Index > 4 for patients with CD and a partial Mayo score > 1 for patients with UC22,23. Moreover, abnormal CRP was considered when higher than 0.1 mg/dL.

The survey consisted of different questionnaires to be filled after initial formal and written approval of participation into this study. The time required to complete the questionnaire was approximately 45 min. The domains and questionnaires used were:

-

Fatigue assessment. To measure fatigue we used the IBD-F questionnaire, specifically developed for IBD patients13,24,25. The questionnaire is composed of two sections: the first examines the presence and the extent of fatigue, the second its impact on different aspects of daily living26. A score from 1 to 10 is suggestive of mild to moderate fatigue, a score from 11 to 20 of severe fatigue25.

-

Sarcopenia assessment. Due to SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we evaluated the presence of sarcopenia only through the SARC-F questionnaire, recommended by the European Consensus to elicit the declaration of sarcopenia’s signs and symptoms27. Indeed, there are five SARC-F components: strength, assistance with walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls. The scores range from 0 to 10, with 0 to 2 points for each component. Preliminary studies have suggested that a score equal to or greater than 4 is predictive of sarcopenia and poor outcomes.

-

Depression and anxiety assessment. Anxiety and depression were assessed via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a questionnaire validated for epidemiological and clinical studies28,29, which has been demonstrated to be reliable when applied to IBD patients19. The questionnaire is formed of two scales, each one composed of seven items. Normal scores for anxiety or depression are defined by a score less than 830,31. A subscore from 8 to 10 is defined as borderline abnormal, and a score from 11 to 21 as abnormal32.

-

Sleep disorders assessment. Sleep quality has been evaluated through the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, a questionnaire that examines seven different sleep components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, length, efficiency, sleep disturbances, drug use and daytime dysfunctions. The sum of each component gives a score from 0 to 21. A score of 5 or above suggests poor sleep quality33.

-

Quality of life assessment. Quality of life was measured through the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire Short Form34, specifically developed for testing subjects affected by these pathologies. It is widely validated, and has been demonstrated to be reliable and sensitive35. It is composed of ten questions, a subset of the full Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, graded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (a very severe problem) to 7 (not a problem at all)36. A maximum of 70 indicates the best IBD related quality of life, a minimum of 10 indicates the worst36.

-

Malnutrition assessment. Malnutrition was diagnosed according to the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition criteria, namely in the presence of a weight loss greater than the 5% within the past 6 months or a BMI < 20 if the subject was aged less than 70 years old, or a BMI < 22 if the subject was 70 years old or older, and the concomitant presence of active inflammatory disease or an abnormal value of CRP37.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We used univariate logistic regression models to assess whether demographic or IBD-related variables, HADS, IBDQ, PSQI, sarcopenia, or malnutrition were related to severe fatigue. Statistically significant variables in univariate analyses were then included in a multivariate regression model to identify, using the AIC stepwise method, independent risk factors for fatigue. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA 11 software was used to perform statistical analysis.

Ethics committee approval

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee of Padova University, Italy (protocol number 4197/AO/17).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Ninety-nine out of 244 (40.5%) IBD outpatients followed at our IBD unit and enrolled in the study, answered the survey by email. Table 1 summarizes the main demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. The mean age of subjects was 38.7 ± 13.9 years, there were 57.5% males and 54.5% patients affected by CD. Almost 50% had a duration of disease longer than 10 years. Among the entire population, 30% had clinically and/or biochemically active disease, 44% were taking biological therapies, and only 3% were on a corticosteroid.

Sarcopenia and malnutrition

According to the SARC-F questionnaire, 13 subjects were sarcopenic (13.1%), with a mean score of 1.4 ± 1.7. Among the participants, 25 were malnourished: 16 satisfied the phenotypic criteria showing a BMI < 20 (mean BMI of malnourished subjects with low BMI: 18.2 ± 1.2 kg/m2), and nine reported weight loss greater than the 5% in the past 6 months (mean weight loss 8.1 ± 5.8 kg).

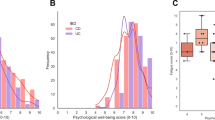

Depression, anxiety, sleep disorders and quality of life

After completing the HADS scale, 21 (21.2%) subjects had borderline abnormal anxiety scores and 32 (32.3%) abnormal anxiety scores, with an overall mean score of 7.9 ± 4.4. Twenty subjects had borderline abnormal depression scores and six abnormal depression scores, with a mean score of 4.9 ± 3.3. A condition of altered sleep quality was found in 62 subjects (62.6%, mean score 6.9 ± 6.6). Because of the absence of established cut-offs, scores from IBDQ-SF were divided into tertiles obtaining 35 (35.3%) subjects in the first tertile (worst quality of life, score 10–42), 37 (37.3%) subjects in the second (score 43–56), and 27 (27.2%) in the third (best quality of life, score 57–70) tertile. The mean IBDQ score value was 47.8 ± 13.6.

Fatigue: prevalence, severity and risk factors

The overall prevalence of fatigue in the sample was 92.9%, out of whom seven (7.1%) patients declared no fatigue, sixty-six (66.6%) had mild-to-moderate fatigue, and 26 (26.2%) had severe fatigue (Table 2).

Based on univariate analysis, we observed that patients with severe anxiety, borderline abnormal or abnormal depression scores, low QoL, sleep disturbances, sarcopenia, malnutrition, and abnormal CRP (> 0.1 mg/dL) were more likely to report severe fatigue (Table 2). In contrast, age, type of disease, sex, disease duration, medical therapies and fecal calprotectin were not associated with fatigue (Table 2). After multivariate regression, including all significant risk factors in univariate analysis, only abnormal CRP values (OR 5.1, 95% CI 1.3–20.2), severe anxiety (OR 3.7 95% CI 0.93–15) and sarcopenia (OR 4.4, 95% CI 1.1–20.1) were identified as risk factors for severe fatigue in IBD patients.

Discussion

Fatigue is a symptom characterized by an overwhelming sense of tiredness unresponsive to rest or sleep and causing frustration, absenteeism from work, reduction of activities and impairment of social life13. In subjects with IBD, fatigue is more prevalent than in a healthy population11, and is reported to be one of the worst symptoms during disease remission, determining higher levels of intestinal disease worries and concerns38. Evidences on its cause, prevalence and management are still uncertain39. Thus, this study was performed in order to increase our understanding on the prevalence of fatigue in patients with IBD and, at the same time, explore factors that might be associated with it. In particular, we evaluated whether muscle mass reduction could play a role in determining fatigue, in addition to the previously mentioned features. The results of our analysis show a high prevalence of fatigue in patients affected by IBD, represented by a sample composed mainly of young people with a long history of disease. We did not find any influence of sex, age, or disease duration on fatigue, whereas we found that fatigue was associated with altered CRP, severe anxiety and sarcopenia.

Our study population was mainly composed by young adults (mean age 38.7 ± 13.9 years). Nevertheless, despite their young age, the rate of subjects having sarcopenia was relevant. Sarcopenia is considered a relevant risk factor for functional age-related negative outcomes, including frailty and disability. Consistently, the parallel clinical evolution of sarcopenia and fatigue in such a young sample of patients with IBD may have important clinical implication since could represent an early alarm, in the perspective of future aging trajectories40.

Patients affected by IBD are subjected to a major risk of malabsorption7. This happens because the intestinal mucosa is not fully functional, especially when the disease is more active, because of the possible presence of complications such as fistulae, loss of mucosal absorptive surface, bowel resections, and because of the pharmacological therapies such as corticosteroids, which cause insulin resistance and leads to loss of calcium, vitamin D, albumin, and immunoglobulins41. Moreover, chronic inflammation and anorexia may increase energy expenditure and food intake10. In particular, sarcopenia is a condition of reduced muscle mass, strength, and function that impacts people affected by CD more than those affected by UC, with an estimated prevalence according to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) of 28% and 13%, respectively42. The loss of lean mass is more prevalent, and happens at younger age, in people affected by IBD than in healthy individuals43. Among our patients, overall prevalence of sarcopenia was 13%, less than that reported in the literature, probably because of limitations of the SARC-F in detecting severe sarcopenia27. Nevertheless, its prevalence and the association observed following multivariate regression analysis suggest that sarcopenia represents a major contributor to fatigue in some patients with IBD.

In contrast to other authors9,26,34, we did not find a different prevalence of severe fatigue between UC and CD or among patients using different pharmacological treatments. This could be due to the fact that in our cohort only a few patients were taking corticosteroids, the therapy most often associated with fatigue in previous studies. Concerning anti-TNF therapies, adalimumab was reported have no effect on fatigue in a Cochrane meta-analysis and data about vedolizumab were too limited to perform any sub-analysis39. Thus, their efficacy in relieving fatigue is still questionable, and our study is in line with this interpretation39. Consistent to what is reported in literature, we did not observe that severe fatigue was more frequent in subjects with active IBD (as defined by fecal calprotectin), but we found a higher risk in subjects with abnormal CRP, in keeping with the observation of higher levels of inflammatory mediators in subjects experiencing fatigue and depression44.

The study design does not allow to evaluate the inference of a causal relation between sarcopenia and fatigue. We can only hypothesize, as proposed in the theoretical framework, that fatigue could be caused by lean mass reduction, in turn maybe caused by malnutrition45, a condition which affected 25% of our sample. On the other hand, it is also possible that fatigue perception causes a reduction in physical activity and therefore a reduction of muscle mass, sustained by malnutrition. This is the main hypothesis behind a study analyzing the relationship between muscle loss and systemic lupus erythematosus—related fatigue in a small sample of patients. The authors observed, via MRI, a voluntary reduced muscle contraction in subjects perceiving higher exertion, concluding toward a sarcopenia driven by fatigue, rather than the opposite46. The two interpretations however, instead of opposite, could be seen as a self-powered vicious cycle. This finding is consistent with the literature concerning strategies to treat fatigue: physical activity has already been identified as a valid therapeutic intervention for different cancers47,48,49 and two exploratory studies showed promising effects in subjects affected by IBD39,50. In the first study, investigators prescribed individual advice to increase physical activity by 30%, with some suggestion of the efficacy of this intervention50. In the second study the intervention was composed of three sessions of 60 min of strength exercises for 26 consecutive weeks, resulting in an improvement in quality of life and lumbar bone mineral density, and a decrease of fatigue perception measured with the IBD-F questionnaire39.

Fatigue resulted significantly related with severe anxiety and borderline abnormal or abnormal depression scores, confirming its connection on patient’s mental wellbeing. Subjects experiencing fatigue were more likely to have abnormal anxiety and depression scores, sleep disorders and to have lower quality of life scores (whose prevalence in our sample was of the 73%). This latter relationship has been described by others19, and may be linked to the burden of living with a chronic disease38, or even a physiological response to inflammation mediated by cytokines30. Sleep disturbances are recurrent in subjects affected by IBD also suffering for anxiety and depression5, worsening patients’ quality of life5,51. Poor sleep quality has already been associated with fatigue20, and the compresence of these two symptoms is considered an alert to deepen not only the presence of psychological disorder, but also of the gastrointestinal disease activity51. These two variables, however, lost significance in the multivariate analysis. Previous literature described the existence of a bidirectional link between fatigue and psychological dysfunctions, indicate as realistic both the hypothesis of fatigue as causative factor and the idea that negative feelings, maladaptive behaviors, and negative perception about the symptoms can worsen the perception of it52.

Our multivariate model suggests that sarcopenia, altered CRP and severe anxiety were the only independent risk factors for severe fatigue. In particular, we observed that patient with altered CRP and sarcopenia had an 5.1 and 4.4 higher odds of reporting severe fatigue respectively, while patients with severe anxiety had an 3.7 higher risk of severe fatigue. This finding is in line with the results of Patino-Hernandez et al., who found, in a study performed in an elderly population, that sarcopenia was significantly related to fatigue and depression, but when adjusted for confounding, only fatigue was independently related to it53. The authors explained this phenomenon with the overlap of items between depression and fatigue measurement tools. In contrast, Norden et al. in a study on fatigue in tumor-bearing mice, observed that the animals developed fatigue and a depressive-like behavior prior to muscle loss, in this case caused by the presence of the tumor44. The authors pointed out depressive symptom as the first determinant in developing fatigue, with sarcopenia and the worsening of quality of life as the main consequences.

This study has some limits, first of all the diagnosis of sarcopenia was based only on the SARC-F questionnaire. The European Consensus stated clearly about the fact that strength exercises and muscle quantity measures represent the gold standard of sarcopenia assessment, and a more accurate study should conduct these procedures. However, due to the restrictions related to the risk of COVID transmission, we reduced access to the hospital for all patients and therefore more objective assessments were not possible. Moreover, the same pandemic affected our ability to recruit patients, thus resulting in a limited sample size, together with a lower response rate (40.5%) to the survey, as compared with other studies investigating fatigue by means of questionnaire (55%). Further, the cross-sectional design of this investigation did not allow us to establish if the presence of severe fatigue caused a low sarcopenia or vice versa. Despite the importance of the physical activity, we did not ask the patients about this in the survey. Lastly, diagnosis of active disease was not based on objective evidence like endoscopy or radiology, but on a fecal calprotectin value, although this is widely accepted as a good biomarker of disease activity in patients with IBD54. Nevertheless, the study suggests a connection between fatigue and sarcopenia. What is clear is that when studying a complex phenomenon like fatigue, it cannot be done without taking into account both physical and psychological health.

In conclusion, we confirm that fatigue is a symptom with a high prevalence in subjects affected by IBD and sarcopenia, a condition caused by malnutrition and the state of chronic inflammation typical of these patients, is an important risk factor for it. Moreover, we observed a higher prevalence of severe fatigue in subjects with severe anxiety. Thus, subjects affected by IBD should be asked about the presence of fatigue during clinical evaluation, above all in case of concomitant symptoms such as anxiety, depression or bad sleep quality, and they should eventually be referred to a professional for a consultation. The role of physical activity in protecting from fatigue seems promising and should be encouraged, when considered appropriated, because of its role in preventing lean mass loss and therefore maintaining individuals’ autonomy, preventing from hospitalization and improving quality of life. Further research on the underlying causes of fatigue, as well as effective interventions to treat it, are needed.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kemp, K. et al. Second N-ECCO consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 12, 760–776 (2018).

Marinelli, C. et al. Factors influencing disability and quality of life during treatment: A cross-sectional study on IBD patients. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–10 (2019).

Barberio, B., Zamani, M., Black, C. J., Savarino, E. V., & Ford, A. C. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6(5), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00014-5 (2021).

Barberio, B., Zingone, F. & Savarino, E. V. Inflammatory bowel disease and sleep disturbance: As usual, quality matter. Dig. Dis. Sci. 66, 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06268-5 (2021).

Marinelli, C. et al. Sleep disturbance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prevalence and risk factors: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 10, 507 (2020).

Hyphantis, T. N. et al. Psychological distress, somatization, and defense mechanisms associated with quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 55, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0762-z (2010).

Bianchi, M. L. Inflammatory bowel diseases, celiac disease, and bone. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 503, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.026 (2010).

Otto, J. M. et al. Preoperative exercise capacity in adult inflammatory bowel disease sufferers, determined by cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 27, 1485–1491 (2012).

Bamba, S. et al. Sarcopenia is a predictive factor for intestinal resection in admitted patients with Crohn’s disease. PLoS ONE 12, 1–12 (2017).

Balestrieri, P. et al. Nutritional aspects in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nutrients 12, 372 (2020).

Borren, N. Z., van der Woude, C. J. & Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Fatigue in IBD: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0091-9 (2019).

Nocerino, A. et al. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel diseases. Etiologies https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01151-w (2019).

Hindryckx, P. et al. Unmet needs in IBD: The case of fatigue. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 55, 368–378 (2018).

Beck, A. et al. How fatigue is experienced and handled by female outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2013, 1–10 (2013).

Aluzaite, K. et al. Detailed multi-dimensional assessment of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 3, 192–202 (2018).

Ratnakumaran, R. et al. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease reflects mood and symptom-reporting behavior rather than biochemical activity or anemia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 1165–1167 (2018).

O’Connor, A. et al. Randomized controlled trial: A pilot study of a psychoeducational intervention for fatigue in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 10, 204062231983843 (2019).

Lee, C. H. & Giuliani, F. The role of inflammation in depression and fatigue. Front. Immunol. 10, 1696 (2019).

Chavarría, C. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicentre study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 996–1002 (2019).

Taft, T. H. et al. Psychological considerations and interventions in inflammatory bowel disease patient care. Gastroenterol. Clin N. Am. 46, 847–858 (2017).

Pizzoferrato, M. et al. Characterization of sarcopenia in an IBD population attending an italian gastroenterology tertiary center. Nutrients 11, 2281 (2019).

Harvey, R. F. & Bradshaw, J. M. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet 315, 514 (1980).

Lewis, J. D. et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the mayo score to assess clinical response in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 14, 1660–1666 (2008).

Norton, C. et al. Assessing fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: Comparison of three fatigue scales. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther 42, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13255 (2015).

Czuber-Dochan, W. et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J. Crohn’s Colitis 8, 1398–1406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.013 (2014).

Saraiva, S. et al. Evaluation of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: A useful tool in daily practice. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 54, 465–470 (2019).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48, 16–31 (2019).

Costantini, M. et al. Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: Validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer 7, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005200050241 (1999).

Iani, L., Lauriola, M. & Costantini, M. A confirmatory bifactor analysis of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in an Italian community sample. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 12, 1–8 (2014).

Smarr, K. L. & Keefer, A. L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionna. Arthritis Care Res. 63, 454–466 (2011).

Julian, L. J. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care 63, 1–11 (2011).

Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10, 1–11 (2003).

Mollayeva, T. et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 25, 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.009 (2016).

Ciccocioppo, R. et al. Validation of the Italian translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Dig. Liver Dis. 43, 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2010.12.014 (2011).

Chen, X. L. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments: A systematic review of measurement properties. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15, 1–13 (2017).

Lam, M. Y. et al. Validation of interactive voice response system administration of the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 15, 599–607 (2009).

Cederholm, T. et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 38, 1–9 (2019).

Jelsness-Jørgensen, L. P. et al. Chronic fatigue is associated with increased disease-related worries and concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 445–452 (2012).

Jones, K. et al. Randomised clinical trial: Combined impact and resistance training in adults with stable Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 52, 964–975 (2020).

Bellone, F. et al. Fatigue, sarcopenia, and frailty in older adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Minerva Gastroenterol. 1, 1–10 (2021).

Pascual, V. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease: Overlaps and differences. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 4846–4856 (2014).

Bischoff, S. C. et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 39, 632–653 (2020).

Pedersen, M., Cromwell, J. & Nau, P. Sarcopenia is a predictor of surgical morbidity in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 1867–1872 (2017).

Norden, D. M. et al. Tumor growth increases neuroinflammation, fatigue and depressive-like behavior prior to alterations in muscle function. Brain Behav. Immun. 43, 76–85 (2015).

Sieber, C. C. Malnutrition and sarcopenia. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 793–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01170-1 (2019).

Cheung, S. M. et al. Metabolic and structural skeletal muscle health in systemic lupus erythematosus-related fatigue: A multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Care Res. 71, 1640–1646 (2019).

van Vulpen, J. K. et al. Effects of physical exercise during adjuvant breast cancer treatment on physical and psychosocial dimensions of cancer-related fatigue: A meta-analysis. Maturitas 85, 104–111 (2016).

Witlox, L. et al. Four-year effects of exercise on fatigue and physical activity in patients with cancer. BMC Med. 16, 1–9 (2018).

Kampshoff, C. S. et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: Results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0513-2 (2015).

Mcnelly, A. S. et al. P531 Inflammatory bowel disease and fatigue: The effect of physical activity and/or omega-3 supplementation. J. Crohn’s Colitis 10, S370–S371 (2016).

Canakis, A. & Qazi, T. Sleep and fatigue in IBD: An unrecognized but important extra-intestinal manifestation. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 22, 1–10 (2020).

Artom, M. et al. The contribution of clinical and psychosocial factors to fatigue in 182 patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 45, 403–416 (2017).

Patino-Hernandez, D. et al. Association of fatigue with sarcopenia and its elements: A secondary analysis of SABE-Bogotá. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 3, 233372141770373 (2017).

Ikhtaire, S. et al. Fecal calprotectin: Its scope and utility in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. 51, 434–446 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T., E.S.: design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing of the manuscript, approving final version; P.B., B.B., A.C.F., F.Z.: data analysis, writing of the manuscript, approving final version. All authors commented on drafts of the paper. All authors have approved the final draft of the manuscript. Guarantor of the article: L.T., E.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ES has received lecture or consultancy fees from Abbvie, Alfasigma, Amgen, Aurora Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EG Stada Group, Fresenius Kabi, Grifols, Janssen, Johnson&Johnson, Innovamedica, Malesci, Medtronic, Merck & Co, Novartis, Reckitt Benckiser, Sandoz, Shire, SILA, Sofar, Takeda, Unifarco; LT, FZ, BB, RV, PB, ACF, MS, IA, MF have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tasson, L., Zingone, F., Barberio, B. et al. Sarcopenia, severe anxiety and increased C-reactive protein are associated with severe fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Sci Rep 11, 15251 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94685-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94685-5

This article is cited by

-

Depression and active disease are the major risk factors for fatigue and sleep disturbance in inflammatory bowel disease with consequent poor quality of life: Analysis of the interplay between psychosocial factors from the developing world

Indian Journal of Gastroenterology (2024)

-

Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in patients with ulcerative colitis in China: a cross-sectional study

BMC Gastroenterology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.