Abstract

This study investigated the association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with sleeping and developmental problems in 1-year-old infants. We used data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study, which registered 103,062 pregnancies between 2011 and 2014. Participants were asked about their sleep habits prior to and during pregnancy. Follow-up assessments were conducted to evaluate the sleep habits and developmental progress of their children at the age of 1 year. Development during infancy was evaluated using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ). Maternal short sleep and late bedtime before and during pregnancy increased occurrence of offspring’s sleeping disturbances. For example, infants whose mothers slept for less than 6 h prior to pregnancy tended to be awake for more than 1 h (risk ratio [RR] = 1.49, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.34–1.66), sleep less than 8 h during the night (RR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.44–1.79), and fall asleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.26–1.40). Only subjective assessments of maternal sleep quality during pregnancy, such as very deep sleep and feeling very good when waking up, were inversely associated with abnormal ASQ scores in 1-year-old infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep duration among the general population in Japan has been reported to be shorter than that in other countries1 and has become even shorter in recent years2. Furthermore, it has been reported that approximately 10% of infants have sleeping problems3. Neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), neurodevelopment abnormalities, and disturbed sleep habits, such as late bedtime and intense night crying, are observed in early infancy4. The incidence of developmental disorders is increasing in developed countries, including Japan5,6,7. Factors related to developmental disorders include genetic ones and environmental (in utero) ones8,9. Maternal lifestyle such as sleep pattern may affect the offspring’s sleep and development.

It has been reported that maternal sleep disorders are associated with developmental progress in the offspring. For example, maternal sleep disordered breathing (SDB) during pregnancy is associated with the offspring’s development, manifesting as disrupted social skills and low reading-test scores10,11. Thus, not only maternal sleep habit but also maternal sleep disorders during pregnancy may be related to early infant sleep patterns and development. However, no large-scale study has examined the potential associations between maternal sleep and the offspring’s sleep patterns or development. Additionally, the importance of maternal sleep during various periods of pregnancy and the persistence of the influence remain unclear.

We previously reported that maternal sleep habits, such as short sleep duration and late bedtime, both before and during pregnancy, were associated with the offspring’s sleep problems and temperament at 1 month of age12. We hypothesize that maternal sleep before and during pregnancy would continue to be associated with the infant’s sleep and developmental problems even at 1 year of age.

This study aimed to expand on those findings and investigate the association between maternal sleep habits, before and during pregnancy, with offspring outcomes at 1 year of age.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the participants, along with the available data on sleep duration before pregnancy, are shown in Table 1. The characteristics of participants in the various sleep groups are also shown in Supplemental Table 1. The reported sleep duration was on average between 7 and 8 h, both before and during pregnancy. The participants tended to sleep longer and go to bed earlier during pregnancy than before pregnancy. Significant data points are summarized below and include risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in the multivariable model, adjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational age at birth, parity, infertility treatment, and infant sex.

Maternal sleep before pregnancy and infant sleep (Table 2)

Short sleep duration less than 6 h before pregnancy was associated with a higher risk of night waking for ≥ 1 h (RR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.34–1.66), sleeping for < 8 h at night (RR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.44–1.79), and falling sleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.26–1.40) in the offspring, compared to offspring of mothers who slept for 7–8 h. On the contrary, compared to offspring of mothers who slept for 7–8 h, the offspring of mothers who slept for more than 10 h before pregnancy were also at a higher risk of night waking for > 1 h (RR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.09–1.44) and sleeping for < 8 h at night (RR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.09–1.46). Compared to offspring of mothers who slept before midnight before pregnancy, offspring of mothers who slept after midnight had a higher risk of night waking for > 1 h (RR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.30–1.47), sleeping for < 8 h at night (RR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.22–1.40), and falling asleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.48–1.58).

In the sub-analysis limited to participants who slept for 7–9 h during pregnancy, we found similar associations between maternal sleep before pregnancy and the offspring’s sleep outcome (Supplemental Table 2). Maternal sleep for < 6 h increased the risk ratio of infants wakening for more than 1 h, sleeping for < 8 h during the night, and falling asleep at 22:00 or after. Maternal sleep for more than 10 h also increased the risk ratio of infants awakening for > 1 h and sleeping for < 8 h during the night. Maternal bedtime after midnight increased the risk ratio of infants awakening > 1 h, sleeping < 8 h, and falling asleep at 22:00 or later.

Maternal sleep during pregnancy and infant sleep (Table 3)

As for the analysis of maternal sleep before pregnancy, short or long sleep duration and sleeping after midnight during pregnancy were associated with a higher risk of some sleep outcomes. Infants whose mothers slept for less than 6 h during pregnancy tended to be awake for > 1 h at night (RR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.35–1.72), to sleep for < 8 h during night (RR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.48–1.88), and to sleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.31–1.47), compared to the infants whose mother slept for 7–8 h. On the contrary, compared to the offspring of mothers who slept for 7–8 h, offspring of mothers who slept for more than 10 h during pregnancy tended to sleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.15). Maternal bedtime after midnight during pregnancy was also associated with a higher risk of infants night waking for > 1 h (RR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.32–1.51), sleeping for < 8 h at night (RR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.32–1.51), falling asleep at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.53–1.63), and frequency of crying (RR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.15), compared to the group of maternal bedtime before midnight.

In the sub-analysis limited to the participants who slept for 7–9 h before pregnancy, we found similar associations between maternal sleep during pregnancy and infants’ sleep outcome (Supplemental Table 2). Maternal sleep for less than 6 h and for more than 10 h increased the risk ratio of falling asleep at 22:00 or after. Maternal bedtime after midnight increased the risk ratio of infants awakening for > 1 h at night, sleep < 8 h at night, and falling asleep at 22:00 or later.

Subjective items of sleep during pregnancy were also associated with the offspring’s sleeping problems. For example, maternal “very light” sleep was associated with a higher risk of 3 or more waking instances in a night (RR = 1.74, 95% CI 1.47–2.06), night waking for more than 1 h (RR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.11–1.39), sleeping for less than 8 h at night (RR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.23–1.55), sleeping at 22:00 or later (RR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.15), crying 5 days or more in a week (RR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.38–1.67), compared to the group of maternal “normal” sleep depth.

Maternal sleep and offspring developmental progress

We used the Japanese version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, third edition (J-ASQ-3), to evaluate the offspring’s development. There were no associations between sleep duration or bedtime, both before and during pregnancy, and abnormal J-ASQ-3 scores (Table 4). However, “good” and “very good” feelings when waking up during pregnancy were associated with a lower risk of abnormal J-ASQ-3 scores for any one of the five domains in a multivariable model (RR for good vs. normal = 0.86, 95% CI 0.81–0.91; RR for very good feeling vs. normal = 0.81, 95% CI 0.69–0.95) (Table 5), compared to the group of maternal “normal” feelings at waking up. Moreover, for the depth of sleep during pregnancy, “very deep” sleep decreased the risk of abnormal J-ASQ-3 scores (RR for very deep vs. normal = 0.83, 95% CI 0.71–0.98), compared to the group of maternal “normal” sleep depth.

Discussion

This study investigated whether maternal sleep before and during pregnancy was associated with sleeping or developmental problems in 1-year-old infants, using data from a nationwide large-scale cohort study in Japan. The present study showed that maternal short or long sleep and bedtime after midnight, both before and during pregnancy, increased the risk ratio of the offspring’s sleeping problems at 1 year of age. The sub-analysis limited to participants with adequate sleep durations showed that maternal sleep pattern both before and during pregnancy was associated with the infants’ sleep outcomes. In addition, maternal subjective deep sleep and good mood at waking up during pregnancy were inversely associated with the infants’ sleep problems and the J-ASQ abnormal scores.

In this study, the participants tended to sleep longer and go to bed earlier during pregnancy than they did before pregnancy. In Japan, many women still stop working due to pregnancy or take maternity leave during late pregnancy. For that reason, sleep duration and bedtime might improve during pregnancy.

Sleep cycle develops from the fetal period13. Animal studies have shown that the circadian rhythm is affected by maternal life rhythms via endogenous substances such as melatonin14,15. Animal studies have also reported that exposure to sleep deprivation or artificial disappearance of light–dark cycle during pregnancy affects the offspring’s circadian rhythm abnormality and abnormal behavioral pattern16,17. In this study, mother’s short sleep and late bedtime were associated with the offspring’s sleeping problems, in part, because of the influence of maternal life rhythm during the fetal period.

In addition, it is considered that postpartum sleep pattern would partly correlate with sleep pattern before or during pregnancy. The study of 18-month-old twin infants reported that the genetic effect on sleep duration was 30.8% and the environmental effect was 64.1%18. The association between sleep before or during pregnancy and infant sleeping problems may be influenced via life rhythm after childbirth.

Subjective sleep quality was associated not only with infants’ sleep problem but also with the risk of abnormal ASQ scores. Subjective light sleep and bad mood upon wakening may reflect maternal SDB or depression19,20. Furthermore, it has been reported that both of these factors are related to the offspring’s development10,21. One potential factor explaining the association between maternal sleep and the offspring’s outcomes is inflammation. SDB and maternal depression increase inflammatory cytokine levels22,23,24; maternal inflammation during pregnancy can cause developmental disorders25,26. In addition, maternal SDB may affect the offspring’s development via low birth weight, which has been reported to be associated with neurodevelopment27,28. Interventions in maternal SDB and depression during pregnancy may improve subjective sleep quality and subsequent offspring sleep and development.

We have previously reported that maternal sleep habits, such as short sleep and late bedtime, before and during pregnancy, increased the risk ratio of long sleep duration during the day, bad mood, frequency of crying for a long time, and intense crying in 1-month-old offspring12. We further showed the association between maternal unsuitable sleep habits and the offspring’s non-desirable sleep habits as lasting even 1 year after birth. It is expected that children’s sleep and development will be influenced more by factors after birth than by prenatal ones. Therefore, it is important to clarify how long maternal sleep habits both before and during pregnancy are related to offspring’s sleep and developmental progression and to verify whether an intervention of maternal sleep, at any time point, improves offspring’s sleep and developmental outcomes.

This study was not without limitations. Because the present study was an observational study, confounding factors, such as parental life rhythm, that were not part of our evaluations might have been present. Moreover, information regarding both maternal sleep habits and infant’s outcomes was collected using a self-reported questionnaire, and thus, it had a risk of bias, such as a recall bias. The questions about maternal and infant sleep have not been previously validated. For example, we used the frequency of infant’s night crying as outcome, but we could not get the intended information about the duration and reason for the infant crying. Thus, there could be some bias, such as reporting bias. Additionally, about 13% of the participants were excluded from the analysis due to lack of information about exposure, covariates, and outcomes, and this group tended to be younger and with more smokers than the mothers who responded. This may be an added bias. In addition, because each association between maternal sleep and outcomes was tested separately, multiple testing may be a limitation. However, a strong point of this study is that our results were derived from large-scale nationwide data. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other study of this size on how maternal sleep during pregnancy correlates with offspring sleep behavior.

In conclusion, maternal short or long sleep duration and late bedtime, both before and during pregnancy, may increase sleeping problems such as late bedtime, awakening during night, and short sleep in 1-year-old offspring. Additionally, subjective maternal deep sleep and good mood at waking up during pregnancy decreased the risk ratio of infants’ sleeping problem and the ASQ abnormal scores.

Methods

Research ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ministry of Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and by the Ethics Committee of all participating institutions: the National Institute for Environmental Studies that leads the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), the National Center for Child Health and Development, Hokkaido University, Sapporo Medical University, Asahikawa Medical College, Japanese Red Cross Hokkaido College of Nursing, Tohoku University, Fukushima Medical University, Chiba University, Yokohama City University, University of Yamanashi, Shinshu University, University of Toyama, Nagoya City University, Kyoto University, Doshisha University, Osaka University, Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Hyogo College of Medicine, Tottori University, Kochi University, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kyushu University, Kumamoto University, University of Miyazaki, and University of Ryukyu. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Study participants

The data used in this study were obtained from the JECS, an ongoing large-scale cohort study. The JECS elucidated environmental factors that are associated with children’s health and development, and was designed to follow women through their pregnancy until their newborns grow up to be 13 years old. The participants were recruited between 2011 and 2014 from 15 regions throughout Japan, and the follow-up was mainly conducted via a self-administered questionnaire. The detailed protocol has been reported elsewhere29. The baseline profiles of participants of the JECS have been reported previously30. Participants answered a questionnaire about lifestyle and behavior twice during pregnancy. The questionnaire answered at recruitment was M-T1 and answered later during mid and late pregnancy was M-T2. The mean gestational weeks (SD, 5–95 percentile) at the time of answering M-T1 and M-T2 were 16.4 (8.0, 9–29) and 27.9 (6.5, 25–35) weeks, respectively. Participants also answered a questionnaire about their offspring 1 year after delivery (C-1y).

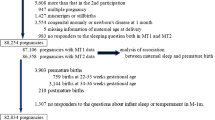

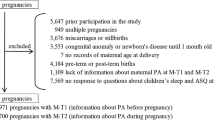

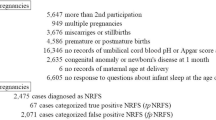

We excluded cases of multiple pregnancies (n = 949), preterm or post-term deliveries (before 37 weeks or after 42 weeks of gestation) (n = 4184), and congenital anomalies identified before 1 month of age (n = 3553). These factors are thought to be associated with infant development. For women who participated in the JECS study multiple times, data from the second and subsequent participations were excluded (n = 5647). In addition, we excluded cases for which information required for analysis was not available: miscarriage or stillbirth (n = 3676), missing information on maternal age at delivery (n = 7), lack of information about covariates (n = 450), incomplete information on maternal sleep at both M-T1 and M-T2 (n = 3376), missing responses to all questions about children’s sleep habits and developmental progress at C-1y (n = 7393).

The remaining 73,827 participants were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). To determine the risk of potential bias due to missing data, we compared the background characteristics between the population analyzed and the population excluded from analysis due to a lack of information about covariates and non-response to any questions about maternal sleep or children’s sleep and development (Supplemental Table 3). The group excluded from the analysis had more participants who were less than 25 years old and had smoking habits, lower educational background, and lower household income.

Maternal sleep

The categorization of maternal sleep was done as in our previous research12.

In the M-T1 questionnaire, participants were asked about their awakening time and bedtime before pregnancy. We calculated the sleep duration of participants and divided the participants into six groups according to sleep time: < 6 h, 6–7 h, 7–8 h (reference), 8–9 h, 9–10 h, and > 10 h. Participants were also divided by bedtime: 9.00 p.m. to midnight (reference), midnight to 3.00 a.m., and others (sleep before 9.00 p.m. or after 3.00 a.m.). The bedtime for more than 95% of the analyzed subjects was between 21:00 and 27:00. Since the mode of bedtime was between 22:00 and 24:00, we further divided the participants by bedtime 24:00.

In the M-T2 questionnaire, participants were asked about their usual awakening time and bedtime in the last month. The participants were divided into groups as described above for M-T1. Furthermore, the M-T2 questionnaire included two additional questions regarding sleep quality. One was “How would you rate your average depth of sleep during the past month?” The other one was “How would you rate your overall feeling when waking up in the morning, during the past month?” The answers to both questions were scored on a 1–5 scale, representing very light/bad, relatively light/bad, normal (reference), relatively deep/good, and very deep/good, respectively. Both of these questionnaires (M-T1 and M-T2) have not been previously validated.

Outcome 1: offspring’s sleeping problems

One year after delivery, information on infant sleep habits and crying at night was collected via a parent-reported questionnaire (C-1y). The participants answered their infant sleep time in the last 24 h in 30-min increments. They were also asked whether their children cried at night over the last month, and if so, the frequency (“rarely”, “1–3 times in a month”, “1–2 times in a week”, “3–4 times in a week”, “5 times in a week or more”). The questionnaires used for this outcome have not been previously validated. In this analysis, we focused on five points. First, from the responses regarding the infant’s sleep the day before, we determined the number of nocturnal awakenings. A previous study reported that the upper limit of the number of awakenings during the night is 2.5 for 1-year-old infants31; as such, we defined ≥ 3 awakenings as too many. Second, we analyzed whether the infants awoke more than once and whether they stayed awake for more than 1 h during the night. Third, we analyzed the duration of nocturnal sleep (from 20:00 to 07:59). We regarded less than 8 h of sleep as unusual. Fourth, we collected information regarding the infants’ bedtime. Based on previous studies32,33, we defined bedtime after 22:00 as too late. Fifth, we analyzed nocturnal crying frequency during the past month. If the mother answered that her infant awoke and cried during the night, and that the frequency of crying at night was more than five times per week, we defined the case as “crying at night”.

Offspring’s development

We used the J-ASQ-3 to evaluate offspring’s development. The C-1y questionnaire included a J-ASQ-3 assessment. J-ASQ-3 captures any developmental delay in five domains: communication, gross motor skills, fine motor skills, problem solving, and personal–social characteristics. The answer to each question is one of the following: “yes,” “sometimes,” or “not yet.” Scores are 10, 5, and 0 points, respectively. Each J-ASQ-3 domain was composed of six questions, and the total score ranged from 0 to 60. Higher scores were defined as more developed, and the cutoff points for every domain in the Japanese version were determined by a previous study34. We defined outcomes by whether the score was less than the determined cut-off point of each J-ASQ-3 domain and whether the score was less than the cutoff point of any one of the five J-ASQ-3 domains.

Covariates

Information about maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), parity, gestational age at birth, infertility treatment, and infant sex, was collected via self-administered questionnaires and/or medical records. These selected covariates were reported as risk factors for developmental disorders35,36,37.

Statistical analyses

We used a log-binominal regression model to explore the association of maternal sleep with each outcome and to estimate the RRs of each outcome and 95% CIs. We initially adjusted for maternal age at delivery and then further adjusted for smoking habits (never smoked, ex-smokers who quit before pregnancy, smokers during early pregnancy), alcohol consumption (never drinkers, ex-drinkers who quit before pregnancy, drinkers during early pregnancy), pre-pregnancy BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, ≥ 25.0 kg/m2), parity (0, ≥ 1), infertility treatment (no ovulation stimulation/artificial insemination by sperm from husband, assisted reproductive technology), gestational age at birth (37–38, 39–41 weeks), and infant sex (boys, girls). In this study, we did not actively complete any missing data, and all analysis was limited to data from those participants who provided complete information for exposures, outcomes, and covariates. In addition, we performed a sub-analysis twice to evaluate which maternal sleep, the one before or one during pregnancy, impacts the infant’s sleep outcome. In the first sub-analysis, we limited it to the participant groups with adequate sleep duration of 7–9 h during pregnancy and investigated the association between maternal sleep before pregnancy and infant’s sleep. We limited the second analysis to the participant groups with sleep duration of 7–9 h before pregnancy and examined the association between maternal sleep during pregnancy and infant’s sleep.

These statistical analyses were almost the same as those used in our previous study12.

In this study, we used a fixed dataset “jecs-an-20180131,” which was released in March 2018. Stata version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

References

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Special focus: Measuring leisure in OECD countries 19. Chapter 2. Special Focus: Measuring Leisure in OECD Countries. page 28. Figure 2.5. Sleep time on an average day in minutes. https://www.oecd.org/berlin/42675407.pdf (2009).

Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Survey on time use and leisure activities in 2016: Summary of results (QuestionnaireA). Time Use. 1. Distribution of daily time use. page 2. Figure 1. Time use for each major kind of activity by sex (1996-2016) – weekly average. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/2016/pdf/timeuse-a2016.pdf (2016).

Byars, K. C., Yolton, K., Rausch, J., Lanphear, B. & Beebe, D. W. Prevalence, patterns, and persistence of sleep problems in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics 129, e276–e284 (2012).

Zwaigenbaum, L. et al. Clinical assessment and management of toddlers with suspected autism spectrum disorder: Insights from studies of high-risk infants. Pediatrics 123, 1383–1391 (2009).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. Number of students taking special classes in 2014. page 1. Figure. Changes in the number of students taking special class from 1993 to 2014 (in Japanese). https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/tokubetu/material/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2015/03/27/1356210.pdf.

Schendel, D. E. & Thorsteinsson, E. Cumulative incidence of autism into adulthood for birth cohorts in Denmark, 1980–2012. JAMA 320, 1811–1813 (2018).

Zablotsky, B. et al. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 144, 2009–2017 (2019).

Bertrand, J. et al. Prevalence of autism in a United States population: The Brick Township, New Jersey, investigation. Pediatrics 108, 1155–1161 (2001).

Herbert, M. R. Contributions of the environment and environmentally vulnerable physiology to autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 23, 103–110 (2010).

Bassan, H. et al. The effect of maternal sleep-disordered breathing on the infant’s neurodevelopment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212(656), e1-656.e7 (2015).

Sun, Y., Hons, B., Cistulli, P. A. & Hons, M. Childhood health and educational outcomes associated with maternal sleep apnea: A population record-linkage study. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx158 (2017).

Nakahara, K. et al. Association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with preterm birth and early infant sleep and temperament. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Mirmiran, M., Maas, Y. G. H. & Ariagno, R. L. Development of fetal and neonatal sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep Med. Rev. 7, 321–334 (2003).

Reppert, S. M. & Schwartz, W. J. Maternal endocrine extirpations do not abolish maternal coordination of the fetal circadian clock*. Endocrinology 119, 1763–1767 (1986).

Serón-Ferré, M. et al. Impact of chronodisruption during primate pregnancy on the maternal and newborn temperature rhythms. PLoS ONE 8, e57710 (2013).

Radhakrishnan, A., Aswathy, B. S., Kumar, V. M. & Gulia, K. K. Sleep deprivation during late pregnancy produces hyperactivity and increased risk-taking behavior in offspring. Brain Res. 1596, 88–98 (2015).

Pires, G. N. et al. Effects of sleep modulation during pregnancy in the mother and offspring: Evidences from preclinical research. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13135 (2020).

Brescianini, S. et al. Genetic and environmental factors shape infant sleep patterns: A study of 18-month-old twins. Pediatrics 127, e1296–e1302 (2011).

Pamidi, S. & Kimoff, R. J. Maternal sleep-disordered breathing. Chest 153, 1052–1066 (2018).

Chong, Y.-S. et al. Associations between poor subjective prenatal sleep quality and postnatal depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 202, 91–94 (2016).

Gentile, S. Prenatal antidepressant exposure and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. Are we looking at the fall of Gods?. J. Affect. Disord. 182, 132–137 (2015).

Blair, L. M., Porter, K., Leblebicioglu, B. & Christian, L. M. Poor sleep quality and associated inflammation predict preterm birth: Heightened risk among African Americans. Sleep 38, 1259–1267 (2015).

Okun, M. L., Luther, J. F., Wisniewski, S. R. & Wisner, K. L. Disturbed sleep and inflammatory cytokines in depressed and nondepressed pregnant women. Psychosom. Med. 75, 670–681 (2013).

Huang, E. et al. Maternal prenatal depression predicts infant negative affect via maternal inflammatory cytokine levels. Brain. Behav. Immun. 73, 470–481 (2018).

Schobel, S. A. et al. Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10, 643–660 (2014).

Estes, M. L. & McAllister, A. K. Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 353, 772–777 (2016).

Hediger, M. L., Overpeck, M. D., Ruan, W. J. & Troendle, J. F. Birthweight and gestational age effects on motor and social development. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 16, 33–46 (2002).

Brener, A. et al. Mild maternal sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy and offspring growth and adiposity in the first 3 years of life. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

Kawamoto, T. et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health 14, 25 (2014).

Michikawa, T. et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). J. Epidemiol. 28, 99–104 (2018).

Galland, B. C., Taylor, B. J., Elder, D. E. & Herbison, P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: A systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 16, 213–222 (2012).

Nakahara, K. et al. Non-reassuring foetal status and sleep problems in 1-year-old infants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study: A cohort study. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–7 (2020).

Kitamura, S. et al. Association between delayed bedtime and sleep-related problems among community-dwelling 2-year-old children in Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 34, 11–14 (2015).

Mezawa, H. et al. Psychometric profiles of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Japanese translation. Pediatr. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13990 (2019).

Hua, J. et al. The prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors for children’s developmental coordination disorder: A population study in mainland China. Res. Dev. Disabil. 35, 619–625 (2014).

van Hoorn, J. F. et al. Risk factors in early life for developmental coordination disorder: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14781 (2020).

Wang, C., Geng, H., Liu, W. & Zhang, G. Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors associated with autism: A meta-analysis. Medicine. (United States) 96, 1–7 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants of this study and all the individuals involved in data collection. The idea of this work was obtained from other works supported by RIKEN Healthcare and Medical Data Platform Project and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers: JP16H01880, JP16K13072, JP18H00994, JP18H03388).

Funding

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Ministry of the Environment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study conception and design: S.M. Statistical analyses: T.M. Drafting of the manuscript and approval of the initial content: K.N., S.M., and T.M. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and manuscript review: K.N., T.M., S.M., M.O., K.K. (Kiyoko Kato), M.S. (Masafumi Sanefuji), E.S., M.T., M.S. (Masayuki Shimono), T.K., S.O., K.K. (Koichi Kusuhara), and JECS Group members.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakahara, K., Michikawa, T., Morokuma, S. et al. Association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with sleep and developmental problems in 1-year-old infants. Sci Rep 11, 11834 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91271-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91271-7

This article is cited by

-

Insomnia During the Perinatal Period and its Association with Maternal and Infant Psychopathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Current Psychiatry Reports (2023)

-

Longitudinal associations of DNA methylation and sleep in children: a meta-analysis

Clinical Epigenetics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.