Abstract

Preconception care (PCC) increases the chance of couple’s being healthy and having a healthier baby. It is an important strategy to prevent maternal and perinatal complications. The level of knowledge on preconception care increases its uptake. It is also considered as an input for further intervention of reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality enabling progress towards sustainable development goals (SDGs). Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled knowledge level of PCC and its association with family planning usage among women in Ethiopia. All observational studies regardless of publication status were retrieved. Important search terms were used to search articles in Google scholar, African Journals Online, CINHAL, HINARI, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PubMed/Medline. Independent critical appraisal of retrieved studies was done using the Newcastle–Ottawa assessment checklist. The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA version 14 software. The I2 statistics were used to test heterogeneity, whereas publication bias was assessed by Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The results of the meta-analysis were explained in the Odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and presented using forest plots. A total of seven articles were included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis. Based on the data retrieved from the articles, 35.7% of women in Ethiopia had good knowledge about preconception care. The subgroup analysis based on region revealed the lowest (22.34%) and highest (45.06%) percentage of good knowledge on preconception care among women who were living in Amhara and Oromia regions, respectively. Moreover, women who utilized family planning services were three and more times (OR 3.65 (95% CI 2.11, 6.31)) more likely to have a good level of knowledge about preconception care. One-third of Ethiopian women had good knowledge about preconception care. Family planning utilization had a positive impact on women’s knowledge of preconception care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preconception care (PCC) is an important and preventive health care intervention for couples before conception1,2. PCC is an interventional opportunity to improve maternal outcomes and the future generation3,4. It is a strategy by which biomedical, behavioral and social health-related interventions are provided to the couples through risk screening and health education5,6,7. It also considers treatments, if indicated2. Generally, PCC is a cost-effective tool for women with chronic disease in the primary setting8.

PCC contributes to reducing maternal and childhood mortality and morbidity, globally9. Its role outweighs in pockets of socially marginalized and economically deprived families and communities8,9. It reduces potential low birth weight, abortion, prematurity, and congenital anomalies, and maternal hyperglycemia10,11,12,13. Its effective utilization also improves maternal and child health through the early initiation of antenatal care10,14. Moreover, pregnant women who received PCC were more likely to be supplemented with foliate, be vaccinated, received a better level of care for their pre-existing health condition15. Because of the above reasons, the majority of maternal and infant morbidities and mortalities are reduced through quality PCC16,17.

Although there are appropriate interventional strategies to increase the knowledge and uptake of PCC in the community18,19, the current studies revealed women’s awareness about PCC and its utilization is low20,21. The knowledge level of PCC varies significantly from across the world22,23. Studies were done on knowledge on preconception care found between 17.3%16 in Ethiopia and 71.9% in Lebanon22. Nowadays clinical interventions to be offered before conception to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes have been identified24. But, the practice and implementation of preconception care are still at their initial phase25. Due to the low level of knowledge on PCC, its utilization is also lower20,26. Likewise, the couple’s intention to seek out PCC is insufficient23. Different studies in Ethiopia showed the women’s knowledge of PCC as a basic issue for implementation of a maternal continuum of care27,28,29 However, none of them are inconclusive in determining the knowledge level and its predictors.

The national-level estimation is vital to design and apply evidence-based strategies. Especially in the less developed world where maternity care is started after the second half of pregnancy age30.

Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to know the national level knowledge of preconception care among women in Ethiopia. The review question was what is the knowledge and utilization of preconception care among pregnant women in Ethiopia?

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of all observational published studies to assess the pooled prevalence and determinants of preconception care in Ethiopia. Retrieving of the included studies was done in different databases such as Google scholar, African Journals Online, CINHAL, HINARI, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PubMed (Medline). Moreover, grey literature was considered through reviewing the lists of references. Additionally, unpublished work eligible for our meta-analysis in Addis Ababa digital library was searched. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline was strictly followed during systematic review and meta-analysis31.

A combination of search terms that best describe the study variables were used to retrieve articles. These include risk factors, determinants, predictors, factors, magnitude, prevalence, incidence, preconception care, knowledge, and Ethiopia. The terms were combined using “OR” and “AND” Boolean operators. Additionally, the reference list of the already identified articles was checked to find additional eligible articles but was missed during the initial search. The searching was carried out from June 2 to July 1, 2020.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All observational published and unpublished studies that reported knowledge of preconception care among pregnant women in Ethiopia were included.

Exclusion criteria

Clinical trials, case reports, ecological studies, and reviews were excluded. Moreover, articles that were not fully accessible were excluded after a minimum of three email contacts with the cross ponding authors.

Outcome of interest

The main outcome of interest was the prevalence of knowledgeable women on PCC in Ethiopia. The prevalence of knowledgeable women was computed based on the correct response using PCC knowledge questions32. Estimating the association between PCC knowledge and family planning usage was the second outcome of interest.

Data extraction

Three authors (AAA, LBZ & GMK) searched all records independently then extracted the data using standardized format on Microsoft Excel. The format included: first author, publication year, study design, region of study, sample size, knowledge of PCC, and study's quality. Finally, the other authors (MSB, ES, YS, YY & MD) were involved in resolving the disagreements on the quality score of each study.

Quality assessment of studies

Each record included in this meta-analysis was assessed by the two authors (AAA & GMK), intensively using the Newcastle–Ottawa assessment checklist for observational studies33. The checklist has three parts; the methodological assessment and the comparability evaluation are rated up to five and three stars respectively. Similarly, the important variables including the outcome variable were taken and used in this study. Articles scored ≥ 6 out of 10 were considered as high quality and utilized for this meta-analysis. The uncertainty between the assessors was solved with discussion considering the score by another author.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The data were exported from Microsoft Excel to STATA version 14 software34 for statistical analysis. The summarized and descriptive results were shown using figures and tables. This review was conducted to determine the knowledge and utilization of preconception care in Ethiopia. The pooled knowledge of preconception care among reproductive pregnant women was assessed considering the random-effect model. Due to the heterogeneity by study design and study regions /areas. I2 statistics of 25, 50, and 75% were used to declare low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively35. We had subgroup analysis by region because of the heterogeneity among the included studies to estimate the pooled prevalence. We have also checked publication bias using Egger’s and Begg’s tests, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare its statistical significance36,37.

Results

Study selection

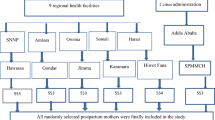

All observational studies on preconception care among women in Ethiopia were included in this systematic and meta-analysis. A total of 198 articles were found on the databases 160 of which were duplicated and removed through title screening. After a screening of all the retrieved records, 18 articles were excluded by reviewing their abstracts. A total of 20 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, finally, 7 studies were included in the meta-analysis of this study (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

A total of seven observational studies16,17,32,38,39,40,41 were included in the current systematic and meta-analysis. The studies were both institution and community-based, reported knowledge of preconception care. Of the included studies16,32, were conducted in Amhara38,39, were conducted in Oromia17,41, were conducted in SNNPR, and40 was conducted in Addis Ababa (AA). The sample size of included studies ranged from 142 in AA40 to 669 in Oromia39. A total of 2995 women participated in the current study. The included studies’ quality was between 6 and 9 (Table 1).

Knowledge of preconception care among women in Ethiopia

The women’s knowledge on PCC among the studies included in this study was ranged from 17.3% in Amhara16 to 63.4% in Oromia38. Due to the high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.4%) observed in this analysis, the random effect model was considered to estimate the pooled prevalence. Therefore, the pooled estimated knowledgeable women in Ethiopia on preconception care was 35.70% (95% CI 23.25, 48.15) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis by region was conducted due to the high heterogeneity observed. Based on this, the highest knowledgeable women on PCC were found in Oromia 45.06% (95% CI 9.19, 80.93). Whereas, the lowest knowledgeable women were found in Amhara 22.34% (95% CI 12.34, 32.33). Moreover, the Duval and filled analysis was conducted to fill the publication bias identified by Egger test with unpublished studies (Fig. 3).

The association between family planning usage and PCC knowledge

Three studies32,39,40 that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included to determine the association of pooled PCC knowledge and family planning usage among women in Ethiopia. All of the studies showed a history of family planning usage had a positive association with PCC knowledge. Due to the moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70.3%) observed in this analysis, a random effect meta-analysis model was employed to determine the association. Based on this, family planning usage had a significant association with PCC knowledge 3.65% (95% CI 2.11, 6.31), p-value = 0.034. Moreover, the absence of potential publication bias was confirmed with a p value of 0.165 and 0.296 Egger’ test and Begg’s test, respectively (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Every reproductive-aged woman should receive preconception care before she becomes pregnant42. PCC is an important means of improving women’s and infants’ health outcomes43. To have improved PCC multi-strategic interventions are required44. It needs serious attention from the government and stakeholders27. The current systematic review and meta-analysis were aimed to identify the knowledge of PCC and its association with family planning usage among women in Ethiopia.

This study disclosed the pooled knowledgeable pregnant women in Ethiopia on preconception care were 35.70% (95% CI 23.25, 48.15). This finding is consistent with the other studies conducted in Turkey (46.3%)45 and Saudi Arabia (37.9%)46. But, it is higher than the findings from studies conducted in Sudan (11.1%)47 and Iran (10.4%)48. The possible reason for the observed difference might be due to the difference in study participants and methods of assessment. The study in Sudan was conducted exclusively among reproductive-aged women with rheumatic heart disease, unlike the current study that considered all reproductive-aged women. Unlike the articles included in the current meta-analysis, the Donabedian model utilized for the study in Iran could bring the difference.

However, the magnitude of knowledgeable women in this meta-analysis is lower than the study conducted in Malaysia which showed 51.9% of women were knowledgeable about PCC49. Similarly, the finding from the current meta-analysis is lower than studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, the United States of America, and Jordan revealed that (84.6%), (76%) and (85%), respectively50,51,52. The difference in socio-demographic characteristics, sampling, and study setting of study participants, the studies considered might the possible reasons for the discrepancy observed. The study from Malaysia included educated women whereas the current meta-analysis women regardless of their educational status. It is evident education improves the skill of searching information32 and maternal awareness of her health care services53. Likewise, for the studies in Saudi Arabia and the U.S.A, a non-probability sampling method was employed to select the participant. Moreover, the studies in U.S.A and Jordan were conducted exclusively in maternal and child care clinics unlike the current meta-analysis included both institution-based and community-based studies.

The utilization of family planning among study participants in this meta-analysis is significantly associated with knowledge on PCC. Women who utilized fa2mily planning services were more likely to be knowledgeable about PCC. This finding is supported by the studies conducted in Sudan54. This might be due to family planning service is a means to improve individuals’ health condition before a planned pregnancy55. Women who postpone their pregnancy have an increased need for preconception counseling55. Therefore, the prevalent neural tube defect in Ethiopia24 can be prevented through preconception counseling during family planning service provision.

Limitations of the study

This meta-analysis has limitations. Only articles and reports in the English language were included. Additionally, all the included articles were cross-sectional study design, in which the association might be affected by confounders. Moreover, the included studies were from only two regions and one city administrative. Therefore, the findings from this meta-analysis may not be representative of the country due to the limited number of articles.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis revealed, less than two-fifth of reproductive-aged women are knowledgeable about PCC in Ethiopia. Likewise, family planning utilization has a significant association with PCC knowledge.

Data availability

Data used for this study are available from the authors of each included study upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PCC:

-

Preconception care

- AA:

-

Addis Ababa

- SNNPR:

-

South Nations Nationalities and People’s Region

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

References

Hillemeier, M. M., Weisman, C. S., Chase, G. A., Dyer, A. & Shaffer, M. L. Use of Health Services Women’s preconceptional health and use of health services: Implications for preconception care. Health Serv. Res. 43, 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00741.x (2007).

Shannon, G. D., Alberg, C., Nacul, L. & Pashayan, N. Preconception healthcare delivery at a population level: Construction of public health models of preconception care. Matern. Child Health J. 18, 1512–1531 (2014).

Care, P. et al. Diabetes during pregnancy: Surveillance, preconception care, and postpartum care. J. Womens Health 27, 1–6 (2018).

Catalao, R., Mann, S., Wilson, C. & Howard, L. M. Preconception care in mental health services: Planning for a better future. Br. J. Psychiatry 216, 180–181 (2020).

Mason, E. et al. Preconception care: Advancing from ‘important to do and can be done’ to ‘is being done and is making a difference’. Reprod. Health 11, 1–9 (2014).

Denny, L. & Anorlu, R. Cervical cancer in Africa. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 21, 1434–1438 (2012).

Perlman, S. et al. Knowledge and awareness of HPV vaccine and acceptability to vaccinate in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 9, e90912 (2014).

Mittal, P., Dandekar, A. & Hessler, D. Use of a modified reproductive life plan to improve awareness of preconception health in women with chronic disease. Perm. J. 18, 28–32 (2014).

WHO. Meeting to Develop a Global Consensus on Preconception Care to Reduce Maternal and Childhood Mortality and Morbidity 78 (WHO Headquarters, 2012).

Tieu, J., Middleton, P., Crowther, C. A. & Shepherd, E. Preconception care for diabetic women for improving maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007776.pub3 (2017).

Nagpal, J. et al. Knowledge about human papillomavirus and time to complete vaccination among vulnerable female youth. J. Pediatr. 171, 122–127 (2016).

Wing, W. et al. Uptake of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Hong Kong: Facilitators and barriers among adolescent girls and their parents. PLoS ONE 13, e0194159 (2018).

Jourabchi, Z. et al. Association between preconception care and birth outcomes. Am. J. Health Promot. 33, 363–371 (2019).

Montanaro, C., Lacey, L., Robson, L., Estill, A. & Vukovic, S. Preconception care: A technology-based model for delivery in the primary care setting supported by public health. Matern. Child Health J. 23, 1581–1586 (2019).

Hemsing, N., Greaves, L. & Poole, N. Preconception health care interventions: A scoping review. Sex. Reprod. Healthcare 14, 24–32 (2017).

Demisse, T. L. et al. Utilization of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in Debre Birhan town, North Shewa, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 16, 96 (2019).

Kassa, A. & Yohannes, Z. Women ’ s knowledge and associated factors on preconception care at Public Health Institution in Hawassa City, South Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3951-z (2018).

Skogsdal, Y., Fadl, H., Cao, Y., Karlsson, J. & Tydén, T. An intervention in contraceptive counseling increased the knowledge about fertility and awareness of preconception health—A randomized controlled trial. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 124, 203–212 (2019).

Sijpkens, M. K. et al. The effect of a preconception care outreach strategy: The healthy pregnancy 4 all study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 60 (2019).

Asresu, T. T., Hailu, D., Girmay, B. & Abrha, M. W. Mothers’ utilization and associated factors in preconception care in northern Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Preg. Childbirth 1, 1–7 (2019).

Abrha, M. W., Asresu, T. T. & Weldearegay, H. G. Husband support rises women’s awareness of preconception care in Northern Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2020, 5–7 (2020).

Tamim, H. et al. Preconceptional folic acid supplement use in Lebanon. Public Health Nutr. 12, 687–692 (2009).

Temel, S. et al. Knowledge on preconceptional folic acid supplementation and intention to seek for preconception care among men and women in an urban city: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0774-y (2015).

Atrash, H. & Jack, B. Preconception care to improve pregnancy outcomes: The science. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 30, 334–341 (2020).

Bitew, Z. W., Worku, T., Alebel, A. & Alemu, A. Magnitude and associated factors of neural tube defects in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Pediatr. Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X20939423 (2020).

Onasoga, A. O., Osaji, T. A., Alade, O. A. & Egbuniwe, M. C. Awareness and barriers to utilization of maternal health care services among reproductive women in Amassoma community, Bayelsa State. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 6, 10–15 (2014).

Woldeyes, B. S., Erena, M. M. & Demisse, G. A. Knowledge, uptake of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in West Shewa zone. BMC Women’s Health 20, 1–8 (2020).

Goshu, Y. A., Liyeh, T. M., Ayele, A. S., Zeleke, L. B. & Kassie, Y. T. Women’s awareness and associated factors on preconception folic acid supplementation in Adet, Northwestern Ethiopia, 2016: Implication of reproductive health. J. Nutr. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4936080 (2018).

Bekele, M. M., Gebeyehu, N. A., Kefale, M. M. & Bante, S. A. Knowledge of preconception care and associated factors among healthcare providers working in public health institutions in Awi Zone, North West Ethiopia, 2019: Institutional-based cross-sectional study. J. Pregn. 2020, 1–7 (2020).

Berglund, A. & Lindmark, G. Preconception health and care (PHC)—A strategy for improved maternal and child health. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 121, 216 (2016).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 8, 336–341 (2010).

Ayalew, Y., Mulat, A., Dile, M. & Simegn, A. Women’s knowledge and associated factors in preconception care in adet, west gojjam, northwest Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study. Reprod. Health 14, 15 (2017).

Modesti, P. A. et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 11, e0147601 (2016).

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software (2015).

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994).

Gezahegn, A. Assessment knowledge and experience of preconception care among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care in West Shoa Zone Public Health Centers, 2016 (2016).

Fekene, D. B., Woldeyes, B. S., Erena, M. M. & Demisse, G. A. Knowledge, uptake of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in West Shewa zone, Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Womens. Health 20, 1–8 (2020).

Kassie, A. Assessment of knowledge and experience of preconception care and associated factors among pregnant mothers with pre existing diabetes mellitus attending diabetic follow up clinic at selected governmental hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. (2018).

Yohannes, Z. et al. Levels and correlates of knowledge and attitude on preconception care at public hospitals in Wolayita Zone, South Ethiopia. BioRxiv 586636 (2019).

Kasim, R., Draman, N. & Kadir, A. A. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of preconception care among women attending appointments at a rural clinic in Kelantan. Educ. Med. J. 8, 57–68 (2016).

Floyd, R. L. et al. A national action plan for promoting preconception health and health care in the United States (2012–2014). J. Women’s Health 22, 797–802 (2013).

Johnson, K. et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and Health Care—United States: Report of the CDC/ATSDR preconception care work group and the select panel on preconception care. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. 55, 1 (2006).

Baykan, Z., Öztürk, A., Poyrazoğlu, S. & Gün, İ. Awareness, knowledge, and use of folic acid among women: A study from Turkey. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 283, 1249–1253 (2011).

Madanat, A. Y. & Sheshah, E. A. Preconception care in Saudi women with diabetes mellitus. J. Family Community Med. 23, 109 (2016).

Ahmed, K., Saeed, A. & Alawad, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of preconception care among Sudanese women in reproductive age about rheumatic heart disease. Int. J. Public Health 3, 223–227 (2015).

Ghaffari, F., Jahani Shourab, N., Jafarnejad, F. & Esmaily, H. Application of Donabedian quality-of-care framework to assess the outcomes of preconception care in urban health centers, Mashhad, Iran in 2012. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 2, 50–59 (2014).

Kasim, R., Draman, N., Kadir, A. A. & Muhamad, R. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of preconception care among women attending maternal health clinic in Kelantan. Educ. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.5959/eimj.v8i4.475 (2016).

Gautan, P. & Dhakal, R. Knowledge on preconception care among reproductive age women. Saudi J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2, 6 (2016).

Coonrod, D. V., Bruce, N. C., Malcolm, T. D., Drachman, D. & Frey, K. A. Knowledge and attitudes regarding preconception care in a predominantly low-income Mexican American population. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200, 686 (2009).

Al-Akour, N. A., Sou’Ub, R., Mohammad, K. & Zayed, F. Awareness of preconception care among women and men: A study from Jordan. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. (Lahore) 35, 246–250 (2015).

Bado, A. R. & Susuman, A. S. Women’s education and health inequalities in under-five mortality in selected sub-saharan African countries, 1990–2015. PLoS ONE 11, 1–18 (2016).

Yassin, K. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of preconception care among Sudanese women in reproductive age about rheumatic heart disease at Alshaab and Ahmad Gassim hospitals 2014–2015 in Sudan. Basic Res. J. Med. Clin. Sci. 4, 199–203 (2015).

Kallner, H. K. & Danielsson, K. G. Prevention of unintended pregnancy and use of contraception—Important factors for preconception care. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 121, 252 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the authors of the articles included in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A., E.S.G. and L.B.Z. involved in the conception of the study protocol, the design, selection of articles, data extraction, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing of this review whereas M.S.B., M.D., Y.S., Y.Y. and G.M.K. were involved in the selection of articles, data extraction, and reviewing and editing the final manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alemu, A.A., Bitew, M.S., Zeleke, L.B. et al. Knowledge of preconception care and its association with family planning utilization among women in Ethiopia: meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 10909 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89819-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89819-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.