Abstract

Despite randomized trials showing a functional outcome benefit in favor of endovascular therapy (EVT), large artery occlusion acute ischemic stroke is associated with high mortality. We performed a retrospective analysis from a prospectively collected code stroke registry and included patients presenting between November 2016 and April 2019 with internal carotid artery and/or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusions. Ninety-day mortality status from registry follow-up was corroborated with the Social Security Death Index. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to determine demographic and clinical characteristics associated with 90-day mortality. Among 764 patients, mortality rate was 26%. Increasing age (per 10 years, OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.25–1.76; p < 0.0001), higher presenting NIHSS (per 1 point, OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09, p = 0.01), and higher discharge modified Rankin Score (per 1 point, OR 4.27, 95% CI 3.25–5.59, p < 0.0001) were independently associated with higher odds of mortality. Good revascularization therapy, compared to no EVT, was independently associated with a survival benefit (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.35–1.00, p = 0.048). We identified factors independently associated with mortality in a highly lethal form of stroke which can be used in clinical decision-making, prognostication, and in planning future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endovascular therapy (EVT) improves functional outcome in selected patients with anterior circulation, large artery occlusion (LAO) acute ischemic stroke (AIS)1,2,3. Randomized trials have demonstrated the benefit of EVT in patients treated within 6 h of Last Known Well (LKW) time1. In later time windows, EVT also benefits patients with evidence of salvageable brain tissue on advanced imaging, or a mismatch between clinical exam findings and the volume of infarcted brain tissue2,3.

Despite this, LAO AIS remains associated with high mortality. In a meta-analysis of randomized trials demonstrating the benefit of EVT within 6 h, mortality rates in the thrombectomy and standard medical therapy arms were 15% and 19%, respectively1. The Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke (DEFUSE 3) trial, which enrolled patients between 6 and 16 h with evidence of salvageable brain tissue, reported mortality rates in the thrombectomy and medical therapy arms of 14% and 26%, respectively2. Lastly, the DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo (DAWN) trial, which enrolled patients between 6 and 24 h with a mismatch between exam and imaging findings, showed respective mortality rates of 19% and 18% in the thrombectomy and standard medical therapy groups3.

We investigated demographic and clinical characteristics associated with mortality in patients presenting with proximal, anterior circulation LAO AIS. Identifying predictors of mortality in this highly lethal form of stroke has the potential to assist in therapeutic decision-making, prognostication, and for future studies.

Methods

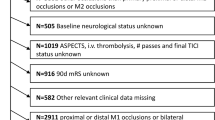

From November 2016 to April 2019, we conducted a retrospective analysis from a large healthcare system’s prospectively collected code stroke registry of patients with internal carotid artery (ICA) and/or proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA), M1 or M2 occlusions. Ninety-day mortality status from registry follow-up was corroborated with the Social Security Death Index.

Subjects were required to present within 24 h of LKW time. Patients were selected for EVT based on the local guideline for the healthcare system, which closely mirrors recommendations from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association4 (Table 1). Post-thrombectomy reperfusion was determined by neuro-interventionalist calculated Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) scores. Patients were not required to have been treated with EVT for study inclusion.

All patient characteristics were de-identified. Study approval was obtained from the Atrium Health, Carolinas Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB, File #07–19-21E). Carolinas Medical Center is a certified Comprehensive Stroke Center. Due to the study design and use of de-identified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic and clinical characteristics. Baseline clinical characteristics included comorbidities, presenting glucose level, time from LKW to Computed Tomography (CT) imaging, CT image completion, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), modified Rankin Scale (mRS), thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score (good defined as 2b-3), type of treatment (no EVT, EVT only, or IV alteplase and EVT), and revascularization therapy (interaction term for treatment type and baseline TICI score good/poor). Ninety-day mortality was calculated from admission date and confirmed using the Social Security Death Index Masterfile. Univariate analysis was performed to examine risk factors associated with 90-day mortality. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to determine demographic and clinical characteristics associated with 90-day mortality. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 2. In 764 total subjects, mean age was 68 years, 52% were women, and mean NIHSS was 14. Fourteen percent of patients presented with an ICA occlusion, 76% with an MCA occlusion, and 10% had tandem ICA and MCA occlusions.

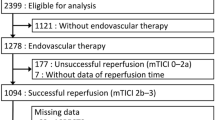

Seventy-two percent of patients presented in the 0–6 h time window, while approximately 28% presented in the 6–24 h time window. Nearly 40% were treated with IV alteplase. Twenty-five percent were treated with IV alteplase and EVT, and 26% received EVT only.

Mortality rate for the entire cohort was 26% (Table 3). Substantial differences between the survival and mortality groups were seen with respect to age, gender, race, presenting glucose, presence of ICA occlusion, presenting NIHSS, history of hypertension, history of atrial fibrillation, CT perfusion (CTP) core infarction volume (cerebral blood flow, CBF < 30%, IschemaView RAPID), CTP delayed perfusion volume (Time to maximum greater than 6 s, Tmax > 6 s, IschemaView RAPID), treatment with EVT, revascularization therapy, and discharge mRS (Table 3).

In the multivariable model (Table 4), increasing age (per 10 years, OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.25–1.76; p < 0.0001), higher presenting NIHSS (per 1 point, OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09, p = 0.01), and higher discharge mRS (per 1 point, OR 4.27, 95% CI 3.25–5.59, p < 0.0001) were associated with higher odds of mortality. Good revascularization therapy (TICI 2b-3), compared to no EVT, was associated with a survival benefit at 3 months (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.35–1.00, p = 0.048).

Discussion

Our retrospective analysis from prospectively collected data on 764 subjects showed an independent association between age, NIHSS, and discharge mRS with 90-day mortality in patients with ICA and/or proximal MCA occlusions. Good revascularization therapy, compared to no EVT, improved 90-day survival.

Numbers-needed to treat for functional independence in the Highly Effective Reperfusion evaluated in Multiple Endovascular Stroke (HERMES) trial, DEFUSE 3, and DAWN cohorts were 2.6, 2, and 2.8, respectively1,2,3. While a meta-analysis suggests that EVT improves 3-month survival compared to best medical therapy5, EVT has demonstrated a statistically significant mortality benefit in only a single randomized trial6. Identifying subsets of patients at higher risk of death is thus especially important, as this can guide clinical management, assist family discussions and prognostication, and help plan future clinical trials. Modifiable risk factors may be targeted in future studies, additional relevant clinical endpoints for studies can be elucidated, and evidence-based therapies for improvement in functional outcome, such as EVT, may be refined in order to reduce mortality risk.

Other groups have identified factors associated with mortality at various time points after stroke, including in-hospital models and 1-year predictive models7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, exclusive to LAO patients, these models have been specifically designed and/or validated to predict either good or poor functional outcome17,18,19,20,21,22. Our work is unique in targeting LAO patients that have been treated with best medical therapy + /− EVT, with the dependent variable of mortality at 90 days, rather than poor outcome (often defined as mRS 4–6).

Among the common mortality associations in other studies include age7,8,9,10,14,16, initial stroke severity7,8,9,13,14,15,16 presenting glucose8,16, pre-morbid function7,8,9, and history of atrial fibrillation8,9,10,15. We similarly found that age, initial stroke severity, presenting glucose, and history of atrial fibrillation were significant univariate associations with mortality risk, though among these factors, the multivariable model demonstrated independent mortality associations with increasing age, presenting NIHSS, and discharge mRS. These differences may be explained by the heterogeneity of the patient cohorts and treatment algorithms.

While age17,18,19,20,21,22 and stroke severity17,18,19,20,21 have previously been incorporated into functional outcome prediction models for LAO patients, as well as into prognostic models for non-selected ischemic stroke patients7,8,9,10,15, our findings of an independent association with mortality in strictly the LAO population is novel. In addition, to our knowledge, discharge functional outcome has not previously been demonstrated to predict mortality, though we have recently shown its importance in predicting 90-day outcome in basilar artery occlusion patients treated with EVT23.

Moreover, while good revascularization may improve survival in the thrombectomy population24,25,26, our study demonstrated that TICI 2b-3 revascularization, compared to no EVT, produced a survival benefit. This may seem intuitive, as patients receiving no EVT may be categorized into the “no revascularization” or “poor revascularization” group of a thrombectomy-only study. However, we believe this is still significant in that this was shown in a cohort of patients that included exclusively medically managed LAO patients, indicating that the treatment effect of only medical therapy did not modify this benefit. Future studies may build on our findings to develop mortality prediction models specifically in this subset of patients, as other groups have done for functional outcome17,18,19,20,21,22.

The logistic regression model showed that each increasing decade of life elevated odds of 90-day mortality by nearly 1.5 times. While age is a non-modifiable risk factor, quantification of its contribution to mortality risk is helpful during hospital management and prognostication. It should be emphasized that thrombectomy should still be offered to older patients, as the clinical benefit in favor of treatment for functional improvement has been demonstrated across the spectrum of age ranges in randomized trials1,2,3. Subgroup analyses from early and late-window thrombectomy trials demonstrate a trend for higher likelihood of functional independence in older patients than younger patients treated with EVT, compared to similar age patients treated with best medical therapy1,2,3. Further studies may focus specifically on the impact of age on risk of mortality in this population.

One might also hypothesize that discharge mRS impacts risk of 90-day mortality. In our study, an over fourfold odds of death were found with each increasing point on the mRS at discharge. Discharge mRS may be impacted by multiple factors, including pre-morbid mRS, presenting NIHSS, treatment with EVT, and medical co-morbidities, all of which were investigated in our study. Another factor that may influence discharge mRS is the institution of early rehabilitation. Trials conducted thus far instituting very early rehabilitation after stroke have shown mixed results, though initiation of rehabilitation within 2 weeks appears to be beneficial27. Targeting specific therapies with more defined time windows may be a focus of future studies impacting post-stroke mortality.

Elevated presenting NIHSS was associated with increased mortality risk in our study, and while presenting NIHSS may not be able to be specifically impacted, it can be used in risk assessments for prognosis. In addition, targeting primary and secondary prevention may reduce not only risk of incident stroke, but may impact collateral blood flow status28, and thereby presenting stroke severity. This specific clinical question requires additional study.

Good reperfusion, defined as achieving TICI 2b-3, has been associated with improved functional outcome after LAO stroke29,30 and may improve survival in the subset of LAO patients that are treated with EVT24,25,26. Our study demonstrated that compared to no EVT, good revascularization improved odds of survival. This further emphasizes the importance of achieving good reperfusion with EVT, and is an example of reinforcing an existing, evidence-based treatment for functional improvement for a potential survival benefit. TICI 2b-3 revascularization was achieved in 86% of patients receiving EVT in our study, and in 76% and 84% of patients in DEFUSE 3 and DAWN, respectively2, 3. In HERMES, TICI 2b-3 revascularization was achieved in a low of 59% of patients in MR CLEAN31 up to a high of 88% of subjects in SWIFT-PRIME32.

The mortality rate for our entire cohort was 26%, higher than that reported in the medical and EVT arms of prior thrombectomy trials1,2,3,5. However, elevated in-hospital mortality has been reported for EVT patients treated outside of clinical trials33. In addition, subjects who met inclusion criteria for DEFUSE 3 and DAWN were required to have a mismatch between infarcted brain tissue and salvageable brain tissue, or a mismatch between infarcted tissue and clinical exam findings. As such, most patients in DEFUSE 3 or DAWN likely had “slow-growing” infarcts by meeting inclusion criteria for the trials. Accordingly, subjects randomized to the medical therapy arms of the trials might be expected to have better outcomes than subjects who did not meet trial criteria. An extension of this so-called “late-window paradox”34 for good outcome may also apply to mortality, such that meeting trial enrollment criteria may offer a protective survival benefit. In our study, late window (6–24 h) patients comprised 28% of all subjects and just over 50% of all subjects were treated with EVT.

Moreover, the elevated number of M2 branch occlusions in our study (over 30% of total subjects, compared to 8 total patients in DEFUSE 3 and DAWN and 8% in HERMES), higher ischemic core volume (mean of 27 cc, compared to 10 cc in DEFUSE 3 and 8 cc in DAWN), and inclusion of subjects with mRS 0–2 (rather than 0–1) for EVT may have contributed to our higher mortality as well.

Our study had several limitations. Pre-morbid mRS scores were not consistently available and could not be analyzed, though discharge mRS scores were captured. While obtained in over three-quarters of patients, CTP was not routinely performed on every LAO patient, limiting the conclusions that may be drawn from these data. The focus of our study was on mortality, though some might consider an mRS score of 5 to be an equally bad or worse outcome than death. The sub-category of patients with mRS 5 was not quantified at 3 months, as outcome data on patients not treated with alteplase or EVT was not routinely captured at 90 days. Some patients died as a direct result of stroke, while others died after withdrawal of care when meaningful neurological recovery appeared exceedingly unlikely. Patients who died as a result of withdrawal of care were not independently analyzed.

Conclusion

Increasing age, higher presenting NIHSS, and worse discharge functional outcome were associated with 90-day mortality after LAO AIS in our study. Good revascularization after EVT, compared to no EVT, improved survival. These factors may be used in clinical settings to assist in treatment, prognostication, resource allocation, financial planning, and in future trials.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goyal, M. et al. HERMES collaborators. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 387, 1723–1731 (2016).

Albers, G. W. et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 708–718 (2018).

Nogueira, R. G. et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 11–21 (2018).

Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke STR0000000000000211 (2019).

Katsanos, A. H. et al. Mortality risk in acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion treated with mechanical thrombectomy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e014425 (2019).

Goyal, M. et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1019–1030 (2015).

Gattringer, T. et al. Predicting early mortality of acute ischemic stroke: score-based approach. Stroke 50, 349–356 (2019).

Saposnik, G. et al. IScore: a risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation 123, 739–749 (2011).

O’Donnell, M. J. et al. The PLAN score: a bedside prediction rule for death and severe disability following acute ischemic stroke. Arch. Intern. Med. 172, 1548–1556 (2012).

Smith, E. E., Shobha, N., Dai, D., Olson, D. W. M. & Reeves, M. J. Risk score for in-hospital ischemic stroke mortality derived and validated within the Get With the Guidelines–Stroke Program. Circulation 122, 1496–1504 (2010).

Wang, Y., Lim, L.L.-Y., Heller, R. F., Fisher, J. & Levi, C. R. A prediction model of 1-year mortality for acute ischemic stroke patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 84, 1006–1011 (2003).

Koennecke, H.-C. et al. Factors influencing in-hospital mortality and morbidity in patients treated on a stroke unit. Neurology 77, 965–972 (2011).

Bustamante, A. et al. The impact of post-stroke complications on in-hospital mortality depends on stroke severity. Eur. Stroke J. 2, 54–63 (2017).

Solberg, O. G., Dahl, M., Mowinckel, P. & Stavem, K. Derivation and validation of a simple risk score for predicting 1-year mortality in stroke. J. Neurol. 254, 1376–1383 (2007).

Heuschmann, P. U. et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and attributable risks of death after ischemic stroke: the German Stroke Registers Study Group. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1761–1768 (2004).

Ben Hassen, W. et al. MT-DRAGON score for outcome prediction in acute ischemic stroke treated by mechanical thrombectomy within 8 hours. J. Neurointerv. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015105 (2019).

Hallevi, H. et al. Identifying patients at high risk for poor outcome after intra-arterial therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 40, 1780–1785 (2009).

Sarraj, A. et al. Optimizing prediction scores for poor outcome after intra-arterial therapy in anterior circulation acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 44, 3324–3330 (2013).

Saposnik, G., Guzik, A. K., Reeves, M., Ovbiagele, B. & Johnston, S. C. Stroke prognostication using age and NIH stroke scale: SPAN-100. Neurology 80, 21–28 (2013).

Flint, A. C., Cullen, S. P., Faigeles, B. S. & Rao, V. A. Predicting long-term outcome after endovascular stroke treatment: the totaled health risks in vascular events score. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 31, 1192–1196 (2010).

Rangaraju, S. et al. Pittsburgh Response to Endovascular therapy (PRE) score: optimizing patient selection for endovascular therapy for large vessel occlusion strokes. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 7, 783–788 (2015).

Liggins, J. T. P. et al. A score based on age and DWI volume predicts poor outcome following endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Int. J. Stroke 10, 705–709 (2015).

Karamchandani, R. R. et al. Age and discharge modified Rankin score are associated with 90-Day functional outcome after basilar artery occlusion treated with endovascular therapy. Interv. Neuroradiol. 1591019920987040 (2021).

Nogueira, R. G., Liebeskind, D. S., Sung, G., Duckwiler, G. & Smith, W. S. Predictors of good clinical outcomes, mortality, and successful revascularization in patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing thrombectomy: pooled analysis of the Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia (MERCI) and Multi MERCI Trials. Stroke 40, 3777–3783 (2009).

Fields, J. D., Lutsep, H. L. & Smith, W. S. Higher degrees of recanalization after mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke are associated with improved outcome and decreased mortality: pooled analysis of the MERCI and multi MERCI trials. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 32, 2170–2174 (2011).

Awad, A.-W. et al. Predicting death after thrombectomy in the treatment of acute stroke. Front. Surg. 7, 16 (2020).

Coleman, E. R. et al. Early rehabilitation after stroke: a narrative review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 19, 59 (2017).

Menon, B. K. et al. Leptomeningeal collaterals are associated with modifiable metabolic risk factors. Ann. Neurol. 74, 241–248 (2013).

Yoo, A. J. et al. Refining angiographic biomarkers of revascularization. Stroke 44, 2509–2512 (2013).

Marks, M. P. et al. Angiographic outcome of endovascular stroke therapy correlated with MR findings, infarct growth, and clinical outcome in the DEFUSE 2 trial. Int. J. Stroke 9, 860–865 (2014).

Berkhemer, O. A. et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 11–20 (2015).

Saver, J. L. et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs t-PA alone in stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2285–2295 (2015).

Qureshi, A. I. et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke patients performed within and outside clinical trials in the United States. Neurosurgery 86, E2–E8 (2020).

Albers, G. W. Late window paradox. Stroke 49, 768–771 (2018).

Funding

This research received no specific Grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: R.R.K., J.B.R., D.S., A.W.A.; Methodology: R.R.K., J.B.R., D.S.; Data curation: D.S., J.B.R.; Formal analysis: D.S., B.C.; Writing—original draft: R.R.K.; Writing—review and editing: R.R.K., J.B.R., D.S., B.C., A.W.A.; Supervision: A.W.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karamchandani, R.R., Rhoten, J.B., Strong, D. et al. Mortality after large artery occlusion acute ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 11, 10033 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89638-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89638-x

This article is cited by

-

Neurovascular and infectious disease phenotype of acute stroke patients with and without COVID-19

Neurological Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.