Abstract

Multimorbidity is more than just the addition of individual illnesses, and its diagnosis and treatment poses special problems. General practitioners play an important role in looking after multimorbid patients. The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence and pattern of acute and chronic multimorbidity in primary care patients, regardless of body system and age group. A convenience sample of 2099 patients treated by 40 general practitioners was assessed using the Burvill scale. This measure of multimorbidity differentiates according to organ system and covers both acute and chronic illnesses. It also allows severity ratings to be assessed for both acute and chronic conditions, and thus patients’ actual need for general practice care. Patients reported an average of 3.5 (SD = 2.0) acute and/or chronically affected body systems. Overall, 12.7% of patients reported only one health problem, 83.0% at least two, 65.8% at least three, 46.1% at least four, and 29.7% five or more. The most frequent problems were musculoskeletal (62.5%) and psychological (56.6%). Some morbidities were interrelated, while others co-occurred despite being medically independent. In primary care, multimorbidity is the rule rather than the exception. Acute and chronic morbidity both contribute to the burden of illness. Body systems reflect treatment needs. Instead of specialist treatment for individual illnesses, an integrative treatment approach is needed. This is the specialty of general practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary care is responsible for the treatment of 40,000 to 60,000 different illnesses and health problems. In view of this high number and the prevalence rates of illnesses, many patients inevitably suffer from several disorders simultaneously. Such multimorbidity is a serious problem in modern and aging societies in which chronic illnesses are common1,2,3,4,5,6. Multiple health problems and their treatments can interfere with each other, leading to compounding negative effects7. Multimorbid patients are also high utilizers of medical care8.

The term “multimorbidity” means that several illnesses exist concurrently. These may or may not interact with each other. In the case of a “comorbidity”, the focus is on a specific illness, the treatment of which may be complicated by additional health problems. There is no final scientific consensus on how to measure or assess multimorbidity8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Physicians treating multimorbid patients face the problem of how many medical disciplines to take into account, who should conduct the assessments, how intensively patients should be examined, whether self- or expert assessments should be used, which laboratory tests should be performed, whether only the courses of illnesses (e.g. diabetes) or also their consequences (e.g. diabetic gangrene) should be taken into account, whether medically relevant problems (carcinoma) or also those with a subjective burden (warts) should be considered, whether health care utilizers or epidemiological samples should be described, whether acute or also chronic conditions should be included, and, last but not least, what thresholds (e.g. for initiating treatment for hypertension) should be used16. A comparatively simple method to describe treatment needs and to gain clinically meaningful information on the overall health status of a person is to ask which of his or her body systems have been affected. The Burvill scale17, which identifies acute and chronic illnesses and their severity, can be used for this purpose.

The aim of this study is to collect data on the role of multimorbidity in general practice for all body systems and age groups.

Methods

Setting

Practitioners in Berlin/Brandenburg, Germany, were contacted by phone and asked whether they would participate in the study. By this means, we obtained a convenience sample of 40 practitioners that, although not epidemiologically representative for all general practitioners in the area, were “prototypically representative”18, i.e. they represented practitioners that run well-functioning practices, are well established in their jobs, and are interested in the further development of their discipline. They had all undergone specialist training as general practitioners lasting at least 5 years before they were permitted to set up in private practice. The average age of the physicians was 52.3 years (SD = 7.5, range 38–71), and 59.0% were female. They had worked in their practices for an average of 12.6 (SD = 6.2) years and had treated an average of 1115 patients (range 350–2300) in the previous three months.

The German health care system does not foresee gatekeeping, and patients can directly contact any specialist in private practice, who will then be reimbursed by the patient’s health insurer19. For this reason, the present data are especially interesting, as they only refer to patients that intentionally sought health care from their general practitioner, and not to patients in the population as a whole.

Research assistants approached all patients in the waiting rooms of the participating general practitioners, and asked them to fill in several screening surveys. As a result of this methodology, patients that consult their practitioner on a regular basis—as opposed to those who only seek treatment when they have a particular problem—are over-represented18,20.

Measure

Patients were given the Burvill survey. The survey lists ten body regions and gives short additional explanations for each of them17: (1) Cardiovascular system: e.g. hypertension, cardiac insufficiency, heart attack, arteriosclerosis, blood flow disorder or venous problems. (2) Endocrine system: e.g. thyroid dysfunction, diabetes, menopausal problems or liver diseases. (3) Respiratory system: e.g. allergic reactions, asthma, chronic bronchitis or sinusitis. (4) Genitourinary system: e.g. prostate problems, problems urinating, or insufficiency of the pelvic base. (5) Gastrointestinal tract: e.g. burping, gastric pain, intestinal illness, diarrhea, constipation or intestinal cancer. (6) Hematological/blood system: e.g. anemia, coagulopathy or special blood cells. (7) Ear and Eye: e.g. problems hearing, seeing, or conjunctivitis. (8) Musculoskeletal system: e.g. back pain, discus prolapse, pain in joints and muscles, bone fractures, rheumatism or arthrosis. (9) Nervous or neurological system: e.g. paralysis, stroke, brain tumor, multiple sclerosis or polyneuropathy. (10) Mental and psychological problems: e.g. depression, anxiety, petulance, fatigue or schizophrenia.

Patients were asked to rate acute and chronic problems for each named body system. Chronic problems were defined as having lasted longer than six months, and severity was rated on a four-point Likert scale from “(0) no illness “ to “(3) severe illness”. Patients were also asked for information on their age and gender. Such self-assessments represent what patients experience as health problems and what they are treated for. The information thus provides the clinical perspective of care, and does not reflect what the results of a comprehensive interdisciplinary medical examination would have been.

Analysis

First, the proportion of participants reporting an illness was separately calculated for each body region and according to whether the problem was acute or chronic. To shed light on different multimorbidity patterns, co-occurrences were then analyzed. Besides this descriptive approach, we also used exploratory graph analysis (EGA) to further explore the co-occurrences of medical issues in different body regions21. EGA is based on a network model (a Gaussian graphical model) and models covariance and correlations between variables. In our case, patients’ ratings for each body region (acute and chronic) are treated as the nodes, and edges in the network represent partial correlations between them. Using the R package EGAnet22, we conducted EGA, whereby we selected the regularization parameter based on the EBIC (model arguments: gamma = 0.5, lambda.min.ratio = 0.01, refit = TRUE) and conducted bootstrapping (500 iterations) to stabilize the solution.

All physicians and patients gave their informed consent in writing. There were no subjects with a guardian or below the age of 18. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. There were no experimental protocols.

The study protocol was reviewed for the fulfillment of ethical, data security, and legal requirements by the internal scientific review board of the Federal German Pension Agency and was also revised and approved by the ethical committee of the Charité University Medicine Berlin (EA4/097/09).

Results

A total of 2987 patients were approached in the waiting rooms, of whom 888 patients declined to participate in the study, and the remaining 2099 were included. The participants were between 18 and 89 years old (MW = 46.4, SD = 16.1), and 62.6% of them were female. The mean age of the females was 46.7 (SD = 16.0) and the mean age of the males 45.8 (SD = 16.3) years.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients with acute and chronic illnesses per body system. Overall, 4.2% of patients reported no illness, reflecting that GPs are not only contacted because of existing illnesses but because health certificates etc. are required. The most frequent problems were musculoskeletal (62.5%), psychological (56.6%), or with eyes/ears (46.8%). The least frequent were neurological (8.1%), blood (11.1%), and urogenital problems (17.9%).

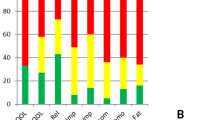

Figure 2 shows the severity ratings for acute and chronic problems per body system. About half the problems were rated mild, and ten to twenty percent severe. The most severe ratings were given to musculoskeletal, neurological and psychological problems. There is no pronounced difference between the prevalence of acute and chronic problems.

On average, patients reported acute health problems in 2.4 (SD = 2.0) and chronic health problems in 2.8 (SD = 2.1) body systems, as well as an overall 3.5 (SD = 2.0) acutely/chronically affected body systems out of the 10 presented in the instrument. Of the patients, 12.7% had only one health problem, 83.0% at least two, 65.8% at least three, 46.1% at least four, 29.7% at least five, and 16.9% six or more (Fig. 3).

There is a difference in multimorbidity prevalence between age groups. Patients under the age of 30 had on average 1.86 (SD 1.54) acute, 1.75 (SD = 1.57) chronic and 2.59 (SD = 1.67) acute/chronic problems, with 30.3% reporting none, or only one health problem. Patients between 31 and 60 years of age had an average of 2.42 (SD = 1.92) acute, 2.87 (SD = 2.12) chronic and 3.64 (SD = 2.04) acute/chronic problems, with 15.1% having none, or only one problem. Patients aged 60 or older had an average of 5.50 (SD = 2.11) acute, 3.04 (SD = 2.23) chronic and 4.12 (SD = 2.03) acute/chronic problems, with 8.5% saying they had only one problem. Nevertheless, there is even a considerable number of younger persons with more than 3 simultaneously affected body systems (< = 30 years: 27.5%, 31–60 years: 48.7%, 60 + years: 57.7%).

Females had on average 2.54 (SD = 2.00) acute, 2.94 (SD = 2.14) chronic, and 3.71 (SD = 2.04) acute/chronic problems, with 14.5% reporting none, or only one problem, and 51.2% more than three. Males reported an average of 2.25 (SD = 1.88) acute, 2.49 (SD = 2.01) chronic, and 3.20 (SD = 1.99) acute/chronic problems, with 20.9% reporting none, or only one problem, and 37.8% more than three. Taken as a whole, females reported more health problems than males in terms of overall morbidity (acute/chronic: Chi2 26.21, p < 0.001, chronic: Chi2 39.71, p < 0.001, acute: Chi2 12.99, p = 0.011).

Table 1 gives an overview on the pattern of comorbidity. For example, 74.0% of patients with an acute cardiac problem also had a chronic cardiac problem, while 34.1% also had an acute and 78.7% a chronic endocrine problem, 41.1% an acute and 38.9% a chronic pulmonary problem etc. Comorbidity rates above 70% were found for acute cardiac and chronic cardiac problems (74.0%), and for chronic endocrine problems (78.7%). Acute endocrine problems were comorbid with chronic endocrine problems (74.8%), chronic urogenital problems with chronic musculoskeletal problems (76.4%), and acute blood problems with chronic blood (74.5%) and acute musculoskeletal problems (70.7%). Acute musculoskeletal problems were comorbid with chronic musculoskeletal problems (71.0%). Acute neurological problems were comorbid with acute musculoskeletal problems (73.7%), with chronic neurological problems (77.2%), and with acute (70.2%) and chronic psychological problems (71.9%). Chronic neurological problems were comorbid with chronic musculoskeletal problems (75.5%) and chronic psychological problems (78.3%). Acute psychological problems were comorbid with chronic psychological problems (72.3%), and chronic psychological problems with acute psychological problems (80.0%). The smallest comorbidity rates were found for the comorbidity of pulmonary problems with neurobiological problems (5.9% to 8.8%) and of psychological problems with neurological problems (7.9% to 12.3%).

EGA indicates that the most strongly related comorbidities were between acute and chronic health issues in the same body region (thickness of lines in Fig. 4). Furthermore, analysis suggests that the co-occurrence of health issues in specific body regions are strongest in five clusters. Strong associations exist between the cardiovascular and endocrine systems (Fig. 4.: cluster #4), urogenital and gastrointestinal systems (cluster #3), and musculoskeletal, hearing/seeing and psychological systems (cluster #2). The respiratory system formed its own cluster (cluster #5) and did not show particularly strong links to other body regions.

Co-occurrence and clusters (1–5) of acute and chronic health problems in the ten body regions under investigation (_a = acute, _c = chronic, Car = cardiac, End = endocrine, Pul = pulmonary, Uro = urogenital, Int = gastrointestinal, Blo = blood, Eye = eye/ear, Mus = musculoskeletal, Neu = neurological, Psy = mental/psychological).

Discussion

As discussed above, conceptual and practical problems are involved in defining and measuring multimorbidity. We used the Burvill scale17, a measure of multimorbidity that (a) is organized according to organ system and is a clinically valid framework, (b) includes both acute and chronic illnesses, in contrast to most of the literature, which focuses only on chronic illnesses and thus fails to represent the actual care needs of people consulting a general practitioner, (c) rates severity for both acute and chronic conditions, and (d) represents the actual care needs of patients consulting a general practitioner and reflects the reality of this medical discipline.

The results of our study confirm those of other studies showing the high prevalence of multimorbidity in general practice patients. On average, patients have health problems in 3.5 body systems, while only 12.7% have only one problem, and 83.0% complain about issues affecting at least two body systems. Almost every second patient has four or more problems at the same time. Patients with only one illness are the exception. Our rates are higher than those reported in other studies (34% to 61% of multimorbid patients), official statistics and reimbursement systems2,8,13. However, our rates include mild health problems in addition to acute and chronic illnesses, which is important, as combinations of mild and chronic, and mild and acute disorders, can create problems of their own.

As is to be expected, the prevalence of multimorbidity is higher in the elderly and in female patients2,16, but young patients with multimorbidity also exist.

Musculoskeletal and psychological disorders are most often reported. Both frequently occur in the general population and therefore in general practice. Family physicians therefore need a thorough education in these two areas. The awareness of some illnesses with mild symptoms and little impairment (e. g. hypertension) is often low, and may therefore be underrepresented in this study. This may be the reason that only 32.4% of GP patients reported having chronic cardiovascular disease.

The comorbidity patterns shown in Table 1 reveal that some patients have health problems in as many as ten body systems (0.4%). In ten body systems, it is possible to have one of 1,233,311 different disorder combinations. The interrelations shown in Table 1 and similarly in the EG, which considers only “unique” bivariate association structures while controlling for other covariates (body regions), show highly plausible patterns. Persons who have a chronic illness in a specific body system are more likely to have acute conditions in the same system than those with no chronic conditions. Similarly, the relations between different body systems are well understood, and it is well known that musculoskeletal and psychological complaints often occur together, as do endocrinological and cardiac problems. The reported clustering of body regions may be helpful in the future investigation of common comorbidities.

Conclusion

Multimorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in primary care patients, and the problem is becoming more serious as society ages1,2,16. The predominant problems are musculoskeletal and psychological, and they are associated with much subjective suffering for the patient. General practitioners must therefore master the full range of medical specializations. As the possibilities are so numerous, controlled clinical trials and treatment guidelines will never be available for all possible combinations of multimorbidity, and most medical guidelines and educational programs focus on individual illnesses, so their validity is limited in general practice9,15,23. As multiple health problems require different medical approaches than individual illnesses, general practice is a medical specialty in its own right. The high rate of occurrence of chronic conditions should also be taken into account in the organization of care, and supports the view that general practice is perhaps the most important discipline in overall healthcare24,25.

Limitations

The sample of general practitioners is not representative of all general practitioners in all countries, and results may vary depending on the health care system and population under investigation. Our results are based on the self-reports of patients. If specialists had carried out a thorough medical assessment of the patients, the results may have been different.

References

Tiemann, M. & Mohokum, M. Demografischer Wandel, Krankheitspanorama, Multimorbidität und Mortalität in Deutschland. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung 3–11 (Springer, 2021).

Barnett, K. et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 380, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 (2012).

Cassell, A. et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 86, e245–e251. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X695465 (2018).

Koch-Institut, R. (ed.) Gesundheit in Deutschland. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Gemeinsam getragen von RKI und Destatis (RKI, 2015).

Van den Bussche, H. et al. Which chronic diseases and disease patterns are specific for multimorbidity in the elderly? Results of a claims data based cross-sectional study in Germany. BMC Public Health 11, 101 (2011).

Günnewig, T. Multimorbidität. Neurogeriatrie 23–35 (Springer, 2019).

Smith, S. M., Wallace, E., O’Dowd, T. & Fortin, M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD006560. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub4 (2021).

Van den Bussche, H. et al. Umfang und Typologie der Häufignutzung in der vertragsärztlichen Versorgung der älteren Bevölkerung - Eine Analyse auf der Basis von GKV-Abrechnungsdaten. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen (ZEFQ) 107(7), 435–441 (2013).

Scherer et al. DEGAM S3 Leitlinie Multimorbidität. Stand 02/2017. https://www.degam.de/files/Inhalte/Leitlinien-Inhalte/Dokumente/DEGAM-S3-Leitlinien/053-047_Multimorbiditaet/053-047l_%20Multimorbiditaet_redakt_24-1-18.pdf; last acces: 2021_10_20.

Ho, I. S. et al. Examining variation in the measurement of multimorbidity in research: A systematic review of 566 studies. Lancet Public Health 6(8), e587–e597. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00107-9 (2021).

Cairo Notari, S. et al. Understanding GPs’ clinical reasoning processes involved in managing patients suffering from multimorbidity: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative research. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75(9), e14187. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14187 (2021).

Søndergaard, E. et al. Problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity: General practitioners’ views and attitudes. Scand. J. Prim Health Care 33, 121–126 (2015).

Stewart, M., Fortin, M., Britt, H. C., Harrison, C. M. & Maddocks, H. L. Comparisons of multi-morbidity in family practice—issues and biases. Fam. Pract. 30, 473–480 (2013).

Tinetti, M. E., Fried, T. R. & Boyd, C. M. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition–multimorbidity. JAMA 307(23), 2493–2494. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5265 (2012).

Lefevre, T. et al. What do we mean by multimorbidity? An analysis of the literature on multimorbidity measures, associated factors, and impact on health services organization. Revue d’Epidemiuologie et de Sante Publique 62, 305–314 (2014).

Kadambi, S., Abdallah, M. & Loh, K. P. Multimorbidity, function, and cognition in aging. Clin. Geriatr Med. 36(4), 569–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2020.06.002 (2020) (Epub 2020 Aug 16).

Burvill, P. W., Mowry, B. & Hall, W. D. Quantification of physical illness in psychiatric research in the elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 5, 161–170 (1990).

Linden, M. et al. Abschlussbericht zum Forschungsprojekt ‚Reha in der Hausarztpraxis‘. Forschungsgruppe Psychosomatische Rehabilitation Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund, 2012).

Mohammadibakhsh, R., Aryankhesal, A., Jafari, M. & Damari, B. Family physician model in the health system of selected countries: A comparative study summary. J. Educ. Health Promot. 9, 160. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_709_19 (2020).

Muschalla, B., Kessler, U., Schwantes, U. & Linden, M. Rehabilitationsbedarf bei Hausarztpatienten mit psychischen Störungen. Rehabilitation 52, 251–256 (2013).

Golino, H. F. & Epskamp, S. Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. PLoS ONE 12(6), e0174035 (2017).

Golino HF, Christensen AP, Moulder R, Ganet E. Exploratory Graph Analysis: A framework for estimating the number of dimensions in multivariate data using network psychometrics. R package version 0.9.8. 2020; 2.

Wicke, F., Karimova, K., Kaufmann-Kolle, P., Gerlach, F. M. & Beyer, M. Family physician-centered healthcare for patients with cardiovascular conditions—Results from Germany. Z. Allg. Med. 94, 454–461 (2018).

Muth, C. et al. Multimorbidity’s research challenges and priorities from a clinical perspective: The case of ‘Mr Curran’. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 20, 139–147 (2014).

Muth, C. et al. The Ariadne principles: How to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 12(1), 223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0223-1 (2014).

Funding

The study was supported by a research grant from the Federal German Pension Agency. Az.: 8011-106-31/31.51.6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. designed the study, did statistics and wrote the manuscript; U.L. contributed to study design, analysis and manuscript; D.G. did advanced statistics and contributed to the manuscript; J.G. contributed to study design, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Linden, M., Linden, U., Goretzko, D. et al. Prevalence and pattern of acute and chronic multimorbidity across all body systems and age groups in primary health care. Sci Rep 12, 272 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04256-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04256-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.