Abstract

Cassava, a food security crop in Africa, is grown throughout the tropics and subtropics. Although cassava can provide high productivity in suboptimal conditions, the yield in Africa is substantially lower than in other geographies. The yield gap is attributable to many challenges faced by cassava in Africa, including susceptibility to diseases and poor soil conditions. In this study, we carried out 3’RNA sequencing on 150 accessions from the National Crops Resources Research Institute, Uganda for 5 tissue types, providing population-based transcriptomics resources to the research community in a web-based queryable cassava expression atlas. Differential expression and weighted gene co-expression network analysis were performed to detect 8820 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs), revealing similarity in expression patterns between tissue types and the clustering of detected DEGs into 18 gene modules. As a confirmation of data quality, differential expression and pathway analysis targeting cassava mosaic disease (CMD) identified 27 genes observed in the plant–pathogen interaction pathway, several previously identified CMD resistance genes, and two peroxidase family proteins different from the CMD2 gene. Present research work represents a novel resource towards understanding complex traits at expression and molecular levels for the development of resistant and high-yielding cassava varieties, as exemplified with CMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), a staple for over 800 million people worldwide, is cultivated across the tropics, with Africa accounting for over 50% of the total world production. Yield in Africa has remained substantially lower compared to other regions where cassava is grown1. Cassava has become a multipurpose crop with the ability to respond to the challenge of climate change and the potential to respond to priorities of developing countries including food security, poverty alleviation and economic development1. Most agronomic and production traits, such as yield, quality and disease-related traits, have become part of the primary breeding objective of a cassava breeding program and define the adoption of new cassava varieties by farmers and the market value of harvested roots2,3. The improvement of agronomic and production traits are enabled by improved understanding of the development and physiology characteristics of cassava, as reported for “leaf natural shading” using transcriptomics approach4. Transcriptomics is an approach that uses deep sequencing technologies such as the RNA-seq to profile transcriptomes, representing the complete set of transcripts in a cell5. Techniques such as transcriptomics can also be used to study plant diseases, such as Cassava mosaic disease (CMD). CMD, a major constraint to cassava production in Africa, Thailand and the Indian subcontinent6,7, with a yield loss of up to 95%, can be kept under control with the deployment of resistant varieties8. CMD is caused by several related species of cassava mosaic geminivirus (CGMs) and transmitted through infected cuttings and by a vector commonly known as whitefly (Bemisia tabaci G.). While much progress has been made on CMD, currently utilized resistance relies on single-gene resistance from related landraces. The narrow genetic base resistance could potentially break down over time, given their long-term effectiveness and the potential to be overcome by CGMs because of their fast-paced evolutionary rate9,10. On the other hand, the genetic mechanism of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD)—a threat to economic and food security for smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa—is yet to be fully understood11, due to the difficulty in phenotyping the disease12 and the complex nature of CBSD virus resistance13. Recent efforts on identifying sources of resistance to CBSD using transcriptomics have been based on individual contrasting varieties13,14. Previous studies utilizing whole transcript sequencing technology to characterize and quantify transcripts have relied on comparison of transcriptomes allowing the identification of genes that are differentially expressed in response to individuals treated differently or individuals with contrasting characters of interest15. Fragmentation and library construction can introduce biases in whole transcript sequencing, bringing about more reads being assigned to a longer transcript than a shorter transcript, given that longer transcripts are sheared into more fragments5. The bias of fragmentation has been shown to enrich the differential expression of genes with longer transcripts16. 3′-RNA sequencing now provides a lower-cost and higher-throughput alternative to whole transcript sequencing, minimizing the aforementioned bias, and has been shown to have similar reproducibility and the ability to detect shorter transcripts17. Although the RNA sequencing methodology assigned more reads to longer transcripts when compared to the 3′-RNA sequencing methodology according to differential expression analysis, the RNA sequencing traditional method detects more differentially expressed genes, regardless of the level of sequencing depth17. This study is the first to use 3′-RNA sequencing technology in cassava, in a manner similar to earlier applications in maize18. For most complex traits, multiple small effect genetic variants can play a significant role in explaining trait variation when compared to simpler traits with rare monogenic mutations of large effects19. Therefore, analyzing gene expression levels of multiple tissues on a population basis would establish a high-resolution transcriptome resource for eQTL detection or trait prediction.

We present a population-based transcriptomic resource and expression atlas visualization for a population consisting of 150 cassava accessions sampled across five tissues (leaf, stem, fibrous root, storage root, flower) for studies of complex traits in the cassava community. The objectives of this study were to (1) quantify expression of transcripts across five tissues for 150 accessions, (2) make this data resource available to the community in a web-based queryable cassava expression atlas, (3) conduct differential gene expression analysis to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across our population, with which we carried out weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) and Gene Ontology (GO) analysis to characterize genes detected in different modules or co-expressed clusters, (iv) confirm data quality by differential gene expression and GO analysis carried out on clones differing for CMD tolerance. Altogether this work provides a population-based transcriptomics resource with a wide range of applications and can be leveraged for studies of simple and complex traits in cassava.

Results

Principal component analysis (PCA) highlights the clustering of different tissue types

RNA expressions from 150 accessions were quantified using the 3′-RNA sequencing method20. Five tissue types were profiled including storage root, fibrous root, stem, leaf, and flower for 150 cassava accessions, giving a total of 750 samples. PCA was performed to determine sample clustering. Using the variance stabilizing transformation (vst) normalized gene-level counts from HTSeq (Supplementary Table S1), PCA results indicated that samples of the same tissue types clustered together with PC1 and PC2 explaining 25.6 and 9.8% of the total variance in the gene expression across all tissues (Fig. 1a). For cassava accessions that did not flower at the time of sample collection or as a result of asynchronous flowering, tissue samples collected from their apical meristem clustered together with samples from flower tissues. Apical meristem tissue types were merged to flower tissue type for further downstream analysis. In agreement with PCA observations, heatmap and hierarchical clustering across the five tissue types demonstrated the same tissue type clustering and expression patterns (Fig. 1b).

Principal component analysis and heatmap visualization of variance stabilizing transformation (vst) normalized gene-level counts for 31,895 genes across five different tissues (storage root, fibrous root, flower + apical meristem, stem and leaf). (A) Principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) were estimated using the prcomp function in R. The total variance explained by PC1 and PC2 is shown. (B) Heatmap of genes across different tissue types. Since apical meristem clustered with flower tissue type and was collected for accessions that did not flower, tissue samples from apical meristem were added to flower tissue types.

Cassava expression atlas (CEA), a tool for visualizing quantified transcriptomes

The cassava expression atlas was implemented on cassavabase (https://cassavabase.org), an open-source digital ecosystem dedicated to the cassava research community21,22. Cassavabase provides a tool suite to assist breeders and breeding programs in automating their routine breeding and pre-breeding activities. Counts per million mapped reads (CPM) obtained from HTSeq gene-level counts normalized using EdgeR23 were used as digital units of expression for visualization of transcript expression levels (see Supplementary Table S2 for CPM values). Supplementary Fig. S1 provides a brief guide for using CEA functions. The CEA gene discovery search results include expression cube, expression images, heatmap and scatter plot features. To demonstrate CEA functions, we selected a random gene (Manes.01G011400.v6.1) and four accessions, and went through the process described in Supplementary Fig. S1 legend. The results from the different features are highlighted in Fig. 2. Figure 2 represents the expression cube, heatmap, images and barplot of the different tissue types for the gene of interest and other genes correlated to it, based on \(r^{2}\) correlation coefficient of 0.65 and above.

Cassava expression atlas (CEA) visualization output for four accessions (F10, Nam130, Mkumba, Pwani) and the Manes.01G011400 gene. (A) Expression atlas cube showing the expression of five tissue types on four accessions for Manes.01G011400 gene and other genes that are correlated to the gene of interest. (B) Heatmap of the expression of five tissue types on four accessions for Manes.01G011400 gene. (C) Expression images of five tissue types on four accessions for Manes.01G011400 gene. (D) Barplots showing the expression of five tissue types on four accessions for Manes.01G011400 gene.

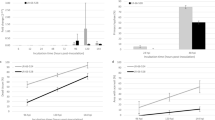

Differential expression analysis identifies genes involved in systemic acquired resistance

To quantitatively evaluate and compare transcript levels between tissue types, differential expression analysis was carried out using DESeq2 across the 150 accessions in our population. On average, 31,895 genes were mapped to at least one read in each of the tissue samples (Supplementary Table S3). A total of 19,445 DEGs were detected across pairwise tissue comparisons using an adjusted p value of < 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. S2 and S3, Supplementary Table S4), yielding a maximum of 9225 (storage root vs. leaf, annotated as TvL) and a minimum of 3330 (stem vs. fibrous root) DEGs (Fig. 3a). However, for downstream analysis, a unique set of 8820 unique DEGs were selected out of the 19,445 detected DEGs (Supplementary Table S5). The comparison of DEGs identified across contrasted tissue types show overlap of genes commonly expressed across contrasted groups, with larger numbers of genes overlapping across all contrasted groups for any specific tissue type (43.06–56.74%) (Fig. 3b–f). As a quality assessment positive control step, visualization of Rubisco methyltransferase family protein and Rubisco activase protein on CEA in a comparison between storage root versus leaf tissue types show that they are significantly differentially expressed (Supplementary Fig. S4). These genes are known to be housekeeping genes; Rubisco methyltransferase family protein and Rubisco activase protein24. Both proteins were significantly highly expressed in the leaf compared to other tissue types (Supplementary Fig. S4), as previously reported for Arabidopsis thaliana25.

Detected differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across tissue types comparisons. (A) barplot showing detected DEGs across pairwise tissue types (SvsF stem vs flower, SvsT stem vs storageRoot, FvsT flower vs StorageRoot, TvsFR storageRoot vs fibrousRoot, FvsL flower vs leaf, SvsL stem vs leaf, TvsL storageRoot vs leaf, FRvsL fibrousRoot vs leaf). (B–F) Overlaps of detected DEGs for different tissue type comparisons.

In order to confirm the high quality of our dataset, we carried out differential expression analysis between Mkumba and NASE14. Mkumba is a CMD resistant variety, while NASE14 expresses CMD2-mediated resistance as a mechanism for CMD resistance26. The implication of the CMD2-mediated resistance mechanism is that before the R-gene is activated, CMD viral infection leads to numerous molecular and physiological changes that can lead to limited symptom expression. Molecular screening indicated that resistant cultivars showed CMD symptoms at the early growth stages but the disease did not advance because of the presence of the CMD2 resistance gene27. The samples used in this study were collected at early growth stages with the aim of quantifying gene expressions, hence NASE14 was used as the “susceptible” variety. Since the effector triggered immunity was yet to be triggered but was rather at the phase of effector triggered susceptibility thus explaining the gene changes that typically occur in a susceptible clone28.

A total of 241 DEGs were detected between Mkumba and NASE14, based on adjusted p value of < 0.05, with 13% (321) and 87% (2220) DEGs upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S6). KEGG29,30 gene enrichment pathway analysis on the detected DEGs, identified genes (highlighted using red star) involved in the Plant–pathogen interaction pathway (27 DEGs; 1.6 fold enrichment) based on p value of < 0.05 (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S7). In the plant–pathogen interaction map, only two nodes (MKK1/2 and HSP90) were upregulated, the other 10 nodes were downregulated (Fig. 5a,c) based on log2 fold change. Hierarchical clustering of these identified plant–pathogen interaction pathway genes showed three clusters of genes based on their expression patterns across the gene clusters, with distinct expression across different tissue types (Fig. 5b). Other identified pathways included Pyruvate metabolism (15 DEGs), Base excision repair (9 DEGs) and Peroxime pathways with respective fold enrichments of 2.0, 2.4, and 1.8, and p value of < 0.05. Based on Bonferroni multiple test correction of < 0.05, KEGG biological processes GO terms, showed that response to chitin was significantly enriched with 2.6 fold enrichment, and molecular function GO terms showed that protein binding, helicase activity, ATP binding, and metal ion binding were significantly enriched with fold enrichment of 1.4, 3.1, 1.3, and 1.3, respectively.

Differential expression between Mkumba vs Nase14, heatmap of hierarchical clustering and phylogenetics analysis of CMD associated peroxidase genes. (A) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes. Some of the gene names were printed on the plots. NS = not significant; Log2 FC = significant DEGs above the threshold of >|1| log2 fold change; P = significant DEGs based on adjusted p value of < 0.05; P & Log2 FC = significant DEGs based on adjusted p value of < 0.05 and threshold of >|1| log2 fold change. The gene (Manes.10G147700) in the top left is a Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein/seed storage 2S albumin superfamily protein. Inserted are Expression atlas cube [above gene name] and barplot [below gene name] showing the expression of five tissue types on two accessions for Manes.10G147700 gene. (B) Heatmap for 27 genes involved in transmembrane transport activities in the yellow module with the genes and their corresponding description. The heatmap shows two broad characterizations. (C) Phylogeny of two differentially expressed peroxidase gene families and the two from GWAS analysis associated with CMD resistance in cassava10.

Plant–pathogen interaction pathway, Heatmap of hierarchical clustering of the 27 DEGs in the pathway and cassava expression atlas (CEA) barplot of selected genes. (A) Observed plant–pathogen interaction pathway using the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. Proteins present in the CMD DEGs are marked with red stars. Proteins marked in green belong to the reference-organism path. The plant–pathogen interaction pathway reveals sets of genes involved in the plant immune response. The gene MKK1/2 and HSP90 were upregulated, while the rest of the observed genes in the pathway were downregulated based on log2 fold change. MKK1/2 and HSP90 shows down- and up-regulations in a CMD susceptible and resistant accessions, respectively. The functions of these genes included potential calcium sensors (AGD11, CML, CAM), hydrogen peroxide generation during hypersensitive response-like cell death (MKK5), and disease resistance pathogen recognition protein that triggers a defense system including the hypersensitive response, which restricts the pathogen growth (RPS2)84. Others were genes that produce nitric oxide, a messenger molecule involved in hormonal signaling and defense responses in plants (NOA1); a protein kinase gene, involved in plant defense responses specifically recognizing effector avirulence protein and triggering a defense reaction (RPS5); and a gene that is an essential regulator of plant defense, which plays a central role in resistance in case of infection by a pathogen (RIN4). Additional genes in the pathway are involved in transcription, interacting with the W box (5′-(T)TGAC[CT]-3′) (WRKY2); and a gene that generates reactive oxygen species during incompatible interactions with pathogens and is important in the regulation of the hypersensitive response (RBOH F). (B) Heatmap of hierarchical clustering for the 27 genes observed in the plant–pathogen interaction pathway using KEGG enrichment analysis. (C) Barplot of selected genes in the plant–pathogen interaction pathway showing the pattern of gene expression for genes that are upregulated and downregulated for CMD susceptible (based on CMD2 resistance-NASE14) and resistant (Mkumba) accessions.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of the detected 8,820 unique DEGs identified 18 gene modules

WGCNA was carried out using the 8820 DEGs obtained from comparison of different tissue types for construction of a scale-free co-expression network. These 8820 DEGs showed distinct expressions across different tissue types (Fig. 6a). The weighted coefficient parameter β = 7 was chosen to obtain a correlation coefficient of 0.93 (Supplementary Fig. S6). A hierarchical tree function was used to divide the constructed clustered tree, detecting 18 co-expression modules, each tagged with a color, including turquoise with maximum number of 2848 DEGs, light green with minimum number of 39 DEGs and a yellow module with 307 DEGs (see all modules in Fig. 6b–d, Supplementary Fig. S7a and Supplementary Table S8).

Heatmap of hierarchical clustering analysis and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). (A) Heatmap of 8820 DEGs across different tissue types. (B) Gene co-expression modules showing the cluster dendrogram constructed based on the eigengenes of the modules (upper panel) and the heatmap for the correlation coefficient between the modules (lower panel). (C) Barplot showing the approximate percentage distributions of DEGs clustered into 18 gene modules using the WGCNA R package. (D) Expression patterns of genes as they are clustered based on detected modules and different tissue types. Genes in the grey module are usually genes that did not cluster with genes in any of the 18 modules.

Given that the yellow module with 307 DEGs contains the Manes.10G147700 gene, characterized to be involved in CMD resistance, we subjected it to further analysis. First, we functionally classified the genes in the yellow module based on (1) molecular function, (2) biological function, (3) cellular components, (4) protein classes and (5) pathway categories using PANTHER classification system version 16.031 with corresponding Arabidopsis thaliana annotation IDs from the cassava version 6.1 annotation genome32.

The molecular function categories observed for genes in the yellow module included Binding (GO:0005488), Catalytic activity (GO:0003824), Molecular function regulator (GO:0098772) and Transporter activity (GO:0005215) with 23%, 58.4%, 7.1% and 11.5% genes in each category, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S7b). The categories of protein classes represented in the yellow module included genes encoding metabolite interconversion enzymes (PC00262), transporters (PC00227) and gene-specific transcriptional regulators (PC00264) with 63%, 10.6%, and 8.55% genes in each category, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8a). The biological process GO term categories for genes in the yellow module included cellular processes (GO:0009987), metabolic processes (GO:0008152) and biological regulations (GO:0065007) with 34%, 30.5% and 10.6% genes in each category, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8b). The cellular component GO terms categories observed in the yellow module included cellular anatomical entities (GO:0110165) and intercellular activities (GO:0005622) with 58.3% and 39.6% of genes for each category, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8c). Pathway characterization shows that genes in the yellow module fall within categories including glycolysis (P00024), fructose galactose metabolism (P02744), pentose phosphate pathway (P02762), and vitamin B6 metabolism (P02787) with gene percentage of 21.1%, 10.5%, 10.5%, 10.5%, and 5.3%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8d). Other pathway categories included cholesterol (P00014), cysteine (P02737), serine glycine (P02776), and tyrosine (P02784) biosynthesis, all at 5.3% of genes in the yellow module (Supplementary Fig. S8d).

Second, the yellow module analysis for enriched GO terms was conducted for (1) biological processes, (2) molecular functions and (3) cellular components based on the Bonferroni-corrected p value of < 0.05. The statistically significant enriched terms indicated that genes in the yellow module were mostly involved in biological processes of sporopollenin biosynthesis (p value = 2.69E−06), anther wall tapetum development (p value = 0.0065), cuticle development (p value = 0.0045), cellular carbohydrate catabolic process (p value = 0.00086), and starch metabolic process (p value = 0.0064; Table 1) (with all GO lists in Supplementary Table S9). For molecular function GO terms, genes in the yellow module were mostly involved in sugar transmembrane transporter activity (p value = 0.0036), oxidoreductase activity (p value = 0.01), iron ion binding and heme binding (p value = 0.01). For cellular component enriched GO terms, integral component of plasma membrane (p value = 0.033), plant-type cell wall (p value = 0.0006) and protein-containing complex (p value = 0.0007) were statistically significantly enriched terms for genes in the yellow module (Supplementary Table S9).

A set of 27 genes from the yellow module were found to be involved in transmembrane transporter activities in the molecular function GO using PANTHER gene enrichment tool with Fisher’s exact test and Bonferroni correction for multiple testing for p value of < 0.05, included Manes.16G007900, a MATE transporter, earlier reported to be involved in the regulation of cyanogenic glucosides in cassava root33 (Table 2). The expression pattern of these sets of 27 genes shows at least two broad groups with genes mostly involved in detoxification found in the upper half (Fig. 4b). The GO term enrichment results for all detected modules are described in Supplementary Table S10.

Genetic variance explained by SNP markers in the detected 8,820 DEG regions

Evaluating the functional relevance of the detected DEGs, proportion of variance explained by SNPs in the DEG regions was higher for vigor (DEG SNPs: 0.24, sampled SNPs: 0.12), a fitness trait and dry matter (DM) content (DEG SNPs: 0.38, sampled SNPs: 0.32), an agronomic trait when compared to randomly selected SNPs (excluding SNPs in high LD with the DEG SNPs) of equal size and distribution (Supplementary Fig. S10). For other agronomic and disease related traits, SNPs within the DEG regions explained less variance when compared to the randomly sampled SNPs of equal sizes and distribution. While fitness related traits respond to gene regulation (though fresh root yield does not respond in that manner based on this dataset), disease resistance in plants has been shown not to be influenced by differential expression but rather by genes that are involved in disease infection recognition18,34,35. This is also highlighted by the SNPs in the DEG regions explaining about twice the variance explained by the rest of the genome (11,399 DEG-SNPs: 0.23; 65,054 Other-SNPs: 0.13) for plant vigor trait.

Discussion

The multifaceted ability of cassava to respond to both the challenge of climate change and the priorities of developing countries makes cassava a sustainable and reliable crop for food security, poverty alleviation and economic development1. However, the cassava yield gap in the developing countries compared to other regions where cassava is grown highlights the necessity for better understanding of the cassava developmental and physiological processes. This will allow further improvements in complex traits including yield, quality, fitness and disease resistance-related traits in Sub-Saharan Africa. Here, we aimed to provide a population-based transcriptomics resource for studies of complex traits to assist cassava improvement efforts.

Expression of transcripts for 150 accessions from the Ugandan cassava breeding program were quantified, with sampling performed on flower, leaf, stem, fibrous and storage root tissues for each accession. A 3′-RNA sequencing method was chosen, which has been shown to be more efficient than RNA sequencing in the way it handles paralogs20. Multivariate analysis shows the clustering of each tissue type together. PCA outputs split variance according to distinct biological parameters, with PC1 highlighting the variance due to different tissue types, while PC2 likely explains the genetic differences between the accessions in the population. Similar observations were made using a heatmap hierarchical clustering algorithm, supporting our earlier PCA observation and highlighting similarities in the pattern of expression between tissue types, with the storage root having a closer expression pattern to the fibrous root, while the leaf had a similar expression profile to the stem tissue. The resolution of the different tissue types into distinct clusters indicated the high quality of the dataset, and highlights that the quantified transcripts captured transcriptional differences in the tissue types and the physical relatedness between tissue types. A similar clustering pattern was previously reported for cassava among tissue types15.

Differential expression results and overlapping of identified DEGs between contrasting tissue type comparisons, highlight common DEGs across comparisons and indicate the abundance of house-keeping genes and smaller percentage of genes that are unique or specific to a set of contrasted tissue types. In addition, it was observed that tissue types with similar expression patterns had fewer DEGs than those having more distinct expression patterns. For example, stem versus fibrous root tissue comparison gave the least number of DEGs (3330), followed by storage root versus fibrous root comparison with 3676 DEGs, while comparison of storage root versus leaf tissue gave the highest number of DEGs (9225). This observation is consistent, supports our PCA and hierarchical clustering results, and represents the first study in cassava that looked at the comparative expression patterns of major organs/tissues using a population-based approach. In addition, expression patterns of the detected modules by tissue types seem to suggest modules/genes that could be targeted for cassava improvements based on traits and contrasting tissue types of interest. This highlights how genes within a module are differentially expressed across different tissue types. For example, genes in the brown module show that flower tissues had distinct expression patterns compared to the rest of the tissue types, while genes in the blue module show that leaf tissues had distinct expression patterns compared to the rest of the tissue types.

The classification of the genes in the yellow module indicates that they are mostly involved in regulatory functions such as RNA- and DNA-binding transcription and other transcription factors required for the regulation of many cellular processes, including transcription, translation, gene silencing, gene expression control, catalysis and similar functions36. Other genes in the yellow module are involved in transport activities, allowing the transfer of substances (sugar, copper, sulfate, potassium, iron) across plasma membranes, enabling activities such as detoxification as earlier described for cyanogenic glucosides in cassava33.

GO term enrichment (over-representation) analysis showed that genes in the yellow module are involved in both molecular, cellular and biological functional processes. Notable among them are the sugar transmembrane transporter activity, integral component of plasma membrane and sporopollenin biosynthetic process with the most upregulated fold enrichment, supporting the earlier speculation that most genes in this module are mostly associated with plant developmental processes. While Manes.10G147700 found in the yellow module, involved in plant defense against cassava mosaic virus and its insect vector whitefly, is characterized to be involved in lipid transport/protein metabolism based on functional GO terms. The cassava root HCN regulation gene (Manes.16G007900) also found in the yellow module, and part of the transmembrane transport activity GO term, supports the speculation that genes in the yellow module are functionally involved in developmental processes. Manes.16G007900 is a MATE transporter that may be involved in the regulation of cyanogenic glucosides such as linamarin and lotaustralin in cassava root33. Linamarin, an abundant cyanogenic glucoside variant in cassava and a secondary metabolite, contains nitrogen and serves as a nitrogen shuttling and storage compound37. Nitrogen is a vital and major component of chlorophyll used as an energy source to produce sugar, a major component of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, and together they ensure the survival and development of a plant38.

Twenty-seven transporter genes from the yellow module, characterized to be involved in transmembrane transporter activity based on molecular function GO terms, facilitates transfer of a specific substance or group of related substances, from one side of a membrane to the other39. The expression pattern of these 27 transmembrane transporters indicated two broad categories: those likely involved in allowing the uptake of essential nutrients and those involved in secretion of metabolic end products and hazardous substances. Among those already characterized in cassava are Manes.15G030700 involved in galactose transport40 and Manes.16G007900 involved in cyanogenic glucoside transport33. However, the phosphoserine aminotransferase family gene (Manes.02G112800—phosphoserine transaminase), identified to be involved in vitamin B6 metabolism, has not been previously characterized in cassava. Six genes in the yellow module characterized by PANTHER biological process GO appear to be involved in the starch metabolic processes, and two were previously characterized as being involved in the starch biosynthetic pathway in cassava41,42.

Differential expression results were further investigated for CMD tolerance. DEGs detected encoding NBS (Nucleotide Binding Site) and TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor) regions were previously described by Lopez et al. as resistance gene candidates in cassava43. Eleven (11% R genes) out of the 99 resistance analogues genes reported by Allie et al. to respond to cassava mosaic virus infection were among the detected DEGs44 (Supplementary Table S11). The eleven R genes included leucine-rich repeat (LRR) transmembrane protein kinase and NB-ARC domain-containing disease resistance protein, disease resistance protein (TIR-NBS-LRR class) family and Histone superfamily protein. Previous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on CMD resistance in African cassava identified two closely linked genes on chromosome 12, Manes.12G076200 and Manes.12G076300, both identified as peroxidase superfamily proteins to be involved in the regulation of CMD9,10. One is characterized as CMD2 and the second is a “highly correlated peroxidase gene about 17 kilobases away”45,46,47,48,49. However, neither of these peroxidase genes were differentially expressed in our dataset, despite the fact that they were characterized as pathogenesis-related proteins involved in host response to infection50 and downregulated in response to CMD infection in susceptible accessions44. Surprisingly, we found two different peroxidase superfamily proteins, Manes.03G063400 (log2 fold change: − 2.7919) and Manes.17G124300 (log2 fold change: 9.0907), located on chromosomes 3 and 17, respectively to be significantly differentially expressed. The percentage sequence similarity of the CMD2 gene to Manes.03G063400 and Manes.17G124300 genes was 52.80% and 52.73%, and that of Manes.12G076300 to Manes.03G063400 and Manes.17G124300 genes were 53.06% and 48.12%, respectively. With an average of 50% pairwise sequence similarity across homologs (Fig. 4c), the significance of these findings will require additional investigation to ascertain if these genes are involved in CMD response.

Coincidentally, based on an optimal adjusted p value (7.45E−45) and log2 fold change (− 40.13), we identified a lipid-transfer protein (Manes.10G147700), previously reported to be involved in plant defense against cassava mosaic virus and its insect vector whitefly8,10. Vidya et al. used the Nucleotide Binding Site transcriptome profiling technique with the aim of identifying CMD resistance genes in India8. A total of 24 genes (27 DEGs with homologs) out of the 105 candidates genes reported to be associated with CMD resistance by Wolfe et al. were part of our DEGs, including Manes.10G147700 reported to be a candidate gene associated with CMD resistance when phenotyped at three months after planting (CMD3S)10 (Supplementary Table S11). These 24 genes reported by Wolfe et al., are associated with CMD resistance across all phenotyping time points (CMD1S, CMD3S, CMD6S, CMD9S)10. Manes.10G147700 was expressed in flower tissue and at a lower level in the stem of a susceptible cassava variety (see Fig. 4a inserted CEA cube and barplot), similar to the expression pattern observed in its Arabidopsis homolog (AT3G52130)51. Manes.10G147700 is a non-specific lipid transfer protein (nsLTP) with the ability to transfer lipids across membranes52. nsLTP has been previously described in Arabidopsis, maize, spinach, castor bean, wheat53 and only recently reported to be involved in CMD resistance in cassava8. A non-specific lipid transfer protein, encoded by large gene families in many flowering plants54, binds to sterol molecules to trigger plant defense response by interacting with a receptor at the plant plasma membrane55 and usually detected during early development in plants56. This protein was previously implicated in plant defense against viral, fungal and bacterial pathogens in plants57. Other identified DEGs included heat shock proteins also reported to be required for the resistance mediated by R proteins8. These findings on CMD resistance in cassava (1) further highlight the complexity of cassava mosaic disease and the fact that current qualitative methods of CMD phenotyping do not provide enough information to decipher the molecular relationship between genotype and phenotype, given that CMD2 gene was not differentially expressed. These findings are similar to what has been previously reported for CBSD58. (2) In addition, this could also be attributed to the fact that the CMD2 gene is not expressed on any of the five cassava tissues in this study (as seen in Supplementary Fig. S9b—right side), as previously speculated by Adenike et al59. Previous studies on CMD resistance highlighted a single source of monogenic resistance in the cassava genepool60, especially in Africa. The findings in this study provide the foundation for a more in-depth, quantitative understanding of resistance and support the long term goal of diversifying the sources of resistance, given the precarious nature of single gene resistance9,10.

Conclusion

While transcriptomics has relied on contrasting individuals, our study provides a population-based resource, unique to previously described available transcriptomics cassava resources. Resources including genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, epigenomics and proteomics to support cassava improvement and intensification have been previously described15,32,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. In this study, we characterized the transcriptomics of 150 accessions across five different tissue types. The expression dataset highlights the similarity in expression pattern between tissue types, indicating that tissue types that are physically closely related seem to have similar expression patterns. We detected 19,445 DEGs with 8820 DEGs unique across tissue types comparisons and further characterization detected 18 modules, in which the HCN cassava root regulation transporter, the galactose transporter and the plant defence gene against cassava mosaic virus and its insect vector whitefly, were all located in the yellow module, based on previous characterization in cassava. The yellow module is widely involved in developmental processes and highlights important regulatory genes in cassava. These 307 genes in the yellow module, highly enriched in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and metabolic pathway processes, represent important genes for studying physiology and developmental characters for cassava improvement. We provided further insight on CMD resistance and highlighted sets of 27 genes that were involved in the plant–pathogen interaction pathway. Our study suggests a potential path to sources of CMD resistance diversification and provides a queryable cassava expression atlas that will serve as a valuable and novel population-based resource to the cassava research community. These resources can be used to develop a biological information driven genomic selection (GS) framework to further improve prediction accuracies, especially for disease traits, which could leverage spatial and temporal control of plant pathogen response to facilitate breeding for crop improvement in cassava. Other applications include differential gene expression analysis to quantitatively evaluate transcript levels between tissue types or contrasting individuals of interest and performing expression quantitative trait loci to identify genomic loci explaining variation in expression levels of mRNAs for traits of interest. In the future, a validation study of the Manes.10G147700 gene using analysis of promoters or knock-outs would be required to understand its relationship with the CMD phenotype. The combination of these approaches would provide information on the specific functioning of Manes.10G147700 to CMD inoculation at different developmental stages.

Methods

Tissue sample collection, RNA extraction, RNA-seq library preparation and Illumina sequencing

Tissue samples were collected from 150 accessions across five tissues at a cassava experimental field at National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) Kampala, Uganda. Dr. Robert Kawuki undertook the formal development and identification of the cassava accessions used in this study. These accessions are part of the genetic gain populations of NaCRRI10, and publicly available on https://cassavabase.org. For most of the accessions, samples were collected from leaf, stem, fibrous root, storage root and flower tissues; while for accessions that were not flowering, apical meristem tissue was collected in place of flowers. RNA was extracted using TRIzol by Invitrogen protocol, in which hot borate and lithium chloride were used to extract RNA from tissue samples of leaf, flower, stem, fibrous and storage root72. 3′RNA-seq libraries were prepared according to the method described by Kremling et al18. Briefly, libraries were prepared robotically, using 96-well plates from 500 ng total RNA on an NXp liquid handler using QuantSeq FWD kits. Post-PCR cleanup was performed and libraries were pooled to 96-plex according to the QuantSeq protocol. Molar concentrations were calculated for each pool and sequenced using 90 nucleotide single-end read Illumina TruSeq primers on an Illumina NextSeq 500 with v2 chemistry in the year 2015 at the Cornell University Sequencing facility. Normalized gene-leve counts and raw sequencing datasets were deposited on https://cassavabase.org, hosted at ftp://ftp.cassavabase.org/Cassava3primeRNAseqRawReads/. Raw sequencing data were submitted to NCBI sequence reads archive (SRA) with the following details (BioProject: PRJNA737128) and can be accessed via http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/737128.

3’RNA-seq dataset processing

Fastq files for each sample were processed using Trimmomatic73 (version 0.32) to remove the first 12 bp and remnants of the Illumina Truseq adapter from each read according to kit maker recommendation. The STAR aligner74 (version 2.7) was used to align reads against cassava version 6.1 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Mesculenta) genome annotation using parameters that included (-outFilterMultimapNmax 10; -outFilterMismatchNoverLmax 0.04; -outFilterIntronMotifs RemoveNoncanonicalUnannotated), allowing reads to map in 10 locations, with at most 4% mismatches, and filtering out all non-canonical intron motifs. HTSeq75 (version 0.11.2) default settings were used to obtain gene-level counts, which were then normalized using the counts per million mapped reads (CPM) method implemented in the EdgeR23 (version 3.26.8) package in R version 3.6.3 (2020-02-29). The normalized CPM expression digital values were used for visualization in a cassava expression atlas76 (https://cea.sgn.cornell.edu/expression_viewer/input) hosted on cassavabase.org (https://cassavabase.org) (see Supplementary Fig. S11 for data processing schema). Obtained gene-level counts from HTSeq75 were normalized using variance stabilizing transformation77 (vst) method in DESeq277 (version 1.24.0) for downstream analysis including principal component analysis (PCA) and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)78.

Cassava expression atlas data availability

The cassava expression atlas graphical interface was implemented on cassavabase.org to allow for the interactive visualization and exploration of tissue-specific patterns and discovery of trends in a population-based transcriptomics dataset76. The implementation uses CPM normalized read counts obtained from HTSeq75 (version 0.11.2), functional gene annotations from Phytozome (version 10.3), and analysis of correlation of genes using the cor function in R 3.4.2 (R. Core Team, 2015). The expression atlas has four main features: expression cube, expression images, heatmap and scatter plot. The expression cube enables gene discovery based on gene expression patterns across accessions and tissue types, with the ability to display genes with expression correlated to that of your gene of interest across the dataset. The expression images are whole cassava plant images showing tissue-specific expression patterns of selected or newly discovered genes across selected accessions. The heatmap is created to visualize tissue-specific expression patterns for selected genes across selected accessions. The scatter plot feature visualizes expression of any two samples. The cassava expression atlas can be found at: https://cassavabase.org and additional details can be found in the cassavabase.org manual.

Differential gene expression and weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Differential expression and statistical analysis were carried out using the DESeq277 (version 1.24.0) R package. DESeq2 uses raw read counts as input, corrects for library size and accounts for sequencing depth using vst normalization. To account for multiple testing corrections, p values were adjusted using Benjamini–Hochberg79 testing procedure and a false discovery rate adjusted p value of < 0.05 was used as a threshold for significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each differential expression analysis done in this study. As a quality assessment step, we profiled the expression of Rubisco as a positive control similar to housekeeping genes used in qPCR80. To assemble DEGs for downstream analysis, first we retrieved the detected DEGs for different pairwise tissue comparisons based on adjusted p value of < 0.05 and log2 fold change (log2FC) of >|1|. We then combined (union) all detected DEGs (19,445) from all comparisons and kept a total of 8,820 unique DEGs for downstream analysis. Previously reported resistance genes with cassava genome annotation versions earlier than version 6 were identified by BLAST search on phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!search?show=BLAST) using cassava genome version 6 annotation. Variance stabilizing transformation normalized gene-level counts from HTSeq for the 8820 selected unique DEGs were used to infer co-expression gene network modules using the WGCNA78 R package with power-law coefficient β selected using the soft-thresholding method and a hierarchical tree cut algorithm used in detecting the co-expression modules.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis

Genes identified in different modules from WGCNA were characterized for GO terms including biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions using over-representation Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni multiple testing correction p value of < 0.05 in PANTHER version 16.0 (Released 2020/07/28) as previously described10. The gene enrichment analysis was performed on the Arabidopsis thaliana GO database (GO Ontology database https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4081749 Released 2020-10-09)31 using corresponding cassava genome version 6.1 annotation IDs32 as previously described10. DEGs identified from differential expression analysis of CMD susceptible and resistant accessions were subjected to KEGG pathways enrichment analysis29,30. KEGG was used because it was easy to overlay identified genes on pathway maps available on the platform (Database last updated: January 18, 2021).

Partitioning proportion of genetic variance explained by markers on the DEG selected regions

Using parametric multiple kernel mixed model81 as previously described for cyanide33 and other traits in cassava, we calculated the heritability contribution of the SNP markers found within the regions (with 53,335 bp maximum transcript length) of the selected 8820 DEGs for traits fresh root yield (FYLD), vigor, root number (RTNO), dry matter (DM), mean CMD (MCMD), and mean CGM (MCGM). The variance explained by the markers in these regions was compared with a random set of markers of similar size and distribution across the genome. To ensure precise estimation of the proportion of variance explained, LD was controlled by removing markers that are in high LD (r2 ≥ 0.9) with the 11,399 SNPs in the DEG regions. We estimated the variance components using the ‘emmremlMultikernel’ function implemented in the R package EMMREML82. The multikernel model is represented in matrix notation: \(y = Xu + Zg_{1 } + Zg_{2 } + e\), where \(y\) is the vector of the best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) for each trait, and \(X\) is a vector of ones, representing the intercept. \(u\) is the genetic mean effect of DEG SNPs on a trait, and \(Z\) is the design matrix linking observations to individuals. \(g_{1} \;{\text{and}}\; g_{2}\) are the genetic variance components for SNPs in the DEG regions and sampled SNPs of equal size and distributions across the genome, respectively. Where \(g_{1} \sim N\left( {0,GRM_{D} \sigma^{2} } \right)\) and \(g_{2} \sim N\left( {0,GRM_{S} \sigma^{2} } \right)\) have known variance structure, calculated using DEG SNPs (\(GRM_{D}\)) or sampled SNPs (\(GRM_{{\varvec{S}}}\)) and \(e\) is the residuals variance. The phenotype and genotype dataset used were sourced from Okeke et al. and included 750 accessions and 76,453 SNP markers after a minor allele frequency filtering threshold of 0.01, below which SNPs were removed3. These historical datasets are from multiple trials conducted at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria, as a part of their genetic gain population and represented clones selected between 1970s through 200783.

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Save and Grow: Cassava: A Guide to Sustainable Production Intensification (Food & Agriculture Organization, 2018).

Dixon, A. G. O. et al. Fast track participatory approach to release of elite cassava genotypes for various uses in Nigeria’s cassava economy. Euphytica 160, 1–13 (2008).

Okeke, U. G., Akdemir, D., Rabbi, I., Kulakow, P. & Jannink, J.-L. Accuracies of univariate and multivariate genomic prediction models in African cassava. Genet. Sel. Evol. 49, 88 (2017).

Hu, W. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor family in cassava. PLoS ONE 10, e0136993 (2015).

Wang, Z., Gerstein, M. & Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63 (2009).

Herrera Campo, B. V., Hyman, G. & Bellotti, A. Threats to cassava production: Known and potential geographic distribution of four key biotic constraints. Food Secur. 3, 329–345 (2011).

Siriwan, W. et al. Surveillance and diagnostics of the emergent Sri Lankan cassava mosaic virus (Fam. Geminiviridae) in Southeast Asia. Virus Res. 285, 197959 (2020).

Vidya, P., Nair, A. G. H., Sreekumar, J., Sheela, M. N. & Mohan, C. Identification of disease resistance genes in cassava using NBS transcriptome profiling. Afr. J. Root Tuber Crops 41, 12–16 (2015).

Rabbi, I. Y. et al. High-resolution mapping of resistance to cassava mosaic geminiviruses in cassava using genotyping-by-sequencing and its implications for breeding. Virus Res. 186, 87–96 (2014).

Wolfe, M. D. et al. Genome-wide association and prediction reveals genetic architecture of cassava mosaic disease resistance and prospects for rapid genetic improvement. Plant Genome https://doi.org/10.3835/plantgenome2015.11.011 (2016).

Kayondo, S. I. et al. Genome-wide association mapping and genomic prediction for CBSD resistance in Manihot esculenta. Sci. Rep. 8, 1549 (2018).

Kawuki, R. S. et al. Alternative approaches for assessing cassava brown streak root necrosis to guide resistance breeding and selection. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1461 (2019).

Amuge, T. et al. A time series transcriptome analysis of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) varieties challenged with Ugandan cassava brown streak virus. Sci. Rep. 7, 9747 (2017).

Maruthi, M. N., Bouvaine, S., Tufan, H. A., Mohammed, I. U. & Hillocks, R. J. Transcriptional response of virus-infected cassava and identification of putative sources of resistance for cassava brown streak disease. PLoS ONE 9, e96642 (2014).

Wilson, M. C. et al. Gene expression atlas for the food security crop cassava. New Phytol. 213, 1632–1641 (2017).

Oshlack, A. & Wakefield, M. J. Transcript length bias in RNA-seq data confounds systems biology. Biol. Direct 4, 14 (2009).

Ma, F. et al. A comparison between whole transcript and 3’ RNA sequencing methods using Kapa and Lexogen library preparation methods. BMC Genom. 20, 9 (2019).

Kremling, K. A. G. et al. Dysregulation of expression correlates with rare-allele burden and fitness loss in maize. Nature 555, 520–523 (2018).

Golan, D., Lander, E. S. & Rosset, S. Measuring missing heritability: Inferring the contribution of common variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E5272–E5281 (2014).

Eveland, A. L., McCarty, D. R. & Koch, K. E. Transcript profiling by 3’-untranslated region sequencing resolves expression of gene families. Plant Physiol. 146, 32–44 (2008).

Lyons, J. B. et al. Current status and impending progress for cassava structural genomics. Plant Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-020-01104-w (2021).

Fernandez-Pozo, N. et al. The sol genomics network (SGN)–from genotype to phenotype to breeding. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D1036–D1041 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Zhang, N. & Portis, A. R. Jr. Mechanism of light regulation of Rubisco: A specific role for the larger Rubisco activase isoform involving reductive activation by thioredoxin-f. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9438–9443 (1999).

Shan, X. et al. The role of Arabidopsis Rubisco activase in jasmonate-induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 155, 751–764 (2011).

Mukiibi, D. R. et al. Resistance of advanced cassava breeding clones to infection by major viruses in Uganda. Crop Prot. 115, 104–112 (2019).

Houngue, J. A. et al. Evaluation of resistance to cassava mosaic disease in selected African cassava cultivars using combined molecular and greenhouse grafting tools. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 105, 47–53 (2019).

Keller, H., Boyer, L. & Abad, P. Disease susceptibility in the Zig-Zag model of host–microbe interactions: Only a consequence of immune suppression?. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 475–479 (2016).

Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009).

Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 (2009).

Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Casagrande, J. T. & Thomas, P. D. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1551–1566 (2013).

Bredeson, J. V. et al. Sequencing wild and cultivated cassava and related species reveals extensive interspecific hybridization and genetic diversity. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 562–570 (2016).

Ogbonna, A. C. et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study, using historical data, identifies conserved genetic architecture of cyanogenic glucoside content in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) root. Plant J. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.15071 (2020).

Jones, J. D. G. & Dangl, J. L. The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 (2006).

Lozano, R. et al. RNA polymerase mapping in plants identifies enhancers enriched in causal variants. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/376640 (2018).

Hudson, W. H. & Ortlund, E. A. The structure, function and evolution of proteins that bind DNA and RNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 749–760 (2014).

Obata, T. et al. Metabolic profiles of six African cultivars of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) highlight bottlenecks of root yield. Plant J. 102, 1202–1219 (2020).

Omondi, J. O., Lazarovitch, N., Rachmilevitch, S., Yermiyahu, U. & Sperling, O. High nitrogen availability limits photosynthesis and compromises carbohydrate allocation to storage in roots of crantz. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1041 (2019).

Alberts, B. et al. Essential Cell Biology (Norton, 2018).

Liu, Q. et al. Genome-wide identification, expression, and functional analysis of the sugar transporter gene family in cassava (Manihot esculenta). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 987 (2018).

Vasconcelos, L. M., Brito, A. C., Carmo, C. D. & Oliveira, E. J. Polymorphism of starch pathway genes in cassava. Genet. Mol. Res. 15, gmr15049082 (2016).

Okeke, U. G., Akdemir, D., Rabbi, I., Kulakow, P. & Jannink, J.-L. Regional heritability mapping provides insights into dry matter content in African white and yellow cassava populations. Plant Genome 11, 1–18 (2018).

López, C. E. et al. Isolation of resistance gene candidates (RGCs) and characterization of an RGC cluster in cassava. Mol. Genet. Genom. 269, 658–671 (2003).

Allie, F., Pierce, E. J., Okoniewski, M. J. & Rey, C. Transcriptional analysis of South African cassava mosaic virus-infected susceptible and tolerant landraces of cassava highlights differences in resistance, basal defense and cell wall associated genes during infection. BMC Genom. 15, 1006 (2014).

Akano, O., Dixon, O., Mba, C., Barrera, E. & Fregene, M. Genetic mapping of a dominant gene conferring resistance to cassava mosaic disease. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105, 521–525 (2002).

Lokko, Y., Danquah, E. & Offei, S. Molecular markers associated with a new source of resistance to the cassava mosaic disease. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 4, 873–881 (2005).

Okogbenin, E. et al. Molecular marker analysis and validation of resistance to cassava mosaic disease in elite cassava genotypes in Nigeria. Crop Breed. Genet. 52, 2576–2586 (2012).

Okogbenin, E. et al. Marker-assisted introgression of resistance to cassava mosaic disease into Latin American germplasm for the genetic improvement of cassava in Africa. Crop Sci. 47, 1895–1904 (2007).

Mohan, C. et al. Mapping new genetic markers associated with CMD resistance in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) using simple sequence repeat markers. J. Agric. Sci. 5, 57 (2013).

van Loon, L. C., Rep, M. & Pieterse, C. M. J. Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 135–162 (2006).

Schmid, M. et al. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 37, 501–506 (2005).

Thoma, S. et al. Tissue-specific expression of a gene encoding a cell wall-localized lipid transfer protein from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 105, 35–45 (1994).

Liu, F. et al. Non-specific lipid transfer proteins in plants: Presenting new advances and an integrated functional analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 5663–5681 (2015).

Boutrot, F., Chantret, N. & Gautier, M.-F. Genome-wide analysis of the rice and Arabidopsis non-specific lipid transfer protein (nsLtp) gene families and identification of wheat nsLtp genes by EST data mining. BMC Genom. 9, 86 (2008).

Carvalho, A. O. & Gomes, V. M. Role of plant lipid transfer proteins in plant cell physiology-a concise review. Peptides 28, 1144–1153 (2007).

Vroemen, C. W. et al. Pattern formation in the Arabidopsis embryo revealed by position-specific lipid transfer protein gene expression. Plant Cell 8, 783–791 (1996).

Blein, J.-P., Coutos-Thévenot, P., Marion, D. & Ponchet, M. From elicitins to lipid-transfer proteins: A new insight in cell signalling involved in plant defence mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 293–296 (2002).

Kawuki, R. S. et al. Eleven years of breeding efforts to combat cassava brown streak disease. Breed. Sci. 66, 560–571 (2016).

Ige, A. D. et al. Conversion and validation of uniplex SNP markers for selection of resistance to cassava mosaic disease in cassava breeding programs. Agronomy 11, 420 (2021).

Fregene, M., Bernal, A., Duque, M., Dixon, A. & Tohme, J. AFLP analysis of African cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) germplasm resistant to the cassava mosaic disease (CMD). Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 678–685 (2000).

Li, K. et al. Proteome characterization of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) somatic embryos, plantlets and tuberous roots. Proteome Sci. 8, 10 (2010).

Prochnik, S. et al. The cassava genome: Current progress, future directions. Trop. Plant Biol. 5, 88–94 (2012).

Wang, W. et al. Cassava genome from a wild ancestor to cultivated varieties. Nat. Commun. 5, 5110 (2014).

Uarrota, V. G. et al. Metabolomics combined with chemometric tools (PCA, HCA, PLS-DA and SVM) for screening cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) roots during postharvest physiological deterioration. Food Chem. 161, 67–78 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. CG gene body DNA methylation changes and evolution of duplicated genes in cassava. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 13729–13734 (2015).

Uarrota, V. G. & Maraschin, M. Metabolomic, enzymatic, and histochemical analyzes of cassava roots during postharvest physiological deterioration. BMC Res. Notes 8, 648 (2015).

Kuon, J.-E. et al. Haplotype-resolved genomes of geminivirus-resistant and geminivirus-susceptible African cassava cultivars. BMC Biol. 17, 75 (2019).

Rosado-Souza, L. et al. Cassava metabolomics and starch quality. Curr. Protoc. Plant Biol. 4, e20102 (2019).

Perez-Fons, L. et al. The metabotyping of an East African cassava diversity panel: A core collection for developing biotic stress tolerance in cassava. PLoS ONE 15, e0242245 (2020).

Ding, Z. et al. Extensive post-transcriptional regulation revealed by transcriptomic and proteomic integrative analysis in cassava under drought. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 3521–3534 (2019).

Yan, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of storage roots in cassava during postharvest physiological deterioration. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-020-01274-3 (2021).

Wan, C. Y. & Wilkins, T. A. A modified hot borate method significantly enhances the yield of high-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Anal. Biochem. 223, 7–12 (1994).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Fernandez-Pozo, N. et al. The tomato expression atlas. Bioinformatics 33, 2397 (2017).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559 (2008).

Yoav Benjamini, Y. H. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Rego, E. C. S. et al. Stable reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression in the Musa acuminate–Pseudocercospora musae interaction. Sci. Rep. 9, 14592 (2019).

Akdemir, D. & Jannink, J.-L. Locally epistatic genomic relationship matrices for genomic association and prediction. Genetics 199, 857–871 (2015).

Website. Akdemir, D. & Okeke, U. G. EMMREML: Fitting Mixed Models with Known Covariance Structures. https://cran.r-project.org/package=EMMREML. R package version 3.1 (2015).

Okechukwu, R. U. & Dixon, A. G. O. Genetic gains from 30 years of cassava breeding in Nigeria for storage root yield and disease resistance in elite cassava genotypes. J. Crop Improv. 22, 181–208 (2008).

Staskawicz, B. J. Genetics of plant–pathogen interactions specifying plant disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 125, 73–76 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Susan McCouch for providing helpful discussion and feedback. Field experiment, sample collection and sequencing were carried out by the National Crops Resources Research Institute, Uganda and dataset was deposited on https://cassavabase.org ftp site (ftp://ftp.cassavabase.org/Cassava3primeRNAseqRawReads/). This work was partially supported by the NEXTGEN Cassava project, through a grant to Cornell University by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant INV‐007637 http://www.gatesfoundation.org) and the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the research: A.C.O., E.W., R.P., G.B., J.L.J., L.M. Performed the research: A.C.O. Contributed to Cassava Expression Atlas: A.C.O., G.B., N.M., A.P. Contributed data: E.W., R.K., L.N. Wrote the paper: A.C.O. Supervised the research: LM. Contributed to the manuscript editing: R.P., G.B., L.M., J.L.J., E.W., N.M., A.P., L.N. All authors reviewed the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogbonna, A.C., Ramu, P., Esuma, W. et al. A population based expression atlas provides insights into disease resistance and other physiological traits in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Sci Rep 11, 23520 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02794-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02794-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.