Abstract

Conflicting evidence was found about the relationship between lipid profiles and R219K polymorphism in adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette exporter A1 (ABCA1) gene. In this study, four meta-analyses were conducted to assess the effect of R219K on lipid levels, including high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides (TG). A total of 125 samples of 87 studies (about 60,262 subjects) were included. The effect of each study was expressed using the standard mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and pooled by meta-analysis in the random-effects model. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted to explore potential heterogeneity sources. The overall pooled effect showed the following results. (1) The R219K was significantly associated with HDLC level (SMD = − 0.25 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.32 to − 0.18, z = − 6.96, P < 0.01, recessive genetic model). People with different genotypes had significantly different HDLC levels under the recessive, codominant and dominant genetic models (all Ps < 0.01). (2) A weak and indeterminate relationship between R219K and TG level was observed (SMD = 0.18 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.06–0.30, z = 3.01, P < 0.01, recessive genetic model). These findings suggested that R219K was associated with HDLC and TG levels, which might implicate a promising clinical application for lipid-related disorders, though the influences of race, health status, BMI, and other heterogeneity sources should be considered when interpreting current findings. The protocol was registered at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021231178).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An optimal blood lipid level is important. Abnormalities in blood lipid levels are causally linked to several common human diseases, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, obesity and stroke1,2,3,4,5,6. The lipid profile generally serves as an initial screening tool for lipid abnormalities and an important predictor of the above diseases. Investigations to explore the sources that contribute to the difference of lipid levels amongst individuals have attracted the interest of clinicians and researchers.

The lipid levels in the blood, which are usually presented by four traditional lipids (i.e. high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDLC; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDLC; total cholesterol, TC; and triglycerides, TG), have high heritability. Approximately 10–15% of the variances amongst individual blood lipid levels can be explained by genetic effects7. Consequently, understanding the genetic architecture and regulation of lipid profiles will help in predicting, monitoring and treating the above human diseases8. To date, many genes which involved in lipid metabolism have been identified to be associated with variations in individual lipid levels9,10.

The ABCA1 is an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) subfamily A transporter. Genetic variants of the ABCA1 gene are generally believed to cause individual differences in lipid levels11,12,13 because of its important role in controlling the circulating lipoprotein levels between cellular and extracellular media14. An arg219-to-lys (R219K, rs2230806) polymorphism in the seventh exon of the ABCA1 gene has been extensively studied, although its biological function remains not fully understood. The association between R219K and lipid levels is often used as an endophenotype of patients and is combined with clinical diagnosis to help identify the causal genetic factors of human diseases, including hypercholesterolaemia15, heart disease16 and CVD13,17. However, those reported correlations remain inconsistent and are ambiguous.

The links observed between the R219K polymorphism and risk of above diseases have resulted in other questions from clinicians and scientists. (1) Do the genotypes of R219K significantly contribute to the difference in human blood lipid levels no matter in patients or general/healthy population? This issue means that individuals born with a favourable genotype have already some advantages in CVD, diabetes, obesity, stroke and other diseases events compared with those born with other genotypes18; (2) the difference in the effect of R219K on lipids level between the general population and patients is due to abnormal levels of certain lipids. Given that the significant difference in the effect between two populations, genetic detection is valuable and promising for the above diseases’ diagnosis, monitoring and strategic therapeutic approach design; (3) the influence of potential modulators on the correlation between R219K and lipid profile should be estimated. The effect of R219K on the level of lipids is still not well defined because every study is evaluated in various cohorts (e.g. race, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), healthy or with all kind of diseases and others). Previous meta-analyses19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 are mainly emphasised the genetic variants of R219K and the risk of diseases rather than the consistency of their relationship amongst the general population. Furthermore, results from new studies remain inconsistent with those based on previous meta-analyses. The difference of the correlations between R219K and lipid profile in patients and general population is not extensively discussed and estimated quantitatively.

Four updated meta-analyses of the correlations between R219K polymorphism and HDLC, LDLC, TC and TG levels are conducted to reach conclusive answers. This work aims to: (1) investigate the relationship between R219K polymorphism and individual lipid levels within both the general population and patients with common diseases; (2) assess the consistency of this relationship amongst different populations; and (3) estimate the influence of other external factors on this correlation.

Methods

Search strategy and criteria

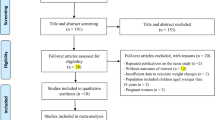

This systematic review protocol was submitted for registration to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero) on 5 February 2021 and published on 8 March 2021 (Registration ID: CRD42021231178). Two authors (Shi Z and Tian Y) searched for studies published before 31 March 2021 and extracted useful data from the databases of BIOSIS, CENTRAL and Clinical trials, Derwent Innovations Index, EMBASE, InspecR, ISI Web of Science, KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, PubMed, SciELO Citation Index and Scopus for papers in English and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases for papers in Chinese. The full search strategy and literature terms used for searching the above databases are described in Fig. 1.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the mean lipids and standard deviations (SD) and/or standard errors (SE) were available for each group according to R219K genotypes; (2) at least one of the four variables (i.e. HDLC, LDLC, TC and TG) was available; (3) the frequency of R219K genotype and the deviation of genotypes from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was also described; and (4) other related information that can be used to calculate the effect size of R219K on the four lipid variables or the required data could be collected from other publications. Similarly, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplication and meeting summary; (2) no relevance of the R219K polymorphism on the ABCA1 gene; and (3) the original document was unavailable.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Information extracted from the eligible literature included the following: (1) name of the first-author, time of publication and number of samples; (2) health status, ethnicity, BMI and mean age of subjects and sex (proportion of females in each sample); (3) mean lipid levels, standard deviation and/or standard error for different groups according to R219K genotype; and (4) other format data that could be used to calculate the effect size value. Required data were extracted and formatted as described in the online supplementary material (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The quality of all articles was evaluated by two authors (Shi and Tian) in accordance with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) assessment scale35. Comparing the frequencies of studies categorized by the median NOS score of included studies, two authors’ consensus assessments had high inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.81, P < 0.01). The deviation from the HWE for each sample’s distribution of R219K genotypes was assessed using the HardyWeinberg package36 and used as one of important index of NOS.

Statistical analysis

We conducted meta-analysis by using two R programs of meta and metaphor37,38. The effect size of R219K on lipid levels in each study was presented in the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) format since various measurements and methods were involved with different scales39. The random-effects model, which considered within- and between-study variances40, was adopted to estimate the pooled effect size of all studies because of the potential sources of heterogenous (e.g. different measurements of lipid levels, race, health status of subjects, age and NOS score) amongst eligible studies. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 statistics41. Regarding R219K polymorphism’s inconsistent genetic structure in different population and diverse genetic models reports, three codominant models (RR vs. KK, RR vs. RK and RK vs. KK), dominant (RR + RK vs. KK), recessive (RR vs. RK + KK) and codominant (RK vs. RR + KK) models were used to estimate this variant’s effect size on human lipid levels.

The sources of heterogeneity were explored and their influences were assessed by (1) pooling the effect of each subgroup defined by categorical variables (e.g. race and health status) and (2) comparing the effects of the subgroups as recommended by Borenstein and Higgins42 and (3) estimating the influence of interested potential moderators on the effect of R219K. A meta-regression analysis was performed using the mixed-effects model (random-effects model within subgroups, fixed-effects model amongst subgroups)43. The differences of the effect of R219K on lipid profiles between groups were tested using the method of DerSimonian-Laird estimator for tau244. Simultaneously, the omnibus test (QM) and goodness of fit test (QG) were carried out to access the influence of all target moderators on the effect and calculate whether other unknown moderators also contributed to the variance of effect of R219K on lipid profiles.

Some studies with extreme effect sizes (outliers) might cause concerns and distort our pooled effect45. So, the influence analyses were performed to detect and remove outliers amongst all eligible studies by using the R function of influence.analysis. The publication bias was examined using the Begg’s rank correlation46 and Egger’s weighted regression tests47, visualised by funnel plots with based on “trim and fill” test48. The sensitivity of the results was examined using the leave1out function. Permutation tests, which assumed normality of the observed effects and relied on the asymptotic behaviour of the test statistics, were also performed using the permutest function with 1000 iterations to control the Type I error rate. All significance tests were two-tailed, and the significance threshold was set to < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies and samples

A total of 87 studies met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of literature search. As described in the Supplementary File, 125 samples and 60,262 subjects were involved. Approximately 45.26% of the subjects were women. About 45.71% (samples = 84, n = 27,548) and 50.35% (samples = 37, n = 30,340) of the subjects were Asians and Caucasians, respectively. One sample (n = 128) was from Africa49, and three samples (3.94%, n = 2246) were mixed population50,51. According to the participants’ clinical information, 52 patient samples (28.04%, n = 16,900), 47 random samples (53.94%, n = 32,504; including 21 general population and 22 control samples of case–control studies) and mixed samples (i.e. including patients and controls; 18.02%, n = 10,858) were obtained from all studies. More than 12 kinds of diseases, including coronary artery disease (samples = 13), coronary artery disease (samples = 8), dyslipidaemia (samples = 7), type 2 diabetes (samples = 6), overweight (samples = 6), Alzheimer’s disease (samples = 2), acute myocardial infarction (samples = 2), Parkinson’s disease, cerebral infarction, frontotemporal dementia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, ischemic heart disease and preeclampsia, were included in these eligible studies. Amongst 125 samples, the distribution of R219K genotypes in seven samples13,52,53,54,55,56,57 was reported to significantly deviate from the HWE, and another seven samples (Chen et al.58; hypercholesterolemic group of Katerina et al.52; Liu et al.59; Wang et al.60; PD patients of Ya and Lu61; and female group of Zhao et al.62; Supplementary File) in which the distribution of R219K genotypes were also not in HWE assessed with R package of HardyWeinberg36.

Relationship between R219K and HDLC levels

Overall pooled effect of R219K on the HDLC level

Table 1 shows that regardless of model (i.e. in three codominant models, dominant and recessive genetic models), the R219K polymorphism had a solid effect on the human HDLC level (all Ps < 0.01). This consistent result was observed after the detection and removal of outliers (all Ps < 0.01). For instance, under the recessive genetic model, the homozygous R allele had a significantly lower HDLC level than the K allele carrier (SMD = − 0.25 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.32 to − 0.18, z = − 6.96, P < 0.01), as observed using the random-effects model. Extreme heterogeneity (I2 = 93.31%, Q = 1763.65, df = 118, P < 0.01) was also observed amongst eligible studies. A consistent relationship was observed after running 1000 iterations for the approximate permutation test (Ppermutation = 0.01). Amongst the eligible studies, six samples (EI-Aziz et al.17, data 1 of Çoban et al.63, two samples of Sun et al.64, and Ya et al.’s61 AD and PD samples) were identified as outliers with low-quality data and extreme effect size (Supplementary Fig. S1) and ruled out in the following analyses. The RR genotype population still showed a significantly lower HDLC level (SMD = − 0.13 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.17 to − 0.08, z = − 6.11, P < 0.01, P mutation < 0.01; and I2 = 80.42%, Q = 572.04, df = 112, P < 0.01) than K allele carriers in the random-effects model.

Effect of R219K on the HDLC levels of Asian and Caucasian subgroups

Hierarchical meta-analyses were performed to estimate the influence of race on the R219K effect (Supplementary Table S3). Consistent with the results of total samples, significant effects of R219K on the human HDLC level in the Asian population (all Ps < 0.01) with extremely heterogeneity (all I2 > 56% and Ps < 0.01) were observed under codominant, dominant and recessive genetic models. Under difference genetic models, Caucasian populations did not show a consistent result (Supplementary Table S3). The difference of the R219K effects on the HDLC level between Asian and Caucasian populations was estimated, showing a significant difference under the codominant 2 model (RR vs. KK, SMD = − 0.23 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.37 to − 0.21 vs. SMD = − 0.05 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.18 to 0.08; and Q = 9.71, df = 1, P < 0.01) and a weak difference under the recessive model (RR vs. RK + KK, SMD = − 0.17 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.22 to − 0.12 vs. SMD = − 0.08 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.16 to 0.01; and Q = 3.58, df = 1, P = 0.06). No significant difference was observed under other genetic models (Supplementary Table S3).

Effect of R219K on the HDLC levels in different health status subgroups

Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Fig. S2 show the difference of effect of R219K on the HDLC level by considering participants’ clinical information. Under two codominant, dominant and recessive models, a significant correlation was observed between R219K and HDLC level regardless of patient group (all Ps < 0.02), random population (general, all Ps < 0.02) and mixed population (all Ps < 0.01). For instance, under the recessive genetic model, the average HDLC level in the RR genotype group was significantly lower than that in K allele carriers within patient samples (SMD = − 0.15 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.23 to − 0.06, z = − 3.46, P < 0.01), and the same trend was also observed in random and mixed populations (random population: SMD = − 0.11 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.17 to − 0.05, z = − 3.60, P < 0.01; mixed population: SMD = − 0.14 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.24 to − 0.05, z = − 2.98, P < 0.01). Additionally, under the codominant 1 (RK vs. KK) and dominant (RR + RK vs. KK) models, the effect of R219K was significantly different in accordance with the clinical conditions of different participants (codominant 1 model: Q = 8.39, df = 2, P = 0.02; dominant model: Q = 6.81, df = 2, P = 0.03; Supplementary Table S3).

Sources of heterogeneity

Moderators, including categorical (e.g. race and health status) and numerical (e.g. publication time, sample size, BMI, sex, age and NOS score) variables, which might contribute to such observed extreme heterogeneity, were analysed using the meta-regression analysis. The influence of each variable on the effect of R219K was estimated. Table 2 describes that the participants’ health status showed an obvious influence on the effect of R219K (Q = 4.91, df = 2, P = 0.08). Comparing to mix health status participants, the effect of R219K in patients was higher than that of general population (patients: β = 0.22, z = 1.63, P = 0.10; random samples: β = − 0.01, z = − 0.10, P = 0.92) under the recessive genetic model. Additionally, the sex of participants (i.e. proportion of females in each sample) showed a significant influence on the effect of R219K (β = 0.38, z = 2.17, P = 0.01). Race did not influence the R219K effect, although different relationships were observed in different subgroups (Supplementary Table S3).

Publication bias analysis

Amongst five genetic models, the methods of Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression detected significant publication selection bias in this meta-analysis. For instance, under the recessive model, both of methods suggested significant publication bias consistently (Begg’s test: tau = − 0.28, P < 0.01; Egger’s test: z = − 4.36, P < 0.01). The funnel plot also showed a considerable asymmetry distribution amongst the included studies (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, the trim-and-fill test indicated approximately 34 studies on the left side of the mean effect missing, and a consistent overall effect (SMDadj = − 0.42 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.50 to − 0.34; z = − 10.33, P < 0.01) was observed after adjustment. The sensitivity analysis indicated that the effect sizes of removing any single study did not deviate from the overall effect.

Meta-analysis for the genetic variant R219K and LDLC levels

The pooled effect of the genetic variant R219K on LDLC levels was estimated using 74 eligible studies (samples = 104) including 39,323 participants. Under six genetic models, the relationship between R219K and individual’s LDLC level was estimated using the meta-analysis. Under the dominant model, R allele carriers (i.e. with RR + RK genotypes) showed a significantly lower LDLC level than the KK genotype group (SMD = − 0.22 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.39 to − 0.06, z = − 2.63, P < 0.01). Under codominant (RK vs. KK genotype) and over dominant (RK vs. RR + KK genotypes) models, a weak correlation between R219K and LDLC level was also detected (codominant: SMD = − 0.08 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.16 to − 0.03, z = − 2.03, P = 0.04; over dominant: SMD = − 0.05 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.09 to − 0.01, z = − 2.12, P = 0.03). However, no significant correlation was observed under these three genetic models (all Ps > 0.05, Table 1) after removing three studies with outliers63,65,66 (Supplementary Fig. S4).

For potential modulators (e.g. race, BMI, health status, publication time, sample size, gender, age and NOS score), no significant modulation on the effect of R219K was found using hierarchical and meta-regression analyses. The Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression tests showed no consistent publication bias in all genetic models.

Meta-analysis for the genetic variant R219K and TC levels

The effect size of the genetic variant R219K on TC levels was pooled from 69 studies (samples = 106, n = 35,885). The meta-analysis showed no significant difference in the TC levels of the RR genotype population and K allele carriers in the random model and a significant heterogeneity amongst all studies. After removing the five outliers (Çoban et al.63 data1; Katzov et al.67 and Ya61 data1, 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. S5) detected by the meta and metafor packages, a consistent result was obtained. Hierarchical and meta-regression analyses, which were used to explore heterogeneity amongst samples, did not observe any moderator impacted the effect of R219K. Furthermore, no significant publication bias was found amongst the current selected studies.

Meta-analysis for the genetic variant R219K and TG levels

A total of 76 eligible studies (samples = 103, n = 38,304) were collected in this study to explore the relationship between the R219K polymorphism and individual TG levels. Under the recessive model, the RR genotype population had significantly higher TG level than K allele carriers (SMD = 0.18 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.06 to 0.30, z = 3.01, P < 0.01), and I 2 = 96.38% (Q = 2,816, df = 106, P < 0.01) for the heterogeneity test. After removing six outliers (Çoban63 data 1 and data 2, Delgado-Lista68, Sun64 data1 and data 2, Ya61 data1; Supplementary Fig. S6), the significant effect of R219K was also observed in two codominant (RK vs. KK: SMD = 0.18 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.09 to 0.26, z = 4.01, P < 0.01; RR vs. KK: SMD = 0.16 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.08 to 0.25, z = 3.67, P < 0.01), dominant (RR + RK vs. KK: SMD = 0.17 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.07 to 0.27, z = 3.24, P < 0.01) and recessive (RR vs. KK + RK: SMD = 0.07 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.01 to 0.12, z = 2.56, P = 0.01) models.

The influences of ethnicity and health status of participants on the effect of R219K were investigated, and a complex relationship was observed. Under four genetic models (i.e. RK vs. KK; RR vs. KK; RR + RK vs. KK; and RR vs. RK + KK), R219K had a significant effect on the TG levels (all Ps < 0.01, Supplementary Table S4) within Asian populations. For instance, Asians with the RR genotype had a significantly lower TG level than those with K allele carriers (RR vs. RK + KK: SMD = 0.08 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.02 to 0.13, z = 2.65, P < 0.01). Only a weak effect was observed within the Caucasian population (RR vs. RK + KK: SMD = 0.02 mmol/L, 95%CI − 0.12 to 0.16, z = 0.27, P = 0.78; Supplementary Fig. S7). Unfortunately, the R219K effects between two populations did not reach a significant difference. Considering the health status of participants (i.e. patients, general population and mixed population), significant effects of R219K on the TG level were observed under two codominant models (RK vs. KK and RR vs. KK; all Ps < 0.05) in all three subgroups. No significant effect was detected under three genetic models (RK vs. RR; RR vs. RK + KK; and RK vs. RR + KK; all Ps > 0.05), and an inconsistent result was observed under the dominant model (i.e. RR + RK vs. KK; Supplementary Table S4). In addition, the influence of the sex (i.e. the proportion of females in each sample) on the effect of R219K was observed. The meta-regression analysis revealed that the higher the proportion of females in samples, the higher the effect was detected (β = − 1.57, 95%CI − 2.20 to − 0.93, z = − 4.5, P < 0.01). The significant influence of NOS score on relationship between R219K and TG level under recessive model (β = 0.27, 95%CI 0.03 to 0.52, z = 2.17, P = 0.03; Supplementary Table S5) also suggested that the studies quality should be considered. No significant publication bias was found using the Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression methods. The sensitivity analysis showed that effect sizes did not change remarkably after removing any single study.

Discussion

Given the importance of ABCA1 in the formation of nascent HDLC69,70,71 and its role in the reverse cholesterol transportation72, the relationship between the genetic variant R219K and serum lipid levels (i.e. HDLC, LDLC, TG and TC), and the risk of common human diseases (e.g. CVD23,73, diabetes74 and obesity49) has been extensively investigated. Thus, this polymorphism has been observed as a promising prognostic and predictive biomarker of these diseases for susceptible individuals23. However, such relationship between this polymorphism and lipid levels still presents some controversies. Here, we conducted four updated meta-analyses based on current studies and observed the consistent significant effect of R219K on the level of HDLC under codominant, dominant and recessive genetic models. At the same time, the weak correlation of R219K with LDLC and TG levels was detected.

HDLC is the well-behaved “good cholesterol” because it removes harmful “bad cholesterol” from the body, and increasing evidence showed that the K allele of R219K is positively associated with elevated HDLC level and lower risks of common human diseases (e.g. CVD, diabetes and stroke)75. On the basis of the data of more than 80 studies, this study confirmed the significant effect of R219K on the level of HDLC under the codominant, dominant and recessive genetic models (all Ps < 0.01) even after the removal of outliers and the correction of permutation test with 1000 iterations. This finding was consistent with previous reports28,29. However, the effect of R219K on the levels of TG and LDLC seemed somewhat unclear. For the TG level, R219K showed a consistent effect only in the recessive model (i.e. RR vs. RK + KK; Table 1). Previous studies63,76,77 reported that the RR genotype had a higher level of TG than K carriers (SMD = 0.18 mmol/L, 95%CI 0.06 to 0.30, z = 3.01, P < 0.01). For the LDLC level, some studies65,78 and meta-analyses28 reported the association between R219K and LDLC level, which disappeared when studies with the outliers were removed. Such results demonstrated the value of R219K in the clinical application of the above mentioned diseases’ diagnosis, monitoring and strategic therapeutic approach design75, but other potential elements, such as the influence of outliers, race, gender, and age, should be treated with caution.

The fluctuation of the effect of R219K on lipid levels for each study is becoming another more attractive issue. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression tests indicated that besides the influence of some extreme effect sizes, other factors (including race, gender, age and health status of participants) should be considered in this study. Firstly, populations with different conditions (i.e. patient, random and mixed groups) had significantly different effects of R219K. For instance, significantly different effects of R219K were observed on the HDLC level in groups with different health status (patients: SMD = − 0.15 mmol/L; general population: SMD = − 0.16 mmol/L; mix population: SMD = − 0.49 mmol/L; Q = 0.07, df = 2, P = 0.03; Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Fig. S2) in the dominant genetic model. Secondly, as previous studies79,80 mentioned, racial/ethnic difference was observed. Compared with those of Caucasian populations, the effect of R219K on the HDLC and TG levels of Asian populations showed more significance and consistency. For the TG level, the effect of R219K was observed under three genetic models (all Ps < 0.01, Supplementary Table S4) in the Asian population only. Furthermore, the influence of sex on the effects of R219K on the levels of HDLC and TG was determined using the meta-regression test. Results showed that samples with different proportions of female participants had varying effects of R219K on HDLC and TG levels (Table 2, Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Fig. S7). These variables might be the reason for the inconsistency on the relationship between R219K and lipid profiles and for the sources of the extreme heterogeneity observed in this study.

The present study had several strengths. (i) It used a robust, systematic and transparent approach in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook and the PRISMA statement. Compared with previous meta-analyses, this study explored the heterogeneity sources by using larger and more comprehensive samples (samples = 22, n = 21,966 in Ma et al.29; samples = 62, n = 48,452 in Lu et al.28, and only type 2 diabetes studies were considered in Jung et al.22). (ii) The metafor package was used for the detection and removal of outliers from total studies to minimise their influence, which usually had a decreased quality and extreme effect size, and obtain a robust pooled effect. The obvious influence of the study’s quality (i.e. NOS score) on the findings (Tables 1 and S5) also demonstrated the necessity of outlier analysis. (iii) All genetic models were introduced in this study. The genetic association study in practice assumed a specific genetic model, such as dominant or recessive, but conclusions might be sensitive to this assumption81. In this study, Table 1 shows the effects of R219K on lipid profiles under six genetic models and demonstrates the sensitivity of this effect.

The limitations of this review must also be mentioned. Firstly, a systemic meta-analysis should collect as much literature as possible, even unpublished studies. However, most of these eligible studies were in English or Chinese. Publication bias analyses also suggested the influence of missing publication studies because the reporting bias82 should be considered (e.g. Supplementary Fig. S3). It is possible that such factor can affect the validity and generalization of our findings about the relationship between R219K and HDLC, LDLC, Cholesterol and TG. Secondly, the random-effects model was predominantly adopted to address the extremely significant heterogeneity amongst the total samples. Hierarchical and regression meta-analyses were also performed to explore the source of heterogeneity, but the source of most of the variances in the effect remained unknown. Thirdly, the health status of the subjects was introduced as a categorical variable to explore its influence on R219K effect, and all patients with six kinds of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and other diseases were classified into one group. However, this “unified” approach might have caused sample heterogeneity in this study. Given sufficient eligible studies for each disease, a network meta-analysis should be performed to determine the comparative effects of all included diseases83.

Conclusion

The present meta-analyses confirmed the effect of R219K in the ABCA1 gene on the level of lipids. Individuals with different genotypes have different levels of lipids (HDLC and TG), which may result in different risks of human diseases. The influences of ethnicity and health status on pooled effects must be considered when interpreting current findings and/or accepting the recommendation for R219K clinical applications in the future.

Data availability

Data used for this study are available from the authors of each included study upon reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its Online Resources.

References

Upadhyay, R. K. Emerging risk biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases and disorders. J. Lipids 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/971453 (2015).

Krauss, R. M. Lipids and lipoproteins in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27, 1496–1504. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.6.1496 (2004).

Pirillo, A., Casula, M., Olmastroni, E., Norata, G. D. & Catapano, A. L. Global epidemiology of dyslipidaemias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00541-4 (2021).

Park, J.-B. et al. Mildly abnormal lipid levels, but not high lipid variability, are associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in “statin-naive” young population a nationwide cohort study. Circ. Res. 126, 824–835. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315705 (2020).

Wu, J., Wang, A., Li, X., Wu, S. & Zhao, X. Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels on the risk of asymptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis: A result from the APAC study. Sci. Rep. 6, 37410. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37410 (2016).

Washirasaksiri, C. et al. Increasing glycaemia is associated with a significant decline in HDL cholesterol in women with prediabetes in two national populations. Sci. Rep. 11, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91075-9 (2021).

Pilia, G. et al. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PLoS Genet. 2, e132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132 (2006).

Tabassum, R. et al. Genetic architecture of human plasma lipidome and its link to cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 10, 4329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11954-8 (2019).

Helgadottir, A. et al. Variants with large effects on blood lipids and the role of cholesterol and triglycerides in coronary disease. Nat. Genet. 48, 634–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3561 (2016).

Waterworth, D. M. et al. Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 2264–2276. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201020 (2010).

Niemsiri, V. et al. Contribution of ABCA1 genetic variation to plasma lipid levels in non-Hispanic White Americans. Circulation 136, A21122–A21122 (2017).

Sameem, M., Rani, A. & Arshad, M. Association of rs146292819 polymorphism in ABCA1 gene with the risk of coronary artery disease in pakistani population. Biochem. Genet. 57, 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-019-09915-3 (2019).

Clee, S. M. et al. Common genetic variation in ABCA1 is associated with altered lipoprotein levels and a modified risk for coronary artery disease. Circulation 103, 1198–1205. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1198 (2001).

Phillips, M. C. Is ABCA1 a lipid transfer protein?. J. Lipid Res. 59, 749–763. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R082313 (2018).

Bertolini, S. et al. Genetic polymorphisms affecting the phenotypic expression of familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 174, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.037 (2004).

Frikke-Schmidt, R., Nordestgaard, B. G., Jensen, G. B., Steffensen, R. & Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. Genetic variation in ABCA1 predicts ischemic heart disease in the general population. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153858 (2008).

Abd El-Aziz, T. A., Mohamed, R. H. & Hagrass, H. A. Increased risk of premature coronary artery disease in Egyptians with ABCA1 (R219K), CETP (TaqIB), and LCAT (4886C/T) genes polymorphism. J. Clin. Lipidol. 8, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2014.06.001 (2014).

Kolovou, V. et al. Effect of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) gene polymorphisms on plasma lipid variables and common demographic parameters in Greek nurses. Open cardiovasc. Med. J. 10, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874192401610010233 (2016).

Hou, R. et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism and ischemic stroke risk in the Chinese population: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 336, 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.006 (2014).

Jiang, M. et al. Meta-analysis on association between the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene (ABCA1) and Alzheimer’s disease. Gene 510, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.009 (2012).

Jiang, Z., Zhou, R., Xu, C., Feng, G. & Zhou, Y. Genetic variation of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 and susceptibility to coronary heart disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 103, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.01.005 (2011).

Jung, D., Cao, S., Liu, M. & Park, S. A meta-analysis of the associations between the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1 R219K (rs2230806) polymorphism and the risk of type 2 diabetes in Asians. Horm. Metab. Res. 50, 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0583-0201 (2018).

Karimian, M. et al. Common gene polymorphism in ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 and coronary artery disease: A genetic association study and a structural analysis. J. Cell Biochem. 121, 3345–3357. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.29606 (2020).

Li, J., Wen, M., Zhang, Z., Qiu, Z. & Sun, Y. The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily a member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population. Open Med. 15, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2020-0039 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Quantitative assessment of the effect of ABCA1 R219K polymorphism on the risk of coronary heart disease. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 1809–1813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-011-0922-z (2012).

Li, Y. Y. et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism and coronary artery disease in Chinese population: A meta-analysis of 5,388 participants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 11031–11039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-012-2006-0 (2012).

Liu, N. et al. The R219K polymorphism on ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene is associated with coronary heart disease risk in Asia population: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 71, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-014-0161-8 (2015).

Lu, Z. et al. Associations of the ABCA1 gene polymorphisms with plasma lipid levels: A meta-analysis. Medicine 97, e13521. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013521 (2018).

Ma, X. Y., Liu, J. P. & Song, Z. Y. Associations of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism with HDL-C level and coronary artery disease risk: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 215, 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.008 (2011).

Wagschal, A. et al. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs regulating cholesterol and triglyceride homeostasis. Nat. Med. 21, 1290–1297. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3980 (2015).

Wang, X. F. et al. Quantitative assessment of the effect of ABCA1 gene polymorphism on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 779–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-012-2115-9 (2013).

Weissglas-Volkov, D. et al. Genomic study in Mexicans identifies a new locus for triglycerides and refines European lipid loci. J. Med. Genet. 50, 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101461 (2013).

Willer, C. J. et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 40, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.76 (2008).

Yin, Y. W. et al. Influence of ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 R219K and M883I polymorphisms on development of atherosclerosis: A meta-analysis of 58 studies. PLoS ONE 9, e86480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086480 (2014).

Wells, G. et al. In Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics.

Graffelman, J. Exploring diallelic genetic markers: The Hardy Weinberg package. J. Stat. Softw. 64(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v064.i03 (2015).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03 (2010).

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 22, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 (2019).

Nagendrababu, V. et al. Glossary for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. Endod. J. 53, 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13217 (2020).

Cuijpers, P. Meta-analyses in Mental Health Research. A Practical Guide (Pim Cuijpers Uitgeverij, 2016).

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 (2002).

Borenstein, M. & Higgins, J. P. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev. Sci. 14, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0377-7 (2013).

Harrer, M., GCuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A. & Ebert, D. D. Doing Meta-Analysis in R: A Hand-on Guide. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2551803 (2019).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp. Clin. Trials 45, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002 (2015).

Viechtbauer, W. & Cheung, M. W. L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11 (2010).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1088–1101 (1994).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 (1997).

Duval, S. The trim and fill method. Publ. Bias Meta-anal. Prev. Assess. Adjust. 127–144 (2005).

Fawzy, M. S. et al. Functional and structural impact of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K and I883M gene polymorphisms in obese children and adolescents. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 19, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-015-0150-7 (2015).

Benton, J. L. et al. Associations between two common polymorphisms in the ABCA1 gene and subclinical atherosclerosis: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 193, 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.024 (2007).

Srinivasan, S. R., Li, S., Chen, W., Boerwinkle, E. & Berenson, G. S. R219K polymorphism of the ABCA1 gene and its modulation of the variations in serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides related to age and adiposity in white versus black young adults. The Bogalusa heart study. Metabolism 52, 930–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00076-3 (2003).

Katerina, H. et al. Interaction of common sequence variants and selected risk factors in determination of HDL cholesterol levels. Clin. Biochem. 43, 754–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.04.001 (2010).

Manresa, J. M. et al. Relationship of classical and non-classical risk factors with genetic variants relevant to coronary heart disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 13, 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hjr.0000224484.80349.3f (2006).

Mao, Y. et al. Study on the association between R219K polymorphism of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene and coronary heart disease in Uygur and Han. West China Med. J. https://doi.org/10.7507/1002-0179.20130488 (2013).

Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Xu, X., Chen, Y. & Zhao, L. Association between R219K polymorphism of ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 gene in Xinjiang Uygur population and coronary heart disease. Xin Xue Guan Kang Fu Yi Xue Za Zhi 18, 35–39 (2009).

Lu, Z. et al. Effects of ABCA1 gene polymorphisms on risk factors, susceptibility and severity of coronary artery disease. Postgrad. Med. J. 96, 666–673. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-136917 (2020).

Teixeira, M. D., Tureck, L. V., Nascimento, G. A. d., Souza, R. L. R. d. & Furtado-Alle, L. Is it possible ABC transporters genetic variants influence the outcomes of a weight-loss diet in obese women? Genet. Mol. Biol. 43, e20190326. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2019-0326 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Association of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism with atrial fibrillation. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao J. South. Med. Univ. 29, 494–496 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Study of correlations of ABCA1 R219K gene polymorphism with coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Chin. J. Diabetes 16, 104–106 (2008).

Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, X. & Zhang, X. Association between Kazakh adenosine triphosphate binding cassette transporter A1 gene R219K polymorphism and blood lipids. Shanxi Med. J. 45, 3 (2016).

Ya, L. & Lu, Z. Differences in ABCA1 R219K polymorphisms and serum indexes in Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases in Northern China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 23, 4591-4600.https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.903636 (2017).

Zhao, S. et al. Relationship between ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 R219K genetic variation and blood lipids. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 84, 1421–1425 (2004).

Çoban, N. et al. Gender specific association of ABCA1 gene R219K variant in coronary disease risk through interactions with serum triglyceride elevation in Turkish adults. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 14, 18-25. https://doi.org/10.5152/akd.2013.234 (2014).

Sun, M. et al. Distributional characteristics of adenosine triphosphate binding cassette transport protein A1 gene R219K polymorphism and association with blood lipid level in healthy Han and Uygur population in Xinjiang. J. Chin. Pract. Diagn. Therapy 25 (2011).

Abellan, R. et al. Association of selected ABC gene family single nucleotide polymorphisms with postprandial lipoproteins: Results from the population-based Hortega study. Atherosclerosis 211, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.030 (2010).

Haghvirdizadeh, P. et al. Association of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes mellitus among Malaysians. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 289846. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/289846 (2015).

Katzov, H. et al. Quantitative trait loci in ABCA1 modify cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β 1–42 and plasma apolipoprotein levels. J. Hum. Genet. 51, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-005-0341-x (2006).

Delgado-Lista, J. et al. ABCA1 gene variants regulate postprandial lipid metabolism in healthy men. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1051–1057. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.109.202580 (2010).

Krimbou, L. et al. Molecular interactions between apoE and ABCA1: Impact on apoE lipidation. J. Lipid Res. 45, 839–848. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M300418-JLR200 (2004).

Marcil, M. et al. Mutations in the ABC1 gene in familial HDL deficiency with defective cholesterol efflux. Lancet 354, 1341–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07026-9 (1999).

Ishigami, M. et al. Temporary sequestration of cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine within extracellular domains of ABCA1 during nascent HDL generation. Sci. Rep. 8, 6170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24428-6 (2018).

Miller, M., Rhyne, J., Hamlette, S., Birnbaum, J. & Rodriguez, A. Genetics of HDL regulation in humans. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 14, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041433-200306000-00007 (2003).

Akao, H. et al. ABCA1 gene variation and heart disease risk reduction in the elderly during pravastatin treatment. Atherosclerosis 235, 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.030 (2014).

Cai, R. et al. Effects of ABCA1 R219K polymorphism and serum lipid profiles on mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00257 (2017).

Jacobo-Albavera, L., Dominguez-Perez, M., Medina-Leyte, D. J., Gonzalez-Garrido, A. & Villarreal-Molina, T. The role of the ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) in human disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041593 (2021).

Genvigir, F. D. et al. Effects of ABCA1 SNPs, including the C-105T novel variant, on serum lipids of Brazilian individuals. Clin. Chim. Acta 389, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2007.11.029 (2008).

Liu, H. et al. Effects of R219K polymorphism of ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 gene on serum lipids ratios induced by a high-carbohydrate and low-fat diet in healthy youth. Biol. Res. 47, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/0717-6287-47-4 (2014).

Marvaki, A. et al. Impact of 3 common ABCA1 gene polymorphisms on optimal vs non-optimal lipid profile in Greek young nurses. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 8, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874192401408010083 (2014).

Frank, A. T. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in dyslipidemia patterns. Circulation 129, 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005757 (2014).

Pu, J. et al. Dyslipidemia in special ethnic populations. Cardiol. Clin. 33, 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2015.01.005 (2015).

Attia, J., Thakkinstian, A. & D’Este, C. Meta-analyses of molecular association studies: Methodologic lessons for genetic epidemiology. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 56, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00011-8 (2003).

Higgins, J., Altman, D. & Sterne, J. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1. 0 (updated March 2011) (eds Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S.) Available from handbook. cochrane.org (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011).

Tonin, F. S., Rotta, I., Mendes, A. M. & Pontarolo, R. Network meta-analysis: A technique to gather evidence from direct and indirect comparisons. Pharm. Pract. 15, 943. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2017.01.943 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors of the articles included in this study and the staff at the Institute of Health & Population for logistical support of this review.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81473297; No. 81760080; and No. 31960149) and “Zhiyuan Talent Program” of Inner Mongolia Medical University (No. ZY0120024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.Z. and C.Y.A. conceived and designed the study; Z.Y.S., Y.J.T. and X.X.H. collected the data; K.J.Z. and Y.F.W. analyzed the data; K.J.Z., J.L.L. and Q.L.C. interpreted the results and edited the article. Z.Z. and Y.W revised the article. All authors had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Tian, Y., Zhao, Z. et al. Association between the ABCA1 (R219K) polymorphism and lipid profiles: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 21718 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00961-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00961-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.