Abstract

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play an important role in kimchi fermentation by metabolizing raw materials into diverse metabolites. Bacterial adaptation is therefore a crucial element of fermentation. In this study, we investigated the transcriptional changes of Lactobacillus plantarum under acidic conditions to evaluate the elements of bacterial adaptation critical for fermentation. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have shown that transport function is primarily affected by acidic conditions. Five of the 13 significantly down-regulated genes and 7 of the 25 significantly up-regulated genes were found to have transport-related functions. We quantified the intracellular leucine content of bacteria grown at different pH ranges, determining that optimal bacterial leucine transport could be controlled by acidity during fermentation. Inhibition of L. plantarum growth was investigated and compared with other LAB at a pH range of 6.2–5.0. Interestingly, valinomycin inhibited L. plantarum growth from pH 6.2 to 5.0. This showed that L. plantarum had a wider range of transport functions than other LAB. These results suggested that L. plantarum had robust transport functions, and that this was the crucial factor for bacterial adaptation during fermentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kimchi is a well-known fermented food mainly comprising salted cabbage, radish, ginger, garlic, and red pepper powder. Kimchi and fermented foods have been reported to have beneficial effects on health, and this is believed to be associated with probiotic lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and postbiotic fermented metabolites1,2,3,4.

A sour taste is one of the most characteristic features of kimchi, and is mainly caused by the production of organic acid during fermentation. The pH at the initial stage is around 6 and decreases to pH 4 at the fourth week of fermentation5. Lactic acid is most abundant organic acid involved in kimchi fermentation, and is produced by hetero- and homo-fermentative LAB1. The lactic acid content and composition could be affected by the pasteurization temperature and storage conditions6,7. The lactic acid content was approximately 50–70% of the total organic acid, and had a higher concentration when kimchi was stored at 10 °C than at 4 °C7.

Acidification is an important aspect of kimchi fermentation, as it prevents the growth of undesired bacteria. However, it also affects the dynamics of LAB during kimchi fermentation, due to the difference in acid tolerance among the LAB groups.

The genera Leuconostoc, Weissella, and Lactobacillus are the major groups of LAB involved in kimchi fermentation1,5,8,9. LAB contribute to the conversion of raw materials into the metabolites which confer the taste of fermented foods10,11. The process of kimchi fermentation and the mechanisms of lactic acid bacterial adaptation involved therefore need to be further characterized.

The genus Lactobacillus is the dominant group involved in kimchi fermentation, producing the lactic acid. L. plantarum is beneficial to both food fermentation and human health, and has been designated as a probiotic bacterium by the Korea Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). L. plantarum has been reported to have diverse functionality. Antibacterial activity from L. plantarum was demonstrated to contribute to food preservation and safety12,13,14, and has been found to have probiotic features15,16. Further, L. plantarum prevents intestinal inflammatory disease by controlling cytokine expression17. It has also been isolated from a variety of sources, indicating versatile adaptation in diverse environments18. Bacterial transcriptional analysis provides insight on bacterial gene expression in diverse environmental conditions18,19.

Studies on L. plantarum transcription upon exposure to hydrogen peroxide and p-coumaric acid revealed up- and down-regulation of detoxification function and metabolic functions18,20,21. Gallic acid treatment increased the expression of transport-related genes and was correlated with the proton motive force (PMF) across the membrane22. Transcriptional analysis of L. plantarum adapted at different model such as pineapple and carrot juice, showed that 21–31% of the genes were differently expressed, depending on the plant niche and physiological state of the cell. In both the model systems, L. plantarum showed a large number of up-regulated genes that correspond to carbon and nitrogen metabolism18.

The gene expression of LAB under acidic conditions must therefore be characterized to evaluate bacterial adaptation and subsequent metabolite production. In this study, we analyzed L. plantarum gene expression under acidic conditions to identify and understand the important elements of their adaptation in fermentative environments.

Results

L. plantarum transcriptome analysis

Transcriptome data analysis was performed using FPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million) values of the processed data. The expression value was normalized to a z-score and hierarchial clustering was performed. By means of gene enrichment analysis, we determined several different GO or KEGG terms and metabolic pathways that were enriched with significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes (Enrichment with ENSG option with q < 0.04 with Ben. Ho. FDR). The KEGG categorical enrichment showed an increase of purine and ribosomes, while fatty acid biosynthesis and ABC transport function were down-regulated (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Genes were considered differentially expressed when the pH was 5.0 vs. standard MRS (pH 6.2) and the Log2FC value was > 1 or < − 1. DEG analysis demonstrated that gene expression increased for 25 genes and decreased for 13 genes (Table 1).

Transcriptome data analysis. The bacteria were cultivated for standard MRS (pH 6.2) and acidic MRS adjust pH 5.0 with lactic acid for 3 h, respectively. The heatmap was generated using the z-score value of the transcriptome (a). The categorically annotated Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) data have been presented as a bar graph, and the genes have been represented in the supplementary data. Genes by functional categories that were up-regulated (red) and down-regulated (green) in the acidic conditions (b). The growth of bacteria under acidic conditions was spectrophotometrically monitored at A600 nm (c). The brackets represent p and FDR (q) values and the genes are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

The following genes with amine biosynthetic functions were significantly up-regulated: alanine, aspartate metabolism (pyrAA), and amino acid metabolism-related genes (cblB, cbs, cysE); PTS system genes (pts4ABC); extracellular transglycosylase genes (lp_0302, lp_0304, lp_3014, lp_3050); oligo-peptide ABC transporter genes (lp_0018, lp_0783); nicotinamide nucleotide transporter genes (pnuC1); copper transporting ATPase genes (copA, copB); and carbamoyl phosphatase genes (pyrAB, pyrAA, pyrC). Genes denoting maltose phosphorylase (mapB), manganese transport (mntH3), amino acid transport protein (lp_3278), amine transport, ABC transporter (livA), manganese ABC transporter (mtsC), and glycosylphosphotransferase (cps4E) were significantly down-regulated (Table 1). The results of transcriptome analysis were validated using quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2). The KEGG functional category was annotated into the data and deposited in NCBI (GEO series accession number GSE143834).

Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes under acidic conditions and qRT-PCR quantification. The volcano plot was generated with the difference in gene expression vs. the p-value (a). Gene expression was quantified using real-time RT-PCR. The relative expression was calculated by ΔΔCT method (b). The red and green bars represent the up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively.

Effect of transport inhibitor on bacterial growth in acidic conditions

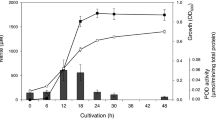

In order to investigate its transport function, L. plantarum growth was monitored and compared between different acidic conditions ranging from pH 6.2 to 5.0. The ABC transport inhibitor valinomycin was added to the culture and bacterial growth was monitored. Valinomycin has been reported to inhibit ABC-type transport in bacteria23. L. plantarum growth was reduced by addition of 5–20 µg/ml of valinomycin and inhibited by 40 µg/ml of valinomycin (Fig. 3a). To evaluate the effect of acidity on bacterial nutrient uptake, the intracellular leucine content was monitored at different pH values in accordance with bacterial growth with 10 µg/ml of valinomycin. Leucine is an auxotrophic amino acid for L. plantarum, and it is known to be transported by ABC-type transport into the intracellular space24,25,26.

Effect of valinomycin on L. plantarum growth and intracellular leucine content under different acidic conditions. The effect of valinomycin on the growth of L. plantarum was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm and visibly monitored (a). L. plantarum was cultivated with 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, or 160 μg/ml valinomycin. The L. plantarum growth and intracellular leucine content was determined at pH 6.2 (b,e), pH 5.5 (c,f), and pH 5.0 (d,g), respectively. The red line and grey bar indicate the presence of 10 µg/ml valinomycin (*p < 0.05).

Lactobacillus plantarum growth was mostly affected by the addition of valinomycin. However, growth was restored at the later growth stage (Fig. 3b–d). The intracellular leucine content was at its maximum at 8 h of culture (189.3 ± 7.5–232.7 ± 11.0 µg/ml), and was found to be 232.7 ± 11.0 µg/ml at pH 5.5. This concentration is 201.0 ± 4.0 µg/ml in MRS or 189.3 ± 7.5 µg/ml at pH 5.0, despite higher growth in MRS than at pH 5.5. The addition of valinomycin significantly decreased the intracellular leucine content at all pH ranges (p < 0.05).

Valinomycin addition decreased the intracellular leucine content by 23–40%. In MRS (pH 6.2), the leucine content was decreased by 23.2% at 6 h and 35.5% at 8 h. Minimum intracellular leucine inhibition was detected in media with pH 5.5, with a 12.3% and 20.5% decrease detected at 2 h and 6 h, respectively (Fig. 3e–g). This inhibition was lower than that in MRS or pH 5.0 media. Next, we compared the growth inhibition between other LAB. Bacterial growth and inhibition upon valinomycin treatment was compared with Lactobacillus brevis, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Leuconostoc lactis, Lactobacillus sakei, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and Weissella confusa and showed the growth reduction at 5–20 µg/ml and the growth inhibition at 40 µg/ml concentration (Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, the LAB showed different degrees of inhibition in the presence of valinomycin. There was no difference in L. brevis and W. confusa growth in the presence of valinomycin. Interestingly, the growth of L. sakei was slightly inhibited by valinomycin at a lower pH (pH 5.5–5.0) (Fig. 4).

Lactic acid bacteria growth under different acidic conditions in the presence of valinomycin. Bacterial was cultivated in MRS media, and the pH was adjusted with lactic acid. Bacterial growth was monitored spectrophotometrically at 600 nm. The red line indicates the addition of valinomycin to the culture (10 µg/ml).

Discussion

Lactobacillus plantarum is a facultative hetero-fermentative gram-positive bacterium. It is an extremely versatile LAB, and has been isolated from the gastrointestinal tract, meat, fish, raw and fermented products27. L. plantarum has one of the largest genomes among LAB, but analysis of its genome sequence has demonstrated that it does not show evolved traits specializing the gene for specific environments28.

An acidic environment is the most common element observed during fermentation. This contributes to inhibition of undesired bacterial growth, which is usually pathogenic and disrupts fermentation. However, acidic conditions also affect the adaptation of LAB. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG modulates its pyruvate metabolism depending on the growth pH, and possesses amino acid transport and adhesion-related genes29.

Previous report showed that the pH changes from pH 6 to pH 4 during the fourth week of fermentation. The pH in the kimchi was dramatically decreased at the first week, as it lowered from pH 6 to pH 5 due to the sharp increase of the LAB5,30. So this periods are important for the bacterial adaption.

In this study, we found that acidic conditions (pH 5) affected the expression of genes located in the functional categories of purine metabolism, ribosomes, fatty acid biosynthesis, and ABC transport (Fig. 1). DEG analysis showed that specific genes were significantly up- (FC > 1) or down-regulated (FC < 1) (Table 1). Several genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, especially transglycosylase genes, were up-regulated. Previous studies have reported that alteration of carbohydrate metabolism under acid stress conditions enables bacteria to better resist acid stress by increasing their energy supply31.

Phosphotransferase system (PTS) genes were observed to be up-regulated under conditions of oxidative stress, such as upon H2O2 or hydroxybenzoic acid exposure20. Interestingly, copper export ATPase gene (copA, copB) expression was increased. Previous research has shown that under oxidative stress, the copper export ATPase (copB) gene of L. plantarum is inactivated. This enhances its sensitivity to the oxidative stress conditions induced by H2O2 and Cu+ or Cu2+ participating in essential redox reactions32.

The expression and transport activity of ABC transporters are tightly regulated to balance the need for essential nutrients. Expression of DalS, the substrate binding protein (SBP) of the d-alanine ABC transporter (STM1633–STM1636) in Salmonella typhimurium, limits exposure to oxidative damage by d-amino acid oxidase in neutrophils33. Increased ABC-type oligopeptide transport proteins (opp) are associated with starvation conditions due to transport changes. Opp function as sensors for environmental change genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and transport, thus counteracting amino acid starvation34. These results show that much of the gene expression observed under acidic conditions is similar to that observed under oxidative stress conditions.

Altogether, bacterial transport was mostly affected by acid stress conditions. Five of the 13 significantly down-regulated genes and 7 of the 25 significantly up-regulated genes possess transport-related functions (Table 1). These results suggest that acidic conditions affect bacterial adaptation, particularly regarding nutrient transport functions.

Figure 3 shows the growth inhibition of valinomycin in culture. Valinomycin effectively inhibited L. plantarum growth even under acidic conditions, indicating that transport functions were active under these conditions.

We previously identified that L. plantarum intracellular leucine and leucine metabolite content was associated with acidity5. The leucine biosynthesis pathways were found to be absent in all L. plantarum strains, as reported in previous studies35, and severe growth inhibition was observed in its absence26. Additionally, it was reported that leucine was transported via the ABC-type transporter36. We therefore quantified the intracellular leucine content of bacteria grown at different pH ranges (Fig. 3).

Although higher bacterial growth was observed in standard MRS (pH 6.2) media, the intracellular leucine content was higher in pH 5.5 culture. This indicates that the optimal bacterial leucine transport could be controlled by acidity during fermentation, and that transport function is most active at approximately pH 5.5. This pH range corresponds to the initial stage of kimchi fermentation (weeks 1–2 of fermentation). Next, we compared the inhibition of the diverse LAB originating from kimchi by valinomycin (Fig. 4).

Lactobacillus plantarum, P. pentosaceus, L. sakei, and L. mesenteroides growth was inhibited by valinomycin, while L. brevis, W. confusa and L. lactis did not demonstrate any difference in growth. The growth of L. sakei was slightly inhibited under acidic conditions of around pH 5.5 and 5.0. These results indicate that the transport function of L. plantarum is active under a wide range of acidic conditions.

Lactic acid easily diffuses into the cytoplasm and dissociates into protons and anions, disrupts the intracellular pH, and impairs normal cellular function31. During fermentation, Lactobacillus transports lactic acid outside the cell as lactate ions via an electrogenic proton-lactate symporter34. In this study, we demonstrated that L. plantarum had a wide range of active transport and acidification functions and modulates leucine uptake. The adaptation of LAB to acidic conditions is a fundamental element of successful fermentation. Interspecies metabolite exchange occurs via nutrient cross feeding. This trophic interaction enables multiple groups of organisms to survive on limited nutrient sources, increasing community density37. The differences in nutrient transport activity among LAB may affect bacterial survival under certain circumstances. Several studies on the stress response of L. plantarum showed higher up- and down-regulation of transport functions in diverse stress conditions induced by resveratrol, hydrogen peroxide, or p-coumaric acid19,20,21. The transport function may, therefore, be a crucial component for adaptation under diverse stress conditions.

These results also suggested that modulating the transport function could be pivotal to controlling fermentation via bacterial growth in the relevant industries.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and culture

A bacterial strain was previously isolated from kimchi and identified previously5,8,38,39. Lactobacillus plantarum wikim18, Leuconostoc lactis WiKim48, Pediococcus pentosaceus WiKim20, Lactobacillus sakei WiKim49, Leuconostoc mesenteroides WiKim19, Weissella confusa WiKim29, and Lactobacillus brevis WiKim47 were used in this experiment.

The bacteria were cultivated at 30 °C for 12 h in De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) media (Miller, Becton Dickinson, and Co., Sparks, MD, USA). The bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 20 min and diluted to into MRS media by absorbance of 0.5 at 600 nm. To monitor the growth effect in the different pH, MRS was prepared with desired pH with addition of lactic acid. The valinomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added into the MRS media at the final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The effect of valinomycin on growth of LAB was measured at 600 nm using microplate reader (Tecan, mannedorf, Zurich, Switzerland).

Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

MIC was measured using twofold serial dilutions methods40. The bacteria was cultivated in MRS media and adjusted to absorbance of 0.01 at 600 nm. The 100 μl of serial diluted valinomycin (from 160 to 5 μg/ml) were added to 100 μl of bacterial suspension in 96 well-plates and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The effect of valinomycin concentration on the bacterial growth was measured at 600 nm using microplate reader (Tecan) and visible growth was monitored after 12 h at 30 °C.

RNA isolation and transcriptome analysis

RNA sequencing was performed at Chunlab (Seoul, Korea). To evaluate the global gene expression of L. plantarum in acidic conditions, the bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 20 min and diluted with acidic MRS adjusted pH with lactic acid (pH 5.0) and standard MRS (pH 6.2) by optical absorbance of 0.5 at 600 nm and further incubated at 30 °C for 3 h. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was stored at − 80 °C until use. The Ribo‐Zero rRNA removal kit (Epicentre, USA) was used for ribosomal RNA depletion according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries for Illumina sequencing were made with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA sample prep kit (Illumina, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform using single‐end 50 bp sequencing. bcl2fastq v1.8.4 software combines per-cycle BCL basecall files generated by Illumina sequencing instruments, translating them into FASTQ files. The raw FASTQ files were split into files containing about 20,000,000 reads and checked for quality using the FASTQC (v0.11.7). The reads were filtered (removing sequences that did not pass Illumina’s quality filter) and trimmed based on the quality results by trimmomatic-0.36. Quality filtered reads were aligned to the reference genome sequence using Bowtie2 (v2.2.3). The sequence data for the reference genome was retrieved from the NCBI database (GCF_000203855.3, L. plantarum WCFS1). Quality filtered reads were aligned to the reference genome sequence using Bowtie2.

Transcriptome data analysis and deposit

The relative transcript-x abundance was measured in fragments in reads per kilobase of exon sequence per million mapped sequence reads (FPKM). The evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (eggNOG) database was used to cluster genes into functionally related groups, and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was used to analyze metabolic pathways. The results of mapping and differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis were visualized using Perseus41,42. Functional annotation was performed using DAVID (DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8)43. DEGs were calculated as log2FC using edgeR in R package44. The RNA-seq data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE143834 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE143834).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was performed to validate the transcriptome analysis data. The gene expression levels were measured using quantitative real-time PCR. The bacteria were cultivated for a further 3 h in MRS media, and pH was adjusted to 5.0 with lactic acid. The bacterial RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 1 µg RNA was reverse transcribed, cDNA was generated, and RT-PCR was performed using SYBR green premix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The relative expression level was calculated and normalized to that of the 16S rRNA gene5. Primers were designed based on nucleotide sequences from L. plantarum of NCBI database (GCF_000203855.3, L. plantarum WCFS1) (Supplementary Table S2).

Quantification of intracellular leucine content

We monitored the effect of pH changes on amino acid transport and the intracellular leucine content using LC–MS/MS technology. A TripleTOF 5600 plus instrument (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) coupled with an Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used to characterize the metabolites and quantify the intracellular and extracellular leucine content of bacteria. Leucine was quantified in negative MRM mode using the following transitions: Leucine, m/z 130 > 130; Salicin, m/z 285 > 123. A reversed-phase column (Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size; Waters) was used to separate the compounds. The mobile phase consisted of distilled water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) containing 10 mM ammonium acetate at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data are presented as means and standard derivations. A two-way analysis of variance test was performed using GraphPad Prism v7 software with the Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

References

Patra, J. K., Das, G., Paramithiotis, S. & Shin, H. S. Kimchi and other widely consumed traditional fermented foods of Korea: A review. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1493. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01493 (2016).

Park, S. & Bae, J. H. Fermented food intake is associated with a reduced likelihood of atopic dermatitis in an adult population (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012–2013). Nutr. Res. 36, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2015.11.011 (2016).

Sharon, G. et al. Specialized metabolites from the microbiome in health and disease. Cell Metab. 20, 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.016 (2014).

Hwang, H. & Lee, J.-H. Chemistry of Korean Foods and Beverages. ACS Symposium Series 3–10 (American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 2019).

Park, B. et al. Identification of 2-hydroxyisocaproic acid production in lactic acid bacteria and evaluation of microbial dynamics during kimchi ripening. Sci. Rep. 7, 10904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10948-0 (2017).

Lee, H.-G., Jeong, S., Park, J. Y. & Yoo, S. Effect of pasteurization on delayed kimchi ripening and regression analysis for shelf life estimation of kimchi. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.915 (2019).

You, S.-Y., Yang, J.-S., Kim, S. H. & Hwang, I. M. Changes in the physicochemical quality characteristics of cabbage kimchi with respect to storage conditions. J. Food Qual. 2017, 9562981. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9562981 (2017).

Hwang, H. & Lee, J. H. Characterization of arginine catabolism by lactic acid bacteria isolated from kimchi. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113049 (2018).

Jung, S., Hwang, H. & Lee, J.-H. Effect of lactic acid bacteria on phenyllactic acid production in kimchi. Food Control 106, 106701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.06.027 (2019).

Hong, S. P., Lee, E. J., Kim, Y. H. & Ahn, D. U. Effect of fermentation temperature on the volatile composition of Kimchi. J. Food Sci. 81, C2623–C2629 (2016).

Lee, S. H., Jung, J. Y. & Jeon, C. O. Source tracking and succession of kimchi lactic acid bacteria during fermentation. J. Food Sci. 80, M1871-1877. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12948 (2015).

Arena, M. P. et al. Use of Lactobacillus plantarum strains as a bio-control strategy against food-borne pathogenic microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 7, 464 (2016).

Sorrentino, E. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum 29 inhibits Penicillium spp. involved in the spoilage of black truffles (Tuber aestivum). J. Food Sci. 78, M1188–M1194 (2013).

Danilova, T. et al. Antimicrobial activity of supernatant of Lactobacillus plantarum against pathogenic microorganisms. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 167, 751–754 (2019).

Liu, Y. W., Liong, M. T. & Tsai, Y. C. New perspectives of Lactobacillus plantarum as a probiotic: The gut-heart-brain axis. J. Microbiol. 56, 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-018-8079-2 (2018).

Al-Tawaha, R. & Meng, C. Potential benefits of Lactobacillus plantarum as probiotic and its advantages in human health and industrial applications: A review. Adv. Environ. Biol. 12, 16–27 (2018).

Le, B. & Yang, S. H. Efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum in prevention of inflammatory bowel disease. Toxicol. Rep. 5, 314–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.02.007 (2018).

Filannino, P. et al. Transcriptional reprogramming and phenotypic switching associated with the adaptation of Lactobacillus plantarum C2 to plant niches. Sci. Rep. 6, 27392. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27392 (2016).

Reverón, I. et al. Transcriptome-based analysis in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 reveals new insights into resveratrol effects at system level. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62, 1700992 (2018).

Zhai, Z. et al. Global transcriptomic analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2 in response to hydrogen peroxide stress. Food Microbiol. 87, 103389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2019.103389 (2020).

Reverón, I., de las Rivas, B., Muñoz, R. & de Felipe, F. L. Genome-wide transcriptomic responses of a human isolate of Lactobacillus plantarum exposed to p-coumaric acid stress. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 56, 1848–1859 (2012).

Reverón, I., de las Rivas, B., Matesanz, R., Muñoz, R. & de Felipe, F. L. Molecular adaptation of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 to gallic acid revealed by genome-scale transcriptomic signature and physiological analysis. Microbial Cell Fact. 14, 1–12 (2015).

Andrade, A. C., Van Nistelrooy, J. G., Peery, R. B., Skatrud, P. L. & De Waard, M. A. The role of ABC transporters from Aspergillus nidulans in protection against cytotoxic agents and in antibiotic production. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263, 966–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00008697 (2000).

Strobel, H. J., Russell, J. B., Driessen, A. & Konings, W. N. Transport of amino acids in Lactobacillus casei by proton-motive-force-dependent and non-proton-motive-force-dependent mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 171, 280–284 (1989).

Poolman, B. Energy transduction in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12, 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-6445(93)90060-M (1993).

Wegkamp, A., Teusink, B., De Vos, W. M. & Smid, E. J. Development of a minimal growth medium for Lactobacillus plantarum. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 50, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02752.x (2010).

Seddik, H. A. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum and its probiotic and food potentialities. Probiotics Antimicrobial Proteins 9, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-017-9264-z (2017).

Martino, M. E. et al. Nomadic lifestyle of Lactobacillus plantarum revealed by comparative genomics of 54 strains isolated from different habitats. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 4974–4989 (2016).

Koponen, J. et al. Effect of acid stress on protein expression and phosphorylation in Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. J. Proteomics 75, 1357–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.009 (2012).

Jeong, S. H., Lee, S. H., Jung, J. Y., Choi, E. J. & Jeon, C. O. Microbial succession and metabolite changes during long-term storage of kimchi. J. Food Sci. 78, M763–M769. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12095 (2013).

Bang, M., Yong, C. C., Ko, H. J., Choi, I. G. & Oh, S. Transcriptional response and enhanced intestinal adhesion ability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG after acid stress. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28, 1604–1613. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1807.07033 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. The copper homeostasis transcription factor CopR is involved in H2O2 stress in Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2015 (2017).

Tanaka, K. J., Song, S., Mason, K. & Pinkett, H. W. Selective substrate uptake: The role of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importers in pathogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 868–877 (2018).

Broadbent, J. R., Larsen, R. L., Deibel, V. & Steele, J. L. Physiological and transcriptional response of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 334 to acid stress. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2445–2458 (2010).

Teusink, B. et al. In silico reconstruction of the metabolic pathways of Lactobacillus plantarum: Comparing predictions of nutrient requirements with those from growth experiments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7253–7262. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.71.11.7253-7262.2005 (2005).

Strobel, H. J., Russell, J. B., Driessen, A. J. & Konings, W. N. Transport of amino acids in Lactobacillus casei by proton-motive-force-dependent and non-proton-motive-force-dependent mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 171, 280–284. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.171.1.280-284.1989 (1989).

Ponomarova, O. et al. Yeast creates a niche for symbiotic lactic acid bacteria through nitrogen overflow. Cell Syst. 5, 345-357.e346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2017.09.002 (2017).

Jang, J. Y. et al. Draft genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum wikim18, isolated from Korean kimchi. Genome Announcements 2, e00467. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.00467-14 (2014).

Park, B. et al. Evaluation of ginsenoside bioconversion of lactic acid bacteria isolated from kimchi. J. Ginseng Res. 41, 524–530 (2017).

Diao, W.-R., Hu, Q.-P., Zhang, H. & Xu, J.-G. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of essential oil from seeds of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Food control 35, 109–116 (2014).

Tyanova, S. & Cox, J. Perseus: A bioinformatics platform for integrative analysis of proteomics data in cancer research. Methods Mol. Biol. 1711, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_7 (2018).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3901 (2016).

Dennis, G. Jr. et al. DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4, P3 (2003).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the World Institute of Kimchi (KE 2002-1), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07043750), Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J. and J.L. designed the study. S.J. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to data interpretation. J.L. supervised the experimental work and data analysis. S.J. and J.L. contributed to manuscript generation. All authors read, reviewed, and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, S., Lee, JH. Characterization of transcriptional response of Lactobacillus plantarum under acidic conditions provides insight into bacterial adaptation in fermentative environments. Sci Rep 10, 19203 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76171-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76171-6

This article is cited by

-

Key Stress Response Mechanisms of Probiotics During Their Journey Through the Digestive System: A Review

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.