Abstract

Biomolecules play key roles in regulating the precipitation of CaCO3 biominerals but their response to ocean acidification is poorly understood. We analysed the skeletal intracrystalline amino acids of massive, tropical Porites spp. corals cultured over different seawater pCO2. We find that concentrations of total amino acids, aspartic acid/asparagine (Asx), glutamic acid/glutamine and alanine are positively correlated with seawater pCO2 and inversely correlated with seawater pH. Almost all variance in calcification rates between corals can be explained by changes in the skeletal total amino acid, Asx, serine and alanine concentrations combined with the calcification media pH (a likely indicator of the dissolved inorganic carbon available to support calcification). We show that aspartic acid inhibits aragonite precipitation from seawater in vitro, at the pH, saturation state and approximate aspartic acid concentrations inferred to occur at the coral calcification site. Reducing seawater saturation state and increasing [aspartic acid], as occurs in some corals at high pCO2, both serve to increase the degree of inhibition, indicating that biomolecules may contribute to reduced coral calcification rates under ocean acidification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical coral skeletons are major components of coral reefs and provide substrates and habitat spaces for fisheries and protection from wave erosion for coastal communities1. Ocean acidification, caused by rising seawater pCO2, typically suppresses the calcification rates of tropical corals and threatens the formation of these structures2. Coral skeletons are formed from semi-isolated extracellular calcification media (ECM) contained between the base of the coral tissues and the underlying skeletons3. Ocean acidification reduces the pH of this ECM (termed pHECM), shifts the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) equilibrium to the detriment of CO32− and likely reduces the ECM saturation state (Ω), a measure of both the [CO32−] and [Ca2+] available for mineral precipitation4. Coral skeletons are composite materials, composed of aragonite (a calcium carbonate polymorph) and organic macromolecules which are disseminated in the mineral phase at the nanoscale5. This intracrystalline skeletal organic matrix (SOM) include proteins, sugars, polysaccharides and lipids and is implicated in the control of mineral precipitation6. For example, primary coral cell cultures produce extracellular organic materials on which aragonite precipitates7 while SOM extracted from tropical, Mediterranean and deep sea coral skeletons affects the precipitation rate, morphology and polymorphism of CaCO3 precipitated in vitro8,9,10. Organic fibrils at the coral calcification site concentrate Ca2+11 and several proteins, lipids and macromolecules resolved from coral SOMs are capable of binding Ca2+12,13. Aspartic acid is typically the most abundant amino acid in the coral SOM12,14 and influences multiple stages of CaCO3 nucleation and precipitation15,16. L-aspartic acid forms complexes with Ca2+, probably via the negatively charged carboxylic acid group (COO−) on the side chain, and this may provide the mechanism to control CaCO3 precipitation and morphology16.

Resolving how the organic component of the skeleton responds to increases in seawater pCO2 is critical to understand the effects of ocean acidification on coral accretion. Increasing seawater pCO2 increases the concentration of skeletal protein observed in coral skeletons17 and is inferred to increase skeletal organic content18. Changes in pHECM in response to increasing seawater pCO2, may alter the net negative charge of biomolecules and thereby influence their control of CaCO3 precipitation19. Here we identify large variations in the amino acid compositions of a suite of massive Porites spp. corals cultured over a range of seawater pCO220,21,22. We find that amino acid concentrations are significantly correlated with coral calcification rates and we explore how aspartic acid, the most prevalent skeletal amino acid, affects skeleton formation by precipitating aragonite in vitro, under fluid conditions analogous to those of the coral calcification site.

Results and discussion

Intracrystalline amino acids and coral calcification

We analysed the intracrystalline amino acids of the skeletons of 3 genotypes of massive Porites spp. corals cultured at 25 °C and at 3 different seawater pCO2 conditions namely 180 µatm, 400 µatm and 750 µatm20,21,22 (Fig. 1, Table S1). Concentrations of total amino acids, aspartic acid/asparagine (termed Asx), glutamic acid/glutamine (termed Glx) and alanine exhibit significant positive correlations with seawater pCO2 and inverse correlations with seawater pH (Table S2). Strongest correlations are observed between these seawater parameters and Asx and are illustrated in Fig. 2a, b. No significant correlations were observed between concentrations of any skeletal amino acids and either pHECM or [H+]ECM.

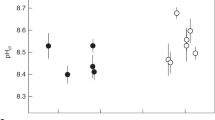

Skeletal amino acid concentrations of each coral genotype (G1, G2 and G3) cultured at 25 °C and over a range of seawater pCO2. Two replicate colonies of G3 were cultured at 400 and 750 µatm. Error bars indicate the mean standard deviation of analyses of duplicate drilled samples. Calcification rates20 (error bar shows typical standard deviation of 3–4 measurements per colony) and calcification site pH21 (adjusted to the pHNBS scale, error bars show 95% confidence limits) are shown for reference. Asx aspartic acid + asparagine, Glx glutamic acid + glutamine.

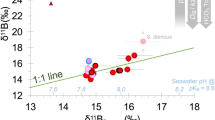

Regressions between skeletal Asx concentration and (a) seawater pCO2, (b) seawater pH and (c) coral calcification rate20.

Significant inverse linear correlations occur between coral calcification rate (reported previously20) and skeletal Asx (Fig. 2c), serine, alanine, Glx and total amino acids (Figure S1, Table S2). Multiple linear regression analysis indicate that a high degree of variance in calcification rate (the dependent variable) is correlated with these amino acid concentrations (the independent variables, p = 0.016, r2 = 0.90, see Table S3 for individual parameters). For comparison r2 = 0.57–0.60 for regressions between coral calcification rate and seawater pCO2 and seawater pH. Precipitation rates of inorganic aragonites are highly dependent on the seawater saturation state, Ω (reflecting the availability of CO32− for incorporation in the CaCO3 precipitate)23. The [CO32] of the calcification fluid is a function of total DIC and pH. Adding the pHECM for these corals (inferred from δ11B analysis of the coral skeletons21) into the regression increases both the significance and coefficient of determination (p = 0.0028, r2 = 0.98, Table S3, Fig. 3). We cultured and analysed two duplicate colonies of the P. murrayensis genotype at 400 and 750 μatm seawater pCO2 and observed large variations in skeletal amino acid concentrations between one pair of duplicates (G3, 750 µatm, Fig. 1). We also observe large variations in pHECM between these corals21 (Fig. 1) but we are able to explain almost all of the variation in coral calcification between them (and the other colonies) on the basis of skeletal amino acids and pHECM in combination.

The concentrations of some amino acids are highly correlated over the dataset e.g. for a linear regression of [Asx] and [Glx] r2 = 0.90. This multicollinearity does not affect the coefficient of determination of the multiple linear regression model (i.e. describing how well the independent variables predict the dependent variable) but does increase the likelihood that we underestimate the significance of one or more amino acids in the regression model and that we misidentify the amino acid which may be responsible for changes in calcification rate.

It is unclear if higher skeletal [amino acid] reflects variations in the coral production of amino acid or enhanced skeletal incorporation of the produced amino acid, but we do not observe consistent relationships between the total skeletal amino acid produced each day (calculated from skeletal concentration and calcification rate20 and seawater pCO2, Figure S2a). We do not observe a significant correlation between the total amount of Asx (or other amino acids) produced each day and coral calcification rate (Figure S2b) to support the interpretation that calcification is limited by an energy budget required to synthesise the skeletal organic matrix21 (assuming that amino acid concentrations are reflective of the total SOM).

Asparagine (and glutamine) undergo deamination during the amino acid extraction process and we cannot separately quantify aspartic acid and asparagine or glutamic acid and glutamine by this method. Proteomic methods, suggest that aspartic acid is a major component of skeletal proteins24 and it is likely that the asparagine contribution to Asx is small. We observe inverse correlations between Asx and both glycine and leucine (Figure S3) which reflect changes in the composition of intracrystalline proteins but the reason for this is unclear.

Interactions of aspartic acid and aragonite precipitation in vitro

The coral skeleton analyses demonstrate that Asx (assumed to be predominantly composed of aspartic acid) is the most prevalent amino acid in the skeletons (Fig. 1) and is the amino acid most strongly correlated with coral calcification rate (Table S2). To explore the potential roles of aspartic acid in coral calcification we precipitated synthetic aragonites from seawater at the approximate pH21 and soluble amino acid concentrations (see “Methods” section) inferred to occur at the coral calcification site. In our initial experiments (at seawater pCO2 = 400 µatm and with pH and omega (Ω) co-varying) aspartic acid inhibited aragonite precipitation and inhibition was more pronounced at higher [aspartic acid] and at lower pH/Ω (Fig. 4). We conducted a second series of experiments, under varying seawater pCO2 with either constant pH (varying Ω) or constant Ω (varying pH) to separate the interactions of pH and Ω with aspartic acid during aragonite precipitation (Fig. 5a, b). A multiple linear regression model of the entire dataset (Table S4) indicates that aragonite precipitation rates are significantly affected by both [aspartic acid] (p = 5.1 × 10–20, Fig. 5c) and Ω (p = 3.2 × 10–58, Fig. 5a) but are independent of pH (p = 0.40, Fig. 5b). As far as we are aware, decoupling the omega and pH, and finding omega to be the principal driver of aspartic acid induced aragonite precipitation inhibition, is a unique observation.

Aragonite precipitation rates from seawater in vitro as a function of [aspartic acid], pH and Ω at seawater pCO2 = 400 µatm. The inset shows the points at pH 8.34 on an expanded axis. Error bars indicate standard deviations of replicate precipitations (n = 2–10) and are usually smaller than the symbols.

The % inhibition of aragonite precipitation (calculated by comparing mean precipitation with aspartic acid with the mean rate observed with no added aspartic acid) as a function of (a) pH at 2 mM aspartic acid and various Ω, (b) Ω at 2 mM aspartic acid and at various pH and (c) [aspartic acid] and Ω. Error bars were calculated by compounding the standard deviations of precipitations with and without aspartic acid.

The interaction of aspartic acid in aragonite precipitation is not fully understood. The precipitation of CaCO3 from a solution can occur via multiple stages, and organic additives have the ability to both promote and inhibit different stages15,16. In brief, homogenous nucleation of CaCO3 occurs in the absence of nucleation sites and likely proceeds via the formation of pre-nucleation clusters of the constituent ions of the solid (or other chemical species) which aggregate and dehydrate to form amorphous solids25. Biomolecules can act as templates for the aggregation of these amorphous nanoparticles which then develop into crystal domains after reaching a critical size26. Heterogeneous nucleation occurs in the presence of existing nucleation surfaces e.g. a mineral seed or an organic material, and requires the formation and subsequent growth of a nucleus on the existing surface. It is not known if ions or clusters of species are involved in these processes25,27. Much of the existing literature on biomolecule interactions during CaCO3 precipitation focuses on calcite and vaterite rather than aragonite and there are contradictory reports of biomolecule effects. Aspartic acid accelerated the nucleation of vaterite in seeded28 and unseeded16 precipitations but stabilised pre-nucleation clusters and delayed CaCO3 nucleation in another report15, consistent with computations indicating that aspartic acid reduces ion dissolution and aggregation in solution29. Interactions of aspartic acid at the solution:solid interface may promote calcite precipitation rate by decreasing the energy barrier to the attachment of solutes19, or may inhibit precipitation by blocking subsequent ion attachment30. Discrepancies between studies may reflect the impact of varying environmental factors, e.g. ionic strength31, pH (affecting molecule charge19), biomolecule concentration19 and the presence of other cations e.g. Mg2+32. Acidic proteins (rich in aspartic acid) can bind to and inhibit extension of specific faces of calcite crystals thereby regulating growth and crystal morphology33 and also bind Ca2+ and catalyse the precipitation of aragonite in vitro34.

In this study, aragonite precipitation from seawater is inhibited by aspartic acid at the concentrations inferred to occur in the coral ECM. Calcite propagation rates were also inhibited at similar [aspartic acid] in lower ionic strength solutions19. Inhibition of precipitation likely reflects aspartic acid adsorption at the crystal:solution interface which impedes the attachment of ions to further CaCO3 growth30. This inhibitory effect is less pronounced at higher Ω (Fig. 5a). Aragonite precipitation rates were constant throughout each precipitation (Figure S4), indicating that the surface area for CaCO3 growth did not change. Variations in precipitation rate between experiments likely reflect crystal growth (rather than pre-nucleation or nucleation events). A potential explanation for our observations is that the ability of aspartic acid to adsorb to aragonite is reduced at high Ω. Increased CaCO3 lattice disorder is inferred in synthetic aragonites precipitated at high seawater Ω in the absence of biomolecules35. This may hamper the ability of aspartic acid to adsorb to the solid:solution interface (and inhibit subsequent precipitation). Alternatively, faster aragonite growth (at high Ω) could itself disadvantage the adsorption of aspartic acid to the growing crystal. It is unlikely that variations in Ω in this study (driven by changes in [CO32−]) significantly affect aspartic acid speciation. Between pH 8 and 9, aspartic acid speciation in seawater is dominated by Mg(asp)H+, Mg(asp)0 and (asp)H- with Ca complexes playing a minor role (< 10% of aspartic acid)36. We observe no significant impact of pH on aragonite precipitation by aspartic acid (Fig. 5b). This likely reflects the large difference between aspartic acid pKa (~ 1.99, 3.90 and 9.90 at 25 °C) and the pH range studied here (pHNBS 8.34–8.69).

We note that the free amino acid used in the precipitations here is not observed in high concentrations in extracts of coral SOM37, where aspartic acid is combined with other amino acids into peptides and proteins. Small aspartic acid-rich peptides inhibit calcite precipitation at lower concentrations than Asp-dipeptides or free aspartic acid19 and adsorbing the amino acid to a template in small pore spaces may influence its effect on CaCO3 precipitation38. However, the interaction of aspartic acid with precipitating CaCO3 is likely due to the acidic carboxylic acid side chain which is present in both the free and protein-bound forms of the amino acid. We interpret our data to indicate an increase in aspartic acid (in whatever form) in the coral ECM under ocean acidification conditions and our in vitro precipitation experiments indicate that an increase in ECM [aspartic acid] could suppress coral calcification at high seawater pCO2.

Implications for coral response to ocean acidification

Our experiments provide insights into the potential role of aspartic acid in coral biomineralisation under ocean acidification scenarios. Corals cultured at 750 µatm pCO2 have higher skeletal [Asx] compared to their genotype analogues cultured at 180 µatm and 400 µatm (by 99% and 61% respectively). ECM Ω in the branching coral Stylophora pistillata cultured at 400 µatm and 25 °C is ~ 1239. At this Ω, raising seawater [aspartic acid] from 0.1 to 0.4 mM (our current best estimate of the ECM concentration in corals cultured at 180 and 750 µatm respectively) increases the biomolecule inhibition of aragonite precipitation from ~ 3 to ~ 11% (Fig. 5c). In reality, the ECM Ω is likely to be reduced at high seawater pCO2, as evidenced by reductions in pHECM4,21 and coral calcification rate2. This Ω decrease will further exacerbate the inhibition of aragonite precipitation by aspartic acid (Fig. 5c). For the colonies analysed here, calcification at 750 µatm is reduced by 49% and 28% compared to the corals cultured at 180 µatm and 400 µatm pCO2 respectively20. We conclude that the inferred change in ECM [aspartic acid] may be responsible for a substantial proportion of this calcification decrease.

Our study demonstrates that coral calcification is affected by both the concentration of organic molecules at the calcification site, and the DIC chemistry in the ECM21. Further research on the response and interactions of ECM organic materials and DIC chemistry to increases in seawater pCO2 and temperature is vital to understanding the response of coral calcification to future climate change.

Methods

Coral culturing experiments

Massive Porites spp. corals were cultured at 25 °C and at 3 different seawater pCO2 conditions (180 µatm, 400 µatm and 750 µatm20,21,22). Heads were imported from Fiji, identified to species level based on corallite morphology and were considered to represent different genotypes when they were collected from spatially separate (non-adjoining) colonies. Heads were sawn into multiple pieces (each ~ 12 cm in diameter) so that at least one piece of each genotype could be cultured in each seawater pCO2 treatment. Corals were maintained at the different pCO2 treatments for 5 months, stained with Alizarin Red S to create a time horizon in the skeletons and then cultured for another 5 weeks before sacrifice. Corals were immersed in 3–4% sodium hypochlorite for 24–48 h with intermittent ultrasonic agitation to remove the tissues, then rinsed in distilled water. A slice was cut through the centre of each coral skeleton, parallel to the maximum growth axis using a water lubricated rock saw, cleaned in an ultrasonic bath and dried. Samples for amino acid analysis were obtained by drilling the skeleton deposited between the skeleton surface and the stain line i.e. representing the final 5 weeks of skeletal growth.

Organic analysis

This method follows the organics analysis in Tomiak et al.40. To isolate the intracrystalline fraction of amino acids < 20 mg of skeletal sample was weighed in to a microcentrifuge tube and bleached using 50 μL 12% NaOCl per mg, the fraction was below 100 μm. The sample was re-agitated over 48 h before the bleach was removed. The remaining sample was rinsed five times by centrifuging with 18.2 MOhm milli-Q 200 μL MeOH was added to the Eppendorf and pipetted off after several minutes. Samples were dried overnight. To hydrolyse samples, < 10 mg was weighed in to a 2 mL sterile vial and 20 μL/mg 7 M HCl was added. Vials were flushed with nitrogen and placed in an oven at 110 °C, vial caps were then retightened to prevent drying. After 24 h, the samples were removed and dried in a centrifugal evaporator. Samples were rehydrated with 10 μL/mg rehydration fluid (0.01 M HCl + 1.5 mM NaN3, spiked with L-homo-arginine). Samples were analysed using reverse-phase HPLC with florescence detection, following the method of Kaufman and Manley41. This enables quantification of L and D isomers of 12 amino acids. Asparagine and glutamine undergo deamination during the preparation process and may therefore contribute to observed concentrations of aspartic acid and glutamic acid. However other methods e.g. proteomics, suggest that skeletal proteins are dominated by aspartic acid24 and we consider the asparagine contribution to be small. Blanks and standards were run throughout; all samples were ran in duplicate.

The precision of amino acid characterisation was estimated by splitting drilled powders before amino acid extraction and by drilling skeletal samples from different sections of the same coral head (Table S1). To estimate the impact of inadvertent inclusion of the Alizarin Red stain in the drilled sample, we compared the amino acid compositions of a sample drilled along the stain line and a powder drilled along a plane parallel to the stain and immediately above it. The amino acid concentrations agree within replicate precision for total, and each of the amino acids with the exceptions of serine and phenylalanine, which both occur in low levels in the skeletons (Table S1). Inclusion of the stain did not affect the mol% of different amino acid groups.

In-vitro aragonite precipitation experiments

Synthetic aragonite was precipitated from seawater using a pH stat titrator (Metrohm Titrando 902) coupled with a gas system designed to produce air with a range of CO2 concentrations20,21,22. We adjusted the pH and [DIC] chemistry of the seawater and added amino acids to explore the impacts of these variables on precipitation. Precipitations were conducted over a pHNBS of 8.34–8.69 (similar to that observed in the coral ECM, Fig. 1) and a [DIC]seawater of 3,000–8,000 µmol kg−1. The coral [DIC]ECM in Stylophora pistillata cultured at 400 µatm and 25 °C is ~ 3,000 µmol kg−139.

Precipitations were conducted in natural seawater (salinity 35) collected from Crail, Fife, filtered (0.45 µm cellulose nitrate filter) and stored in a blacked-out 1000 L high density polyethylene (HDPE) container, under air with a CO2 atmosphere of ~ 400 µatm. For each precipitation, 320 mL seawater was decanted into a HDPE plastic beaker (total volume ~ 360 mL) capped with an ethylene tetrafluoroethylene lid with multiple ports and immersed in a water bath at 25 °C. A high precision combined pH/temperature sensor (Metrohm Aquatrode PT1000), a propeller stirrer, a gas tube and 2 titrant dosing tubes were inserted through the lid and into the headspace (gas tube) or seawater (all others). To avoid invasion or outgassing of CO2, the precipitating solution was maintained under a headspace with an air gas stream with pCO2 set to a value at equilibrium with the solution. Prior to the addition of the seed the gas stream was set to ~ 400 µatm CO2. At the point of seed addition and thereafter the gas stream [CO2] was altered to that in equilibrium with the seawater (calculated using CO2 sys v2.1 from seawater [DIC] and pHNBS using the equilibrium constants for carbonic acid42, for KHSO443 and for [B]44. For each precipitation the amino acid (if used) was added first by suspending the amino acid in 1 mL of seawater and then pipetting this into the reaction vessel. The pH of the seawater was adjusted back to the starting value with the addition of 1.0 M NaOH.[DIC] was increased with the addition of 0.6 M Na2CO3 and the pH adjusted to the required value by addition of 1.0 M HCl or NaOH. Once pH was stable 400 mg of an aragonite seed (from 2 batches of ground coral skeleton with surface areas of 3.45 and 4.41 m2 g−1 as analysed by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller technique)45 was added to the reaction vessel to act as a surface for mineral growth. Precipitation of CaCO3 consumes DIC and Ca2+ and reduces solution pH. The associated pH decrease triggered the titrator to add equal volumes of 0.45 M Na2CO3 and 0.45 M CaCl2. The titration continued until 5 mLs of each titrant had been added resulting in the precipitation of ~ 225 mg of CaCO3. Seawater temperatures within and between precipitations varied by < 0.2 °C. XRD and/or Raman spectroscopy of a least one precipitate produced under each set of conditions confirmed that the original seeds and precipitates were aragonite. Post-precipitation the sensor, beaker and propeller stirrer were submerged in 0.1 M HCl to dissolve any precipitate and then rinsed thoroughly with deionized water.

The pH sensor was calibrated with NIST buffers daily and are reported on the NBS scale. Buffers were replaced each week and the maximum difference observed between old and fresh buffers in a single session was 0.004 pH units. Seawater [DIC] was measured at the start and end of a subset of experiments using an Apollo Sci Tech AS-C3 DIC analyser to ensure that seawater [DIC] was as expected and to monitor for any CO2 invasion or outgas during precipitations. Measured seawater [DIC] agreed with predicted seawater [DIC] within instrumental error46 and [DIC] variations within single precipitations were typically 3% and always < 15%. Seawater [Ca2+] was 10.1 mM as analysed by ICP-OES after 1:50 dilution with 3% HNO3 and spiking with 1 ppm Y as the internal standard. Seawater [Ca2+] was measured using a Ca2+ ion selective electrode (Metrohm) in filtered, acidified (pH 4) samples collected at the start and end of a subset of precipitations. Samples were maintained at constant temperature and measured consecutively to reduce electrode drift. Reproducibility of standards measured before and after samples was ≤ 5% and seawater [Ca2+] at the start and end of the precipitations always agreed within this value.

A sample titration is illustrated in Figure S4 indicating the tight control of pH during precipitation. The aragonite precipitation rate was estimated from the linear fit between time and titrant dosed and was normalized to the surface area of the starting seed. Control experiments, conducted under each set of precipitation conditions but without the addition of seed, demonstrated that no homogenous nucleation occurred in the solutions over the time scale of the precipitation i.e. no dosing of titrants occurred. Each set of precipitation conditions was tested multiple times (n = 2–10) with the exception of the precipitations at Ω = 35.4 which were not replicated. Data for individual precipitations are summarized in the Supplementary information (Table S5).

Identification of amino acid concentrations for precipitation experiments

We precipitated an estimated 225 mg of aragonite from a seawater solution with 2 mM aspartic acid onto 400 mg of inorganic aragonite seed. We estimate that the aragonite precipitated in vitro incorporated [aspartic acid] of 8,554 pmol mg−1 (based on RP-HPLC analysis of the final precipitate and starting seed respectively ([aspartic acid] = 7,700 pmol mg−1 and 17 pmol mg−1 respectively). We estimate an aspartic acidaragonite/aspartic acidseawater partition coefficient of ~ 0.004 (mmol L−1/mmol g−1) indicating that the incorporation of the amino acid in the aragonite has a minimal effect (< 0.5%) on seawater [aspartic acid]. We estimate an [aspartic acid] of the coral calcification media of ~ 0.1–0.4 mM to yield the coral skeletal [aspartic acid] observed in the corals analysed here.

References

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742 (2007).

Erez, J., Reynaud, S., Silverman, J., Schneider, K. & Allemand, D. Coral calcification under ocean acidification and global change. In Coral Reefs: An Ecosystem in Transition (eds Dubinksy, Z. & Stambler, N.) 151–176 (Springer, New York, 2011).

Allemand, D., Tambutte, E., Zoccola, D. & Tambutte, S. Coral calcification, cells to reefs. In Coral Reefs: An Ecosystem in Transition (eds Dubinksy, Z. & Stambler, N.) 119–150 (Springer, New York, 2011).

Venn, A. et al. Impact of seawater acidification on pH at the tissue-skeleton interface and calcification in reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 1634–1639 (2012).

Mass, T., Drake, J. L., Peters, E. C., Jiang, W. & Falkowski, P. G. Immunolocalization of skeletal matrix proteins in tissue and mineral of the coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 12728–12733 (2014).

Falini, G., Fermani, S. & Goffredo, S. Coral biomineralization: a focus on intra-skeletal organic matrix and calcification. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 46, 17–26 (2015).

Helman, Y. et al. Extracellular matrix production and calcium carbonate precipitation by coral cells in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 54–58 (2008).

Falini, G. et al. Control of aragonite deposition in colonial corals by intra-skeletal macromolecules. J. Struct. Biol. 183, 226–238 (2013).

Reggi, M. et al. Biomineralization in mediterranean corals: the role of the intraskeletal organic matrix. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 4310–4320 (2014).

Reggi, M. et al. Influence of intra-skeletal coral lipids on calcium carbonate precipitation. CrystEngComm 18, 8829–8833 (2016).

Clode, P. L. & Marshall, A. T. Calcium associated with a fibrillar organic matrix in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Protoplasma 220, 153–161 (2003).

Puverel, S. et al. Soluble organic matrix of two Scleractinian corals: partial and comparative analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 141, 480–487 (2005).

Isa, Y. & Okazaki, M. Some observations on the Ca2+-binding phospholipid from scleractinian coral skeletons. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 87, 507–512 (1987).

Cuif, J. P., Dauphin, Y., Freiwald, A., Gautret, P. & Zibrowius, H. Biochemical markers of zooxanthellae symbiosis in soluble matrices of skeleton of 24 Scleractinia species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 123, 269–278 (1999).

Picker, A., Kellermeier, M., Seto, J., Gebauer, D. & Cölfen, H. The multiple effects of amino acids on the early stages of calcium carbonate crystallization. Zeitschrift fur Krist. 227, 744–757 (2012).

Tong, H. et al. Control over the crystal phase, shape, size and aggregation of calcium carbonate via a L-aspartic acid inducing process. Biomaterials 25, 3923–3929 (2004).

Tambutté, E. et al. Morphological plasticity of the coral skeleton under CO2-driven seawater acidification. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9 (2015).

Coronado, I., Fine, M., Bosellini, F. R. & Stolarski, J. Impact of ocean acidification on crystallographic vital effect of the coral skeleton. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–9 (2019).

Elhadj, S., De Yoreo, J. J., Hoyer, J. R. & Dove, P. M. Role of molecular charge and hydrophilicity in regulating the kinetics of crystal growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 19237–19242 (2006).

Cole, C., Finch, A. A., Hintz, C., Hintz, K. & Allison, N. Effects of seawater pCO2 and temperature on calcification and productivity in the coral genus Porites spp.: an exploration of potential interaction mechanisms. Coral Reefs 37, 471–481 (2018).

Allison, N. et al. The effect of ocean acidification on tropical coral calcification: insights from calcification fluid DIC chemistry. Chem. Geol. 497, 162–169 (2018).

Cole, C., Finch, A., Hintz, C., Hintz, K. & Allison, N. Understanding cold bias: variable response of skeletal Sr/Ca to seawater pCO2 in acclimated massive Porites corals. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–8 (2016).

Burton, E. A. & Walter, L. M. Relative precipitation rates of aragonite and Mg calcite from seawater: temperature or carbonate ion control. Geology 15, 111–114 (1987).

Ramos-Silva, P. et al. The skeletal proteome of the coral Acropora millepora: the evolution of calcification by co-option and domain shuffling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2099–2112. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst109 (2013).

Gebauer, D., Kellermeier, M., Gale, J. D., Bergström, L. & Cölfen, H. Pre-nucleation clusters as solute precursors in crystallisation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 2348–2371 (2014).

Pouget, E. et al. The initial stages of template-controlled CaCO3 formation revealed by cryo-TEM. Science 323, 1455–1458 (2009).

Demichelis, R. et al. Simulation of crystallization of biominerals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48, 327–352 (2018).

Malkaj, P. & Dalas, E. Calcium carbonate crystallization in the presence of aspartic acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 4, 721–723 (2004).

Finney, A. R. & Rodger, P. M. Probing the structure and stability of calcium carbonate pre-nucleation clusters. Faraday Discuss. 159, 47–60 (2012).

Sikirić, M. D. & Füredi-Milhofer, H. The influence of surface active molecules on the crystallization of biominerals in solution. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 128, 135–158 (2006).

Tai, C. Y. & Chen, F. B. Polymorphism of CaCO3 precipitated in a constant-composition environment. AIChE J. 44, 1790–1798 (1998).

Sand, K. K., Pedersen, C. S., Matthiesen, J., Dobberschütz, S. & Stipp, S. L. S. Controlling biomineralisation with cations. Nanoscale 9, 12925–12933 (2017).

Addadi, L. & Weiner, S. Interactions between acidic proteins and crystals: stereochemical requirements in biomineralization. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. 82, 4110–4114 (1985).

Mass, T. et al. Cloning and characterization of four novel coral acid-rich proteins that precipitate carbonates in vitro. Curr. Biol. 23, 1126–1131 (2013).

DeCarlo, T. M. et al. Coral calcifying fluid aragonite saturation states derived from Raman spectroscopy. Biogeosciences 14, 5253–5269 (2017).

De Stefano, C., Foti, C., Gianguzza, A., Rigano, C. & Sammartano, S. Chemical speciation of amino acids in electrolyte solutions containing major components of natural fluids. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 7, 1–8 (1995).

Puverel, S. et al. Evidence of low molecular weight components in the organic matrix of the reef building coral, Stylophora pistillata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 147, 850–856 (2007).

Cantaert, B., Beniash, E. & Meldrum, F. C. The role of poly(aspartic acid) in the precipitation of calcium phosphate in confinement. J. Mater. Chem. B 1, 6586–6595 (2013).

Sevilgen, D. S. et al. Full in vivo characterization of carbonate chemistry at the site of calcification in corals. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7447 (2019).

Tomiak, P. J. et al. Testing the limitations of artificial protein degradation kinetics using known-age massive Porites coral skeletons. Quat. Geochronol. 16, 87–109 (2013).

Kaufman, D. S. & Manley, W. F. A new procedure for determining DL amino acid ratios in fossils using reverse phase liquid chromatography. Quat. Sci. Rev. 17, 987–1000 (1998).

Lueker, T. J., Dickson, A. G. & Keeling, C. D. Ocean pCO2 calculated from dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity, and equations for K1 and K2: validation based on laboratory measurements of CO2 in gas and seawater at equilibrium. Mar. Chem. 70, 105–119 (2000).

Dickson, A. Standard potential of the reaction: AgCl (s) + 12H2 (g) = Ag (s) + HCl (aq) and the standard acidity constant of the ion HSO4 − in synthetic sea water from 273.15 to 318.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 22, 113–127 (1990).

Uppström, L. The boron/chlorinity ratio of deep-sea water from the Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr. 21, 161–162 (1974).

Brunauer, S., Deming, L. S., Deming, W. E. & Teller, E. On a theory of the van der Waals adsorption of gases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62, 1723–1732 (1940).

Evans, D., Webb, P. B., Penkman, K., Kröger, R. & Allison, N. The characteristics and biological relevance of inorganic amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) precipitated from seawater. Cryst. Growth Des. 19, 4300–4313 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (Research project Grant 2015-268 to NA, RK, and KP) and the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/G015791/1 to NA and AF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A., K.P., R.K. and A.F. designed the study. N.A., A.F., K.H. and C.H. built the culturing system, C.C. and N.A. cultured the corals, C.K. and N.A. conducted the precipitation experiments. D.E., C.K. and K.P. prepared and analysed the samples for amino acid analysis. C.K., N.A. and K.P. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kellock, C., Cole, C., Penkman, K. et al. The role of aspartic acid in reducing coral calcification under ocean acidification conditions. Sci Rep 10, 12797 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69556-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69556-0

This article is cited by

-

The genome of Symbiodiniaceae-associated Stutzerimonas frequens CAM01 reveals a broad spectrum of antibiotic resistance genes indicating anthropogenic drift in the Palk Bay coral reef of south-eastern India

Archives of Microbiology (2023)

-

Effects of seawater pCO2 on the skeletal morphology of massive Porites spp. corals

Marine Biology (2022)

-

Resolving the interactions of ocean acidification and temperature on coral calcification media pH

Coral Reefs (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.