Abstract

Perennially ice-covered lakes that host benthic microbial ecosystems are present in many regions of Antarctica. Lake Untersee is an ultra-oligotrophic lake that is substantially different from any other lakes on the continent as it does not develop a seasonal moat and therefore shares similarities to sub-glacial lakes where they are sealed to the atmosphere. Here, we determine the source of major solutes and carbon to Lake Untersee, evaluate the carbon cycling and assess the metabolic functioning of microbial mats using an isotope geochemistry approach. The findings suggest that the glacial meltwater recharging the closed-basin and well-sealed Lake Untersee largely determines the major solute chemistry of the oxic water column with plagioclase and alumino-silicate weathering contributing < 5% of the Ca2+–Na+ solutes to the lake. The TIC concentration in the lake is very low and is sourced from melting of glacial ice and direct release of occluded CO2 gases into the water column. The comparison of δ13CTIC of the oxic lake waters with the δ13C in the top microbial mat layer show no fractionation due to non-discriminating photosynthetic fixation of HCO3– in the high pH and carbon-starved water. The 14C results indicate that phototrophs are also fixing respired CO2 from heterotrophic metabolism of the underlying microbial mats layers. The findings provide insights into the development of collaboration in carbon partitioning within the microbial mats to support their growth in a carbon-starved ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous perennially ice-covered lakes have been inventoried in Antarctica, including in the McMurdo Dry Valleys (MDV), Bunger Hills, Vestfold Hills, Schirmacher Oasis, and Soya Coast1,2. These lakes have varied chemistries as a result of source water and Holocene history of the lakes, but many are oligotrophic and support benthic cyanobacterial mats and heterotrophic bacterial communities3,4,5. Primary productivity is often limited by light attenuation through the ice-cover and nutrient availability (e.g., C and P), however, summer moating and streams provide seasonal recharge of nutrients to the lakes4,6. Analysis of carbon isotopes (e.g., δ13C, 14C) can provide insights about the source of carbon and transformations of organic matter as photosynthesis and remineralization control the isotopic composition of most organic matter. For example, carbon isotope geochemistry of dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13CDIC) and organic carbon (δ13CDOC) have been used to trace carbon sources and cycling in the MDV lake ecosystem3,7,8,9.

Lake Untersee is a 169-m deep ultra-oligotrophic lake that is substantially different from other lakes in Antarctica10,11. It is recharged by subaqueous melting of glacial ice and subglacial meltwater, and the lake remains ice-covered with no open water along the margin (summer moating) that would provide access to nutrients, CO2 and enhanced sunlight12,13,14. In the absence of large metazoans, photosynthetic microbial mats cover the floor of the lake from just below the ice cover to depths exceeding 130 m, including the formation of small cupsate pinnacles and large conical structures growing in a light and nutrients-starved waters; to date, Untersee is the only freshwater lake hosting the formation of modern large conical stromatolites12,15. Metagenomic sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene showed that the top layer of the microbial mats is composed of a community of carbon-fixing cyanobacteria (Phormidium sp., Leptolyngbya sp., and Pseudanabaena sp) that shifts to a heterotrophic community in the underlying layers (Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes) with amino acid-, carbohydrate-, and arsenic-predicted metabolisms16. The photosynthetic mats are active but with much lower gross photosynthesis and sequestration rates of organic carbon than mats in MDV lakes15.

Previous work at Lake Untersee characterized the geochemistry of the water column10,11,17 and examined the structure of the microbial communities16. However, studies have yet to explore the effect of the absence of summer moating on weathering, the carbon sources and carbon cycling in the lake ecosystem. Here, we assess the source of major solutes and carbon to Lake Untersee, carbon cycling and functioning of the microbial ecosystem using an isotope geochemistry approach. This objective was accomplished by determining the concentration of major ions, δ34SSO4 and Sr-isotopes, total inorganic carbon (TIC), total organic carbon (TOC), δ13C and 14C of the TIC and TOC in the lake water column and the abundance of organic carbon, δ13C, and 14C in the microbial mats. The results are compared to existing biogeochemistry datasets of firn cores from Dronning Maud Land and ice-covered lakes in the McMurdo Dry Valleys that develop summer moats. The findings have relevance to ice-covered lakes on early Mars and ice-covered oceans of icy moons such as Enceladus18.

Study area

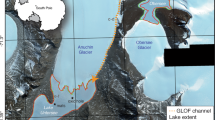

Lake Untersee (71° 20.736′ S; 13° 27.842′ E) is located in the Untersee Oasis in a steep-sided valley in the Gruber Mountains, approximately 90 km southeast of the Schirmacher Oasis and 150 km from the coast19 (Fig. 1). The local geology consists of norite, anorthosite and anorthosite-norite alternation of the Precambrian Eliseev anorthosite complex20. Lake Untersee developed at 12–10 ka BP and measures 2.5 km wide and 6.5 km long, making it the largest freshwater lake in central Dronning Maud Land (DML)10. Untersee Oasis is part of a polar desert regime, the climate subjecting the area to intense ablation limits surface melt features due to cooling associated with latent heat of sublimation (e.g., Refs.13,21, 22).

(A) Location map of Lake Untersee in central Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. (B) Cross-section of bathymetry of Lake Untersee and location of sampling in north and south basins. Background Digital Globe satellite imagery, December 7, 2017; ©2020 Digital Globe NextView License (provided by NGA commercial imagery program). Map generated using ArcGISv10.

Lake Untersee has two sub-basins; the largest, 160 m deep, lies adjacent to the Anuchin Glacier and is separated by a sill at 50 m depth from a smaller, 100 m deep basin to the south. The northern deep basin is well-mixed due to buoyancy-driven convection caused by melting of the ice-wall at the glacier-lake interface11,23; however, the smaller southern basin is chemically stratified below the sill depth (c. 50 m) and its higher density prevents mixing with the overlying oxic water column24,25. Lake Untersee loses c. 1% of its water annually from the sublimation of the 2–4 m thick ice cover. To maintain hydrological balance the lake must be recharged by an equal inflow (i.e., Refs.13,26). The lake is dammed at its northern sector by the Anuchin Glacier and mass balance calculations suggest that subaqueous melting of terminus ice contributes 40–45% of the annual water budget with subglacial meltwater contributing the remainder13. Based on δD-δ18O of the water column, the lake has not developed a moat for at least the past 300–500 years17. The oxic water column has a Na(Ca)–SO4 geochemical facies with uniform temperature (0.5 °C), pH (10.5), dissolved oxygen (c. 150%), specific conductivity (c. 505 µS cm–1) and chlorophyll (0.15 µg L−1)11,12. The nutrients are very low with TIC (0.14 mg C L−1), NO3 (0.2 mg L−1), NO2 (0.11 mg L−1), NH4 (40 µg L−1) and phosphate (< 1 µg L−1)15,27. Approximately 5% of incident irradiance is transmitted through the lake ice, with a vertical extinction coefficient for scalar photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 0.033 m−1, resulting in a 0.1% surface irradiance depth of ~ 135 m12. Lake Untersee supports an exclusively microbial ecosystem along its lake bed with photosynthetic microbial mat communities observed to depths of at least 130 m12,15. The mats are composed of filamentous cyanophytes that form mats, cm-scale cuspate pinnacles, and large conical stromatolites that rise up to 70 cm above the lake floor. The mats are characterized by lamina of organic material and silt- and clay-sized sediments with occasional blocky plagioclase crystals. The fine-grained sediment enters the lake as glacial flour through subglacial melting and deposited on the microbial mats.

Results and discussion

Source of major solutes to Lake Untersee

Lake Untersee has a Na(Ca)–SO4 geochemical facies with [SO42−], [Na+] and [Ca2+] of 166 ± 0.7, 61.8 ± 1.2, 45.7 ± 1.2 mg L−1, respectively (Fig. 2). The δ34SSO4 values range from 7.6 to 8.7‰. The water column is also characterized by Sr+ (18 ± 0.2 µg L−1) with very radiogenic 87Sr/86Sr ratios (0.71804–0.71832; Table 1). To gain insight into the source of solutes to Lake Untersee, the major solutes and their isotopes are first compared to firn cores from the DML region. The nearby Core Epica in western DML is characterized by a similar Na-SO4 facies but with solute concentration 3–4 orders of magnitude lower than in the lake28. The water column in Lake Untersee undergoes cryo-concentration of solutes as water is frozen onto the bottom of the ice cover and the solutes remain mostly in the water column (i.e., Refs.29,30). The effective segregation coefficient (Keff) during freezing varies between solutes as it is dependent on solubility, molecular symmetry and the structure of the crystal lattice29. A recent study of lake ice formation calculated from their freezing experiments that the segregation coefficient is similar for Ca-Na-Cl (Keff: 0.133–0.177), however, it is much higher for SO4 (Keff: 0.299 ± 0.025) indicating that more SO4 is incorporated in the ice30. If we first correct the solute concentration for ionic segregation during freezing using the Keff for respective solutes, the effect of solute enrichment by cryo-concentration can then be removed by normalizing the solutes to Cl−, a conservative tracer.

(A) Geochemical profiles in North and South basins of Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Ionic content, δ34SSO4, δ13CTIC and F14CTIC. (B) Molar ratios (Ca/Cl, Na/Cl, SO4/Cl and DIC/Cl) in Lake Untersee compared to DML Core Epica and weathering of plagioclase minerals. Weathering simulation were performed with PHREEQC hydrogeochemical modeling. See Table 2 for description. Al albite, An anorthite, Ka kaolinite.

Lake Untersee has significantly higher SO4/Cl ratios (1.765 ± 0.002) compared to those in Core Epica (0.89 ± 0.61) (one-way ANOVA, F = 25.88; p < 0.001). The lake also has significantly lower δ34SSO4 (7.6 to 8.7‰) than the δ34Stot values from nearby CV and CM (14.5–15‰; Ref.31). The difference in SO4/Cl ratios and δ34SSO4 indicates the input of SO4 to Lake Untersee is c. 50% higher with a depleted δ34S composition relative to the firn cores from western DML. The western DML cores are situated 400–600 km from the Untersee Oasis and span only the past 50–1,500 years, whereas Lake Untersee has been accumulating solutes since its formation c. 12–10 ka years ago. Despite these spatio-temporal differences in the SO4 data, and in the absence of a deep ice core with SO4 and δ34S measurements from DML, inferences on possible SO4 sources to Lake Untersee can still be made. First, a local source of SO4 can be ruled out since sulfate evaporites are not found in the vicinity of the Untersee Oasis. Secondly, volcanic eruptions are identifiable as distinct SO4 peaks in ice cores and have δ34S values in the 0 to 5‰ range32. Core Epica shows five SO4 volcanic peaks between 1932 and 1991 (representing c. 2% of total SO4 in the core); however, the EDC96 SO4 record shows that volcanic SO4 contributed ~ 6% of the total SO4 during the Holocene33. Finally, the concentration of SO4 and δ34SSO4 from Dome C and Taylor Dome ice cores are 2–3× higher and c. 2‰ lower (9.5–12.6‰), respectively, during the last glacial maximum than during the Holocene as a result of increased meridional transport of marine biogenic SO4 and terrestrial dust34,35,36. Therefore, despite the differences in SO4/Cl and δ34SSO4 between Lake Untersee and the nearby DML firn cores, it appears that SO4 in the lake is sourced from glacial meltwater. Considering that Lake Untersee formed c. 12–10 ka years ago during deglaciation, the initial late Pleistocene glacial meltwater filling the basin would likely have had a higher SO4/Cl with depleted δ34S signature relative to shallow firn cores from western DML. Then, continuous recharge from glacial meltwater during the Holocene with likely higher volcanic SO4 and SO4-bearing terrestrial dust load (both with low δ34S; i.e., Refs.32,37), as evidenced from the EDC96 SO4 record, also contributed to the SO4 in Lake Untersee.

Lake Untersee also has significantly higher Na/Cl and Ca/Cl molar ratios (2.468 ± 0.0483 and 1.048 ± 0.027, respectively) compared to those in Core Epica (0.494 ± 0.213 and 0.0336 ± 0.0365, respectively (one-way ANOVA, Na/Cl: F = 7,013.3, p < 0.001; Ca/Cl: F = 770.2, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The higher ratios can be explained in part to the higher [Na+] and [Ca2+] in glacial ice during last glacial maximum34, however the Na/Cl at Dome C only averages 1.83 ± 1.80 over the past 44 ka34. References10,27 suggested that the enrichment in Na+ and Ca2+ can be attributed to weathering of silicate minerals (i.e., plagioclase: albite, anorthite and kaolinite). X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that the mineralogy of the fine particles in the mats includes anorthite (40–58%) and kaolinite (7–10%), with a few discrete sand layers having higher quart/tremolite. Here, we test the effect of plagioclase weathering in the water column under closed-system condition, which simulates a well-sealed lake with no exchange of gases. Geochemical modeling using PHREEQC hydrogeochemical software38 predicts that closed-system (PCO2 = –10) weathering of plagioclase minerals from glacial meltwater would generate water with a pH of 7.7–11.7 with a range of Na/Cl and Ca/Cl ratios that depend on the mineral assemblage: in all modeled scenarios Ca/Cl ratios (18 to 542) were higher than values in Lake Untersee; however only weathering of the mineral assemblage with albite yielded Na/Cl ratios higher than the lake (Table 2). Therefore, a two-component mixing calculation between the modeled Ca/Cl and Na/Cl ratios and glacial meltwater composition from Core E suggests that weathering of plagioclase contributes a minor portion of the Na+ and Ca2+ load (< 5%) relative to solutes contributed from glacial melt.

Strontium in Lake Untersee is considerably more radiogenic (0.71804–0.71832) than the local anorthosite and norite (0.7079–0.7118), dust in glacial ice (0.708047–0.711254) and modern sea-water (0.70918) (Table 1). Therefore, a more radiogenic source of Sr is needed to explain the Sr isotope ratios in the lake. Refs.39,40 demonstrated the preferential solubilization of 87Sr in the early stages of weathering of glacial deposits due to the rapid weathering of biotite relative to plagioclase. Although the regional basement rocks are dominantly anorthosite, norites and some dykes, the morainic material contains boulders of varied lithology including biotite-bearing gneisses. Thus, weathering products from glacial scouring and/or subglacial weathering of the biotite-bearing gneiss may enrich the 87Sr/86Sr in the lake waters with respect to the signature in the local Eliseev anorthosite complex.

The hydrological conditions of Lake Untersee play a key role on determining the major solute chemistry of the oxic water column. The closed-basin lake loses water only by sublimation of its ice cover and is recharged by subaqueous melting of glacial ice and subglacial meltwater with no summer moating13. The major solutes in Lake Untersee reflect a heritage of 12–10 ka of recharge from glacial meltwater and cryo-concentration of the ionic load in the water column. Early in its existence, the lake would have received a higher ionic concentration from late Pleistocene glacial meltwater that shifted to lower ionic load from glacial meltwater during the Holocene (i.e., Refs.34,35,36). Weathering of local plagioclase contributes a small fraction of ions and Sr isotopes suggest weathering from biotite-bearing gneisses within the drainage basin. However, it is still unclear if weathering occurs primarily while glacial flour is suspended in the lake, within the mats on the lake floor where a higher pCO2 from respiration would enhance weathering, or in the subglacial meltwaters along the basement rocks.

Source, fixation and cycling of carbon in Lake Untersee

The oxic water of Lake Untersee has TIC concentration near detection limit (0.3–0.4 mg C L−1) with δ13CTIC ranging from –6.8 to –9.8‰ (average = –9.1 ± 0.4‰) (Fig. 2). The measured TIC concentration are similar to those measured by Ref.15 (0.14 mg C L−1), but significantly lower than values reported by Ref.25 (DIC: 2–8 mg C L–1; δ13CDIC: 4.3‰). The higher DIC and δ13CDIC measured by Ref.25 is likely due to atmospheric contamination during sampling and filtering of samples in the field. When exposed to air during filtering, the poorly-buffered high pH lake water (pH 10.5) quickly exchanges with atmospheric CO2; PHREEQC modeling calculates DIC of 1.5 mg C L−1 and δ13CDIC 3‰ for lake water equilibrating with atmospheric CO2. The TOC in the oxic water was below the detection limit (< 0.3 mg C L–1) in most samples (one sample at 40 m depth in the south basin yielded DOC of 0.4 mg C L−1 with δ13CDOC of – 27.5‰). However, two composite 1L samples analyzed for 14CTOC yielded 0.27 mg C and 0.22 mg C, suggesting that TOC is c. 0.12 mg C L–1. The TOC is about one order of magnitude lower than in other perennially ice-covered Antarctic surface lakes (c. 2.4 mg C L−1; Ref.41), but is closer to the average compiled for Antarctic glacial ice determined from a range of ice sheet and valley glaciers (0.14 mg C L−1; Ref.42). Tritium (3H) and radio-iodine (129I) measurements were below detection limit in the water column (< 0.8 TU and < 7.5 × 105 atoms L–1, respectively). Radiocarbon analysis of TIC yielded similar F14CTIC (0.414 to 0.436), which is equivalent to apparent ages of 6,666 ± 98 to 7,054 ± 88 years BP (Table 3). For 14CTOC, two pairs of samples were combined to obtain sufficient carbon for analysis (NB-10 and NB-40; NB-60 and NB-120) and yielded F14CTOC of 0.42 ± 0.02 (6,906 ± 610 years BP) and 0.55 ± 0.02 (4,734 ± 606 years BP), respectively (Table 3).

The TIC (0.35 mg C L−1) and δ13CTIC (– 9.1 ± 0.4‰) in Lake Untersee are first compared to six oligotrophic closed-basin lakes in the MDV. The wide range in DIC (2 to 1,000 mg C L−1) and δ13CDIC values (– 5 to 10‰) of the MDV lakes are a product of current and past recharge mechanisms, conditions of the ice cover, and biogeochemical processes occurring in the lakes, including mineralization of organic matter and dissolution of CaCO3. The DIC is brought into the MDV lakes by ephemeral proglacial streams and its concentration is largely influenced by ice cover phenology: DIC is higher in lakes that did not lose their ice cover over the past few millennia and the effect of cryo-concentration (i.e., Bonney, Vanda, Fryxell); DIC is lower in lakes that lost their ice cover due to CO2 degassing and calcite precipitation as the pH decreased (i.e., Hoare, Joyce; Refs.3,8,43). The δ13CDIC of the MDV lakes also shows that DIC is not a limiting factor to primary productivity of photosynthetic mats. When abundant CO2 is available for carbon fixation by the Rubisco enzyme, photosynthetic activity preferentially utilizes 12C, producing microbial mats with depleted δ13C and leaving the residual DIC enriched in 13C7,44,45. The maximum fractionation factor by cyanobacteria ranges from 1.023 to 1.01846,47, which is the difference in δ13CDIC and δ13Cmats in many MDV lakes7,45,48. Conversely, re-mineralization of δ13C depleted organic matter would produce δ13CDIC with similarly low values, as seen near the bottom of Lake Vanda7. Based on the findings of MDV lakes, a low TIC in Lake Untersee is unexpected considering that Untersee has been well-sealed for the past few hundred years17 and likely throughout most of the history of the lake due to the paucity of calcite in the mats12. The mats in Lake Untersee are active, albeit with a lower gross photosynthesis and sequestration rates of organic carbon than mats in MDV lakes15, and as such the δ13CDIC would be expected to be similar to those in the MDV lakes. A significant question then is, why are the TIC and δ13CTIC in Lake Untersee so different from those in the MDV lakes?

The much lower DIC concentration in Lake Untersee can be attributed to the absence of ephemeral surface streams feeding the lake and its rather unique recharge mechanism: glacial meltwater that does not come in direct contact with the atmosphere. The subaqueous melting of the Anuchin Glacier releases occluded air directly into the water column and the occluded atmospheric CO2 gas in the ice then becomes a contributor to the TIC pool. Concentrations of TIC and δ13CTIC in the subaqueous meltwater can be estimated from the occluded gas volume and its age, firn porosity at the depth of closure and CO2 concentration. The Anuchin Glacier at the lake-glacier interface is c. 160 m thick and likely contains occluded gases with an average age of 1,800 years (i.e., based on age-depth relation of occluded gases from nearby EDML ice core;17). Assuming an average gas volume of 0.11 cm3 g–1 in ice49,50 and an average CO2 concentration of 300 ppm for the late Holocene51, a TIC concentration of 0.0165 mg C L–1 is estimated for the contribution of subaqueous meltwater; this value is 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than the [DIC] in streams feeding the MDV lakes43. The direct release of atmospheric CO2 gases into the water column is not a fractionating process, and the δ13CTIC would preserve the δ13C of occluded CO2 gas (δ13CCO2 from Dome C, and Talos Dome range from –7.3 to –6.3‰; Refs.52,53). Lake Untersee is also recharged by subglacial meltwater, and the DIC in this environment can originate from three sources: melting of basal ice, dissolution of carbonates or oxidation of organics in the bedrock; all three sources have δ13C and 14C composition that differ substantially. In the Precambrian anorthosite bedrock, the carbonate and organics would be 14C dead with δ13C values near 0 and c. – 25‰, respectively54. This which would result in much lower the F14CTIC of the water column and vastly different δ13CTIC. Therefore, a major contribution from subglacial carbonate dissolution or oxidation of organic carbon (i.e., Refs. 55,56) can be ruled out, and the DIC in the subglacial meltwater is likely the result of basal melting with a similar TIC and δ13CTIC as the direct melting of the Anuchin Glacier. Dissolution of occluded CO2 undergoes hydrolysis to hydrolytic acid (H2CO3) in the lake, which is then utilized in weathering reactions of plagioclase: the resulting HCO3 and thus DIC would have the same δ13C and 14C composition as the source CO257. The DIC/Cl cannot be used to infer the contribution of other sources of DIC to the lake because DIC/Cl in lake is much lower than potential inputs due to significant sequestering of carbon by the mats. The δ13CTIC (– 9.1 ± 0.4‰) is slightly lower to the δ13C of occluded atmospheric CO2 in Antarctic ice cores (– 7.3 to – 6.3‰; Refs.52,53) and the minor depletion can be attributed to oxidation of the trace amount of DOC with low δ13C in the water column. However, the fact that δ13CTIC is not enriched over δ13CCO2, like most lakes in the MDV, suggest that photosynthesis is not fractionating the DIC reservoir. This can occur in an environment where the phototrophic activity is carbon-starved, and isotope fractionation by cyanobacteria becomes negligible (i.e., Ref.44).

The δ13C and 14C of the microbial mats provide evidence that Lake Untersee is an isotopically indiscriminate carbon-starved ecosystem that utilizes HCO3 and CO2 sources for phototrophic carbon fixation. The organic C abundances and δ13Corg of the microbial mats range from 1.0 to 5.8 wt% and – 6.9 to – 18.1‰, both with a general decrease with depth (Fig. 3). Several mat laminae from the three cores were radiocarbon dated, and the top laminae reported radiocarbon ages of 10,875 ± 37 years BP (Core 1), 10,052 ± 56 years BP (Core 2) and 9,524 ± 48 years BP (Core 3) (Table 4). The bottom mat layers were dated at 16,208 ± 65 years BP (Core 1), 12,031 ± 68 years BP (Core 2) and 13,049 ± 90 years BP (Core 3). Despite some age reversals, a general increase in 14C age is observed with depth, indicating that mats are slowly building biomass at a rate of c. 2.5 mm per 100 years. The δ13CTIC in lake waters (– 9.1 ± 0.4‰) is similar to the δ13C of the top layer of microbial mats (Core 1 = –11.5‰, Core 2 = –9.2‰ and Core 3 = –9.2‰), indicating that little to no 13C fractionation is occurring between the DIC pool and the cyanobacteria during carbon fixation. The pH of Lake Untersee is high (~ 10.5) and the dominant DIC species are HCO3– and CO32–. The cyanobacteria are therefore actively transporting HCO3– into their cells where carbonic anhydrase subsequently catalyzes the production of dissolved CO2 used for carbon fixation (e.g., Refs.44,58). Considering that this process is energetically costly, the cyanobacteria use all of the transferred HCO3- and no 13C fractionation ensues. The 14C results indicate that the cyanobacteria are also fixing respired CO2 from heterotrophic metabolism in the underlying microbial mats layers. The top microbial mat layer (10,875 ± 37 years BP to 9,524 ± 48 years BP) are c. 3,000 years older than the TIC pool in the lake waters (14CTIC = ~ 7,000 years BP). Since the mats are accumulating biomass at a rate of c. 2.5 mm per 100 years, the rate of carbon sequestration is not an explanation to the offset. The 14C difference between the TIC and top mat layer is attributed to the cyanobacteria fixing carbon from two sources: (1) the HCO3– in the water column with δ13CTIC of –9.1 ± 0.4‰ and 14CTIC near 7,000 years BP, and (2) heterotrophically respired CO2 from the decomposition of “older” buried organics with slightly more depleted δ13C. Metagenomic analysis for predictive metabolic functions indicates that the heterotrophic communities are capable of metabolic activities typical of recycling of organic material, such as amino–acid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism16.

(A) Photograph of microbial mats, large conical stromatolites and pinnacles growing in Lake Untersee at 12–13 m depth. Note the clarity of the water column which is a reflection of the nutrient-starved water (e.g., very little DIC or P). (B) Organic carbon content, δ13C and 14C profiles of three microbial mats in Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Cores taken in proximity to photograph shown in A.

Concluding remarks

Stromatolites may be Earth’s oldest macroscopic fossils and provide plausible evidence of a biosphere on Earth 3.45 GYA59,60. Untersee is, at present, the only reported lake hosting the formation of modern, large conical stromatolites morphologically similar to those earliest examples61. The lake and its microbial ecosystem provide a glimpse into early Earth and is regarded as an analogue for Enceladus and potential ice-covered water bodies on early Mars18. Lake Untersee is recharged by subaqueous melting of glacial ice and subglacial meltwater and plagioclase weathering is a minor contributor of Ca2+ and Na+. The lake remains ice-covered with no open water along the margin that would provide access to nutrients, CO2 and enhanced sunlight12,13,14; yet its floor is colonized by active cyanobacteria forming mats, pinnacles and large conical structures growing in a carbon-starved and light-limited waters12. The study highlights the role of carbon cycling within the laminated microbial mats where cyanobacteria utilizes both HCO3 and CO2 for phototrophic carbon fixation. To survive in this carbon-starved system, there is substantial DIC utilization between the cyanobacteria in the top layer of the mats and the underlying heterotrophs.

Methods

Field sampling

Lake water samples were collected at 5–10 m intervals in 2017–2019 using a clean 2.5 L Niskin bottle from holes drilled through the ice cover in the North and South basins. The water samples were immediately transferred into sampling bottles unfiltered due to the sensitivity of the high pH waters to rapid absorption of atmospheric CO2 that would affect pH and DIC. Water samples for major and trace ions, were collected in HDPE bottles; waters for TIC, TOC, δ13CTIC analyses were collected in 40 mL amber glass vials with a butyl septa cap. Radiocarbon samples were collected in pre-baked 1 L amber glass amber bottles.

Benthic microbial mats along the lake bottom were sampled for organic C content, δ13Corg and 14C analyses. Three cores were collected near the eastern edge of the push-moraine at depths of 18.5 m (Core 1), 13 m (Core 2) and 17 m (Core 3) by a scientific diver using SCUBA and pushing a 4 mm diameter polycarbonate tube vertically into the mats. Sodium polyacrylate was added to the waters above the mats in the tube to form a gel seal prior to sealing with a rubber stopper. The gel seal preservation method minimizes disturbances to sediment cores during transport and shows no detectable effects on measurements of organic carbon62.

Lake water analyses

Major ions were measured at the Geochemistry Laboratory at the University of Ottawa. Major cations (Na, Ca, Mg, K, Sr) were acidified upon receipt at the university using 2 µL of trace metal grade 10% nitric acid and measured by an Agilent 4,200 inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer. Major anions (SO4, NO2, NO3, Cl) were measured unacidified using a DIONEX ion-chromatograph. Analytical precision is ± 5% for cations and anions. Charge balance error was < 2.1% when calculated using measured cations-anion and [H+] and [OH–] for an average pH of 10.6.

Barium sulfate (BaSO4) was precipitated from the oxic water samples for stable sulfur isotope (34S/32S) analysis of total and dissolved sulfate to investigate the source of sulfate in the lake waters. The dried and rinsed precipitates were weighed (~ 0.5 mg) into tin capsules with ~ 1 mg of WO3, loaded into the Isotope Cube EA to be flash combusted at 1,800 °C. The released gases were carried by helium through the EA to be cleaned, then separated. The resulting SO2 gas was carried into the Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, Germany) via a conflo IV interface for 34S/32S determination. All δ34S results are reported as permil deviation relative to VCDT and expressed using the delta-notation. The 2σ analytical precision is ± 0.4‰.

Strontium isotope ratios (86Sr/87Sr) were measured in lake waters to investigate potential sources of weathering. The Sr isotope ratios were measured at Queen’s University Facility for Isotope Research (QFIR) using a ThermoFinnigan Neptune MC–ICP–MS with all ratios normalized to 86Sr/88Sr ratio of 0.1194 to account for mass fractionation. Results are reported as the mean of 63 consecutive measurements and corrected to internally normalized NIST standard NBS 987 (87Sr/86Sr = 0.710291). Reported error (2σ) is ± 0.0002 to 0.005. The replicate samples were within the analytical uncertainty.

Tritium (3H) was measured by electrolytic enrichment and liquid scintillation counting. Samples were pretreated prior to enrichment by de-ionizing the waters using an ion-exchange resin and shaken vigorously for 4 h. The deionized waters were mixed with sodium peroxide (Na2O2) and electrolytically enriched in metal cells. Samples were enriched at ~ 5.8 amps for 5 days, reducing the volume from 250 mL to approximately 13 mL. The enriched samples were then decay counted on a low-background Quantilus liquid scintillation counter. Results are reported in tritium units (TU), where1 TU = 0.11919 Bq/L; 2σ analytical precision is 0.8 TU.

Radiodine (129I) was extracted from aqueous samples using a NaI carrier-addition extraction method and precipitated as AgI, using methods described in Marsh (2018). Targets were prepared by mixing 1–2 mg of AgI with high–purity niobium powder, and pneumatically pressed into a stainless–steel cathode for analysis of 129I by AMS (HVE 3MV Tandetron). Measurements were normalized to the ISO–6II reference material by calibration with the NIST 3,230 I and II standards. Results are reported as the measured 129I/127I ratio 10–14 (with carrier), the calculated ratio (without carrier) and the calculated sample 129I concentration (atoms/L). The 129I concentrations without carrier are calculated based on total iodine measured by ICP–MS, amount of I-carrier added, and the AMS measured 129I/127I ratio.

The TIC-TOC concentration and their stable isotope ratios (δ13CTIC, δ13CTOC) in lake waters were measured by a wet TOC analyzer interfaced with a Thermo DeltaPlus XP isotope-ratio mass spectrometer using methods described by Ref.63 at the Ján Veizer Stable Isotope Laboratory, University Ottawa. The isotope ratios are presented as permil deviation relative to VPDB and expressed using the delta-notation. The 2σ analytical precision is ± 0.5 ppm for TOC and TIC concentrations and ± 0.2‰ for δ13CTIC and δ13CTOC. The detection limit of TIC and TOC is < 0.3 ppm.

Radiocarbon analysis of waters was performed at the A.E. Lalonde Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, University of Ottawa. Sample preparation, extraction of inorganic and organic from waters and graphitization is described by Murseli et al.64. Graphitized samples were analyzed on a 3MV tandem mass spectrometer and the 14C/12C ratios are expressed as fraction of Modern Carbon (F14C) and corrected for spectrometer and preparation fractionation using the AMS measured 13C/12C ratio65. Radiocarbon ages are calculated as − 8033ln(F14C) and reported in 14C year BP (BP = AD1950) as described by66. The 2σ errors are reported with the results below and are below 0.013 F14C (or < 190 years).

Microbial mat analyses

The three microbial mat cores were first extruded from the polycarbonate tube onto a clean surface, and each core was divided in half lengthwise using a stainless-steel spatula. The core material consisted of 6–10 cm thick laminated microbial mats that transitioned sharply to sediments. The mat laminae were 0.2–1 mm thick and composed of organic material intermixed with silt and clay-sized particles. In the uppermost section of the cores, the microbial mat laminae were peeled individually, and sampling resolution increased to several laminae (1–10 mm resolution) before the mats transitioned to the underlying sediments which were sampled at 0.5–2 cm resolution. All samples were dried in aluminum trays at 55 °C, weighed, crushed to a powder using a mortar and pestle and acidified with 10% HCl to remove inorganic carbonates.

The mineralogy of sediments in the mats was determined on powdered samples using a Rigaku PXRD using a high intensity 10 mm slit and a scan speed of 0.2° per minute for optimal peak resolution. The resulting intensities were peak matched to mineral phases known to exist in the region and Rietveld Refinement was done to provide relative phase abundances.

Samples were analyzed for organic C content and δ13Corg a by purge and trap chromatography on an elemental analyzer (Vario Isotope Cube, Elementar) coupled via a Conflo III interface to a Thermo DeltaPlus isotope ratio mass spectrometer. All samples were weighed in tin capsules, mixed with tungsten oxide and flash combusted at 1,800 °C with the resulting CO2 gases measured separately by the thermal conductivity detector. The δ13C values are reported against VPDB using internal standards calibrated to international standards. The analytical precision of organic C is ± 0.1% and for δ13C is ± 0.2‰. Results from duplicate samples were within the analytical uncertainty.

Sub-samples of individual laminae of microbial mats in the three cores were submitted to the AMS laboratory for 14C analysis where the samples were pretreated (e.g., freeze-dried, acid-treated to remove inorganic C) according to methods described by Ref.65. For organic C extraction, the pretreated and dried sediments were combusted using a Thermo Flash 1,112 elemental analyzer (EA) in CN mode interfaced with an extraction line to remove non-condensable gases and trap the pure CO2 in a prebaked 6 mm Pyrex breakseal65. The CO2 in the breakseal was graphitized, measured, background corrected and reported using the same methods described for the lake water samples.

Description of ice core datasets

Lake Untersee is recharged by glacial meltwater (subaqueous melting of the Anuchin Glacier and subglacial meltwater), however deep ice core from the Anuchin Glacier and nearby ice field do not exist. To gain insight into solutes content from the glacial meltwater, the chemistry of Lake Untersee is compared to the following ice core datasets.

Western Dronning Maud Land.

CM cores (CM). 360 m a.s.l., 140 km from coast, 30–300 years, δ34Stot. Ref.31.

Core Epica. 700 m a.s.l., 200 km from the coast, 1865–1991. Ionic content. Ref.28.

Core Victoria (CV). 2,400 m a.s.l., 550 km from the coast, 30–1,100 years, δ34Stot. Ref.31.

Dome C. 3,240 m a.s.l., Holocene and late Pleistocene. Ionic content and δ34Stot. Refs.34,34.

Taylor Dome. 2050 m a.s.l. Holocene and late Pleistocene. Ionic content. Ref.35.

Vostok. 3,420 m a.s.l., Holocene and late Pleistocene, δ34Stot. Ref.36.

References

Matsumoto, G. I. et al. Geochemical characteristics of Antarctic lakes and ponds. Proc. NIPR Symp. Polar Biol. 5, 125–145 (1992).

Doran, P. T. et al. Paleolimnology of extreme cold terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. In Long-Term Environmental Change in Arctic and Antarctic Lakes 475–507 (Springer, 2004); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-2126-8_15.

Wharton, R. A., Lyons, W. B. & Des Marais, D. J. Stable isotopic biogeochemistry of carbon and nitrogen in a perennially ice-covered Antarctic lake. Chem. Geol. 107, 159–172 (1993).

Gibson, J. A. E. et al. Biogeographic Trends in Antarctic Lake Communities. In Trends in Antarctic Terrestrial and Limnetic Ecosystems 71–99 (Springer, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5277-4_5.

Hawes, I., Sumner, D. Y., Andersen, D. T. & Mackey, T. J. Legacies of recent environmental change in the benthic communities of Lake Joyce, a perennially ice-covered Antarctic lake. Geobiology 9, 394–410 (2011).

Jungblut, A. D., Lovejoy, C. & Vincent, W. F. Global distribution of cyanobacterial ecotypes in the cold biosphere. ISME J. 4, 191–202 (2010).

Lawson, J., Doran, P. T., Kenig, F., Des Marais, D. J. & Priscu, J. C. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of benthic and pelagic organic matter in lakes of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Aquat. Geochem. 10, 269–301 (2004).

Neumann, K., Lyons, W. B., Priscu, J. C., Desmarais, D. J. & Welch, K. A. The carbon isotopic composition of dissolved inorganic carbon in perennially ice-covered Antarctic lakes: searching for a biogenic signature. Ann. Glaciol. 39, 518–524 (2004).

Hawes, I., Jungblut, A. D., Obryk, M. K. & Doran, P. T. Growth dynamics of a laminated microbial mat in response to variable irradiance in an Antarctic lake. Freshw. Biol. 61, 396–410 (2016).

Hermichen, W.-D., Kowski, P. & Wand, U. Lake Untersee, a first isotope study of the largest freshwater lake in the interior of East Antarctica. Nature 315, 131–133 (1985).

Wand, U., Schwarz, G., Brüggemann, E. & Bräuer, K. Evidence for physical and chemical stratification in Lake Untersee (central Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica). Antarct. Sci. 9, 43–45 (1997).

Andersen, D. T., Sumner, D. Y., Hawes, I., Webster-Brown, J. & McKay, C. P. Discovery of large conical stromatolites in Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Geobiology 9, 280–293 (2011).

Faucher, B., Lacelle, D., Fisher, D. A., Andersen, D. T. & McKay, C. P. Energy and water mass balance of Lake Untersee and its perennial ice cover, East Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 31, 271–285 (2019).

Weisleitner, K., Perras, A., Moissl-Eichinger, C., Andersen, D. T. & Sattler, B. Source environments of the microbiome in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1019 (2019).

Hawes I., Sumner D., & Jungblut A. D. Complex structure but simple function in microbial mats from Antarctic Lakes. In The Structure and Function of Aquatic Microbial Communities. Advances in Environmental Microbiology, Vol. 7 (ed Hurst, C.) (Springer, Cham, 2019) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16775-2_4.

Koo, H. et al. Microbial communities and their predicted metabolic functions in growth laminae of a unique large conical mat from Lake Untersee, East Antarctica. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1347 (2017).

Faucher, B., Lacelle, D., Fisher, D. A., Weisleitner, K. & Andersen, D. T. Modeling δD-δ18O steady-state of well-sealed perennially ice covered-lakes and their recharge source: examples from Lake Untersee and Lake Vostok, Antarctica. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00220 (2020).

McKay, C. P., Andersen, D. & Davila, A. Antarctic environments as models of planetary habitats: University Valley as a model for modern Mars and Lake Untersee as a model for Enceladus and ancient Mars. Polar J. 7, 303–318 (2017).

Bormann, P. The Schirmacher Oasis, Queen Maud Land, East Antarctica and its surroundings. Polarforschung 64, 151–153 (1995).

Paech, H.-J. & Stackebrandt, W. Geology. In The Schirmacher Oasis, Queen Maud Land, East Antarctica and its surroundings (eds Bormann, P., & Fritzsche, D.) 59–159 (Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, 1995).

Andersen, D. T., McKay, C. P. & Lagun, V. Climate conditions at perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee, East Antarctica. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 54, 1393–1412 (2015).

Hoffman, M. J., Fountain, A. G. & Liston, G. E. Surface energy balance and melt thresholds over 11 years at Taylor Glacier, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. 113, F04014 (2008).

Steel, H. C. B., McKay, C. P. & Andersen, D. T. Modeling circulation and seasonal fluctuations in perennially ice-covered and ice-walled Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1139–1155 (2015).

Bevington, J. et al. The thermal structure of the anoxic trough in Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 30, 333–344 (2018).

Wand, U., Samarkin, V. A., Nitzsche, H.-M. & Hubberten, H.-W. Biogeochemistry of methane in the permanently ice-covered Lake Untersee, central Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1180–1194 (2006).

McKay, C. P., Clow, G. D., Wharton, R. A. & Squyres, S. W. Thickness of ice on perennially frozen lakes. Nature 313, 561–562 (1985).

Kaup, E., Loopman, A., Klokov, V., Simonov, I. & Haendel, D. Limnological investigations in the Untersee Oasis. In Limnological Studies in Queen Maud Land (East Antarctica) (ed. Martin, J.) 28–42 (Valgus, Tallinn, 1988).

Isaksson, E. et al. A century of accumulation and temperature changes in Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 101, 7085–7094 (1996).

Killawee, J. A., Fairchild, I. J., Tison, J. L., Janssens, L. & Lorrain, R. Segregation of solutes and gases in experimental freezing of dilute solutions: implications for natural glacial systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 62, 3637–3655 (1998).

Santibáñez, P. A. et al. Differential incorporation of bacteria, organic matter, and inorganic ions into lake ice during ice formation. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 124, 585–600 (2019).

Jonsell, U., Hansson, M. E., Mörth, C. M. & Torssander, P. Sulfur isotopic signals in two shallow ice cores from Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. Tellus Ser. B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 57, 341–350 (2005).

Patris, N., Delmas, R. J. & Jouzel, J. Isotopic signatures of sulfur in shallow Antarctic ice cores. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 7071–7078 (2000).

Castellano, E. et al. Holocene volcanic history as recorded in the sulfate stratigraphy of the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica Dome C (EDC96) ice core. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, D06114. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD005259 (2005).

Wolff, E. W. et al. Southern Ocean sea-ice extent, productivity and iron flux over the past eight glacial cycles. Nature 440, 491–496 (2006).

Mayewski, P. A. et al. Climate change during the last deglaciation in Antarctica. Science 272, 1636–1638 (1996).

Alexander, B. et al. East Antarctic ice core sulfur isotope measurements over a complete glacial–interglacial cycle. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4786 (2003).

Nielsen, H., Pilot, J., Grinenko, L. N., Grinenko, V. A. & Lein, A. Y. Lithospheric sources of sulphur. In Stable Isotopes: Natural and Anthropogenic Sulphur in the Environment (ed. Krouse, H.) 65–132 (Wiley, New York, 1991).

Parkhurst, D. L. & Appelo, C. A. J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3—a computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods, book 6, chapter A43 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-6554(94)90020-5.

Blum, J. D. & Erel, Y. A silicate weathering mechanism linking increases in marine 87Sr/86Sr with global glaciation. Nature 373, 415–418 (1995).

Blum, J. D. & Erel, Y. Rb–Sr isotope systematics of a granitic soil chronosequence: the importance of biotite weathering. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3193–3204 (1997).

Takacs, C. D., Priscu, J. C. & McKnight, D. M. Bacterial dissolved organic carbon demand in McMurdo Dry Valley lakes, Antarctica. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 1189–1194 (2001).

Hood, E., Battin, T. J., Fellman, J., O’Neel, S. & Spencer, R. G. M. Storage and release of organic carbon from glaciers and ice sheets. Nat. Geosci. 8, 91–96 (2015).

Lyons, W. B. et al. The carbon stable isotope biogeochemistry of streams, Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Appl. Geochem. 32, 26–36 (2013).

Hayes, J. M. Factors controlling 13C contents of sedimentary organic compounds: principles and evidence. Mar. Geol. 113, 111–125 (1993).

Hage, M. M., Uhle, M. E. & Macko, S. Biomarker and stable isotope characterization of coastal pond-derived organic matter, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Astrobiology 7, 645–661 (2007).

Calder, J. A. & Parker, P. L. Geochemical implications of induced changes in C13 fractionation by blue-green algae. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 37, 133–140 (1973).

Pardue, J. W., Scalan, R. S., Van Baalen, C. & Parker, P. L. Maximum carbon isotope fractionation in photosynthesis by blue-green algae and a green alga. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 40, 309–312 (1976).

Wada, E. et al. Ecological aspects of carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios of cyanobacteria. Plankt. Benthos Res. 7, 135–145 (2012).

Gow, A. J. & Williamson, T. Gas inclusions in the Antarctic ice sheet and their significance. US Army Corps Eng Cold Reg Res Eng Lab Res Rep (1975).

Samyn, D., Fitzsimons, S. J. & Lorrain, R. D. Strain-induced phase changes within cold basal ice from Taylor Glacier, Antarctica, indicated by textural and gas analyses. J. Glaciol. 51, 611–619 (2005).

Monnin, E. et al. Evidence for substantial accumulation rate variability in Antarctica during the Holocene, through synchronization of CO2 in the Taylor Dome, Dome C and DML ice cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 224, 45–54 (2004).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Eggleston, S., Schmitt, J., Bereiter, B., Schneider, R. & Fischer, H. Evolution of the stable carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO2 over the last glacial cycle. Paleoceanography 31, 434–452 (2016).

Clark, I. Groundwater Geochemistry and Isotopes (CRC Press, Cambridge, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1201/b18347.

Wadham, J. L. et al. Biogeochemical weathering under ice: size matters. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB3025 (2010).

Wynn, P. M., Hodson, A. & Heaton, T. Chemical and isotopic switching within the subglacial environment of a high Arctic Glacier. Biogeochemistry 78, 173–193 (2006).

Graly, J. A., Drever, J. I. & Humphrey, N. F. Calculating the balance between atmospheric CO2 drawdown and organic carbon oxidation in subglacial hydrochemical systems. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 709–727 (2017).

Badger, M. The roles of carbonic anhydrases in photosynthetic CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Photosynth. Res. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025821717773 (2003).

Eigenbrode, J. L. & Freeman, K. H. Late Archean rise of aerobic microbial ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 15759–15764 (2006).

Rasmussen, B., Fletcher, I. R., Brocks, J. J. & Kilburn, M. R. Reassessing the first appearance of eukaryotes and cyanobacteria. Nature 455, 1101 (2008).

Allwood, A. C., Walter, M. R., Kamber, B. S., Marshall, C. P. & Burch, I. W. Stromatolite reef from the early Archaean era of Australia. Nature 441, 714–718 (2006).

Tomkins, J. D., Antoniades, D., Lamoureux, S. F. & Vincent, W. F. A simple and effective method for preserving the sediment–water interface of sediment cores during transport. J. Paleolimnol. 40, 577–582 (2008).

St-Jean, G. Automated quantitative and isotopic (13C) analysis of dissolved inorganic carbon and dissolved organic carbon in continuous-flow using a total organic carbon analyser. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 419–428 (2003).

Murseli, S., et al. The preparation of water (DIC, DOC) and gas (CO2, CH4) samples for radiocarbon analysis at AEL-AMS, Ottawa, Canada. Radiocarbon 61, 1563–1571 https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2019.14 (2019).

Crann, C. A. et al. First status report on radiocarbon sample preparation techniques at the A.E. Lalonde AMS Laboratory (Ottawa, Canada). Radiocarbon 59, 695–704 (2017).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Lyons, W. B., Welch, K. A., Priscu, J. C., Tranter, M. & Royston-Bishop, G. Source of Lake Vostok cations constrained with strontium isotopes. Front. Earth Sci. 4, 78 (2016).

Lyons, W. B. et al. Strontium isotopic signatures of the streams and lakes of Taylor Valley, Southern Victoria Land, Antarctica: chemical weathering in a polar climate. Aquat. Geochem. 8, 75–95 (2002).

Friedman, I., Rafter, A. & Smith, G. I. A thermal, isotopic, and chemical study of Lake Vanda and Don Juan Pond, Antartica. In Contributions to Antarctic Research IV, volume 67 (eds. Elliot, D. H. & Blaisdell, G. L.) 47–74 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118668207.ch5.

Grousset, F. E. et al. Antarctic (Dome C) ice-core dust at 18 k.y. B.P.: isotopic constraints on origins. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 111, 175–182 (1992).

Burton, G., Morgan, V., Boutron, C. & Rosman, K. J. High-sensitivity measurements of strontium isotopes in polar ice. Anal. Chim. Acta 469, 225–233 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the TAWANI Foundation, the Trottier Family Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant, and the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute/Russian Antarctic Expedition. Logistical support was provided by the Antarctic Logistics Centre International, Cape Town, South Africa. We are grateful to Colonel (IL) J. N. Pritzker, IL ARNG (retired), Lorne Trottier, and fellow field team members for their support during the expedition. We thank the two reviewers for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M., D.L., I.D.C., D.T.A. conceived the study and carried out field work; N.M., B.F., S.C., L.J. carried out analyses. N.M., D.L. wrote the main text. All authors discussed the results, edited and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marsh, N.B., Lacelle, D., Faucher, B. et al. Sources of solutes and carbon cycling in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Sci Rep 10, 12290 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69116-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69116-6

This article is cited by

-

Biosignatures of in situ carbon cycling driven by physical isolation and sedimentary methanogenesis within the anoxic basin of perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee, Antarctica

Biogeochemistry (2023)

-

Survival strategies of an anoxic microbial ecosystem in Lake Untersee, a potential analog for Enceladus

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Glacial lake outburst floods enhance benthic microbial productivity in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee (East Antarctica)

Communications Earth & Environment (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.