Abstract

The deep-sea clay that covers wide areas of the pelagic ocean bottom provides key information about open-ocean environments but lacks age-diagnostic calcareous or siliceous microfossils. The marine osmium isotope record has varied in response to environmental changes and can therefore be a useful stratigraphic marker. In this study, we used osmium isotope ratios to determine the depositional ages of pelagic clays extraordinarily rich in fish debris. Much fish debris was deposited in the western North and central South Pacific sites roughly 34.4 million years ago, concurrent with a late Eocene event, a temporal expansion of Antarctic ice preceding the Eocene–Oligocene climate transition. The enhanced northward flow of bottom water formed around Antarctica probably caused upwelling of deep-ocean nutrients at topographic highs and stimulated biological productivity that resulted in the proliferation of fish in pelagic realms. The abundant fish debris is now a highly concentrated source of industrially critical rare-earth elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across the Eocene–Oligocene (E–O) boundary, ca. 33.9 million years ago (Ma), a large-volume ice sheet grew on Antarctica1,2,3. This event and subsequent development of the permanent polar ice sheets during the Cenozoic era occurred after a globally warm period in the early Eocene1,2,3. Several biological proxies extracted from deep-sea sediments have revealed a contemporaneous marine ecosystem shift and biological productivity changes in the Southern Ocean and equatorial Pacific Ocean4,5. However, deep-sea clays in oligotrophic, pelagic realms contain hardly any analogous proxies, such as calcareous or siliceous microfossils.

Microscopic fish skeletal debris are the only fossil remains well preserved in pelagic clay that otherwise lacks fossils. They are predominantly fish teeth and denticles—referred to as ichthyoliths—and bone fragments, all of which are composed of biogenic calcium phosphate6 (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Although they are usually a minor component of the biological proxies in sediments, fish skeletal debris have been effectively used to investigate the response of fish populations to Cenozoic environmental changes in the open ocean7,8. Moreover, the large amounts of fish debris in some pelagic clays from the Pacific9 and Indian10 Ocean have resulted in high bulk contents of rare-earth elements and yttrium (REY)11. Pelagic clay cores collected from the western North Pacific Gyre, for example, include a several-meters-thick layer that contains unusual amounts of fish debris12,13 and has a bulk REY content up to ~8,000 ppm9,12. These previous studies have demonstrated the spatiotemporal variability of fish debris concentrations in pelagic clay. This variability implies that abyssal clay has recorded biotic responses of fish to environmental changes even in the oligotrophic open ocean.

Determination of the depositional age of the pelagic clay containing the anomalous amounts of fish debris allowed us to unravel the causes of the anomalous accumulation of fish debris in the context of contemporaneous environmental changes and biotic responses. Here we determined the depositional ages of pelagic clay layers enriched in fish debris from the western North and central South Pacific Ocean by using a combination of the isotopic ratio of osmium 187Os/188Os in seawater14 and the stratigraphy of ichthyoliths6. The 187Os/188Os ratios in seawater have fluctuated in response to a balance between Os fluxes from continental (riverine), hydrothermal, and extraterrestrial sources15. Fe-oxyhydroxides in deep-sea sediments and ferromanganese (Fe-Mn) crusts record and preserve the 187Os/188Os ratios of seawater at the time of deposition. Therefore, comparison of the measured values of the samples with the marine 187Os/188Os curve14,15 enables determination of the depositional age of each sample16. Ichthyoliths can constrain the depositional ages of pelagic clays based on the stratigraphic ranges of ichthyolith species identified from the morphological features of ichthyoliths6.

Results

Lithologies of the studied sediment cores

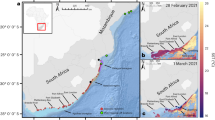

We targeted three pelagic clay core samples collected from the Pacific deep-sea floor for age determination (Fig. 1). Core KR13-02 PC05 was obtained from the deep-sea plain of the northern Pigafetta Basin in the western North Pacific during cruise KR13-02 conducted by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC)12 (Figs. 1 and 2a). Core GH83-3 P406 was obtained from the Penrhyn Basin in the central South Pacific during cruise GH83-3 conducted by the Geological Survey of Japan (GSJ)17 (Figs. 1 and 2b). Core samples from Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Hole 596 were obtained from the Southwest Pacific Basin during DSDP Leg 9118 (Figs. 1 and 2c). Lithologies of these cores12,17,18 are typical pelagic clay composed mainly of clay-sized siliciclastic particles with significant amounts of zeolite (phillipsite) (Fig. 3). The fish debris fraction of core KR13-02 PC05 was less than 5% at depths more than 3.8 meters below the seafloor (mbsf) and peaked at nearly 30% about 3.1 mbsf (Fig. 3, and Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S2). It then decreased to less than 3% above 2.4 mbsf. The fish debris fraction of core GH83-3 P406, which was less than 2% below 5.4 mbsf, peaked at approximately 20% at 5.2 mbsf and then decreased to less than 1% above 3.0 mbsf (Fig. 3, and Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S3). In DSDP Hole 596, the fish debris fraction reached 7–10% at depths below 12.2 mbsf and was less than 3% above 10.7 mbsf18 (Fig. 3). We compared these three cores with two other pelagic clay cores, LL44-GPC3 and DSDP Hole 576 (Figs. 1, and 2d,e), the depositional ages of which had already been constrained by ichthyolith stratigraphy19,20. The calculated fraction of phosphate in core LL44-GPC3, an indicator of fish debris accumulation21, was 7–10% at depths below 15 mbsf and less than 5% above 15 mbsf21 (Fig. 3). In DSDP Hole 576, the fraction of fish debris was only 1% from 26.8 to 28.5 mbsf22 (Fig. 3).

Locations of cores KR13-02 PC05, GH83-3 P406, DSDP Holes 596 and 576, and LL44-GPC3 with the bathymetry of the Pacific Ocean. Sampling sites of Fe-Mn crusts phosphatized during the interval 33–35 Ma38 and those whose phosphatization ages were not constrained67 are also shown. Bathymetric data are from ETOPO168 (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center: 10.7289/V5C8276M; https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/global.html). This map was created by using Generic Mapping Tools software, Version 4.5.1869 (https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/gmt/).

Detailed seafloor topographies around the study sites. (a) KR13-02 PC05, (b) GH83-3 P406, (c) DSDP Hole 596, (d) LL44-GPC3, and (e) DSDP Hole 576. Bathymetric data are from ETOPO168 (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center: 10.7289/V5C8276M; https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/global.html). This map was created with Generic Mapping Tools software, Version 4.5.1869 (https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/gmt/).

Downhole variations of fractions of sediment constituents, ichthyolith ages, and 187Os/188Os ratios in the cores used in this study. Fractions of sediment constituents of cores DSDP Hole 59618 and DSDP Hole 57622 and ichthyolith ages of cores GH83-3 P40617, DSDP Hole 59642, LL44-GPC319, and DSDP Hole 57620 have been previously reported. The rest of the sediments consisted of clay-sized particles. The calculated phosphate content of core LL44-GPC3, an indicator of the amount of fish debris21, was used in this study instead of the reported low-resolution smear slide data70. The 187Os/188Os ratios of LL44-GPC3 has previously been reported23. The following abbreviations of epochs indicate ages based on ichthyolith stratigraphy: M = Miocene, O = Oligocene, E = Eocene, and P = Palaeocene. Abbreviations of epoch adjectives are as follows: e = early, m = middle, and l = late. Question mark means not constrained.

Marine 187Os/188Os records in the study cores

The 187Os/188Os records in cores KR13-02 PC05, GH83-3 P406, and DSDP Hole 596 showed common features (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S2). The 187Os/188Os ratios of the cores showed radiogenic minima of <0.3 at 3.2 mbsf in core KR13-02 PC05, at 5.0 mbsf in core GH83-3 P406, and at 11.0 mbsf in core DSDP Hole 596. Above the horizons associated with these radiogenic minima, the ratios gradually increased with decreasing depth. Near the top of the cores, the ratios increased to radiogenic values of 0.7–1.0. The depth profiles and the ranges of our new 187Os/188Os data were consistent with those of the marine 187Os/188Os curve14,15 in the time interval from the late Eocene to the present (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S4). The previously reported Os isotope compositional data of LL44-GPC323 above 14.0 mbsf showed a trend similar to that of the three cores described above (Fig. 3). The 187Os/188Os ratio showed a radiogenic minimum at 12.2 mbsf and then increased with decreasing depth.

Age assignments and calculated fish debris accumulation rates

The remarkably low 187Os/188Os minima in the cores were all attributable to the 187Os/188Os excursion across the E–O boundary (Fig. 4a,b, and Supplementary Fig. S5). Our age determination procedure based on the combination of Os isotope ratios and ichthyolith stratigraphy is fully described in Methods. The fact that the combined stratigraphy successfully determined the depositional ages of all the sampling points allowed us to reconstruct records of accumulation rates of fish debris (including teeth, denticles, and bone fragments) at each site. These records demonstrated significant changes in the fish debris accumulation rates (FAR) around the E–O boundary at the study sites (Fig. 4a,b). From 34.7 to 34.4 Ma, the FAR at the site of core KR13-02 PC05 increased abruptly to about six times the FAR before 34.7 Ma and peaked between 34.4 and 34.3 Ma. The FAR then decreased abruptly to a value lower than before 34.7 Ma. The FAR record of core GH83-3 P406 showed a similar pattern to that of core KR13-02 PC05. From 34.8 to 34.6 Ma, the FAR increased abruptly to about 12 times the value before 34.8 Ma and peaked between 34.3 and 34.2 Ma. The FAR subsequently decreased abruptly at 34.2 Ma, and after 33.8 Ma it decreased to a value similar to that before 34.8 Ma. In contrast, at 34.9 Ma the FAR was higher at the site of DSDP Hole 596 than at the other study sites but did not show any prominent increase until 34.3 Ma. In our record, the FAR abruptly decreased at 34.2 Ma to a rate much lower than the FARs of the other study cores. This abrupt decrease probably corresponded to the hiatus at 11.7 mbsf that was suggested from the bulk chemical composition24 (Supplementary Fig. S5c,f). The record at the site of DSDP Hole 596 indicated that the FAR suddenly dropped at 34.2 Ma, and that there was no increase before that drop. A previously reported record of the accumulation rate of fish teeth and denticles at the site of DSDP Hole 5968 and our FAR record at the same site agreed with each other in that the rates were nearly constant and without any prominent increases in the time period from the late Eocene to the early Oligocene. This comparison indicates that our FAR record is consistent with the long-term trend of fish debris accumulation, although the previous study counted only teeth and denticles8, whereas our FAR included all phosphatic fish debris (denticles, teeth, and bones). Although the age models at the site of LL44-GPC3 were based on ichthyolith stratigraphy and a constant cobalt flux model that differed from our age model, the mass accumulation rate of phosphate showed no obvious increase around the E–O boundary. In core DSDP Hole 576, a detectable amount (>1%) of fish debris was not observed in the Eocene to Oligocene sequence, based on a smear slide analysis22 (Fig. 3). In summary, prominent and transient increases of fish debris accumulation occurred at the sites of KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406 around 34.5 Ma in the very late Eocene but did not occur at the sites of DSDP Hole 596, LL44-GPC3, and DSDP Hole 576.

The age-assigned 187Os/188Os records in the study cores with fish debris accumulation rates (FARs), age distributions of phosphatized Fe-Mn crusts, and δ18Obf records. (a) 187Os/188Os records in cores KR13-02 PC05, GH83-3 P406, and DSDP Hole 596, with the FARs of these cores and the calculated phosphate accumulation rate of LL44-GPC321, from 40 Ma to the present. The ages of the samples were assigned based on our age determination procedure. (b) Enlarged view of (a) from 36 to 32 Ma. The green shaded lines in (a,b) indicate the EOT and the late Eocene events. Error bars on 187Os/188Os data points indicate 2 S.D. plus the differences between measured values and 187Re decay–corrected initial values (see Methods). Note that error bars of almost all samples are smaller than symbols. (c) δ18Obf obtained from DSDP Sites 52271 and 68972, and ODP Site 12185. Ages of these cores were calibrated by adjusting biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic age benchmarks based on the chronology of the Geologic Time Scale 201262. (d) Histogram of the ages of phosphatized Fe-Mn crust samples from the Pacific Ocean38.

Discussion

From the middle to late Eocene, the opening of the Southern Ocean Gateways—the Drake Passage and Tasman Rise—led to the development of a current around Antarctica shallower than the present Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), the so-called proto-ACC2,25. The possibility that a deep water mass began to form around Antarctica in the late Eocene (ca. 36.5 Ma) and subsequently spread into the North Pacific is supported by the gradual increase of the oxygen isotope ratios of benthic foraminifera (δ18Obf) over a period of about 2.5 million years25.

Subsequently, a critical environmental change occurred around 34 Ma. That change is given special recognition as the E–O climate transition (EOT) and is marked by the onset of a permanent ice sheet on Antarctica, changes of ocean circulation, and a climatic regime shift1,2. These changes have been attributed to a decrease of atmospheric CO2 concentrations26,27, as well as to the opening of the Southern Ocean gateways, which led to thermal isolation of Antarctica2,28. In contrast to the secular changes of ocean circulation due to the opening of the gateway25, the ice-sheet growth is recognized to have occurred in several steps that involved short-term increases of the ice volume on Antarctica5,29,30. The Pacific and Atlantic δ18Obf records have revealed two minor positive shifts called EOT-1 and EOT-25,29 (Fig. 4c). These shifts were followed by a major positive shift referred to as Oi-1 that corresponds to the onset of the permanent Antarctic ice-sheet1,2,5,29,30 (Fig. 4c). About 1 million years before Oi-1, some δ18Obf records display a transient increase by ~0.5‰, which is called the late Eocene event5,29 (Fig. 4c). During that time, ice-volume, seawater temperature, and sea-level changes, based on δ18Obf, the Mg/Ca ratios of foraminiferal shells, and geological records, respectively, collectively indicate expansion of the Antarctic ice volume without changes of tropical sea surface temperature29. Previously reported records of biogenic silica and carbonate accumulation rates in the Southern Ocean have suggested that productivity increased in response to the Oi-1 glaciation4. In the eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean, the record of the benthic foraminifera accumulation rate, a proxy for palaeoproductivity, shows a transient increase at the time of the Oi-1 glaciation5. These simultaneous increases of productivity have been attributed to intensification of oceanic and atmospheric circulation that drove divergence and upwelling of nutrient-rich thermocline waters in these regions4,5.

Because fish are consumers or predators in an ecosystem, the fish population likely reflects surface ocean productivity31. Therefore, the significant increase of FAR at the sites of KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406 may have resulted from greater biological productivity and a larger population of fish at these sites associated with ocean circulation changes toward the end of the Eocene. However, the significantly shorter duration of the FAR increases compared to the time required for reorganization of ocean circulation in response to the gateway opening indicates that the FAR increases were instead related to a short-term event. In addition, the peak of productivity at these sites preceded the major glaciation event of Oi-1 by about 1 Myr (Fig. 4b,c). Moreover, there were no significant increases of productivity at the contemporary sites of DSDP Hole 596, LL44-GPC3, and DSDP Hole 576, although they, as well as the sites of KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406, are located in pelagic areas. It is probable that the higher FAR at 34.9 Ma at the site of DSDP Hole 596 in the South Pacific versus the other sites (Fig. 4b) is a reflection of high biological productivity in the South Pacific during the late Eocene32,33. The differences in the patterns between our records and those from the Southern Ocean4 and eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean5—that is, the timing and spatial pattern of the productivity changes—suggest a fundamental difference in the mechanisms that caused the productivity increases. The productivity increases at the sites of KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406 coincided with the late Eocene event at ~34.4 Ma (Fig. 4b,c), and their durations were more likely equivalent to the time associated with the δ18Obf increase of the late Eocene event than to the duration of the secular δ18Obf change caused by the gateway opening25. The implication is that there was a close relationship between the productivity increases at the two sites and the late Eocene event.

A coupled ocean-atmosphere model that tested the role of the Antarctic ice sheet on changes of ocean circulation during the EOT has demonstrated that growth of the Antarctic ice sheet could have invigorated Antarctic bottom water formation as a result of the high southern latitude cooling34. Therefore, the expansion of the ice sheet during the late Eocene event, although smaller than the expansion at the Oi-1, would have stimulated northward flow of bottom water by cooling Antarctica. Because the circulation of the Eocene ocean was relatively sluggish prior to the initial formation of the Antarctic ice sheet at the late Eocene event, nutrients could have accumulated in the deep ocean35. The intensified northward flow would have resulted in the first stirring of nutrient-rich deep ocean water. This stirring would have led to an upwelling of nutrients to the surface ocean in regions with topographic barriers that were steep and large enough to allow upwelling35 (Supplementary Fig. S6). In the modern ocean, enhanced primary productivity around seamounts is recognized to be a result of upwelling generated by seamount–current interactions31,36. Though seamount–current interactions are complicated oceanographic processes, these currently observed increases of productivity support the hypothesized nutrient upwelling during the late Eocene event. The seamount chains in the present western North Pacific Ocean around KR13-02 PC05 and the Manihiki Plateau near site GH83-3 P406 can likewise enhance upwelling of bottom water (Fig. 2a,b). This supply of nutrients for the first time in oligotrophic pelagic realms may have been sufficient to allow pelagic organisms to flourish. The osmium isotope records (Fig. 4b) suggest that this enhancement of production continued for about a hundred thousand years, at the end of which time the nutrients stored in the deep water of these regions had been consumed and dispersed, and the enhancement of production ceased. This mechanism can explain the differences between the records of palaeoproductivity at the other sites. Because the sites of DSDP Hole 596, LL44-GPC3, and DSDP Hole 576 are located on a vast deep-sea plain without any topographic rises near the sites (Figs. 1 and 2c–e), there would have been no upwelling of nutrient-rich, northward-flowing water.

Other geological observations support this postulated mechanism of enhanced production. The bimodal grain size distribution of the fish debris-rich layer in core KR13-02 PC05, with peaks at ~4 µm and 60–80 µm, indicates a winnowing of the fine silt-sized fraction13,37 (Supplementary Fig. S7). In addition, the grain sizes of fish debris and phillipsite (volcanic in origin) were coarser in the layer rich in fish debris than in the other parts of the sediment column13 (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). The similar grain size patterns of the fish debris and phillipsite, which have different sources (Supplementary Fig. S1), suggests hydraulic fractionation caused by enhanced flow of bottom water13,37. Moreover, active upwelling of phosphate-rich bottom water over the seamount could have promoted phosphatization of Fe-Mn crusts on the central Pacific seamounts from the very late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene (Figs. 1 and 4d). The result would have been a drastic redistribution of phosphorus in the ocean35,38. The geochemical and geological lines of evidence suggest that significant amounts of fish debris could have been deposited on the deep seafloor in the pelagic realm where there were steep and large topographic rises in the late Eocene and where there was an enhanced northward flow of bottom water formed as a result of the ephemeral expansion of the Antarctic ice sheet superimposed on a secular reorganization of ocean circulation.

The synchronous proliferation of fish during the late Eocene event in the western North and central South Pacific sites provides new insights into the distributions of rare-earth elements in the Pacific Ocean sediments. Fossilization of fish debris in pelagic clay led to highly concentrated REY—up to ~20,000 ppm of total REY9. Pelagic clay rich in fish debris can therefore be a promising new source of REY for industry. The distribution of such REY-rich mud9 is very heterogeneous, even in a relatively small area. Bulk chemical composition analyses of the sediment cores in an area of 2,500 km2 in the southern plain at the foot of the Takuyo Daigo Seamount9,12,39 (Supplementary Fig. S8), including core KR13-02 PC05, have indicated that the REY content is very inhomogeneous. A lithological study of the sediment cores (including core P406) collected by the GH83-3 cruise in an area of roughly 100 km × 100 km has also revealed a large variation in their lithologies17. Although these heterogeneities make it difficult to precisely estimate the amount of the REY-rich mud resource, a previous study has shown that REY-rich mud containing large amounts of fish debris to a depth of 10 mbsf in an area of 2,500 km2 around the site of KR13-02 PC05 (Supplementary Fig. S8) can provide as much REY as several hundred years of consumption in the modern world9.

Pelagic clays rich in fish debris have been found in only two areas in this study, KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406 area, but the mechanism of blooming that we proposed in this study allows us to constrain potential areas where similar clays may be found in the Pacific Ocean. On the assumption that such clays could form at the foot of steep topographic rises from ocean basins at depths greater than ~5,000 m (i.e., well below the carbonate compensation depth) and had a relative elevation of several thousands of meters (i.e., sufficiently high to induce an upwelling of bottom water to the surface ocean), the potential area could cover a wide region through the Pigafetta Basin in the western North Pacific, Mid Pacific Mountains, and Penrhyn Basin in the central South Pacific (Supplementary Fig. S6). The actual targets are expected to be relatively small areas located at the foot of steep slopes in the potential area. If this assessment is correct, the clay might be a huge storehouse of elements associated with fish debris such as REY and phosphorous.

We conclude that marine organisms in the pelagic realm of the Pacific Ocean had flourished in response to the fluctuation of oceanic circulation caused by Antarctic cooling during the late Eocene event that preceded the EOT. The intensified northward flow of bottom water formed around Antarctica resulted in the first stirring of nutrient-rich deep ocean water, which led to an upwelling of nutrients to the surface ocean in regions with topographic highs. The global change of the Cenozoic climate also facilitated the incorporation of phosphorus-favoured elements such as REY into pelagic clay.

Methods

Smear slide analysis

The fractions of sediment constituents in some horizons of cores KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406 were determined by smear slide analyses following the protocols of the Ocean Drilling Project (ODP)40 (Supplementary Table S1). We identified clay-sized particles, quartz, feldspar, phillipsite, fish debris, red-brown to yellow-brown semi-opaque oxides (RSOs)41, micro-manganese oxides (Mn-oxides), coloured minerals, and volcanic ash. Microphotographs of the representative horizons are shown in Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3.

Ichthyolith stratigraphy

The ages of cores GH83-3P406 and DSDP Hole 596 had been previously constrained by ichthyolith stratigraphy17,42. For core KR13-02 PC05, approximately 3 g of wet sediment sample was sieved through 62-µm–opening mesh with Milli-Q water. The obtained coarse portions were dried at 40 °C. The amount of the coarse portion of KR13-02 PC05, section 4, 72–74 cm, was reduced by random sampling. All teeth-like fragments contained in each coarse portion were handpicked and enclosed on glass slides using ultraviolet curing resin. Ichthyoliths were identified under a polarizing microscope based on previously published databases of systematic ichthyolith taxonomy20,43,44,45,46. The ichthyolith ages were determined as ranges of ages within which the taxa identified in each sample occurred together. The ichthyolith taxa that occurred in core KR13-02 PC05 are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Microphotographs of representative specimens of ichthyolith species identified in core KR13-02 PC05 are shown in Supplementary Fig. S9.

Os and Re isotope analyses

Our analytical procedures for Os and Re isotopes have been fully described elsewhere47,48. All data obtained from the analyses are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Approximately 1 g of each dried and powdered bulk sediment sample was weighed and spiked with 185Re and 190Os. The samples were then digested in 4 mL of inverse aqua regia in sealed Carius tubes at 220 °C for 24 h to extract the seawater-derived Os from the pelagic sediment49,50,51. Solutions were separated from residues and diluted with Milli-Q water. The Os isotope ratios were measured with a Thermo Scientific Neptune multiple collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at the Department of Solid Earth Geochemistry, JAMSTEC, combined with sparging sample introduction. Measurements of samples were performed by multiple Faraday collectors (FC), and those for procedural blank samples were performed with multiple-ion counters. Os concentrations were determined by isotope dilution and corrected for Os in the blank samples, the average of which was 0.36 ± 0.35 pg with a 187Os/188Os ratio of 0.140 ± 0.051 (n = 5; average ± 1 S.D.).

After the Os measurements, the solutions were heated to remove remaining Os. Re in the sample solutions was purified by two consecutive anion exchange chromatography steps. Measurements of Re for samples and blank samples were performed with an Agilent 7500ce ICP quadrupole mass spectrometer at the Super-cutting-edge Grand and Advanced Research (SUGAR) Program, Institute for Extra-cutting-edge Science and Technology Avant-garde Resarch (X-star), JAMSTEC. Concentrations of Re were determined by isotope dilution and corrected for Re in the blank samples, the average of which was 4.28 ± 1.93 pg (n = 5; average ± 1 S.D.). Concentrations of Re were used to correct measured 187Os/188Os data and to calculate initial 187Os/188Os values, as described below.

In addition to the samples from the study cores, we measured several uppermost sediment samples (0.00–0.02 mbsf) collected near core KR13-02 PC05 on cruises KR13-02 and MR14-E02 (Supplementary Table S2) to confirm that our Os isotopic data represented marine 187Os/188Os values. The 187Os/188Os ratios of these samples ranged from 0.954 ± 0.011 to 0.997 ± 0.012 (Supplementary Table S2). These values are generally consistent with the modern seawater value in the central Pacific (1.044 ± 0.0364052). This result confirmed that the 187Os/188Os data obtained with our analytical procedures reflected seawater values. The 187Os/188Os ratio of the sample near the top of core KR13-02 PC05 (section 1, 2–4 cm) showed a very atypical radiogenic value (0.465) and much lower Os concentration (63.49 pg/g) than the corresponding values in the uppermost sediment samples (0.954–0.997 and 109.13–132.21 pg/g, respectively). We examined a smear slide of this sample under a polarizing microscope and confirmed that this sample contained larger amounts (up to ~50%) of volcanic components such as ash and coloured minerals compared to the other samples. This result indicated that the 187Os/188Os ratio in this sample was probably disturbed by non-radiogenic Os in the volcanic components. Thus, this sample was excluded from the age-assignment procedure described below.

Marine 187Os/188Os curve since 40 Ma

To determine the age of our samples, we compiled a marine 187Os/188Os curve from 40 Ma to the present (Supplementary Fig. S4) based on several published 187Os/188Os data obtained from deep-sea sediment cores53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61. The ages of the cores used in these previous studies were tightly constrained by biostratigraphy and magnetostratigraphy. In addition, we calibrated their ages by adjusting the biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic age benchmarks based on the chronology of the Geologic Time Scale 201262. Thus, this marine 187Os/188Os curve represented the most precise age–187Os/188Os relationship in the ocean. Most previous studies have reported high-resolution marine 187Os/188Os data from ~37 to ~32 Ma and from ~15 Ma to the present, but the temporal resolution of the data in other periods has been relatively low. To complement the reference curve, we employed a long-term record of marine 187Os/188Os ratios obtained from a Fe-Mn crust in the Pacific63 refined by the thallium isotope record in the crust16 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Although there are slight discrepancies in the details of these records, they show generally consistent trends throughout the time interval from 40 Ma to the present.

Procedure of age assignment based on the marine 187Os/188Os record

In previous studies that determined ages using an approach similar to this study16,64, several age benchmarks (e.g., 0 Ma for the present marine 187Os/188Os ratio and a prominent negative excursion around the E–O boundary) were identified, and constant growth rates were assumed between these benchmarks. However, pelagic clays are known to often include sedimentation hiatuses or periods of extremely slow sedimentation65. Thus, the above approach may have resulted in incorrect age assignments for pelagic clays. To avoid this problem, we identified the age of an individual sample by comparing its 187Os/188Os ratio with the age–187Os/188Os relationship of the marine 187Os/188Os curve. The final age assignments were obtained when the best fits were achieved after slight adjustments of fitting not to exceed typical sedimentation rates of pelagic clay (<5 m/Myr)66. Here, we describe how we determined the ages of our samples. To simplify the description, we assigned a sample number (s.n.) to each sample used for the age determination (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. S5).

In core KR13-02 PC05 (Supplementary Fig. S5a,d), s.n. 1 (187Os/188Os = 0.801) corresponded to 11 Ma on the marine 187Os/188Os curve. Then, s.n. 2 (187Os/188Os = 0.801), for which the ichthyolith age represented late Oligocene to early Miocene, should correspond to 20 Ma in the Fe-Mn crust record. The rest of the samples (s.n. 3 to 18; 187Os/188Os = ~0.2–0.6) were characterized by a negative shift of the 187Os/188Os and thus could be fitted to two prominent negative excursions at 35.8 Ma and across the E–O boundary. Use of a typical sedimentation rate of pelagic clay (<5 m/Myr)66 gave a reasonable fit of the series of 187Os/188Os values to the broader negative excursion across the E–O boundary. For the best fit, s.n. 3 to 5 were assigned to between 32.3 and 33.7 Ma, and s.n. 6 to 18 were assigned to between 33.8 and 34.9 Ma. These age assignments for core KR13-02 PC05 are consistent with the age constraints based on ichthyolith stratigraphy (Supplementary Table S3).

For core GH83-3 P406 (Supplementary Fig. S5b,e), s.n. 1 to 4 (187Os/188Os = ~0.7–0.8) could be assigned to between 12 and 16 Ma, where the Fe-Mn crust record shows a small fluctuation. The precise age of s.n. 5 (187Os/188Os = 0.740) could not be specified because it corresponded to a long-term plateau in the marine 187Os/188Os curve. The age of this sample was therefore tentatively assigned by assuming a constant sedimentation rate between s.n. 4 and 6. The rest of the samples (s.n. 6 to 13; 187Os/188Os = ~0.6–0.2), which were characterized by a negative shift of 187Os/188Os ratios, could be assigned to the relatively broad negative excursion across the E–O boundary for the same reason as in core KR13-02 PC05. For the best fit, s.n. 6 and 7 were assigned to 32.0 and 32.8 Ma, and s.n. 8 to 13 were assigned to 34.2 and 34.9 Ma, respectively. These age assignments for core GH83-3 P406 are consistent with the age constraints based on ichthyolith stratigraphy17, with the exception of s.n. 8 and 9, where the ichthyolith age represented the Oligocene to early Miocene. Considering that the resolution of the ichthyolith age was approximately epoch level6, the age assignments of these samples were very close to the E–O boundary and not necessarily inconsistent with the ichthyolith age.

For core DSDP Hole 596 (Supplementary Fig. S5c,f), s.n. 1 to 4 (187Os/188Os = ~0.9) were assigned to ages between 1 to 7 Ma. The s.n. 5 (187Os/188Os = 0.808), where the ichthyolith age represented early Miocene42, could correspond to ~19–21 Ma of the Fe-Mn crust record. The s.n. 6 (187Os/188Os = 0.524), where the ichthyolith age represented early Miocene42, could be assigned to ~23 Ma, where the Fe-Mn crust record showed a transient decrease. The rest of the samples (s.n. 7 to 14; 187Os/188Os = ~0.3–0.4) were associated with a negative shift of 187Os/188Os ratio and could be assigned to the broader negative excursions across the E–O boundary for the same reason as in cores KR13-02 PC05 and GH83-3 P406. For the best fit, s.n. 7 was assigned to 33.8 Ma, and s.n. 8 to 14 were assigned to between 34.2 and 34.9 Ma. These age assignments for core DSDP Hole 596 were consistent with the age constraints based on ichthyolith stratigraphy42. After the age assignments, we checked differences between measured 187Os/188Os values used in the age assignment procedures and the initial 187Os/188Os values calculated by subtracting the radiogenic 187Os generated from internal 187Re decay after deposition (Supplementary Table S2). The fact that the differences between the corrected initial 187Os/188Os values and uncorrected measured values (0.02–1.62%) were less than or almost equivalent to the analytical errors (0.30–3.61%; 2 S.D.) indicates that 187Re decay was negligible for the age assignment procedure.

Dry bulk density, sedimentation rate, and mass accumulation rate

The dry bulk density (DBD) of core KR13-02 PC05 was measured at several depths. The DBD of core DSDP Hole 596 had previously been reported18. The DBD of core GH83-3 P406 has not yet been reported and was assumed to be constant and equal to 0.40 g/cm3, which is comparable to the average DBD of core DSDP Hole 596. We calculated the DBDs of cores KR13-02 PC05 and DSDP Hole 596 by linear interpolation of the measured DBDs; the Os isotope ratios of the same cores were measured (Supplementary Table S2). After determining the ages of cores KR13-02 PC05, GH83-3 P406, and DSDP Hole 596, we calculated the sedimentation rate (SR) in meters per million years (m/Myr) between sample i and i + 1 (SRi,i+1) and the FAR in g/cm2/Myr between sample i and i + 1 (FARi,i+1) with the following equations:

where di is the depth of sample i from the seafloor in meters, ti is the age in millions of years of sample i determined in this study, DBDi,i+1 is the average DBD between sample i and i+1, and fFi,i+1 is the average fraction of fish debris between sample i and i+1.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Change history

31 July 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Zachos, J. C., Pagani, M., Sloan, L., Thomas, E. & Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693 (2001).

Cramer, B. S., Toggweiler, J. R., Wright, J. D., Katz, M. E. & Miller, K. G. Ocean overturning since the Late Cretaceous: Inferences from a new benthic foraminiferal isotope compilation. Paleoceanography 24, PA4216, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001683 (2009).

Cramwinckel, M. J. et al. Synchronous tropical and polar temperature evolution in the Eocene. Nature 559, 382–386 (2018).

Salamy, K. A. & Zachos, J. C. Latest Eocene–Early Oligocene climate change and Southern Ocean fertility: inferences from sediment accumulation and stable isotope data. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 145, 61–77 (1999).

Coxall, H. K. & Wilson, P. A. Early Oligocene glaciation and productivity in the eastern equatorial Pacific: Insights into global carbon cycling. Paleoceanography 26, PA2221, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010PA002021 (2011).

Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Cenozoic and Late Cretaceous ichthyoliths in Plankton Stratigraphy (eds. Bolli, H. M., Saunders, J. B. & Perch-Nielsen, K.) 965–995 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1985).

Sibert, E. C., Hull, P. M. & Norris, R. D. Resilience of Pacific pelagic fish across the Cretaceous/Palaeogene mass extinction. Nat. Geosci. 7, 667–670 (2014).

Sibert, E., Norris, R., Cuevas, J. & Graves, L. Eighty-five million years of Pacific Ocean gyre ecosystem structure: long-term stability marked by punctuated change. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160189, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0189 (2016).

Takaya, Y. et al. The tremendous potential of deep-sea mud as a source of rare-earth elements. Sci. Rep. 8, 5763, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23948-5 (2018).

Yasukawa, K. et al. Geochemistry and mineralogy of REY-rich mud in the eastern Indian Ocean. J. Asian Earth Sci. 93, 25–36 (2014).

Kato, Y. et al. Deep-sea mud in the Pacific Ocean as a potential resource for rare-earth elements. Nat. Geosci. 4, 535–539 (2011).

Iijima, K. et al. Discovery of extremely REY-rich mud in the western North Pacific Ocean. Geochem. J. 50, 557–573 (2016).

Ohta, J. et al. Geochemical factors responsible for REY-rich mud in the western North Pacific Ocean: Implications from mineralogy and grain size distributions. Geochem. J. 50, 591–603 (2016).

Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. & Ravizza, G. Osmium isotope stratigraphy in The Geologic Time Scale 2012 (eds. Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. D. & Ogg, G. M.) 145–166 (Elsevier, 2012).

Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. & Ravizza, G. The marine osmium isotope record. Terra Nova 12, 205–219 (2000).

Nielsen, S. G. et al. Thallium isotope evidence for a permanent increase in marine organic carbon export in the early Eocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 297–307 (2009).

Nishimura, A. & Saito, Y. Deep-sea sediments in the Penrhyn Basin, South Pacific (GH83-3 area) in Geological Survey of Japan Cruise Report Vol. 23 (ed. Usui, A.) 41–60 (Geological Survey of Japan, 1994).

Menard, H. W. et al. Site 596: Hydraulic piston coring in an area of low surface productivity in the Southwest Pacific. Init. Repts. DSDP 91, 245–267 (1986).

Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Cretaceous to Neogene ichthyoliths in a giant piston core from the central North Pacific. Micropaleontology 25, 337–364 (1979).

Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Ichthyolith biostratigraphy of western North Pacific pelagic clays, Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 86. Init. Repts. DSDP 86, 349–366 (1985).

Kyte, F. T., Leinen, M., Heath, G. R. & Zhou, L. Cenozoic sedimentation history of the central North Pacific: Inferences from the elemental geochemistry of core LL44-GPC3. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 1719–1740 (1993).

Heath, G. R. et al. Site 576. Init. Repts. DSDP 86, 51–90 (1985).

Pegram, W. J. & Turekian, K. K. The osmium isotopic composition change of Cenozoic sea water as inferred from a deep-sea core corrected for meteoritic contributions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 4053–4058 (1999).

Zhou, L. & Kyte, F. T. Sedimentation history of the South Pacific pelagic clay province over the last 85 million years inferred from the geochemistry of Deep Sea Drilling Project Hole 596. Paleoceanography 7, 441–465 (1992).

Borrelli, C. & Katz, M. E. Dynamic deep-water circulation in the northwestern Pacific during the Eocene: Evidence from Ocean Drilling Program Site 884 benthic foraminiferal stable isotopes (δ 18O and δ 13C). Geosphere 11, 1204–1225 (2015).

DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Rapid Cenozoic glaciation of Antarctica induced by declining atmospheric CO2. Nature 421, 245–249 (2003).

Pagani, M. et al. The role of carbon dioxide during the onset of Antarctic glaciation. Science 334, 1261–1264 (2011).

Katz, M. E. et al. Impact of Antarctic Circumpolar Current development on late Paleogene ocean structure. Science 332, 1076–1079 (2011).

Katz, M. E. et al. Stepwise transition from the Eocene greenhouse to the Oligocene icehouse. Nat. Geosci. 1, 329–334 (2008).

Cramer, B. S., Miller, K. G., Barrett, P. J. & Wright, J. D. Late Cretaceous–Neogene trends in deep ocean temperature and continental ice volume: Reconciling records of benthic foraminiferal geochemistry (δ 18O and Mg/Ca) with sea level history. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C12023, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007255 (2011).

Rogers, A. D. The biology of seamounts. Adv. Mar. Biol. 30, 305–350 (1994).

Moore, T. C. et al. Paleogene tropical Pacific: Clues to circulation, productivity, and plate motion. Paleoceanogaphy 19, PA3013, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003PA000998 (2004).

Lyle, M. et al. Pacific Ocean and Cenozoic evolution of climate. Rev. Geophys. 46, RG2002, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005RG000190 (2008).

Goldner, A., Herold, N. & Huber, M. Antarctic glaciation caused ocean circulation changes at the Eocene–Oligocene transition. Nature 511, 574–577 (2014).

Hein, J. R. et al. Two major Cenozoic episodes of phosphogenesis recorded in equatorial Pacific seamount deposits. Paleoceanography 8, 293–311 (1993).

Rogers, A. D. The biology of seamounts: 25 Years on. Adv. Mar. Biol 79, 137–224 (2018).

McCave, I. N., Manighetti, B. & Robinson, S. G. Sortable silt and fine sediment size/composition slicing: Parameters for palaeocurrent speed and palaeoceanography. Paleoceanography 10, 593–610 (1995).

Hyeong, K., Kim, J., Yoo, C. M., Moon, J.-W. & Seo, I. Cenozoic history of phosphogenesis recorded in the ferromanganese crusts of central and western Pacific seamounts: Implications for deepwater circulation and phosphorus budgets. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol 392, 293–301 (2013).

Fujinaga, K. et al. Geochemistry of REY-rich mud in the Japanese Exclusive Economic Zone around Minamitorishima Island. Geochem. J. 50, 575–590 (2016).

Mazzullo, J. & Graham, A. G. Handbook for shipboard Sedimentologists. Ocean Drilling Program Technical Note 8, 1–67 (1988).

Yeats, R. S. et al. Site 319. Init. Repts. DSDP 34, 19–80 (1976).

Winfrey, E. C., Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Preliminary ichthyolith stratigraphy, Southwest Pacific, Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 91. Init. Repts. DSDP 91, 447–468 (1987).

Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Ichthyoliths: present status of taxonomy and stratigraphy of microscopic fish skeletal debris. Scripps Institution of Oceanography Reference Series, 79–16 (1979).

Kozarek, R. J. & Orr, W. N. Ichthyoliths, Deep Sea Drilling Project Legs 51 through 53. Init. Repts. DSDP 51, 857–895 (1979). 52, 53.

Gottfried, M. D., Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Advances in ichthyolith stratigraphy of the Pacific Neogene and Oligocene. Micropaleontology 30, 71–85 (1984).

Tway, L. E., Doyle, P. S. & Riedel, W. R. Correlation of dated and undated Pacific samples based on ichthyoliths and clustering techniques. Micropaleontology 31, 295–319 (1985).

Nozaki, T., Suzuki, K., Ravizza, G., Kimura, J.-I. & Chang, Q. A method for rapid determination of Re and Os isotope compositions using ID-MC-ICP-MS combined with the sparging method. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 36, 131–148 (2012).

Kimura, J.-I., Nozaki, T., Senda, R. & Suzuki, K. Precise determination of Os isotope ratios in the 15–4000 pg range using a sparging method using enhanced-sensitivity multiple Faraday collector-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 29, 1483–1490 (2014).

Dalai, T., Suzuki, K., Minagawa, M. & Nozaki, Y. Variations in seawater osmium isotope composition since the last glacial maximum: A case study from the Japan Sea. Chem. Geol. 220, 303–314 (2005).

Kuroda, J., Hori, R. S., Suzuki, K., Gröcke, D. R. & Ohkouchi, N. Marine osmium isotope record across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary from a Pacific pelagic site. Geology 38, 1095–1098 (2010).

Sato, H., Onoue, T., Nozaki, T. & Suzuki, K. Osmium isotope evidence for a large Late Triassic impact event. Nature Commun 4, 2455 (2013).

Sharma, M., Papanastassiou, D. A. & Wasserburg, G. J. The concentration and isotopic composition of osmium in the oceans. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3287–3299 (1997).

Oxburgh, R. Variations in the osmium isotope composition of sea water over the past 200,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 159, 183–191 (1998).

Ravizza, G. Variations of the 187Os/186Os ratio of seawater over the past 28 million years as inferred from metalliferous carbonates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 118, 335–348 (1993).

Reusch, D. N., Ravizza, G., Maasch, K. A. & Wright, J. D. Miocene seawater 187Os/188Os ratios inferred from metalliferous carbonates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 163–178 (1998).

Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B., Ravizza, G. & Hofmann, A. W. The marine 187Os/186Os record of the past 80 million years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 130, 155–167 (1995).

Ravizza, G. & Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. The marine 187Os/188Os record of the Eocene–Oligocene transition: the interplay of weathering and glaciation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 210, 151–165 (2003).

Dalai, T. K., Ravizza, G. E. & Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. The Late Eocene 187Os/188Os excursion: Chemostratigraphy, cosmic dust flux and the Early Oligocene glaciation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 241, 477–492 (2006).

Paquay, F. S., Ravizza, G. & Coccioni, R. The influence of extraterrestrial material on the late Eocene marine Os isotope record. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 144, 238–257 (2014).

Paquay, F. S., Ravizza, G. E. & Dalai, T. K. Determining chondritic impactor size from the marine osmium isotope record. Science 320, 214–218 (2008).

Van der Ploeg, R. et al. Middle Eocene greenhouse warming facilitated by diminished weathering feedback. Nature Commun 9, 2877, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05104-9 (2018).

Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. D. & Ogg, G. M. The Geologic Time Scale 2012 (Elsevier, 2012).

Burton, K. W. Global weathering variations inferred from marine radiogenic isotope records. J. Geochem. Exp 88, 262–265 (2006).

Klemm, V., Levasseur, S., Frank, M., Hein, J. R. & Halliday, A. N. Osmium isotope stratigraphy of a marine ferromanganese curst. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 238, 42–48 (2005).

Hussong, D. M. et al. Site 452: Mesozoic Pacific Ocean Basin. Init. Repts. DSDP 60, 77–93 (1982).

Hesse, R. & Schacht, U. Early diagenesis of deep-sea sediments in Deep-Sea Sediments (eds. Huneke, H. & Mulder, T.) 557–713 (Elsevier, 2011).

Koschinsky, A., Stascheit, A., Bau, M. & Halbach, P. Effects of phosphatization on the geochemical and mineralogical composition of marine ferromanganese crusts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 4079–4094 (1997).

Amante, C. & Eakins, B. W. ETOPO1 1 arc-minute global relief model: Procedures, data sources and analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24, National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, https://doi.org/10.7289/V5C8276M, (accessed: 23rd May 2019) (2009).

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. New, improved version of Generic Mapping Tools released. EOS Trans. Amer. Geophys. U 79, 579 (1998).

Corliss, B. H. & Hollister, C. D. Cenozoic sedimentation in the central North Pacific. Nature 282, 707–709 (1979).

Zachos, J. C., Quinn, T. M. & Salamy, K. A. High-resolution (104 years) deep-sea foraminiferal stable isotope records of the Eocene-Oligocene climate transition. Paleoceanography 11, 251–266 (1996).

Diester-Haass, L. & Zahn, R. Eocene-Oligocene transition in the Southern Ocean: History of water mass circulation and biological productivity. Geology 24, 163–166 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This study used samples provided by JAMSTEC from core KR13-02 PC05, by the International Ocean Discovery Program from core DSDP Hole 596, and by the GSJ through T. Yamazaki from core GH83-3 P406. We thank Y. Otsuki and H. Yamamoto for supporting the Os and Re isotope analyses. We also thank Y. Itabashi for assistance with the ICP-QMS analyses. We are grateful for helpful discussions with H. Iwamori. This study was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through Grants-in-Aid Nos. JP15H05771 to Y.K., JP17H01361 to K.N., JP16K13895 to T.N., JP14J10351 and JP16J07136 to J.O., and JP15H02148, JP16H01123, and JP18H04372 to J.-I.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K. designed this study. J.O. carried out the ichthyolith stratigraphy and smear slide analysis. J.O., K.Y., K.F., K.N., and K.M. conducted the sampling work. J.O., T.N., Y.T., J.-I.K., and Q.C. performed Os and Re isotope analyses. Y.U. measured the dry bulk density. J.O., K.Y., K.F., K.N. and Y.K. primarily wrote the manuscript with inputs from all other co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohta, J., Yasukawa, K., Nozaki, T. et al. Fish proliferation and rare-earth deposition by topographically induced upwelling at the late Eocene cooling event. Sci Rep 10, 9896 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66835-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66835-8

This article is cited by

-

K-feldspar enrichment in the Pacific pelagic sediments before Miocene

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2023)

-

Magnetostratigraphic evidence for post-depositional distortion of osmium isotopic records in pelagic clay and its implications for mineral flux estimates

Earth, Planets and Space (2021)

-

Unmixing biogenic and terrigenous magnetic mineral components in red clay of the Pacific Ocean using principal component analyses of first-order reversal curve diagrams and paleoenvironmental implications

Earth, Planets and Space (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.