Abstract

Wild potatoes, as dynamic resource adapted to various environmental conditions, represent a powerful and informative reservoir of genes useful for breeding efforts. WRKY transcription factors (TFs) are encoded by one of the largest families in plants and are involved in several biological processes such as growth and development, signal transduction, and plant defence against stress. In this study, 79 and 84 genes encoding putative WRKY TFs have been identified in two wild potato relatives, Solanum commersonii and S. chacoense. Phylogenetic analysis of WRKY proteins divided ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs into three Groups and seven subGroups. Structural and phylogenetic comparative analyses suggested an interspecific variability of WRKYs. Analysis of gene expression profiles in different tissues and under various stresses allowed to select ScWRKY045 as a good candidate in wounding-response, ScWRKY055 as a bacterial infection triggered WRKY and ScWRKY023 as a multiple stress-responsive WRKY gene. Those WRKYs were further studied through interactome analysis allowing the identification of potential co-expression relationships between ScWRKYs/SchWRKYs and genes of various pathways. Overall, this study enabled the discrimination of WRKY genes that could be considered as potential candidates in both breeding programs and functional studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants experience environmental constrains and pathogen attacks during their life. Being sessile organisms, their survival depends on the ability to properly and promptly reprogram cellular networks. Several and different classes of transcription factors (TFs) work as “master regulators” and “selector genes”, being able to control processes that specify cell types and developmental patterning and modulate specific pathways. Among them, WRKY factors are drawing a great deal of interest in the scientific community due to their ability to simultaneously cope with multiple stresses1,2. They are notorious for coordinating signals in plant immunity response against several pathogens and pest attacks3,4. More recently, it has been confirmed that WRKYs also base defence mechanism to abiotic stresses and play a key role in cross-talk pathway networks between plant response and development5,6. Their involvement into multiple stress response and in plant growth regulation is evidenced by their W-box specific DNA binding7,8. Besides, WRKY binds sugar responsive elements and, very recently, it has been demonstrated that they activate sugar responsive genes through an epigenetic mechanism of control9. The systematic classification of components of the WRKY family is well organized. It is based on the WRKY binding domain (WD) characteristics along with those of the Zinc Finger (ZF) motif, which is typically present downstream the WD. WD consists of 60 amino acids structured as four-stranded β-sheets able to enter the major groove of B-form DNA. The highly conserved motif is “WRKYGQK”. According to the number of WDs and the type of zinc finger motif, WRKY proteins can be classified into three Groups, namely Group I, II, and III: Group I WRKY members contain two WDs with two classical C2H2 ZF motifs, Group II WRKYs have one WD with one C2H2 ZF motif, and Group III WRKYs contain one WD with one C2HC ZF motif 3,5. Group II WRKYs can be divided into five subGroups (IIa-IIe)10. It is well recognized that Group I WRKY members are the evolutionary ancestors of the other WRKYs and that they exist only in lower plants11,12. The complexity of this gene family involves different molecular levels, from the transcriptional self-regulation through microRNAs to post-transcriptional events, such as alternative splicing, post-translational regulation through ubiquitin proteasome system and MAPK cascade9. Studies addressed to mine sequence divergences or to identify gene expression differences in WRKYs of cultivated and wild species are increasing. Such investigations may pave the way into exploiting these regulators for breeding purposes. A recent study carried out in the sweet potato wild ancestor Ipomoea trifida, highlighted how investigations on WRKY gene family in wild relatives can boost the molecular breeding of cultivated species13. However, our knowledge is still not complete and therefore WRKY gene biodiversity remains unlocked in many species.

The potato, Solanum tuberosum, is one of the most cultivated non-cereal crop in the world. Its cultivation is often hampered by the fact that it is susceptible to a wide range of stressors causing severe yield losses. Sources of resistance can be found in its tuber-bearing wild relatives, that are highly used as rootstock for cultivated Solanaceae14 but poorly used in breeding programs. However, recent technologies can be implemented to enhance this precious source of genes/alleles. Among them, genome sequences are opening new paths for both basic research and varietal development. Nowadays, the genome sequence of two wild potato species, S. commersonii and S. chacoense, are available15,16. These species are excellent sources of tolerance to both biotic stressors, such as Ralstonia solanacearum17, Phytophthora infestans18 and Pectobacterium carotovorum19, and abiotic constraints, such as cold15 and drought20. Despite this, to date no studies have examined WRKY gene family components and their different characteristics in wild potato species. A few data on this gene family are available only in the cultivated potato, where Zhang et al.21, Liu et al.22 and Cheng et al.12 identified 79, 82 and 81 StWRKYs, respectively. Previously, Dellagi et al.23 identified StWRKY1 as a good candidate for functional studies, and Shahzad et al.24 overexpressed it in potato. They provided evidence that StWRKY1 acts as positive regulator of biotic and abiotic stress resistance through the activation of basal defence networks. Here, for the first time, we report a detailed analysis of WRKY genes in the genome of S. commersonii and S. chacoense, providing subGroup classification, gene structure and conserved motif composition. We analysed the patterns of ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs expression in flowers, leaves and tubers to determine whether some WRKYs own tissue-specificity. Furthermore, we used S. commersonii to highlight expression changes of selected ScWRKY genes after wounding and biotic (Potato Virus Y and P. carotovorum) stresses. Through the data here presented, the work aims to give a picture of the potato wild WRKY members, their nature and the complexity of their responses to unfavourable situations.

Materials and Methods

Identification of WRKY in S. commersonii and S. chacoense and phylogenetic analysis

The well-known WRKY protein sequences of S. tuberosum22 and A. thaliana25 were used as queries to build an HMM profile through HMMER as reported by Esposito et al.26 and to search orthologs in S. commersonii (cmm1T clone of PI243503) and S. chacoense (M6 clone) genomes. Only sequences with an e-value lower than 10−5 and an identity higher than 55% were regarded as putative WRKYs and further analyzed. The full-lenght WRKY candidate proteins were then manually confirmed by checking the WRKY domain using the NCBI search domain online tool26 and used for the phylogenetic analysis. Names were assigned based on S. tuberosum orthologs using bootstrap replicates of the Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree (values higher than 50). Briefly, MEGAX27 was first used to establish the best-fit model of evolution through the option “Find best DNA/Protein Models” implemented in the program and then for phylogenetic tree building using the appropriate options. In the phylogenetic analysis were integrated seven AtWRKY proteins randomly selected as representative of each WRKY Group, as already reported by Karanja et al.28. One-to-one orthologs were considered when candidate proteins allocated on the same clade in the phylogenetic tree with S. tuberosum. The exon-intron organization of WRKY genes was determined using the online GSDS tool (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn). Finally, the on-line tool Phenogram (http://visualization.ritchielab.org/phenograms/plot) was used to determine the location of the WRKY genes on S. chacoense chromosomes.

Public RNAseq-based expression analysis

The transcriptional activity of WRKY genes related to three tissues (flower, leaf and tuber) in S. commersonii and S. chacoense was estimated using the publicly available RNAseq data sets. As far as S. commersonii is concerned, we used raw single-end fastq data deposited under study SRP050412. Briefly, to remove unwanted sequences originating from organelles, reads were mapped against the mitochondrial (S_tuberosum_Group_Phureja_ mitochondrion_DM1-3-516-R44) and chloroplast (S._tuberosum_Group_Phureja_chloroplast_DM1-3-516-R44) genomes using BOWTIE2 2.2.229 with sensitive local mapping. Unmapped reads were mapped against the S. commersonii genome. The BAM files were then analyzed using Cufflinks–Cuffquant software (version 2.2.1) to assemble the aligned reads and to access transcriptome complexity. Expression values for each gene were estimated based on RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) using the default options. No biological replicates were available for S. commersonii. As for S. chacoense, data were expressed as mean of biological replicates and RPKM values we directly retrieved from SpudDB (http://solanaceae.plantbiology.msu.edu). For all StWRKY orthologs we recovered from the public S. tuberosum database (http://solanaceae.plantbiology.msu.edu) transcriptional data regarding potato leaves subjected to salt stress (50 mM NaCl for 24 h), osmotic stress (260 μM mannitol for 24 h), heat stress (35 °C for 24 h) and treatments with 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) (10 µM for 24 h), abscisic acid (ABA) (50 µM for 24 h), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (10 µM for 24 h), gibberellic acid (GA3) (50 µM for 24 h), β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) (24, 48, 72 h), benzothiadiazole (BTH) (24, 48, 72 h), and invitro culture (root and shoot).

Plant materials and stress treatments

In-vitro plantlets of S. commersonii clone cmm1T, accession PI243503, derived from the Inter-Regional Potato Introduction Station (Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin), were micro-propagated as described by D’Amelia et al.30. Four-week-old vitroplants were transplanted into 14-mm plastic pots containing sterile soil and grown in a greenhouse under long-day conditions (16-h light, 8-h dark); temperature was set at 26 °C during the day and 18 °C at night. Three-week-old seedlings were used for all stress experiments and sampled in a 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 hpt (hours post treatment) time course. As for virus infection, young plants of clone cmm1T were mechanically inoculated with Potato Virus Y tuber necrotic strain (PVYNTN) as reported by Esposito et al.31. For assessing bacterial resistance, the protocol of Melito et al.32 was used with few modifications. The stem base of vitroplants (one injection per plant) was inoculated with 20 μl of P. carotovorum strain Ecc 009 sospension under greenhouse conditions (with temperatures ranging from 20 to 30 °C during the day and from 12 to 17 °C during the night). The bacterial culture was adjusted to 106 CFU·mL−1 in MgCl2 solution. The whole plant was then covered with a transparent plastic bag. For both treatments (viral and bacterial), plants inoculated with buffer were considered as mock control. At each time point, leaves were collected from three biological replicates, both for treated and untreated samples. Each biological replicate consisted of a pool of three plants. Young leaf samples were collected from treated and mock control plants following the time course and stored at − 80 °C before RNA extraction. Wounding stress was induced according to the protocol of Vannozzi et al.33 with few modifications. Leaf discs (15 mm diameter) were punched from healthy leaves detached from glasshouse-grown plantlets and incubated upside down on 3MM moist filter paper in large Petri dishes at 22 °C under 12 h light / 12 h dark conditions until harvest. Collected discs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction. Five discs were randomly chosen per each time point. No treated leaves were used as control. Each treatment consisted of three biological replications.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of grinded leaves as reported by Rinaldi et al.34 and Villano et al.35. The SpectrumTM Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol with some modifications. Quantity and quality of the isolated RNA was measured using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For cDNA synthesis, 1 µg of each RNA sample was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Specific primers were designed using the website Primer3 as reported by Koressaar et al.36 (Supplementary Table 1). Expression analysis was conducted by RT-qPCR as reported by Di Meo et al.37 and Brulè et al.38 using a SYBR Green method on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each 15 µL PCR reaction contained 330 nM of each primer, 2 µL of 5-fold diluted cDNA and 7.5 µL of SYBR Green Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The SDS 2.3 and RQ Manager 1.2 software (both Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used for data elaboration. The expression of each target gene was normalized with the expression level of the housekeeping gene (Elongation Factor) and calibrated with the mock control using the Livak method, obtaining the values in log2(FC)39. Each analysis consisted of three technical replications.

Protein-protein interaction in silico analyses

An interactome analysis was carried out to investigate the function of tissue-specific and stress responsive ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs selected in the expression study through the analysis of direct ortholog of StWRKY genes. The protein-protein interaction networks STRING database was used (http://string-db.org/). It reports protein associations based on various sources, such as experimental results, pathway understanding, text-mining and genomic information40. The interactome was constructed using a medium confidence score (0.400).

Results

Phylogenetic analysis and classification of ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs

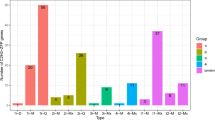

A total of 79 and 84 candidates corresponding to the Pfam WRKY family were distinguished in S. commersonii and S. chacoense, respectively (Table 1). Based on phylogenetic analysis, 71 ScWRKYs and 80 in SchWRKYs were identified as direct orthologs of StWRKYs, while the remaining were classified as not direct orthologs and named with the suffix -like. Two paralog genes of SchWRKY080, SchWRKY086 and ScWRKY087 were also identified and named with the suffix -a and -b (Table 1). The phylogenetic analysis of seven AtWRKY proteins randomly selected as representative of each WRKY Group and all S. commersonii and S. chacoense WRKY proteins revealed ScWRKY and SchWRKY classification in three large Groups corresponding to Group I, II and III (Fig. 1), with the exception of nine proteins in S. commersonii (ScWRKY047,ScWRKY051, ScWRKY052, ScWRKY055, ScWRKY085, ScWRKY087a, ScWRKY087b, ScWRKY088 and ScWRKY089) and eight proteins in S. chacoense (SchWRKY047, SchWRKY051, SchWRKY052, SchWRKY056, SchWRKY057, SchWRKY085, SchWRKY088 and SchWRKY089), that were not assigned to any Group (Table 1). In S. commersonii, 12 ScWRKY proteins belonged to Group I, 47 to Group II, and 10 to Group III. Group II proteins were further categorized into subGroups. Group IIa, IIb, IIc, IId and IIe included 5, 8, 13, 7 and 14 ScWRKYs respectively (Table 1). As far as S. chacoense is concerned, 14 proteins belonging to Group I, 45 to Group II, and 15 to Group III were identified. Those of Group II were classified in subGroup IIa (5 SchWRKYs), IIb (5), IIc (15), IId (7) and IIe (12) (Table 1). Gene and protein features, including the length of the protein sequence, the WRKY domain motif composition and the exons/introns number were analyzed and reported in Supplementary Table 2. In S. commersonii, the “WRKYGQK” pattern was highly conserved in 69 ScWRKYs, while five variations were observed in the other proteins (“WGKYGQK”, “WRWLKCG”, “WSKYGQK”, “WRKCGQK”, “WRKYGMK”). In S. chacoense, 74 SchWRKYs contained the “WRKYGQK” domain, while the other proteins contained one of the following variations: “WIKYGEN”, “WHKYGQK”, “WRKYGMK”, “WKKHGSN”, “WHKCGQK”. Concerning the Zinc Finger motif, the most common pattern in both species was “C-X4-5-7-C-X22-23-24-H-X-H/C”. The only exceptions were ScWRKY068 with “C-X8-C-X27-H-X2-H”, ScWRKY074 with “C-X1-C-X26-H-X-C”, and SchWRKY074 with “C-X8-C-X24-H-X-C”. Regarding the number of WDs in the studied proteins, out of 12 members belonging to Group I in S. commersonii, eight contained two WDs, two had two WDs and other two possessed three WDs. All Group I members in S. chacoense harbored two WDs, except SchWRKY014 (one WD). Seven ScWRKYs belonging to Group II and two of Group III contained two WDs, while all other members had only one WD. In S. chacoense, Group II and III proteins harbored one WD. All Group III members contained the HXC Zinc Finger domain (Supplementary Table 2). Our analysis pointed out that the number of amino acids of ScWRKYs varied from 107 (ScWRKY30) to 752 (ScWRKY87), and that of SchWRKYs from 123 (SchWRKY21) to 744 (SchWRKY3) (Supplementary Table 2). The exon-intron organization of our WRKY genes was examined to gain more insight into the evolution of the WRKY family in potato. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, all ScWRKY genes possessed from one to eight exons. A similar trend was observed in S. chacoense. Concerning the genomic localization of WRKY genes, due to the unavailability of S. commersonii physical map, we plotted genes only on S. chacoense chromosomes using the Phenogram on-line tool (http://visualization.ritchielab.org/phenograms/plot) (Figure S1). Out of 84 SchWRKY genes identified, 83 were mapped. As represented in Figure S1, most of the genes were located on chromosome 3 (11 genes; 13.1%), followed by chromosome 5 (10; 11.9%), Unknown (8; 9.5%) and 2 (7; 8.3%). A total of 25 SchWRKY genes (5 on each chromosome) were localized on chromosomes 7 to 12, whereas no one was mapped on chromosome 11.

Phylogenetic analysis WRKY proteins in S. commersonii, S. chacoense and seven representative proteins of Arabidopsis. Multiple sequence alignments of WRKY amino acid sequences were performed using ClustalX, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGAX by the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was divided into seven phylogenetic subGroups and distinguished by colours: dark purple for Group I, light blue for subGroup IIa, orange for subGroup IIb, light purple for subGroup IIc, dark blue for subGroup IId, green for subGroup IIe, red for Group III. The bootstrap values were ≥85%.

Expression patterns of WRKY genes in S. commersonii and S. chacoense

To explore the expression of WRKY genes, we analyzed and calculated the RNA sequence data available for leaf, flower and tuber in both species (Figs. 2a and 2b). The heat-map based expression profiles of ScWRKYs (Fig. 2a) and SchWRKYs (Fig. 2b) revealed their dynamic and differential expression in various tissues and that the range of expression varied among the two species. In S. commersonii, 21 (26.5%) ScWRKY genes (01, 14, 15-like, 15-like_2, 21, 30, 39, 58-like, 60, 61, 62, 62-like, 63, 66-like, 67, 81, 84_like, 85, 86, 88 and 89) showed very low or undetectable expression (FPKM values from 0 to 0.5) in all studied tissues, while 16 (20.2%) genes (18, 23, 03, 48, 87, 08, 11, 47, 79, 10, 51, 45, 05, 06, 12 and 49) were highly expressed (FPKM > 5) in all tissues. Some of the remaining genes showed tissue specificities. ScWRKY002, ScWRKY013 and ScWRKY017 were highly expressed only in flower, and ScWRKY042 and ScWRKY080 only in leaf, while no tuber specific ScWRKYs were identified. In S. chacoense, 21 (25%) SchWRKY genes (4, 14, 15, 16, 21, 34, 56, 57, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 67, 69, 81, 83, 86, 87a, 88 and 89) showed no expression in all considered tissues, while 42 (50%) were overexpressed in all tissues. Concerning the remaining genes, nine leaf-specific (SchWRKY001, SchWRKY017, SchWRKY024, SchWRKY027, SchWRKY043, SchWRKY059, SchWRKY073, SchWRKY077 and SchWRKY085) and three flower-specific genes (SchWRKY028, SchWRKY030 and SchWRKY087b) were identified. As is the case of S. commersonii, no tuber specific SchWRKYs were found.

(a) Expression profile analysis of ScWRKYs genes in different tissues. Transcriptome data (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads; RPKM) were used to measure the expression levels of ScWRKY genes in leaves, tubers and flowers. The colored scale for the different expression levels is shown. b) Expression profile analysis of SchWRKYs genes in different tissues. Transcriptome data (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads; RPKM) were used to measure the expression levels of SchWRKY genes in leaves, tubers and flowers. The colored scale for the different expression levels is shown.

Four ScWRKY genes (ScWRKY016, ScWRKY023, ScWRKY045 and ScWRKY055) distributed in different Groups were selected to further investigate WRKYs behaviour in response to biotic (wounding) and abiotic (PVY and P. carotovorum) stressors using qRT-PCR (Fig. 3). The expression trend of our WRKYs was variable among and during treatments. In particular, wounding stress caused ScWRKY023 and ScWRKY045 overexpression during the whole treatment and ScWRKY055 overexpression at 4- and 6-hours post treatment (hpt). As for viral infection response, ScWRKY016 and ScWRKY045 were always downregulated, while the other genes were upregulated only at one of the five hpt. The bacterial inoculation with P. carotovorum did not activate ScWRKY016 and ScWRKY045, while the other two genes were upregulated at 2- and 6- hpt. Given the involvement of WRKYs in several biological processes, we wondered whether they might play roles under other stresses. Since WRKY expression data on wild potato species exposed to any stress are not available, we retrieved WRKYs RPKM values from S. tuberosum experiments involving several treatments and stressors. As shown in Figure S2, the transcription of most WRKY genes was affected by various treatments. Only StWRKY61 to StWRKY67 did not change their transcriptional activity upon stress. The late blight infection did not perturbate the expression of StWRKYs. StWRKY023, StWRKY044, StWRKY054 and StWRKY055 increased their expression following mannitol treatment, whereas ABA, IAA and GA3 hormonal treatments affected the transcriptional activity of 3 (StWRKY027, StWRKY028 and StWRKY046), 1 (StWRKY035) and 4 (StWRKY023, StWRKY054, StWRKY068, StWRKY070) S. tuberosum WRKYs, respectively. BABA and BTH treatments induced an overexpression of 18 and 15 StWRKYs respectively, of which StWRKY042, StWRKY075, StWRKY078 and StWRKY080 were in common. Concerning heat stress, 12 StWRKYs were overexpressed. Finally, under in-vitro culture conditions, 10 StWRKYs were overexpressed in shoots and one (StWRKY004) in roots.

Expression RT-qPCR analysis of selected ScWRKY genes under abiotic and biotic stresses: wounding, PVY and P. carotovorum. For each stress the same time course of 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 hours post treatment was considered. The y-axes represent the mean relative expression normalized against non-treated plants for wounding stress and water-treated plants for PVY and P. carotovorum inoculations. Standard deviation values are shown.

In silico protein interaction network of selected ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs

A network of interaction was studied for WRKYs showing either tissue-specific or stress-induced expression (Figure S3a and S3b). The S. commersonii flower-specific expressed WRKY002 formed a node with the anthocyanins and cell differentiation regulatory proteins. STRING analyses provided evidence that ScWRKY002 interacts, among the others, with JAF13 and TTG1, two well-characterized potato anthocyanins bHLH and WD40 TFs27,39. Both the leaf-specific expressed ScWRKY042 and ScWRKY080 formed a cluster of interaction with a Leucine Rich Repeat (LRR) protein (an evolutionarily conserved protein associated with innate immunity in plants). The two wounding-responsive ScWRKY023 and ScWRKY045 established two independent nodes of interaction. The former set a cluster with “Wound-responsive Apetala2 like factor 2 (WRAF2)” (annotation for transcript PGSC0003DMT400021314 on SpudDB database), while ScWRKY045 interacted with a cluster of proteins linked to a class of glycosyltransferase. Concerning S. chacoense, SchWRKY030 (found to be flower-specific) interacted directly with eIF2B_5, a key protein involved in mRNA translation mechanisms. On the counterpart, the leaf-specific SchWRKY017, SchWRKY043, SchWRKY059 and SchWRKY077, together with the flower-specific SchWRKY028, showed the same interaction with LRR proteins already described for ScWRKY042 and ScWRKY080.

Discussion

Due to its importance in the regulation of several processes in plants5, WRKY family has been studied in more than 60 plant species. In Solanaceae, data are available in some important crops, such as S. tuberosum (7921, 8222 and 8112 WRKYs), S. lycopersicum (83 WRKYs41) and S. melongena (50 WRKYs42). However, no information is available on the number and structural variability of WRKY TFs in Solanaceae wild species, which represent an important reservoir of genetic variation for breeding. This study was set up with the aim to profile WRKY encoding genes in S. commersonii and S. chacoense, two noteworthy tuber-bearing potato species used in potato breeding programs20,43,44,45.

Structural analysis of ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs revealed interspecific diversification

The recently published genome annotation of S. commersonii15 and S. chacoense16 enables a comprehensive investigation of the WRKY family. We detected 79 and 84 genes encoding putative WRKY TFs in S. commersonii and S. chacoense, respectively. These results indicate that, compared to the cultivated potato22, S. commersonii possesses a lower number and S. chacoense a higher number of WRKY genes. Both species displayed a number of WRKYs greater than that of barley (45)46, castor bean (58)47, cucumber (55)48, rapeseed (43)49 and grapevine (59)50, and lower than that of cotton (120)51, maize (136)52, soybean (131)53 and rice (100)25. From this comparison, it appears that the number of WRKY encoding genes is not proportional to the genome size of the respective plant species, as also reported by Waqas et al.54. ScWRKY and SchWRKY proteins were primarily divided into three main phylogenetic Groups with Group II further classified into five subGroups (IIa-IIe). Most of WRKYs found in the two wild species belonged to Group II and this is in line with results obtained in S. tuberosum22. As known, WRKY proteins are characterized by one or more WRKY domain. In this study, we found that ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs had either one or two WDs. Interestingly, two ScWRKYs (ScWRKY010 and ScWRKY002) carried three WDs. This might be the result of the acquisition of a WRKY domain during evolution, supporting findings of Aversano et al.15 and Esposito et al.31,55, who reported that S. commersonii prosper lineage-specific segmental duplications during evolution. Not only WDs number, but also WDs structural divergences identified in S. commersonii and S. chacoense might be the consequence of mutations during the process of evolution. Almost all ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs contained the highly conserved heptapeptide WRKYGQK motif, except for eight variants. Among them, WGKYGQK of ScWRKY014, WRWLKCG of ScWRKY061, WHKYGQK of SchWRKY014 and WKKHGSN in SchWRKY057 were not found in any other species. On the counterpart, the remaining variants were identified also in S. tuberosum22, S. lycopersicum56, H. vulgare57 and C. annum58. Zhou et al.59 hypothesized that these variations may change the DNA targets’ binding specificity. The structural diversity has been investigated also at the genomic level through the identification of exons and introns. As reported by Shiu and Bleecker60, this can highlight events of diversification and neo-functionalization of WRKY genes. In contrast to findings by Wang et al.61, our results did not reveal a conservation of gene structure among the members of the same Group, even though they allowed the discrimination of eight intron-lacking WRKYs (two ScWRKYs and six SchWRKYs). This is in agreement with results reported in the cultivated potato, where StWRKY23 and StWRKY24 had no introns21. Lynch et al.62 hypothesized that the intron turnover can be the result of reverse transcription of the mature mRNA followed by homologous recombination with intron-containing alleles.

Identification of tissue-specific and stress responsive WRKYs in wild potatoes

WRKY TFs have been found to play important roles under abiotic stresses, such as drought8, heat63, wounding50, and biotic constraints, such as bacteria59 and viruses64. Tissue-specificity of WRKY genes has also been highlighted in different crops, such as pepper58, cotton65 and soybean66, elucidating their role in developmental and functional processes. Our study investigated for the first time the stress response and tissue-specificity of WRKY genes in two wild potato species. Six and 11 WRKY genes were identified as flower- and leaf-specific, respectively. Zhang and collaborators21 considered that the known protein-protein interaction network can provide important clues to better understand gene expression regulation. Basing on this, we investigated the interactome of tissue-specific and stress-responsive WRKYs identified here and found potential co-expression relationships between ScWRKYs/SchWRKYs and genes of various pathways. From our analyses, interesting observations and different clues for future functional studies have emerged. For example, ScWRKY002 could be in some way involved in anthocyanin activation in flowers of S. commersonii: it interacts with anthocyanin bHLHs and the flower of this wild species strongly accumulates anthocyanins14,67. Previous studies reported that some WRKYs can be involved in the coordination of multiple biological processes. For example, AtWRKY33 regulates disease resistance, NaCl tolerance and thermotolerance68,69,70, while GhWRKY40 modulates tolerance to wounding stress and resistance to R. solanacearum43. This suggests that some WRKY proteins provide important nodes of crosstalk between different physiological processes. However, the putative members of WRKY family and their possible roles in signalling crosstalk are still barely known. To the authors’ best knowledge, no expression data are available on ScWRKYs and SchWRKYs; by contrast, StWRKYs have previously received attention. Among them, only Shahzad et al.71 and Yogendra et al.72 found StWRKY010 (PGSC0003DMP400029302) and StWRKY020 (PGSC0003DMP400028763) to be active in P. infestans-potato interaction. Consistently with these data, our results indicated that the same genes increased their expression after BABA treatment, known to confer protection against several biotic threats. Furthermore, we focused our attention on a group of proteins (ScWRKY016, ScWRKY023, ScWRKY045 and ScWRKY055) which were reported to be stress-responsive21,73. For these genes, we tested the transcriptional activity of wild S. commersonii alleles after wounding and bacterial infection and investigated on their direct orthologs expression following various treatments. Among them, StWRKY016, StWRKY045 and StWRKY055 appeared to be required by plants to face damages by heat stress, while StWRKY023 was reported to be active under mannitol and GA3 treatments as well as drought stress73. Our results suggested that the wild alleles of ScWRKY023 and ScWRKY045 might represent promising candidates for multiple stress responses as they are leaf-specific and constantly expressed after wounding in S. commersonii but not in the cultivated potato. In addition, WRKY023 is also induced by bacterial infection and it is suggested to interact with both a WRAF2-like protein and with the LRR mediated immunity system74,75.

Conclusions

The present study identified 79 and 84 genes encoding putative WRKY TFs in S. commersonii and S. chacoense, respectively. Their protein structure and data from the comparative analyses suggested an interspecific variability of WRKY genes. Most of them were up-regulated under stress conditions and across different tissues, hinting a possible role in the cross-talk between plant and environmental cues in potato species. Taken as hole, these analyses will help to hasten the determination of the function of WRKY TFs especially in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Candidate ScWRKY and SchWRKY genes identified here can be employed in potato breeding programs.

References

Phukan, U. J., Jeena, G. S. & Shukla, R. K. WRKY transcription factors: molecular regulation and stress responses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 760 (2016).

Bai, Y., Sunarti, S., Kissoudis, C., Visser, R. G. F. & Van Der Linden, G. The role of tomato WRKY genes in plant responses to combined abiotic and biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 801 (2018).

Eulgem, T. & Somssich, I. E. Networks of WRKY transcription factors in defense signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10(4), 366–371 (2007).

Koornneef, A. & Pieterse, C. M. Cross talk in defense signaling. Plant Physiol. 146(3), 839–844 (2008).

Rushton, P. J., Somssich, I. E., Ringler, P. & Shen, Q. J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15(5), 247–258 (2010).

Chen, J. & Yin, Y. WRKY transcription factors are involved in brassinosteroid signaling and mediate the crosstalk between plant growth and drought tolerance. Plant Signal. Behav. 12(11), e1365212 (2017).

Dhatterwal, P., Basu, S., Mehrotra, S. & Mehrotra, R. Genome wide analysis of W-box element in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals TGAC motif with genes down regulated by heat and salinity. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 1681 (2019).

Liu, L., Xu, W., Hu, X., Liu, H. & Lin, Y. W-box and G-box elements play important roles in early senescence of rice flag leaf. Sci. Rep. 6, 20881 (2016).

Chen, X., Li, C., Wang, H. & Guo, Z. WRKY transcription factors: evolution binding and action. Phytopath. Res. 1(1), 13 (2019).

Eulgem, T., Rushton, P. J., Robatzek, S. & Somssich, I. E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 5(5), 199–206 (2000).

Zhang, Y. & Wang, L. The WRKY transcription factor superfamily: its origin in eukaryotes and expansion in plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 5(1), 1 (2005).

Cheng, Y., Ahammed, G. J., Li, Z. & Wan, H. Comparative genomic analysis reveals extensive genetic and functional variations of WRKYs in Solanaceae. Front. Genet. 10, 492 (2019).

Li, M. et al. The wild sweetpotato (Ipomoea trifida) genome provides insights into storage root development. BMC Plant Biol. 19(1), 119 (2019).

Musarella, C. M. Solanum torvum Sw. (Solanaceae): a new alien species for. Europe. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1, 8 (2019).

Aversano, R. et al. The Solanum commersonii genome sequence provides insights into adaptation to stress conditions and genome evolution of wild potato relatives. Plant Cell 27(4), 954–968 (2015).

Leisner, C. P. et al. Genome sequence of M6 a diploid inbred clone of the high‐glycoalkaloid‐producing tuber‐bearing potato species Solanum chacoense reveals residual heterozygosity. Plant J. 94(3), 562–570 (2018).

Puigvert, M. et al. Transcriptomes of Ralstonia solanacearum during root colonization of Solanum commersonii. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 370 (2017).

Micheletto, S., Boland, R. & Huarte, M. Argentinian wild diploid Solanum species as sources of quantitative late blight resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101, 902–906 (2000).

Chung, Y. S. & Jansky, S. Considerations for selecting disease resistant wild germplasm (Solanum spp): lessons from a case study of resistance to bacterial soft rot and Colorado potato beetle Genet. Resour. Crop Ev. 65(8), 2287–2292 (2018).

Jansky, S., Haynes, K. & Douches, D. Comparison of two strategies to introgress genes for resistance to common scab from diploid Solanum chacoense into tetraploid cultivated potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 96(3), 255–261 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Genome-wide identification of the potato WRKY transcription factor family. PloS one 12(7), e0181573 (2017).

Liu, Q. N. et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the WRKY gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 71, 212–218 (2017).

Dellagi, A. et al. A potato gene encoding a WRKY-like transcription factor is induced in interactions with Erwinia carotovora subsp atroseptica and Phytophthora infestans and is coregulated with class I endochitinase expression. Mol. Plant Microbe In. 13(10), 1092–1101 (2000).

Shahzad, R. et al. Overexpression of potato transcription factor (StWRKY1) conferred resistance to Phytophthora infestans and improved tolerance to water stress. Plant Omics 9(2), 149 (2016).

Wu, K. L., Guo, Z. J., Wang, H. H. & Li, J. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and Arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Res. 12(1), 9–26 (2005).

Esposito, S., D'amelia, V., Carputo, D. & Aversano, R. Genes involved in stress signals: the CBLs-CIPKs network in cold tolerant Solanum commersonii. Biologia plantarum 63, 699–709 (2019).

Hall, B. G. Building phylogenetic trees from molecular data with MEGA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30(5), 1229–1235 (2013).

Karanja, B. K. et al. Genome-wide characterization of the WRKY gene family in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) reveals its critical functions under different abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 36(11), 1757–1773 (2017).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9(4), 357 (2012).

D’Amelia, V. et al. High AN1 variability and interaction with basic helix‐loop‐helix co‐factors related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in potato leaves. Plant J. 80(3), 527–540 (2014).

Esposito, S. et al. Dicer-like and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene family identification and annotation in the cultivated Solanum tuberosum and its wild relative S. commersonii. Planta 248(3), 729–743 (2018).

Melito, S., Garramone, R., Villano, C. & Carputo, D. Chipping ability specific gravity and resistance to Pectobacterium carotovorum in advanced potato selections. New Zeal. J. Crop Hort. 45(2), 81–90 (2017).

Vannozzi, A., Dry, I. B., Fasoli, M., Zenoni, S. & Lucchin, M. Genome-wide analysis of the grapevine stilbene synthase multigenic family: genomic organization and expression profiles upon biotic and abiotic stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 12(1), 130 (2012).

Rinaldi, A. et al. Metabolic and RNA profiling elucidates proanthocyanidins accumulation in Aglianico grape. Food Chem. 231, 52–59 (2017).

Villano, C. et al. Polyphenol content and differential expression of flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes in berries of Aglianico. Acta Hortic. 1188, 141–148 (2017).

Koressaar, T. et al. Primer3_masker: integrating masking of template sequence with primer design software. Bioinformatics 34(11), 1937–1938 (2018).

Di Meo, F. et al. Anti-cancer activity of grape seed semi-polar extracts in human mesothelioma cell lines. J. Funct. Foods 61, 103515 (2019).

Brulé, D. et al. The grapevine (Vitis vinifera) LysM receptor kinases VvLYK1‐1 and VvLYK1‐2 mediate chitooligosaccharide‐triggered immunity. Plant Biotech. J. 17(4), 812–825 (2019).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 25(4), 402–408 (2001).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(D1), D447–D452 (2014).

Karkute, S. G. et al. Genome wide expression analysis of WRKY genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under drought stress. Plant. Gene 13, 8–17 (2018).

Yang, X. et al. The WRKY transcription factor genes in eggplant (Solanum melongena L) and Turkey Berry (Solanum torvum Sw). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16(4), 7608–7626 (2015).

Carputo, D. et al. Resistance to frost and tuber soft rot in near-pentaploid Solanum tuberoum-S. commersonii hybrids. Breed Sci. 57, 145–151 (2007).

Carputo, D., Aversano, R. & Frusciante, L. Breeding potato for quality traits. Acta Hortic. 684, 55–64 (2015).

Villano, C., Miraglia, V., Iorizzo, M., Aversano, R. & Carputo, D. Combined use of molecular markers and high-resolution melting (HRM) to assess chromosome dosage in potato hybrids. J. Hered. 107(2), 187–192 (2015).

Mangelsen, E. et al. Phylogenetic and comparative gene expression analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare) WRKY transcription factor family reveals putatively retained functions between monocots and dicots. BMC Genom. 9, 194 (2008).

Zou, Z. et al. Gene structures evolution and transcriptional profiling of the WRKY gene family in castor bean (Ricinus communis L). PLoS One 11(2), e0148243 (2016).

Ling, J. et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY gene family in Cucumis sativus. BMC Gen. 12(1), 471 (2011).

Yang, B., Jiang, Y., Rahman, M. H., Deyholos, M. K. & Kav, N. N. Identification and expression analysis of WRKY transcription factor genes in canola (Brassica napus L) in response to fungal pathogens and hormone treatments. BMC Plant Biol. 9(1), 68 (2009).

Wang, M. et al. Genome and transcriptome analysis of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) WRKY gene family. Hort Res. 1, 14016 (2014).

Cai, C. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY transcription factor gene family in Gossypium raimondii and the expression of orthologs in cultivated tetraploid cotton. Crop J. 2(2-3), 87–101 (2014).

Wei, K. F., Chen, J., Chen, Y. F., Wu, L. J. & Xie, D. X. Molecular phylogenetic and expression analysis of the complete WRKY transcription factor family in maize. DNA Res. 19(2), 153–164 (2012).

Yu, Y., Wang, N., Hu, R. & Xiang, F. Genome-wide identification of soybean WRKY transcription factors in response to salt stress. Springerplus 5(1), 920 (2016).

Waqas, M. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of WRKY transcription factor family members from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) reveal their role in abiotic stress-responses. Genes Genom. 41(4), 467–481 (2019).

Esposito, S., et al. Deep‐sequencing of Solanum commersonii small RNA libraries reveals riboregulators involved in cold stress response. Plant Biol. (2018).

Huang, S. et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 287(6), 495–513 (2012).

Pandey, B., Grover, A. & Sharma, P. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed structural differences among WRKY domain-DNA interaction in barley (Hordeum vulgare). BMC Gen. 19(1), 132 (2018).

Cheng, Y. et al. Putative WRKYs associated with regulation of fruit ripening revealed by detailed expression analysis of the WRKY gene family in pepper. Sci Rep. 6, 39000 (2016).

Zhou, Q. Y. et al. Soybean WRKY‐type transcription factor genes GmWRKY13 GmWRKY21 and GmWRKY54 confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotech. J. 6(5), 486–503 (2008).

Shiu, S. H. & Bleecker, A. B. Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132(2), 530–543 (2003).

Wang, P. et al. Genome-wide identification of WRKY family genes and their response to abiotic stresses in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Genes Genom. 41(1), 17–33 (2019).

Lynch, M. Intron evolution as a population-genetic process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99(9), 6118–6123 (2002).

Gupta, S., Mishra, V. K., Kumari, S., Chand, R. & Varadwaj, P. K. Deciphering genome-wide WRKY gene family of Triticum aestivum L and their functional role in response to abiotic stress. Genes Genom. 41(1), 79–94 (2019).

Wang, G. et al. RNA-seq analysis of Brachypodium distachyon responses to Barley stripe mosaic virus infection. Crop J. 5(1), 1–10 (2017).

Gu, L. et al. Identification of the group IIa WRKY subfamily and the functional analysis of GhWRKY17 in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L). PloS one 13(1), e0191681 (2018).

Mohanta, T. K., Park, Y. H. & Bae, H. Novel genomic and evolutionary insight of WRKY transcription factors in plant lineage. Sci Rep 6, 37309 (2016).

D’Amelia, V., Aversano, R., Chiaiese, P. & Carputo, D. The antioxidant properties of plant flavonoids: their exploitation by molecular plant breeding. Phytochem Rev. 17(3), 611–625 (2018).

Jiang, J. et al. WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59(2), 86–101 (2017).

Birkenbihl, R. P., Diezel, C. & Somssich, I. E. Arabidopsis WRKY33 is a key transcriptional regulator of hormonal and metabolic responses toward Botrytis cinerea infection. Plant Phys. 159(1), 266–285 (2012).

Li, S., Fu, Q., Chen, L., Huang, W. & Yu, D. Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY25 WRKY26 and WRKY33 coordinate induction of plant thermotolerance. Planta 233(6), 1237–1252 (2011).

Shahzad, R. et al. Overexpression of potato transcription factor (Stwrky1) conferred resistance to Phytophthora infestans and improved tolerance to water stress. Plant Omics 9, 149–158 (2016).

Yogendra, K. N. et al. StWRKY8 transcription factor regulates benzylisoquinoline alkaloid pathway in potato conferring resistance to late blight. Plant Sci. 256, 206–216 (2016).

Gong, L., et al. Transcriptome profiling of the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) plant under drought stress and water-stimulus conditions. PLoS One 10(5) (2015).

Sasaki, K. et al. Two novel AP2/ERF domain proteins interact with cis‐element VWRE for wound‐induced expression of the Tobacco tpoxN1 gene. Plant J. 50(6), 1079–1092 (2007).

Heyman, J., Canher, B., Bisht, A., Christiaens, F. & De Veylder, L. Emerging role of the plant ERF transcription factors in coordinating wound defense responses and repair. J. Cell Sci. 131(2), jcs208215 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out within the project “Development of potato genetic resources for sustainable agriculture” (PORES) funded by the University of Naples Federico II (Project ID: E76J17000010001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C. and E.S. performed the analyses, processed the experimental data, interpreted the results and contributed to figure designing and manuscript writing. G.R., A.D. and Z.A. conducted experiments. V.D. provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. A.R. and C.D. conceived the idea of study, coordinated the work and contributed to results interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villano, C., Esposito, S., D’Amelia, V. et al. WRKY genes family study reveals tissue-specific and stress-responsive TFs in wild potato species. Sci Rep 10, 7196 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63823-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63823-w

This article is cited by

-

Distinct structural variants and repeat landscape shape the genomes of the ancient grapes Aglianico and Falanghina

BMC Plant Biology (2024)

-

WRKY transcription factors: evolution, regulation, and functional diversity in plants

Protoplasma (2023)

-

Whole-genome resequencing reveals genomic footprints of Italian sweet and hot pepper heirlooms giving insight into genes underlying key agronomic and qualitative traits

BMC Genomic Data (2022)

-

WRKY transcription factors: a promising way to deal with arsenic stress in rice

Molecular Biology Reports (2022)

-

Transcriptome and metabolome profiling in different stages of infestation of Eucalyptus urophylla clones by Ralstonia solanacearum

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.