Abstract

The esophageal gland duct may serve as a pathway for the spread of early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia (ESCN) to a deeper layer. Deep intraductal tumor spreading cannot be completely eradicated by ablation therapy. However, the risk factors of ductal involvement (DI) in patients with ESCNs have yet to be investigated. We consecutively enrolled 160 early ESCNs, which were treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection. The resected specimens were reviewed for the number, morphology, resected margin, distribution and extension level of DI, which were then correlated to clinical factors. A total of 317 DIs (median:3, range 1–40 per-lesion) in 61 lesions (38.1%) were identified. Of these lesions, 14 have DIs maximally extended to the level of lamina propria mucosa, 17 to muscularis mucosae, and 30 to the submucosa. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that tumors located in the upper esophagus (OR = 2.93, 95% CI, 1.02–8.42), large tumor circumferential extension (OR = 5.39, 95% CI, 1.06–27.47), deep tumor invasion depth (OR = 4.12, 95% CI, 1.81–9.33) and numerous Lugol-voiding lesions in background esophageal mucosa (OR = 2.65, 95% CI, 1.10–6.37) were risk factors for DI. The maximally extended level of ducts involved were significantly correlated with the cancer invasion depth (P < 0.05). Notably, 245 (77%) of the involved ducts were located at the central-trisection of the lesions, and 52% of them (165/317) revealed dilatation of esophageal glandular ducts. Five (1.6%) of the involved ducts revealed cancer cell invasion through the glandular structures. In conclusion, DI is not uncommon in early ESCN and may be a major limitation of endoscopic ablation therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth leading cause of death from cancer globally. Its incidence is rapidly increasing, however survival is still very poor1,2. An early diagnosis and prompt treatment are of paramount importance to improve survival and decrease disease burden. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has become the standard curative treatment for early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia (ESCN), including superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN)3,4,5,6. Several studies from Japan have reported good efficacy with ESD in long-term treatment outcomes4,5,6. Recently, endoscopic ablation modalities, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), or cryoballoon ablation, are both rapidly evolving, and some studies have shown the good efficacy and safety in treating the early ESCNs7,8,9,10. However, a higher recurrent risk (~20%) after ablation therapy has been reported11.

The submucosal glands of esophagus are generally scattered all over esophagus. These glands secrete acid mucin via the esophageal ducts which are lined by a single layer of cuboidal epithelium and open into the esophageal lumen12. In cases with early ESCN, the ducts of submucosal gland may serve as a path for tumor to spread to a deeper layer, so-called ductal involvement (DI)11,12,13. Because the maximal ablation depth of RFA in esophagus is the muscularis mucosae layer14, the deep intraductal tumor spreading could not be completely eradicated, which may potentially lead to tumor recurrence or even buried cancer. However, the risk factors and pathological features of DI in patients with early ESCNs has not been reported. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the clinical predictors and pathological characteristics of DI with the aim of guiding management and choosing the most appropriate endoscopic modality.

Methods

Patients and design

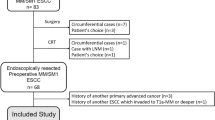

From July 2008 to December 2015, we consecutively enrolled patients with early ESCN, including HGIN and superficial ESCC, who received ESD at E-Da Hospital. A complete medical history was obtained before the endoscopic treatment, including demographic and clinical data. Thorough endoscopic examinations using narrow band imaging and Lugol chromoendoscopy (1.5%) were performed for each patient to define the lesions15. Based on the number and multiform pattern of Lugol-voiding lesions (LVLs) in the background esophageal mucosa, the patients were initially classified into four groups16: (A) no LVLs; (B) several (≤10) small LVLs; (C) many (>10) small LVLs; and (D) many (>10) irregular-shaped multiform LVLs. All patients underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and computed tomography (CT) to confirm that there was no lymph node or distant metastasis. Positron emission tomography (PET) was arranged in cases with biopsy-confirmed squamous cancers or those with HGIN but questionable regional lymph node detected by EUS or CT. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of E-Da Hospital and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

The ESD procedure was performed as described in our previous report3. Briefly, a circumferential incision was made initially, followed by a submucosal dissection with an IT-knife, IT-knife 2, or IT-knife nano (Olympus Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After or during the ESD procedure, adverse events including massive bleeding, emphysema, perforation and stricture were recorded. One-piece resection was defined as en bloc resection. R0 resection was considered to have a tumor-free margin when vertical and horizontal margins were free of tumor cells.

Histopathological examinations of the resected specimens

The resected specimens were fixed in formalin, cut into 2-mm slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The tumor size, depth of invasion, resection margins, lymphovascular invasion were histopathologically examined. The depth of invasion was subclassified as HGIN/intraepithelial cancer (m1), cancer invading the lamina propria (m2), muscularis mucosae (m3), superficial portion of the submucosa (≦200 μm, sm1), and deep submucosa (>sm1). Furthermore, two experienced doctors who were blinded to clinical history, retrospectively reviewed the presence of esophageal glandular DI (intraductal tumor spread), which was defined as the presence of ductal cancerization accompanied by non-neoplastic ductal epithelium lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells12,13, or complete replacement of normal ductal epithelium by carcinomatous squamous epithelial cells with the lumen filled with carcinomatous cells adjacent to normal submucosal glands and/or their ducts (Fig. 1). The number, morphology, margin and the maximal extension level in depth of the involved ducts were assessed. To evaluate the distribution of the involved ducts in the whole lesion, we further divided the specimens into “trisections” (Fig. 1D), and the locations of all involved ducts were recorded.

Histopathological examinations and characteristics of esophageal glandular ductal involvement (DI). (A) A case of intra-mucosal cancer with DI extending to the level of the submucosal layer (40x magnification); (B) The DI revealed the presence of ductal cancerization adjacent to normal submucosal glands (100x magnification); (C) A representative case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia with DI to the submucosal gland; (D) A case with many involved ducts. The slide of the specimen was divided into trisections. Of note, most of the involved ducts were located at the central part (arrow); (E) The DI revealed the presence of ductal cancerization accompanied by non-neoplastic ductal epithelium lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells and associated with subsequent esophageal ductal dilatation; (F) A case of DI in which the cancer cells invaded through the ductal structure (arrow). The area of invasion in higher magnification was shown in the inset.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS for Windows, version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Comparisons between groups (DI-positive vs. DI-negative) were carried out using the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or t-test, as appropriate. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the predictors of the presence of DI. Correlations between values were evaluated using non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation. Significance was set at a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

A total of 160 early-stage esophageal squamous neoplasias were treated with ESD. After the ESD procedures, 156 (97.5%) achieved en-bloc resection, and 153 had R0 resection (95.6%). Four patients had major procedure-related complications, including two with perforations and two with major bleeding and failed endoscopic hemostasis. All of whom received further esophagectomy and were discharged without sequela. Twenty-five patients developed post-ESD esophageal stenosis, and required balloon-dilatation to resolve the symptoms (median: 5, range: 1–80 sessions).

Histopathological assessment of the post-ESD specimens

The pathological analysis of the 160 resected specimens showed that 71 (44%) lesions were HGIN and 89 (56%) were SCC (43 reaching the depths of lamina propria mucosa, 19 to the muscularis mucosae, 22 to superficial submucosa and 5 to deep submucosa). Ten lesions (6%) with lymphovascular invasion (LVI) developed in the patients with SCC (4 m3, 2 sm1 and 4 > sm1). Sixty-one (38.1%) lesions had esophageal glandular DI, of which 14 maximally extended to the level of the lamina propria mucosa, 17 to the muscularis mucosae, and 30 to the submucosal layer (Fig. 1B,C).

Clinical predictors for the presence of esophageal DIs

The demographic and endoscopic characteristics of the patients with or without esophageal glandular DI are shown in Table 1. In univariate analysis, lesions with DI tended to be located in the upper esophagus, have invasive histology, larger tumor size, nodular surface, and larger circumferential extension. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that tumors located in the upper esophagus (OR = 2.93, 95% CI, 1.02–8.42), large tumor circumferential extension (OR = 5.39, 95% CI, 1.06–27.47), pre-treatment histology with SCC (OR = 4.12, 95% CI, 1.81–9.33) and numerous LVLs in background esophageal mucosa (OR = 2.65, 95% CI, 1.10–6.37) were predictors of esophageal DI (Table 2). Of note, among the patients with total circumferential lesions (n = 9), all had DI extending to the muscularis mucosae (n = 3) or submucosal layer (n = 6).

Characteristics of esophageal glandular DI

The relationships between tumor invasion depth and deepest extension level of esophageal glandular DI are shown in Table 3. Of note, among the 71 HGINs, 15 (21.1%) had DI and 11 (15.5%) extended deeper than the muscularis mucosae layer. The deepest extension level of DI was significantly correlated with the depth of cancer invasion (Spearman’s r = 0.373, P < 0.001).

Among the 61 ESCNs with DI, a total of 317 ducts (median: 3, range: 1–40 per lesion) were identified by a detailed histopathological review. Forty-eight (79%) neoplasias had more than one involved duct. The number of involved ducts was correlated with the cancer invasion depth (Spearman’s r = 0.314, P = 0.014) and tumor circumferential extension (Spearman’s r = 0.353, P = 0.005) (Fig. 2). Of note, 245 (77%) of the involved ducts were located at the central-trisection of the lesions (Fig. 1D), and 52% of them (165/317) revealed dilatation of esophageal glandular ducts (Fig. 1E). Five (1.6%) of the involved ducts revealed cancer cell invasion through the glandular structures (Fig. 1F). Three lesions showed that the resected margins were not free of involvement.

Discussion

Endoscopic therapies, including the endoscopic resection or endoscopic ablation, had gradually become the standard treatment for early ESCNs. However, whether the presence of DIs may influence the decision making in choosing treatment modalities needs to be investigated. In this study, we found that DI was not uncommon in the patients with early ESCN (38.1%), and of these patients 79% had more than one involved duct. ESCNs located in the upper esophagus, those with larger tumor circumferential extension, tumor invasion depth and Lugol-staining patterns were associated with the presence of esophageal DI. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to clarify the clinical predictors of DI in early ESCNs. The clinical implication of these findings is that they may guide treatment decision making and the surveillance program.

Intraductal spread is hypothesized as a path for tumor spread to a deeper layer11,12,13. However, most endoscopists have not paid a great deal of attention to the phenomenon, and only one previous study involving 201 surgically resected superficial ESCCs evaluated the clinical significance of DI13. In that study, among 83 lesions with mucosal carcinomas, DI occurred in 11 (13.8%), and six (7.2%) had DI extending to the submucosal layer. These involved ducts always remained in situ, and the carcinoma did not spread via stromal invasion, nor was there any lymph node metastasis or impact on survival. Subsequently, in that study, the authors concluded that DI is of little significance in patients with ESCC who receive surgery. However, now that endoscopic treatment is widely applied, DI may carry significant implications on the outcomes of patients treated endoscopically. In the current study, we found that the risk of cancer cell invasion through ductal structures was very low (1.6%). When choosing ESD as initial treatment, if the esophageal glands were not totally resected, it would be difficult to evaluate whether the margin of DI was tumor free. Thus, to decrease rates of incomplete resection and recurrence, clinicians should strive to remove the esophageal submucosal glands, which appear as small white structures detected during endoscopic submucosal dissection. In addition, we found the tumors with deeper invasion depth or larger circumferential extension tend to have more DIs. Whether these neoplastic cells have higher invasion or motility ability may require further in vitro studies.

DI may guide the choice of endoscopic therapy for early ESCN, especially when choosing tissue-destructive treatment. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or Cryoballoon ablation are both rapidly evolving treatment modalities, and some studies have shown good efficacy in treating the HGIN7,8,9,10. However, we recently reported the long-term outcome and found a high recurrence rate (20%) after RFA therapy11. While recurrent ESCNs usually presented as small and round lesions, 86% of them had DIs extension into the muscularis mucosae or submucosal layer11. In the current study, 15.5% of the involved ducts extended to the muscularis mucosae or submucosal layer in the lesions with HGIN. Because the maximal tumor ablation depth of RFA is the muscularis mucosae layer14, these deeply extended ducts will not be eradicated, which may potentially cause tumor recurrence or even buried cancer. Thus, the possibility of DI should be taken into account and may be a major limitation of ablation therapy.

Currently, endoscopic modalities such as conventional endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound or even image-enhanced endoscopy cannot detect DI. In this study, upper esophageal neoplasias, larger tumor circumferential extension, invasive histology and numerous small Lugol-unstained patterns in esophageal background mucosa were associated with the risk of esophageal DI. This finding may guide clinical decision making with regards to endoscopic treatment and surveillance. In histological examinations, we found that many of the involved ducts were located at the center of the lesions (77%), and nearly half of the involved ducts (52%) showed dilatation of the esophageal glandular duct. These signs suggest that some endoscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography or volumetric laser endomicroscopy17 may be able to detect and evaluate DI before treatment in the future.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was conducted at a single institute. Nevertheless, we demonstrated the significant impact of DI in endoscopic treatment and highlighted the importance of histological assessments of resected specimens. Second, we reviewed the post-ESD specimens retrospectively in our cohort, thus some of the esophageal glands were potentially not completely removed. A further prospective study is required to determine whether deeper submucosal dissection with total removal of esophageal submucosal glands can reduce tumor recurrence.

Data availability

We declare that all the data is available.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer. 127, 2893–917 (2010).

Chen, M. F. et al. Outcome of patients with esophageal cancer: a nationwide analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 20, 3023–30 (2013).

Lee, C. T. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal neoplasia: a single center experience in South Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 111, 132–9 (2012).

Oyama, T. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 3, S67–70 (2005).

Ono, S. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 70, 860–6 (2009).

Fujishiro, M. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 4, 688–94 (2006).

He, S. et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia: report of safety and effectiveness from a large prospective trial. Endoscopy. 47, 398–408 (2015).

Wang, W. L. et al. Radiofrequency Ablation Versus Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in Treating Large Early Esophageal Squamous Cell Neoplasia. Medicine. 94, e2240 (2015).

Wang, W. L. et al. A case series on the use of circumferential radiofrequency ablation for early esophageal squamous neoplasias in patients with esophageal varices. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 85, 322–9 (2017).

Canto, M. I. et al. Nitrous oxide cryotherapy for treatment of esophageal squamous cell neoplasia: initial multicenter international experience with a novel portable cryoballoon ablation system (with video). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 87, 574–81 (2018).

Wang, W. L. et al. Lessons from pathological analysis of recurrent early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia after complete endoscopic radiofrequency ablation. Endoscopy. 50, 743–750 (2018).

Nishimaki, T. et al. Tumor spread in superficial esophageal cancer: histopathologic basis for rational surgical treatment. World journal of surgery. 17:766–71; discussion 71-2 (1993).

Tajima, Y. et al. Significance of involvement by squamous cell carcinoma of the ducts of esophageal submucosal glands. Analysis of 201 surgically resected superficial squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer. 89, 248–54 (2000).

Dunkin, B. J. et al. Thin-layer ablation of human esophageal epithelium using a bipolar radiofrequency balloon device. Surgical endoscopy. 20, 125–30 (2006).

Lee, C. T. et al. Narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy for the screening of esophageal cancer in patients with primary head and neck cancers. Endoscopy. 42, 613–9 (2010).

Muto, M. et al. Association of multiple Lugol-voiding lesions with synchronous and metachronous esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in patients with head and neck cancer. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 56, 517–21 (2002).

Leggett, C. L. et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of volumetric laser endomicroscopy and confocal laser endomicroscopy in the detection of dysplasia associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 83, 880–88 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST-107-2314-B-650-006), E-Da Hospital (EDAHP106003), Taipei Medical University (TMU107-AE1-B19) and Taipei Medical University Hospital (107TMUH-NE-02). This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST-107-2314-B-650-006), E-Da Hospital (EDAHP106003), Taipei Medical University (TMU107-AE1-B19) and Taipei Medical University Hospital (107TMUH-NE-02). Dr. C-T Lee is accepting full responsibility for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. W.-L. Wang prepared the manuscript and analyzed the data. Drs. C.-T. Lee and H.-P. Wang initiated and coordinated the study. Dr. C.-T. Lee performed the procedure of ESD. Drs. W.-L. Wang, C.-T. Lee, T.-H. Chen, M.-H. Hsu, C.-M. Tseng, C.-H. Tseng, C.-M. Tai and H.-P. Wang enrolled the study subjects and followed up the endoscopies for all patients. Drs. I.-W. Chang and W.-L. Wang evaluated the histopathologic results. All authors have approved the final draft submitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, WL., Chang, IW., Hsu, MH. et al. Risk factors and pathological characteristics for intraductal tumor spread of submucosal gland in early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia. Sci Rep 10, 6860 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62668-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62668-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.