Abstract

The process of implantation, trophoblast invasion and placentation demand continuous adaptation and modifications between the trophoblast (embryonic) and the decidua (maternal). Within the decidua, the maternal immune system undergoes continued changes, as the pregnancy progress, in terms of the cell population, phenotype and production of immune factors, cytokines and chemokines. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is one of the earliest hormones produced by the blastocyst and has potent immune modulatory effects, especially in relation to T cells. We hypothesized that trophoblast-derived hCG modulates the immune population present at the maternal fetal interface by modifying the cytokine profile produced by the stromal/decidual cells. Using in vitro models from decidual samples we demonstrate that hCG inhibits CXCL10 expression by inducing H3K27me3 histone methylation, which binds to Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter, thereby suppressing its expression. hCG-induced histone methylation is mediated through EZH2, a functional member of the PRC2 complex. Regulation of CXCL10 expression has a major impact on the capacity of endometrial stromal cells to recruit CD8 cells. We demonstrate the existence of a cross talk between the placenta (hCG) and the decidua (CXCL10) in the control of immune cell recruitment. Alterations in this immune regulatory function, such as during infection, will have detrimental effects on the success of the pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coordinated balance between the invading trophoblast and a receptive maternal decidua is critical for the success of pregnancy1,2. The process of implantation, trophoblast invasion and placentation demand continuous adaptation and modifications between the trophoblast (embryonic) and the decidua (maternal)3,4,5. Within the decidua, the maternal immune system undergoes continued modifications, as the pregnancy progresses, in terms of the cell population, phenotype and production of immune factors, cytokines and chemokines6. These adaptation processes are essential for the normal progression of the pregnancy.

The decidua, the pregnant uterine endometrium, has long been considered as a supportive environment for the immune cells and the trophoblast present at the implantation site. However, growing evidence suggest that decidual stromal cells (DSCs) may play a more active role in the regulation of differentiation, migration and function of uterine immune cells7 as well as in the protection against infections8.

Immune cells are a major cellular component of the human and rodents’ pregnant uterus, and their specific role has been an area of active research. During the first trimester of the human pregnancy, 70% of the leukocytes found in the decidua are Natural Killer (NK) cells, 20% to 25% are macrophages, and approximately 1.7% are dendritic cells (DCs)9,10,11. In addition, the uterine T cell population expands across gestation, and are mostly regulatory in nature12. The recruitment of immune cells into the uterus is cell specific and their function is locally controlled7. Examples include the increase of NK cells at the end of the menstrual cycle, or recruitment of macrophages and DCs during the preimplantation period13. Human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) are known to produce and secrete various chemokines, including Interleukin-8 (IL-8)14,15, growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) α16,17,18, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)15,19, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1α)20, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES)21,22 and interferon-induced protein 10 (IP-10)23. The expression of these cytokines has been suggested to be important in menstruation, infections (bacterial and viral), implantation and in the support of early pregnancy24,25. Interestingly, the maintenance of pregnancy requires the inhibition of many of these cytokines/chemokines in order to restrict the recruitment of immune cells, such cytotoxic CD8 T cells that could endanger the acceptance of the fetus. Furthermore, several reports suggest that during pregnancy, the decidua is responsible for actively restricting access of cytotoxic CD8 T cells to the maternal-fetal interface26 suggesting that the process of differentiation from endometrial stromal cells into decidual cells involves the existence of active mechanisms regulating chemokine expression and function.

Human and animal studies have demonstrated that the cytokine milieu in the uterus is not only different between the pregnant and non-pregnant uterus, but it differs between early and late pregnancy6,27,28. Indeed, implantation and early trophoblast invasion have been shown to depend on the presence of inflammatory signals necessary for the attachment of the embryo to the surface epithelium of the uterus29. However, once implantation is achieved, the inflammatory environment needs to be reversed into an anti-inflammatory state in order to prevent maternal rejection of the embryo30,31. The signals regulating this shift at the implantation site have not yet been defined.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is one of the earliest hormones produced by the blastocyst and has potent immune modulatory effects, especially in relation to T cells32,33,34, B cells and dendritic cells35,36. hCG has been suggested to induce the immune modulatory changes in the phenotype and function of immune cells by either a direct pathway that involves the direct binding of hCG to its receptor on T and B cells34,37, or indirect pathways by inducing changes in regulatory cell populations such as dendritic cells38,39,40 or decidual/stromal cells. The interaction between hCG and stromal cell differentiation and immune regulatory function is unknown.

Several of the modifications taking place in the uterus in preparation for and during pregnancy are epigenetic modifications in response to local and systemic signals. The Polycomb-group (PcG) proteins make up the two Polycomb repressor complexes, PRC1 and PRC241 and are major regulators of cell differentiation. Each complex is composed of known core proteins, which represent the evolutionary conserved components of the complex42,43,44,45. Fine-tuning of the different components of each PRC has been observed in different cell types and in different cellular states46. In humans, PRC1 is composed of core proteins Bmi-1/Mel-18, CBX, RING1, and PHC while PRC2 is composed of EZH2, EED, and SUZ12. Multiple isoforms exist for each PcG protein and therefore, depending on the cell type and cellular state, the components of each PRC vary. PRCs suppress gene transcription through binding to the chromatin at the polycomb responsive elements (PRE) and promoting methylation47,48,49. EZH2 provides the methyltransferase activity on histone lysine residues that is essential for inducing transcriptional repression and stable gene silencing. Although it has been shown that the PcG proteins play an important role in the differentiation and function of decidual cells, the factors controlling these epigenetic modifications have not been elucidated. Previously, Nancy et al.50 reported in mice that CXCL9 and CXCL10, two important chemokines, are transcriptionally silenced during decidualization in the mouse uterus. This happened in association with promoter addition of tri-methyl histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a repressive histone mark generated by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2). H3K27me3 is an epigenetic modification to the DNA packaging protein Histone H3 and constitutes a mark that indicates the tri-methylation to the 27th lysine residue of the histone H3 protein. This tri-methylation is associated with the downregulation of nearby genes via the formation of heterochromatic regions51.

The objective of this study was to characterize the mechanisms associated with the regulation of the chemokine CXCL10 expression during the process of stromal-decidual differentiation. We tested the hypothesis that the trophoblast signal hCG, is responsible for the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, specifically CXCL10 expression by uterine stromal cells by regulating H3K27me3 histone modifications. We report the identification of a specific site at the promoter region of CXCL10 modified by H3K27me3 and show that hCG-induced H3K27me3 modification requires the recruitment of the PRC2 member EZH2. Furthermore, we describe the clinical correlation between circulating hCG and CXCL10 levels during early gestation in normal pregnancies.

Results

Decidual stromal cells (DSCs) secrete a specific cytokine profile that results in decreased CD8 T cell migration compared to stromal cells

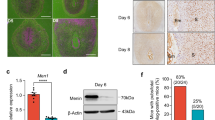

Our first objective was to determine the capacity of human endometrial stromal cells versus decidual cells to recruit immune cells and to characterize their chemokine profile. To achieve this objective, we used an in vitro model consisting of a telomerase immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line (HESCs) which can undergo in vitro differentiation into decidual cells (DSCs) by continued treatment with estrogen, progesterone and cAMP as previously reported and described in the Material and Methods52. In short, HESCs were exposed to estrogen, progesterone and cAMP for 5–9 days and the differentiation of HESCs into DSCs was confirmed by morphologic changes such as enlarged, rounded morphology compared to the elongated spindle-shaped fibroblastic stromal cells (Fig. 1A) and the increased expression of Prolactin and IGFBP-1 (Fig. 1B)52. Afterwards, we evaluated the capacity of these cells to recruit immune cells by using a 5 µM trans-well two-chamber migration assay where conditioned media (CM) collected from HESCs or DSCs (see M&M for preparation of CM) were added to the bottom chamber as chemoattractant and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (350,000 cells/well) were added to the upper chamber. After 24 h, all the cells that migrated into the lower chamber were collected and the number of T cells (CD4 and CD8) was evaluated by flow cytometry. We observed a significantly higher number of T cells present in the chambers containing HESCs’ CM (18,543 ± 115 T cells) compared to the chambers containing CM from DSCs (10,007 ± 1654 T cells) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). The proportion of recruited CD4 and CD8 T cells were significantly reduced in the chambers containing CM from DSCs compared to the chambers containing HESCs’ CM (Fig. 2A,C)

In vitro model of decidualization. A human endometrial stromal cell line (HESCs)52 was decidualized with 10 nM estradiol, 1 uM medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 500 uM 8-bromo cyclic AMP (cAMP) for 7 days. (A) Morphological changes associated with the decidualization process. The left panel shows the untreated HESCs, while the right panel shows the decidualized cells (DCS) after treatment with estradiol, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 8-bromo cyclic AMP. (B) Increased expression of Prolactin and IGFBP1 in decidualized cells (DSC) compared to HESC. Data presented as mean ± SD and are shown for 6 independent experiments with each done in triplicate. *p < 0.001.

Recruitment of immune cells by stromal cell- derived factors. Supernatants from HESC and decidualized HESC (DSC) cells were collected after 5 days of culture (equal confluence) and used as conditioned media (CM) for testing their effect on the migration of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using a two- chamber migration assay. PBMCs were added to the upper chamber for 24 h. The migrated cells (lower chamber) were collected, phenotyped, and counted by flow cytometry. (A) Representative figure of the different cell types collected in the lower chamber recruited by HESC and DSC’s conditioned media. Both CD4 and CD8 T cells migrated towards HESC CM and DSC CM. (B) Quantification of the total number of T cells recruited towards conditioned media obtained from HESC and DSC. Data shown are for 6 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate. *p < 0.001. (C) Flow Cytometry Analysis of CD4 and CD8 T cells. Percentage of CD4 and CD8 T cells recruited by DSC CM compared to HESC CM. DSC CM recruits significantly lower number of CD4 and CD8 T cells compared to HESC CM. Data presented as mean/SEM and are for 6 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

These findings suggest that HESCs are highly effective in recruiting T cells; however, differentiation into DSCs is associated with a significant drop in their recruitment capacity.

Cytokines and chemokines are the main mediators of immune cell recruitment; consequently, we evaluated, using Luminex analysis, whether there were differences in the cytokine and chemokine profile between HESC and DSCs that could explain the observed differential capacity to recruit T cells between these two cell types. Table 1 summarizes the cytokine/chemokine profile from supernatants obtained from these two cell types. HESCs are characterized by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL6, IL-12, IL-17, IFN-γ and chemokines IL-8, G-CSF CXCL-10, MIP-1α, VEGF and CCL5 (RANTES) (Table 1); however, upon differentiation into DSC cells, we observed a significant reduction in the secretion levels of these pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Table 1).

CXCL10 is a potent chemoattractant for CD8 + T cells and is highly expressed in the supernatant of HESCs but its expression is dampened upon differentiation into DSC; hence, we hypothesized that the decrease in migration of CD8 + T cells with the DSCs CM might be due to the inhibition of CXCL10 expression after decidualization. Accordingly, we sought to elucidate the potential mechanisms responsible for the regulation of CXCL10 expression in HESCs/DSCs and its impact on T cell recruitment.

hCG/cyclic AMP pathway regulates CXCL10 expression during cellular differentiation

In order to determine whether the process of differentiation from stromal cells into decidua cells is associated with the changes on CXCL10 expression, we evaluated CXCL10 mRNA levels in HESCs before and after differentiation into DSCs. Similar to the findings with the secreted protein, the process of decidualization is associated with transcriptional inhibition of CXCL10, demonstrated by decreased levels of CXCL10 mRNA in DSCs, which correlated with lower levels of secreted protein expression compared to the HESCs (Fig. 3A,B). Since estrogen and progesterone are known to be the main hormones involved in the process of decidual differentiation; we first tested the effect of either estrogen or progesterone on CXCL10 expression by stromal cells. Interestingly, neither estrogen nor progesterone were responsible for the modulatory effect on CXCL10 expression levels during decidualization (Fig. 3C). However, we did observe a significant inhibitory effect on CXCL10 mRNA and protein expression following cAMP treatment, the other major mediator of decidualization53 (Fig. 3A–C); suggesting that factors that could activate cAMP might have modulatory effects on CXCL10 expression.

Regulation of CXCL10 expression in stromal versus decidual cells. (A) Effect of cAMP and decidualization on CXCL10 mRNA expression. HESC were treated with 500 uM 8-bromo cAMP alone or decidualized with 10 nM estradiol, 1 uM medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 500 uM 8-bromo cyclic AMP for 7 days. Note the significant inhibition of CXCL10 mRNA expression by cAMP in HESC, similar to the decrease observed in the decidualized cells (DSC) *p < 0.05. Data presented as mean ± SD and are from 3 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate. (B) Quantification of CXCL10 protein expression in HESC treated with cAMP or decidualized with estrogen, progesterone and cAMP. cAMP treatment and decidualized cells (DSC) are associated with decreased CXCL10 protein expression. *p < 0.001. **p < 0.05. Data presented as mean ± SD and are from 3 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate. (C) Effect of estrogen, progesterone and cAMP on CXCL10 mRNA expression. HESC were treated with 10 nM estradiol, 1 uM medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), and 500 uM 8-bromo cAMP individually or under the combination of estradiol, MPA and cAMP for 7 days. CXCL10 mRNA was determined by qPCR. Note that only cAMP has a major effect on CXCL10 mRNA expression. Data presented as mean ± SD and are from 3 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate.

hCG is one of the early factors secreted by the trophoblast and is known to have immune modulatory effects during pregnancy, especially with regards to the recruitment of regulatory T and B cells33,34. The cellular effects of hCG are mediated through the LH receptor (LHR), a G-protein coupled receptor, and ligation of the receptor results in an increase in intracellular cAMP, its secondary messenger whose resulting protein cascades affect target gene expression54. Therefore, we hypothesize that hCG, though the induction of cAMP could inhibit recruitment of CD8+ T cells by suppressing CXCL10 expression in endometrial stromal cells. To test this hypothesis, we first evaluated the overall effect of hCG on cytokine/chemokine expression by HESCs. As shown in Table 1, column 3, hCG treatment had a notable inhibitory effect on HESCs’ cytokine and chemokine expression profile, similar to the one observed with the process of differentiation into decidual cells (Table 1).

Next, we characterized the potential transcriptional regulatory role of hCG on HESC’s CXCL10 expression by treating HESCs with hCG and determining CXCL10 mRNA expression. As shown in Fig. 4, HESCs treated with hCG revealed decreased CXCL10 mRNA expression (Fig. 4A) and this effect was dose and time dependent, further supporting the specificity of its effect (Fig. 4B,C). The inhibitory effect observed with hCG resembles the one determined with cAMP (Fig. 3).

Regulation of CXCL10 expression by hCG in human endometrial stromal cells (HESC). (A) HESC were treated with hCG 100 IU/ml for 24 h and CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. Note the significant decrease of CXCL10 mRNA expression after hCG treatment. Data presented as mean ± SD and are for 6 independent experiments with each group done in triplicate *p < 0.005. (B) Time response to hCG treatment (100 IU/ml). HESC were treated with hCG (100 IU/ml) for 2, 12 and 24 h and CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. CXCL10 mRNA expression decreased within 2 hours of hCG treatment and remained low up to 24 hours of treatment. (C) Dose response to hCG treatment. HESC were treated with increasing concentrations of hCG and CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. CXCL10 mRNA expression in HESC decreased in a dose dependent manner.

hCG/cyclic AMP pathway is an epigenetic regulator of CXCL10 expression by inducing histone methylation

Epigenetic modifications, such as histone methylation, play a central role in the regulation of cytokines and chemokines expression55; therefore, we hypothesized that the hCG/cAMP pathway may silence the promoter of CXCL10 (the human gene that codes for CXCL10) by histone methylation. As indicated above, H3K27me3 modification is associated with gene shutting down target gene transcription56,57. First, we determined whether the hCG/cAMP pathway could affect global H3K27 methylation by treating HESCs with hCG or cAMP for 2 h and evaluating H3K27me3 modification by western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 5A, HESCs cells treated with either hCG or cyclic AMP showed increased levels of H3K27me3 modification when compared to non-treated cells (Fig. 5A,B). Furthermore, when we expose HESCs to increasing concentrations of hCG, we observed a dose dependent increase on H3K27me3 modification (Fig. 5C,D). Total H3 was not affected by any of these treatments, confirming that the effect is associated with increasing methylation of H3K27 (Fig. 5A–D).

Regulation of H3K27me3 expression by hCG and cAMP in human endometrial stromal cells. (A) hCG and cAMP induce H3K27me3 in HESC. HESC were treated with hCG (100 IU/mL) or cAMP (500 uM) and H3K27me3 expression was determined by Western blot analysis. Representative western blot analysis showing hCG and cAMP enhanced H3K27me3 expression in HESCs. (B) Quantification of the western blot analysis showed in figure A. Data is presented as Relative Intense Units (RIU) as an average of 3 independent experiments. *p < 0.001. (C) Dose response effect of hCG on H3K27me3 expression. HESC were treated with increasing concentrations of hCG for 24 h followed by the determination of H3K27me3 expression by Western blot. hCG induces a dose dependent increase on H3K27me3 expression. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments done in triplicate. (D) Quantification of the western blot analysis showed in figure C. Data is presented as Relative Intense Units (RIU) as an average of 3 independent experiments.

Next, we sought to determine the molecular mechanism of how hCG mediates H3K27me3 modification. The PRC2 complex is the main regulator of H3K27me3 modification through the specific histone methyltransferase, EZH2. EZH2 catalyzes the methylation of Histone 3 at Lysine 27 (K27)45. Hence, we evaluated EZH2 in the regulation of H3K27me3 in HESC by using an inhibitor for EZH2, GSK126. Thus, DSCs, which express high levels of H3K27me3 and low levels of CXCL10, were treated with GSK126 (2μM) for 24 h followed by evaluation of CXCL10 mRNA expression and H3K27me3 by western blot analysis. Treatment of DSCs with GSK126 decreased H3K27me3 modification, as determined by western blot analysis (Fig. 6A); and, interestingly, correlated to enhanced CXCL10 mRNA expression (5-fold) (Fig. 6B). We then determined whether hCG effect on H3K27me3 could be mediated through the regulation of EZH2 expression. Thus, HESCs were treated with hCG and EZH2 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. We observed that hCG treatment had a modest, but significant effect on EZH2 mRNA expression (1.5-fold increase) (Fig. 6C). These findings further suggest an epigenetic regulation of CXCL10 expression in endometrial stromal cells.

Regulation of EZH2 expression by hCG in human endometrial stromal cells. (A) Treatment of HESC with the EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 (2μM) decreases H3K27me3 expression. HESC were treated with GSK126 (2μM) for 24 h followed by the evaluation of H3K27me3 expression by Western blot analysis. Note the decrease of H3K27me3 expression in the presence of GSK126. Representative Western blot analysis from 6 independent experiments. (B) Treatment of HESC with the EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 (2μM) increases CXCL10 mRNA expression. HESC were treated with GSK126 (2μM) for 24 h followed by the evaluation of CXCL10 mRNA expression by qPCR. Treatment with GSK126 is associated with significant increase in CXCL10 mRNA expression. *p < 0.002. Data shown as mean + SD and are for 6 independent experiments. (C) Effect of hCG on EZH2 mRNA expression. HESC were treated with hCG (100 IU/mL) for 24 h and CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. hCG treatment enhances EZH2 mRNA expression in HESC. *p < 0.05. Data shown as mean + SD and are for 3 independent experiments.

Specific Binding of H3K27me3 to the CXCL10 promoter in human decidual tissues

So far, we demonstrated in vitro, using cell lines, that hCG treatment affected H3K27me3 modification levels and correlates with CXCL10 mRNA and protein expression. Our next objective was to determine whether these findings are also present in freshly collected decidual tissue that has not undergone any in vitro manipulation. The main justification to use the whole decidual tissue is to avoid the potential non-specific effect of cell isolation and cell culture. Thus, decidual samples were obtained from term, non-labored, uncomplicated pregnancies undergoing scheduled cesarean delivery. Using these freshly collected decidual samples we then evaluated whether H3K27me3 modification is present in the tissues and if is responsible for the suppression of CXCL10 gene expression. First, we determined the enrichment of this histone mark on the CXCL10 promoter by performing chromatin immunoprecipitation using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody on freshly collected decidual tissue. After immune precipitation with the anti-H3K27me3 antibody we evaluated the enrichment of the histone mark in the CXCL10 promoter by using eight pairs of primers designed to span the 1000 bp upstream of the human CXCL10 gene. In human term uncomplicated non-labor decidua, we observed enrichment of H3K27me3 in Region 4 (505–601 base pairs upstream) of the human CXCL10 promoter (Fig. 7A,B). There was no appreciable enrichment in regions 1–3, or 5–8 (Fig. 7A,B). These findings were validated and quantified in six human decidua specimens (Fig. 7C,D). Only in region 4 we are able to obtain quantitative enrichment of H3K27me3 in the CXCL10 promoter (Fig. 7D). Figure 7C shows a representative DNA gel of the PCR product after chromatin immunoprecipitation demonstrating enrichment of the H3K27me3 to Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter in human decidua samples. The presence of the H3K27me3 mark at region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter correlates with low levels of CXCL10 mRNA expression in decidual tissue compared to stromal cells (Fig. 7E). Stroma cells are used as positive control for CXCL10 expression.

Identification of a novel site of epigenetic regulation in the CXCL10 promoter in term human decidual tissue. (A) Diagram of the CXCL10 promoter region. Eight specific primers were designed to cover the full length of the CXCL10 promoter region (IP-10 = CXCL10). (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed on human decidual samples collected from normal term non-labored placentas delivered by cesarean delivery. Decidual samples were crosslinked, sonicated and immunoprecipitated using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody. The DNA enriched with the H3K27me3 was purified and amplified by qPCR for the different regions of the CXCL10 promoter. Immunoprecipitation of H3K27me3 and PCR amplification of the DNA sequence bound by the histone demonstrated a strong band at Region 4 (505–601 base pairs upstream of the CXCL10 gene) in the promoter region of CXCL10 gene. No bands were detected at regions 1–3 or 5–8, indicating that the histone mark was not enriched in those regions. (C) PCR amplification of the DNA from Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter that was bound by the H3K27me3 after immunoprecipitation using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody. Representative figure of 6 independent decidual samples. (D) Quantification of the enrichment of the DNA sequence in the different regions of the CXCL10 promoter. Note that only Region 4 reveled binding to the H3K27me3 after ChIP qPCR. n = 6 human decidual tissue samples. (E) Relative CXCL10 mRNA expression levels from decidual tissue samples in relation to stromal cells. *p < 0.05. n = 6 human tissue samples.

hCG regulates the Binding of H3K27me3 to the CXCL10 promoter in human stromal cells

Having identified Region 4 as the site for H3K27me3 modification at the CXCL10 promoter in decidual tissues, our next objective was to determine whether hCG could promote this modification. Accordingly, we treated HESCs, expressing high levels of CXCL10, with hCG (100 IU/ml) for 2 h, followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation and PCR for enrichment of H3K27me3 mark at the CXCL10 promoter. Our data showed a 15-fold increased enrichment of H3K27me3 modification at Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter in HESCs treated with hCG compared to non-treated cells (Fig. 8A). Similar as reported with decidual tissues (Fig. 7), no modifications were found in the other regions; confirming the specificity for region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter.

hCG regulates CXCL10 expression and secretion by increasing H3K27me3 histone enrichment in Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. (A) HESC were treated with either vehicle or hCG (100 IU/ml). The cells were crosslinked, sonicated and immunoprecipitated using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody. The DNA enriched with the H3K27me3 was purified and amplified for Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. The results were quantified by ChIP qPCR. Note the significant enrichment of Region 4 bound to H3K27me3 in cells treated with hCG. *p < 0.05. Data shown are for 3 independent experiments. (B) Enrichment of the H3K27me3 mark in the CXCL10 promoter from HESC undergoing decidualization. HESC were decidualized with estrogen, progesterone and cAMP for 5 days. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed in HESC and decidualized stromal cells using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody. The enrichment was quantified using ChIP qPCR. Note the significant enrichment of Region 4 bound to H3K27me3 in decidualized cells compared to HESC. **p < 0.002. Data shown for 3 independent experiments.

We then compared whether similar effect is observed during the in vitro process of differentiation into decidual cells. Thus, HESC were exposed to estrogen, cAMP and progesterone for 5 days in order to induce decidualization, followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation and PCR for enrichment of the H3K27me3 mark at the CXCL10 promoter. As shown in Fig. 8B, we confirmed that the process of differentiation from HESCs to DSCs is associated with the enrichment of the histone mark to region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter (42-fold increase; p < 0.01) (Fig. 8B). No changes were observed in the other regions (Fig. 7B,D).

Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) inhibits H3K27me3 modification and induces CXCL10 expression in term human decidual tissue through the histone demethylase JMJD3

Our next objective was to determine the potential signals that could disrupt the regulation of CXCL10 expression by decidual cells. Since bacterial infections are a major cause of pregnancy complications and are able to induce and inflammatory process at the maternal/fetal interface including the expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines such as CXCL1058, we hypothesized that bacterial signals could induce CXCL10 expression by modifying the H3K27me3 mark and consequently promote the recruitment of maternal CD8+ T cells. To test this hypothesis, first we used the organ culture model of normal human term decidual tissue obtained from non-labored cesarean deliveries which, as described above, express low levels of CXCL10 and express high levels of the H3K27me3 mark at Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. Thus, decidual tissues were exposed to PBS (Control) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL) for 24 h and evaluated for the presence of H3K27me3 mark at region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter by chromatin immunoprecipitation using the anti-H3K27me3 antibody. In addition, we determined the expression of CXCL10 mRNA and protein by qPCR and Luminex assay, respectively. Decidual tissue samples exposed to control PBS showed strong enrichment of the H3K27me3 mark at Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter (Fig. 9A), which correlates with low levels of CXCL10 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 9C,D). That was not the case for the decidual samples treated with LPS where we observed a decrease of the H3K27me3 mark at Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter (Fig. 9A). Using ChIP qPCR we quantified the level of enrichment for H3K27me3 in Region 4 of CXCL10 promoter and confirmed the decrease of the H3K27me3 mark following LPS treatment compared to the control vehicle (Fig. 9B). Changes in the presence of H3K27me3 modification at the CXCL10 promoter correlated with the expression levels of CXCL10. Indeed, our data showed that LPS treatment, by decreasing the presence of H3K27me3 modification prompted increase on CXCL10 expression at the mRNA (Fig. 9C) and protein level (Fig. 9D). We observed a 10-fold increase in CXCL10 mRNA expression in the LPS treated group compared to the control vehicle (Fig. 9C). Similarly, at the protein level we observed a significant increase in the concentration of secreted CXCL10 in the LPS treated group (32,832.56 ± 1, 902.12 pg/mL) compared to control no treatment (13,886,86 ± 1,254.27 pg/mL*p < 0.05) (Fig. 9D). These findings further demonstrate that the H3K27me3 modification is present in human decidual tissue, regulating CXCL10 expression and can be modified by signals induced by bacterial products such as LPS.

Effect of LPS on CXCL10 expression and secretion. (A) Human term decidua tissues were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody. The DNA enriched with the H3K27me3 was purified and amplified by qPCR for Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. Note the decreased binding of the H3K27me3 to region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter observed in cells treated with LPS compared to the control (PBS) treated group. Representative figure of 6 independent experiments. (B) Quantification of the enrichment of the DNA sequence of region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter bound to H3K27me3. The enrichment was quantified using ChIP qPCR and reveled decreased enrichment in decidual samples exposed to LPS. p < 0.05. (C) Effect of LPS on CXCL10 mRNA expression. Human term decidua tissue samples were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24. CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. LPS treatment induces a significant increase on CXCL10 mRNA expression in human term decidua tissues n = 6, *p < 0.05. (D) Human term decidua tissues were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 followed by evaluation of CXCL10 protein expression by Luminex. LPS induces CXCL10 protein secretion in decidual samples. n = 6, *p < 0.001.

Next, we evaluated the mechanism how LPS decreases the H3K27me3 mark at Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. We screened for changes in the expression of known H3K27me3 histone demethylases such as KDM6A and JMJD359 in response to LPS treatment and found that the mRNA expression of JMJD3, a histone demethylase specific to the methylated histone H3K27me3, was affected by LPS treatment. Thus, when decidual organ cultures were exposed to PBS (Control) or LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h and evaluated JMJD3 mRNA expression, decidual organ cultures exposed to LPS showed a 3-fold increase in JMJD3 mRNA expression compared to the PBS control (p < 0.05) (Fig. 10A). The increase in JMJD3 expression correlated with LPS-induced decrease of H3K27me3 modification from the CXCL10 promoter (Fig. 9A,B) and increased CXCL10 mRNA expression and protein secretion (Fig. 9C,D).

Role of JMJD3 in the regulation of CXCL10 expression and secretion. (A) Expression of JMJD3 in human decidual tissue. Human term decidual tissues were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and JMJD3 expression was determined by qPCR. LPS treatment enhances JMJD3 mRNA expression. n = 6, *p < 0.05. (B) Inhibition of JMJD3 function with the inhibitor GSKJ4 prevents LPS-induced CXCL10 expression. Human term decidual tissues were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of GSKJ4, an inhibitor of JMJD3 for 24 h. CXCL10 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The presence of GSKJ4 inhibits LPS induced CXCL10 expression. *p < 0.05. (C) Quantification of the total number of T cells recruited towards conditioned media obtained from HESC and DSC in the presence or absence of LPS treatment (100 ng/ml). Transwell migration assays were performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells and conditioned media from HESC and DSC treated with LPS or vehicle (control). LPS treatment is associated with increased number of T cells collected in the lower chamber (recruitment chamber). n = 6 independent experiments. Each group was done in triplicates. *p < 0.001. (D) Flow Cytometry Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recruited by DSC CM in relation to HESC CM was determined by flow cytometry. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were identified in the Transwell migration assays. Representative flow cytometry from four independent experiments.

To further confirm the role of JMJD3, we treated the decidual organ cultures with GSK-J4, a specific JMJD3 inhibitor, in the presence or absence of LPS and then examined CXCL10 expression levels. As shown in Fig. 10B, pre-treatment of decidual organ cultures with the GSK-J4 reversed the effect of LPS on CXCL10 mRNA expression. While LPS treatment induced a 19-fold increased on CXCL10 mRNA expression, the presence of GSK-J4 significantly reduced LPS-induced CXCL10 mRNA expression (Fig. 10B; p < 0.05). GSK-J4 treatment alone did not affect CXCL10 mRNA expression (Fig. 10B). This data demonstrates that infection can induce a strong and quick inflammatory response by decreasing the H3K27me3 modification through the induction of the expression of the histone demethylase JMJD3.

LPS removal of H3K27me3 modification in DSCs results in increased recruitment of CD8 + T cells

Finally, we determined whether LPS, by decreasing the H3K27me3 modification and enhancing CXCL10 expression could affect the capacity of DSCs to recruit T cells. Thus, we used the same trans-well migration assay as described in Fig. 2. PBMC were added to the upper chamber and then exposed to CM in the lower chamber obtained from: (1) DSCs treated with vehicle (control) or (2) DSCs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. This concentration of LPS has no detrimental effect on DSCs60,61,62,63. As shown in Fig. 10C, LPS treatment of HESC and DSCs enhances the recruitment of T cells. Indeed, CM from DSCs treated with LPS attracted more T cells than CM from non-treated DSCs (11,832 ± 821.7 vs 1905 ± 165, p < 0.05). A high percentage of the recruited cells were CD8 + and CD4 + T cells (Fig. 10D).

Inverse correlation between hCG and CXCL10 levels in early pregnancy

So far as we have described in vitro, there is an inverse correlation between hCG and CXCL10 expression. Since CXCL10 expression levels has been shown to be higher during human embryo implantation64 and subsequently decreased throughout the pregnancy65, we explored whether we could detect and determine in the serum of pregnant women a potential correlation between circulating hCG and CXCL-10 in the first 8 weeks of pregnancy, a period when hCG production increases as result of successful placentation. Although circulating cytokines can be affected by multiple processes taking place in the body, it is the only non-invasive source for evaluating some of the changes occurring during pregnancy66. To achieve this objective, we recruited an IVF cohort where we were able to monitor the day of implantation and collect samples from the earliest stages of pregnancy (between 3 and 6 weeks of gestation) and measured hCG and CXCL10 in the serum of these pregnant women throughout the first trimester of pregnancy. We detected CXCL10 in the serum of pregnant women as early as 9 days after embryo transfer and it serum levels remained constant during the subsequent days (SFig. 3). Circulating hCG levels gradually increased as pregnancy progresses (Fig. 11A); interestingly, when we look at the ratio between CXCL10 and hCG we observed an inverse correlation as the pregnancy progressed (Fig. 11B). This is a noteworthy association since CXCL10 is known to be high during implantation and then silenced to prevent the recruitment of T cells64.

hCG and CXCL10 expression ratio throughout early gestation. Circulating levels of hCG and CXCL10 were measured using ELLA assay in serum samples collected from normal pregnant women during the first 4 weeks of pregnancy. (A) hCG is detected in the serum as early as 9 days after embryo transfer and shows a steady increase in the following days. (B) Ratios of CXCL10 and hCG across gestational age were determined in blood samples collected from IVF pregnancies. The line represents the mean estimation by LOWESS and the colored areas the 95% confidence intervals of the mean estimation. CXCL10:hCG ratios decreased in normal pregnancies in relation to gestational age.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the epigenetic role of hCG in the regulation of CXCL10 in the human decidua. We report for the first time, the identification of a specific site for the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 in the promoter of the human CXCL10gene (Region 4, 505–601 kb upstream). Furthermore, we describe the role of hCG as a regulator of CXCL10 expression by controlling the H3K27me3 mark through the expression of the histone methyltransferase, EZH2. We show that this mark can then be modified by bacterial products leading to an increase in CXCL10 expression and enhancement of the recruitment of pro-inflammatory CD8 + T cells. The modification of H3K27me3 mark is mediated by JMJD3, a histone demethylase. Our studies show an active epigenetic crosstalk between the trophoblast and decidua that results in chemokine suppression. These findings are relevant because they describe a novel mechanism of fetal-maternal anti-inflammatory regulation that can be disrupted during infection, potentially leading to inflammation and preterm birth.

One important issue to recognize is that not all inflammation in pregnancy is detrimental. The correct timing of inflammation is essential to a healthy pregnancy. For example, it is well established that implantation in the first trimester is a pro-inflammatory event67,68,69,70,71 as is labor at the end of the third trimester72,73,74,75. On the other hand, the second trimester of pregnancy is characterized by an anti-inflammatory profile31,76. In pathological states, shifts towards a pro- inflammatory profile before term are associated with preterm birth77,78,79,80,81,82,83. Therefore, tight regulatory control of inflammation between the fetus/trophoblast unit and the decidua is critical in preventing preterm birth.

CXCL10 (IP-10) is a 77 amino acid, 10kDA protein that belongs to the CXC family of chemokines84, and has been shown to have pleiotropic biological activities23. CXCL10 is the most potent chemoattractant for cytotoxic CD8 + T cells85 and elevated levels of CXCL10 in maternal serum, amniotic fluid, and neonatal cord blood have been associated with infection and preterm birth21,86,87,88. In the mouse, it was described ex vivo that the promoter region of the chemokines CXCL9 and CXCLl10 revealed elevated levels of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 in DSCs versus myometrial cells, which was then confirmed in vivo26. Methylation of histone 3 at Lysine 27 (K27) is one of the most well-described epigenetic modifications. When H3K27 is trimethylated to H3K27me3, it is tightly associated with its target gene promoter, inactivating the promoter, and consequently shutting down target gene transcription50,56,57. These findings suggest that epigenetic modifications of stromal/decidual cells are critical regulators of these chemokines and consequently of the immune regulation at the maternal fetal interface.

CXCL10 is a potent pro-inflammatory chemokine whose regulation appears to be important during pregnancy. Human cohort studies have shown that not only does CXCL10 expression increase with normal term labor (as do other inflammatory cytokines), but importantly, elevated levels of CXCL10 are associated with preterm birth and chorioamnionitis, suggesting that CXCL10 suppression in the decidua is necessary for the normal course of pregnancy21,87,89. Recently, the notion of a decidual clock has been proposed, wherein “timing of labor” is dependent on the suppression and release of certain elements at the correct timepoint during pregnancy. In the beginning of pregnancy, suppressive factors function to maintain the pregnancy and prevent miscarriage. The suppression is then released at the end of pregnancy and allows labor to occur90. Our data support this theory of the decidual clock by describing the regulation of CXCL10 in the decidua. By secreting hCG in the beginning of the pregnancy, the fetal/placental unit works to “set the timing” on the decidual clock, to suppress inflammatory mediators such as CXCL-10. Based on our data, we propose that hCG is the fetal anti- inflammatory factor of pregnancy (Fig. 12).

Regulation of CXCL10 by hCG and its relevance during pregnancy. (A) hCG, through cAMP enhances the expression of EZH2 increasing H3K27me3 histone methylation which binds to region 4 of CXCL10 promoter region and consequently inhibiting CXCL10 expression. (B) Trophoblast derived hCG inhibits CXL10 expression by decidual cells preventing T cell recruitment.

Our data support hCG’s anti-inflammatory and tolerance- promoting functions. Human chorionic gonadotropin, a factor secreted by the trophoblast, has already known immunological properties: It promotes the induction and activation of regulatory T cells, and these cells are necessary for the successful establishment of pregnancy33,34. hCG treatment of dendritic cells prior to conception induces regulatory T cell expansion and leads to decreased spontaneous abortion in mice35. In addition, hCG stimulates macrophage function and activation91,92. In our study, hCG and its downstream messenger cyclic AMP- treatments both suppress CXCL10 expression and secretion in stromal cells. CXCL10 suppression supports the anti-inflammatory function of hCG. CXCL10 suppression also results in decreased CD8 + T cell migration in decidual cells compared to stromal cells. This data is in line with others who have found that hCG down-regulates CD8 + T cells in pregnancy93. Furthermore, hCG suppresses not only CXCL-10, but other pro-inflammatory cytokines as well, such as GRO-alpha, IL-8, IL-17, and RANTES. Kokdehoff and others also found that hCG decreases inflammatory cytokines in women treated with hCG prior to IVF94. However, our data go beyond mere description, and we characterize the mechanism by which the fetal factor hCG suppresses CXCL10 expression in decidual cells as it may promote maternal tolerance.

We describe how the fetus/placental unit is an active participant in the process of fetal-maternal tolerance: It acts through hCG using epigenetic mechanisms to suppress inflammation. Our data illustrate a novel role of hCG as a functional epigenetic regulator suppressing inflammation. Treatment of stromal cells with hCG upregulates EZH2, a specific histone methyltransferase, enriching the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 in Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. This enrichment results in decreased expression and secretion of CXCL-10. In addition, enrichment of the H3K27me3 (and subsequent suppression of CXCL-10) also occurred during decidualization with cyclic AMP. This data supports a role of hCG in maintaining the normal state of pregnancy.

We also show how infection can induce inflammation and break the fetal-maternal tolerance by disrupting the epigenetic mechanism. In our organ culture experiments using term uncomplicated human samples, we are able to induce CXCL10 expression and secretion with LPS treatment. Moreover, we show that LPS treatment decreases the enrichment of H3K27me3 in Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter. LPS affects H3K27me3 methylation by inducing JMJD3, a histone demethylase, which is also seen in the regulation of other pro-inflammatory cytokines in HUVEC cells95.

In conclusion, our data demonstrates how the fetus/trophoblast unit actively participates in regulating inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface in order to promote pregnancy. The epigenetic inhibition of CXCL10- mediated inflammation is promoted by hCG on stromal cells. However, in cases of infection, LPS can modulate the suppression, and induce inflammatory chemokines that will recruit cytotoxic T cells to the maternal-fetal interface. Our results provide a possible mechanism by which infection can induce pregnancy complications such as preterm birth (Fig. 12).

As an anti-inflammatory agent, hCG may have therapeutic potential for prevention of miscarriage and preterm birth in pregnancies complicated by infection. Further clinical trials are needed to investigate the therapeutic role of hCG for prevention of fetal loss.

Materials and Methods

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by Yale University

Reagents and cell line

Reagents and cell line used in the experiments were as follows: LPS isolated from E. coli 0111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), GSK-J4 and GSK126 were purchased from (ApexBio, Houston, TX) and telomerase-immortalized human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) were developed in our laboratory and previously reported52,96.

In-vitro decidualization of a uterine stromal cell line

HESC cell line was decidualized as previously described52,96. In short, HESC was cultured in DMEM low-glucose medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Waltham, MA). Upon reaching confluency, the HESCs were switched to Optimem (Gibco, Waltham, MA) and treated for 7 days with 10 nM β2-estradiol, 1 μM medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 500 μM 8-bromo cyclic AMP. On day 8, the cells were trypsinized and the cell pellets were collected for RNA extraction.

Endometrial stromal cells conditioned media preparation

Human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) were plated at 5 × 105 cells/100 mm dish with 10% FBS DMEM-F12 media and allowed to attach overnight. Upon reaching confluency, the uterine stromal cells were switched to Optimem (Gibco, Waltham, MA) and differentiated into decidual cells by treating them for 5 days with 10 nM β2-estradiol, 1 μM medroxyprogesterone acetate, and 500 μM 8-bromo cyclic AMPM. Control cells received vehicle for the same length of time. After 5 days media was then changed to 1 Optimem media and incubated for additional 48 hrs. Cell supernatant was collected and spun down to remove any cellular debris. Cell free supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and ChIP-PCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed on the treated uterine stromal cell line and the decidua tissue using the Zymo-Spin ChIP Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Irvine, CA). Briefly, the tissue was mechanically homogenized, crosslinked, and then immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and a rabbit anti-IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). The ChIP DNA was purified and stored until they were ready for PCR.

The previously stored DNA purified after chromatin immunoprecipitation was used for PCR. Eight pairs of primers were designed to span the 1000 bp upstream of the human CXCL10gene in order to identify the binding site(s). The PCR product was then run on a 1% DNA Agarose gel and imaged using the Kodak Image Station 4000 (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT). When the location of enrichment was identified (Region 4), that primer set was used for the subsequent ChIP PCR reactions. The purified ChIP DNA was used for real-time PCR using the primers from Region 4 to quantify the enrichment of the H3K27me3 histone to Region 4 of the CXCL10 promoter.

Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from the samples using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Waltham, MA). cDNA was prepared using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as previously described97.

Luminex multiplex assay

After culture and treatment, the supernatant was collected, centrifuged, aliquoted, and stored until use. The samples were thawed only once immediately prior to running the assay. The samples were run on the Luminex Multiplex Assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for the following cytokines and chemokines: GROa, IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-Y, CXCL-10, MCP-1, MIP-1a, MIP-1b, RANTES, TNF-a, and VEGF.

Cell migration experiments

Transwell migration experiments were performed using conditioned media from the non-decidualized and decidualized uterine stromal cell line. PBMCs were seeded in 5µm-inserts (3 × 105 cells/insert) (BD Falcon cell culture inserts), which then were set in a 24-well plate containing the conditioned media from the stromal cells under different treatments. After 24 hours, the cells were recovered from the lower compartment and the total number of migrating cells was quantified. In addition, the percentage of CD4 or CD8 cells were quantified by FACS analysis. The results are expressed relative to basal conditioned for each assay.

Flow-cytometry analysis

T lymphocytes were stained with the following mAbs: mouse anti-human CD4 PE conjugated, mouse and anti-human CD8 APC conjugated, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Briefly, after recovery, the cells were washed and surface stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8. The levels of CD4 and CD8 T cells were then quantified.

Western blot

Western blot was performed using a monoclonal anti- H3K27me3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The cells were lysed and sonicated with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein were boiled in SDS-containing sample buffer, resolved on SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with the anti-H3K27me3 antibody.

Organ culture experiments

The Institutional Review Board of Yale University approved the collection and use of these tissues for research purposes (HIC# 12696). Organ culture experiments were performed using decidual tissue isolated from the placentae of term uncomplicated non-labored pregnancies at the time of scheduled cesarean delivery. Immediately upon delivery, the decidua was separated from the fetal membranes, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline, and cut into approximately 3 × 3 mm pieces and placed in DMEM media supplemented with Normocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for 24 hours. The following day, the media was refreshed, the tissue was treated with either LPS or inhibitors, and after 24 hours, it was collected for RNA isolation or crosslinked for chromatin immunoprecipitation. Supp Fig. 1 shows a representative H&E stained slide of the decidua tissue used for the organ culture experiments.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed on the treated uterine stromal cell line and the decidua tissue using the Zymo-Spin ChIP Kit (Irvine, CA). Briefly, the tissue was mechanically homogenized using an Omni TH tissue homogenizer (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA) then all samples were crosslinked using 1% formaldehyde. The crosslinking reaction was stopped using 0.125 M glycine. The samples were then washed with phosphate buffered saline supplemented with protease inhibitors, centrifuged, and stored at −80 °C until ready for use. Next, the samples were sonicated to a size of approximately 250 bp size using a Sonic Dismembrator 500 (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The size of the chromatin was confirmed by running the sheared chromatin on a DNA 1% Agarose gel. After sonication, the immunoprecipitation reaction was performed using an anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and a rabbit anti-IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) as a negative control and the ZymoMag Protein A beads supplied with the kit. The samples were washed with the provided wash buffers, then reverse crosslinked, and the resulting DNA was purified and stored until they were ready for PCR.

ChIP-qPCR

ChIP Primers used in this study: The 8 primer sequences corresponding to the location in the CXCL10 promoter are as follows:

Region 1: F: CCATTTTCCCTCCCTAATTC, R: CCTTCGAGTCTGCAACATG

Region 2: F: GTAGCCTCCAAGTTACGG, R: GAATGGATTGCAACCTTTG

Region 3: F: CAAAGGTTGCAATCCATTC, R: CACAACTTGCTGTTACC

Region 4: F: GAACAGTGATTTACCTGGACA, R: CTTGCCAGTTCCAGATCTTTG

Region 5: F: GACAGGGTCAAAGATCTGG, R: CCCTCAAAATAGTTATGTTGG

Region 6: F: CATTGCTCATTTGGGTATCTGA, R: CAATAACCCTAGGATAGCTATG

Region 7: F: AGGGTGCTTTTTGAGGA, R: ACAGTGTCTTGGAGCTGA

Region 8: F: CTCCAAGACACTGTTAAATG, R: GCCACGATTCATCATCC

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using the following primers:

CXCL-10: F: CCCACGTGTTGAGATCATTG, R: TCCATCACAGCACCGGG,

JMJD3: F: AGTACCGCACTGAGGAGCTG, R: CAGTGCCCTCCTCCGCT,

EZH2: F: TGCACATCCTGACTTCTGTGA, R: TCATCTCCCATATAAGGAATGTTATG,

Prolactin: F: CATCAACAGCTGCCACACTT, R: CGTTTGGTTTGCTCCTCAAT,

IGFBP1: F: CTATGATGGCTCGAAGGCTC, R: TTCTTGTTGCAGTTTGGCAG,

GAPDH: F: TTAAAAGCAGCCCTGGTGAC, R: CTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTCGAC.

Patient recruitment and sample collection

The description of the patients population, recruitment and characteristics has been previously described98 as following:

IVF Cohort

Recruitment of IVF patients and storage of samples was approved by the Yale institutional Review Board (IRB) with no written consent requirement (#2000021607). All the participants had an informed consent for study participation. An aliquot of blood was assigned for the study during the regular blood test for monitoring chemical pregnancy (hCG serum levels). The study was deemed to have minimal harm to patients so only verbal consent was requested. The investigators have no access to any personal information. Coded serum samples were provided to the investigators without any patient information.

Patients aged 18–44 undergoing fresh or frozen day 3 or day 5 (blastocyst) embryo transfer from October 2017 to July 2018 were eligible for participation. Exclusion criteria were patients with chronic autoimmune disease (such as lupus, thyroid antibodies, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease), diabetes and hypertension requiring medication, endometriosis confirmed by laparoscopy, or current illness (in general, we excluded patients with an underlying inflammatory process). We also excluded patients with prior pregnancy losses, unless the tissue from the loss had undergone genetic testing and was determined to be chromosomally abnormal. Patients were asked to participate at the time of embryo transfer. Blood was collected by venipuncture into 10 mL vacutainer tubes starting at the time of the first positive β-hCG, 8–12 days after embryo transfer and then every 48 hours until an intrauterine pregnancy was confirmed using transvaginal ultrasound, or when a pregnancy was deemed as biochemical based on declining β-hCG levels following an initial positive test. Samples were left at room temperature for 60 minutes to allow for clotting and then centrifuged (Thermo Scientific Sorvall ST 16, Waltham, MA) at 3,000 RPM for ten minutes at room temperature. Serum was aliquoted into 1.5 mL polypropylene RNase- and DNase-free microcentrifuge tubes and stored in −80 °C freezers until ready for testing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses was done using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for windows and GraphPad Prism software, version 5. Differences between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The differences between multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Chi-square test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All the experiments were done in triplicate and a minimum of three independent experiments.

References

Urban, G. et al. New placental factors: Between implantation and inflammatory reaction. Early pregnancy: Biol. medicine: Off. J. Soc. Investigation Early Pregnancy 5, 70–71 (2001).

van Mourik, M. S., Macklon, N. S. & Heijnen, C. J. Embryonic implantation: cytokines, adhesion molecules, and immune cells in establishing an implantation environment. J. Leukoc. Biol. 85, 4–19 (2009).

Norwitz, E., Schust, D. & Fisher, S. Implantation and the survival of early pregnancy. NEJM 345, 1400–1408 (2001).

Nardo, L. G., Li, T. C. & Edwards, R. G. Introduction: human embryo implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage: basic science and clinical practice. Reprod. Biomed. Online 13, 11–12 (2006).

Paria, B. C., Lim, H., Das, S. K., Reese, J. & Dey, S. K. Molecular signaling in uterine receptivity for implantation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 67–76 (2000).

Mor, G., Cardenas, I., Abrahams, V. & Guller, S. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1221, 80–87 (2011).

Erlebacher, A. Immunology of the maternal-fetal interface. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 387–411 (2013).

Anders, A. P., Gaddy, J. A., Doster, R. S. & Aronoff, D. M. Current concepts in maternal-fetal immunology: Recognition and response to microbial pathogens by decidual stromal cells. Am J Reprod Immunol 77 (2017).

Bulmer, J. N., Pace, D. & Ritson, A. Immunoregulatory cells in human decidua: morphology, immunohistochemistry and function. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 28, 1599–1613 (1988).

Aldo, P. B., Mulla, M. J., Romero, R., Mor, G. & Abrahams, V. M. Viral ssRNA Induces First Trimester Trophoblast Apoptosis through an Inflammatory Mechanism. Am J Reprod Immunol (2010).

Gardner, L. & Moffett, A. Dendritic cells in the human decidua. Biol. Reprod. 69, 1438–1446 (2003).

Tilburgs, T., Claas, F. H. & Scherjon, S. A. Elsevier Trophoblast Research Award Lecture: Unique properties of decidual T cells and their role in immune regulation during human pregnancy. Placenta 31(Suppl), S82–86 (2010).

Birnberg, T. et al. Dendritic cells are crucial for decidual development during embryo implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 57, 342 (2007).

Luk, J. et al. Regulation of interleukin-8 expression in human endometrial endothelial cells: a potential mechanism for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 1805–1811 (2005).

Mulayim, N., Palter, S. F., Kayisli, U. A., Senturk, L. & Arici, A. Chemokine receptor expression in human endometrium. Biol. Reprod. 68, 1491–1495 (2003).

Fukuda, J. et al. Effects of leptin on the production of cytokines by cultured human endometrial stromal and epithelial cells. Fertil. Steril. 80(Suppl 2), 783–787 (2003).

Nasu, K., Fukuda, J., Sun, B., Nishida, M. & Miyakawa, I. Interleukin-13 and tumor necrosis factor-beta differentially regulate the production of cytokines by cultured human endometrial stromal cells. Fertil. Steril. 79(Suppl 1), 821–827 (2003).

Nasu, K., Matsui, N., Narahara, H., Tanaka, Y. & Miyakawa, I. Effects of interferon-gamma on cytokine production by endometrial stromal cells. Hum. Reprod. 13, 2598–2601 (1998).

Senturk, L. M. et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in human corpus luteum. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 5, 697–702 (1999).

Nasu, K. et al. Platelet-activating factor stimulates cytokine production by human endometrial stromal cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 5, 548–553 (1999).

Aminzadeh, F. et al. Differential expression of CXC chemokines CXCL10 and CXCL12 in term and pre-term neonates and their mothers. Am. J. Reprod. immunology 68, 338–344 (2012).

Arima, K. et al. Effects of lipopolysaccharide and cytokines on production of RANTES by cultured human endometrial stromal cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 6, 246–251 (2000).

Kai, K. et al. Expression of interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8, 176–180 (2002).

Garcia-Velasco, J. A., Arici, A., Zreik, T., Naftolin, F. & Mor, G. Macrophage derived growth factors modulate Fas ligand expression in cultured endometrial stromal cells: a role in endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 5, 642–650 (1999).

Garcia-Velasco, J. A. & Arici, A. Chemokines and human reproduction. Fertil. Steril. 71, 983–993 (1999).

Nancy, P. et al. Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal-fetal interface. Science 336, 1317–1321 (2012).

Neale, D., Visintin, I., Abrahams, V. & Mor, G. Challenging the TH1/TH2 paradigm of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 195, S155 (2006).

Ng, S. C. et al. Expression of intracellular Th1 and Th2 cytokines in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion, implantation failures after IVF/ET or normal pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 48, 77–86 (2002).

Plaks, V. et al. Uterine DCs are crucial for decidua formation during embryo implantation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3954–3965 (2008).

Mor, G. & Cardenas, I. The immune system in pregnancy: A unique complexity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 425–433 (2010).

Mor, G., Aldo, P. & Alvero, A. B. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol (2017).

Sauss, K., Ehrentraut, S., Zenclussen, A. C. & Schumacher, A. The pregnancy hormone human chorionic gonadotropin differentially regulates plasmacytoid and myeloid blood dendritic cell subsets. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 79, e12837 (2018).

Schumacher, A. et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin attracts regulatory T cells into the fetal-maternal interface during early human pregnancy. J. Immunol. 182, 5488–5497 (2009).

Schumacher, A. et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin as a central regulator of pregnancy immune tolerance. J. Immunol. 190, 2650–2658 (2013).

Dauven, D., Ehrentraut, S., Langwisch, S., Zenclussen, A. C. & Schumacher, A. Immune Modulatory Effects of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin on Dendritic Cells Supporting Fetal Survival in Murine Pregnancy. Front. Endocrinol. 7, 146 (2016).

Fettke, F. et al. Maternal and Fetal Mechanisms of B Cell Regulation during Pregnancy: Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Stimulates B Cells to Produce IL-10 While Alpha-Fetoprotein Drives Them into Apoptosis. Front. immunology 7, 495 (2016).

Schumacher, A., Poloski, E., Sporke, D. & Zenclussen, A. C. Luteinizing hormone contributes to fetal tolerance by regulating adaptive immune responses. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 71, 434–440 (2014).

Bourdiec, A., Calvo, E., Rao, C. V. & Akoum, A. Transcriptome analysis reveals new insights into the modulation of endometrial stromal cell receptive phenotype by embryo-derived signals interleukin-1 and human chorionic gonadotropin: possible involvement in early embryo implantation. PLoS One 8, e64829 (2013).

Carbone, F. et al. Divergent immunomodulatory effects of recombinant and urinary-derived FSH, LH, and hCG on human CD4+ T cells. J. Reprod. Immunol. 85, 172–179 (2010).

Schafer, A., Pauli, G., Friedmann, W. & Dudenhausen, J. W. Human choriogonadotropin (hCG) and placental lactogen (hPL) inhibit interleukin-2 (IL-2) and increase interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta), -6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) expression in monocyte cell cultures. J. Perinat. Med. 20, 233–240 (1992).

Bantignies, F. et al. Polycomb-dependent regulatory contacts between distant Hox loci in Drosophila. Cell 144, 214–226 (2011).

Leeb, M. et al. Polycomb complexes act redundantly to repress genomic repeats and genes. Genes. Dev. 24, 265–276 (2010).

Leeb, M. & Wutz, A. Polycomb complexes - Genes make sense of host defense. Cell Cycle 9, 2692–2693 (2010).

Lin, Z. P., Belcourt, M. F., Cory, J. G. & Sartorelli, A. C. Stable suppression of the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase by R2-targeted short interference RNA sensitizes p53(−/−) HCT-116 colon cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents and ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27030–27038 (2004).

Margueron, R. & Reinberg, D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469, 343–349 (2011).

Richly, H., Aloia, L. & Di Croce, L. Roles of the Polycomb group proteins in stem cells and cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2, e204 (2011).

Morey, L. & Helin, K. Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends biochemical Sci. 35, 323–332 (2010).

Schuettengruber, B., Chourrout, D., Vervoort, M., Leblanc, B. & Cavalli, G. Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell 128, 735–745 (2007).

Tolhuis, B. et al. Genome-wide profiling of PRC1 and PRC2 Polycomb chromatin binding in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 38, 694–699 (2006).

Nancy, P. et al. H3K27me3 dynamics dictate evolving uterine states in pregnancy and parturition. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 233–247 (2018).

Ferrari, K. J. et al. Polycomb-dependent H3K27me1 and H3K27me2 regulate active transcription and enhancer fidelity. Mol. Cell 53, 49–62 (2014).

Krikun, G. et al. A novel immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line with normal progestational response. Endocrinology 145, 2291–2296 (2004).

Dunn, C. L., Kelly, R. W. & Critchley, H. O. Decidualization of the human endometrial stromal cell: an enigmatic transformation. Reprod. Biomed. Online 7, 151–161 (2003).

Ryu, K. S., Gilchrist, R. L., Koo, Y. B., Ji, I. & Ji, T. H. Gene, interaction, signal generation, signal divergence and signal transduction of the LH/CG receptor. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 60(Suppl 1), S9–20 (1998).

Yano, S., Ghosh, P., Kusaba, H., Buchholz, M. & Longo, D. L. Effect of promoter methylation on the regulation of IFN-gamma gene during in vitro differentiation of human peripheral blood T cells into a Th2 population. J. Immunol. 171, 2510–2516 (2003).

Muller, J. et al. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111, 197–208 (2002).

Silva, J. et al. Establishment of histone h3 methylation on the inactive X chromosome requires transient recruitment of Eed-Enx1 polycomb group complexes. Dev. Cell 4, 481–495 (2003).

Goldenberg, R. L., Hauth, J. C. & Andrews, W. W. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1500–1507 (2000).

De Santa, F. et al. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell 130, 1083–1094 (2007).

Tong, M., Potter, J. A., Mor, G. & Abrahams, V. M. Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Human Fetal Membranes Induce Neutrophil Activation and Release of Vital Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. J. Immunol. 203, 500–510 (2019).

Li, Z. H. et al. Galectin-9 Alleviates LPS-Induced Preeclampsia-Like Impairment in Rats via Switching Decidual Macrophage Polarization to M2 Subtype. Front. immunology 9, 3142 (2018).

Racicot, K. et al. Type I Interferon Regulates the Placental Inflammatory Response to Bacteria and is Targeted by Virus: Mechanism of Polymicrobial Infection-Induced Preterm Birth. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 75, 451–460 (2016).

Cardenas, I. et al. Placental viral infection sensitizes to endotoxin-induced pre-term labor: a double hit hypothesis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 110–117 (2011).

Sela, H. Y. et al. Human trophectoderm apposition is regulated by interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10) during early implantation. Placenta 34, 222–230 (2013).

Graham, C. et al. In vivo immune signatures of healthy human pregnancy: Inherently inflammatory or anti-inflammatory? PLoS One 12, e0177813 (2017).

Saito, S., Nakashima, A., Shima, T. & Ito, M. Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 601–610 (2010).

Gnainsky, Y. et al. Biopsy-induced inflammatory conditions improve endometrial receptivity: the mechanism of action. Reproduction 149, 75–85 (2015).

Gnainsky, Y. et al. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil. Steril. 94, 2030–2036 (2010).

Koga, K., Aldo, P. B. & Mor, G. Toll-like receptors and pregnancy: trophoblast as modulators of the immune response. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 35, 191–202 (2009).

Dekel, N., Gnainsky, Y., Granot, I. & Mor, G. Inflammation and implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 17–21 (2010).

Dekel, N., Gnainsky, Y., Granot, I., Racicot, K. & Mor, G. The role of inflammation for a successful implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 72, 141–147 (2014).

Gomez-Lopez, N., Estrada-Gutierrez, G., Jimenez-Zamudio, L., Vega-Sanchez, R. & Vadillo-Ortega, F. Fetal membranes exhibit selective leukocyte chemotaxic activity during human labor. J. Reprod. immunology 80, 122–131 (2009).

Gomez-Lopez, N. et al. Evidence for a role for the adaptive immune response in human term parturition. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 69, 212–230 (2013).

Hamilton, S. A., Tower, C. L. & Jones, R. L. Identification of chemokines associated with the recruitment of decidual leukocytes in human labour: potential novel targets for preterm labour. PLoS one 8, e56946 (2013).

Osman, I. et al. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 9, 41–45 (2003).

Mor, G. Pregnancy Reconceived. Nat. History 116, 36–41 (2007).

Buhimschi, C. S. et al. Amniotic fluid angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, and soluble receptor tunica interna endothelial cell kinase-2 levels and regulation in normal pregnancy and intraamniotic inflammation-induced preterm birth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 3428–3436 (2010).

Combs, C. A. et al. Amniotic fluid infection, inflammation, and colonization in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 210, 125 e121–125 e115 (2014).

Daskalakis, G. et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-18 at mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis: relationship to intraamniotic microbial invasion and preterm delivery. BJOG: an. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 116, 1743–1748 (2009).

Negishi, H. et al. Correlation between cytokine levels of amniotic fluid and histological chorioamnionitis in preterm delivery. J. Perinat. Med. 24, 633–639 (1996).

Yoon, B. H. et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185, 1130–1136 (2001).

Andrews, W. W. et al. Early preterm birth: association between in utero exposure to acute inflammation and severe neurodevelopmental disability at 6 years of age. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198, 466 e461–466 e411 (2008).

Romero, R., Dey, S. K. & Fisher, S. J. Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765 (2014).

Luster, A. D., Unkeless, J. C. & Ravetch, J. V. Gamma-interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature 315, 672–676 (1985).

Loetscher, M. et al. Chemokine receptor specific for IP10 and mig: structure, function, and expression in activated T-lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 184, 963–969 (1996).

Gotsch, F. et al. Maternal serum concentrations of the chemokine CXCL10/IP-10 are elevated in acute pyelonephritis during pregnancy. J. maternal-fetal neonatal medicine: Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Medicine, Federation Asia Ocean. Perinat. Societies, Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 20, 735–744 (2007).

Gervasi, M. T. et al. Midtrimester amniotic fluid concentrations of interleukin-6 and interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10: evidence for heterogeneity of intra-amniotic inflammation and associations with spontaneous early (<32 weeks) and late (>32 weeks) preterm delivery. J. Perinat. Med. 40, 329–343 (2012).

Romero, R. et al. CXCL10 and IL-6: Markers of two different forms of intra-amniotic inflammation in preterm labor. American journal of reproductive immunology 78 (2017).

Le Ray, I. et al. Changes in maternal blood inflammatory markers as a predictor of chorioamnionitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Reprod. immunology 73, 79–90 (2015).

Norwitz E. R et al Molecular Regulation of Parturition: The Role of the Decidual Clock. In: Norwitz, D.W.B.a.E.R. (ed). Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, pp 1–20 (2015).

Kosaka, K. et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) activates monocytes to produce interleukin-8 via a different pathway from luteinizing hormone/HCG receptor system. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 5199–5208 (2002).

Wan, H. et al. Chorionic gonadotropin can enhance innate immunity by stimulating macrophage function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 926–933 (2007).

Tsampalas, M. et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin: a hormone with immunological and angiogenic properties. J. Reprod. immunology 85, 93–98 (2010).

Koldehoff, M. et al. Modulating impact of human chorionic gonadotropin hormone on the maturation and function of hematopoietic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 1017–1026 (2011).

Yu, S. et al. The regulation of Jmjd3 upon the expression of NF-kappaB downstream inflammatory genes in LPS activated vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 485, 62–68 (2017).

Brosens, J. J., Hayashi, N. & White, J. O. Progesterone receptor regulates decidual prolactin expression in differentiating human endometrial stromal cells. Endocrinology 140, 4809–4820 (1999).

Kwon, J.Y. et al. Relevance of placental type I interferon beta regulation for pregnancy success. Cell. Mol. Immunol. (2018).

Kaislasuo, J. et al. IL-10 to TNFalpha ratios throughout early first trimester can discriminate healthy pregnancies from pregnancy losses. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol., e13195 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants NICHD 5 K12HD047018-09; and NIAID 1R01AI145829-01. MS was further supported by the Albert McKern Scholar Award. We thank Dr. Yang Yang-Hartwich for her advice on the design of some of the experiments related to chip array.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. performed experiments, interpreted data, and assisted with preparation of the manuscript. Y.Y., R.R., E.G. and S.G., S.E., S.D., P.A. performed experiments. G.P. performed statistical analyses. S.S., L.P. and J.K. assisted with clinical samples. G.M. conceived and designed the study, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silasi, M., You, Y., Simpson, S. et al. Human Chorionic Gonadotropin modulates CXCL10 Expression through Histone Methylation in human decidua. Sci Rep 10, 5785 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62593-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62593-9

This article is cited by

-

Oxygen regulates ILC3 antigen presentation potential and pregnancy-related hormone actions

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2022)

-

Transcriptomic profiling of canine decidualization and effects of antigestagens on decidualized dog uterine stromal cells

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.