Abstract

The gut microbiota critically confers various health benefits, whereas environmental chemicals can affect its constitution and functionality thereby increasing disease risk. In the present study, we aim to evaluate the toxic effects of a wildly-used herbicide 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) on the gut microbiome and host using an occupationally relevant dose. A mouse model was used combined with metagenomic sequencing and metabolomic profiling to examine the alterations induced by subchronic low-dose 2,4-D exposure in fecal and plasma samples. The metagenomics results revealed a distinct gut microbial community with profound changes in diverse microbial pathways including urea degradation, amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism in 2,4-D-treated mice. Moreover, the metabolomics results revealed that the metabolic profiles in treatment group were differentiated from control group in both fecal and plasma samples. Toxic effects on the host of 2,4-D at an occupationally relevant dose were observed indicated by decreased acylcarnitine levels in plasma. These findings indicated that 2,4-D can cause toxicity and substantially impact the gut microbiome in mice at occupationally relevant doses, inferring that the relationship between environmental contaminants and microbiota is largely underestimated calling for more comprehensive consideration of the toxicity of occupational exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) has been commercialized as a herbicide since more than 70 years ago, and it is still one of the most wildly-used herbicides in the world including the United States1. More than 1000 products that are currently commercially available in the U.S. contain 2,4-D as an active ingredient2. 2,4-D mimics indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the main natural auxin, at molecular structure level resulting in uncontrolled growth, together with the induction of overproduction of reactive oxidative species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation, eventually leading to death in plants3,4. Generally, 2,4-D is quickly absorbed if ingested orally in mice and human, followed by rapid urinary excretion primarily as unchanged 2,4-D. It usually takes much longer for absorption with dermal exposure5. Proximal tubules of the kidney are responsible for the active excretion of 2,4-D, and dose-dependent toxicity ensues including adverse effects on the eye, kidney, thyroid, adrenals and testes or ovaries when the dose exceeds the renal clearance capacity6.

As one of the oldest and most successful herbicides, the toxic effects of 2,4-D to animals and human have been extensively studied although some results were inconsistent7,8. For oral administration, the lethal dose (LD50) of 2,4-D in mice is 138 mg/kg; in rats, depending on the chemical form LD50 values ranges from 639 mg/kg to 1646 mg/kg2. For dermal exposure, LD50 values ranges from 1829 mg/kg to higher than 2000 mg/kg in rabbits6. In addition, a subchronic NOEL (No Observable Effect Level) was established at 15 mg/kg body weight per day in rats and a subchronic NOAEL (No Observable Adverse Effect Level) was established at 15 mg/kg body weight per day in mice6. An ADI (Acceptable daily intake) of 0.01 mg/kg body weight was established based on the one-year toxicity study in dogs and two-year study in rats with the NOAEL of 1 mg/kg body weight per day using an uncertainty factor of 1005. 2,4-D generally degrades rapidly under most environmental conditions, with the half-life less than a week for most soil types; it also has rapid degradation in water under aerobic conditions5. Even with relatively low levels in the environment, human exposure to 2,4-D may occur through the direct contact with agricultural or residential areas after its application as a weed control agent.

Mounting evidence indicates that the gut microbiome is essential to host metabolism and physiology, and perturbations of the gut microbiome are associated with a number of human diseases9. It is well established that numerous environmental chemicals are able to induce unwanted alterations in the gut microbiome, for instance, heavy metals10,11, pesticides12,13, artificial sweeteners14,15,16, antibiotics17,18 and others19. More importantly, those environmentally-driven disturbance in the gut microbial community comprises an assemblage of microbial pathways and metabolites that may lead to adverse effects on the host. For example, 6-month saccharin exposure in mice enriched pro-inflammatory microbial pathways and metabolites in gut microbiome in concert with an elevation of inflammation mediators in mouse liver14. Likewise, diazinon-induced alterations in gut microbial pathways and metabolites regarding neurotransmitters might contribute to the neurotoxicity of diazinon12. As an environmental chemical that is extensively utilized on agriculture, home lawns and roadsides, it is imperative for the comprehensive examination of its possible harmful health effects including the impact on gut microbiome. However, the effects of 2,4-D on gut microbiome have not been properly investigated yet. Thus, we used a mouse model, which was utilized to study the microbiome-xenobiotics interactions in previous studies, to investigate the interactions between 2,4-D and the gut microbiome10,12,19. Furthermore, the dose used in this study for subchronic 2,4-D exposure is lower than the NOAEL reported in previous studies5, and is also occupationally relevant20. At this dose, we still observed strong toxicity on the host manifested by distinct plasma metabolite profiles, suggesting underestimated 2,4-D occupational toxicity.

The purpose of this study is to provide the first evidence regarding the impact on the host metabolic profiles and gut microbiome by subchronic low-dose 2,4-D exposure. To achieve this goal, we combined metagenomic and metabolomic approaches for the examination of 2,4-D induced alterations in mouse plasma and fecal samples. After 13-week 2,4-D exposure, a shifted gut microbial composition was revealed with a series of significantly differentiated species. Marked alterations of gut microbial gene repertoires were discovered, with enrichment of genes involved in urea degradation and perturbations in amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism, suggesting an altered functional role of the gut microbiome. In addition, metabolomic profiling of both fecal and plasma samples exhibited differentiated metabolic profiles between control and treatment groups, suggesting perturbations in host metabolism and gut microbial metabolic activities. These findings demonstrated that occupationally relevant exposure of 2,4-D is able to induce toxicity by altering the metabolic profiles in host plasma especially acylcarnitines; meanwhile, strong perturbations in gut microbiota were also induced with changes in its microbial composition, metabolic pathways and metabolites, suggesting that the interaction between environmental contaminants and microbiota is largely underestimated and providing new insights regarding mechanisms contributing to the toxicity of environmental agents.

Results

Diversity analysis and taxonomic characterization of 2,4-D perturbed gut microbiome

To investigate whether the mouse gut microbiome structure was disturbed by 2,4-D exposure, the gut microbial diversity and constitution were compared between treatment and control groups. Alpha diversities were measured and compared in the overall microbial community over the 13-week treatment course using the chao1 metric as shown in Fig. 1A. At 0 week, the alpha diversities showed no significant difference whereas the treatment group had significantly lower alpha diversities than control group at both 4 weeks and 13 weeks. The increase of alpha diversity in control group can be explained in view of the gut micro-ecosystem21. The chao1 index represents the richness of the gut microbial community. The richness of the gut microbiome would thrive in early life and gradually reach ecological saturation if not perturbed by intrinsic or extrinsic factors22,23, which accounts for the increase in alpha diversity in controls at 4 and 13 weeks. The reduction induced by 2,4-D exposure in alpha diversity indicates that the species richness, which was essential for the normal functional role of gut microbiota, was compromised by 2,4-D. Moreover, 13-week 2,4-D treatment substantially changed the gut microbial composition with diverse significantly-altered phyla and species. The phylum Acidobacteria was enriched in control group, whereas the phyla Bacteroidetes, Chlorobi, Chloroflexi, Spirochaetes and Thermotogae were enriched in treatment group (Fig. 1B). At the species level, the abundances of Streptomyces coelicolor, methylobacterium extorquens and Dehalococcoides ethenogenes were significantly higher in treatment group, whereas the abundances of Clostridium sp. 7_2_43FAA, Xylanimonas cellulosilytica, Cronobacter sakazakii, Escherichia coli, and Bacillus atrophaeus were significantly higher in control group (Fig. 1C). The alterations at both the phylum and species levels represented an interrupted microbial composition of the mouse gut microbiome after 2,4-D exposure.

(A) Comparison of alpha diversities in the gut microbial communities between 2,4-D and control groups at 0 week, 4 weeks and 13 weeks. (student’s t-test, n = 5). (B) Cladogram for taxonomic representation of significant differences in the gut microbial communities at phylum level. (p < 0.05 (Kruksal-Wallis test); LDA score ≥2; n = 5). (C) Gut microbial species that are significantly different between control and 2,4-D groups. (q < 0.05; n = 5).

Comparative metagenome analysis revealed pronounced differences in gut microbial functional pathways

The metagenomics RAST server24 (MG-RAST, version 4.03) was applied for the annotation of mouse gut metagenome to describe the metabolic features of the gut microbiome. SEED is a platform that provides consistent and accurate genome annotations25. SEED also includes subsystems, which stand for grouped biological functions together responsible for a specific biological pathway or structural complex26. The subsystems have 4 different levels based on classification levels. Figure 2 shows the gut microbial metabolic functions that were significantly changed by 13-week 2,4-D exposure. Of SEED subsystem level 2, the abundances of gut microbial genes involved in polysaccharides and alanine, serine, and glycine subsystems were significantly higher in treatment group, whereas the abundances of gut microbial genes involved in lysine, threonine, methionine, and cysteine, monosaccharides, choline bitartrate degradation, plant hormones and branched-chain amino acids subsystems were significantly higher in control group (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the heat map representing the distribution of gut microbial genes of SEED subsystem level 3 displayed a consistent clustering pattern among individuals in separate groups (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the marked distinction in microbial metabolic pathways demonstrates that 2,4-D exposure did alter the functionality of gut microbiome.

Specifically, the gut microbiome of the treatment group exhibited significant alterations to pathways involved in urea degradation, amino acid metabolism and carbohydrate utilization compared to control group (Figs 3, 4 and 5). The pathway abundances of urea decomposition and urease subunits were significantly increased in 2,4-D treated mouse gut microbiome. Moreover, at functional level, the microbial genes of urease alpha subunit, urease beta subunit and urease accessory protein UreG were significantly upregulated (Fig. 3). In addition, significant perturbations in microbial amino acid metabolism were found in treatment group compared to control group with significantly-altered gene abundance involved in the metabolism of glycine, arginine, methionine, aromatic amino acids and branched-chain amino acids (Fig. 4). Significant alterations in the microbial genes involved in carbohydrate utilization were also observed in mouse gut microbiome of the treatment group compared to control group. In particular, the utilization of monosaccharides (e.g. L-arabinose, L-fucose and L-rhamnose) decreased whereas the utilization of polysaccharides (e.g. cellulosome) increased supported by the downregulation and upregulation of a repertoire of microbial genes encoding related enzymes, respectively (Fig. 5).

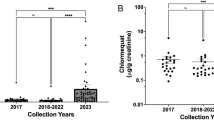

Alterations in the metabolic profiles of gut microbiome induced by 2,4-D exposure

To assess the impact of a shifted gut microbiome on its metabolic products, metabolomic profiling was performed on mouse fecal samples. Figure 6A illustrated that 2,4-D exposure changed the metabolic profiles of the mouse gut microbiome, with 6394 perturbed molecular features. Moreover, the metabolic profiles of treatment group were well-separated from control group using the first two components of PCA. (Fig. 6B, 64.3% and 15.4% variation were explained by PC1 and PC2, respectively). Together the data indicated that 2,4-D induced functional changes in the gut microbiome metabolic profiles. To further investigate the effects of the changes in the gut microbial metabolome, we identified 21 fecal metabolites that were significantly altered after 2,4-D exposure (Table S2). For instance, prostaglandins including delta-12-Prostaglandin J2 and prostaglandin-c2 were significantly more abundant in 2,4-D treatment mouse. In addition, nitrogen metabolites such as amino acids and their metabolic intermediates; purines, pyrimidines and their derivatives were also found to be differentiated, which supported that 2,4-D perturbed the nitrogen metabolism of mouse gut microbiome indicated by metagenomics results.

(A,C) Cloud plots representing 2,4-D exposure-perturbed metabolic profiles with molecular features being altered in mouse fecal and plasma samples, respectively. (n = 5). (B,D) Separations of the metabolite profiles between control and 2,4-D groups in mouse fecal and plasma samples, respectively. (n = 5).

Changes in host plasma metabolome after 2,4-D exposure

Host metabolomic profiles were assessed using mouse plasma samples. After 13-week 2,4-D exposure, the metabolic profiles were differentiated in mouse plasma between control and treatment groups. PCA analysis shows that the metabolic profiles of the two groups were almost separated (Fig. 6D, 63.2% and 24.8% variation were explained by PC1 and PC2, respectively). Furthermore, 1074 molecular features were perturbed in 2,4-D-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 6C). We identified 17 perturbed metabolites in the plasma (Table S1). Of interest, the levels of a class of metabolites known as acylcarnitines were significantly lower in mice with 2,4-D treatment (Table 1). The distinct metabolic profiles in the plasma of 2,4-D-treated mice especially with a series of lower-level acylcarnitines indicated the toxic effects of subchronic 2,4-D exposure at an occupationally relevant dose.

Discussion

The mechanisms of 2,4-D toxicity in animals and human are not quite definite and oxidative stress may be one of them27,28,29,30. In the present study, metagenomic sequencing and metabolomic profiling were applied to examine the impact of subchronic low-dose 2,4-D exposure on the host and gut microbiome. Clearly, the host metabolic profiles were differentiated by 2,4-D exposure indicating low-dose toxicity. Meanwhile, the results also demonstrate that 2,4-D perturbed not only the composition and diversity, but also functional pathways and metabolic profiles of the gut microbiota. Accumulating evidence suggests that the alterations of microbiome-related pathways and metabolites would lead to a disturbed gut-host homeostasis hence increasing disease risk18. For example, perturbations in gut microbial metabolic activities involved in protein fermentation and amino acid metabolism can lead to the elevation of toxic metabolites such as polyamines, hydrogen sulphide and ammonia, which play an role in the progression of colorectal cancer by inducing inflammation, ROS production, or genotoxicity31. Likewise, microbiome-derived uremic toxins such as p-cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate resulting from gut dysbiosis are associated with chronic kidney disease32,33. Given the strong association between gut microbiome perturbations and a variety of human diseases coupled with the capacity of 2,4-D to induce gut microbiome alterations, the findings of the present study might provide insights regarding the mechanistic basis by which 2,4-D adversely affects human health.

One of the intriguing findings from our study was that 2,4-D induced remarkable abundance changes in gut microbial pathways and gene families. We found 35 microbial pathways (Level 3 Subsystems) and 82 microbial genes (Functional Level Subsystems) at significantly different abundances in the treatment group compared to control group. A reduction of genes involved in plant hormones was observed in mouse gut microbiome after 2,4-D exposure (Fig. 2A). Even though plant hormone-related pathways do not exist in animals and human, they are commonly present in gut bacteria. Thus, the alterations to bacterial metabolic activities and products resulting from the impact of 2,4-D on plant hormone metabolism may indirectly affect host health, which contradicts the notion that certain environmental chemicals are safe to human just because their targeting pathways are not found in the human body. We also discovered a consistent enrichment of pathways and genes involved in urea degradation in treatment group compared to control group (Fig. 3). It is estimated that almost up to one third of urea produced endogenously by human body is degraded by microbial urease34. More importantly, microbial urease has been recognized as a virulence factor for gastrointestinal pathogenesis35. In addition, a significant shift in gene abundances of microbial amino acid metabolism as well as carbohydrate metabolism occurred in the gut microbiome of 2,4-D treated mice. To be more specific, for amino acids, the metabolism of alanine, serine, and glycine was enhanced whereas lysine, threonine, methionine, cysteine and branched-chain amino acids was diminished; for carbohydrates, the metabolism of polysaccharides was enhanced whereas monosaccharides was diminished. Together this may indicate the change of utilization preference in amino acids and carbohydrates in the 2,4-D-altered gut microbial community, and evidence shows that microbial amino acids and carbohydrate metabolism can influence host amino acid and energy homeostasis, respectively36,37. Therefore, the fundamental metabolism and the functional role of the gut microbiome were different in 2,4-D-treated mice compared to controls due to changes in diverse microbial metabolic pathways and functions.

A less resilient gut microbial community indicated by a lower alpha diversity along with a variety of shifted gut microbial species was found in mice treated with 2,4-D (Fig. 1). The relative abundances of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes increased in the gut microbiome of treatment group compared to control group. Dehalococcoides ethenogenes has been shown to play a major role in the degradation of chlorinated hydrocarbons in contaminated environments38,39. It is suggested that Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 has the dehalogenation potential to a diversity of chlorinated hydrocarbons based on up to 17 putative dehalogenase gene homologues found in its genome40. Thus, the enrichment of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes in 2,4-D-treated mouse gut microbiome likely reflects the selective pressure exerted by 2,4-D in the gut environment, and the competitive advantage held by Dehalococcoides ethenogenes resulting from its dehalogenation ability. In addition, an increased bacterial population in Phylum Spirochaetes has been found to be associated with 2,4-D exposure. Many members from Phylum Spirochaetes are involved in prevalent pathogenic diseases, such as Brachyspira pilosicoli and Brachyspira aalborgi in human intestinal spirochaetosis41, and Leptospira genus in Leptospirosis42. Various Spirochaetes species are also associated with the development of dementia and could be involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease43.

The communication between the gut microbiota and host through production of gut metabolites is one essential aspect of the gut-host cross-talk. On one hand, the gut microbial profiles are under regulations of host-produced metabolites, for instance, antimicrobial peptides44. On the other hand, gut microbiome-derived metabolites can contribute to the rise of either host fitness or disease risk45. For example, the gut microbiome is an important source for vitamins such as vitamin K, vitamin B12, biotin, folate and so forth22,46. Meanwhile, trimethylamine N-oxide, derived from the gut bacterial metabolite trimethylamine, is highly correlated with cardiovascular disease and kidney disease47. In the present study, we discovered distinct gut metabolic profiles between treatment and control groups, demonstrating the capacity of 2.4-D to alter the metabolic functions and metabolite fingerprints in the gut microbiome. Prostaglandins were found to be enriched in fecal samples after 2,4-D exposure in mice. Prostaglandins are a class of lipid autacoids involved in inflammatory response48, which can be found in intestinal mucosa49. It is speculated that the increase of prostaglandins might be one of the coping strategies with gut inflammation. However, the mechanisms by which the abundances of prostaglandins being elevated and the physiological effects on host are unknown and merit further studies. We also found significant perturbations in nitrogen metabolites in the gut microbiome. In concert with the alterations in gene abundances of amino acid metabolism, differentiated metabolites including several amino acids and their metabolic intermediates supported that 2,4-D treatment induced functional alterations in gut microbial amino acid metabolism. Additionally, the differences in purines, pyrimidines and their derivatives also indicated a perturbed nitrogen metabolism. Taken together, the alterations in the metabolite profiles of mouse fecal samples testify to 2,4-D-induced functional changes in the mouse gut microbiome.

Furthermore, the metabolite profiles in host plasma were differentiated by 13-week low-dose 2,4-D treatment, suggesting the capability of low-dose 2,4-D exposure to directly or indirectly impact host metabolism. In particular, the plasma levels of a series of acylcarnitines were observed to be significantly lower in 2,4-D-treated mice. The NOAEL for subchronic (13-week) exposure of 2,4-D in mice is 15 mg/kg body weight per day according to previous studies5, which is equivalent to 90 ppm 2,4-D in drinking water using the daily water intake as 8 ml per 30 g body weight50. The dose used in the present study was approximately 60 times lower. However, strong toxic effects of 2,4-D manifested by marked perturbations in the host plasma acylcarnitine levels were observed at this very low dose, indicating that the 2,4-D toxicity can be exerted at doses that are far lower than NOAEL. In this context, acylcarnitines have never been associated with 2,4-D exposure and/or 2,4-D toxicity before. Acylcarnitines are involved in the beta-oxidation of fatty acids51, and the alterations in the plasma levels of acylcarnitines suggested perturbations in the fatty acid beta-oxidation pathway. It is reported that the daily doses of 2,4-D exposure in professional turf applicators were predicted to be up to 20 mg per day, which is comparable to the dose in the present study20. Thus, monitoring the changes of plasma acylcarnitine levels could help to identify occupational toxicity of 2,4-D. In addition, growing evidence suggests an important role that acylcarnitines play in neurological diseases52. For instance, a decrease of serum acylcarnitines is reported to be associated with neurological disorders including Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease53,54. Thus, lower levels of plasma acylcarnitines observed in 2,4-D-treated mice may be associated with the potential neurotoxicity of 2,4-D. Although the link between 2,4-D-induced gut microbiome perturbations and low plasma acylcarnitines cannot be built based on the results of the present study, clear correlations could be identified between the perturbed gut microbial species, Xylanimonas cellulosilytica and plasma acylcarnitine levels (Fig. S1). The association between low-dose 2,4-D exposure-induced gut microbiome perturbations and lower plasma acylcarnitine levels provided novel insights upon the mechanisms for 2,4-D toxicity, and the plasma acylcarnitines can serve as a novel biomarker for 2,4-D toxicity at low doses.

Despite the relatively limited sample size in this study, the results clearly demonstrated the capacity of 2,4-D to induce both phylogenetic and functional changes in mouse gut microbiome with differentiated metabolic profiles. Significant distinction was also shown in host plasma metabolic profiles indicating perturbations in host metabolism, even though direct causal effects of 2,4-D-disturbed gut microbiome on host metabolic outcomes cannot be inferred from the present study. Ours is the first study to investigate the impact on the gut microbiome by 2,4-D exposure using multi-omics approaches, the interplay between the alterations in microbial pathways and metabolites and their resultant health effects on host warrants further investigation.

To conclude, this is the first study that demonstrated the alterations in the gut microbiome driven by subchronic low-dose 2,4-D exposure. The metagenomics indicated significant perturbations by 2,4-D to the gut microbial composition and functionality, in concert with distinct metabolic profiles in mouse fecal samples revealed by metabolomics. Meanwhile, the metabolomic profiling of host plasma samples revealed altered host metabolic profiles suggesting 2,4-D toxicity at occupationally relevant doses. These findings support the notion that the homeostasis of gut microbiome can be readily impacted by environmental chemicals, suggesting reconsideration for the health effects and toxicity of wildly-used chemicals including 2,4-D.

Methods

Animals and exposure

Specific-pathogen-free (SPF) C57BL/6 male mice (~8 weeks of age), purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), were housed in the animal facility of University of Georgia. The environmental conditions were maintained as 22 °C temperature, 40–70% humidity, and a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle. All experiments were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Water and standard pelleted rodent diet ad libitum were provided for 1 week for their acclimation before 2,4-D treatment. After 1 week of acclimation, a control (n = 5) and treatment (n = 5) group were then randomly assigned. For the 2,4-D exposure, 1ppm 2,4-D (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) water solution (the concentration used in the present study is lower than NOAEL, i.e., 15 mg/kg of body weight per day5) was administered to the mice in the treatment group replacing tap water while the mice in the control group received tap water over the course of 13 weeks. Regular monitoring for health conditions was done twice a week. The mice were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. Before sacrifice, each mouse was placed in an individual cage for fecal sample collection, and the feces were immediately put into liquid nitrogen for snap freezing. Fecal samples were collected individually for both groups at the time points including 0 week, 4 weeks and 13 weeks; plasma samples were collected during necropsy; and the samples were kept at −80 °C after harvest until further analysis.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and diversity analysis

16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed as previously described in Lu et al.10. Briefly, microbial DNA was extracted from mouse fecal pellets using the PowerSoil® DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Then the DNA was amplified using 515 (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) and 806 (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) primers55 targeting the V4 regions of 16S rRNA gene in bacteria. After normalization, individual samples were barcoded and finally pooled for the construction of the sequencing library. The quantification of DNA was performed using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), and the DNA was sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq (500 cycles v2 kit) in the Georgia Genomics Facility of University of Georgia. Paired reads were then assembled using Geneious 8.15 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand). Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) picking and diversity analysis were conducted using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME, version 1.9.1).

Comparative metagenomic analysis

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing was performed as previously described in Gao et al.12. Briefly, fecal DNA (10 ng/µL) was fragmented using the Bioruptor UCD-300 sonication device. The Kapa Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems) was applied to construct the sequencing library according to manufacturer’s instructions. The quantification of DNA was performed using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). The sequencing was performed using the Illumina NextSeq High Output Flow Cell (300 Cycles; PE150) in the Georgia Genomics Facility of University of Georgia. The MG-RAST metagenomics analysis sever (http://metagenomics.anl.gov, version 4.0.3) was applied for the taxonomic and functional analysis with RefSeq and Subsystems databases, respectively24.

Sample processing for metabolomics

For fecal samples, 20 mg feces and 50 mg glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) were added to 400 µL cooled methanol solution (methanol: water 1: 1), followed by homogenizing using a TissueLyser (QIAGEN) for 15 min at 50 Hz. The supernatant was collected after centrifuging for 10 min at 1,2000 rpm, dried up in a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific), and then resuspended for metabolomic profiling. For plasma samples, 80 µL cooled methanol was added to 20 µL plasma. After incubation for 30 min at −20 °C, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,2000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, dried up in a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific), and then resuspended.

Metabolomic profiling and metabolite identification

LC-MS analysis was performed on a quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-TOF) 6550 mass spectrometer (Aglient Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with an electrospray ionization source. The mass spectrometer was interfaced with an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UPLC system (Aglient Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Metabolites were analyzed in the positive mode over a m/z range of 50–1000 with a C18 T3 reverse-phased column (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). MS/MS data were generated on the Q-TOF for the identification of perturbed metabolites. The XCMS Online sever (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu, version 3.5.1) was applied for peak picking, alignment, integration, and extraction of the peak intensities. A two-tailed Welch’s t-test was used for the assessment of metabolite differences between control and treatment groups. The programs of MS-DIAL56 (version 2.70) and MS-FINDER57 (version 2.20) were used for the identification of metabolites.

Statistical analysis of data

Alpha rarefaction was performed using chao1 metric via QIIME. Also, cladogram for taxonomic representation of significant differences was generated using LefSe58. Principle component analysis (PCA) was applied to examine the intrinsic clusters of metabolomics data. In addition, heatmaps were generated using a hierarchical clustering algorithm to visualize the comparison of gene abundances. The metagenomic sequence count data for both taxonomic and functional analysis were processed using DESeq259 for statistics analysis, and the result was considered to be significant if q-value < 0.05 (adjusted for the false discovery rate).

Ethics approval

The animal experiment was approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Data Availability

Data is available through http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB21490 with project accession #PRJEB21490.

References

Peterson, M. A., McMaster, S. A., Riechers, D. E., Skelton, J. & Stahlman, P. W. 2, 4-D past, present, and future: a review. Weed Technology 30, 303–345 (2016).

Jervais, G., Luukinen, B., Buhl, K. & Stone, D. 2,4-D General Fact Sheet. National Pesticide Information Center, Oregon State University Extension Services, http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/24Dgen.html (2008).

Song, Y. Insight into the mode of action of 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D) as an herbicide. Journal of integrative plant biology 56, 106–113 (2014).

Islam, F. et al. 2, 4-D attenuates salinity-induced toxicity by mediating anatomical changes, antioxidant capacity and cation transporters in the roots of rice cultivars. Scientific Reports 7 (2017).

WHO. 2, 4-D in drinking-water. Background document for preparation of WHO Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Geneva, World Health Organization (WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/70) (2003).

Jervais, G., Luukinen, B., Buhl, K. & Stone, D. 2,4-D Technical Fact Sheet. National Pesticide Information Center, Oregon State University Extension Services, http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/archive/2,4-DTech.html (2008).

Munro, I. C. et al. A comprehensive, integrated review and evaluation of the scientific evidence relating to the safety of the herbicide 2, 4-D. Journal of the American College of Toxicology 11, 559–664 (1992).

Garabrant, D. H. & Philbert, M. A. Review of 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2, 4-D) epidemiology and toxicology. Critical reviews in toxicology 32, 233–257 (2002).

Tremaroli, V. & Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489, 242–249 (2012).

Lu, K. et al. Arsenic exposure perturbs the gut microbiome and its metabolic profile in mice: an integrated metagenomics and metabolomics analysis. Environmental health perspectives 122, 284 (2014).

Chi, L. et al. The Effects of an Environmentally Relevant Level of Arsenic on the Gut Microbiome and its Functional Metagenome. Toxicological Sciences (2017).

Gao, B., Bian, X., Mahbub, R. & Lu, K. Sex-specific effects of organophosphate diazinon on the gut microbiome and its metabolic functions. Environmental health perspectives 125, 198 (2017).

Gao, B. et al. Editor’s Highlight: OrganophosphateDiazinon Altered Quorum Sensing, Cell Motility, Stress Response, and Carbohydrate Metabolism of Gut Microbiome. Toxicological Sciences 157, 354–364 (2017).

Bian, X. et al. Saccharin induced liver inflammation in mice by altering the gut microbiota and its metabolic functions. Food and Chemical Toxicology (2017).

Bian, X. et al. Gut Microbiome Response to Sucralose and Its Potential Role in Inducing Liver Inflammation in Mice. Frontiers in physiology 8, 487 (2017).

Suez, J., Korem, T., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Segal, E. & Elinav, E. Non-caloric artificial sweeteners and the microbiome: findings and challenges. Gut microbes 6, 149–155 (2015).

Cho, I. et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature 488, 621–626 (2012).

Cho, I. & Blaser, M. J. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 13, 260–270 (2012).

Claus, S. P., Guillou, H. & Ellero-Simatos, S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2, 16003 (2016).

Harris, S. A., Sass-Kortsak, A. M., Corey, P. N. & Purdham, J. T. Development of models to predict dose of pesticides in professional turf applicators. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 12, 130 (2002).

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220 (2012).

Koenig, J. E. et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 4578–4585 (2011).

Yatsunenko, T. et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. nature 486, 222 (2012).

Meyer, F. et al. The metagenomics RAST server–a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC bioinformatics 9, 386 (2008).

Overbeek, R. et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic acids research 42, D206–D214 (2013).

Overbeek, R. et al. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic acids research 33, 5691–5702 (2005).

Oruc, E. O., Sevgiler, Y. & Uner, N. Tissue-specific oxidative stress responses in fish exposed to 2, 4-D and azinphosmethyl. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 137, 43–51 (2004).

Abdollahi, M., Ranjbar, A., Shadnia, S., Nikfar, S. & Rezaiee, A. Pesticides and oxidative stress: a review. Medical Science Monitor 10, RA141–RA147 (2004).

Tayeb, W., Nakbi, A., Trabelsi, M., Miled, A. & Hammami, M. Biochemical and histological evaluation of kidney damage after sub-acute exposure to 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic herbicide in rats: involvement of oxidative stress. Toxicology mechanisms and methods 22, 696–704 (2012).

Matviishyn, T. M., Kubrak, O. I., Husak, V. V., Storey, K. B. & Lushchak, V. I. Tissue-specific induction of oxidative stress in goldfish by 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid: mild in brain and moderate in liver and kidney. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 37, 861–869 (2014).

Louis, P., Hold, G. L. & Flint, H. J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Microbiology 12, 661–672 (2014).

Ramezani, A. & Raj, D. S. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, ASN. 2013080905 (2013).

Nallu, A., Sharma, S., Ramezani, A., Muralidharan, J. & Raj, D. Gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease: challenges and opportunities. Translational Research 179, 24–37 (2017).

Walser, M. & Bodenlos, L. J. Urea metabolism in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation 38, 1617 (1959).

Mora, D. & Arioli, S. Microbial urease in health and disease. PLoS pathogens 10, e1004472 (2014).

Neis, E. P., Dejong, C. H. & Rensen, S. S. The role of microbial amino acid metabolism in host metabolism. Nutrients 7, 2930–2946 (2015).

Flint, H. J., Bayer, E. A., Rincon, M. T., Lamed, R. & White, B. A. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 6, 121–131 (2008).

Adrian, L., Szewzyk, U., Wecke, J. & Görisch, H. Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes. Nature 408, 580–583 (2000).

Bunge, M. et al. Reductive dehalogenation of chlorinated dioxins by an anaerobic bacterium. Nature 421, 357–360 (2003).

Fennell, D. E., Nijenhuis, I., Wilson, S. F., Zinder, S. H. & Häggblom, M. M. Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 reductively dechlorinates diverse chlorinated aromatic pollutants. Environmental science & technology 38, 2075–2081 (2004).

Amat, V. I. et al. Colonic spirochetes: an infrequent cause of adult diarrhea. Gastroenterologia y hepatologia 27, 21–23 (2004).

Bharti, A. R. et al. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet infectious diseases 3, 757–771 (2003).

Miklossy, J. Alzheimer’s disease-a neurospirochetosis. Analysis of the evidence following Koch’s and Hill’s criteria. Journal of neuroinflammation 8, 90 (2011).

Bevins, C. L. & Salzman, N. H. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 9, 356–368 (2011).

Nicholson, J. K. et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 336, 1262–1267 (2012).

Said, H. M. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins in health and disease. Biochemical Journal 437, 357–372 (2011).

Zeisel, S. H. & Warrier, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO), the Microbiome, and Heart and Kidney Disease. Annual Review of Nutrition 37 (2017).

Ricciotti, E. & FitzGerald, G. A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 31, 986–1000 (2011).

Hawkey, C. & Rampton, D. Prostaglandins and the gastrointestinal mucosa: are they important in its function, disease, or treatment? Gastroenterology 89, 1162–1188 (1985).

Bachmanov, A. A., Reed, D. R., Beauchamp, G. K. & Tordoff, M. G. Food intake, water intake, and drinking spout side preference of 28 mouse strains. Behavior genetics 32, 435–443 (2002).

Reuter, S. E. & Evans, A. M. Carnitine and acylcarnitines. Clinical pharmacokinetics 51, 553–572 (2012).

Jones, L. L., McDonald, D. A. & Borum, P. R. Acylcarnitines: role in brain. Progress in lipid research 49, 61–75 (2010).

Saiki, S. et al. Decreased long-chain acylcarnitines from insufficient β-oxidation as potential early diagnostic markers for Parkinson’s disease. Scientific Reports 7 (2017).

Cristofano, A. et al. Serum Levels of Acyl-Carnitines along the Continuum from Normal to Alzheimer’s Dementia. PloS one 11, e0155694 (2016).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. The ISME journal 6, 1621–1624 (2012).

Tsugawa, H. et al. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nature methods 12, 523–526 (2015).

Tsugawa, H. et al. Hydrogen rearrangement rules: computational MS/MS fragmentation and structure elucidation using MS-FINDER software. Analytical chemistry 88, 7946–7958 (2016).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome biology 12, R60 (2011).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 15, 550 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The University of Georgia, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the NIH/NIEHS provided partial financial support (R01ES024950) for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by K.L. and H.R. The animal experiment and other laboratory work was conducted by B.G., X.B., L.C., Y.L. and P.T. P.T. conducted the bioinformatics analysis. P.T., K.L., H.R. and B.G. wrote the paper. All authors read an approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, P., Gao, B., Chi, L. et al. Subchronic low-dose 2,4-D exposure changed plasma acylcarnitine levels and induced gut microbiome perturbations in mice. Sci Rep 9, 4363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40776-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40776-3

This article is cited by

-

Insufficient risk assessment of herbicide-tolerant genetically engineered soybeans intended for import into the EU

Environmental Sciences Europe (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.