Abstract

The aim of treating childhood cancer remains to cure all. As survival rates improve, long-term health outcomes increasingly define quality of care. The International Childhood Cancer Outcome Project developed a set of core outcomes for most types of childhood cancers involving relevant international stakeholders (survivors; pediatric oncologists; other medical, nursing or paramedical care providers; and psychosocial or neurocognitive care providers) to allow outcome-based evaluation of childhood cancer care. A survey among healthcare providers (n = 87) and online focus groups of survivors (n = 22) resulted in unique candidate outcome lists for 17 types of childhood cancer (five hematological malignancies, four central nervous system tumors and eight solid tumors). In a two-round Delphi survey, 435 healthcare providers from 68 institutions internationally (response rates for round 1, 70–97%; round 2, 65–92%) contributed to the selection of four to eight physical core outcomes (for example, heart failure, subfertility and subsequent neoplasms) and three aspects of quality of life (physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive) per pediatric cancer subtype. Measurement instruments for the core outcomes consist of medical record abstraction, questionnaires and linkage with existing registries. This International Childhood Cancer Core Outcome Set represents outcomes of value to patients, survivors and healthcare providers and can be used to measure institutional progress and benchmark against peers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Most children and adolescents receiving modern cancer therapy survive at least 5 years beyond diagnosis1,2,3. Substantial reductions in mortality over the past decades have been reached through therapeutic progress and improved supportive care4. Despite these promising results, survival rates remain poor for specific childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer types, such as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia2. In addition, if a cure is achieved, it is often compromised by adverse physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive effects that may substantially impact quality of life5,6,7,8,9. Prevention, identification and timely treatment of these adverse health outcomes among patients and survivors is one of the main pillars of supportive and follow-up care10,11.

Contemporary treatment regimens and follow-up strategies aim not only to achieve survival but also to optimize the quality of survival. Improved quality of care is evident when survival increases without a concurrent increase in adverse health outcomes, or when the occurrence of unfavorable health effects is reduced with similar or increased survival rates. We advocate that measurement of outcomes that are valued by patients, rather than monitoring processes and structures of care (such as complete and timely documentation or the availability of dedicated facilities or staff), should be used to define and promote high-quality care12,13,14. Through measurement of these outcomes, institutions can gain insight about their progress in treating childhood cancer, or identify best practices by benchmarking with their peers. The rapid digitization of society and healthcare systems, and the implementation of electronic health records, have accelerated the routine measurement and collection of data in medical settings. Harmonization of which outcomes to measure, compare and improve remains essential to draw meaningful conclusions and make an impact on the quality of care.

Pediatric cancers, which include many rare subtypes with a substantial collective health burden, could particularly benefit from international standardization of outcome measures. Core sets of patient-relevant outcomes have recently been defined and implemented for a range of other populations and disease types, including several adult cancers15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Similar initiatives are emerging in pediatrics23 and within pediatric oncology—for example, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and brain tumors24,25,26,27. Although evidence-based surveillance guidelines are available to define optimum care for the individual with or survivor of childhood cancer28,29, metrics to evaluate the quality of care from diagnosis into survivorship have not been established. A well-defined core outcome set for common types of childhood cancer provides a much needed metric to assess quality of care during and after treatment through the evaluation of patient-relevant outcomes.

The International Childhood Cancer Outcome Project developed the International Childhood Cancer Core Outcome Set derived from the perspectives of those who have survived childhood cancer and international healthcare providers. This core set represents physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes for each of 17 common childhood cancer subtypes.

The International Childhood Cancer Outcome Project consisted of three steps, from the starting point of 17 candidate outcome lists (step 1) to the selection of 17 core sets (step 2) with measurement instruments (step 3). Step 1, preparation, included a survey among healthcare providers from 17 professional backgrounds and focus groups of survivors. Step 2, outcome selection, included two Delphi rounds involving 435 (round 1) and 368 (round 2) international healthcare providers, finalized by a feedback round. Step 3, future implementation, included the selection of measurement instruments derived from the Delphi definitions by the project group, with consultation of topic experts. HCPs, healthcare providers.

These three circles represents the core outcomes included in the International Childhood Cancer Core Outcome Set, presented separately for central nervous system tumors, hematological malignancies and solid tumors. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; GvHD, graft-versus-host disease; HGG, high-grade glioma; Hodgkin, Hodgkin lymphoma; HP, hypothalamic–pituitary; LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; LGG, low-grade glioma; non-Hodgkin, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NRSTS, nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma; QoL, quality of life; RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma; SMN, subsequent malignant neoplasm (including meningioma).

Methods

The International Childhood Cancer Outcome Project was coordinated by a project group with representatives from the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology in The Netherlands (the Princess Máxima Center) and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in the USA (St Jude) and survivor representatives. Project participants included individuals who survived childhood cancer and a wide variety of healthcare providers internationally (Supplementary Table 1).

We initially focused on defining a unique core set of 5–10 clinically relevant outcomes for each of 17 childhood cancer subtypes representing common hematological malignancies (acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis), central nervous system tumors (low-grade glioma, high-grade glioma, embryonal tumor of the central nervous system and craniopharyngioma) and solid tumors (neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma, liver tumor, kidney tumor and extracranial germ cell tumor). Clinical relevance was defined as having a physical, psychosocial or neurocognitive influence on daily life and persisting for or developing two or more years after therapy. Acute toxicities and palliative outcomes were considered to be outside the scope of the project. Moreover, we decided that overall survival and cause-specific mortality should be a part of each core set; therefore, these factors were not included in the selection and prioritization process51.

A mixed methods approach consisting of the following three steps was used (Fig. 1): (1) preparation, (2) outcome selection and (3) future implementation.

Step 1: preparation

As a starting point for the prioritization process, potentially relevant outcomes for each of the 17 childhood cancer types were collected at the Princess Máxima Center through a survey among healthcare providers and focus groups of individuals who survived childhood cancer. Institutional approval for performing the focus groups was given by the Clinical Research Committee on 3 November 2020 with a waiver of further medical ethical review because the study was not considered to be subject to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Humans Act (WMO).

The clinical, nursing and paramedic staff at the Princess Máxima Center nominated 90 healthcare providers based on their expertise in the field to participate in an online survey (97% response rate; Supplementary Table 2). Together, they represented 17 professional backgrounds: pediatric oncologists; radiation oncologists; pain specialists; supportive care, symptom control or palliative care experts; late-effects physicians; nurses; advanced nurse practitioners; physical therapists; psychologists; neuropsychologists; medical social workers; child life specialists; pediatric neurologists; pediatric neurosurgeons; pediatric surgeons; pediatric endocrinologists and a pediatric oncologist with additional expertise in allogeneic transplants. Participants were asked to identify five to ten clinically relevant outcomes in any domain for a specific childhood cancer type as an open-ended question.

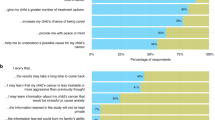

Four online focus groups were organized for survivors: one each for adults (≥18 years) with a history of a childhood hematological malignancy (six participants), central nervous system tumor (six participants) or solid tumor (seven participants), and a separate focus group for adolescents (12–18 years; two participants diagnosed with brain tumors and one with osteosarcoma) (Supplementary Table 3). We hypothesized teenagers might experience different issues in daily life which would be shared more easily among peers. We did not organize focus groups for parents because the parent and survivor representatives included in the project group anticipated a risk of caregiver reporting bias compared with the self-reports of survivors, an observation supported by recent publications33. Perspectives of younger patients and survivors were solicited during the adolescent focus group33. Inclusion criteria consisted of being age 12 years or older; being a 5-year survivor of a hematological malignancy, central nervous system tumor or solid tumor; and providing signed informed consent by the participant (if age ≥16 years) or both participant and legal guardian (if age <16 years). The exclusion criterion was lack of Dutch language fluency. Participants were recruited through flyers at the late-effects clinic, social media announcements or nomination by their healthcare provider. We aimed for eight to ten participants per focus group to provide optimum data richness and conversational flow52. The sessions were hosted digitally at the Princess Máxima Center in collaboration with the Dutch Childhood Cancer Organization using videoconferencing software and online tools (that is, Mentimeter and Padlet).

Subsequently, the collected outcomes from the healthcare provider surveys and survivor focus groups were extracted and harmonized by two researchers (R.L.M. and R.J.v.K.), with any discrepancies being resolved through discussion with a third party (L.C.M.K.) and with final agreement of the project group. These outcomes informed the unique candidate outcome lists that were established for each of the 17 childhood cancer types and served as the starting point for the outcome prioritization.

Step 2: outcome selection

To develop the core outcome set, including outcome definitions, we performed two Delphi rounds for 17 childhood cancer types. Both rounds were hosted electronically on the Welphi platform (www.welphi.com). Participants included healthcare providers at the Princess Máxima Center that participated in the healthcare provider survey (step 1), staff at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital who were nominated by the project group and leading international experts identified by working groups at the Princess Máxima Center and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. All participants were categorized into three stakeholder groups (pediatric oncologists, other (medical, nursing or paramedical) care providers, and psychosocial or neurocognitive care providers; Supplementary Table 1). Survivors of childhood cancer did not participate in the Delphi rounds because survivor representatives expressed concerns that prioritizing outcomes on the individual level might be too complex and could cause psychological distress. However, the intermediate results and final core sets were reviewed and approved by the survivor representatives in the project group.

With the first Delphi round in March and April 2021, we aimed to condense the candidate outcome list to 15–20 outcomes per childhood cancer type and add missing outcomes. For each of the candidate outcomes, participants were asked to rate the prevalence and severity on a one to seven Likert scale32. In addition, participants selected one most important outcome to include in the core set and could suggest new outcomes.

Outcomes were moved forward to the second Delphi round if one or both of the following criteria were met: (1) a median severity of the outcome of ≥6.0 in at least one of the stakeholder groups, and median prevalence of the outcome being greater than or equal to the median prevalence score across all participants in that same stakeholder group; and/or (2) top ranking, that is, ≥10% of participants within a stakeholder group considered the outcome the most important outcome to include in a core outcome set. If this resulted in a selection of less than 15 outcomes, the severity threshold would be decreased in steps of 0.5 until at least 15 outcomes were selected. New outcomes were added to the candidate outcome list if mentioned by two or more participants within the same type of childhood cancer.

All participants of the first Delphi round were also invited for the second Delphi round in May 2021, including nonresponders, provided they expressed an interest to participate. The results of the previous round were presented to the participants by e-mail.

This second iteration aimed to prioritize approximately five outcomes per childhood cancer type and to refine the outcome definitions. Participants were asked to rate the importance of including each outcome in a core set of five outcomes on a one to seven Likert scale, and select the three most important outcomes per childhood cancer type32.

Outcomes were prioritized by the following two criteria: (1) median score of ≥6.0 or higher in at least one of the stakeholder groups, and being selected by ≥25% as one of the top three outcomes in that same stakeholder group; or (2) a median score of ≥6.0 among all participants. To establish the degree of consensus, three levels of agreement were defined according to these criteria: level A (both criteria fulfilled), B (only the first criterion fulfilled) and C (only the second criterion fulfilled). For the four central nervous system tumors (low-grade glioma, high-grade glioma, embryonal tumors of the central nervous system and craniopharyngioma), we observed that the psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes were more highly prioritized than the physical outcomes. This would lead to exclusion of most of the latter outcomes if following the standard selection criteria. To improve the balance in these four Delphi surveys, we lowered the median score threshold for criterion (1) and (2) to 5.0 for the physical outcomes in these surveys, while also including the psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes based on the regular criteria. Outcomes with level A agreement, the highest level, were always included in the core set. Level B and C outcomes were included based on evidence presented in long-term follow-up guidelines and expert opinion within the project group. The final core sets and definitions were endorsed by the Delphi participants in an e-mail feedback round.

Draft definitions for each of the selected outcomes were developed by the project group, using the criteria for clinical relevance and a threshold where the patient experiences symptoms or an impact on daily life (for example, need to change lifestyle or use medication). Existing frameworks were used: preferably the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.5 (ref. 48), supplemented by definitions used by the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group, Ponte di Legno Severe Toxicity Working Group and World Health Organization. In both Delphi rounds, participants were asked to review the draft definitions. Definitions for the core outcomes were revised based on their feedback and presented in the final feedback round by e-mail.

Step 3: future implementation

The project group selected measurement instruments for each of the core outcomes, aiming to stay as close as possible to the endorsed Delphi definitions. Draft metrics were discussed and refined during three online project group meetings until full consensus was reached on final measurement instruments ready for implementation. For the physical core outcomes, two separate sets were created. One describes survey questions for symptomatic outcomes, that is, outcomes that have already resulted in a clinical diagnosis. The other set contains asymptomatic outcomes, that is, abnormalities on surveillance or diagnostic tests with or without a clinical diagnosis, using recommended surveillance strategies from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group long-term follow-up guidelines10. For the psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes, internationally validated questionnaires were identified by expert consultation and mapped to the core outcomes. The objective was to determine the optimal coverage of these psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes and alignment with other guidelines26,27, with minimal burden of completion on the parent (proxy), patient or survivor.

Results

Step 1: preparation

A total of 555 outcomes were reported in the healthcare provider survey and 107 outcomes in the survivor focus groups. After combining these outcomes in the main groups and avoiding duplication, we included 65 unique outcomes in the candidate outcome lists for 17 separate childhood cancer types (34–47 outcomes per specific childhood cancer type) (Table 1).

Step 2: outcome selection

Response rates for the first round of the 17 surveys ranged from 70 to 97%, with a total of 435 surveys completed; response rates for the second round were between 65 and 92%, with a total of 368 surveys completed (Supplementary Table 4). Institutional approval for the Delphi surveys was waived by the Princess Máxima Center and St Jude. Participants represented 68 institutions and 19 countries (Supplementary Table 5). Based on the selection criteria, a total of 53 outcomes were carried forward from the first to the second Delphi round, with 15–28 outcomes included in each of the 17 surveys, and physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive items represented across all childhood cancer types (Table 1). Eight outcome definitions were revised and definitions were developed for three newly added outcomes.

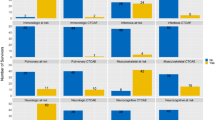

After the second Delphi round, a total of 24 unique outcomes were selected across all types of childhood cancer, in addition to overall survival and cause-specific mortality (Fig. 2 and Table 2). This translates to 7–11 outcomes per childhood cancer type.

Level A agreement was found in 21 of the 24 outcomes (Supplementary Table 6), with three level B or C outcomes included based on expert opinion (that is, stroke and temperature dysregulation in craniopharyngioma, and reduced joint mobility in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma). Three domains of quality of life were prioritized: physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive aspects. These resulted from a recategorization of all psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes and four physical outcomes (chronic pain, reduced levels of physical activity, sleep problems and fatigue) after the second Delphi round. Three outcome definitions were modified. The core sets, including definitions, were accepted in the e-mail round (Table 3).

Step 3: future implementation

Measurement instruments were selected for each of the 24 physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive core outcomes (Table 4). For the symptomatic physical core outcomes, 29 healthcare provider survey questions were formulated that capture each of the outcomes according to their Delphi definition, while allowing for outcomes to resolve using follow-up questions regarding year of diagnosis, current situation (active versus inactive) and year resolved, if applicable. For the asymptomatic physical core outcomes, an overview was created of surveillance tests recommended by the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group that have added value to capture outcomes in an early or asymptomatic stage10. These tests can be extracted from medical records, if available.

Regarding the psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes, we recommend self-report by the 23-item Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Generic questionnaire for all patients and survivors, with addition of the PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale with 18 items for those with a hematological malignancy or central nervous system tumor to capture general fatigue, cognitive fatigue and sleep or rest fatigue30,31. Most psychosocial and neurocognitive items were captured by this approach, except for three: behavioral problems, independence or autonomy and body image. Finally, for survival, we recommend performing a linkage with population registries to record overall survival and to review the medical record for the specific cause of death, depending on the available data sources in a country.

Discussion

The International Childhood Cancer Outcome Project resulted in 17 core sets of 7–11 items per childhood cancer type, amounting to a total of 24 physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes for childhood cancer. We were able to define this set of important outcomes by an extensive two-round Delphi process, including an international expert panel and survivors of childhood cancer. The core set can be used to evaluate the balance between survival and quality of survival for patients and survivors to measure progress within an organization, but also to benchmark with other institutions and identify best practices.

Strengths of this project include building on previous efforts within pediatric oncology24,25,26,27, expanding the scope to most types of childhood cancer and focusing on measures relevant to patients’ and survivors’ performance of activities in daily life. Moreover, the Delphi methodology allows equal contribution of all stakeholder types to the decision-making process, with substantial agreement in the prioritized outcomes32. Another strength is that survivors were represented in the project group and consulted in the focus groups to ensure the final core sets reflect outcomes of importance to patients and survivors33,34.

In this project, we prioritized clinically relevant outcomes for children diagnosed with or having survived cancer, harmonized outcome definitions and formulated measurement instruments. A next step will be to implement this core outcome indicator set in clinical practice. Measuring and evaluating these outcomes will be a powerful tool to advance quality of care. By focusing not just on survival but also on the outcomes most valued by patients, survivors and their healthcare providers, the delicate balance between surviving and living with the consequences of cancer and its treatment becomes visible and actionable. It allows institutions to measure the impact of their treatment strategies in terms of improved survival, reduced adverse health outcomes or a combination of the two, thereby pinpointing current care needs and opportunities for future innovations. In addition, institutions adopting the same core set may participate in benchmarking initiatives to identify best practices across healthcare organizations to further improve the quality of care.

Importantly, the occurrence of early and late adverse health outcomes is not only dependent on the quality of care but also relies on case-mix variables that describe differences between hospital populations, such as cancer subtype and stage, sex, age, genetic susceptibility, comorbidities and other demographic or clinical traits. Therefore, such data should be documented precisely and accounted for when benchmarking with other institutions35. Moreover, the outcomes should preferably be measured prospectively to improve reliability and completeness compared to retrospective evaluation.

The International Childhood Cancer Core Outcome Set most likely cannot be immediately and completely extracted from common electronic health records. However, the outcomes can be measured by medical record abstraction, concise questionnaires and linkage with existing registries. To facilitate and harmonize its implementation, we developed an overview of suggested measurement instruments. Regarding psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes, we recommend using the established PedsQL Generic and Fatigue modules for survivors of 2–18 years of age. This decision aimed to balance the instrument’s coverage of core outcomes, availability in different languages, validation across age ranges and response burden. The PedsQL is considered a legacy instrument that is used widely in childhood cancer care and research, permitting comparisons with historical data, and is free to use for clinical work. Some institutions use this measure for follow-up until age 30 years, allowing for longitudinal assessments since diagnosis, including during the transition from acute to short- and long-term follow-up care. Although the PedsQL measures health-related quality of life on a more general level, it does not capture specific conditions, such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress or suicidal ideation, in detail. However, these types of psychopathology are less common in survivors of childhood cancer36,37,38,39. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) tools represent a favorable alternative because they permit computerized adaptive testing, feature a relatively easy-to-interpret scoring system and include item banks that are increasingly becoming the international standard40,41,42. However, because PROMIS measures are currently unavailable in many languages and only adopted by a few pediatric oncology centers worldwide, we recommend using the PedsQL as the primary measure to evaluate psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes in this project. Evidently, more focused evaluations of specific physical, psychosocial or neurocognitive sequelae, preferably according to evidence-based clinical guidelines, remain important for those at higher risk of developing adverse effects10,43.

The core set should be interpreted while acknowledging that an outcome prioritized on the aggregated level might not seem relevant for the individual or, alternatively, highly relevant outcomes on the individual level might not be part of the core set. Nevertheless, a concise set of relevant outcomes provides benefits in terms of feasibility44,45,46. Furthermore, the 17 types of childhood cancer represented do not include all types of childhood cancer. This resulted partly from the relevance for the participating centers (for example, retinoblastoma is not treated at the Princess Máxima Center) or the infrequency of certain childhood cancer types (for example, thyroid carcinoma). Lastly, the candidate outcome lists that served as the starting point of the prioritization process were based on outcome collection efforts in the Netherlands. This might have induced sampling bias and limited generalizability. However, this risk is limited due to the possibility to put forth new outcomes during the Delphi process.

The successful development of the International Childhood Cancer Core Outcome Set is only the starting point of the implementation of outcome-based evaluation of quality of care. Apart from the involvement of survivor representatives and diverse healthcare providers throughout the project, additional elements, including leadership, engagement, a high-quality database, balance between patient- and provider-report and frequent communication of results are also crucial facilitators for the adoption of these core sets in clinical practice and the subsequent initiation of quality improvement efforts44,46,47.

Data availability

Most of the data have been included in the Supplementary Information to promote transparency. Additional data collected for the study, including deidentified participant data, a data dictionary defining each field in the set and the detailed summaries of each Delphi round, will be made available to others upon reasonable request until 2035. The data can be requested through the corresponding or senior authors (R.J.v.K., R.L.M. or L.C.M.K.) and will only be shared with a signed data access agreement.

Change history

13 December 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02753-2

14 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02651-7

References

Schulpen, M. et al. Significant improvement in survival of advanced stage childhood and young adolescent cancer in the Netherlands since the 1990s. Eur. J. Cancer 157, 81–93 (2021).

Gatta, G. et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5–a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 15, 35–47 (2014).

Ward, E., DeSantis, C., Robbins, A., Kohler, B. & Jemal, A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 64, 83–103 (2014).

Loeffen, E. A. H. et al. The importance of evidence-based supportive care practice guidelines in childhood cancer-a plea for their development and implementation. Support Care Cancer 25, 1121–1125 (2017).

Geenen, M. M. et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297, 2705–2715 (2007).

Bhakta, N. et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet 390, 2569–2582. (2017).

Frederiksen, L. E. et al. Surviving childhood cancer: a systematic review of studies on risk and determinants of adverse socioeconomic outcomes. Int. J. Cancer 144, 1796–1823. (2019).

Suh, E. et al. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: a retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 421–435. (2020).

van Gorp, M. et al. Increased health-related quality of life impairments of male and female survivors of childhood cancer: DCCSS LATER 2 psycho-oncology study. Cancer 128, 1074–1084. (2022).

Kremer, L. C. et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 60, 543–549 (2013).

Annett, R. D., Patel, S. K. & Phipps, S. Monitoring and assessment of neuropsychological outcomes as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 62, S460–S513 (2015).

Porter, M. E. What is value in health care? N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2477–2481 (2010).

Porter, M. E., Larsson, S. & Lee, T. H. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 504–506 (2016).

Greenzang, K. A. et al. Parental considerations regarding cure and late effects for children with cancer. Pediatrics 145, e20193552 (2020).

Morgans, A. K. et al. Development of a standardized set of patient-centered outcomes for advanced prostate cancer: an international effort for a unified approach. Eur. Urol. 68, 891–898 (2015).

Martin, N. E. et al. Defining a standard set of patient-centered outcomes for men with localized prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 67, 460–467 (2015).

Mak, K. S. et al. Defining a standard set of patient-centred outcomes for lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 48, 852–860 (2016).

Ong, W. L. et al. A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for breast cancer: the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) initiative. JAMA Oncol. 3, 677–685 (2017).

Zerillo, J. A. et al. An international collaborative standardizing a comprehensive patient-centered outcomes measurement set for colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 3, 686–694 (2017).

Cherkaoui, Z. et al. A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for pancreatic carcinoma: an international Delphi survey. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 1069–1078. (2021).

de Rooij, B. H. et al. Development of an updated, standardized, patient-centered outcome set for lung cancer. Lung Cancer 173, 5–13 (2022).

de Ligt, K. M. et al. International development of a patient-centered core outcome set for assessing health-related quality of life in metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 198, 265–281 (2023).

Alguren, B. et al. Development of an international standard set of patient-centred outcome measures for overall paediatric health: a consensus process. Arch. Dis. Child 106, 868–76. (2021).

Schmiegelow, K. et al. Consensus definitions of 14 severe acute toxic effects for childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia treatment: a Delphi consensus. Lancet Oncol. 17, e231–e239. (2016).

Andres-Jensen, L. et al. Severe toxicity free survival: physician-derived definitions of unacceptable long-term toxicities following acute lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet Haematol. 8, e513–e523. (2021).

Limond, J. et al. Quality of survival assessment in European childhood brain tumour trials, for children below the age of 5 years. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 25, 59–67 (2020).

Limond, J. A. et al. Quality of survival assessment in European childhood brain tumour trials, for children aged 5 years and over. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 19, 202–210 (2015).

Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent and young adult cancers. Version 5.0. Children’s Oncology Group http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf (2019).

van Kalsbeek, R. J. et al. European PanCareFollowUp Recommendations for surveillance of late effects of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 154, 316–328. (2021).

Varni, J. W., Burwinkle, T. M., Katz, E. R., Meeske, K. & Dickinson, P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 94, 2090–2106 (2002).

Varni, J. W., Seid, M. & Rode, C. A. The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 37, 126–139 (1999).

Williamson, P. R. et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 18, 280 (2017).

Freyer, D. R. et al. Lack of concordance in symptomatic adverse event reporting by children, clinicians, and caregivers: implications for cancer clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1623–1634. (2022).

Di Maio, M. et al. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann. Oncol. 33, 878–892. (2022).

Lingsma, H. F. et al. Comparing and ranking hospitals based on outcome: results from The Netherlands Stroke Survey. QJM 103, 99–108 (2010).

McDougall, J. & Tsonis, M. Quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review of the literature (2001–2008). Support Care Cancer 17, 1231–1246 (2009).

Wakefield, C. E. et al. The psychosocial impact of completing childhood cancer treatment: a systematic review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 35, 262–274 (2010).

Brinkman, T. M., Recklitis, C. J., Michel, G., Grootenhuis, M. A. & Klosky, J. L. Psychological symptoms, social outcomes, socioeconomic attainment, and health behaviors among survivors of childhood cancer: current state of the literature. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2190–2197 (2018).

Michel, G., Brinkman, T. M., Wakefield, C. E. & Grootenhuis, M. Psychological outcomes, health-related quality of life, and neurocognitive functioning in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 67, 1103–1134. (2020).

Cella, D., Gershon, R., Lai, J. S. & Choi, S. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual. Life Res. 16, 133–141 (2007).

Hinds, P. S. et al. PROMIS pediatric measures validated in a longitudinal study design in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 66, e27606 (2019).

Reeve, B. B. et al. Expanding construct validity of established and new PROMIS pediatric measures for children and adolescents receiving cancer treatment. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 67, e28160 (2020).

Jacola, L. M., Partanen, M., Lemiere, J., Hudson, M. M. & Thomas, S. Assessment and monitoring of neurocognitive function in pediatric cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 1696–1704. (2021).

Kampstra, N. A. et al. Health outcomes measurement and organizational readiness support quality improvement: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res 18, 1005 (2018).

Benning, L. et al. Balancing adaptability and standardisation: insights from 27 routinely implemented ICHOM standard sets. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1424 (2022).

Lansdaal, D., van Nassau, F., van der Steen, M., Bruijne, M. & Smeulers, M. Lessons learned on the experienced facilitators and barriers of implementing a tailored VBHC model in a Dutch university hospital from a perspective of physicians and nurses. BMJ Open 12, e051764 (2022).

Menard, J. C. et al. Feasibility and acceptability of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system measures in children and adolescents in active cancer treatment and survivorship. Cancer Nurs. 37, 66–74 (2014).

US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0; https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf (US DHHS, NIH, NCI, 2017).

Lee, S. J. Classification systems for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 129, 30–37 (2017).

Gudrunardottir, T. et al. Consensus paper on post-operative pediatric cerebellar mutism syndrome: the Iceland Delphi results. Childs Nerv. Syst. 32, 1195–1203 (2016).

Kilsdonk, E. et al. Late mortality in childhood cancer survivors according to pediatric cancer diagnosis and treatment era in the Dutch LATER Cohort. Cancer Invest. 40, 413–424. (2022).

Evers, J. Kwalitatief Interviewen: Kunst én Kunde 2nd edn (Boom Lemma Uitgevers, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the survivors that participated in the focus groups to share their experiences with life after childhood cancer. We also thank W. Plieger for her valuable contribution to the preparation, conduct and interpretation of the focus groups.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

R.J.v.K. and R.L.M. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, supervision, visualization, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. L.C.M.K. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. W.J.W.K., R.P., M.M.H. and M.A.G. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. D.A.M., D.M.G. and M.E. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. M.P. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. J.H., J.d.H. and A.N. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. H.M.v.S., A.Y.N.S.-v.M., H.v.T., H.M.C., L.M.J. and R.T.W. contributed to methodology, writing of the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. L.C.V. contributed to investigation. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Paul Nathan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–6.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

van Kalsbeek, R.J., Hudson, M.M., Mulder, R.L. et al. A joint international consensus statement for measuring quality of survival for patients with childhood cancer. Nat Med 29, 1340–1348 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02339-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02339-y