Abstract

Triacsins are an intriguing class of specialized metabolites possessing a conserved N-hydroxytriazene moiety not found in any other known natural products. Triacsins are notable as potent acyl-CoA synthetase inhibitors in lipid metabolism, yet their biosynthesis has remained elusive. Through extensive mutagenesis and biochemical studies, we here report all enzymes required to construct and install the N-hydroxytriazene pharmacophore of triacsins. Two distinct ATP-dependent enzymes were revealed to catalyze the two consecutive N–N bond formation reactions, including a glycine-utilizing, hydrazine-forming enzyme (Tri28) and a nitrite-utilizing, N-nitrosating enzyme (Tri17). This study paves the way for future mechanistic interrogation and biocatalytic application of enzymes for N–N bond formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

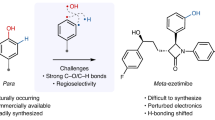

The triacsins (1–4) are a unique class of natural products containing an 11-carbon alkyl chain and a terminal N-hydroxytriazene moiety (Fig. 1). Originally discovered from Streptomyces aureofaciens as vasodilators through an antibiotic screening program1, the triacsins are most notable for their use as acyl-CoA synthetase inhibitors by mimicking fatty acids in the study of lipid metabolism2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Recently, triacsin C also showed promise in the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2-replication, where morphological effects were observed at viral replication centers11. Despite potent activities, the triacsin biosynthetic pathway, particularly the enzymatic machinery to install the N-hydroxytriazene pharmacophore, has remained obscure.

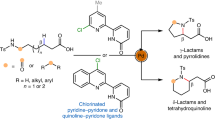

a, Schematic of the triacsin biosynthetic gene cluster in S. aureofaciens ATCC 31442. b, The proposed biosynthetic pathway of triacsins based on this work. Tri28 and Tri17 (highlighted in green) are the two ATP-utilizing enzymes that catalyze the formation of the two different N–N bonds found in triacsins.

The N-hydroxytriazene moiety, containing three consecutive nitrogen atoms, is rare in nature and has been identified only in the triacsin family of natural products12. In contrast to the prevalence of N–N linkages in synthetic drug libraries, the enzymes for N–N bond formation have only recently begun to be revealed13,14. Examples include a heme enzyme (KtzT) in kutzneride biosynthesis15, a fusion protein (Spb40) consisting of a cupin and a methionyl-transfer RNA synthetase (metRS)-like domain in s56-p1 biosynthesis16, an N-nitrosating metalloenzyme (SznF) in streptozotocin biosynthesis17, a transmembrane protein (AzpL) in 6‐diazo‐5‐oxo‐l‐norleucine formation18 and an ATP-dependent, diazo-forming enzyme (CreM) in cremeomycin biosynthesis19 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Investigation of the biosynthesis of triacsins containing two consecutive N–N bonds may determine whether known mechanisms are used or if yet new enzymes for N–N bond formation exist.

To shed light on triacsin biosynthesis, we identified the triacsin biosynthetic gene cluster (tri1-32) in S. aureofaciens through genome mining and mutagenesis studies20. Based on bioinformatic analyses and labeled precursor feeding experiments, we further proposed a chemical logic for N-hydroxytriazene biosynthesis via a key intermediate, hydrazinoacetic acid (HAA), as well as through nitrite-dependent N–N bond formation20. In the present study we scrutinized the activity of 15 enzymes for triacsin biosynthesis through biochemical analyses. We revealed all enzymes required to construct and install the unusual N-hydroxytriazene pharmacophore, highlighting a new ATP-dependent, nitrite-utilizing, N-nitrosating enzyme.

Results

N-hydroxytriazene assembly starts before PKS extension

Although we inferred from bioinformatic analysis that the acyl portion of the triacsin scaffold is derived from discrete polyketide synthases (PKSs), it was unclear with respect to the reaction timing of how nitrite and HAA pathways are coordinated with the purported acyl intermediate to form the triacsin scaffold with the N-hydroxytriazene moiety20. One hypothesis is that HAA, once loaded onto an acyl carrier protein (ACP), is modified by nitrite to form an ACP-bound intermediate that resembles the final N-hydroxytriazene moiety that is further elongated by PKSs. Alternatively, the N-hydroxytriazene moiety may serve as a PKS chain terminator rather than a ‘starter unit’. The overall odd number of carbon chain length was also puzzling, which was probably due to a decarboxylation event on the PKS chain since the carboxylate carbon of glycine, a predicted precursor of HAA, was retained (Extended Data Fig. 1a). While mutants with each of the 25 tri genes individually disrupted did not accumulate any biosynthetic intermediates or shunt products, the Δtri9-10 mutant strain, in which the two genes encoding a decarboxylase and its accessory enzyme were both deleted, abolished the production of triacsins and accumulated a new metabolite (5) (Fig. 2a). Metabolite 5 exhibited a distinct ultraviolet (UV) profile and was predicted to have the molecular formula C12H13N3O3 based on high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 1). From a 12-l fermentation culture of Δtri9-10, 2.5 mg of 5 was obtained as a yellow and amorphous powder. Subsequent one- and two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis revealed 5 to be a new triacsin-like metabolite with a 12-carbon unsaturated alkyl chain terminated by a carboxylic acid moiety (Supplementary Note 1). Metabolite 5 was unstable, and >90% had degraded after 2 days at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). The presence of both the N-hydroxytriazene moiety and the terminal carboxylic acid in 5 argued against the possibility of the N-hydroxytriazene moiety as a PKS chain terminator. We thus propose that the N-hydroxytriazene assembly starts before PKS extension (Fig. 1).

a, HPLC/UV trace (360 nm) demonstrating accumulation of a new metabolite (5) in the Δtri9-10 mutant and abolition of triacsin production. b, Biochemical analysis of Tri109. Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) showing that Tri10 purified from E. coli converted 5 to 6 only when coexpressed with Tri9 (Tri109). Calculated masses for 5 (m/z = 248.1030 ([M + H]+) and 6 (m/z = 204.1132 ([M + H]+) were used for each trace with a 10-ppm mass error tolerance. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

To confirm that 5 was a direct substrate for Tri10, a UbiD-family nonoxidative decarboxylase (Tri10) was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified for biochemical analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, Tri9 is homologous to UbiX, a flavin prenyltransferase that modifies FMN using an isoprenyl unit to generate prFMN, a required cofactor for the activity of UbiD21,22,23,24. As expected, the purified Tri10 alone showed no activity toward 5 presumably due to the absence of the required cofactor (Fig. 2b). By contrast, the purified Tri10 that was coexpressed with Tri9 in E. coli successfully decarboxylated 5 based on HRMS analysis with the concomitant production of CO2 (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 1b). While the full structural characterization of the decarboxylated product of 5 was not feasible due to instability of both substrate and product, the UV profile and HRMS data of the reaction product were consistent with decarboxylated product 6 (Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition, 6 was also identified as a minor metabolite from the culture broth of wild-type S. aureofaciens (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Considering that only 5 was accumulated in Δtri9-10, we proposed that 6 was probably a precursor for all observed triacsin congeners varying in the unsaturation pattern of their alkyl chains (Fig. 1).

Succinylation is required for HAA activation

We previously proposed that HAA, presumably generated through the activities of Tri26-28, is a key intermediate for triacsin biosynthesis20. Specifically, N6-hydroxy-lysine (7), which is generated by Tri26 (an N-hydroxylase homolog), reacts with glycine, promoted by Tri28 (a cupin and metRS didomain protein), to form N6-(carboxymethylamino)lysine (8), which then undergoes oxidative cleavage to yield HAA and 2-aminoadipate 6-semialdehyde catalyzed by Tri27, an FAD-dependent, d-amino acid oxidase homolog. The Tri26-28 coupled biochemical assay successfully produced HAA by comparison to an authentic standard through 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB) derivatization16,25, confirming the predicted activity of Tri26-28 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, Tri26 was found to hydroxylate lysine but not ornithine, and the coupled assay with Tri26/28 generated 8 as expected, further confirming the activity of each enzyme (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b).

a, EICs demonstrating production of a derivatized HAA from coupled Tri26-28 assays subjected to DNFB derivatization. Omission of any enzyme or glycine resulted in abolition of HAA-DNP. The calculated mass for HAA-DNP (m/z = 257.0517 ([M + H]+) was used for each trace. b, EICs showing production of 8 from coupled Tri26-28 assays. The cupin and metRS domains were individually dissected and tested in parallel. The calculated mass for 8 (m/z = 220.1292 ([M + H]+) was used for each trace. c, EICs showing production of various acyl-HAA products generated by Tri31. Individual masses used for each trace are listed. d, EICs showing production of 10 (+12 charge) along with its deconvoluted mass and Ppant fragment. Omission of Tri29 or 9 (generated in situ using Tri31) resulted in abolition of 10. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

We next dissected Tri28 to obtain insight into the roles of the cupin and metRS domains in forming the N–N bond between 7 and glycine. Each domain was individually purified from E. coli, and recombination of each domain in the in vitro assay showed successful, albeit less efficient, formation of 8 than the intact didomain enzyme, demonstrating the feasibility of domain dissection (Fig. 3a,b). The production of 8 required the activity of both domains of Tri28, as shown in the coupled assays used to produce HAA (Fig. 3a). The assay with the Tri28_metRS domain alone generated a putative ester intermediate or a spontaneously rearranged product26 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5c), suggesting that the cupin domain of Tri28 promoted the intramolecular rearrangement of the ester intermediate to form 8. Tri28 was revealed to have a single zinc coordination site for each domain by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy (ICP–OES) analyses, consistent with its homolog PyrN (40% sequence similarity) (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e)27.

After confirming the production of HAA, we next probed the fate of HAA in the N-hydroxytriazene assembly. Tri26-28 is part of a putative six-gene operon of tri26-31 that is homologous to spb38-43 in s56-p1 biosynthesis16, whereas the functions of tri29-31, putatively encoding an AMP-dependent synthetase, an ACP and an N-acetyltransferase, respectively, remained unknown for both triacsin and s56-p1 biosynthesis. We hypothesized that Tri29 activates HAA through adenylation and then loads it onto Tri30. Tri31 possibly acetylates the distal nitrogen of the purported hydrazine moiety as a protecting group, similar to the activity of FzmQ/KinN28,29. A biochemical assay with Tri29 and the holo-ACP, Tri30, yielded no HAA-S-Tri30 based on liquid chromatography (LC)–HRMS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that Tri31 previously acetylates HAA to the Tri29-catalyzed activation and loading onto ACP. A subsequent assay of Tri31 with HAA and acetyl-CoA, however, did not yield acetyl-HAA (Fig. 3c). Instead, a new product of mass consistent with succinyl-HAA (9) was detected in a trace amount (Supplementary Fig. 7). We hypothesized that 9 was generated from succinyl-CoA, which tightly bound to the Tri31 protein purified from E. coli. LC–HRMS analysis of the purified Tri31 protein solution revealed a trace amount of succinyl-CoA as compared to the standard, and the addition of extra succinyl-CoA to the Tri31 assay increased the yield of 9, consistent with our hypothesis (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 7).

The preference of Tri31 for succinyl-CoA over acetyl-CoA was unexpected based on the prediction of Tri31 as an N-acetyltransferase. To exclude the possibility of an artifact due to copurification of succinyl-CoA with Tri31, we next investigated the acyl-CoA substrate specificity of Tri31 using various CoA substrates. Tri31 recognized all tested acyl-CoAs except acetyl-CoA, and moderately preferred succinyl-CoA over others based on kinetic analysis (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 8). The promiscuity of Tri31 also made it possible to confirm that Tri31 acylates the distal nitrogen of HAA, because purification of products such as hexanoyl-HAA is more feasible from in vitro assays than 9 due to its increased hydrophobicity. The NMR analysis of hexanoyl-HAA showed a 3J 1H-15N HMBC cross-peak between the nitrogen-bearing methylene (δH 3.69) and the amide nitrogen (δN 144.7), as well as a 2J 1H-15N HMBC cross-peak between the amide -NH- (δH 9.68) and the other nitrogen (δN 61.7), supporting the notion that the distal nitrogen of HAA is connected to the carbonyl carbon of the CoA substrate (Supplementary Note 2).

The activation and loading of all acyl-HAAs generated by Tri31 were then tested using a coupled assay containing Tri29-31. The succinyl-HAA-loaded Tri30 (10) was successfully generated based on both the intact protein HRMS and phosphopantetheine (Ppant) ejection assay (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, none of the other acyl-HAAs were loaded onto Tri30 (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating that Tri29 acts as a gatekeeper enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway and succinylation is required for HAA activation and loading onto ACP (Fig. 1).

Hydrazone starter unit for PKS extension

Tri22, an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase homolog, was proposed to oxidize 10 as the next step in N-hydroxytriazene formation. Tri22 was recombinantly expressed in E. coli as a yellow protein containing flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) (Supplementary Fig. 10a,b). An in vitro assay of Tri22 with 10 generated in situ by Tri29-31 resulted in its conversion to a product with mass consistent with 11 and reduction of FAD to FADH2 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 10c). To confirm the proposed structure of 11, the reaction product was subjected to base hydrolysis to release the free acid that was further derivatized by ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPTA) for LC–UV–HRMS analysis30,31. The expected acid product, 2-hydrazineylideneacetic acid (2-HYAA), was also chemically synthesized and derivatized by OPTA. By comparison, the structure of 11 was confirmed to be 2-HYAA attached to Tri30 (Extended Data Fig. 3, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11). It is notable that a time-course experiment with Tri22 showed no detectable reaction intermediates due to the sole activity of dehydrogenation or hydrolysis of Tri22 (Supplementary Fig. 10d). Tri22 showed no activity toward free acid 9 (Supplementary Fig. 11), demonstrating the necessity of a carrier protein for Tri22 recognition.

a, Biochemical analysis of Tri22. EICs demonstrating production of 11 (+12 charge) along with its deconvoluted mass and Ppant fragment. Omission of Tri22 resulted in abolition of 11. Metabolite 10 was generated in situ using Tri29-31. b, Hydrazone translocation catalyzed by Tri13. EICs showing production of 12 (+6 charge) along with its deconvoluted mass and Ppant fragment. Omission of Tri20 or Tri13 resulted in abolition of 12. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Metabolite 11 was proposed to be the first possible substrate to react with the presumed nitrite for N-hydroxytriazene formation during triacsin biosynthesis. We then biochemically reconstituted the activity of Tri16 (a lyase) and Tri21 (a flavin-dependent enzyme)—the CreD and CreE homolog32, respectively—to confirm that nitrous acid can be generated by the pathway enzymes. After confirming the production of nitrite by Tri16/21 (Supplementary Fig. 12), we began to search for a nitrite-utilizing enzyme that modifies 11 to form N-hydroxytriazene. There was weak evidence that an acyl-CoA ligase homolog, CreM, promoted the reaction of an aryl amine with nitrite to form diazo in cremeomycin biosynthesis19, although CreM seemed not to be required for diazo formation32. The triacsin biosynthetic gene cluster encodes a CreM homolog, Tri17 (40% sequence similarity), which is essential for triacsin biosynthesis based on a mutagenesis study20. However, an in vitro assay of Tri17 with nitrite, ATP and 11 yielded no new product. Notably, AMP was formed in the presence of nitrite and Tri17, suggesting that Tri17 may activate nitrite using ATP (Supplementary Fig. 13a).

Although enzyme(s) other than Tri17 were probably responsible for the third nitrogen addition, we reasoned that 11 might not be a correct substrate and that the N-hydroxytriazene formation might take place at a later stage, after PKS extension and release of the polyketide intermediate. While the discrete nature and lack of some essential enzymes (probably shared with fatty acid biosynthesis in the native producer) made the in vitro reconstitution of the entire PKS machinery a formidable task, the biochemical assay containing Tri13, a ketosynthase homolog (KAS III) that is related to certain KSs catalyzing transacylation33,34, and Tri20, a free-standing ACP, demonstrated that Tri13 promoted translocation of the 2-HYAA moiety from Tri30 to Tri20 to yield 12 (Fig. 4b). This observation suggested that the PKS extension probably takes place on Tri20 with a hydrazone starter unit. After five rounds of extension to yield 13, the 12-carbon fully unsaturated alkyl chain would be released as a carboxylic acid to produce 14 (Fig. 1). Tri14, a peptidase homolog, may play a thioesterase role in facilitating this hydrolytic release of the polyketide product. To probe the activity of Tri14, we purified a soluble version of Tri14 from E. coli following cleavage of its predicted N-terminal recognition sequence for self-activation35. Due to the unavailability of 13, surrogate substrates such as hexanoyl-S-Tri20 and lauroyl-S-Tri20 were generated using Sfp, a promiscuous Ppant transferase36, and used in the Tri14 assays (Supplementary Fig. 14). Tri14 exhibited a hydrolytic activity toward lauroyl-S-Tri20 but not toward hexanoyl-S-Tri20, demonstrating an acyl chain length preference (Extended Data Fig. 4). In addition, Tri14 showed no activity toward lauroyl-S-Tri30, consistent with the hypothesis that PKS extension occurs on Tri20 rather than Tri30 (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 14). These results strongly suggested that Tri14 is a plausible enzyme to catalyze the hydrolytic release of 14 from 13 (Fig. 1).

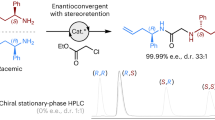

Tri17 completes N-hydroxytriazene assembly following PKS

Structural comparison of 14 and 5 suggested that the third nitrogen addition could occur on 14 following the PKS assembly line. Considering that 14 was probably more unstable than 5, as suggested by the literature37, we turned to a surrogate substrate, 15, to probe the activity of Tri17 (Fig. 5a). Metabolite 15 was chemically synthesized (Supplementary Note 4) and used in the Tri17 assay, together with ATP and nitrite. A new product was successfully produced, which was identified as triacsin A (1) by comparison with the authentic standard isolated from the wild-type culture of S. aureofaciens (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 15a and Supplementary Note 5). This product was not observed in negative controls, where each individual component such as Tri17, ATP, nitrite or 15 was omitted (Fig. 5a). The utilization of 15N-nitrite also led to the expected mass spectral shift of the product (Fig. 5a), further confirming the utilization of nitrite by Tri17 in N–N bond formation. We further determined the kinetic parameters (catalytic constant (kcat) and Michaelis constant (KM)) of Tri17 towards 15 (kcat = 40.6 ± 6.4 min−1, KM = 301 ± 53 µM), nitrite (kcat = 0.49 ± 0.05 min−1, KM = 18.5 ± 4.3 µM) and ATP (kcat = 0.39 ± 0.03 min−1, KM = 64.2 ± 6.7 µM) (Supplementary Fig. 15b). The production of AMP was slightly increased in the presence of 15, and pyrophosphate was suggested to be produced by Tri17, consistent with the proposed reaction mechanism of Tri17 in which 15 nucleophilically attacks the ATP-activated nitrite to yield 1 with the release of AMP (Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 13b).

a, EICs showing the production of 1 from assays containing Tri17, ATP, nitrite and 15. Omission of any one of these components led to the abolition of 1. Utilization of 15N-nitrite resulted in the expected mass spectral shift. b, EICs demonstrating the production of 1 from a coupled Tri16/21/17 assay containing aspartate, 15, NADPH and ATP. Omission of any one of these components led to the abolition of 1. Utilization of 15N-aspartate resulted in the expected mass spectral shift. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

We next probed whether nitrous acid, generated enzymatically by Tri16/21, could be utilized by Tri17. A biochemical assay containing Tri16, Tri21 and Tri17 with aspartic acid, NADPH, ATP and 15 resulted in the production of 1, and the utilization of 15N-aspartic acid led to the expected mass spectral shift of 1 (Fig. 5b), confirming the utilization of nitrite generated by Tri16/21 in N-hydroxytriazene biosynthesis. Notably, no spontaneous formation of 1 was observed using either nitrite or enzymatically generated nitrite in the absence of Tri17 (Fig. 5a,b). We thus deduced that, in triacsin biosynthesis, Tri17 takes nitrite and 14 as substrates and catalyzes the production of 5 in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Tri17 appeared to be promiscuous toward acyl chain modifications, because both 14 and 15 could be recognized. However, neither 2-HYAA nor 12-aminododecanoic acid was recognized by Tri17 based on comparative metabolomics analysis (Supplementary Fig. 16), suggesting the activity of Tri17 is both chain length and hydrazone specific. Notably, Tri17 did not utilize nitrate to modify 15 (Supplementary Fig. 16), indicating that Tri17 is a dedicated nitrite-utilizing N-nitrosating enzyme.

Discussion

Our extensive bioinformatics, mutagenesis and biochemical analysis allowed proposal of the complex biosynthetic pathway for triacsins, particularly the N-hydroxytriazene moiety unique to this class of natural products (Fig. 1). Biosynthesis starts with the production of HAA from lysine and glycine catalyzed by Tri26-28, which is then succinylated by a succinyltransferase, Tri31, and activated and loaded onto Tri30 promoted by an acyl-ACP ligase, Tri29. Tri22, an acyl-ACP dehydrogenase, catalyzes desuccinylation and oxidation of HAA to a hydrazone moiety attached to Tri30, which is then translocated to another free-standing ACP, Tri20, facilitated by a ketosynthase, Tri13, for PKS extension. The PKS machinery probably includes ketosynthases encoded by tri6-7, a ketoreductase encoded by tri5, two dehydratases encoded by tri11-12 and a malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase that is shared with the host fatty acid synthase machinery. Tri6/7 probably form heterodimers in which Tri6 performs the canonical Claisen-like decarboxylative condensation, while Tri7, lacking an active site cysteine, acts as a chain length factor that controls the number of iterative elongation steps38,39,40,41,42,43. Tri11/12 also probably dimerize to form a functional dehydratase44,45. After five iterations of ketosynthase, reductase and dehydratase, a fully unsaturated polyketide chain is hydrolytically released from Tri20 promoted by a thioesterase, Tri14. Tri17, an ATP-dependent N-nitrosating enzyme, recognizes this highly unstable biosynthetic intermediate, 14, and catalyzes the formation of 5 to finish N-hydroxytriazene assembly using nitrite generated by Tri16/21. Metabolite 5 subsequently undergoes nonoxidative decarboxylation promoted by Tri9/10 and various reduction/oxidation reactions—probably catalyzed by Tri18/19, two remaining oxidoreductases encoded by the gene cluster—to yield triacsin congeners varying in the unsaturation pattern of their alkyl chains (Fig. 1). We propose that N-nitrosation occurs before decarboxylation in the pathway since 5, but not 14, was detected from the Δtri9-10 mutant. However, we could not rule out the possibility that decarboxylation might precede N-nitrosylation. This proposed biosynthetic pathway was consistent with failure to detect intermediate accumulation in most of the gene deletion mutants because most of the presumed biosynthetic intermediates were either attached to an ACP or highly unstable.

The biosynthesis of triacsins features two distinct mechanisms for the two consecutive N–N bond formations. One involves Tri28, a cupin and metRS didomain protein, which catalyzes the formation of N6-(carboxymethylamino)lysine (8) from N6-hydroxy-lysine (7) and glycine. Previous work established a proposed reaction scheme for Spb40, a homolog of Tri28 (75% sequence similarity), using filtered culture broth from E. coli expressing the recombinant Spb40 and isotope-labeled substrates16. However, the utilization of whole-cell lysate rather than purified enzymes precluded detailed biochemical characterization of this enzyme, leaving unanswered questions such as the tRNA requirement and true functions of each of two domains. Using purified Tri28 and the dissected individual domains, we revealed that tRNA was not required for the activity of Tri28. Glycine is thus most probably activated by ATP to form glycyl-AMP, which is subjected to nucleophilic attack by 7 to form an ester intermediate, presumably catalyzed by the metRS domain (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5c). The cupin domain was demonstrated to be essential for the formation of 8, presumably by promoting the rearrangement of the ester intermediate in N–N bond formation. The cupin domain has been implicated in a wide array of enzymatic activities and is usually metal binding46,47. Bioinformatic analysis of the cupin domain of Tri28 showed that it probably contains a 3-His-1-Glu metal-binding site. This site is most commonly associated with iron, but there is also a precedent for the coordination of zinc, nickel and copper46,47. We revealed that Tri28_cupin bound zinc rather than the more common iron for catalysis (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e). The critical role of zinc was supported by previous mutagenesis results where E. coli producing the Spb40 mutant with the substitution of alanine for His45, one of the key residues for metal binding of the cupin domain that is also conserved in Tri28, abolished the ability to produce 8 (ref. 16). Although PyrN, a homolog of Tri28 involved in pyrazomycin biosynthesis, was recently found to catalyze a similar reaction to Tri28 with two equivalents of zinc bound, biochemical insight was precluded due to lack of in vitro activity27. Further biochemical and structural analysis will provide more insights into the catalytic mechanism of this intriguing family of enzymes.

This study also identified a new N-nitrosating enzyme, Tri17, which catalyzes N-hydroxytriazene formation from nitrite and acyl hydrazone in an ATP-dependent way. Tri17 is homologous to an acyl-CoA ligase but CoA is not a required substrate, suggesting that an AMP derivative is a plausible biosynthetic intermediate (Extended Data Fig. 5). Although nitrite has been implicated to react with an amine for N–N bond formation in multiple natural product biosynthesis, such as cremeomycin19,32, fosfazinomycin29, kinamycin28, alanosine48,49 and alazopeptin18, the underlying enzymology often remains elusive, lacking a definitive biochemical characterization using purified enzymes. For example, CreM, a homolog of Tri17, was previously reported to catalyze diazotization in cremeomycin biosynthesis, although the evidence was weak because of its low solubility in E. coli and the high reactivity of nitrite to nonenzymatically react with an aryl amine to form a diazo moiety19,29. Similarly, nonenzymatic N-nitrosation using nitrite could occur in alanosine and fragin biosynthesis49,50, although other possibilities such as a fusion protein (AlnA) consisting of a cupin and an AraC‐like DNA‐binding domain, or a CreM homolog encoded elsewhere on the genome, were also proposed to be an N−N-bond-forming enzyme, but without evidence48,49. AzpL, a transmembrane protein with no homology to any characterized protein, was recently revealed to catalyze diazotization in alazopeptin biosynthesis through mutagenesis and heterologous expression, but no in vitro biochemical evidence was obtained due to the nature of the membrane protein18. Other enzyme candidates that may catalyze N−N bond formation using nitrite were also proposed in fosfazinomycin and kinamycin biosynthesis (FzmP and KinJ, respectively), but these hypothetical proteins have not been studied28,29. The discovery of Tri17 provided a solid example of a nitrite-utilizing enzyme required for N–N bond formation, and provides the basis for future mechanistic understanding of this new family of dedicated N-nitrosating enzymes.

In conclusion, through identification of a highly unstable biosynthetic intermediate from mutagenesis studies and biochemical analysis of 15 enzymes required for triacsin biosynthesis, we have revealed the exquisite timing and mechanisms of the biosynthesis of this intriguing class of natural products. Two distinct ATP-dependent enzymes have been revealed to catalyze the two consecutive N–N bond formations of N-hydroxytriazene, including a glycine-utilizing, hydrazine-forming enzyme and a nitrite-utilizing, N-nitrosating enzyme. This study paves the way for the future discovery, mechanistic understanding and biocatalytic application of enzymes for N–N bond formation.

Methods

Materials

Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (NEB) was used for PCR reactions. Restriction enzymes were purchased from Thermo Scientific. All chemicals used in this work were obtained from Alfa Aesar, Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific, unless otherwise noted. CoA substrates (purity >95%) were obtained from CoALA Biosciences. Hydrazinoacetic acid HCl salt (purity 95%) was purchased from BOC Sciences. 15N-aspartic acid (purity 98%) and 15N-sodium nitrite (purity >98%) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The wild-type and Δtri9-10 gene disruption mutant of Streptomyces aureofaciens ATCC 31442 were cultured on ISP4 agar plates to allow sporulation. Individual spore colonies were inoculated into a 2-ml seed culture of R5 liquid medium and grown at 30 °C and 240 rpm for 48 h. The seed culture was inoculated into 30 ml of R5 liquid medium and grown for 5 days at 30 °C and 240 rpm before cell harvesting. Culturing was performed in 125-ml Erlenmeyer vessels with a wire coil placed at the bottom to encourage aeration. Large-scale culturing of wild-type S. aureofaciens was conducted as previously reported20. For large-scale culturing of the Δtri9-10 mutant, the 2-ml seed culture would instead be inoculated in 1 l of R5 liquid medium and grown under the same conditions. Escherichia coli strains were cultivated either on lysogeny broth (LB) agar plates or in LB liquid medium. Growth media were supplied with antibiotics as required at the following concentrations: kanamycin (50 μg ml–1), apramycin (50 μg ml–1) and ampicillin (100 μg ml–1).

LC–HRMS analysis of triacsins and 5

Streptomycete cultures were pelleted by centrifugation (4,000g for 15 min), and spent media were extracted 1:1 by volume with ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate was removed by rotary evaporation, and the dry extract was dissolved in 300 μl of methanol for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis by 10-μl injection onto an Agilent Technologies 6120 Quadrupole LC–MS instrument with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). For LC–HRMS analysis, the extract in methanol could be diluted by a factor of five for LC–HRMS and HRMS/MS analysis by 10-μl injection onto an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS instrument with the same column. Linear gradients of 5–95% acetonitrile (v/v) in water with 0.1% formic acid (v/v) at 0.5 ml min–1 were used.

Production and purification of 5 and 1

After the 5-day culture period for the Δtri9-10 mutant of S. aureofaciens, cultures were pelleted by centrifugation (4,000g for 15 min), and spent medium was extracted 1:1 by volume with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate was removed by rotary evaporation and the dry extract was dissolved in a 1:1 mixture (v/v) of dichloromethane and methanol. The dissolved extract was loaded onto a size exclusion column packed with Sephadex LH-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and manually fractionated in a 1:1 dichloromethane and methanol running solvent. The fractions were screened by LC–MS with a diode array detector. Fractions containing the compound determined to be 5 were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an Agilent 1260 HPLC and an Atlantis T3 OBD Prep column (100 Å pore size, 5 μm particle size, 10 × 150 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase buffered to a pH of 7.2 with ammonium bicarbonate was used to prevent exposure of the fractions to acidic conditions. Linear gradients of 5–50% acetonitrile (v/v) at 2.5 ml min–1 were used for initial purification. Final purification of 5 was performed using an isocratic gradient at 14% acetonitrile using the same mobile phase, column and flow rate. All fractions containing the product were kept covered to avoid light exposure, and stored under N2 gas whenever practically achievable to avoid chemical degradation. Purified products were dried and analyzed by LC–MS and NMR. All NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE at 900 MHz (1H NMR) and 226 MHz (13C NMR). NMR spectra were analyzed using Mestrenova 9.0.1. LC–HRMS, and gas chromatography–MS (GC–MS) data for the entire work were analyzed using Agilent Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis 10.0. The production and purification procedure of 1 was conducted as previously reported20.

Labeled precursor feeding of 1-13C-glycine

Streptomyces aureofaciens was cultured as described in Bacterial strains and growth conditions. Twenty-four hours after the 30-ml inoculation, the culture was supplied with 10 mM 1-13C-glycine. Compound extraction and LC–HRMS analysis were performed as described above.

Construction of plasmids for expression in E. coli

Three vectors were used for E. coli-induced expression of recombinant proteins with polyhistidine tags. The plasmid pETDuet-1 was used for the dual expression of Tri10 and Tri9 (Tri109). The tri10 gene was amplified with HindIII and NotI sites and inserted into the first multiple cloning site (MCS) of pETDuet-1 which encodes an N-terminal polyhistidine tag. The tri9 gene was amplified using NdeI and XhoI sites and inserted into the second MCS of pETDuet-1 that encodes a C-terminal S-tag derived from pancreatic ribonuclease A. The plasmid pET-24b(+) was used for the expression of Tri28, Tri28_Cupin, Tri28_metRS, Tri30, Tri20, Tri17, Tri13 and Tri14 with C-terminal polyhistidine tags. The NdeI and XhoI sites were used for the restriction digest and ligation-based installation of the corresponding gene. The plasmid pLATE52 was used for the expression of Tri16, Tri21, Tri26, Tri27, Tri22, Tri29 and Tri31 with N-terminal polyhistidine tags. The corresponding genes were amplified and inserted through ligation-independent cloning following the protocol from Thermo Fisher Scientific’s aLICator Expression System (no. K1281). All genes were amplified from either S. aurofaciens ATCC 31442 or S. tsukubaensis NRRL 18488, as listed in Supplementary Table 2. Oligonucleotides utilized in this study were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and all strains and constructs are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

The expression and purification for all proteins used in this study followed the same general procedure for polyhistidine tag purification as detailed here. Expression strains were grown at 37 °C in 1 l of LB in a shake flask supplemented with 50 µg ml–1 kanamycin or 100 µg ml–1 of ampicillin to an OD600 of 0.5 at 250 rpm. The shake flask was then placed over ice for 10 min and induced with 120 μM of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The cells were then incubated for 16 h at 16 °C and 250 rpm to undergo protein expression. Subsequently, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,371g, 15 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was removed. The cell pellet was resuspended in 30 ml of lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole) and cells were lysed by sonication on ice. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (27,216g, 1 h, 4 °C) and the supernatant was filtered with a 0.45-μm filter before batch binding. Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) was added to the filtrate at 2 ml l–1 cell culture, and the samples were allowed to nutate for 1 h at 4 °C. The protein/resin mixture was loaded onto a gravity flow column. Flowthrough was discarded and the column was then washed with approximately 25 ml of wash buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) and tagged protein was eluted in approximately 20 ml of elution buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). The entire process was monitored using a Bradford assay. Purified proteins were concentrated and exchanged into exchange buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) using Amicon ultra filtration units. After two rounds of buffer exchange and concentration, the purified enzyme was removed and glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10% (v/v). Enzymes were subsequently flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C or used immediately for in vitro assays. The presence and purity of purified enzymes was assessed using SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and the concentration was determined using a NanoDrop UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Tri13 and Tri14 were purified using the same general procedure outlined in the previous section, with the following changes. After washing the column with wash buffer, proteins were eluted out with 5 ml of elution buffer containing 50, 100, 150 and 250 mM imidazole, respectively. Fractions containing the desired protein were pooled together after analysis with SDS–PAGE.

Tri22 was purified with the procedure outlined here. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C. The pellet was then resuspended in lysis buffer (buffer A) containing Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol and 20 mM imidazole. The slurry was lysed by sonication for 20 min on an ice bath. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000g for 40 min and the resulting supernatant was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA affinity column. The loaded column was washed with a 50-column volume of lysis buffer (buffer A) and then eluted with elution buffer (buffer A) containing 200 mM imidazole. Pooled fractions containing the target protein were concentrated and exchanged with a buffer containing 20 mM NaCl using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device (30-kDa MWCO, Millipore). Filtered protein was applied to a MonoQ 4.6/100 PE (1.7 ml, Cytiva) column and eluted at a flow rate of 1.5 ml min–1. Bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–500 mM NaCl in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0. Pooled protein from the MonoQ column was further applied to the Hiload 16/60 Superdex 200pg (Cytiva) for size exclusion chromatography. The target protein was collected, concentrated to 1.8 mg ml–1 and flash-frozen for subsequent assays.

All proteins reported in this study were purified using the HEPES pH 8.0 buffer system (unless stated otherwise), except for Tri29 for which Tris pH 7.5 was used to avoid precipitation following concentration. Purification buffers for Tri30 and Tri20 (ACPs) contained 1 mM TCEP. BL21 Star (DE3) was utilized for expression of all proteins. In the case of Tri30 and Tri20, BAP1 was utilized to obtain the holo-ACPs, and BL21 Star (DE3) was utilized for purification of apo-ACPs.

The approximate molecular mass and yield for each protein were as follows: Tri26 (52.4 kDa, 5.2 mg l–1), Tri27 (40.9 kDa, 5.4 mg l–1), Tri28 (74.7 kDa, 18.5 mg l–1), Tri28-metRS (62.3 kDa, 6.8 mg l–1), Tri28-cupin (14.1 kDa, 22.7 mg l–1), Tri29 (57.5 kDa, 34.3 mg l–1), Tri30 (11 kDa, 16.9 mg l–1), Tri20 (9.8 kDa, 10.8 mg l–1), Tri13 (34.5 kDa, 4.3 mg l–1), Tri31 (25.1 kDa, 20.5 mg l–1), Tri22 (45.9 kDa, 0.5 mg l–1), Tri21 (71.8 kDa, 6.4 mg l–1), Tri16 (59.6 kDa, 15.2 mg l–1), Tri17 (61.5 kDa, 34 mg l–1), Tri109 (56.7 kDa, 4.6 mg l–1) and Tri14 (27.7 kDa, 2.1 mg l–1).

LC–HRMS and GC–MS analysis of Tri109 in vitro reconstitution

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 μl of 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 20 μM Tri10 and 100 μM 5. Compound 5 was delivered in the form of partially purified extracts from the tri9-10 gene disruption mutant, hydrated in water with 0.5% methanol (v/v) to aid solubility. The concentration of 5 in the extracts was estimated by HPLC/UV analysis at 400 nm. The final methanol concentration in the reaction volume was 0.1% (v/v). Following the 30-min incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 2 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed on an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). Using a water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, analysis was performed with a linear gradient of 5–95% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

The GC–MS procedure used to detect CO2 was adapted from previous work51. GC–MS assays consisted of 4.5 ml of reaction mixture containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 1 mM 5 and 100 μM Tri109. The reaction was performed in a 10-ml sealed headspace vial (Agilent) and initiated by addition of the substrate. One milliliter of the headspace gas was acquired using a gastight syringe (Hamilton) and injected into an Agilent 5977A GC–MS system equipped with a HP-5ms column. Injector temperature was set at 120 °C, and helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 3 ml min–1. The temperature gradient was 40–100 °C for 5 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in electron ionization mode with automatically tuned parameters, and the acquired mass range was m/z = 15–100. The CO2 signal was confirmed using an authentic standard and by extracting m/z = 44.

LC–HRMS analysis of Tri26 and Tri28 in vitro reconstitution

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 1 mM lysine, 1 mM glycine, 2 mM NADPH, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM Tri26 and 20 μM Tri28. After the 30-min incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed on an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent InfinityLab Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A mobile phase of water/acetonitrile was buffered with 10 mM ammonium formate and titrated to a pH of 3.2 with formic acid. LC–HRMS analysis was performed with a decreasing linear gradient of 90–60% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min–1. Analogous assays were performed using the individual domains of Tri28. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

LC–HRMS analysis of HAA production by Tri26-28 with DNFB derivatization

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM lysine, 1 mM glycine, 2 mM NADPH, 0.2 mM FAD, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM Tri26, 20 μM Tri27 and 20 μM Tri28 (the same concentration was used for dissected domains). The DNFB derivatization method was adapted from a previous work25. The reaction was then derivatized with 200 μl of 1 mM DNFB dissolved in 200 mM borate pH 9.0 and incubated for 30 min at 60 °C. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. The same derivatization method was utilized with an authentic HAA standard. At least two independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

ICP–OES analysis of Tri28

Tri28, Tri28_metRS and Tri28_cupin were further purified using a Hiload 16/60 Superdex 200pg (Cytiva) for size exclusion chromatography (0.5 ml min–1). FPLC-purified proteins were then exchanged through spin-filtration with Chelex-treated buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) to reduce enzyme-independent metal contamination. Proteins were subsequently lyophilized and resuspended in 70% trace-metal-grade nitric acid. Desiccated proteins were boiled in acid-washed Pyrex glass containers. The samples were then resuspended in 2% trace-metal-grade nitric acid to the following concentrations: Tri28 (8.97 µM for multi-metal screen, 1.74 µM for zinc quantification with individual domains), Tri28_cupin (1.22 µM) and Tri28_metRS (1.28 µM). A Chelex-treated buffer sample with the same volume was treated in the same manner as controls. Metal standards were prepared using a 2% trace-metal-grade nitric acid matrix. The concentration of trace elements was determined using a Perkin Elmer 5300 DV ICP–OES at the College of Natural Resources, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

LC–HRMS analysis of Tri31 in vitro reconstitution

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 μl of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0 containing 1 mM succinyl-CoA, 2 mM HAA and 50 μM Tri31. After the 30-min incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 5–95% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. The same methodology was performed using different CoA substrates. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Identification of copurified succinyl-CoA in Tri31

Fifty microliters of 1.7 mM Tri31 was quenched with 100 μl of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed on an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent InfinityLab Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A mobile phase of water/acetonitrile was buffered with 10 mM ammonium formate and titrated to a pH of 3.2 with formic acid. LC–HRMS analysis was performed with a decreasing linear gradient of 90–60% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min–1. An authentic succinyl-CoA standard was utilized to compare the retention time and mass spectrum to the succinyl-CoA copurified from Tri31.

Determination of kinetic parameters for CoA substrates from Tri31 reaction

The procedure to obtain kcat/KM parameters for CoA substrates was adopted from previous work18,30. Reactions were performed at room temperature in 100 μl of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 50 μM CoA substrate, 2 mM HAA, 0.1 mM 5,5’-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and 20 μM Tri31. For each CoA substrate, a control reaction without enzyme was conducted. Activity was monitored continually over a 15-min period by measuring the increase in absorbance at 412 nm using a SpectraMax M2 plate reader from the reaction between the free thiol of CoASH and DNTB. Initial velocities were approximated using the extinction coefficient 14,150 M−1 cm−1 and subtracting the control reactions from each substrate to correct for background activity. Each CoA substrate was tested in independent triplicate assays.

Large-scale Tri31 biochemical assay with HAA and hexanoyl-CoA

A 1-ml reaction was performed at room temperature for 15 h containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 5 mM HAA, 4 mM hexanoyl-CoA and 100 μM Tri31. The reaction was extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The organic fraction was dried over nitrogen and analyzed using NMR. Supplementary Note 2 contains further structural characterization.

LC–HRMS analysis of Tri30 loading reaction and Ppant ejection assays with HAA and CoA substrates

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 20 min in 50 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 0.2 mM succinyl-CoA, 1 mM HAA, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM Tri31, 20 μM Tri29 and 50 μM Tri30. After the 20-min incubation period, the reaction was diluted with four volumes of purified water and chilled on ice to slow further reaction progress. The diluted reaction mixture was immediately filtered by a 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) filter, and 15 μl was promptly injected onto an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with a Phenomenex Aeris 3.6-μm Widepore XB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm2). Using a water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, analysis was performed with a linear gradient of 30–50% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min–1. The molecular masses of proteins observed during electrospray ionization were determined using ESIprot to deconvolute the array of observed charge state spikes52. For Ppant ejection assays, the same conditions were used but the source voltage was increased from 75 to 250 V to increase fragmentation of the phosphodiester bond covalently linking the Ppant prosthetic to a holo-ACP. The same methodology was performed using different CoA substrates. To determine whether HAA could be directly loaded (without Tri31 and succinyl-CoA), the same methodology was used with the following changes: a linear gradient of 40–60% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min–1 and the Phenomenex Aeris 3.6-μm Widepore XB-C18 column (2.1 × 250 mm2) were utilized. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

LC–HRMS analysis of Tri22 activity on 10

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 20 min in 50 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 0.2 mM succinyl-CoA, 1 mM HAA, 5 mM ATP, 0.2 mM FAD, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM Tri31, 20 μM Tri29, 20 μM Tri22 and 50 μM Tri30. After the 20-min incubation period, the reaction was diluted with four volumes of purified water and chilled on ice to slow further reaction progress. For the time-course experiment, reactions were incubated for 5 , 15 , 30 and 60 min either using or omitting FAD. The diluted reaction mixture was immediately filtered by a 0.45-μm PVDF filter, and 15 μl was promptly injected and analyzed using the methodology described in the previous section. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Identification of FAD Tri22 cofactor

Purified Tri22 (yellow color) was boiled for 10 min and precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min). The supernatant was further analyzed using LC–UV–MS with an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. The UV spectrum was monitored at 420 nm and the mass spectrum/retention time was compared to an authentic FAD standard.

Detection of reduced FADH2 cofactor

The Tri22 activity assay described above was performed at room temperature for 20 min alongside an assay lacking HAA. The UV spectrum for both samples was monitored at 300–500 nm using a SpectraMax M2 plate reader.

Determination of 11 from Tri22 reaction

The biochemical assay consisting of HAA, succinyl-CoA, HAA, Tri29-31 and Tri22 was performed as described above, except that 50 μM of each enzyme was utilized and the assay was performed at the 100-μl scale. After the 20-min incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was isolated by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was discarded. The protein pellet was then dissolved in 100 μl of 100 mM KOH for 10 min at room temperature, followed by neutralization with 100 μl of 100 mM HCl. The solution was spin-filtered using a 2-kDa Amicon spin filter to remove protein residues and isolate the flowthrough, which was subjected to OPTA derivatization30. The derivatization agent was prepared by mixing 1 ml of 80 mM OPTA with 98 mM of 2-ME (both dissolved in 200 mM NaOH). One hundred microliters of flowthrough was combined with 100 μl of the derivatization agent. The reaction mixture was vortexed and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 2 min. The mixture was analyzed using LC–UV–MS with an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. 2-HYAA was chemically synthesized and subjected to the same derivatization procedure with OPTA. The mass spectrum, retention time and UV from the biochemical assays were compared to that of the standard. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

LC–HRMS analysis of 2-HYAA translocation to Tri20 using Tri13

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 50 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM succinyl-CoA, 2 mM HAA, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM FAD, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM Tri31, 20 μM Tri29, 20 μM Tri22, 30 μM Tri30, 20 μM Tri20 and 10 μM Tri13. After the incubation period, the reaction was diluted with four volumes of purified water and chilled on ice to slow further reaction progress. The diluted reaction mixture was immediately filtered by a 0.45-μm PVDF filter and 15 μl was promptly injected and analyzed using the methodology described above, with the exception that a Phenomenex Aeris 3.6-μm Widepore XB-C18 column (2.1 × 250 mm2) was used. At least two independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Lauroyl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA loading assays on Tri30 and Tri20 using Sfp

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 50 μl of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 2.5 mM CoA substrate, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 μM ACP and 50 μM Sfp. After the 30-min incubation period, the reaction was diluted with four volumes of purified water and chilled on ice to slow further reaction progress. The diluted reaction mixture was immediately filtered by a 0.45-μm PVDF filter, and 10 μl was promptly injected onto an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with a Phenomenex Aeris 3.6-μm Widepore XB-C18 column (2.1 × 250 mm2) and a Phenomenex Aeris 3.6-μm Widepore XB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm2) for lauroyl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA assay, respectively. Using a water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, analysis was performed with a linear gradient of 30–98 and 30–50% acetonitrile for lauroyl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA assay, respectively, at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min–1. The analyses used to deconvolute protein spikes and obtain the Ppant fragment are analogous to those described above. Hexanoyl-CoA and lauroyl-CoA were loaded to Tri20, while only lauroyl-CoA was loaded to Tri30. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Tri14 hydrolysis activity assays on fatty acyl-ACP substrates

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 1 h in 100 μl of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 2.5 mM CoA substrate, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 μM ACP, 50 μM Tri14 and 50 μM Sfp. After the 1-h incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. Hexanoic and lauric acid standards were prepared and analyzed to test the hydrolytic activity of Tri14. Assays with hexanoyl-CoA and lauroyl-CoA were utilized with Tri20, while lauroyl-CoA was utilized solely for Tri30. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Griess test for nitrite production by Tri21 and Tri16

Reactions were performed at room temperature in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 0.1 mM FAD, 1 mM NADPH or NADH, 1 mM aspartate, 20 μM Tri21 and 20 μM Tri16. The reaction was prepared with all reagents except NAD(P)H and aliquoted identically into 12 wells. Reactions were initiated simultaneously by the addition of NAD(P)H with a multichannel pipette. Starting with an initial time point, one reaction well was quenched every 4 min by the addition of one volume of Griess reagent (Cell Signaling Technology).

Tri17 activity assay on 15

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM 15, 4 mM sodium nitrite (or 15N-sodium nitrite), 5 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM Tri17. Chemically synthesized 15 was dissolved in DMSO to ensure full solubility, and assays were maintained at a final concentration of 2% DMSO (v/v). After the incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. Compound 1 isolated from wild-type S. aureofaciens was utilized as a standard to compare retention time, mass spectrum and UV profiles between biochemical assays. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown. Analogous assays were performed with nitrate rather than nitrite, and 2-HYAA or 12-aminododecanoic acid rather than 15, respectively.

Coupled Tri16, Tri21 and Tri17 activity assay

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 1 h in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.1 mM FAD, 1 mM NADPH, 1 mM aspartate (or 2 mM 15N-aspartate), 20 μM Tri16 and 20 μM Tri21. After the incubation period, 100 μl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.5 mM 15, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM Tri17 were added to the first reaction. The coupled assay was incubated at room temperature for 16 h. After the incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. Compound 1 isolated from wild-type S. aureofaciens was utilized as a standard to compare retention time, mass spectrum and UV profiles between biochemical assays. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Comparative metabolomics

Tri17 assays utilizing nitrate, 2-HYAA or 12-aminododecanoic acid were analyzed via LC–HRMS using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. Peak picking and comparative metabolomics were performed using MSDial (v.4.38), with peak lists exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 365 Student).

AMP detection from Tri17 assay

Reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min, as described above. After the incubation period, the reaction was quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. A similar assay was performed using 11 (generated enzymatically as described above) as a substrate rather than 15. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed on an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent InfinityLab Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A mobile phase of 90% acetonitrile and water was buffered with 10 mM ammonium acetate and titrated to a pH of 9.0 with ammonium hydroxide. LC–HRMS analysis was performed with a decreasing linear gradient of 81–43% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min–1. ATP, ADP and AMP were also detected by monitoring of UV at 260 nm.

Determination of Tri17 kinetic parameters toward 15

Assays were performed in triplicate in 50 µl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 5 mM nitrite, 5 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2 and 20 µM Tri17. The tested concentrations for 15 were: 50 µM, 250 µM, 500 µM, 1 mM and 2 mM. The incubation times for the reactions were 1, 5, 10, 20 and 40 min, which were used to determine the initial velocity of the reaction. After each incubation period, the reactions were quenched with two volumes of chilled methanol. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (15,000g, 5 min) and the supernatant was used for analysis. LC–HRMS analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6545 Q-TOF LC–MS equipped with an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm2). A water/acetonitrile mobile phase with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and a linear gradient of 2–98% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min–1 was utilized. Product concentration was estimated by comparison to authentic standard 1. Kinetic parameters were determined and plotted using GraphPad Prism.

Determination of Tri17 kinetic parameters toward nitrite

Assays were performed in triplicate in 50 µl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 2 mM 15, 5 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2 and 20 µM Tri17. The tested concentrations for nitrite were: 10 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM, 500 µM and 1 mM. Inorganic pyrophosphate released from these enzymatic assays was measured continuously using the EnzChek Pyrophosphate Assay Kit (ThermoFisher). The 20X buffer, MESG substrate, purine nucleoside phosphorylase and inorganic pyrophosphatase were added following the manufacturers’ protocols. Reactions were initiated by the addition of nitrite and monitored at 360 nm using a SpectraMax M2 plate reader. Initial velocities were calculated using the standard curve for inorganic pyrophosphate. Kinetic parameters were determined and plotted using GraphPad Prism.

Determination of Tri17 kinetic parameters toward ATP

Assays were performed in triplicate in 50 µl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 containing 2 mM 15, 5 mM nitrite, 4 mM MgCl2 and 20 µM Tri17. The tested concentrations for ATP were: 10 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM, 500 µM and 1 mM. The inorganic pyrophosphate released from these enzymatic assays was measured continuously using the EnzChek Pyrophosphate Assay Kit (ThermoFisher). The 20X buffer, MESG substrate, purine nucleoside phosphorylase and inorganic pyrophosphatase were added following the manufacturers’ protocols. Reactions were initiated by the addition of nitrite and monitored at 360 nm using a SpectraMax M2 plate reader. Initial velocities were calculated using the standard curve for inorganic pyrophosphate. Kinetic parameters were determined and plotted using GraphPad Prism.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, Supplementary information and the Extended data, and/or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tanaka, H., Yoshida, K., Itoh, Y. & Imanaka, H. Structure and synthesis of a new hypotensive vasodilator. Tetrahedron Lett. 22, 1809–1812 (1981).

Hartman, E. J., Omura, S., Laposata, M. & Triacsin, C. A differential inhibitor of arachidonoyl-CoA synthetase and nonspecific long chain acyl-CoA synthetase. Prostaglandins 37, 62–73 (1989).

Omura, S., Tomoda, H., Xu, M. Q., Takahashi, Y. & Iwai, Y. T. Triacsins, new inhibitors of acyl-CoA synthetase produced by Streptomyces sp. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 39, 1211–1218 (1986).

Hiroshi, T., Kazuaki, I. & Satoshi, O. Inhibition of acyl-CoA synthetase by triacsins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 921, 595–598 (1987).

Tomoda, H., Igarashi, K., Cyong, J. C. & Omura, S. Evidence for an essential role of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase in animal cell proliferation: inhibition of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase by triacsins caused inhibition of Raji cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 4214–4219 (1991).

Kim, J. H., Lewin, T. M. & Coleman, R. A. Expression and characterization of recombinant rat acyl-CoA synthetases 1, 4, and 5: selective inhibition by triacsin C and thiazolidinediones. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24667–24673 (2001).

Matsuda, D., Namatame, I., Ohshiro, T., Ishibashi, S. & Tomoda, H. J. Anti-atherosclerotic activity of triacsin C, an acyl-CoA synthetase inhibitor. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 61, 318–321 (2008).

Nakayama, T. et al. Enhanced lipid metabolism induces the sensitivity of dormant cancer cells to 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy. Sci. Rep. 11, 7290 (2021).

Guo, F. et al. Amelioration of cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro and in vivo by targeting parasite fatty acyl-coenzyme a synthetases. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1279–1287 (2014).

Ernst, A. M. et al. S-palmitoylation sorts membrane cargo for anterograde transport in the Golgi. Dev. Cell 47, 479–493 (2018).

Silvas, J. A. et al. Inhibitors of VPS34 and lipid metabolism suppress SARS-CoV-2 replication. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.18.210211v1 (2020).

Blair, L. M. & Sperry, J. Natural products containing a nitrogen-nitrogen bond. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 794–812 (2013).

Le Goff, G. & Ouazzani, J. Natural hydrazine-containing compounds: biosynthesis, isolation, biological activities and synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 6529–6544 (2014).

Waldman, A. J., Ng, T. L., Wang, P. & Balskus, E. P. Heteroatom-heteroatom bond formation in natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 117, 5784–5863 (2017).

Du, Y. L., He, H. Y., Higgins, M. A. & Ryan, K. S. A heme-dependent enzyme forms the nitrogen-nitrogen bond in piperazate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 836–838 (2017).

Matsuda, K. et al. Discovery of unprecedented hydrazine-forming machinery in bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9083–9086 (2018).

Ng, T. L., Rohac, R., Mitchell, A. J., Boal, A. K. & Balskus, E. P. An N-nitrosating metalloenzyme constructs the pharmacophore of streptozotocin. Nature 566, 94–99 (2019).

Kawai, S. et al. Complete biosynthetic pathway of alazopeptin, a tripeptide con‐sisting of two molecules of 6‐diazo‐5‐oxo‐L-norleucine and one molecule of alanine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 10319–10325 (2021).

Waldman, A. J. & Balskus, E. P. Discovery of a diazo-forming enzyme in cremeomycin biosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 83, 7539–7546 (2018).

Twigg, F. F. et al. Identifying the biosynthetic gene cluster for triacsins with an N-hydroxytriazene moiety. ChemBioChem 20, 1145–1149 (2019).

White, M. D. et al. UbiX is a flavin prenyltransferase required for bacterial ubiquinone biosynthesis. Nature 522, 502–506 (2015).

Payne, K. A. P. et al. New cofactor supports α,β-unsaturated acid decarboxylation via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Nature 522, 497–501 (2015).

Tian, G. & Liu, Y. Mechanistic insights into the catalytic reaction of ferulic acid decarboxylase from Aspergillus niger: a QM/MM study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 7733–7742 (2017).

Marshall, S. A., Payne, K. A. P. & Leys, D. The UbiX-UbiD system: the biosynthesis and use of prenylated flavin (prFMN). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 632, 209–221 (2017).

Hegedus, H., Gergely, A., Veress, T. & Horváth, P. Novel derivatization with Sanger’s reagent (2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene [DNFB]) and related methodological developments for improved detection of amphetamine enantiomers by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Analusis 27, 458–463 (1999).

Garg, R. P., Qian, X. L., Alemany, L. B., Moran, S. & Parry, R. J. Investigations of valanimycin biosynthesis: elucidation of the role of seryl-tRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6543–6547 (2008).

Zhao, G. et al. The biosynthetic gene cluster of pyrazomycin—a C-nucleoside antibiotic with a rare pyrazole moiety. ChemBioChem 21, 644–649 (2020).

Wang, K. K. A. et al. Glutamic acid is a carrier for hydrazine during the biosyntheses of fosfazinomycin and kinamycin. Nat. Commun. 9, 3687 (2018).

Huang, Z., Wang, K. K. A. & Van Der Donk, W. A. New insights into the biosynthesis of fosfazinomycin. Chem. Sci. 7, 5219–5223 (2016).

Zhang, W., Bolla, M. L., Kahne, D. & Walsh, C. T. A three enzyme pathway for 2-amino-3-hydroxycyclopent-2-enone formation and incorporation in natural product biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6402–6411 (2010).

Jones, B. N. & Gilligan, J. P. O-phthaldialdehyde precolumn derivatization and reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of polypeptide hydrolysates and physiological fluids. J. Chromatogr. A 266, 471–482 (1983).

Sugai, Y., Katsuyama, Y. & Ohnishi, Y. A nitrous acid biosynthetic pathway for diazo group formation in bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 73–75 (2016).

Nofiani, R., Philmus, B., Nindita, Y. & Mahmud, T. 3-Ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS) III homologues and their roles in natural product biosynthesis. MedChemComm 10, 1517–1530 (2019).

Masschelein, J. et al. A dual transacylation mechanism for polyketide synthase chain release in enacyloxin antibiotic biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. 11, 906–912 (2019).

Saridakis, V. et al. Crystal structure of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum conserved protein MTH1020 reveals an NTN-hydrolase fold. Proteins 48, 141–143 (2002).

Quadri, L. E. N. et al. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carder protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37, 1585–1595 (1998).

Yoshida, K. et al. Studies on new vasodilators, WS-1228 A and B I. Discovery, taxonomy, isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) XXXV, 157–163 (1981).

Hertweck, C., Luzhetskyy, A., Rebets, Y. & Bechthold, A. Type II polyketide synthases: gaining a deeper insight into enzymatic teamwork. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 162–190 (2007).

Chen, A., Re, R. N. & Burkart, M. D. Type II fatty acid and polyketide synthases: deciphering protein-protein and protein-substrate interactions. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35, 1029–1045 (2018).

Szu, P. H. et al. Analysis of the ketosynthase-chain length factor heterodimer from the fredericamycin polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 18, 1021–1031 (2011).

Grammbitter, G. L. C. et al. An uncommon type II PKS catalyzes biosynthesis of aryl polyene Ppgments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16615–16623 (2019).

Du, D., Katsuyama, Y., Shin-ya, K. & Ohnishi, Y. Reconstitution of a type II polyketide synthase that catalyzes polyene formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 1954–1957 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Reconstitution of a highly reducing type II PKS system reveals 6π-electrocyclization is required for O-dialkylbenzene biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2962–2969 (2021).

Sacco, E. et al. The missing piece of the type II fatty acid synthase system from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14628–14633 (2007).

Rui, Z. et al. Biochemical and genetic insights into asukamycin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24915–24924 (2010).

Dunwell, J. M., Purvis, A. & Khuri, S. Cupins: the most functionally diverse protein superfamily? Phytochemistry 65, 7–17 (2004).

Stipanuk, M. H., Simmons, C. R., Karplus, P. A. & Dominy, J. E. Thiol dioxygenases: unique families of cupin proteins. Amino Acids 41, 91–102 (2011).

Ng, T. L. et al. The l-alanosine gene cluster encodes a pathway for diazeniumdiolate biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 21, 1155–1160 (2020).

Wang, M., Niikura, H., He, H. Y., Daniel-Ivad, P. & Ryan, K. S. Biosynthesis of the N–N-bond-containing compound l-alanosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 3881–3885 (2020).

Jenul, C. et al. Biosynthesis of fragin is controlled by a novel quorum sensing signal. Nat. Commun. 9, 1297 (2018).

Jonnalagadda, R. et al. Biochemical and crystallographic investigations into isonitrile formation by a non-heme iron-dependent oxidase/decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100231 (2021).

Winkler, R. ESIprot: a universal tool for charge state determination and molecular weight calculation of proteins from electrospray ionization mass spectrometry data. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24, 285–294 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank T.-Y. Huang and B. McCloskey at UC Berkeley for their assistance with initial GC–MS experiments and consultation in designing experiments. We thank M. Zhang from the UC Berkeley Catalysis Center for training with the GC–MS apparatus and aiding with data interpretation, J. Pelton for helping with NMR spectroscopic analysis and W. Yang for helping with ICP–OES analysis. The GC–MS work was made possible by the Catalysis Facility of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, supported by the Director, Office of Science, of the US Department of Energy (contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231). This research was financially supported by grants to W.Z. from the NIH (nos. R01GM136758 and DP2AT009148) and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Investigator Program. We thank Z. Hu for helpful discussions regarding the complex biosynthesis of triacsins. Lastly, we thank Y. Shen for assistance in protein purification and kinetic assays.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.R.F. designed the experiments, performed all in vitro experiments with purified enzymes, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. F.F.T. designed experiments to detect the biosynthetic intermediate, constructed plasmids for protein expression in E. coli and analyzed data. Y.D. analyzed all NMR data. W.C. performed GC–MS experiments and helped analyze NMR data. D.Q.A. helped purify the biosynthetic intermediate. M.S. isolated triacsin A. M.J.D., M.N. and J.G. aided in protein purification, construction of plasmids and repeating biochemical assays for this study. N.A.Z. performed comparative metabolomics work. R.Z. performed FPLC purification for Tri22, Tri28 and individual domains. W.Z. designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Chemical Biology thanks Jonathan Caranto, Yohei Katsuyama and Jurgen Rohr for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The decarboxylation event in triacsin biosynthesis.

a) Feeding of unlabeled and labeled glycine to the triacsin producing cultures. HRMS analysis of 3 from a S. aureofaciens culture provided with 10 mM 1-13C-glycine demonstrated that the carboxylate carbon of glycine was retained in triacsin C (3). b) Detection of CO2 production from the Tri109 biochemical assay. GC-MS chromatograms extracted with m/z = 44, demonstrating CO2 production from a Tri109 assay containing 5 as compared with an authentic standard. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least two independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 2 In vitro reconstitution of Tri26 and Tri28.

a) EICs showing the production of 7 in an assay containing Tri26, lysine, and NADPH. Tri26 selectively hydroxylates lysine and not ornithine. The calculated mass for 7: m/z = 163.1078 ([M + H]+) is used for each trace, except for the ornithine assay in which the calculated mass for N-OH-Orn was used (m/z = 149.0921 ([M + H]+)). b) EICs demonstrating that the production of 8 is dependent on Tri28, glycine, lysine, and ATP, along with the Tri26 assay components. The calculated mass for 8: m/z = 220.1292 ([M + H]+) is used for each trace. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of the Tri22-catalyzed reaction product, 11.

a) Schematic of a biochemical assay performed containing HAA, succinyl-CoA, Tri29-31, and Tri22 that is subjected to base hydrolysis, followed by OPTA derivatization to yield 2-HYAA-D. b) EICs showing the generation of 2-HYAA-D from the biochemical assay previously described in comparison with a derivatized 2-HYAA synthesized standard. Omission of Tri22, HAA, or succinyl-CoA from the couple enzymatic reaction resulted in abolishment of 2-HYAA-D. The calculated mass for 2-HYAA-D: m/z = 265.0642 ([M + H]+) is used for each trace. A 10-ppm mass error tolerance was used for each trace. At least three independent replicates were performed for each assay, and representative results are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 4 In vitro analysis of Tri14, a putative thioesterase.