Abstract

Electrodes with low work functions are required to efficiently inject electrons into semiconductor devices. However, when the work function drops below about 4 electronvolts, the electrode suffers oxidation in air, which prevents its fabrication in ambient conditions. Here we show that multivalent anions such as oxalate, carbonate and sulfite can act as powerful latent electron donors when dispersed as small ion clusters in a matrix, while retaining their ability to be processed in solution in ambient conditions. The anions in these clusters can even n-dope the semiconductor core of π-conjugated polyelectrolytes that have low electron affinities, through a ground-state doping mechanism that is further amplified by a hole-sensitized or photosensitized mechanism in the device. A theoretical analysis of donor levels of these anions reveals that they are favourably upshifted from ionic lattices by a decrease in the Coulomb stabilization of small ion clusters, and by irreversibility effects. We attain an ultralow effective work function of 2.4 electronvolts with the polyfluorene core. We realize high-performance, solution-processed, white-light-emitting diodes and organic solar cells using polymer electron injection layers with these universal anion donors, demonstrating a general approach to chemically designed and ambient-processed Ohmic electron contacts for semiconductor devices.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within this Article and its Supplementary Information and Figure files.

References

Lüssem, B., Riede, M. & Leo, K. Doping of organic semiconductors. Phys. Status Solidi A 210, 9–43 (2013).

Wei, P., Oh, J. H., Dong, G. & Bao, Z. Use of a 1H-benzoimidazole derivative as an n-type dopant and to enable air-stable solution-processed n-channel organic thin-film transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8852–8853 (2010).

Guo, S. et al. n-doping of organic electronic materials using air-stable organometallics. Adv. Mater. 24, 699–703 (2012).

Lin, X. et al. Beating the thermodynamic limit with photo-activation of n-doping in organic semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 16, 1209–1215 (2017).

Hoven, C. V. et al. Ion motion in conjugated polyelectrolyte electron transporting layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10976–10977 (2007).

Lee, B. H. et al. Multi-charged conjugate polyelectrolytes as a versatile work function modifier for organic electronic devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 1100–1108 (2014).

Tang, C. G. et al. Doped polymer semiconductors with ultrahigh and ultralow work functions for ohmic contacts. Nature 539, 536–540 (2016).

Li, C. Z. et al. Doping of fullerenes via anion-induced electron transfer and its implication for surfactant facilitated high performance polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 25, 4425–4430 (2013).

Weber, C. D., Bradley, C. & Lonergan, M. C. Solution phase n-doping of C60 and PCBM using tetrabutylammonium fluoride. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 303–307 (2014).

Nonoguchi, Y. et al. Simple salt-coordinated n-type nanocarbon materials stable in air. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3021–3028 (2016).

Reilly, T. H. III, Hains, A. W., Chen, H. & Gregg, B. A. A self-doping, O2-stable, n-type interfacial layer for organic electronics. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 455–460 (2012).

Wu, Z. et al. n-type water/alcohol-soluble naphthalene diimide-based conjugated polymers for high-performance polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2004–2013 (2016).

Russ, B. et al. Tethered tertiary amines as solid-state n-type dopants for solution-processable organic semiconductors. Chem. Sci. 7, 1914–1919 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Self-doped, n-type perylene diimide derivatives as electron transport layers for high-efficiency polymer solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700232 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. Counterion-tunable n-type conjugated polyelectrolytes for the interface engineering of efficient polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19447 (2017).

Hu, Z. et al. Self-doped n-type water/alcohol soluble-conjugated polymers with tailored backbones and polar groups for highly efficient polymer solar cells. Sol. RRL 1, 1700055 (2017).

Guha, S., Goodson, F. S., Corson, L. J. & Saha, S. Boundaries of anion/naphthalenediimide interactions: from anion-π interactions to anion-induced charge-transfer and electron-transfer phenomena. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13679–13691 (2012).

Matsunaga, Y., Goto, K., Kubono, K., Sako, K. & Shinmyozu, T. Photoinduced color change and photomechanical effect of napthalene diimides bearing alkylamine moieties in the solid state. Chem. Eur J. 20, 7309–7316 (2014).

Bradley, C. & Lonergan, M. C. Limits on anion reduction in an ionically functionalized fullerene by cyclic voltametry with in situ conductivity and absorbance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 8777–8783 (2016).

Tan, J. K., Png, R. Q., Zhao, C. & Ho, P. K. H. Ohmic transition at contacts key to maximizing fill factor and performance of organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 3269 (2018).

Chia, P. J. et al. Injection-induced de-doping in a conducting polymer during device operation: asymmetry in the hole injection and extraction rates. Adv. Mater. 19, 4202–4207 (2007).

Nicolai, H. T. et al. Unification of trap-limited electron transport in semiconducting polymers. Nat. Mater. 11, 882–887 (2012).

Chua, L. L. et al. General observation of n-type field-effect behaviour in organic semiconductors. Nature 434, 194–199 (2005).

Abbaszadeh, D. et al. Elimination of charge carrier trapping in diluted semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 15, 628–633 (2016).

Zhou, M. et al. Effective work functions for the evaporated metal/organic semiconductor contacts from in-situ diode flatband potential measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 013501 (2012).

Campbell, I. H., Joswick, M. D. & Parker, I. D. Direct measurement of the internal electric field distribution in a multilayer organic light-emitting diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 67, 3171–3173 (1995).

Olthof, S. et al. Ultralow doping in organic semiconductors: evidence of trap filling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 176601 (2012).

Nicolai, H. T. et al. Space-charge-limited hole current in poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene) diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 172107 (2010).

Hwang, J. H., Wan, A. & Kahn, A. Energetics of metal–organic interfaces: new experiments and assessment of the field. Mater. Sci. Eng. Rep. 64, 1–31 (2009).

Zhou, M. et al. The role of δ-doped interfaces for Ohmic contacts to organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 036601 (2009).

Kotadiya, N. B. et al. Universal strategy for Ohmic hole injection into organic semiconductors with high ionization energies. Nat. Mater. 17, 329–334 (2018).

Wang, X. B., Yang, X., Nicholas, J. B. & Wang, L. S. Photodetachment of hydrated oxalate dianions in the gas phase, C2O4 2 −(H2O)n (n = 3–40): from solvated clusters to nanodroplet. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 3631–3640 (2003).

Chia, P. J. et al. Direct evidence for the role of the Madelung potential in determining the work function of doped organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 096602 (2009).

Png, R. Q. et al. Madelung and Hubbard interactions in polaron band model of doped organic semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 7, 11948 (2016).

Glasser, L. Solid-state energetics and electrostatics: Madelung constants and Madelung energies. Inorg. Chem. 51, 2420–2424 (2012).

Baker, A. D. & Baker, M. D. Madelung constants of nanoparticles and nanosurfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 14793–14797 (2009).

Zaikowski, L. et al. Polarons, bipolarons, and side-by-side polarons in reduction of oligofluorenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10852–10863 (2012).

Zamadar, M., Asaoka, S., Grills, D. C. & Miller, J. R. Giant infrared absorption bands of electrons and holes in conjugated molecules. Nat. Commun. 4, 2818 (2013).

Trefz, D. et al. Electrochemical investigations of the n-type semiconducting polymer P(NDIOD-T2) and its monomer: new insights in the reduction behavior. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 22760–22771 (2015).

Poplavskyy, D., Nelson, J. & Bradley, D. D. C. Ohmic hole injection in poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene) polymer light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 707–709 (2003).

van Woudenbergh, T. V., Wilderman, J., Blom, P. W. M., Bastiaansen, J. J. A. M. & Langeveld-Vos, B. M. W. Electron-enhanced hole injection in blue polyfluorene-based polymer light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 14, 677–683 (2004).

Broggi, J., Terme, T. & Vanelle, P. Organic electron donors as powerful single-electron transfer reducing agents in organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 384–413 (2014).

Dadashi-Silab, S., Doran, S. & Yagci, Y. Photoinduced electron transfer reactions for macromolecular synthesis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10212–10275 (2016).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Novel electron-injection layers for top-emission OLEDs. In SID Int. Symp. Digest. Tech. Papers, 35, 154 (2004).

Vaynzof, Y., Kabra, D., Chua, L. L. & Friend, R. H. Improved electron injection in poly(9,9′-dioctylfluorene)-co-benzothiodiazole via cesium carbonate by means of coannealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 113306 (2011).

Yamamoto, T., Kaiji, H. & Ohmori, Y. Improved electron injection from silver electrode for all solution-processed polymer light-emitting diodes with Cs2CO3: conjugated polyelectrolyte blended interfacial layer. Org. Electron. 15, 1077–1082 (2014).

Lin, Y. Z. et al. An electron acceptor challenging fullerenes for efficient polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 27, 1170–1174 (2015).

Belaineh, D. et al. Perfluorinated ionomer-modified hole-injection layers: ultrahigh-workfunction but non-Ohmic contacts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 5504–5511 (2015).

Onwubiko, A. et al. Fused electron deficient semiconducting polymers for air stable electron transport. Nat. Commun. 9, 416 (2018).

Seah, W. L. et al. Interface doping for ohmic organic semiconductor contacts using self-aligned polyelectrolyte counterion monolayer. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2017).

Johnson, R.D. III (ed.) NIST Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 101, Release 19 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2018); http://cccbdb.nist.gov/.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. W. Y. Teo, Y. Wang, M. C. Y. Ang and A. Y. H. Ang for contributions to the experimental work, and Sumitomo Chemical for support. This research is partially funded by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its Competitive Research Programme (CRP award no. NRF-CRP 11-2012-03: R-144-000-339-281, R-143-000-608-281).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.-Q.P. led the device heterostructure and interface work. L.-L.C. led the materials chemistry and development work. P.K.H.H. led the theory work and performed the solid-state corrections. M.N.S, Q.-M.K., J.Z. and Q.-J.S. synthesized and characterized the materials. C.G.T. performed the DFT calculations. Fabrication and characterization of the diagnostic devices was performed by C.G.T., M.N.S. and Q.-M.K.; by C.Z. for the organic solar cells; and by M.J.H. and M.J.C. for the white LEDs. J.H.B., I.G. and M.J.H. provided industry insights. All authors discussed the experiments and results. R.-Q.P., L.-L.C. and P.K.H.H. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

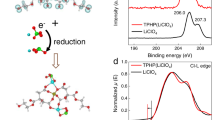

Extended Data Fig. 1 Chemical structure and ion exchange characterization.

a, Chemical structures of the materials used in this work. b, Transmission infrared spectroscopy of: top, N2(X) film before (red spectrum) and after (green) TfO− exchange with Ox2− by the contact ion-exchange protocol; and bottom, N6(Ox) film from the one-pot protocol (blue). Key vibrational modes of TfO− (magenta dashed lines) and Ox2− (green dashed lines) are marked. c, X-ray photoemission spectroscopy of the N3(X) film before (red spectrum) and after (blue) TfO− exchange with Ox2−. The N:S:C ratio for N3(TfO) is 1.95:2.0:54.0 (from measurement) and 2.0:2.0:54.0 (from theory); for N3(Ox) it is 2.0:0.03:56.0 (from measurement) and 2.0:0.0:56.0 (from theory). The large upshift in binding energy upon ion exchange is due to shift of Fermi level as a consequence of electron doping in the XPS chamber.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Atomic force microscopy of the film surfaces before and after ion exchange.

a, N3(TfO) (10-nm thick) film cast from 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5-octafluoro-1-pentanol onto a fused silica substrate cleaned with O2 plasma. b, N3(Ox) film, from a after contact ion-exchange with 80 mM Na2Ox in 4:1 v/v H2O:MeOH mixture. The nodular surface topography, characteristic of π-conjugated polyelectrolyte films deposited from moderately good solvents, is substantially unaffected by ion exchange. Root-mean-square roughness (Rrms) is 4.7 nm and 3.1 nm for N3(TfO) and N3(Ox), respectively. The image size is 3 × 3 μm and the full z scale (shown at right) is 40 nm.

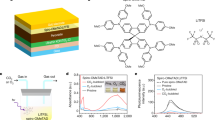

Extended Data Fig. 3 Invariance of J–V characteristics with N3(Ox) thickness.

The device structure is ITO/30 nm PEDT:PSSH/100 nm PFOP/N3(Ox)/Ag. Data from two representative diodes (solid and open symbols) are shown for each EIL thickness. The characteristics overlap, indicating a negligible voltage drop across the EIL even at a high current density of 1,000 mA cm−2. This is in contrast to the nominally undoped ‘transport’ interlayers reported in the literature, in which low conductivity limits the usable film thickness and useful current density to less than 5 nm and 100 mA cm−2, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Observation of electron and hole SCLC in PFOP diodes.

a–c, Electron-dominated devices are ITO/20 nm PEDT:PSSCsH/d nm PFOP/EIL, where the EIL is 10 nm N3(SO3)/Ag (a); 3.5 nm LiF/10 nm Ca/Al (b); and 30 nm Ba/Ag (c). d, The hole-dominated devices are ITO/20 nm mTFF-C2F5SIS/d nm PFOP/Al, where mTFF-C2F5SIS is a self-compensated, hole-doped poly(fluorene-alt-phenylene-(m-trifluoromethylphenylimino)-phenylene) with a work function of 5.75 eV. The thickness d for each PFOP layer is indicated by the colour of the symbols, and data from two representative diodes (solid and open symbols) are shown for each d. Data for the electron-dominated devices are plotted for a second sweep, high-to-low direction, at −5 V s−1. Data for the hole-dominated devices are plotted for a first sweep, high-to-low direction, at −5 V s−1. Electron SCLC behaviour is observed in a and b. Hole SCLC behaviour is observed in d, where the apparent hole mobility increases from 7 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−4 cm2 V−1 s−1 as the thickness of PFOP increases from 50 nm to 100 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Diode Vbi and subgap absorption by d.c. bias-dependent electroabsorption spectroscopy in other diodes.

a–c, In-phase electroabsorption spectra (left panels) and energy level diagram (right panels) for ITO/PEDT:PSSH/PFOP/10 nm N3(SO3)/Ag (a); ITO/PEDT:PSSH/TFB/Ca/Al (b); and ITO/PEDT:PSSH/OC1C10-PPV/10 nm N3(Ox)/Ag (c). The key for a–c is given below the plots. Vdc is applied to the ITO. The Vbi of a diode identical to c but with Ca/Al in place of N3(Ox)/Ag is 1.95 V, which gives the effective work function of OC1C10-PPV/Ca to be 3.0 eV. All semiconductor layers were 100-nm thick; feature and parameter explanations are as given in Fig. 2.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Hess cycle for computation of the solid-state adiabatic electron detachment Gibbs free energy ∆GD,s.

X•(n−1)−(Mm+)pn(Xn−)pm−1‡(g) denotes the ion cluster frozen in the initial configuration, whereas the electron-detached anion has been relaxed; X•(n−1)‒(Mm+)pn(Xn−)pm−1(g) denotes the final fully relaxed ion cluster.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Dehydration of Ox2− in high vacuum (base pressure, 1 × 10−6 mbar).

In situ transmission Fourier-transform infrared spectra, showing loss of hydrogen-bonded H2O (stretching ν, 3,050–3,600 cm−1; bending δ, 1,640 cm−1) accompanied by red shift of both the symmetric stretching νs and anti-symmetric stretching νa COO modes of Ox2− (marked by green dashed lines). The initial hydration level in nominally dry nitrogen (pH2O, 1–10 p.p.m.) is about 4 H2O per Ox2−. Electron doping does not occur until the hydration level decreases below 0.5 H2O per Ox2−. Dehydration occurs slowly in thick films. The thickness of the N3(Ox) film was 1.1 µm. HV, high vacuum.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Evidence for photosensitized electron doping of N3 by Ox2−.

a, In situ transmission optical spectroscopy showing growth of the P2 polaron band in N3(Ox) film with exposure to 365-nm radiation. This wavelength is absorbed by the semiconductor core, but not by Ox2−. The upper plot is a 5 × magnification of the same data up to 2.7 eV that more clearly show the evolution of the P2 band with time (indicatedby arrow). The final saturation doping level is about 0.05 electrons per repeat unit. b, In situ transmission infrared spectroscopy, showing growth of the P1 polaron band and infrared active vibration (IRAV) bands with exposure to 365-nm UV light . The dose required to n-dope this thick film is considerably larger than for the thin film owing to the inner-filter effect. One dose unit is 80 mJ cm−2. The vacuum base pressure is 1 × 10−6 mbar.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Comparative ground-state and photosensitized electron doping of N2 by anions.

a, In situ transmission optical spectroscopy of N2(X) films in dry nitrogen (N2; pH2O, 1 p.p.m.), after high-vacuum pumping (HV; base pressure of 1 × 10−6 mbar for 2 h) and after exhaustive in situ irradiation at 365-nm wavelength (UV; 1.2 J cm−2). The plots in the X=TfO panel have been vertically demagnified by a factor of 4. b, Difference spectra, showing the red shift of the π‒π∗ band upon drying, and the emergence of the 2.0-eV P2 polaron band with breaching of the 2.7-eV π‒π∗ band upon doping. The plots in the X=Ox panel have been vertically demagnified by a factor of 2; those in the X=TfO panel by a factor of 4. The spectra were obtained at a temperature of 295 K.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Evidence for electron doping from UV photoemission spectroscopy.

The vacuum work function is computed from the difference in photoelectron kinetic energies at the Fermi level (KFL) and at the low-energy cutoff (KLECO), that is, the work function is given by KLECO + hν − KFL, where hν is the photon energy (21.21 eV). The work functions for N3(X) are: Ox, 2.95 eV; CO3, 3.75 eV; SO3, 3.85 eV; AcO, 4.1 eV; SO4, 4.1 eV; and TfO, 4.85 eV. Relative to TfO, the work function shifts for Ox, CO3 and SO3 are −1.9 eV, −1.1 eV and −1.0 eV, respectively. The relative binding-energy shifts (measured from the Fermi level for C 1s and other core levels) are even larger: +2.0 eV, +1.55 eV and +1.4 eV, respectively. This indicates strong electron doping of the N3(Ox) film and weaker doping in the other films.The results also suggest the presence of a partially counteracting dipole at the surface of the films (negative on the outside). In the weakly-doped regime, the work function varies very strongly with the doping level34.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Quenching of Ox2− donor strength by added Cs2Ox salt in N5(Ox).

Plot of normalized saturation doping level of N5(Ox):Cs2Ox film after exhaustive photosensitized doping, against m/n of the added Cs2Ox. The doping level was determined from the integrated P2 polaron absorption band intensity at 2.05 eV, together with loss of the π–π∗ band intensity, and normalized to the saturation doping level attained without the added salt, which is 0.01 electrons per repeat unit. The added Cs2Ox increases the size of the ion clusters. The blue line is a guide to the eye.

Extended Data Fig. 12 Organic solar cell characteristics for N2(X) electron collection layers.

Plot of cell parameters against solar irradiation time. From top to bottom, the data show the open-circuit voltage (Voc), fill factor (FF), short-circuit current density (Jsc) and power conversion efficiency (PCE). The first data point at 0.5 min corresponds to the first measurement, given also in Fig. 5b. After a first continual exposure period of 10 h, the device was stored in the dark in nitrogen for 75 h, then re-measured in a second light-soak period to probe recoverability. The standard error is smaller than the symbol size. The irradiance is 100 mW cm−2 with an AM1.5 spectrum. The solar cells with multivalent anions are high-performance, robust and well behaved; those with mono-anions are lower performance, but improves slowly with light soak, albeit with partial reversibility in the dark. The light-soaking-induced improvement in FF lags the improvement in Voc and Jsc, probably as a consequence of the charge-extraction contact resistance that still remains at an insufficiently doped collection contact. The key for the coloured Xn− data points in all panels is given in the first panel of the fill factor row.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary tables of electron detachment energies for anions and their hydrated complexes in gas phase and solid state. (i) Table 1: Experimental and theoretical results for the gas phase from literature, (ii) Table 2: Theoretical results for the gas phase computed in the present work, (iii) Table 3: Corrections for the solid state with ion clusters embedded in an organic matrix, (iv) Table 4: Corrections for the `kinetic’ donor level due to irreversibility.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, C.G., Syafiqah, M.N., Koh, QM. et al. Multivalent anions as universal latent electron donors. Nature 573, 519–525 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1575-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1575-7

This article is cited by

-

N-type conjugated polyelectrolyte enabled by in situ self-doping during aldol condensation

Polymer Journal (2023)

-

Water binding and hygroscopicity in π-conjugated polyelectrolytes

Nature Communications (2023)

-

A solution-processed n-type conducting polymer with ultrahigh conductivity

Nature (2022)

-

A polymer electrolyte design enables ultralow-work-function electrode for high-performance optoelectronics

Nature Communications (2022)

-

In situ-formed tetrahedrally coordinated double-helical metal complexes for improved coordination-activated n-doping

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.