Abstract

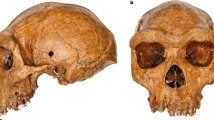

Two fossilized human crania (Apidima 1 and Apidima 2) from Apidima Cave, southern Greece, were discovered in the late 1970s but have remained enigmatic owing to their incomplete nature, taphonomic distortion and lack of archaeological context and chronology. Here we virtually reconstruct both crania, provide detailed comparative descriptions and analyses, and date them using U-series radiometric methods. Apidima 2 dates to more than 170 thousand years ago and has a Neanderthal-like morphological pattern. By contrast, Apidima 1 dates to more than 210 thousand years ago and presents a mixture of modern human and primitive features. These results suggest that two late Middle Pleistocene human groups were present at this site—an early Homo sapiens population, followed by a Neanderthal population. Our findings support multiple dispersals of early modern humans out of Africa, and highlight the complex demographic processes that characterized Pleistocene human evolution and modern human presence in southeast Europe.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Change history

12 July 2019

This article was amended to include the Peer review information, which was missing originally from the Additional Information section.

References

Dennell, R. W., Martinón-Torres, M. & Bermúdez de Castro, J. M. Hominin variability, climatic instability and population demography in Middle Pleistocene Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 1511–1524 (2011).

Tourloukis, V. & Harvati, K. The Palaeolithic record of Greece: a synthesis of the evidence and a research agenda for the future. Quat. Int. 466, 48–65 (2018).

Roksandic, M., Radović, P. & Lindal, J. Revising the hypodigm of Homo heidelbergensis: a view from the Eastern Mediterranean. Quat. Int. 466, 66–81 (2018).

Pitsios, T. K. Paleoanthropological research at the cave site of Apidima and the surrounding region (South Peloponnese, Greece). Anthropol. Anz. 57, 1–11 (1999).

Bartsiokas, A., Arsuaga, J. L., Aubert, M. & Grün, R. U-series dating and classification of the Apidima 2 hominin from Mani Peninsula, Southern Greece. J. Hum. Evol. 109, 22–29 (2017).

Harvati, K., Stringer, C. & Karkanas, P. Multivariate analysis and classification of the Apidima 2 cranium from Mani, Southern Greece. J. Hum. Evol. 60, 246–250 (2011).

Liritzis, Y. & Maniatis, Y. ESR experiments on quaternary calcites and bones for dating purposes. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 129, 3–21 (1989).

Rondoyanni, T., Mettos, A. & Georgiou, C. Geological–morphological observations in the greater Oitilo-Diros area, Mani. Acta Anthropol. 1, 93–102 (1995).

Coutselinis, A., Dritsas, C. & Pitsios, T. K. Expertise médico-légale du crâne pléistocène LAO1/S2 (Apidima II), Apidima, Laconie, Grèce. L’Anthropologie 95, 401–408 (1991).

Arsuaga, J. L. et al. Neandertal roots: cranial and chronological evidence from Sima de los Huesos. Science 344, 1358–1363 (2014).

Stringer, C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 371, 20150237 (2016).

Galway-Witham, J. & Stringer, C. How did Homo sapiens evolve? Science 360, 1296–1298 (2018).

Harvati, K. in Handbook of Paleoanthropology (eds Henke, W. & Tattersall, I.) 2243–2279 (Springer, 2015).

Balzeau, A. & Rougier, H. Is the suprainiac fossa a Neandertal autapomorphy? A complementary external and internal investigation. J. Hum. Evol. 58, 1–22 (2010).

Verna, C., Hublin, J.-J., Debenath, A., Jelinek, A. & Vandermeersch, B. Two new hominin cranial fragments from the Mousterian levels at La Quina (Charente, France). J. Hum. Evol. 58, 273–278 (2010).

Bräuer, G. & Leakey, R. L. The ES-11693 cranium from Eliye Springs, West Turkana, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 15, 289–312 (1986).

Gunz, P. et al. Neandertal introgression sheds light on modern human endocranial globularity. Curr. Biol. 29, 120–127 (2019).

Hublin, J.-J. et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 546, 289–292 (2017).

Hublin, J.-J. The origin of Neandertals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16022–16027 (2009).

Caspari, R. The Krapina occipital bones. Period. Biol. 108, 299–307 (2006).

Arsuaga, J. L., Martínez, I., Gracia, A. & Lorenzo, C. The Sima de los Huesos crania (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). A comparative study. J. Hum. Evol. 33, 219–281 (1997).

Prossinger, H. et al. Electronic removal of encrustations inside the Steinheim cranium reveals paranasal sinus features and deformations, and provides a revised endocranial volume estimate. Anat. Rec. 273B, 132–142 (2003).

Posth, C. et al. Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals. Nat. Commun. 8, 16046 (2017).

Mercier, N. et al. Thermoluminescence date for the Mousterian burial site of Es-Skhul, Mt. Carmel. J. Archaeol. Sci. 20, 169–174 (1993).

Hershkovitz, I. et al. The earliest modern humans outside Africa. Science 359, 456–459 (2018).

Stringer, C. & Galway-Witham, J. When did modern humans leave Africa? Science 359, 389–390 (2018).

Harvati, K., Panagopoulou, E. & Karkanas, P. First Neanderthal remains from Greece: the evidence from Lakonis. J. Hum. Evol. 45, 465–473 (2003).

Harvati, K. et al. New Neanderthal remains from Mani peninsula, Southern Greece: the Kalamakia Middle Paleolithic cave site. J. Hum. Evol. 64, 486–499 (2013).

Tourloukis, V. et al. New Middle Paleolithic sites from the Mani peninsula, Southern Greece. J. Field Archaeol. 41, 68–83 (2016).

Elefanti, P., Panagopoulou, E. & Karkanas, P. The transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic in the Southern Balkans: the evidence from Lakonis 1 Cave, Greece. Eurasian Prehistory 5, 85–95 (2008).

Douka, K., Perlès, C., Valladas, H., Vanhaeren, M. & Hedges, R. E. M. Francthi Cave revisited: the age of the Aurignacian in south-eastern Europe. Antiquity 85, 1131–1150 (2011).

Lowe, J. et al. Volcanic ash layers illuminate the resilience of Neanderthals and early modern humans to natural hazards. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13532–13537 (2012).

De Lumley, M. A. Les Restes Humains Anténéanderthaliens Apidima 1 et Apidima 2 (CNRS, 2019).

Kormasopoulou-Kagalou, L., Protonotariou-Deilaki, E. & Pitsios, T. K. Paleolithic skull burials at the cave of Apidima. Acta Anthropol. 1, 119–124 (1995).

Zollikofer, C. P. et al. Virtual cranial reconstruction of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Nature 434, 755–759 (2005).

Gunz, P., Mitteroecker, P., Neubauer, S., Weber, G. W. & Bookstein, F. L. Principles for the virtual reconstruction of hominin crania. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 48–62 (2009).

Harvati, K., Hublin, J.-J. & Gunz, P. Evolution of middle–late Pleistocene human cranio-facial form: a 3-D approach. J. Hum. Evol. 59, 445–464 (2010).

Harvati, K., Gunz, P. & Grigorescu, D. Cioclovina (Romania): affinities of an early modern European. J. Hum. Evol. 53, 732–746 (2007).

Slice, D. E. Morpheus et al., Java Edition. http://morphlab.sc.fsu.edu/ (The Florida State University, 2013).

Mardia, K. V., Bookstein, F. L. & Moreton, I. J. Statistical assessment of bilateral symmetry of shapes. Biometrika 87, 285–300 (2000).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008).

Claude, J. Morphometrics with R (Springer Science & Business Media, 2008).

Schlager, S. in Statistical Shape and Deformation Analysis (eds Zheng, G. et al.) 217−256 (Academic, 2017).

Bookstein, F. L. Landmark methods for forms without landmarks: morphometrics of group differences in outline shape. Med. Image Anal. 1, 225–243 (1997).

O’Higgins, P. & Jones, N. Morphologika: Tools for Shape Analysis. Version 2.2 https://sites.google.com/site/hymsfme/resources (Hull York Medical School, 2006).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electronica 4, 1–9 (2001).

Field, A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS (Sage, 2013).

Brown, P. Nacurrie 1: mark of ancient Java, or a caring mother’s hands, in terminal Pleistocene Australia? J. Hum. Evol. 59, 168–187 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC CoG no. 724703) and the German Research Foundation (DFG FOR 2237). We thank all curators and their institutions for access to original specimens or casts used in this study; T. White, B. Asfaw, M. López-Soza, V. Tourloukis, D. Giusti, G. Konidaris, C. Fardelas and O. Stolis for their input and assistance; A. Balzeau (Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle; MNHN), E. Delson (New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology; NYCEP), L. Leakey (africanfossils.org) for providing access to three-dimensional models of specimens used in our figures. C.S.’s research is supported by the Calleva Foundation and the Human Origins Research Fund. We are grateful to S. Benazzi, E. Delson and I. Hershkovitz for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H., M.K. and V.G.G. designed the research; V.K. and L.A.M. carried out the computed tomography scans; C.R. and A.M.B. generated the virtual reconstructions; K.H., C.S. and C.R. collected comparative data; K.H., C.R., A.M.B., F.A.K. and N.C.T. processed and analysed the data; R.G. dated the specimens; P.K. and R.G. provided stratigraphic and geological interpretations; all authors contributed to compiling the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peer review information Nature thanks Stefano Benazzi, Eric Delson and Israel Hershkovitz for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Extended data figures and tables

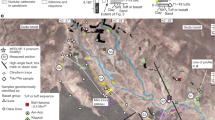

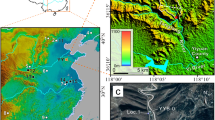

Extended Data Fig. 1 The depositional setting of the Apidima 1 and Apidima 2 specimens.

a, The interior of Apidima Cave A, with the ‘skull breccia’ (red box) before its removal from the cave, shown wedged between the cave walls and near the ceiling. A cross-section of the Apidima 1 cranium can be seen in the bottom left corner of the red box. Note the bedded appearance of the breccia remnant (black dashed line) consisting of different clast sizes and distribution similar to those seen in the talus cone outside the cave in c. b, Cast of the ‘skull breccia’ in the early stages of preparation and cleaning. Apidima 1 is seen on the left, Apidima 2 on the right. c, View of the Apidima site from the sea. Images courtesy and copyright of the Museum of Anthropology, Medical School, National Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Additional views of Apidima 2.

a, Posterior view. b, Superior view. c, Inferior view. Scale bar, 5 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Main steps of reconstruction of Apidima 2.

a–c, Images are the computed surface of the original fossil (a), all segmented fragments (b) and reconstruction 1 from an anterior-superior view (c); segmented fragments are shown in colour and mirrored fragments in grey.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Four manual reconstructions of Apidima 2.

Top row, reconstruction 1 (made by C.R., mirroring criterion). Second row, reconstruction (made by C.R., smoothness criterion). Third row, reconstruction 3 (made by A.B., mirroring criterion). Bottom row, reconstruction 4 (made by A.B., smoothness criterion). Scale bar, 3 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Main steps of reconstruction of Apidima 1.

a–d, Images are the computed surface of the original fossil (a), the cropped scan volume (b), the duplicated and mirrored scan volume (c) and the complete reconstruction (d).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Lateral and posterior views of the parietal region of the four manual reconstructions of Apidima 2.

Images as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. a, Reconstruction 1 (made by C.R., mirroring criterion). b, Reconstruction 2 (made by C.R., smoothness criterion). c, Reconstruction 3 (made by A.B., mirroring criterion). d, Reconstruction 4 (made by A.B., smoothness criterion).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Posterior cranial morphology.

a, b, Posterior and lateral views of the Apidima 1 reconstruction. c, d, Posterior and lateral views of Apidima 2 reconstruction 1. e, f, Posterior and lateral views of the three-dimensional model of La Chapelle-aux-Saints (Neanderthal). g, h, Posterior and lateral views of the three-dimensional model of La Ferrassie 1 (Neanderthal). e–h, Images courtesy of A. Balzeau (MHNH). i, j, Posterior and lateral views of Elandsfontein (MPA). Images courtesy of C.S. k, l, Posterior and lateral views of the three-dimensional model of Sima de los Huesos Cranium 5, cast (MPE). Images courtesy of E. Delson (NYCEP). m, n, Posterior and lateral views of Skhul 5 (H. sapiens). Images courtesy of C.S. o, p, Posterior and lateral views of the three-dimensional model of Eliye Springs (MPA). Images reproduced with permission from https://africanfossils.org/. Scale bar, 5 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Midsagittal profile shape index.

Values calculated from the dataset used in analysis 4 (midsagittal posterior cranial profile), based on the axis between the mean Neanderthal and mean modern African shape. Apidima 1 and the remaining fossil samples are projected onto this axis. Violins extend from the minimum to the maximum value; boxes show the 25–75% quartiles and lines indicate the median. Samples as in Fig. 3b, symbols as in Fig. 2; modern Africans, green dots (n = 15).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Apidima 1 reconstruction superimposed manually with Apidima 2 reconstruction 1.

Aidima 1 is shown in yellow; Apidima 2 is shown in rainbow. a, Lateral view. b, Posterior view. c, Ventral view.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text Sections 1-4, including Supplementary Figures S1-S2 and Supplementary Tables S1-9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harvati, K., Röding, C., Bosman, A.M. et al. Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia. Nature 571, 500–504 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z

This article is cited by

-

Modern humans in Northeast Asia

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

The Persian plateau served as hub for Homo sapiens after the main out of Africa dispersal

Nature Communications (2024)

-

The Middle Pleistocene human metatarsal from Sedia del Diavolo (Rome, Italy)

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Initial Upper Palaeolithic material culture by 45,000 years ago at Shiyu in northern China

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

Virtual excavation and analysis of the early Neanderthal cranium from Altamura (Italy)

Communications Biology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.