Abstract

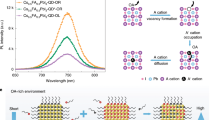

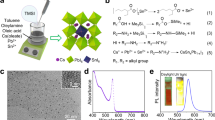

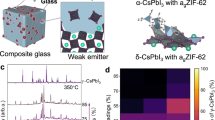

The stability of solution-processed semiconductors remains an important area for improvement on their path to wider deployment. Inorganic caesium lead halide perovskites have a bandgap well suited to tandem solar cells1 but suffer from an undesired phase transition near room temperature2. Colloidal quantum dots (CQDs) are structurally robust materials prized for their size-tunable bandgap3; however, they also require further advances in stability because they are prone to aggregation and surface oxidization at high temperatures as a consequence of incomplete surface passivation4,5. Here we report ‘lattice-anchored’ hybrid materials that combine caesium lead halide perovskites with lead chalcogenide CQDs, in which lattice matching between the two materials contributes to a stability exceeding that of the constituents. We find that CQDs keep the perovskite in its desired cubic phase, suppressing the transition to the undesired lattice-mismatched phases. The stability of the CQD-anchored perovskite in air is enhanced by an order of magnitude compared with pristine perovskite, and the material remains stable for more than six months at ambient conditions (25 degrees Celsius and about 30 per cent humidity) and more than five hours at 200 degrees Celsius. The perovskite prevents oxidation of the CQD surfaces and reduces the agglomeration of the nanoparticles at 100 degrees Celsius by a factor of five compared with CQD controls. The matrix-protected CQDs show a photoluminescence quantum efficiency of 30 per cent for a CQD solid emitting at infrared wavelengths. The lattice-anchored CQD:perovskite solid exhibits a doubling in charge carrier mobility as a result of a reduced energy barrier for carrier hopping compared with the pure CQD solid. These benefits have potential uses in solution-processed optoelectronic devices.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Beal, R. E. et al. Cesium lead halide perovskites with improved stability for tandem solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 746–751 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Stabilizing the α-phase of CsPbI3 perovskite by sulfobetaine zwitterions in one-step spin-coating films. Joule 1, 371–382 (2017).

Liu, M. et al. Hybrid organic–inorganic inks flatten the energy landscape in colloidal quantum dot solids. Nat. Mater. 16, 258–263 (2017).

Zhou, J., Liu, Y., Tang, J. & Tang, W. Surface ligands engineering of semiconductor quantum dots for chemosensory and biological applications. Mater. Today 20, 360–376 (2017).

Keitel, R. C., Weidman, M. C. & Tisdale, W. A. Near-infrared photoluminescence and thermal stability of PbS nanocrystals at elevated temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 20341–20349 (2016).

Mitzi, D. B. Solution-processed inorganic semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 2355–2365 (2004).

García de Arquer, F. P. G., Armin, A., Meredith, P. & Sargent, E. H. Solution-processed semiconductors for next-generation photodetectors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16100 (2017), corrigendum 2, 17012 (2017).

Tan, Z.-K. et al. Bright light-emitting diodes based on organometal halide perovskite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 687–692 (2014).

Shirasaki, Y., Supran, G. J., Bawendi, M. G. & Bulović, V. Emergence of colloidal quantum-dot light-emitting technologies. Nat. Photon. 7, 13–23 (2013).

Xu, J. et al. 2D matrix engineering for homogeneous quantum dot coupling in photovoltaic solids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 456–462 (2018).

Chuang, C.-H. M., Brown, P. R., Bulović, V. & Bawendi, M. G. Improved performance and stability in quantum dot solar cells through band alignment engineering. Nat. Mater. 13, 796–801 (2014).

Christians, J. A. et al. Tailored interfaces of unencapsulated perovskite solar cells for >1,000 hour operational stability. Nat. Energy 3, 68–74 (2018).

Katan, C., Mohite, A. D. & Even, J. Entropy in halide perovskites. Nat. Mater. 17, 377–379 (2018).

Yang, W. S. et al. High-performance photovoltaic perovskite layers fabricated through intramolecular exchange. Science 348, 1234–1237 (2015).

National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Photovoltaic research http://www.nrel.gov/ncpv/images/efficiency_chart.jpg.

Ju, M.-G. et al. Toward eco-friendly and stable perovskite materials for photovoltaics. Joule 2, 1231–1241 (2018).

Eperon, G. E. & Ginger, D. S. B-site metal cation exchange in halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1190–1196 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Surface passivation engineering strategy to fully-inorganic cubic CsPbI3 perovskites for high-performance solar cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 1076 (2018).

Jeong, B. et al. All-inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite phase-stabilized by poly(ethylene oxide) for red-light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706401 (2018).

Xiang, S. et al. The synergistic effect of non-stoichiometry and Sb-doping on air-stable α-CsPbI3 for efficient carbon-based perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 10, 9996–10004 (2018).

Yang, D., Li, X. & Zeng, H. Surface chemistry of all inorganic halide perovskite nanocrystals: passivation mechanism and stability. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1701662 (2018).

Ihly, R., Tolentino, J., Liu, Y., Gibbs, M. & Law, M. The photothermal stability of PbS quantum dot solids. ACS Nano 5, 8175–8186 (2011).

Zhang, X. et al. Inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite coating on PbS quantum dot for highly efficient and stable infrared light converting solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702049 (2018).

Ning, Z. et al. Quantum-dot-in-perovskite solids. Nature 523, 324–328 (2015).

Zhao, D., Huang, J., Qin, R., Yang, G. & Yu, J. Efficient visible–near-infrared hybrid perovskite:PbS quantum dot photodetectors fabricated using an antisolvent additive solution process. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1800979 (2018).

Yang, Z. et al. Colloidal quantum dot photovoltaics enhanced by perovskite shelling. Nano Lett. 15, 7539–7543 (2015).

Dalven, R. Electronic structure of PbS, PbSe, and PbTe. Solid State Phys. 28, 179–224 (1974).

Pinardi, K. et al. Critical thickness and strain relaxation in lattice mismatched II–VI semiconductor layers. J. Appl. Phys. 83, 4724–4733 (1998).

People, R. & Bean, J. C. Calculation of critical layer thickness versus lattice mismatch for GexSi1−x/Si strained-layer heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 47, 322–324 (1985).

Scott, G. D. & Kilgour, D. M. The density of random close packing of spheres. J. Phys. D 2, 863–866 (1969).

Ning, Z. et al. Air-stable n-type colloidal quantum dot solids. Nat. Mater. 13, 822–828 (2014).

de Mello, J. C., Wittmann, H. F. & Friend, R. H. An improved experimental determination of external photoluminescence quantum efficiency. Adv. Mater. 9, 230–232 (1997).

Proppe, A. H. et al. Picosecond charge transfer and long carrier diffusion lengths in colloidal quantum dot solids. Nano Lett. 18, 7052–7059 (2018).

Gilmore, R. H., Lee, E. M. Y., Weidman, M. C., Willard, A. P. & Tisdale, W. A. Charge carrier hopping dynamics in homogeneously broadened PbS quantum dot solids. Nano Lett. 17, 893–901 (2017).

Zhitomirsky, D., Voznyy, O., Hoogland, S. & Sargent, E. H. Measuring charge carrier diffusion in coupled colloidal quantum dot solids. ACS Nano 7, 5282–5290 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This publication is based in part on work supported by an award (OSR-2017-CPF-3321-03) from the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), by the Ontario Research Fund Research Excellence Program, by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada and by the Compute Canada (www.computecanada.ca). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated by Argonne National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357, and resources of the Advanced Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. M. Liu acknowledges financial support from the Hatch Graduate Scholarship for Sustainable Energy Research. The authors thank H. Du, J. Zhang, X. Ma and C. Zou from the Tianjin University for XRD and SEM-EDX measurements. We thank E. Palmiano, L. Levina, R. Wolowiec, D. Kopilovic, M. Wei, J. Choi and Z. Huang from the University of Toronto for their help during the course of study.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Zheng Chen and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. conceived the study and developed the hybrid materials system, fabricated solar cell devices and performed synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements and materials stability tests. Y.C., B. Sun and B. Scheffel assisted in the fabrication of quantum dot in matrix samples. C.-S.T. performed TEM imaging. R.Q.-B. contributed to XPS measurements. A.H.P. carried out transient absorption measurements. R.M. and A.A. carried out in situ GISAXS measurements. H.T. contributed to GIWAXS measurements. G.W. contributed to photoluminescence measurements. A.P.T.K. carried out the mobility measurements. M.-J.C. performed SEM imaging and EDX analysis. O.V., F.P.G.A., S.O.K. and E.H.S. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Morphology of CQD:perovskite hybrid films.

a, Photographs of as-prepared CsPbBr2I films with 0, 10 and 20 vol% of CQDs (from left to right). b, Photographs of as-prepared CsPbBrI2 films with 0, 10 and 20 vol% of CQDs (from left to right). c–f, SEM images of the pure CsPbBr2I film (c) and CQD:CsPbBr2I hybrid films with 10 vol% (d), 20 vol% (e) and 33 vol% (f) CQD. At low CQD loading (10 vol%), no significant changes were observed in grain size. This argues against a main role for grain size on stability. When CQD loading is higher than 20 vol%, a smaller grain size is observed, which is consistent with the XRD peak broadening shown in Fig. 1c.

Extended Data Fig. 2 EDX mapping and elemental analysis of CQD:CsPbBr2I hybrid films.

a–c, EDX mapping of CsPbBr2I films with 10 vol% (a), 20 vol% (b) and 33 vol% (c) CQDs. d–f, Elemental analysis of films in a–c, respectively. An aluminium specimen holder was used for the measurement, resulting in a strong Al signal in the EDX analysis. The energy peak of AlKα (1.486 keV) overlaps with BrLα (1.480 keV) in the EDX spectra. To avoid sample damage, an accelerating voltage of 10 keV was used, which is unable to detect the signal from BrKα (11.922 keV). As a result, we cannot ascertain the elemental ratio of Br in the film. The values from the experiments and calculations are presented in the inset tables. The elemental ratios are normalized to Pb.

Extended Data Fig. 3 X-ray diffraction of the CQD:CsPbBr2I films.

a, Two-dimensional GIWAXS patterns of CQD:CsPbBr2I films. b, Azimuthal integrated line profile along the qz axis.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Morphological and structural characterization of CQD:perovskite hybrid structures.

a, b, HRTEM (a) and fast Fourier transform (b) images of PbS quantum dots with a thin CsPbBrI2 perovskite shell. The shell has a lower contrast than the CQDs, as CsPbX3 has a lower density than PbS. c, d, Scanning TEM images and EELS elemental mapping of a CQD/CsPbBrI2 core–shell structure (c) and a CQD-in-CsPbBrI2-matrix structure (d).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Stability studies of lattice-anchored and control materials system.

a, Stability of the lattice-anchored perovskite with mixed halides. The film stability is improved from a couple of days to several months. For Br content higher than 33%, the perovskite film could be stabilized in room ambient conditions for more than 6 months without any degradation. b, Stability of the lattice-anchored α-phase CsPbI3. The fabrication of CsPbI3 films follows a reported method (ref. 2), which exhibits 1,000-h air stability for the pure perovskite matrix. CQDs further enhanced the stability to greater than 6 months, showing the compatibility of this strategy with previous methods. c, d, Thermal stability studies of methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) films with and without CQDs, as a control material. Absorption spectra of pure MAPbI3 (c) and MAPbI3 with 10 vol% CQDs (d) before and after annealing in ambient air. The degradation of MAPbI3 perovskite arises from the volatility of organic components. The CQD:MAPbI3 film does not show any improvement in thermal stability compared with pure MAPbI3. The reduced and broadened excitonic peak of PbS shows an increase in CQD aggregation.

Extended Data Fig. 6 GISAXS 2D pattern of the matrix-protected CQD films and pristine films measured at room temperature.

a, Matrix-protected CQD film. b, Pristine film.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Photophysical studies of CQD-in-matrix hybrid films.

a, Absorption spectra of CsPbBrI2 film with and without CQDs embedded. b, PL quenching at perovskite emission range. When CQDs are embedded, the PL signal from perovskite is completely quenched, showing an efficient carrier transfer from the matrix to the CQDs. c, PL quantum yield of CQD-in-matrix films at different CQD ratios.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Mobility studies of matrix-protected CQD films and pristine CQDs from the dependence of the carrier lifetime on trap percentage.

a, c, Time traces at the exciton bleach peak of 960-nm-bandgap CQD donor films with a range of acceptor CQD concentrations, increasing from top (0%) to bottom (5%). b, d, Data with fits after subtracting Auger dynamics from the pure donor film, with fitted values for lifetime and offset. A, absorption.

Extended Data Fig. 9 CQD solar cell devices.

a, Device architecture. b–d, Solar cell performance. Dark blue curves represent the matrix-infiltrated CQD samples, and the light blue curves represent the pure CQD samples. b, Current density versus voltage (J–V) curves. c, EQE. d, Stability test with continuous AM1.5G illumination unencapsulated. oc, open circuit; sc, short circuit; FF, fill factor; MPP, maximum power point.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Chen, Y., Tan, CS. et al. Lattice anchoring stabilizes solution-processed semiconductors. Nature 570, 96–101 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1239-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1239-7

This article is cited by

-

TiO2 Electron Transport Layer with p–n Homojunctions for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells

Nano-Micro Letters (2024)

-

Fluoride passivation of ZnO electron transport layers for efficient PbSe colloidal quantum dot photovoltaics

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2023)

-

How to get high-efficiency lead chalcogenide quantum dot solar cells?

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Epitaxial growth of highly symmetrical branched noble metal-semiconductor heterostructures with efficient plasmon-induced hot-electron transfer

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Lattice strain suppresses point defect formation in halide perovskites

Nano Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.