Abstract

Hybrid classical–quantum algorithms aim to variationally solve optimization problems using a feedback loop between a classical computer and a quantum co-processor, while benefiting from quantum resources. Here we present experiments that demonstrate self-verifying, hybrid, variational quantum simulation of lattice models in condensed matter and high-energy physics. In contrast to analogue quantum simulation, this approach forgoes the requirement of realizing the targeted Hamiltonian directly in the laboratory, thus enabling the study of a wide variety of previously intractable target models. We focus on the lattice Schwinger model, a gauge theory of one-dimensional quantum electrodynamics. Our quantum co-processor is a programmable, trapped-ion analogue quantum simulator with up to 20 qubits, capable of generating families of entangled trial states respecting the symmetries of the target Hamiltonian. We determine ground states, energy gaps and additionally, by measuring variances of the Schwinger Hamiltonian, we provide algorithmic errors for the energies, thus taking a step towards verifying quantum simulation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated and analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The optimization algorithm developed during this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

03 April 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Gross, C. & Bloch, I. Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Science 357, 995–1001 (2017).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017).

Labuhn, H. et al. Tunable two-dimensional arrays of single Rydberg atoms for realizing quantum Ising models. Nature 534, 667–670 (2016).

Britton, J. W. et al. Engineered two-dimensional Ising interactions in a trapped-ion quantum simulator with hundreds of spins. Nature 484, 489–492 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator. Nature 551, 601–604 (2017).

Blatt, R. & Roos, C. F. Quantum simulations with trapped ions. Nature Phys. 8, 277–284 (2012).

Houck, A. A., Türeci, H. E. & Koch, J. On-chip quantum simulation with superconducting circuits. Nature Phys. 8, 292–299 (2012).

Zache, T. V. et al. Quantum simulation of lattice gauge theories using Wilson fermions. Quant. Sci. Technol. 3, 034010 (2018).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Universal digital quantum simulation with trapped ions. Science 334, 57–61 (2011).

Martinez, E. A. et al. Real-time dynamics of lattice gauge theories with a few-qubit quantum computer. Nature 534, 516–519 (2016).

Salathé, Y. et al. Digital quantum simulation of spin models with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021027 (2015).

McClean, J. R., Romero, J., Babbush, R. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. New J. Phys. 18, 023023 (2016).

Moll, N. et al. Quantum optimization using variational algorithms on near-term quantum devices. Quant. Sci. Technol. 3, 030503 (2018).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Report number MIT-CTP/4610. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.4028 (2014).

O’Malley, P. J. J. et al. Scalable quantum simulation of molecular energies. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031007 (2016).

Otterbach, J. S. et al. Unsupervised machine learning on a hybrid quantum computer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05771 (2017).

Hempel, C. et al. Quantum chemistry calculations on a trapped-ion quantum simulator. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031022 (2018).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nature Commun. 5, 4213 (2014).

Dumitrescu, E. F. et al. Cloud quantum computing of an atomic nucleus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 210501 (2018).

Kandala, A. et al. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 549, 242–246 (2017).

Klco, N. et al. Quantum-classical computations of Schwinger model dynamics using quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 98, 032331 (2018).

Wecker, D., Hastings, M. B. & Troyer, M. Progress towards practical quantum variational algorithms. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042303 (2015).

Yang, Z.-C., Rahmani, A., Shabani, A., Neven, H. & Chamon, C. Optimizing variational quantum algorithms using Pontryagin’s minimum principle. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021027 (2017).

Pichler, H., Wang, S.-T., Zhou, L., Choi, S. & Lukin, M. D. Quantum optimization for maximum independent set using Rydberg atom arrays. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.10816 (2018).

Carleo, G. & Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 355, 602–606 (2017).

Lloyd, S. & Montangero, S. Information theoretical analysis of quantum optimal control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 010502 (2014).

Schwinger, J. Gauge invariance and mass. II. Phys. Rev. 128, 2425–2429 (1962).

Hamer, C., Kogut, J., Crewther, D. & Mazzolini, M. The massive Schwinger model on a lattice: background field, chiral symmetry and the string tension. Nucl. Phys. B 208, 413–438 (1982).

Brydges, T. & Elben, A. et al. Probing Rényi entanglement entropy via randomized measurements. Science 364, 260–263 (2019).

Kim, K. et al. Entanglement and tunable spin-spin couplings between trapped ions using multiple transverse modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 120502 (2009).

Richerme, P. et al. Non-local propagation of correlations in quantum systems with long-range interactions. Nature 511, 198–201 (2014).

Jurcevic, P. et al. Quasiparticle engineering and entanglement propagation in a quantum many-body system. Nature 511, 202–205 (2014).

Schwinger, J. The theory of quantized fields. I. Phys. Rev. 82, 914–927 (1951).

Hamer, C. J., Weihong, Z. & Oitmaa, J. Series expansions for the massive Schwinger model in Hamiltonian lattice theory. Phys. Rev. D 56, 55–67 (1997).

Jordan, S. P., Lee, K. S. M. & Preskill, J. Quantum algorithms for quantum field theories. Science 336, 1130–1133 (2012).

Jones, D. R., Perttunen, C. D. & Stuckman, B. E. Lipschitzian optimization without the Lipschitz constant. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 79, 157–181 (1993).

Liu, H., Xu, S., Wang, X., Wu, J. & Song, Y. A global optimization algorithm for simulation-based problems via the extended direct scheme. Engin. Optim. 47, 1441–1458 (2015).

Nicholas, P. E. A dividing rectangles algorithm for stochastic simulation optimization. Proc. INFORMS Comput. Soc. Conf. 14, 47–61 (2014).

Colless, J. I. et al. Computation of molecular spectra on a quantum processor with an error-resilient algorithm. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011021 (2018).

Byrnes, T., Sriganesh, P., Bursill, R. & Hamer, C. Density matrix renormalization group approach to the massive Schwinger model. Nucl. Phys. B 109, 202–206 (2002).

Doria, P., Calarco, T. & Montangero, S. Optimal control technique for many-body quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 190501 (2011).

Cirac, J. I. & Sierra, G. Infinite matrix product states, conformal field theory, and the Haldane-Shastry model. Phys. Rev. B 81, 104431 (2010).

Jordan, J., Orús, R., Vidal, G., Verstraete, F. & Cirac, J. I. Classical simulation of infinite-size quantum lattice systems in two spatial dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 250602 (2008).

Giovannetti, V., Montangero, S. & Fazio, R. Quantum multiscale entanglement renormalization ansatz channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 180503 (2008).

Weimer, H., Müller, M., Lesanovsky, I., Zoller, P. & Büchler, H. P. A Rydberg quantum simulator. Nature Phys. 6, 382–388 (2010).

Chiu, C. S., Ji, G., Mazurenko, A., Greif, D. & Greiner, M. Quantum state engineering of a Hubbard system with ultracold fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 243201 (2018).

Esslinger, T. Fermi-Hubbard physics with atoms in an optical lattice. Ann. Rev. Condensed Matter Phys. 1, 129–152 (2010).

Finkel, D. E. & Kelley, C. Convergence analysis of the direct algorithm. Optim. Online 14, 1–10 (2004).

Tavassoli, A., Hajikolaei, K. H., Sadeqi, S., Wang, G. G. & Kjeang, E. Modification of direct for high-dimensional design problems. Eng. Optim. 46, 810–823 (2014).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning) (MIT Press, 2005).

Li, Y. & Benjamin, S. C. Efficient variational quantum simulator incorporating active error minimization. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021050 (2017).

Fu, M. C., Chen, C.-H. & Shi, L. Some topics for simulation optimization. In Proc. 40th Conf. on Winter Simulation 27–38, https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1516744 (ACM, 2008).

Santagati, R. et al. Witnessing eigenstates for quantum simulation of Hamiltonian spectra. Sci. Adv. 4, 9646 (2018).

Ho, W. W. & Hsieh, T. H. Efficient variational simulation of non-trivial quantum states. SciPost Phys. 6, 029 (2019).

Rico, E., Pichler, T., Dalmonte, M., Zoller, P. & Montangero, S. Tensor networks for lattice gauge theories and atomic quantum simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 201601 (2014).

Buyens, B., Montangero, S., Haegeman, J., Verstraete, F. & Van Acoleyen, K. Finite-representation approximation of lattice gauge theories at the continuum limit with tensor networks. Phys. Rev. D 95, 094509 (2017).

Bañuls, M. C., Cichy, K., Jansen, K. & Cirac, I. The mass spectrum of the Schwinger model with matrix product states. J. High Energy Phys. 11, 158 (2013).

Bañuls, M. C., Cichy, K., Cirac, I., Jansen, K. & Saito, H. Matrix product states for lattice field theories. Proc. Sci. 332, https://pos.sissa.it/187/332/pdf (2013).

van Frank, S. et al. Optimal control of complex atomic quantum systems. Sci. Rep. 6, 34187 (2016).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Efficient tomography of a quantum many-body system. Nature Phys. 13, 1158–1162 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Bollinger, A. Elben, K. Holmström, K. Jansen, M. Lukin, E. A. Martinez, S. Montangero, P. Schindler and U. J. Wiese for discussions. The numerical results presented were achieved (in part) using the HPC infrastructure LEO of the University of Innsbruck. The research at Innsbruck is supported by the ERC Synergy Grant UQUAM, by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 741541, by the SFB FoQuS (FWF project number F4016-N23) and by QTFLAG—QuantERA. This project (or publication) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 817482 (PASQuanS). We thank A. Elben and B. Vermersch for the development of the software used for evaluating the Rényi entropies measurement.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Juergen Berges, Christof Wunderlich and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research topic was developed by C.K., R.v.B., C.A.M., P.S. and C.F.R. (following a suggestion by P.Z.). C.K., R.v.B., P.S. and P.Z. developed the theoretical protocols. Software for the classical-quantum feedback loop and classical simulations was developed by R.v.B. and C.K. C.M., M.K.J., T.B., P.J., C.F.R. and R.B. contributed to the experimental setup. Experimental data were taken by C.M., T.B., P.J. and M.K.J. R.v.B., C.K., C.M., C.A.M., P.S., C.F.R. and P.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Energy minimization for 16 ions.

a, Experimentally measured energies \({E}^{(0)}({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{i})\equiv \langle \varPsi ({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{i})|{\hat{H}}_{{\rm{T}}}|\varPsi ({{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}_{i})\rangle \) (upper panel, dots) in the course of a single optimization run for 16 ions, plotted versus iteration number i of the DIRECT optimization algorithm (see text), for \(m=0.6,w= {\bar{g}} =1\). Energy values E(0)(θi) are colour-coded to indicate the Euclidean distance of θi to the final optimized parameter vector θopt, as selected by theoretical fidelity. The solid red line indicates the algorithm’s current estimate of the ground-state energy and its 2σ uncertainty (shaded area), from modelling the energies observed so far as jointly Gaussian distributed random variables (Methods). The inset shows a close-up of a late stage of the optimization, where statistical error bars (Methods) are displayed, and theoretically simulated values are plotted as crosses. The lower panel of a displays the theoretically calculated fidelities \({\mathscr{F}}\) corresponding to the experimentally applied parameters θi. b, Visualization of the energy landscape. Sampled energies are plotted as a function of their distance in the 15-dimensional parameter space \(| \Delta {\boldsymbol{\theta }}| \) relative to the optimal point θopt, and the cell size that each sampling point represents in the DIRECT algorithm (Methods). The algorithm encountered several local minima, appearing as distinct ‘fingers’ with low energies at specific parameter distances and extending towards the direction of smaller representative cell sizes, which is indicative of an increasingly dense sampling around each of the local minima.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Analysis of the algorithmic error bar.

The theoretically expected standard deviations of the target Hamiltonians, obtained from a numerically simulated experiment optimizing the ground state for eight ions, are plotted as a function of the bare mass m around the critical point, and of the circuit depth (with \(w= {\bar{g}} =1\). As expected, algorithmic error bars decrease for increasing circuit depth. This is especially visible in proximity of the critical point (orange dots on peaks in the black curves) where the target states are more entangled, requiring deeper circuits to achieve a required precision.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Protection of target model symmetries.

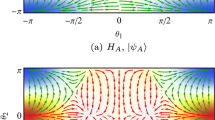

The left-hand panel shows the Schwinger spin model in the Kogut–Susskind formulation, where matter fields are represented by spin degrees of freedom: \({\hat{H}}_{{\rm{T}}}=2w\mathop{\sum }\limits_{n=1}^{N-1}({\hat{\sigma }}_{n}^{x}{\hat{\sigma }}_{n+1}^{x}+{\hat{\sigma }}_{n}^{y}{\hat{\sigma }}_{n+1}^{y})+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}{c}_{i}{\hat{\sigma }}_{i}^{z}+\sum _{i,j > 1}{c}_{ij}{\hat{\sigma }}_{i}^{z}{\hat{\sigma }}_{j}^{z}\). The gauge fields were eliminated using the Gauss law, which results in complicated long-range spin–spin interactions cij (see Supplementary Information section I). The Schwinger Hamiltonian \({ {\hat{H}} }_{{\rm{T}}}\) is block-diagonal with respect to different sectors of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{t}}}^{z}\). Furthermore, the \({\sigma }_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{t}}}^{z}=0\) sector decomposes into two blocks corresponding to quantum numbers \(\hat{{\rm{C}}{\rm{P}}}=+1\) and \(\hat{{\rm{C}}{\rm{P}}}=-1\). We investigate the ground state of \({ {\hat{H}} }_{{\rm{T}}}\) restricted to the symmetry sector with quantum numbers 0 and +1, respectively, for the \({\sigma }_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{t}}}^{z}\) and the \(\widehat{{\rm{C}}{\rm{P}}}\) symmetries. The right-hand panel shows that the native resources on an ion trap platform can be exploited to engineer symmetry-preserving quantum circuits specifically tailored to the Schwinger model. Taking \(B\gg {\rm{\max }}\{| {J}_{ij}| \}\) (equation (3) in the main text), results in an approximate protection of the \({\sigma }_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{t}}}^{z}\) symmetry (see Supplementary Information). Likewise, single-qubit rotations around the z axis can be forced to be \(\widehat{{\rm{C}}{\rm{P}}}\)-symmetric by linking the rotation angles between the left and the right half of the chain according to \({\theta }_{{\ell }}^{n}=-{\theta }_{{\ell }}^{N-n+1}\) (see Supplementary Information). Such a circuit will thus protect the target symmetries, restricting the variational search to be only within the portion of Hilbert space of interest.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measurement scheme.

Strategy for measuring the squared Schwinger Hamiltonian \({ {\hat{H}} }_{T}^{2}\) from single-qubit operations and measurements. This diagram shows the scheme for measuring the remaining components of the anticommutator {ΛX, ΛZ} not present in ΛY (see Supplementary Information section IV). They are four-body correlators of the form \({\hat{\sigma }}_{j}^{x}{\hat{\sigma }}_{j+1}^{x}{\hat{\sigma }}_{{j}^{{\rm{{\prime} }}}}^{z}{\hat{\sigma }}_{{j}^{{\rm{{\prime} }}{\rm{{\prime} }}}}^{z}\), with all Pauli operators acting on different sites. On the experiment, all such correlators for a specific j are obtained by rotating sites j and j + 1 under exp(iπσy/4) and then projective measuring in the canonical basis. The procedure has to be repeated for all j, thus N − 1 times.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Qubit chain encoding of the lattice Schwinger model.

Illustration of a specific product state for eight lattice sites in the Schwinger model and its encoding in the corresponding spin configuration. The curves between sites represent the long-range spin–spin interaction pattern, where the thickness of each curve encodes the coupling strength. The inset shows the encoding of particles into spins, with empty sites (vacuum) denoted by ‘vac’.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Theoretical scalability.

Numerical simulation of the VQS for Schwinger ground states with trapped-ion resources. The infidelity of the optimized ground state with respect to the exact ground state is plotted as a function of the number of qubits N and the circuit depth, or number of circuit layers nlayers. Different panels refer to the simulation of the Schwinger model for different values of the bare mass m, reported via the parametric distance δm = (m − mc) from the critical point mc (for \(w= {\bar{g}} =1\)). The black dashed line marks the minimal circuit depth required to achieve an optimized infidelity of 5% or less, as a function of the system length N.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains and Supplementary Text and Data Sections 1-6 and Supplementary References.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kokail, C., Maier, C., van Bijnen, R. et al. Self-verifying variational quantum simulation of lattice models. Nature 569, 355–360 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1177-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1177-4

This article is cited by

-

Quantum many-body simulations on digital quantum computers: State-of-the-art and future challenges

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Quantum Computing in the Next-Generation Computational Biology Landscape: From Protein Folding to Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Biotechnology (2024)

-

Quantum process tomography with unsupervised learning and tensor networks

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Many-body bound states and induced interactions of charged impurities in a bosonic bath

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Quantum simulation of fundamental particles and forces

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.