Abstract

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the dominant and most consequential climate variation on Earth, and is characterized by warming of equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs) during the El Niño phase and cooling during the La Niña phase. ENSO events tend to have a centre—corresponding to the location of the maximum SST anomaly—in either the central equatorial Pacific (5° S–5° N, 160° E–150° W) or the eastern equatorial Pacific (5° S–5° N, 150°–90° W); these two distinct types of ENSO event are referred to as the CP-ENSO and EP-ENSO regimes, respectively. How the ENSO may change under future greenhouse warming is unknown, owing to a lack of inter-model agreement over the response of SSTs in the eastern equatorial Pacific to such warming. Here we find a robust increase in future EP-ENSO SST variability among CMIP5 climate models that simulate the two distinct ENSO regimes. We show that the EP-ENSO SST anomaly pattern and its centre differ greatly from one model to another, and therefore cannot be well represented by a single SST ‘index’ at the observed centre. However, although the locations of the anomaly centres differ in each model, we find a robust increase in SST variability at each anomaly centre across the majority of models considered. This increase in variability is largely due to greenhouse-warming-induced intensification of upper-ocean stratification in the equatorial Pacific, which enhances ocean–atmosphere coupling. An increase in SST variance implies an increase in the number of ‘strong’ EP-El Niño events (corresponding to large SST anomalies) and associated extreme weather events.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data related to this paper can be downloaded from the following: HadISST v1.1, https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.hadsst.html; ERSST v5, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/marineocean-data/extended-reconstructed-sea-surface-temperature-ersst-v5; OISST v2, https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.html; ORA-s3, http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/datadoc/ecmwf_oras3.php; ORA-s4, https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/oras4-ecmwf-ocean-reanalysis-and-derived-ocean-heat-content; and CMIP5 database, http://www.ipcc-data.org/sim/gcm_monthly/AR5/.

References

Ropelewski, C. F. & Halpert, M. S. Global and regional scale precipitation patterns associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation. Mon. Weath. Rev. 115, 1606–1626 (1987).

Glynn, P. W. & DE Weerdt, W. H. Elimination of two reef-building hydrocorals following the 1982-83 El Niño warming event. Science 253, 69–71 (1991).

Bove, M. C., O’Brien, J. J., Eisner, J. B., Landsea, C. W. & Niu, X. Effect of El Niño on US landfalling hurricanes, revisited. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 2477–2482 (1998).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. Science 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Vincent, E. M. et al. Interannual variability of the South Pacific Convergence Zone and implications for tropical cyclone genesis. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1881–1896 (2011).

Valle, C. A. et al. The impact of the 1982–1983 El Niño-Southern Oscillation on seabirds in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. J. Geophys. Res. 92, 14437–14444 (1987).

Cai, W. et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 111–116 (2014).

Ashok, K., Behera, S. K., Rao, S. A., Weng, H. & Yamagata, T. El Niño Modoki and its possible teleconnection. J. Geophys. Res. 112, C11007 (2007).

Yeh, S.-W. et al. El Niño in a changing climate. Nature 461, 511–514 (2009).

Kug, J.-S., Jin, F.-F. & An, S.-I. Two types of El Niño events: cold tongue El Niño and warm pool El Niño. J. Clim. 22, 1499–1515 (2009).

Kao, H. Y. & Yu, J.-Y. Contrasting eastern-Pacific and central-Pacific types of ENSO. J. Clim. 22, 615–632 (2009).

Takahashi, K., Montecinos, A., Goubanova, K. & Dewitte, B. ENSO regimes: reinterpreting the canonical and Modoki El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L10704 (2011).

Dommenget, D., Bayr, T. & Frauen, C. Analysis of the non-linearity in the pattern and time evolution of El Niño Southern Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2825–2847 (2013).

Takahashi, K. & Dewitte, B. Strong and moderate nonlinear El Niño regimes. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1627–1645 (2016).

Capotondi, A. et al. Understanding ENSO diversity. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 921–938 (2015).

Cai, W. et al. More extreme swings of the South Pacific convergence zone due to greenhouse warming. Nature 488, 365–369 (2012).

Cai, W. et al. ENSO and Greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 849–859 (2015).

Collins, M. et al. The impact of global warming on the tropical Pacific Ocean and El Niño. Nat. Geosci. 3, 391–397 (2010).

Watanabe, M. et al. Uncertainty in the ENSO amplitude change from the past to the future. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L20703 (2012).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Global warming pattern formation: sea surface temperature and rainfall. J. Clim. 23, 966–986 (2010).

Power, S., Delage, F., Chung, C., Kociuba, G. & Keay, K. Robust twenty-first-century projections of El Niño and related precipitation variability. Nature 502, 541–545 (2013).

Santoso, A. et al. Late-twentieth-century emergence of the El Niño propagation asymmetry and future projections. Nature 504, 126–130 (2013).

McPhaden, M. J., Lee, T. & McClurg, D. El Niño and its relationship to changing background conditions in the tropical Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15709 (2011).

Newman, M., Shin, S.-I. & Alexander, M. A. Natural variation in ENSO flavors. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L14705 (2011).

Yeh, S.-W., Kirtman, B. P., Kug, J.-S., Park, W. & Latif, M. Natural variability of the central Pacific El Niño event on multi-centennial timescales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L02704 (2011).

Cai, W. et al. More frequent extreme La Niña events under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 132–137 (2015).

Choi, K.-Y., Vecchi, G. A. & Wittenberg, A. T. ENSO transition, duration, and amplitude asymmetries: role of the nonlinear wind stress coupling in a conceptual model. J. Clim. 26, 9462–9476 (2013).

Frauen, C. & Dommenget, D. El Niño and La Niña amplitude asymmetry caused by atmospheric feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L18801 (2010).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Kim, S. T. & Yu, J.-Y. The two types of ENSO in CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L11704 (2012).

Ham, Y.-G. & Kug, J.-S. How well do current climate models simulate two types of El Nino? Clim. Dyn. 39, 383–398 (2012).

Karamperidou, C., Jin, F.-F. & Conroy, J. L. The importance of ENSO nonlinearities in tropical Pacific response to external forcing. Clim. Dyn. 49, 2695–2704 (2017).

Stevenson, S. et al. Will there be a significant change to El Niño in the twenty-first century? J. Clim. 25, 2129–2145 (2012).

Cane, M. A. & Sarachik, E. S. The response of a linear baroclinic equatorial ocean to periodic forcing. J. Mar. Res. 39, 651–693 (1981).

Zebiak, S. E. & Cane, M. A. A model El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Mon. Weath. Rev. 115, 2262–2278 (1987).

Dewitte, B., Reverdin, G. & Maes, C. Vertical structure of an OGCM simulation of the equatorial Pacific Ocean in 1985–1994. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 29, 1542–1570 (1999).

Dewitte, B. et al. Low frequency variability of temperature in the vicinity of the equatorial thermocline in SODA: role of equatorial wave dynamics and ENSO asymmetry. J. Clim. 22, 5783–5795 (2009).

An, S.-I. & Jin, F.-F. Collective role of thermocline and zonal advective feedbacks in the ENSO mode. J. Clim. 14, 3421–3432 (2001).

Thual, S., Dewitte, B., An, S.-I. & Ayoub, N. Sensitivity of ENSO to stratification in a recharge-discharge conceptual model. J. Clim. 4, 4331–4348 (2011).

Thual, S., Dewitte, B., An, S.-I., Illig, S. & Ayoub, N. Influence of recent stratification changes on ENSO stability in a conceptual model of the equatorial Pacific. J. Clim. 26, 4790–4802 (2013).

Gent, P. R. & Luyten, J. R. How much energy propagates vertically in the equatorial oceans? J. Phys. Oceanogr. 15, 997–1007 (1985).

Kim, W. & Cai, W. The importance of the eastward zonal current for generating extreme El Niño. Clim. Dyn. 42, 3005–3014 (2014).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature version 5 (ERSSTv5), upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. An improved in situ and satellite SST analysis for climate. J. Clim. 15, 1609–1625 (2002).

Balmaseda, M. A., Vidard, A. & Anderson, D. L. T. The ECMWF ocean analysis system: ORA-S3. Mon. Weath. Rev. 136, 3018–3034 (2008).

Balmaseda, M. A., Mogensen, K. & Weaver, A. T. Evaluation of the ECMWF ocean reanalysis system ORAS4. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 139, 1132–1161 (2013).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–472 (1996).

Lorenz, E. N. Empirical Orthogonal Functions and Statistical Weather Prediction. Statistical Forecast Project Report 1 (MIT Department of Meteorology, 1956).

Fjelstad, J. E. Interne Wellen (Cammermeyer in Komm., 1933).

Dewitte, B., Yeh, S.-W., Moon, B.-K., Cibot, C. & Terray, L. Rectification of the ENSO variability by interdecadal changes in the equatorial background mean state in a CGCM simulation. J. Clim. 20, 2002–2021 (2007).

Yeh, S.-W., Dewitte, B., Yim, B. Y. & Noh, Y. Role of the upper ocean structure in the response of ENSO-like SST variability to global warming. Clim. Dyn. 35, 355–369 (2010).

Blumenthal, M. B. & Cane, M. A. Accounting for parameter uncertainties in model verification: an illustration with tropical sea surface temperature. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 19, 815–830 (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Centre for Southern Hemisphere Oceans Research, a joint research centre between QNLM and CSIRO. W.C., G.W. and A.S. are also supported by the Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program, and a CSIRO Office of Chief Executive Science Leader award. B.D. was supported by Fondecyt (grant number 1171861) and LEFE-GMMC. PMEL contribution number: 4817.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Y.-G. Ham and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. conceived the study and wrote the initial manuscript in collaboration with L.W. and B.D. G.W. performed the model analysis and generated the final figures. B.D. analyses the dynamical coupling between the atmosphere and the ocean. A.S., B.D., K.T., A.C., Y.Y. and M.J.M. contributed to interpretation of the results, discussion of the associated dynamics and improvement of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

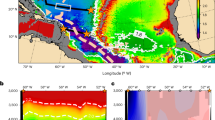

Extended Data Fig. 1 Properties of the observed ENSO diversity, the associated CP and EP regimes, and the nonlinear Bjerknes feedback.

a, b, The diversity means that the pattern of any ENSO event may be reconstructed by a combination of the first (a) and second (b) principal pattern from an EOF analysis on monthly SST anomalies (colour scale) and the associated wind-stress vectors (scale shown top right). The associated monthly PC time series are used to describe their evolution, and the CP- and EP-ENSO regimes by the C-index (\(({\rm{PC}}1+{\rm{PC}}2)/\sqrt{2}\)) and E-index (\(({\rm{PC}}1-{\rm{PC}}2)/\sqrt{2}\)), respectively. c, d, The anomaly pattern associated with the EP-ENSO (c) and CP-ENSO (d) for December–February (DJF), the season in which ENSO events typically mature. e, f, Response to the E-index (e) or C-index (f) of monthly zonal wind-stress (Tauu) anomalies (in units of N m−2) at the anomaly centre (see Methods) associated with the E- or C-index, respectively. The monthly wind-stress anomalies were binned in 0.25-s.d. E- or C-index intervals, and the median wind-stress anomaly and index are identified for each bin (circles). A separate linear regression was carried out for positive (red) and negative (blue) median index values. The ratio of the slope for the positive indices (S2) over that for the negative indices (S1) is taken as an indication of the nonlinear Bjerknes feedback, which operates in the EP-ENSO.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Inter-model relationship between α and the zonal wind response to SST.

a, Relationship between α and the response of monthly zonal wind anomalies to positive E-index values. Zonal wind anomalies are taken at the anomaly centre associated with the E-index. b, Relationship between α and the response of zonal wind anomalies to negative C-index values. Zonal wind anomalies are taken at the anomaly centre associated with the C-index.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Properties of the selected models in terms of ENSO diversity, the associated CP and EP regimes, and the nonlinear Bjerknes feedback.

As in Extended Data Fig. 1, but for only the 17 selected models.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Examples of the nonlinear relationship between the PC1 and PC2 time series in some selected models.

a–d, December–February averages, with an apparent inverted V-shaped nonlinear relationship between PC1 and PC2 for FIO-ESM (a), CCSM4 (b), CESM1-CAM5 (c) and GFDL-ESM2M (d).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Properties of the non-selected models in terms of ENSO diversity, the associated CP and EP regimes, and nonlinear Bjerknes feedback.

As in Extended Data Fig. 3, but for only the 17 non-selected models. In this case, the nonlinear Bjerknes feedback is much weaker.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Examples of the nonlinear relationship between the PC1 and PC2 time series in some non-selected models.

a–d, December–February averages for ACCESS1-3 (a), inmcm4 (b), IPSL-CM5A-MR (c) and bcc-csm1-1 (d). In contrast to the selected models (Extended Data Fig. 4), these models display a weak or no nonlinear relationship between PC1 and PC2.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Histograms of 10,000 realizations of a bootstrap method for the present-day (control) and future (climate change) periods.

Each realization is averaged over 17 models, independently resampled randomly from the 17 selected models. The standard deviation of the 10,000 inter-realization is calculated for each period. a, For the E-index, the standard deviations are 0.0263 (blue) and 0.0234 (red) for the two periods. b, For occurrences with E-index > 1.5 s.d., the standard deviations are 0.87 (blue) and 1.06 (red) for the two periods. c, For the wind-projection coefficient, the standard deviations are 0.036 (blue) and 0.042 (red) for the two periods. The difference between the future and the present-day periods is greater than the sum of the two inter-realization standard deviation values (each indicated by half of the grey shaded region). The blue and red vertical lines indicate the mean values of 10,000 inter-realizations for the present-day and future periods, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Projected change in EP-ENSO variability using the E-index and the Niño3 SST index.

a, Comparison of the standard deviation of the E-index in the present-day (1900–1999) and future (2000–2099) 100-year periods for all 34 models. 24 of the 34 models show an increase in variance (the other 10 are greyed out). b, The same as a, but for the Niño3 SST index. Error bars in the multi-model mean are calculated as the standard deviation of the 10,000 inter-realizations. The multi-model-mean change in the E-index variance (a) is statistically significant at more than the 95% confidence level, but that in the Niño3 SST index is not significant (b). The vertical line separates the selected (left) from the non-selected (right) models.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Relationship between SST warming and change in E-index for selected models.

a, Multi-model-mean warming pattern (in °C per °C of global warming (GW); colour scale). First, for each model we construct a warming pattern by calculating the difference between the average SST anomalies over the future (2000–2099) and present-day (1900–1999) periods. Second, we scale this difference by the increase in global-mean SST simulated by the model over the corresponding period. Finally, we take the mean of the scaled difference over all models to construct the multi-model-mean warming pattern. b, Inter-model relationship between the intensity of the SST warming pattern (a) and change in E-index, also scaled by the corresponding increase in global-mean SST in each model. The intensity of the scaled SST warming pattern for each model is obtained by regressing the scaled SST warming pattern for each model onto the scaled multi-model-mean SST warming pattern, using the region indicated by the black box in a. The inter-model relationship is statistically significant above the 95% confidence level, with the statistical properties shown.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, W., Wang, G., Dewitte, B. et al. Increased variability of eastern Pacific El Niño under greenhouse warming. Nature 564, 201–206 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0776-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0776-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced North Pacific Victoria mode in a warming climate

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2024)

-

Salinity effect-induced ENSO amplitude modulation in association with the interdecadal Pacific Oscillation

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2024)

-

A multiple linear regression model for the prediction of summer rainfall in the northwestern Peruvian Amazon using large-scale indices

Climate Dynamics (2024)

-

Attributing interdecadal variations of southern tropical Indian Ocean dipole mode to rhythms of Bjerknes feedback intensity

Climate Dynamics (2024)

-

Long-term climate change impacts on regional sterodynamic sea level statistics analyzed from the MPI-ESM large ensemble simulation

Climate Dynamics (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.