Abstract

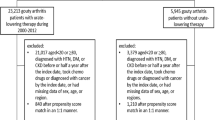

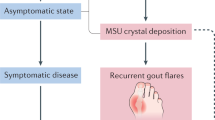

Gout is a common hyperuricaemic metabolic condition that leads to painful inflammatory arthritis and a high comorbidity burden, especially cardiometabolic-renal (CMR) conditions, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, obesity, hyperlipidaemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Substantial advances have been made in our understanding of the excess CMR burden in gout, ranging from pathogenesis underlying excess CMR comorbidities, inferring causal relationships from Mendelian randomization studies, and potentially discovering urate crystals in coronary arteries using advanced imaging, to clinical trials and observational studies. Despite many studies finding an independent association between blood urate levels and risk of incident CMR events, Mendelian randomization studies have largely found that serum urate is not causal for CMR end points or intermediate risk factors or outcomes (such as kidney function, adiposity, metabolic syndrome, glycaemic traits or blood lipid concentrations). Although limited, randomized controlled trials to date in adults without gout support this conclusion. If imaging studies suggesting that monosodium urate crystals are deposited in coronary plaques in patients with gout are confirmed, it is possible that these crystals might have a role in the inflammatory pathogenesis of increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout; removing monosodium urate crystals or blocking the inflammatory pathway could reduce this excess risk. Accordingly, data for CMR outcomes with these urate-lowering or anti-inflammatory therapies in patients with gout are needed. In the meantime, highly pleiotropic CMR and urate-lowering benefits of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and key lifestyle measures could play an important role in comorbidity care, in conjunction with effective gout care based on target serum urate concentrations according to the latest guidelines.

Key points

-

Exacerbated by the ‘Western’ lifestyle and obesity epidemics, the frequency and burden of gout, a hyperuricaemic metabolic condition complicated by excess cardiometabolic-renal (CMR) comorbidities and sequelae, have risen worldwide for decades.

-

Many prospective studies have associated blood urate levels with the development of incident CMR events, but evidence from Mendelian randomization studies and randomized controlled trials does not support a causal effect for serum (soluble) urate.

-

In addition to activating inflammasome pathways and inducing gout flares in joints, monosodium urate crystals might also deposit in coronary plaques and have pro-inflammatory roles in the pathogenesis of excess cardiovascular risk associated with gout, analogous to cholesterol crystals.

-

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, with their highly pleiotropic CMR and urate-lowering benefits, are an attractive alternative or adjunct therapy for patients with gout, although more evidence of their effects in gout populations is needed.

-

The downstream effects of weight loss and lifestyle modification, including adherence to healthy cardiometabolic diets, should simultaneously reduce CMR risk and serum urate concentrations and the risk of incident gout.

-

Pharmacotherapy and diet and lifestyle recommendations for gout prevention and management can be guided by concurrent CMR comorbidities and shared decision-making that reflects patient preferences.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Choi, H. K., Ford, E. S., Li, C. & Curhan, G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 57, 109–115 (2007).

Choi, H. K. & Curhan, G. Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation 116, 894–900 (2007).

Krishnan, E., Svendsen, K., Neaton, J. D., Grandits, G. & Kuller, L. H. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 1104–1110 (2008).

Kuo, C. F., Grainge, M. J., Mallen, C., Zhang, W. & Doherty, M. Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 661–667 (2015).

Rai, S. K. et al. Rising incidence and prevalence of gout in the Canadian general population. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 292–294 (2015).

Arromdee, E., Michet, C. J., Crowson, C. S., O’Fallon, W. M. & Gabriel, S. E. Epidemiology of gout: is the incidence rising? J. Rheumatol. 29, 2403–2406 (2002).

Elfishawi, M. M. et al. The rising incidence of gout and the increasing burden of comorbidities: a population-based study over 20 Years. J. Rheumatol. 45, 574–579 (2018).

Klemp, P., Stansfield, S. A., Castle, B. & Robertson, M. C. Gout is on the increase in New Zealand. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 56, 22–26 (1997).

Miao, Z. et al. Dietary and lifestyle changes associated with high prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in the Shandong coastal cities of Eastern China. J. Rheumatol. 35, 1859–1864 (2008).

Cassim, B., Mody, G. M., Deenadayalu, V. K. & Hammond, M. G. Gout in black South Africans: a clinical and genetic study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 53, 759–762 (1994).

Xia, Y. et al. Global, regional and national burden of gout, 19902017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study. Rheumatology 59, 1529–1538 (2020).

Safiri, S. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and years lived with disability due to gout and its attributable risk factors for 195 countries and territories 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72, 1916–1927 (2020).

Fam, A. G. Gout, diet, and the insulin resistance syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 29, 1350–1355 (2002).

Choi, H. K., Mount, D. B. & Reginato, A. M. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann. Intern. Med. 143, 499–516 (2005).

Zhu, Y., Pandya, B. J. & Choi, H. K. Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007–2008. Am. J. Med. 125, 679–687 e671 (2012).

Sandoval-Plata, G., Nakafero, G., Chakravorty, M., Morgan, K. & Abhishek, A. Association between serum urate, gout and comorbidities: a case-control study using data from the UK biobank. Rheumatology 60, 3243–3251 (2021).

Landgren, A. J., Dehlin, M., Jacobsson, L., Bergsten, U. & Klingberg, E. Cardiovascular risk factors in gout, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional survey of patients in Western Sweden. RMD Open 7, e001568 (2021).

England, B. et al. Multimorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and osteoarthritis within the rheumatology informatics system for effectiveness (RISE) registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 72, 111 (2020).

Elfishawi, M. M. et al. Changes in the presentation of incident gout and the risk of subsequent flares: a population-based study over 20 years. J. Rheumatol. 47, 613–618 (2020).

Fisher, M. C., Rai, S. K., Lu, N., Zhang, Y. & Choi, H. K. The unclosing premature mortality gap in gout: a general population-based study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1289–1294 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Improved survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 408–413 (2017).

Richette, P. et al. Improving cardiovascular and renal outcomes in gout: what should we target? Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 654–661 (2014).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 62, 170–180 (2010).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Hyperuricemia and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 61, 885–892 (2009).

Grayson, P. C., Kim, S. Y., LaValley, M. & Choi, H. K. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 63, 102–110 (2011).

Abbott, R. D., Brand, F. N., Kannel, W. B. & Castelli, W. P. Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 41, 237–242 (1988).

Krishnan, E., Baker, J. F., Furst, D. E. & Schumacher, H. R. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2688–2696 (2006).

Baker, J. F., Schumacher, H. R. & Krishnan, E. Serum uric acid level and risk for peripheral arterial disease: analysis of data from the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Angiology 58, 450–457 (2007).

Choi, H. K., De Vera, M. A. & Krishnan, E. Gout and the risk of type 2 diabetes among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile. Rheumatology 47, 1567–1570 (2008).

Rho, Y. H. et al. Independent impact of gout on the risk of diabetes mellitus among women and men: a population-based, BMI-matched cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 91–95 (2016).

Roughley, M. et al. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with gout and the impact of urate lowering therapy: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 20, 243 (2018).

Kuo, C. F., Grainge, M. J., Mallen, C., Zhang, W. & Doherty, M. Comorbidities in patients with gout prior to and following diagnosis: case-control study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 210–217 (2016).

De Vera, M. A., Rahman, M. M., Bhole, V., Kopec, J. A. & Choi, H. K. Independent impact of gout on the risk of acute myocardial infarction among elderly women: a population-based study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1162–1164 (2010).

Krishnan, E., Pandya, B. J., Chung, L., Hariri, A. & Dabbous, O. Hyperuricemia in young adults and risk of insulin resistance, prediabetes, and diabetes: a 15-year follow-up study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 176, 108–116 (2012).

Choi, H. K., Atkinson, K., Karlson, E. W. & Curhan, G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 742–748 (2005).

Choi, H. K. et al. Population impact attributable to modifiable risk factors for hyperuricemia. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72, 157–165 (2020).

McCormick, N. et al. Estimation of primary prevention of gout in men through modification of obesity and other key lifestyle factors. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2027421 (2020).

Choi, H. K. & Curhan, G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 336, 309–312 (2008).

Choi, H. K., Willett, W. & Curhan, G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA 304, 2270–2278 (2010).

Gao, X. et al. Intake of added sugar and sugar-sweetened drink and serum uric acid concentration in US men and women. Hypertension 50, 306–312 (2007).

Kim, S. C. et al. Cardiovascular risks of probenecid versus allopurinol in older patients with gout. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 994–1004 (2018).

Hay, C. A., Prior, J. A., Belcher, J., Mallen, C. D. & Roddy, E. Mortality in patients with gout treated with allopurinol: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 73, 1049–1054 (2021).

Weisman, A. et al. Allopurinol and renal outcomes in adults with and without type 2 diabetes: a retrospective, population-based cohort study and propensity score analysis. Can. J. Diabetes 45, 641–649.e4 (2021).

Suissa, S., Suissa, K. & Hudson, M. Effectiveness of allopurinol on reducing mortality: time-related biases in observational studies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 1749–1757 (2021).

Suissa, S., Suissa, K. & Hudson, M. Allopurinol and cardiovascular events: time-related biases in observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24713 (2021).

Pierce, B. L. & Burgess, S. Efficient design for Mendelian randomization studies: subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators. Am. J. Epidemiol. 178, 1177–1184 (2013).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 362, k601 (2018).

Tin, A. et al. Target genes, variants, tissues and transcriptional pathways influencing human serum urate levels. Nat. Genet. 51, 1459–1474 (2019).

Choi, J. W., McCormick, N., Marozoff, S., De Vera, M. & Choi, H. K. The impact of genetically determined serum urate levels on the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies [abstract]. Ann. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.6191 (2020).

Sumpter, N. A., Saag, K. G., Reynolds, R. J. & Merriman, T. R. Comorbidities in gout and hyperuricemia: causality or epiphenomena? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 32, 126–133 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Serum uric acid levels and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of evidence from observational studies, randomised controlled trials, and Mendelian randomisation studies. BMJ 357, j2376 (2017).

Keerman, M. et al. Mendelian randomization study of serum uric acid levels and diabetes risk: evidence from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 8, e000834 (2020).

Efstathiadou, A., Gill, D., McGrane, F., Quinn, T. & Dawson, J. Genetically determined uric acid and the risk of cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases: a Mendelian randomization study of outcomes investigated in randomized trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012738 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Multiple genetic loci influence serum urate levels and their relationship with gout and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 523–530 (2010).

Li, X. et al. MR-PheWAS: exploring the causal effect of SUA level on multiple disease outcomes by using genetic instruments in UK Biobank. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 1039–1047 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Genetically determined serum urate levels and cardiovascular and other diseases in UK Biobank cohort: a phenome-wide mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 16, e1002937 (2019).

Si, S. et al. Causal pathways from body components and regional fat to extensive metabolic phenotypes: a Mendelian randomization study. Obesity 28, 1536–1549 (2020).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: Mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 347, f4262 (2013).

Wang, L., Zhang, T., Liu, Y., Tang, F. & Xue, F. Association of serum uric acid with metabolic syndrome and its components: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 6238693 (2020).

Parsa, A. et al. Genotype-based changes in serum uric acid affect blood pressure. Kidney Int. 81, 502–507 (2012).

Gill, D. et al. Urate, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease: evidence from Mendelian randomization and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Hypertension 77, 383–392 (2021).

Biradar, M. I., Chiang, K. M., Yang, H. C., Huang, Y. T. & Pan, W. H. The causal role of elevated uric acid and waist circumference on the risk of metabolic syndrome components. Int. J. Obes. 44, 865–874 (2020).

Mallamaci, F. et al. A polymorphism in the major gene regulating serum uric acid associates with clinic SBP and the white-coat effect in a family-based study. J. Hypertens. 32, 1621–1628 (2014). discussion 1628.

Sedaghat, S. et al. Association of uric acid genetic risk score with blood pressure: the Rotterdam study. Hypertension 64, 1061–1066 (2014).

Lyngdoh, T. et al. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS One 7, e39321 (2012).

Rasheed, H., Hughes, K., Flynn, T. J. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for a causal role of serum urate in increasing serum triglyceride levels. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 7, 830–837 (2014).

Yu, X., Wang, T., Huang, S. & Zeng, P. Evaluation of the causal effects of blood lipid levels on gout with summary level GWAS data: two-sample Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 465–473 (2021).

McCormick, N. et al. Assessing the causal relationships between insulin resistance and hyperuricemia and gout using bidirectional Mendelian randomization. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 2096–2104 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 840–860 (2021).

Ter Maaten, J. C. et al. Renal handling of urate and sodium during acute physiological hyperinsulinaemia in healthy subjects. Clin. Sci. 92, 51–58 (1997).

Muscelli, E. et al. Effect of insulin on renal sodium and uric acid handling in essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 9, 746–752 (1996).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension 41, 1183–1190 (2003).

Mene, P. & Punzo, G. Uric acid: bystander or culprit in hypertension and progressive renal disease? J. Hypertens. 26, 2085–2092 (2008).

Khosla, U. M. et al. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 67, 1739–1742 (2005).

Farquharson, C. A., Butler, R., Hill, A., Belch, J. J. & Struthers, A. D. Allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Circulation 106, 221–226 (2002).

Doehner, W. et al. Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibition with allopurinol on endothelial function and peripheral blood flow in hyperuricemic patients with chronic heart failure: results from 2 placebo-controlled studies. Circulation 105, 2619–2624 (2002).

Rao, G. N., Corson, M. A. & Berk, B. C. Uric acid stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by increasing platelet-derived growth factor A-chain expression. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 8604–8608 (1991).

Mazzali, M. et al. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282, F991–F997 (2002).

Toma, I., Kan, J., Meer, E. & Pet-Peterdi, J. Uric acid triggers renin release via a macula densa-dependent pathway. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 156A (2007).

Mazzali, M. et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension 38, 1101–1106 (2001).

Feig, D. I., Soletsky, B. & Johnson, R. J. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA 300, 924–932 (2008).

Soletsky, B. & Feig, D. I. Uric acid reduction rectifies prehypertension in obese adolescents. Hypertension 60, 1148–1156 (2012).

McMullan, C. J., Borgi, L., Fisher, N., Curhan, G. & Forman, J. Effect of uric acid lowering on renin-angiotensin-system activation and ambulatory BP: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, 807–816 (2017).

Gaffo, A. L. et al. Effect of serum urate lowering with allopurinol on blood pressure in young adults: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 1514–1522 (2021).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Essential hypertension, progressive renal disease, and uric acid: a pathogenetic link? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 1909–1919 (2005).

Doria, A. et al. Serum urate lowering with allopurinol and kidney function in type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2493–2503 (2020).

Badve, S. V. et al. Effects of allopurinol on the progression of chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2504–2513 (2020).

George, J., Carr, E., Davies, J., Belch, J. J. & Struthers, A. High-dose allopurinol improves endothelial function by profoundly reducing vascular oxidative stress and not by lowering uric acid. Circulation 114, 2508–2516 (2006).

Noman, A., Ang, D. S., Ogston, S., Lang, C. C. & Struthers, A. D. Effect of high-dose allopurinol on exercise in patients with chronic stable angina: a randomised, placebo controlled crossover trial. Lancet 375, 2161–2167 (2010).

Berry, C. E. & Hare, J. M. Xanthine oxidoreductase and cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. J. Physiol. 555, 589–606 (2004).

Rajagopalan, S., Meng, X. P., Ramasamy, S., Harrison, D. G. & Galis, Z. S. Reactive oxygen species produced by macrophage-derived foam cells regulate the activity of vascular matrix metalloproteinases in vitro. Implications for atherosclerotic plaque stability. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 2572–2579 (1996).

Takimoto, E. & Kass, D. A. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Hypertension 49, 241–248 (2007).

Rajendra, N. S. et al. Mechanistic insights into the therapeutic use of high-dose allopurinol in angina pectoris. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 820–828 (2011).

Khatib, S. Y., Farah, H. & El-Migdadi, F. Allopurinol enhances adenine nucleotide levels and improves myocardial function in isolated hypoxic rat heart. Biochemistry 66, 328–333 (2001).

Hirsch, G. A., Bottomley, P. A., Gerstenblith, G. & Weiss, R. G. Allopurinol acutely increases adenosine triphosphate energy delivery in failing human hearts. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59, 802–808 (2012).

Mackenzie, I. S. et al. Multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded end point trial of the efficacy of allopurinol therapy in improving cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ischaemic heart disease: protocol of the ALL-HEART study. BMJ Open 6, e013774 (2016).

Khunti, K. SGLT2 inhibitors in people with and without T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 75–76 (2021).

Bailey, C. J. Uric acid and the cardio-renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 21, 1291–1298 (2019).

Fralick, M., Chen, S. K., Patorno, E. & Kim, S. C. Assessing the risk for gout with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, 186–194 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors on serum uric acid level: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 20, 458–462 (2018).

Packer, M. et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1413–1424 (2020).

McMurray, J. J. V. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1995–2008 (2019).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1436–1446 (2020).

Reyes, A. J. Cardiovascular drugs and serum uric acid. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 17, 397–414 (2003).

No authors listed. Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and propranolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Report of medical research council working party on mild to moderate hypertension. Lancet 2, 539–543 (1981).

Burnier, M., Waeber, B. & Brunner, H. R. Clinical pharmacology of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan potassium in healthy subjects. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 13, S23–S28 (1995).

Burnier, M., Roch-Ramel, F. & Brunner, H. R. Renal effects of angiotensin II receptor blockade in normotensive subjects. Kidney Int. 49, 1787–1790 (1996).

Wurzner, G. et al. Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J. Hypertens. 19, 1855–1860 (2001).

Minghelli, G., Seydoux, C., Goy, J. J. & Burnier, M. Uricosuric effect of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan in heart transplant recipients. Transplantation 66, 268–271 (1998).

Hamada, T. et al. Effect of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan on uric acid and oxypurine metabolism in healthy subjects. Intern. Med. 41, 793–797 (2002).

Hoieggen, A. et al. The impact of serum uric acid on cardiovascular outcomes in the LIFE study. Kidney Int. 65, 1041–1049 (2004).

Alderman, M. & Aiyer, K. J. Uric acid: role in cardiovascular disease and effects of losartan. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 20, 369–379 (2004).

Choi, H. K., Soriano, L. C., Zhang, Y. & Rodriguez, L. A. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ 344, d8190 (2012).

Bruderer, S., Bodmer, M., Jick, S. S. & Meier, C. R. Use of diuretics and risk of incident gout: a population-based case-control study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 185–196 (2014).

Waldman, B. et al. Effect of fenofibrate on uric acid and gout in type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the randomised, controlled FIELD study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 310–318 (2018).

Martinon, F., Petrilli, V., Mayor, A., Tardivel, A. & Tschopp, J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440, 237–241 (2006).

Dalbeth, N. et al. Gout. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 69 (2019).

So, A. K. & Martinon, F. Inflammation in gout: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 639–647 (2017).

Strandberg, T. E. & Kovanen, P. T. Coronary artery disease: ‘gout’ in the artery? Eur. Heart J. 42, 2761–2764 (2021).

Grebe, A., Hoss, F. & Latz, E. NLRP3 inflammasome and the IL-1 pathway in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 122, 1722–1740 (2018).

Klauser, A. S. et al. Dual-energy computed tomography detection of cardiovascular monosodium urate deposits in patients with gout. JAMA Cardiol. 4, 1019–1028 (2019).

Barazani, S. H. et al. Quantification of uric acid in vasculature of patients with gout using dual-energy computed tomography. World J. Radiol. 12, 184–194 (2020).

Feuchtner, G. M. et al. Monosodium urate crystal deposition in coronary artery plaque by 128-slice dual-energy computed tomography: an ex vivo phantom and in vivo study. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 45, 856–862 (2021).

Becce, F., Ghoshhajra, B. & Choi, H. K. Identification of cardiovascular monosodium urate crystal deposition in patients with gout using dual-energy computed tomography. JAMA Cardiol. 5, 486 (2020).

Nishimiya, K. et al. A novel approach for uric acid crystal detection in human coronary arteries with polarization-sensitive micro-OCT [abstract]. Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy565.P2772 (2018).

Oh, W. Y. et al. High-speed polarization sensitive optical frequency domain imaging with frequency multiplexing. Opt. Express 16, 1096–1103 (2008).

Ridker, P. M. et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1119–1131 (2017).

Bardin, T. et al. A cross-sectional study of 502 patients found a diffuse hyperechoic kidney medulla pattern in patients with severe gout. Kidney Int. 99, 218–226 (2021).

Pascual, E. Persistence of monosodium urate crystals and low-grade inflammation in the synovial fluid of patients with untreated gout. Arthritis Rheum. 34, 141–145 (1991).

White, W. B. et al. Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1200–1210 (2018).

Choi, H., Neogi, T., Stamp, L., Dalbeth, N. & Terkeltaub, R. New perspectives in rheumatology: implications of the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat and allopurinol in patients with gout and cardiovascular morbidities trial and the associated food and drug administration public safety alert. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 1702–1709 (2018).

FDA. FDA adds Boxed Warning for increased risk of death with gout medicine Uloric (febuxostat). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-increased-risk-death-gout-medicine-uloric-febuxostat (2019).

Mackenzie, I. S. et al. Long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (FAST): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 396, 1745–1757 (2020).

Choi, H. K., Neogi, T., Stamp, L. K., Terkeltaub, R. & Dalbeth, N. Reassessing the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat: implications of the febuxostat versus allopurinol streamlined trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 721–724 (2021).

Bardin, T. & Richette, P. FAST: new look at the febuxostat safety profile. Lancet 396, 1704–1705 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk in older patients with gout initiating febuxostat versus allopurinol: population-based cohort study. Circulation 138, 1116–1126 (2018).

Kang, E. H. & Kim, S. C. Cardiovascular safety of urate lowering therapies. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 21, 48 (2019).

Doherty, M. et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 392, 1403–1412 (2018).

Becker, M. A. et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2450–2461 (2005).

Tong, D. C. et al. Colchicine in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the Australian COPS randomized clinical trial. Circulation 142, 1890–1900 (2020).

Tardif, J. C. et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2497–2505 (2019).

Nidorf, S. M. et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1838–1847 (2020).

Nidorf, S. M., Eikelboom, J. W., Budgeon, C. A. & Thompson, P. L. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 404–410 (2013).

McGill, N. W. Gout and other crystal-associated arthropathies. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 14, 445–460 (2000).

Emmerson, B. Hyperlipidaemia in hyperuricaemia and gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 57, 509–510 (1998).

Vuorinen-Markkola, H. & Yki-Jarvinen, H. Hyperuricemia and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 78, 25–29 (1994).

Lee, J., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P. S., Landsberg, L. & Weiss, S. T. Uric acid and coronary heart disease risk: evidence for a role of uric acid in the obesity-insulin resistance syndrome. The normative aging study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 142, 288–294 (1995).

Puig, J. G. & Ruilope, L. M. Uric acid as a cardiovascular risk factor in arterial hypertension. J. Hypertens. 17, 869–872 (1999).

Gepner, Y. et al. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools: CENTRAL magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial. Circulation 137, 1143–1157 (2018).

Duncan, G. E. et al. Exercise training, without weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity and postheparin plasma lipase activity in previously sedentary adults. Diabetes Care 26, 557–562 (2003).

Tsaban, G. et al. The effect of green Mediterranean diet on cardiometabolic risk; a randomised controlled trial. Heart https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317802 (2020).

Yaskolka Meir, A. et al. Effect of green-Mediterranean diet on intrahepatic fat: the DIRECT PLUS randomised controlled trial. Gut 70, 2085–2095 (2021).

Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis — no longer a theory. Clin. Chem. 67, 131–142 (2021).

Arts, E. E. et al. Performance of four current risk algorithms in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 668–674 (2015).

Arts, E. E. et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: performance of original and adapted SCORE algorithms. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 674–680 (2016).

Crowson, C. S., Matteson, E. L., Roger, V. L., Therneau, T. M. & Gabriel, S. E. Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Cardiol. 110, 420–424 (2012).

Kawai, V. K. et al. The ability of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cardiovascular risk score to identify rheumatoid arthritis patients with high coronary artery calcification scores. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 381–385 (2015).

Andres, M. et al. Cardiovascular risk of patients with gout seen at rheumatology clinics following a structured assessment. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1263–1268 (2017).

Arnett, D. K. et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, e177–e232 (2019).

Greenland, P., Yano, Y. & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk in elderly populations — reply. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 180–181 (2018).

Erbel, R. et al. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56, 1397–1406 (2010).

Polonsky, T. S. et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA 303, 1610–1616 (2010).

Hoffmann, U. et al. Cardiovascular event prediction and risk reclassification by coronary, aortic, and valvular calcification in the Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5, e003144 (2016).

Gepner, A. D. et al. Comparison of carotid plaque score and coronary artery calcium score for predicting cardiovascular disease events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005179 (2017).

Gepner, A. D. et al. Comparison of coronary artery calcium presence, carotid plaque presence, and carotid intima-media thickness for cardiovascular disease prediction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 8, e002262 (2015).

Choi, J. W., Ford, E. S., Gao, X. & Choi, H. K. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 59, 109–116 (2008).

Dessein, P. H., Shipton, E. A., Stanwix, A. E., Joffe, B. I. & Ramokgadi, J. Beneficial effects of weight loss associated with moderate calorie/carbohydrate restriction, and increased proportional intake of protein and unsaturated fat on serum urate and lipoprotein levels in gout: a pilot study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, 539–543 (2000).

Guasch-Ferre, M. et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of hyperuricemia in elderly participants at high cardiovascular risk. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 68, 1263–1270 (2013).

Yokose, C. et al. Effects of low-fat, Mediterranean, or low-carbohydrate weight loss diets on serum urate and cardiometabolic risk factors: a secondary analysis of the dietary intervention randomized controlled trial (DIRECT). Diabetes Care 43, 2812–2820 (2020).

Yokose, C. et al. Adherence to 2020–2025 dietary guidelines for Americans and the risk of new onset female gout. JAMA Int. Med. In press (2021).

Juraschek, S. P., Gelber, A. C., Choi, H. K., Appel, L. J. & Miller, E. R. 3rd Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and sodium intake on serum uric acid. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 3002–3009 (2016).

Juraschek, S. P. et al. Effects of dietary patterns on serum urate: results from a randomized trial of the effects of diet on hypertension. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 1014–1020 (2021).

Rai, S. K. et al. The dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet, Western diet, and risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 357, j1794 (2017).

Richette, P., Clerson, P., Perissin, L., Flipo, R. M. & Bardin, T. Revisiting comorbidities in gout: a cluster analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 142–147 (2015).

Yokose, C., Lu, L., Chen-Xu, M., Zhang, Y. & Choi, H. K. Comorbidity patterns in gout using the US general population: cluster analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, A1294 (2019).

Bevis, M., Blagojevic-Bucknall, M., Mallen, C., Hider, S. & Roddy, E. Comorbidity clusters in people with gout: an observational cohort study with linked medical record review. Rheumatology 57, 1358–1363 (2018).

Bajpai, R. et al. Onset of comorbidities and flare patterns within pre-existing morbidity clusters in people with gout: 5-year primary care cohort study. Rheumatology https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab283 (2021).

Appel, L. J. et al. Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA 294, 2455–2464 (2005).

Shai, I. et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 229–241 (2008).

Chiuve, S. E. et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J. Nutr. 142, 1009–1018 (2012).

Scheen, A. J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16, 556–577 (2020).

White, J. et al. Plasma urate concentration and risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 327–336 (2016).

Keenan, T. et al. Causal assessment of serum urate levels in cardiometabolic diseases through a Mendelian randomization study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 407–416 (2016).

Kleber, M. E. et al. Uric acid and cardiovascular events: a Mendelian randomization study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 2831–2838 (2015).

Stark, K. et al. Common polymorphisms influencing serum uric acid levels contribute to susceptibility to gout, but not to coronary artery disease. PLoS One 4, e7729 (2009).

Han, X. et al. Associations of the uric acid related genetic variants in SLC2A9 and ABCG2 loci with coronary heart disease risk. BMC Genet. 16, 4 (2015).

Chiang, K. M. et al. Is hyperuricemia, an early-onset metabolic disorder, causally associated with cardiovascular disease events in Han Chinese? J. Clin. Med. 8, 1202 (2019).

Macias-Kauffer, L. R. et al. Genetic contributors to serum uric acid levels in Mexicans and their effect on premature coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 279, 168–173 (2019).

Jordan, D. M. et al. No causal effects of serum urate levels on the risk of chronic kidney disease: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 16, e1002725 (2019).

Hughes, K., Flynn, T., de Zoysa, J., Dalbeth, N. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization analysis associates increased serum urate, due to genetic variation in uric acid transporters, with improved renal function. Kidney Int. 85, 344–351 (2014).

Greenberg, K. I. et al. Plasma urate and risk of a hospital stay with AKI: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 776–783 (2015).

Zhu, J. et al. Genetic predisposition to type 2 diabetes and insulin levels is positively associated with serum urate levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, e2547–e2556 (2021).

Pfister, R. et al. No evidence for a causal link between uric acid and type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomisation approach. Diabetologia 54, 2561–2569 (2011).

Sluijs, I. et al. A Mendelian randomization study of circulating uric acid and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64, 3028–3036 (2015).

McKeigue, P. M. et al. Bayesian methods for instrumental variable analysis with genetic instruments (‘Mendelian randomization’): example with urate transporter SLC2A9 as an instrumental variable for effect of urate levels on metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39, 907–918 (2010).

Dai, X. et al. Association between serum uric acid and the metabolic syndrome among a middle- and old-age Chinese population. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 28, 669–676 (2013).

Hu, X. et al. Association between plasma uric acid and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 171, 108542 (2021).

Larsson, S. C., Burgess, S. & Michaelsson, K. Genetic association between adiposity and gout: a Mendelian randomization study. Rheumatology 57, 2145–2148 (2018).

O’Dell, J. et al. Urate lowering therapy in the treatment of gout. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind comparison of allopurinol and febuxostat using a treat-to-target strategy [Abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 73, 3968–3970 (2021).

Qaseem, A., Harris, R. P. & Forciea, M. A. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166, 58–68 (2017).

Khanna, D. et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 64, 1431–1446 (2012).

Liu, L. et al. Imaging the subcellular structure of human coronary atherosclerosis using micro-optical coherence tomography. Nat. Med. 17, 1010–1014 (2011).

Bardin, T. et al. Renal medulla in severe gout: typical findings on ultrasonography and dual-energy CT study in two patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, 433–434 (2019).

Kottgen, A. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat. Genet. 45, 145–154 (2013).

Menni, C., Zierer, J., Valdes, A. M. & Spector, T. D. Mixing omics: combining genetics and metabolomics to study rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 174–181 (2017).

Colaco, K. et al. Targeted metabolomic profiling and prediction of cardiovascular events: a prospective study of patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1429–1435 (2021).

Acknowledgements

H.K.C. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-AR065944 and P50-AR060772. N.M. is supported by a Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. C.Y. is supported by a Scientist Development Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article. H.K.C. contributed substantially to discussion of the content. All authors wrote the article and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.K.C. reports research support from Ironwood and Horizon, and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa and Vaxart. N.M. and C.Y. declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Rheumatology thanks M. Dehlin, F. Liote and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Glossary

- Instrumental variables

-

Variables (for example, single or multiple genetic variants) that function as a proxy for the exposure of interest and must be associated with the exposure but cannot be independently associated with the outcome of interest (that is, outside its association with the exposure itself).

- Non-pleiotropic variants

-

A genetic variant associated only with the exposure of interest (for example, serum urate levels) and not directly associated with the outcome of interest (for example, fasting insulin levels) or other traits that could be causal for the outcome of interest through a different pathway (for example, triglycerides).

- Horizontal pleiotropy

-

When genetic variants can affect the outcome of interest through more than one biological pathway, including those that are independent of the exposure of interest.

- Pleiotropic variants

-

Genetic variants associated with the exposure of interest (for example, serum urate levels) but also directly associated with additional traits (for example, triglyceride levels) that could affect the outcome of interest (for example, fasting insulin levels) independently of the main exposure.

- Beam-hardening artefacts

-

Phenomena that occur when lower energy photons are selectively attenuated as they pass through a dense object.

- Partial volume effects

-

Phenomena that occur when tissues of widely different absorption are included in the same CT voxel, producing a beam attenuation that is proportional to the average value of the tissues within the voxel.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, H.K., McCormick, N. & Yokose, C. Excess comorbidities in gout: the causal paradigm and pleiotropic approaches to care. Nat Rev Rheumatol 18, 97–111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-021-00725-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-021-00725-9

This article is cited by

-

The clinical benefits of sodium–glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors in people with gout

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2024)

-

Pipeline Therapies for Gout

Current Rheumatology Reports (2024)

-

Electroacupuncture improves gout arthritis pain via attenuating ROS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome overactivation

Chinese Medicine (2023)

-

Association between periodontitis and uric acid levels in blood and oral fluids: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Empfehlungen der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Rheumatologie und Rehabilitation zu Ernährung und Lebensstil bei Gicht und Hyperurikämie – Update 2022

Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie (2023)