Abstract

Osteomyelitis remains one of the greatest risks in orthopaedic surgery. Although many organisms are linked to skeletal infections, Staphylococcus aureus remains the most prevalent and devastating causative pathogen. Important discoveries have uncovered novel mechanisms of S. aureus pathogenesis and persistence within bone tissue, including implant-associated biofilms, abscesses and invasion of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network. However, little clinical progress has been made in the prevention and eradication of skeletal infection as treatment algorithms and outcomes have only incrementally changed over the past half century. In this Review, we discuss the mechanisms of persistence and immune evasion in S. aureus infection of the skeletal system as well as features of other osteomyelitis-causing pathogens in implant-associated and native bone infections. We also describe how the host fails to eradicate bacterial bone infections, and how this new information may lead to the development of novel interventions. Finally, we discuss the clinical management of skeletal infection, including osteomyelitis classification and strategies to treat skeletal infections with emerging technologies that could translate to the clinic in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is an infection of bone that can result from contiguous spread from surrounding tissue, direct bone trauma due to surgery or injury, or haematogenous spread from systemic bacteraemia. It remains a significant health-care burden with a prevalence of ~22 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States, and its incidence has been rising over time, especially in the elderly and individuals with diabetes1. Although it is a heterogeneous disease, subset classifications include implant-associated osteomyelitis (including peri-prosthetic joint infection (PJI) and instrumented spinal infections), fracture-related infection, acute haematogenous osteomyelitis, diabetic foot infection, septic arthritis and native spinal osteomyelitis.

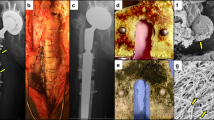

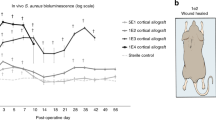

Crucial to expanding our understanding of osteomyelitis and advancing treatment algorithms has been the application of animal models, which illustrate the interaction between the pathogen and cells of both the immune and skeletal systems in a manner that in vitro models cannot yet replicate. Animal models are available to study virtually all aspects of skeletal infection, and typically involve inoculation of bacteria at the time of implant placement (Fig. 1). They can vary in complexity from simple models where metal implants are placed under the skin (for example, tissue cage2) or into cortical bone (for example, metal wire3) versus more complex models that mimic functional orthopaedic devices4. Additionally, approaches have been developed to induce non-implant infections by haematogenous inoculation into the tail vein5, direct inoculation into vertebral bodies or intervertebral discs6 to induce vertebral osteomyelitis, or inoculation into the foot pad of diabetic obese rodents to induce diabetic foot infection7.

Animal studies have been instrumental in some of the most important discoveries that have advanced our understanding of musculoskeletal infection. In broad terms, these models may be classified into implant-related or non-implant-related models. Many of the implant-related models utilize simplified biomaterials to represent the orthopaedic device (grey) that may be placed in the subcutaneous space (for example, tissue cages or discs) or within the bone (for example, Kirschner wires or pins) and offer simplicity and a relatively low risk profile. Certain studies may require use of functional devices whereby the implant placed in the animal serves to fix a fracture or replace a joint (green) and these may be particularly useful where bone healing, implant biomechanics or regulatory approval is the goal. Finally, several models have been developed that do not fit within either category as they may model specific disease entities (purple), such as haematogenous inoculation, leading to osteomyelitis, tendon infection, vertebral osteomyelitis or the use of comorbid mice such as diabetic obese mice.

As disease pathogenesis differs across different infection classes, so does microbial aetiology. Many different microorganisms have been implicated in skeletal infection, and the most common, along with their incidence and tropism, are shown in Table 1. In general, Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus lugdunensis, are responsible for up to two-thirds of all skeletal infections, with S. aureus being the most prevalent single pathogen. Additionally, antimicrobial resistance remains a challenge in osteomyelitis treatment with up to 50% of cases of S. aureus osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains8. Other less commonly identified pathogens include Enterococcus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Cutibacterium acnes (Table 1). Most cases of osteomyelitis are monomicrobial; however, polymicrobial infections represent an important subset of cases in many different types of osteomyelitis, including trauma-related or fracture-related infections and infections of the foot or ankle.

In this Review, we summarize recently described mechanisms of S. aureus osteomyelitis pathogenesis, including intracellular infection, staphylococcal abscess communities (SACs) and invasion of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network (OLCN). We describe emerging mechanisms and pathophysiology of skeletal infections caused by other pathogens, including CoNS, C. acnes and Streptococcus agalactiae. Furthermore, we discuss various host immune evasion strategies employed by these pathogens during the establishment of osteomyelitis and introduce the theory of susceptible versus protective immune proteomes in the context of skeletal infections. Finally, we summarize current clinical standards of care and controversies for the treatment of skeletal infections, challenges in diagnosing the causative pathogens, and emerging strategies in prevention and treatment.

S. aureus in skeletal infections

S. aureus is the most prevalent and most destructive pathogen in skeletal infections. From asymptomatic skin colonization to life-threatening disease, this Gram-positive bacterium has evolved to infect nearly every human tissue type. S. aureus is specifically pathogenic in skeletal infections because of its unique ability to invade, colonize and thrive within bone. Key mechanisms for S. aureus persistence in skeletal infections are outlined in Fig. 2.

Staphylococcus aureus employs a variety of pathogenic mechanisms during skeletal infection. Intracellular infection of osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes has been investigated as a possible source of long-term S. aureus persistence during osteomyelitis and ‘Trojan horse’ macrophages have been shown to cause bacterial dissemination and multiorgan failure. S. aureus invasion of the osteocyte-lacuno canalicular network (OLCN), most commonly within a sequestrum, permits evasion of host immune cells during osteomyelitis and requires S. aureus deformation to invade canaliculi of bone. S. aureus biofilms formed on implant surfaces and necrotic bone confer resistance to immune cell attack and antibiotic therapy through diffusion limitations and metabolic diversity of S. aureus cells. Lastly, staphylococcal abscess communities can form within the medullary cavity of long bones and in associated soft tissue. Gram-positive S. aureus cells are found at the centre of an abscess surrounded by a fibrous pseudocapsule encasing bacterial cells, followed by layers of dead and live immune cells. Note the formation of a necrotic bone fragment (sequestrum) and new bone formation (involucrum) during prolonged infection. CHIPS, chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus; ClfA/B, clumping factor A/B; CoA, coagulase; Eap, extracellular adherence protein; eDNA, extracellular DNA; Ess, ESAT-6 secretion system; FnBPA/B, fibronectin-binding protein A/B; Hla, α-haemolysin; MSCRAMMs, microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules; PBP3/4, penicillin-binding protein 3/4; PIA, polysaccharide intercellular adhesin; PSM, phenol-soluble modulins; PVL, Panton–Valentine leukocidin; SCIN, staphylococcal complement inhibitor; SCVs, small colony variants; TSST1, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1; vWbp, von Willebrand factor-binding protein.

Intracellular infection

The role of intracellular infection during osteomyelitis remains an active topic of research. Many groups have proposed long-term intracellular infection of bone cells by S. aureus as a mechanism for infection persistence and recurrence following long periods of dormancy, which is frequently observed in clinical cases of S. aureus osteomyelitis9.

S. aureus intracellular persistence has been described in a variety of cell types, including macrophages10, keratinocytes11, epithelial cells12 and endothelial cells13. Specifically, intracellular infection of macrophages, oftentimes called ‘Trojan horse’ macrophages, can facilitate bacterial dissemination through the body and enrichment for small colony variants (SCVs)10. S. aureus invasion of non-professional phagocytes has been described as host-mediated uptake where fibronectin bridges S. aureus cell-surface fibronectin-binding proteins A or B (FnBPA or FnBPB) with host cell α5β1 integrins, triggering cytoskeletal reorganization and bacterial cell uptake13,14.

In the setting of bone, in vitro studies have shown S. aureus invasion and survival within osteoblasts15,16,17, osteoclasts18,19 and osteocytes20, and clinical case studies have described intracellular colonization of fibroblasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes from chronically infected bone tissue21,22. Direct infection of bone cells is particularly pathogenic as it has been shown to induce the secretion of osteoclastogenic cytokines, contributing to pathological bone loss. Furthermore, some hypothesize that intracellularly infected osteoblasts that undergo differentiation or maturation into osteocytes could serve as a long-term and immune-privileged reservoir for bacterial colonization of bone23.

Owing to limited in vivo studies, it is unclear how long S. aureus can persist inside bone cells, and how many bone cells are typically colonized with S. aureus in an infected lesion. Therefore, further studies using in vivo models of osteomyelitis are required to elucidate the involvement of S. aureus intracellular colonization in osteomyelitis.

OLCN invasion

The recent discovery of S. aureus invasion of the OLCN of cortical bone during osteomyelitis may provide another explanation for long-term bacterial persistence and treatment failure in osteomyelitis. In contrast to the dogma that S. aureus is a non-motile cocci organism, recent studies in experimental models24 and clinical cases25 of osteomyelitis have revealed that S. aureus can invade and persist within the OLCN. Notably, S. aureus deforms to approximately half its native size to colonize the narrow confines of canaliculi, which are 100–600 nm in diameter26. S. aureus cell wall synthesis machinery and surface adhesins may enable invasion of the OLCN guided by durotaxis27 and haptotaxis28. To test this hypothesis, an in vitro model, called the µSiM-CA and designed to mimic canalicular invasion, was used to identify S. aureus genes required for canalicular invasion29. In vitro and in vivo studies identified pbp3 and pbp4 as crucial genes for sub-micron propagation and invasion of the OLCN30. pbp3 and pbp4 encode non-essential cell wall transpeptidases penicillin-binding proteins 3 and 4 (PBP3 and PBP4), which function in the final stages of cell wall synthesis31. This work suggests that inhibition of PBP3 and/or PBP4 may prevent S. aureus OLCN invasion, and their inhibitors could be used as adjuvants for antimicrobial treatment of S. aureus osteomyelitis.

Currently, it is unclear whether antibiotics readily diffuse into the OLCN of cortical bone at inhibitory concentrations. Murine studies have shown that the small molecule bromodeoxyuridine diffuses into infected canaliculi in vivo when added to the animal’s drinking water24. However, vancomycin treatment fails to eradicate MRSA within the OLCN of infected bone30, and gentamicin treatment induced cell wall thickening of S. aureus within canaliculi32. These results suggest that both parenteral and local high-dose antibiotics reach bacteria within the OLCN at sub-inhibitory concentrations, thereby inducing the tolerant or persistent phenotypes. Novel therapies designed to inhibit OLCN invasion may be an effective adjuvant in combination with other bactericidal agents to improve infection eradication and reduce bacterial persistence.

Biofilm formation

An important and well-studied mechanism for S. aureus pathogenesis in osteomyelitis is the formation of biofilms, which has been extensively reviewed33,34. S. aureus biofilms on necrotic bone and implant surfaces are particularly hard to eradicate because they limit antibiotic diffusion to bacterial cells, inhibit immune cell penetration and resist mechanical disruption. Furthermore, bacterial cells within a biofilm are metabolically diverse due to the gradients of nutrient and oxygen availability, thereby facilitating the selection of SCVs and persister cell populations.

The Agr quorum-sensing system is a key regulator of S. aureus biofilm formation. At low cell densities, S. aureus expresses microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) (for example, FnBPA, FnBPB, Cna and SpA), which initiate adhesion to an abiotic substrate35. Following adhesion, the bacterial cells continue to proliferate, and synthesize and secrete extracellular polymeric substances such as polysaccharide intercellular adhesion and extracellular DNA, involving the expression of the ica operon36. At high cell densities, autoinducing peptides reach a threshold concentration that activates the AgrC–AgrA two-component system37. The activation of the Agr system results in downregulation of MSCRAMMs and upregulation of phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) and secreted toxins (for example, α-haemolysin (Hla), Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST1)), which in turn triggers bacterial dispersal from the mature biofilm35.

Abscess formation

In addition to biofilms, S. aureus has the unique ability to chronically infect bone marrow and peri-implant soft tissue by forming robust SACs during osteomyelitis. The presence of SACs at the site of a bone infection is often used to diagnose and/or classify the stage of osteomyelitis38 as SACs can greatly increase the severity of infections by restricting blood flow to the area39. Although these bacterial lesions, also described as Brodie abscesses when found in bone tissue, have been studied for two centuries40, recent research has formally demonstrated their resistance to standard-of-care antibiotics and host immune responses41,42.

The formation of SACs represents an effective manipulation of the host response to prolonged S. aureus survival within soft tissues. SACs occur when bacteria exploit the host response to encase themselves in a protective barrier and persist for prolonged periods of time41. S. aureus first enables the formation of a protective fibrous pseudocapsule through the activity of coagulase (CoA) and von Willebrand factor-binding protein (vWbp), which bind prothrombin to activate its conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin, and clumping factors A and B (ClfA and ClfB), which directly bind fibrinogen43,44. Additionally, S. aureus secretes immune evasion proteins, such as chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus (CHIPS) and staphylococcal complement inhibitor (SCIN), to counteract initial acute immune responses45. As S. aureus cells begin to aggregate and establish a colony, large numbers of immune cells, mostly neutrophils, infiltrate the area and become necrotic as a result of direct and indirect killing46. The layer of mostly necrotic host immune cells inadvertently creates an additional protective barrier, preventing newly recruited host immune cells from penetrating the abscess and killing the bacteria41.

Within a SAC, bacterial cells are largely devoid of high amounts of nutrients and oxygen; therefore, to survive in this environment, S. aureus must tailor its gene expression according to nutrient availability. One nutrient required for growth and proliferation of nearly all microorganisms is iron. S. aureus utilizes the iron-scavenging proteins IsdA, IsdB and IsdH to bind haemoglobin to extract haem as a source of iron47,48. Extracellular adherence protein (Eap) and the ESAT6 secretion system (Ess) pathway, a non-canonical protein secretion pathway, have also been shown to promote SAC persistence particularly in the later stages of disease47. Similar to biofilms, the cells within a SAC can be considered a metabolically diverse population contributing to antibiotic tolerance and resistance to immune cell attack. Ultimately, the only effective means of eradication is abscess disruption or debridement.

Persister cells and SCVs

Skeletal infections also involve bacteria existing as persister cells and as SCVs, which can arise due to environmental triggers such as oxidative stress, nutrient limitation, intracellular residence and low pH. SCVs can be present in all of the persistence mechanisms described above (intracellular infection, OLCN invasion, biofilms and abscesses), further contributing to infection severity and complicating treatment.

SCVs are characterized by small colony size, slow growth, and reduced virulence and have been described in biopsies of patients with skeletal infection49. The low virulence of these strains does not seem to reduce fitness to cause disease and may support evasion of host immune defences, although the precise mechanisms remain to be determined50. By contrast, persister cells are a sub-set of any bacterial population characterized by their ability to survive high bactericidal antibiotic concentrations without exhibiting any antibiotic resistance mechanism51. In this case, persistence is believed to be a naturally occurring heterogeneity phenomenon within bacterial populations and induced by the (p)ppGpp alarmone-induced stringent response, the SOS response, and biofilm formation52. Both SCV and persister cells can contribute to failure of antibiotic therapy and recurrence of infection, and are at present not adequately addressed in current medical treatment options for patients with skeletal infections52.

Other pathogens in skeletal infections

Factors affecting infection

Non-staphylococcal pathogens are also capable of causing bone infection and may have increased importance in certain anatomical locations or patient populations (Table 1; Fig. 3). The route of infection is also important. For example, direct contamination of the surgical site is often caused by skin colonizers like CoNS53,54, whereas haematogenous infection often involves pathogens well equipped to survive in the bloodstream such as Streptococcus spp. Furthermore, fracture-related infections can be caused by various environmental pathogens such as Enterobacter spp., P. aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii, the latter commonly isolated from combat-related injuries.

Although Staphylococcus spp. are the most common pathogens across all skeletal infection types, other pathogens frequently cause infection within specific infection classes or patient populations. The figure highlights lesser common pathogens, beyond Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp., that are uniquely associated with skeletal infections across the human body. Salmonella spp. is most common in individuals with sickling haemoglobinopathies, Haemophilus influenza and Kingella kingae are most common in children, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae is found in sexually active patients.

The presence of an implant is another crucial factor for infection by less pathogenic or opportunistic organisms. For example, S. epidermidis accounts for up to 25% of PJI (Table 1; Fig. 3). Similar to S. aureus, it is a skin commensal organism and rarely causes invasive infection in immunocompetent hosts; however, it can serve as an opportunistic pathogen, particularly in the setting of a medical device55.

C. acnes is the most prevalent bacterial pathogen in upper extremity infections resulting in osteomyelitis. C. acnes is a facultative anaerobic, Gram-positive bacillus that has been isolated in 5% of lower extremity PJI cases and over 50% of shoulder PJI cases56,57. It is both a normal part of the microbiota of the skin, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands and an opportunistic pathogen in acne vulgaris and implant-associated osteomyelitis58. C. acnes poses an additional challenge in the setting of implant-associated infection because clinical diagnostic criteria rely heavily on tissue culture results; however, this organism is difficult to culture, requiring repetitive testing and extended incubation times of up to 2 weeks59. Similar to S. epidermidis, in vivo studies suggest that C. acnes-caused osteomyelitis is dependent on the presence of an implant, emphasizing the crucial role of biofilm formation in its pathogenesis60.

As mentioned, certain microorganisms have a predilection for particular patient populations (Fig. 3). For example, Salmonella spp. are unique pathogens in the setting of haematogenous osteomyelitis in patients with haemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell anaemia, due to their functional asplenia and resulting deficient splenic clearance of opsonized encapsulated organisms61. In children, Kingella kingae has replaced Haemophilus influenzae as the predominant cause of septic arthritis since the advent of the H. influenzae vaccination. Gram-negative cocci, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, remain an important component of the differential diagnosis in septic arthritis in sexually active individuals62. Finally, in the setting of tissue ischaemia, such as the microvascular ischaemia of diabetic foot wounds, or in the setting of immunocompromised hosts, Gram-negative bacterial infections and polymicrobial infections become more prevalent. Although Staphylococcus spp. are the most prevalent pathogen across all infection types (Table 1), other pathogens can infect bone in specific circumstances and should be considered during disease diagnosis and treatment.

Pathogenesis

Despite being known as a less pathogenic species, S. epidermidis is commonly isolated from osteomyelitis cases involving an implant or an immunocompromised host. Although most osteomyelitis studies have focused on S. aureus, opportunistic infection by the skin-colonizer S. epidermidis remains an important area of research. Similar to S. aureus, S. epidermidis adheres to implant surfaces via adhesins such as autolysin (AltE), extracellular DNA, staphylococcal surface proteins 1 and 2, and cell wall-anchored proteins such as MSCRAMMs55. S. epidermidis is capable of forming a robust biofilm on the implant surface, which contributes to immune evasion and antimicrobial resistance63. However, S. epidermidis lacks the diversity of virulence factors expressed by S. aureus and, as a result, tends to manifest as a more indolent, less inflammatory infection64.

Streptococcus spp. are the second most common bacteria isolated from implant-associated osteomyelitis, of which S. agalactiae is the most common species65,66,67. Recent studies found that S. agalactiae infection induces significantly less osteolysis than S. aureus. Additionally, S. agalactiae infection showed decreased abscess formation compared with S. aureus and zero S. agalactiae colony forming units were recovered from the implant68. These findings support the notion that S. agalactiae does not form robust implant-associated biofilms and suggest a possible explanation for the improved efficacy of debridement and antibiotic and implant retention therapy observed in streptococcal infections. Additionally, S. agalactiae may preferentially colonize the vascular network within bone68 as opposed to the OLCN invasion observed in S. aureus infection.

Indeed, many microbial pathogens beyond Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. have been reported to form robust biofilms. For example, osteomyelitis-causing Gram-positive Enterococcus spp. have been reported to form biofilms in the setting of an implant material69. Although the genetic determinants of Enterococcus spp. biofilm formation are not well understood, recent work has shown that ahrC, encoding a transcriptional regulator, and eep, encoding a membrane metalloprotease, contribute to Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation70.

Notably, Gram-negative P. aeruginosa is a notorious biofilm-forming bacterium known specifically for infections in the setting of cystic fibrosis and chronic wounds71. Although few studies have investigated P. aeruginosa biofilms specifically in the context of osteomyelitis, P. aeruginosa biofilms are known to contribute to antibiotic resistance and infection persistence, and should therefore be considered as an important mechanism of pathogenesis in osteomyelitis72.

Furthermore, multiple osteomyelitis-causing pathogens have been reported to form SCVs. In fact, the SCV phenotype was originally described for Salmonella enterica73 and has since been reported in a range of osteomyelitis-causing pathogens, including S. epidermidis74, E. coli75 and P. aeruginosa76. However, the prevalence of SCVs of pathogens beyond S. aureus in osteomyelitis is not well known and requires further research.

Polymicrobial infections

Polymicrobial infections are the cause of approximately one-third of post-traumatic osteomyelitis cases77, 6–21% of PJI65, and as high as 83% of diabetic foot infections78. Unsurprisingly, the most prevalent organism in polymicrobial osteomyelitis is S. aureus, with co-infecting bacteria varying from opportunistic to pathogenic bacteria. In cases of infection site contamination (non-haematogenous), contamination by skin-colonizers commonly includes CoNS, whereas contamination by environmental organisms can be much more diverse, including E. coli, Enterobacter spp., P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, Bacillus spp. and Enterococcus spp.

Oftentimes, polymicrobial infections are associated with poorer outcomes and increased infection severity79. This can be explained by microbial synergism that induces specific virulence traits or modulates the host immune response80. Interestingly, a study showed that S. aureus virulence is augmented by the addition of skin commensal organisms or peptidoglycan, acting as ‘pro-infectious agents’81. On the other hand, commensal organisms are also know to play a protective role against pathogenic infection, supported by recent work from a study in which CoNS species, such as Staphylococcus simulans, inhibited S. aureus quorum sensing and reduced S. aureus-induced dermonecrosis in a murine model of skin infection82.

To expand our understanding of polymicrobial interactions in the setting of skeletal infection and to inform effective treatments, preclinical models of polymicrobial osteomyelitis are required. Currently, the number of studies investigating polymicrobial skeletal infection models are limited and not well established. Organisms studied in these models include A. baumannii, E. coli and P. aeruginosa in combination with S. aureus83,84,85. In these models, S. aureus oftentimes outcompetes the co-infecting organism in the bone setting or on the implant material, resulting in fewer non-S. aureus colony forming units84,85. This is explained in part by the arsenal of virulence mechanisms uniquely employed by S. aureus to thrive in the bone microenvironment.

More studies are required to understand specific microbial interactions that lead to increased severity in polymicrobial infections. One study showed that the presence of P. aeruginosa in bone tissue was increased during co-infection with S. aureus compared with P. aeruginosa monomicrobial infection83, suggesting a role for microbial synergism in this model. However, the mechanism for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus synergism in skeletal infection is not yet understood.

Host responses and immune evasion

The immune system plays a crucial role in the defence against skeletal infections and maintaining bone homeostasis. This section describes the interaction between the immune system (innate and adaptive) and essential S. aureus virulence proteins during skeletal infections. In particular, immune activation, suppression and regulatory mechanisms will be discussed during chronic implant-associated osteomyelitis.

Tissue-specific immune responses

The ability of S. aureus to survive long-term in the bone niche is attributed to the expression of an array of virulence factors, including adhesins, immunomodulatory proteins, toxins and superantigens with redundant functions. Figure 4 illustrates the crucial proteins utilized by S. aureus to manipulate innate and adaptive host immune responses.

Virulence proteins enable Staphylococcus aureus to successfully evade host immune responses. a | S. aureus utilizes several cell-associated microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) and secretory proteins to thwart innate host defences. The bacterial cell surface protein SasG promotes cell adhesion, intracellular survival within neutrophils, macrophages and non-professional phagocytes. S. aureus impedes complement-mediated opsonization and phagocytosis by trapping complement proteins using extracellular fibronectin-binding protein (Efb), SpA and Sbi; inhibiting neutrophil recruitment using staphylococcal complement inhibitor (SCIN), chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus (CHIPS), SpA and coagulase (CoA); and secreting pore-forming toxins (α-haemolysin (Hla), β-haemolysin, γ-haemolysin (HlgAB, HlgCB), leukocidin AB (LukAB) and Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL)) to disrupt host membranes to kill innate cells. Superantigens (S. aureus enterotoxin B and C (SEB, SEC) and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST1)) contribute to immune evasion by 1) skewing M2-macrophage polarization, 2) promoting myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) formation, leading to decreased phagocytosis, 3) promoting staphylococcal abscess community formation, and 4) contributing to dysregulation of antigen presentation and cytokine production that affects T and B cell activation. b | On the adaptive immunity side, superantigens can crosslink T cell receptors on tissue-resident T cells to cause antigen-independent stimulation, ultimately causing cell exhaustion. Hla, LukED and phenol soluble modulins (PSMs) can interfere with T cell differentiation and activation, and cause apoptosis. The multifunctional SpA protein can impede B cell function and staphylokinase (Sak) can cleave IgG to prevent antibody-mediated phagocytosis. Antibodies can either be protective or pathogenic during S. aureus infection, with anti-IsdB antibodies facilitating S. aureus survival within ‘Trojan horse’ macrophages causing sepsis, and anti-Gmd antibodies preventing biofilm formation and protecting against skeletal infections. Atl, autolysin; ClfA/B, clumping factor A/B; FnBP, fibronectin-binding protein.

S. aureus-mediated manipulation of innate immune cells

Innate immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, provide the first line of defence against S. aureus skeletal infections. Figure 4a depicts important virulence proteins and mechanisms employed by S. aureus to evade innate immune cells.

Planktonic S. aureus cells are effectively killed by innate immune cells through phagocytosis, production of antimicrobial peptides, oxidative bursts, secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps, which trap bacteria86,87. However, in chronic skeletal infections, such as implant-associated osteomyelitis, S. aureus persists as biofilms, leading to decreased neutrophil activity against S. aureus88. S. aureus also secretes pore-forming toxins (for example, Hla, β-haemolysins, γ-haemolysins (HlgAB and HlgCB), leukocidin A/B (LukAB) and PVL) that directly kill neutrophils, macrophages and other antigen-presenting cells by damaging cellular membranes89,90. Interestingly, S. aureus persists as a biofilm in the bone niche during chronic osteomyelitis by downregulating these toxins, especially Hla and LukAB91,92.

In skeletal infections, S. aureus biofilms can actively evade toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR9 recognition due to bacterial ligand inaccessibility and skew macrophage responses towards an anti-inflammatory or profibrotic M2 phenotype93. A typical M2 macrophage response is characterized by attenuated antimicrobial peptide production, increased arginase 1, IL-4 and IL-10 expression, and decreased inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression93,94, all of which could lead to profibrotic responses creating abscesses during chronic implant-associated skeletal infections. Additionally, S. aureus also modulates the expression of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are a heterogeneous subset of immature monocytes and granulocytes95. In a murine osteomyelitis model, one study showed that MDSCs actively suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine production and T cell recruitment to the infection site, thus enabling bacterial persistence96. It was also demonstrated that superantigens, such as staphylococcal enterotoxins, play an important role in modulating MDSC generation, which affects bacterial persistence97.

Additionally, S. aureus can survive within phagocytic cells and in non-professional phagocytes such as osteocytes and osteoblasts in the bone niche during chronic osteomyelitis17,20,98. The internalization process within these cells is achieved by MSCRAMMs FnBPA and FnBPB binding to fibrinogen, and connecting to α5β1 integrins on macrophages or neutrophils13. In addition, other MSCRAMMs, such as ClfA, ClfB, surface-anchored proteins (SdrC, SdrD and SdrE) and the surface protein SasG, promote bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation on both indwelling prosthetic devices and plasma-coated biological surfaces99,100. The role of these adhesion proteins pertaining to S. aureus immune evasion and pathogenesis has been described elsewhere100. In addition to intracellular survival in phagocytes, S. aureus also impedes complement-mediated opsonization and phagocytosis through secretion of virulence proteins such as CHIPS, SCIN, CoA and extracellular fibrinogen binding protein (Efb)54,101.

S. aureus-mediated manipulation of adaptive immune cells

Adaptive immunity against S. aureus encompasses cell-mediated T cell responses and humoral antibody responses mediated by B cells. Figure 4b illustrates the mechanisms and related immunomodulatory proteins utilized by this pathogen to evade adaptive immune cells.

Research over the past two decades has accumulated evidence that T cells and its subsets are essential to host defence against S. aureus102. Murine osteomyelitis models have shown that S. aureus biofilms skew CD4+ T helper (TH) cell responses towards TH1 and TH17 cells, which causes ineffective clearance of intracellular pathogens103. In contrast to these studies, one study found minimal T cell infiltration to the biofilm infection site in human S. aureus PJI104. These studies highlight that the immune correlates of infection and protection in mice often diverge from human responses. A small animal model with a functional human immune system could attempt to bridge this gap. It was recently demonstrated that humanized NSG (NOD scid gamma) mice suffered exacerbated S. aureus osteomyelitis compared with normal C57BL/6J mice and an increased susceptibility to S. aureus osteomyelitis-induced sepsis. Interestingly, the authors observed infiltration and proliferation of human CD3+T-bet+ cells adjacent to SACs in the bone marrow of infected humanized NSG mice105.

The aforementioned conventional T cell responses require S. aureus antigen presentation and interaction with T cell receptors (TCRs). However, superantigens such as TSST1 can crosslink the Vβ chain of TCRs from tissue-resident T cells, causing antigen-independent T cell stimulation and massive secretion of several cytokines106. One study posited that such strong T cell activation could ultimately lead to impaired memory T cell responses and anergy107. Nonetheless, the consequence of superantigen expression and its influence on adaptive immunity needs to be fully elucidated. Other pore-forming toxins, such as Hla and PSMs, can interfere with T cell differentiation and activation and also cause T cell apoptosis89,108,109. In addition, S. aureus can manipulate B cell survival and function and influence humoral antibody responses. It also secretes the multifunctional protein SpA, which binds to the Fcγ and Fab domains of certain antibodies110,111,112, blocking antibody-mediated phagocytosis and concurrently initiating proliferative B cell apoptosis113,114. Additionally, the S. aureus enzyme staphylokinase (Sak) can directly degrade IgG. Sak can strongly activate human plasminogen on cell surfaces, leading to cleavage and degradation of IgG115. The importance of humoral responses and anti-S. aureus antibody-mediated protective immunity is discussed in the subsequent section.

Protective versus susceptible immune responses to S. aureus

All humans develop anti-S. aureus antibodies due to life-long exposure to S. aureus through nasal carriage or prior infections. However, the presence of antibodies does not confer protection against future infections and the antibody repertoire against S. aureus, especially in healthy individuals, is highly variable116. Elucidating pathogen-specific antibodies to S. aureus and understanding the functional role of the protective versus susceptible nature of an individual’s antibody response is essential for the development of successful immunotherapies against S. aureus. Recent studies have identified pathogenic antibody responses against haem-scavenging IsdB during S. aureus osteomyelitis in mice and humans, leading to susceptible host immunity117,118. Surprisingly, patients from an international biospecimen registry119 with high circulating anti-IsdB antibody titres were more likely to have adverse outcomes (arthrodesis, reinfection, amputation and sepsis leading to death) from bone infection118. Interestingly, utilizing preclinical mouse models, it was demonstrated that anti-IsdB antibodies facilitate S. aureus internalization in ‘Trojan horse’ macrophages120, followed by dissemination to the bloodstream and internal organs34,121. Indeed, large amounts of ‘Trojan horse’ leukocytes were observed in patients that succumbed to S. aureus osteomyelitis-induced sepsis and death34. Perhaps these mechanisms explain the failure of a 8,000-person cohort phase II/III clinical trial of an IsdB active vaccine (Merck V710), where individuals in the vaccinated group had a fivefold increase in mortality induced by multiple organ sepsis122.

In contrast to anti-IsdB antibodies, antibodies to the glucosaminidase (Gmd) subunit of S. aureus autolysin (Atl) can elicit protection against S. aureus osteomyelitis in mice123,124. Most interestingly, high levels of anti-Gmd antibodies in patients correlated with a marked reduction in adverse outcomes due to S. aureus infection125, suggesting a protective response. In agreement with the protective humoral immune proteome hypothesis, patients with high IgG concentrations against other S. aureus antigens, such as amidase (Amd), IsdH, CHIPS, SCIN and Hla, had a significant reduction in adverse outcomes118. The protective potential of anti-S. aureus antibody responses against toxins and superantigens has also been explored126,127. In particular, the lack of anti-TSST1 antibodies correlated with increased risks of S. aureus toxic shock syndrome106. Collectively, these studies make a strong case for prophylactic vaccines that can reverse this susceptibility towards a protective immune proteome before elective orthopaedic surgery.

Immune responses to other pathogens

CoNS are second only to S. aureus as the most prevalent species encountered in skeletal infections involving implants, although the clinical presentation is often milder and more chronic in nature. The lack of virulence factors, such as immunotoxins or immune-evasion mechanisms, in S. epidermidis compared with S. aureus may at least partially explain this observation and may be responsible for the distinctly different immune responses to both pathogens. As is common amongst bacterial species, S. epidermidis triggers immune responses partly via TLR2 (ref.128) or NOD-like receptor recognition of cell wall molecules, including lipoproteins, lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan128,129,130. S. epidermidis also has a number of secreted factors, such as PSMs, that activate the human immune system131. However, the immune response to S. epidermidis leads to markedly higher induction of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, for example, during skin colonization, than S. aureus132, which matches the clinical picture of S. epidermidis as a persistent but not aggressive pathogen in skeletal infections. The immune response to other pathogens has been less well studied. C. acnes has been extensively studied in the context of acne, where it has been shown to activate TLR2 and TLR4, leading to activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signalling pathways and ultimately resulting in production of pro-inflammatory molecules such as IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-6 (refs133,134). Further investigations into C. acnes host–pathogen interactions are required to provide a more complete understanding of the key virulence factors for skeletal infection and mechanisms responsible for the relatively moderate osteolysis commonly associated with this microorganism.

Clinical management of skeletal infections

Classification of osteomyelitis

Classification of osteomyelitis remains controversial and many different classification systems have been used to better describe the spectrum of disease39. Clinically, one of the most common ways to classify osteomyelitis has traditionally been based on temporal definitions135,136,137, such as acute versus chronic infection, with the goal of defining the need for less aggressive (antibiotics alone) versus surgical treatments. It is now known that temporal thresholds do not exist, and clinical studies have used a wide range of temporal definitions from 1–2 weeks to 3–6 months138. The formation of biofilms or OLCN invasion is likely the pathological event that defines a recalcitrant infection that may need more aggressive treatment; however, a temporal definition for these events is lacking. Common characteristics used to classify osteomyelitis include location and/or extent of bone involvement, the extent of necessary bone resection, presence of abscesses or sequestrum, aetiology of infection (haematogenous versus contiguous spread, for example), or need for soft tissue coverage during surgery135,137,139,140. Another important variable that may help predict outcomes of osteomyelitis treatment is the immune status of the host and whether they are capable of withstanding surgical treatment139,140,141. One of the most common and well-accepted staging systems that is used is the Cierny–Mader classification, which tries to define the area of bone involvement (medullary — type I; superficial — type II; localized — type III; and diffuse — type IV) and the physiological class of the host (A — immunocompetent; B — locally or systemically compromised; and C — a host that will not tolerate surgery)141. This emphasizes the disease extent and the overall health of the affected patient, which are likely to be associated with treatment outcome.

Diagnosis, prevention and treatment

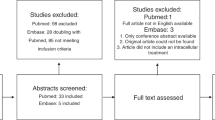

Osteomyelitis is a heterogeneous disease depending on the anatomical site, presence of an implant, and host–pathogen characteristics; however, some general principles in diagnosis and treatment can be defined. The standard approach to a patient with suspected osteomyelitis is summarized in Box 1. Recent advances in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis include (1) standardization of diagnostic criteria; (2) the emergence of new biomarkers of infection; and (3) improvements in methods for organism identification. In recent years, national and international groups of experts have attempted to provide evidence-based, standardized reporting of musculoskeletal infection diagnosis and treatment (Box 1). These are important first steps in improving communication between clinicians and providing a standard for clinical studies reporting. Serum and synovial fluid tests are frequently used as an initial screening in suspected cases of osteomyelitis (Box 1). In recent years, the identification of novel biomarkers has provided the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy. For example, α-defensin, which is an antimicrobial peptide released mostly by activated neutrophils, has become a novel synovial fluid biomarker for the diagnosis of PJI142. In cases of suspected osteomyelitis, advanced imaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging, or nuclear medicine studies, such as technetium-99m bone scans, are typically used to identify the anatomical location of osteomyelitis and the presence of associated abscesses and to assist with obtaining image-guided tissue biopsy specimens (Box 1). Most diagnostic and treatment criteria rely on the identification of the infectious organism; however, culture-negative infection can represent up to 20% of cases in osteomyelitis, creating diagnostic and treatment uncertainty. Novel methods to improve organism identification include matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF MS), genomic sequencing, and implant sonication. MALDI–TOF MS analysis enables the identification of bacterial species from colonies directly from existing media or blood culture, which was a significant improvement in time, labour and cost compared with prior methods143. Given the concomitant existence of implant-associated biofilms in many types of osteomyelitis, direct cultures of fluid after sonication of the retrieved implant is another way to improve the sensitivity of organism identification144. Genomic sequencing-based methods have been an important area of investigation in recent years in diagnosing skeletal infections. Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based methods involve both targeted or untargeted massive parallel DNA sequencing to identify both human and microbiological nucleic acids within a sample. Untargeted methods of NGS, such as metagenomic sequencing, have been shown to be accurate in identifying known pathogens from culture-positive PJIs (95% concordance with sonicate fluid culture) while also identifying organisms in over 40% of culture-negative infections that otherwise met diagnostic criteria for infection145. Concerns about genomic sequencing-based technology include cost and the identification of colonizing versus actively infectious organisms. For example, presumed aseptic primary joint replacements with no clinical signs of infection identified an infectious organism in 35% of cases using NGS, suggesting that further refinement is necessary to identify active infections146.

Infection prevention is another crucial method to reduce the impact of osteomyelitis. Systemic antibiotic therapy prior to surgical incision in implant-associated surgery is one of the most effective evidence-based preventive therapies, and forms part of the Surgical Care Improvement Project national guidelines on infection prevention147. However, the use of local antibiotics, including antibiotic powder, beads and antibiotic-eluting cement, for infection prevention has yielded mixed results. For example, certain combinations of antibiotic-eluting cement may decrease the risk of PJI in high-risk patient populations such as femoral neck fractures, veteran patients and paediatric spinal deformity surgery148,149,150. However, other studies have shown no benefit to infection prophylaxis and poor cost-effectiveness for commercially available antibiotic bone cement formulations when used across a broad population151,152,153. One strategy for infection prevention is active immunization. Unfortunately, vaccine strategies targeting components of the S. aureus cell wall, such as poly-N-acetyl glucosamine, lipoteichoic acid, capsular polysaccharides or iron-acquisition such as IsdB, have been unsuccessful beyond phase I clinical trials122,154,155. Newer vaccine strategies targeting virulence factors (Hla and PVL) or multivalent vaccines targeting capsular or surface antigens have not progressed beyond early-stage trials156,157. Another promising early-stage systemic treatment in osteomyelitis is the use of immunotherapy. For example, monoclonal antibodies targeting Hla, biocomponent cytotoxins and ClfA showed a significant reduction in infection severity using a rabbit model of S. aureus PJI158.

Establishing both local and systemic infection control are crucial principles to treating osteomyelitis in adults. Surgical debridement and systemic antibiotics are required in most adult patients with osteomyelitis. The overall success of surgical treatment varies widely and depends on anatomical location, soft tissue integrity, presence or absence of an implant, presence of a deep abscess or biofilm, immune status of the host, and the infecting organism. For example, infection cure rates vary between 50–75% for debridement and implant retention in the setting of acute postoperative or haematogenous infection in lower extremity joint replacement and 60–90% for chronic infections treated with two-staged implant removal159,160,161,162. For hospitalized patients with diabetic foot infections, either minor or major amputations are needed in up to 70% of cases163. The infecting organism may influence outcomes, and Staphylococcus spp. may have worse outcomes with debridement and implant retention relative to other organisms in infected lower extremity joint replacement164. In contrast to adults, children with haematogenous osteomyelitis may be treated with systemic antibiotics alone unless deep abscess or intra-articular involvement is present or in cases with MRSA165. In addition to surgical debridement, systemic antibiotic therapy is a crucial component to osteomyelitis treatment. Principles of systemic antibiotic therapy in osteomyelitis include organism-directed therapy based on sensitivities, use of agents that achieve appropriate osseous concentrations, and the use of anti-biofilm agents in the setting of a retained implant. Rifampicin is typically used as an anti-biofilm agent in implant-associated infections; however, rapid resistance can develop when used as a monotherapy and it is therefore used in combination with other systemic agents166. One strategy to improve treatment in osteomyelitis is the development of novel antibiotics with higher oral bioavailability, broad spectrums of activity against resistant organisms and longer half-lives to shorten the necessary duration of treatment167. One novel approach to target intracellular bacteria used an antibody–antibiotic conjugate consisting of a monoclonal antibody against teichoic acids bound to a rifamycin class antibiotic188. This antibody–antibiotic conjugate binds to the cell surface and, upon opsonization, the proteolytic environment of the phagolysosome causes release of the active antibiotic form, allowing the targeting of intracellular organisms188.

Local treatments have been tried with a varying degree of success in osteomyelitis therapy. The use of topical antibiotic therapy is controversial in the setting of osteomyelitis treatment. Traditionally, antibiotic-eluting beads have been used as a local antibiotic delivery source with variable effects on treatment outcomes depending on the anatomical location examined168,169,170. The two-stage exchange for PJI, with a first-stage placement of an antibiotic eluting spacer, is considered the standard of care for chronic PJI; however, the necessity of the antibiotic elution from the spacer versus limb support and treatment of dead space (empty space from excised tissue) remains controversial. Similar to infection prevention, topical antibiotic powder may improve reinfection rates in combination with other local treatments such as dilute povidone-iodine after treatment of chronic PJI171. Other local treatments include the use of novel antimicrobial surface coatings. For example, silver-coated and gentamicin-coated prostheses have been used clinically in megaprostheses for large periarticular bone defects and for fracture fixation, respectively172,173. Bacteriophage therapy has generated interest for many decades, and recent studies have investigated it as an adjuvant in the treatment of osteomyelitis174. For example, in a murine model of implant-associated osteomyelitis, the use of a combination of systemic and locally applied bacteriophage-derived lysin (PlySs2), aimed at targeting both planktonic and biofilm-associated bacteria, improved S. aureus infection eradication after debridement and implant retention175. Phage therapy has been used for topical delivery in humans for indications such as diabetic toe ulcers and limited cases of other lower extremity osteomyelitis; however, these studies involved small patient numbers without control groups133.

Conclusions and perspectives

Based on the gravity of the clinical problem and advances in experimental, translational and clinical research technologies, there has been a resurgence of bone infection research that has elucidated novel mechanisms of microbial pathogenesis, biofilm formation, protective versus pathogenic host immunity, and major challenges that need to be overcome for the development of effective diagnostics, vaccines and therapies. Moreover, agreement on these crucial issues has been established by international consensus176,177,178,179. Although the bulk of this research is focused on S. aureus, based on its prevalence in clinical bone infections and the poor outcomes associated with these cases, studies of other challenging pathogens (for example, CoNS, Streptococcus spp., Mycobacterium spp. and Pseudomonas spp.) as well as of opportunistic bacteria in polymicrobial infections are active areas of investigation.

Currently, diagnosing bone infection remains a major challenge based on the insensitivity of standard-of-care cultures, which fail to detect indolent bacteria due to biopsy limitations, and ongoing antibiotic therapy that can cause false negative results. Although the advent of NGS has overcome some of these sensitivity issues, this diagnostic suffers from specificity issues related to contamination and our lack of understanding between alterations in the microbiome of polymicrobial infections and disease-causing microorganisms. Similarly, diagnostics of host factors have also improved but challenges of sensitivity and specificity remain. In the case of inflammatory cytokines (that is, c-reactive protein and α-defensin), detection of high levels of these proteins in serum and synovial fluid combined with clinical signs and symptoms have proven to be very effective diagnostics for infection but are incapable of determining the virulent organism. By contrast, assessment of pathogen-specific IgGs can provide specificity; however, immunological memory against the most common pathogens presents sensitivity challenges that may require longitudinal assessment of antigen-specific lymphocytes.

The recent elucidation of the distinct mechanisms of bacterial invasion, colonization and biofilm formation during the establishment of bone infection and chronic osteomyelitis highlight novel targets and approaches for prophylaxis and therapy. Based on the discovery of bacterial colonization of the OLCN, new approaches with bisphosphonate-conjugated antibiotics180 and locally delivered microspheres181 to enhanced bone targeting and sustained antibiotics release are being tested. Additionally, there are several phage therapies being investigated as novel treatments for complicated bone infections182.

To overcome the dismal history of vaccine development for osteomyelitis, the field has taken a step back from approaches with accelerated development from antigen discovery to clinical trials, and has invested in sophisticated small, intermediate and clinically relevant animal models183, which are designed with specific outcomes to quantify: in vivo bacterial growth with bioluminescence imaging184 and fluorescent intravital microscopy185, biofilm formation on bone and implants186, osteolysis187 and osseous integration64, and human immune responses105. From this work, the field has gained major insights into protective versus pathogenic immune responses during bone infection121, which has translational potential into prognostics118 and promising vaccines188. With this knowledge, passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies to these bacterial targets in synergy with antibiotic treatment can now be investigated as therapies to reduce the very high reinfection rates following revision surgery for implant-associated osteomyelitis.

References

Kremers, H. M. et al. Trends in the epidemiology of osteomyelitis: a population-based study, 1969 to 2009. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 97, 837 (2015).

Tshefu, K., Zimmerli, W. & Waldvogel, F. A. Short-term administration of rifampin in the prevention or eradication of infection due to foreign bodies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5 (Suppl. 3), S474–S480 (1983).

Li, D. et al. Quantitative mouse model of implant-associated osteomyelitis and the kinetics of microbial growth, osteolysis, and humoral immunity. J. Orthop. Res. 26, 96–105 (2008).

Arens, D. et al. A rabbit humerus model of plating and nailing osteosynthesis with and without Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Eur. Cell Mater. 30, 148–161 (2015).

Shiels, S. M., Bedigrew, K. M. & Wenke, J. C. Development of a hematogenous implant-related infection in a rat model. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 255 (2015).

Joyce, K., Sakai, D. & Pandit, A. Preclinical models of vertebral osteomyelitis and associated infections: current models and recommendations for study design. JOR Spine 4, e1142 (2021).

Farnsworth, C. W. et al. A humoral immune defect distinguishes the response to Staphylococcus aureus infections in mice with obesity and type 2 diabetes from that in mice with type 1 diabetes. Infect. Immun. 83, 2264–2274 (2015).

Dudareva, M. et al. The microbiology of chronic osteomyelitis: changes over ten years. J. Infect. 79, 189–198 (2019).

Libraty, D. H., Patkar, C. & Torres, B. Staphylococcus aureus reactivation osteomyelitis after 75 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 481–482 (2012).

Garzoni, C. & Kelley, W. L. Return of the Trojan horse: intracellular phenotype switching and immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO Mol. Med. 3, 115–117 (2011).

Kintarak, S., Whawell, S. A., Speight, P. M., Packer, S. & Nair, S. P. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by human keratinocytes. Infect. Immun. 72, 5668–5675 (2004).

Fischetti, V. A. et al. Fibronectin binding protein and host cell tyrosine kinase are required for internalization of staphylococcus aureus by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67, 4673–4678 (1999).

Edwards, A. M., Potts, J. R., Josefsson, E. & Massey, R. C. Staphylococcus aureus host cell invasion and virulence in sepsis is facilitated by the multiple repeats within FnBPA. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000964 (2010).

Edwards, A. M., Potter, U., Meenan, N. A., Potts, J. R. & Massey, R. C. Staphylococcus aureus keratinocyte invasion is dependent upon multiple high-affinity fibronectin-binding repeats within FnBPA. PLoS ONE 6, e18899 (2011).

Ahmed, S. et al. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin binding proteins are essential for internalization by osteoblasts but do not account for differences in intracellular levels of bacteria. Infect. Immun. 69, 2872–2877 (2001).

Ellington, J. K. et al. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. A mechanism for the indolence of osteomyelitis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 85, 918–921 (2003).

Josse, J., Velard, F. & Gangloff, S. C. Staphylococcus aureus vs. osteoblast: relationship and consequences in osteomyelitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 5, 85 (2015).

Roper, P. M., Shao, C. & Veis, D. J. Multitasking by the OC lineage during bone infection: Bone resorption, immune modulation, and microbial niche. Cells 9, 2157 (2020).

Krauss, J. L. et al. Staphylococcus aureus infects osteoclasts and replicates intracellularly. mBio 9, e00415-18 (2019).

Yang, D. et al. Novel insights into staphylococcus aureus deep bone infections: the involvement of osteocytes. mBio 9, e00415-18 (2018).

Sendi, P. et al. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants in prosthetic joint infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43, 961–967 (2006).

Bosse, M. J., Gruber, H. E. & Ramp, W. K. Internalization of bacteria by osteoblasts in a patient with recurrent, long-term osteomyelitis: a case report. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 87, 1343–1347 (2005).

Alder, K. D. et al. Intracellular staphylococcus aureus in bone and joint infections: a mechanism of disease recurrence, inflammation, and bone and cartilage destruction. Bone 141, 115568 (2020).

de Mesy Bentley, K. L. et al. Evidence of Staphylococcus aureus deformation, proliferation, and migration in canaliculi of live cortical bone in murine models of osteomyelitis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 32, 985–990 (2017).

de Mesy Bentley, K. L., MacDonald, A., Schwarz, E. M. & Oh, I. Chronic osteomyelitis with staphylococcus aureus deformation in submicron canaliculi of osteocytes: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 8, e8 (2018).

Yu, B., Pacureanu, A., Olivier, C., Cloetens, P. & Peyrin, F. Assessment of the human bone lacuno-canalicular network at the nanoscale and impact of spatial resolution. Sci. Rep. 10, 4567 (2020).

Sunyer, R. et al. Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission. Science 353, 1157–1161 (2016).

Hsu, S., Thakar, R., Liepmann, D. & Li, S. Effects of shear stress on endothelial cell haptotaxis on micropatterned surfaces. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 401–409 (2005).

Masters, E. A. et al. An in vitro platform for elucidating the molecular genetics of S. aureus invasion of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network during chronic osteomyelitis. Nanomedicine 21, 102039 (2019).

Masters, E. A. et al. Identification of penicillin binding protein 4 (PBP4) as a critical factor for Staphylococcus aureus bone invasion during osteomyelitis in mice. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008988 (2020).

da Costa, T., de Oliveira, C., Chambers, H. & Chatterjee, S. PBP4: a new perspective on Staphylococcus aureus β-lactam resistance. Microorganisms 6, 57 (2018).

Schwarz, E. M. et al. Adjuvant antibiotic-loaded bone cement: concerns with current use and research to make it work. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 227–239 (2021).

Ricciardi, B. F. et al. Staphylococcus aureus evasion of host immunity in the setting of prosthetic joint infection: biofilm and beyond. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 11, 389–400 (2018).

Masters, E. A. et al. Evolving concepts in bone infection: redefining “biofilm”, “acute vs. chronic osteomyelitis”, “the immune proteome” and “local antibiotic therapy”. Bone Res. 7, 20 (2019).

Patti, J. M., Allen, B. L., McGavin, M. J. & Hook, M. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48, 585–617 (1994).

Cramton, S. E., Gerke, C., Schnell, N. F., Nichols, W. W. & Götz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 67, 5427–5433 (1999).

Le, K. Y. & Otto, M. Quorum-sensing regulation in staphylococci-an overview. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1174 (2015).

Carek, P. J., Dickerson, L. M. & Sack, J. L. Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Am. Fam. Physician 63, 2413–2420 (2001).

Kavanagh, N. et al. Staphylococcal osteomyelitis: disease progression, treatment challenges, and future directions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00084-17 (2018).

Brodie, B. C. Pathological researches respecting the diseases of joints. Med. Chir. Trans. 4, 210–280 (1813).

Cheng, A. G., DeDent, A. C., Schneewind, O. & Missiakas, D. A play in four acts: Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation. Trends Microbiol. 19, 225–232 (2011).

Hofstee, M. I. et al. Three-dimensional in vitro staphylococcus aureus abscess communities display antibiotic tolerance and protection from neutrophil clearance. Infect. Immun. 88, e00293-20 (2020).

Malachowa, N. et al. Contribution of Staphylococcus aureus Coagulases and Clumping Factor A to abscess formation in a rabbit model of skin and soft tissue infection. PLoS ONE 11, e0158293 (2016).

Farnsworth, C. W. et al. Adaptive upregulation of clumping factor A (ClfA) by staphylococcus aureus in the obese, type 2 diabetic host mediates increased virulence. Infect. Immun. 85, e01005-16 (2017).

Rooijakkers, S. H. et al. Early expression of SCIN and CHIPS drives instant immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Microbiol. 8, 1282–1293 (2006).

Kobayashi, S. D., Malachowa, N. & DeLeo, F. R. Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus abscesses. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1518–1527 (2015).

Cheng, A. G. et al. Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J. 23, 3393–3404 (2009).

Kim, H. K. et al. IsdA and IsdB antibodies protect mice against Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and lethal challenge. Vaccine 28, 6382–6392 (2010).

Kahl, B. C., Becker, K. & Loffler, B. Clinical significance and pathogenesis of staphylococcal small colony variants in persistent infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 29, 401–427 (2016).

Tuchscherr, L. et al. Clinical S. aureus isolates vary in their virulence to promote adaptation to the host. Toxins 11, 135 (2019).

Balaban, N. Q. et al. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 441–448 (2019).

Huemer, M., Mairpady Shambat, S., Brugger, S. D. & Zinkernagel, A. S. Antibiotic resistance and persistence-Implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep. 21, e51034 (2020).

Brown, M. M. & Horswill, A. R. Staphylococcus epidermidis — skin friend or foe? PLoS Pathog. 16, e1009026 (2020).

Foster, T. J. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 948–958 (2005).

Sabaté Brescó, M. et al. Pathogenic mechanisms and host interactions in Staphylococcus epidermidis device-related infection. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1401 (2017).

Akgün, D. et al. The role of implant sonication in the diagnosis of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 29, e222–e228 (2020).

Kheir, M. M. et al. Culturing periprosthetic joint infection: number of samples, growth duration, and organisms. J. Arthroplasty 33, 3531–3536.e1 (2018).

Achermann, Y., Goldstein, E. J., Coenye, T. & Shirtliff, M. E. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 419–440 (2014).

Pottinger, P. et al. Prognostic factors for bacterial cultures positive for Propionibacterium acnes and other organisms in a large series of revision shoulder arthroplasties performed for stiffness, pain, or loosening. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 94, 2075–2083 (2012).

Shiono, Y. et al. Delayed Propionibacterium acnes surgical site infections occur only in the presence of an implant. Sci. Rep. 6, 32758 (2016).

Ochocinski, D. et al. Life-threatening infectious complications in sickle cell disease: a concise narrative review. Front. Pediatrics 8, 38 (2020).

Clerc, O., Prod’hom, G., Greub, G., Zanetti, G. & Senn, L. Adult native septic arthritis: a review of 10 years of experience and lessons for empirical antibiotic therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 1168–1173 (2011).

Kranjec, C. et al. Staphylococcal biofilms: challenges and novel therapeutic perspectives. Antibiotics 10, 131 (2021).

Tomizawa, T. et al. Biofilm producing Staphylococcus epidermidis (RP62A strain) inhibits osseous integration without osteolysis and histopathology in a murine septic implant model. J. Orthop. Res. 38, 852–860 (2020).

Zeller, V. et al. Analysis of postoperative and hematogenous prosthetic joint-infection microbiological patterns in a large cohort. J. Infect. 76, 328–334 (2018).

Grammatopoulos, G. et al. Outcome following debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention in hip periprosthetic joint infection — an 18-year experience. J. Arthroplasty 32, 2248–2255 (2017).

Mahieu, R. et al. The prognosis of streptococcal prosthetic bone and joint infections depends on surgical management — a multicenter retrospective study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 85, 175–181 (2019).

Masters, E. A. et al. Distinct vasculotropic versus osteotropic features of S. agalactiae versus S. aureus implant-associated bone infection in mice. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 389–401 (2021).

Zaborowska, M. et al. Biofilm formation and antimicrobial susceptibility of staphylococci and enterococci from osteomyelitis associated with percutaneous orthopaedic implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 105, 2630–2640 (2017).

Frank, K. L. et al. Evaluation of the Enterococcus faecalis biofilm-associated virulence factors AhrC and Eep in rat foreign body osteomyelitis and in vitro biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance. PLoS ONE 10, e0130187 (2015).

Thi, M. T. T., Wibowo, D. & Rehm, B. H. A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8671 (2020).

Drenkard, E. & Ausubel, F. M. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 416, 740–743 (2002).

Proctor, R. A. et al. Small colony variants: a pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 295–305 (2006).

Baddour, L. M., Barker, L. P., Christensen, G. D., Parisi, J. T. & Simpson, W. A. Phenotypic variation of Staphylococcus epidermidis in infection of transvenous endocardial pacemaker electrodes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28, 676–679 (1990).

Colwell, C. A. Small colony variants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 52, 417–422 (1946).

Bryan, L. E. & Kwan, S. Aminoglycoside-resistant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa deficient in cytochrome d, nitrite reductase, and aerobic transport. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 19, 958–964 (1981).

Jorge, L. S., Fucuta, P. S., Nakazone, M. A., Chueire, A. G. & Costa, M. J. Outcomes and risk factors for polymicrobial posttraumatic osteomyelitis. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 3, 20–26 (2018).

Kaimkhani, G. M. et al. Pattern of infecting microorganisms and their susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs in patients with diabetic foot infections in a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus 10, e2872 (2018).

Issa, K. et al. Clinical differences between monomicrobial and polymicrobial vertebral osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 40, e370–e373 (2017).

Tay, W. H., Chong, K. K. L. & Kline, K. A. Polymicrobial–host interactions during infection. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3355–3371 (2016).

Boldock, E. et al. Human skin commensals augment Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 881–890 (2018).

Brown, M. M. et al. Novel peptide from commensal Staphylococcus simulans blocks methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing and protects host skin from damage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e00172-20 (2020).

Jennings, J., Beenken, K., Smeltzer, M. & Haggard, W. Preclinical models of polymicrobial infection for evaluation of antimicrobial combination devices. In Antimicrob. Combination Devices (ASTM International, 2011).

Boles, L. R. et al. Local delivery of amikacin and vancomycin from chitosan sponges prevent polymicrobial implant-associated biofilm. Military Med. 183, 459–465 (2018).

Collinet-Adler, S., Castro, C. A., Ledonio, C. G. T., Bechtold, J. E. & Tsukayama, D. T. Acinetobacter baumannii is not associated with osteomyelitis in a rat model: a pilot study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 469, 274–282 (2011).

Rigby, K. M. & DeLeo, F. R. Neutrophils in innate host defense against Staphylococcus aureus infections. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 237–259 (2012).

Lu, T., Kobayashi, S. D., Quinn, M. T. & Deleo, F. R. A NET outcome. Front. Immunol. 3, 365 (2012).

Seebach, E. & Kubatzky, K. F. Chronic implant-related bone infections-can immune modulation be a therapeutic strategy? Front. Immunol. 10, 1724 (2019).

Spaan, A. N., van Strijp, J. A. G. & Torres, V. J. Leukocidins: staphylococcal bi-component pore-forming toxins find their receptors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 435–447 (2017).

Seilie, E. S. & Bubeck Wardenburg, J. Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxins: The interface of pathogen and host complexity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 72, 101–116 (2017).

Trouillet-Assant, S. et al. Adaptive processes of Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the progression from acute to chronic bone and joint infections in patients. Cell Microbiol. 18, 1405–1414 (2016).

Jin, T. et al. Staphylococcal protein A, Panton-Valentine leukocidin and coagulase aggravate the bone loss and bone destruction in osteomyelitis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 32, 322–333 (2013).

Thurlow, L. R. et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J. Immunol. 186, 6585–6596 (2011).

Scherr, T. D. et al. Global transcriptome analysis of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in response to innate immune cells. Infect. Immun. 81, 4363–4376 (2013).

Gabrilovich, D. I. & Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 (2009).

Heim, C. E. et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to Staphylococcus aureus orthopedic biofilm infection. J. Immunol. 192, 3778–3792 (2014).

Stoll, H. et al. Staphylococcal enterotoxins dose-dependently modulate the generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8, 321 (2018).

Dapunt, U., Maurer, S., Giese, T., Gaida, M. M. & Hansch, G. M. The macrophage inflammatory proteins MIP1α (CCL3) and MIP2α (CXCL2) in implant-associated osteomyelitis: linking inflammation to bone degradation. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 728619 (2014).

Herman-Bausier, P., Formosa-Dague, C., Feuillie, C., Valotteau, C. & Dufrene, Y. F. Forces guiding staphylococcal adhesion. J. Struct. Biol. 197, 65–69 (2017).

Geoghegan, J. A. & Foster, T. J. Cell wall-anchored surface proteins of staphylococcus aureus: many proteins, multiple functions. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 409, 95–120 (2017).

Brandt, S. L., Putnam, N. E., Cassat, J. E. & Serezani, C. H. Innate immunity to staphylococcus aureus: evolving paradigms in soft tissue and invasive infections. J. Immunol. 200, 3871–3880 (2018).

Broker, B. M., Mrochen, D. & Peton, V. The T cell response to Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens 5, 31 (2016).

Prabhakara, R., Harro, J. M., Leid, J. G., Harris, M. & Shirtliff, M. E. Murine immune response to a chronic Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection. Infect. Immun. 79, 1789–1796 (2011).

Heim, C. E. et al. IL-12 promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment and bacterial persistence during Staphylococcus aureus orthopedic implant infection. J. Immunol. 194, 3861–3872 (2015).

Muthukrishnan, G. et al. Humanized mice exhibit exacerbated abscess formation and osteolysis during the establishment of implant-associated staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Front. Immunol. 12, 651515 (2021).

Xu, S. X. & McCormick, J. K. Staphylococcal superantigens in colonization and disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2, 52 (2012).

Watson, A. R., Janik, D. K. & Lee, W. T. Superantigen-induced CD4 memory T cell anergy. I. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B induces Fyn-mediated negative signaling. Cell Immunol. 276, 16–25 (2012).

Reyes-Robles, T. et al. Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED targets the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 to kill leukocytes and promote infection. Cell Host Microbe 14, 453–459 (2013).

Lee, B., Olaniyi, R., Kwiecinski, J. M. & Wardenburg, J. B. Staphylococcus aureus toxin suppresses antigen-specific T cell responses. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 1122–1127 (2020).

Moks, T. et al. Staphylococcal protein A consists of five IgG-binding domains. Eur. J. Biochem. 156, 637–643 (1986).

Cedergren, L., Andersson, R., Jansson, B., Uhlen, M. & Nilsson, B. Mutational analysis of the interaction between staphylococcal protein A and human IgG1. Protein Eng. 6, 441–448 (1993).

Schneewind, O., Model, P. & Fischetti, V. A. Sorting of protein A to the staphylococcal cell wall. Cell 70, 267–281 (1992).

Graille, M. et al. Crystal structure of a Staphylococcus aureus protein A domain complexed with the Fab fragment of a human IgM antibody: structural basis for recognition of B-cell receptors and superantigen activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5399–5404 (2000).

Goodyear, C. S. & Silverman, G. J. Death by a B cell superantigen: In vivo VH-targeted apoptotic supraclonal B cell deletion by a Staphylococcal Toxin. J. Exp. Med. 197, 1125–1139 (2003).

Rooijakkers, S. H., van Wamel, W. J., Ruyken, M., van Kessel, K. P. & van Strijp, J. A. Anti-opsonic properties of staphylokinase. Microbes Infect. 7, 476–484 (2005).

Meyer, T. C. et al. A comprehensive view on the human antibody repertoire against staphylococcus aureus antigens in the general population. Front. Immunol. 12, 651619 (2021).

Nishitani, K. et al. A diagnostic serum antibody test for patients with staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 473, 2735–2749 (2015).

Muthukrishnan, G. et al. Serum antibodies against Staphylococcus aureus can prognose treatment success in patients with bone infections. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 2169–2176 (2020).

Morgenstern, M. et al. The AO trauma CPP bone infection registry: epidemiology and outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bone infection. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 136–146 (2020).

Thwaites, G. E. & Gant, V. Are bloodstream leukocytes Trojan Horses for the metastasis of Staphylococcus aureus? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 215–222 (2011).

Nishitani, K. et al. IsdB antibody-mediated sepsis following S. aureus surgical site infection. JCI Insight 5, e141164 (2020).

Fowler, V. G. et al. Effect of an investigational vaccine for preventing Staphylococcus aureus infections after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA 309, 1368–1378 (2013).

Varrone, J. J., Li, D., Daiss, J. L. & Schwarz, E. M. Anti-glucosaminidase monoclonal antibodies as a passive immunization for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) orthopaedic infections. Bonekey Osteovision 8, 187–194 (2011).