Abstract

The study of moral judgements often centres on moral dilemmas in which options consistent with deontological perspectives (that is, emphasizing rules, individual rights and duties) are in conflict with options consistent with utilitarian judgements (that is, following the greater good based on consequences). Greene et al. (2009) showed that psychological and situational factors (for example, the intent of the agent or the presence of physical contact between the agent and the victim) can play an important role in moral dilemma judgements (for example, the trolley problem). Our knowledge is limited concerning both the universality of these effects outside the United States and the impact of culture on the situational and psychological factors affecting moral judgements. Thus, we empirically tested the universality of the effects of intent and personal force on moral dilemma judgements by replicating the experiments of Greene et al. in 45 countries from all inhabited continents. We found that personal force and its interaction with intention exert influence on moral judgements in the US and Western cultural clusters, replicating and expanding the original findings. Moreover, the personal force effect was present in all cultural clusters, suggesting it is culturally universal. The evidence for the cultural universality of the interaction effect was inconclusive in the Eastern and Southern cultural clusters (depending on exclusion criteria). We found no strong association between collectivism/individualism and moral dilemma judgements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Moral dilemmas can be portrayed as decisions between two main conflicting moral principles: utilitarian and deontological. Utilitarian (also referred to as consequentialist) philosophies1 hold that an action is morally acceptable if it maximizes well-being for the greatest number of people (in terms of saved lives, for example). On the other hand, deontological philosophy2 evaluates the morality of the action based on the intrinsic nature of the action (that is, often reflecting greater concern for individual rights and duties3). The dilemma between these two principles plays a prominent role in law and policy-making decisions, ranging from decisions of health budget allocations4 to dilemmas related to self-driving vehicles5. This inherent conflict is well illustrated by the so-called trolley problem, which has long interested both philosophers and psychologists. One version of the dilemma is presented as follows:6

You are a railway controller. There is a runaway trolley barrelling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five workmen. The trolley is headed straight for them, and they will be killed if nothing is done. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a side track and you can save the five workmen on the main track. You notice that there are two workmen on the side track. So there will be two workmen who will be killed if you pull the lever and change the tracks, but the five workmen on the main track will be saved. Is it morally acceptable for you to pull the lever?

A deontological decision-maker would argue that pulling the lever is morally unacceptable, as it would be murder. (Note that deontological principles are often more complicated than this. Some of the deontological rules would allow for killing in this situation. The terms ‘deontological’ and ‘utilitarian/consequentialist’ are labels we use to refer to certain responses.) On the other hand, utilitarianism would suggest that it is morally acceptable to pull the lever, as it would maximize the number of lives saved.

In an alternative version of the dilemma, one has to push a man off a footbridge in front of the trolley (the ‘footbridge’ scenario). This man will die but will stop the trolley, and the five people in the way of the trolley will be saved. Interestingly, people are less likely to make a decision consistent with utilitarian perspectives in the footbridge scenario compared with the standard switch scenario. (We call these ‘utilitarian’ responses, but the fact that these decisions are consistent with utilitarianism does not indicate that people gave them out of utilitarian principles. The same is true for ‘deontological’ responses7,8.) The difference between the utilitarian response rate in those scenarios became the basis of investigations of many influential cognitive theories in the field of moral judgement3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. The fact that people respond differently to the two trolley dilemmas was proposed to be explained by people’s adherence to the so-called doctrine of double effect6,9. A simple version of this doctrine is that harm is permissible as an unintentional side-effect of a good result. This doctrine is the basis of many policies in several countries all around the world concerning issues such as abortion6, euthanasia14, international armed conflict regulations15,16 and even international business ethics17. According to this doctrine, it is morally impermissible to bomb civilians to win a war, even if ending the war would eventually save more lives. However, if civilians die in a bombing of a nearby weapons factory as a side-effect, the bombing is morally acceptable. The way people perceive or act on these moral rules can influence the policies that are accepted or even followed, as we can already see in the case of driverless cars, which sometimes have to decide between sacrificing their own passengers and saving one or more pedestrians5.

However, Greene et al.18 and Cushman et al.9 argued that the difference in utilitarian response rates cannot simply be explained by the doctrine of double effect. Greene et al. presented evidence for the interaction of the intention of harm (that is, harm as means or side-effect, referring to the doctrine of double effect) and personal force (that is, whether or not the agent had to use personal effort to kill the victim and save more people) on moral acceptability ratings. More concretely, people were less likely to judge sacrificing one person to save more people as morally acceptable when they had to use their personal force to kill the person and the death of this person was required to save more people (this is what is meant by intending the harm). Hence, they concluded that people are more sensitive to the doctrine of double effect when they have to use their own physical force. Despite some exceptions19,20, most of the evidence for this conclusion comes from samples from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic (WEIRD)21 societies, leaving the question open of whether these effects are psychologically universal or culture specific.

This study tests three cross-cultural hypotheses:

-

(1)

The effects of personal force on moral judgements are culturally universal.

-

(2)

The interactional effect of personal force and intention on moral judgements is culturally universal.

-

(3)

Collectivism–individualism has a moderating effect on the degree to which personal force and intention affect moral judgements in such a way that their effect is stronger in more collectivistic cultures.

The first and second hypotheses, that the effects of personal force and intention on moral judgements are culturally universal, come from their relatedness to interpersonal violence. People seem to exhibit a general tendency to avoid causing violent harms (for example, murder)22,23, and they are more likely to perceive actions as violent or harmful when they are supposed to use personal force or intention3. As a result, people are more likely to behave in a deontological way when personal force or intention is present in the dilemma. As all cultures regulate interpersonal violence24, we expected to find that both intention and personal force, as well as their interaction, have an effect on moral judgements across cultures. The literature seems to be in accordance with these hypotheses. For example, Chinese25,26,27 and Russian21 participants responded similarly to moral dilemmas as people from the United States and Western Europe, and even small-scale societies tended to be susceptible to the effect of intention19,20.

Even though we anticipated that the effect of personal force and intention would emerge universally across cultures, we nonetheless expected cultural differences to moderate these effects. The effect of personal force on moral judgement has been attributed to emotional processes9,28,29,30, specifically social emotions (such as guilt, shame or regret)31,30. The potential use of personal force makes people feel guilt or shame before making a decision and, therefore, rating actions that use personal force as morally less acceptable. There is a convincing argument that these social emotions are universal32,33,34, despite some cultural variation in their intensity and the social contexts in which they are experienced32,33,34. It has been argued that shame and guilt are more important in interdependent, collectivistic cultures (as their function is argued to be linked to social control). People living in East Asian countries have reported experiencing these emotions more frequently and more intensely32,33,34. Other findings suggest that it is anxiety that mediates the effect of intention and personal force28, but anxiety (social anxiety in particular) has also been positively associated with collectivism35, pointing to the same direction. Hence, we hypothesized that people living in collectivistic cultures would judge actions that involve personal force and intention as morally less acceptable than people in individualistic cultures. Utilitarian responding in moral dilemma judgements has also been associated with low levels of empathic concern36, and people living in collectivistic cultures have been suggested to exhibit higher levels of empathic concern37,38. Hence, we predicted that individualism–collectivism would also have an effect on utilitarian responding: collectivists would be less utilitarian in general, because of their higher levels of empathic concern.

In addition to testing our confirmatory hypotheses, we also collected a number of additional country-level as well as individual measures for exploratory purposes. These measures, such as economic status39, individual-level individualism–collectivism39 and religiosity40, have been previously shown to be related to moral judgement. We also administered an alternative measure of utilitarian responding41,42,43,44.

The present investigation is crucial for advancing the field for the following reasons:

-

1.

The original article has been very influential (714 citations so far), but replicability has not been established yet.

-

2.

Our knowledge on the cultural universality of the effect of personal force and intention in moral judgements is scarce.

-

3.

The resulting database (with many types of trolley problems and additional measures) could assist and guide future research and applications on moral thinking.

Overview

In the first part of our study, we tested the universality of the role of personal force in moral judgements with a direct replication of study 1 conducted by Greene et al. In their study, the authors found evidence that the application of personal force decreases the moral acceptability of the utilitarian action (hypotheses 1a and 1b). In the second part, we tested the universality of the interactional effect of personal force and intention on moral dilemma judgements, by replicating study 2 of Greene et al. (hypotheses 2a and 2b) with partially different moral dilemmas. Furthermore, we tested our hypothesis that collectivism moderates the effect of intention and personal force (hypothesis 3). In addition, we collected various additional measures for exploratory purposes.

Results

We collected data from 27,502 participants from 45 countries. Due to our exclusion criteria, we had to exclude 80.6% of the sample from the main analysis (see Table 1 for the various exclusion criteria). Note that, as we registered, we conducted the analysis without excluding the data of the participants who were familiar with the trolley problem (36.2% exclusions), and we also conducted a post hoc explorative analysis in which we applied no exclusion criteria. All participants were presented with two moral dilemmas that were equivalent in structure but different in wording: trolley dilemmas and speedboat dilemmas. The former described a situation involving a trolley and people on the tracks, while the latter described a situation with people on a speedboat and others drowning in the sea. In study 1, we tested the effect of personal force on moral dilemma judgements (hypotheses 1a and 1b), while in study 2, we tested the interaction effect between personal force and intention (hypothesis 2a, 2b and 3).

The effect of personal force

The findings are presented in Fig. 1. To test the effect of personal force on moral judgement, we used one-sided t tests. Consistent with our preregistration, we analysed only the continuous acceptability ratings (on a scale from 1 to 9) but not the binary choices. In each cultural cluster, we found at least strong evidence (Bayes factor (BF10) > 10) of an effect of personal force on moral judgement, which implies that the effect is culturally universal. The results indicate that, when personal force is seen to be necessary to save more lives, people are less likely to favourably judge a consequentialist outcome (that is, save more people). The results remained robust across dilemma contexts (that is, the trolley or speedboat version) and when including participants who were very familiar with these trolley problem-type scenarios. Therefore, our results replicated the findings of Greene et al. in the original cultural setting (H1a) and in the Southern and Eastern cultural clusters (H1b). The statistical results are summarised in Table 2.

a–d, Results for trolley (a,b) and speedboat dilemmas (c,d) with all exclusion criteria applied (a,c) or including familiar participants (b,d). Error bars show 95% CI around the mean. Scale ranges from 1 (completely unacceptable) to 9 (completely acceptable). Trolley problem: n = 1,569 when all exclusion criteria applied, and n = 3,524 when familiarity exclusion not applied. Speedboat dilemma: n = 1,426 when all exclusion criteria applied, and n = 3,295 when familiarity exclusion not applied.

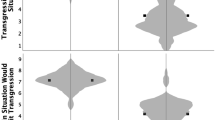

The interaction effect of personal force and intention

Figure 2 shows that, when we applied all the exclusion criteria, we found strong evidence in the Western cluster (hypothesis 2a) for the interaction between personal force and intention (BF10 = 1.5 × 1011), but moderate inconclusive evidence in the Southern (BF10 = 9.4) and weak, inconclusive evidence in the Eastern clusters (BF10 = 0.6) (hypothesis 2b). More concretely, in the Western cluster, participants judged the acceptability of consequentialist decisions much lower when both personal force and intention had to be applied (that is, the personal force effect was numerically greater when intention also had to be applied). When we included participants who were familiar with the trolley dilemma, we still found strong evidence in the Western cluster (BF10 = 1.28 × 1030) and, interestingly, we also found strong evidence in the Southern cluster (BF10 = 3.1 × 106), but the evidence remained weak and inconclusive in the Eastern cluster (BF10 = 2.9). Although in the preregistration we expected the effect sizes to be smaller when participants familiar with the trolley problem were included, we observed the direct opposite: when including data of participants familiar with the trolley problem, we found either equivalent or larger effect sizes in all cultural clusters. Notably, the size of the effect almost doubled in the Southern cluster when running the analysis on the sample with familiar and unfamiliar participants included (ηp2 increased from 0.014 to 0.026). All statistical results are presented in Table 3.

a–d, Results for trolley (a,b) and speedboat dilemmas (c,d) with all exclusion criteria applied (a,c) and including familiar participants (b,d). Error bars represent 95% CI. Scale ranged from 1 (completely unacceptable) to 9 (completely acceptable). Trolley problem: n = 3,984 when all exclusion criteria applied, and n = 9,844 when familiarity exclusion not applied. Speedboat dilemma, n = 3,513 when all exclusion criteria applied, and n = 9,006 when familiarity exclusion not applied.

On the speedboat dilemmas, we found strong evidence for the interaction in the Western cluster, regardless of the familiarity exclusion (BFall exclusions = 222, BFwith familiar = 4.8 × 107). However, we found inconclusive evidence in the Eastern and Southern clusters, both before (BFEastern = 0.4, BFSouthern = 0.4) and after (BFEastern = 0.4; BFSouthern = 1.1) familiarity exclusions. Although our results were consistent in the Western and Eastern clusters for both the speedboat and trolley dilemmas, there was a divergence in the Southern cluster. Specifically, we found strong evidence only for the interaction in the Southern cluster when we included familiar participants in the analysis. In general, in all clusters, the observed effect sizes were smaller on the speedboat than on the trolley dilemma.

In summary, we conclude that we fully replicated the findings of Greene et al. with respect to the interaction of personal force and intention in the Western cluster (hypothesis 2a) regardless of dilemma context or exclusion criteria. However, the evidence was inconclusive for all analyses of the Eastern cluster. In the Southern cluster, the conclusion is both context dependent (that is, the effect was only detectable in the trolley dilemma) and sensitive to exclusion criteria (that is, the effect was only detectable when familiar participants were included).

To explore whether our results were sensitive to our choice of priors in the Bayesian analysis, we computed robustness regions (RRs) that indicate the region of priors within which our inference would remain unchanged. The width of this region shows how robust our inferences are to our selection of priors. The RRs were generally wide for all statistical tests (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that our results were not sensitive to our choices of prior. Thus, we would arrive at the same conclusions with any possible prior within the realistic range. One exception to this finding where the final conclusion was prior dependent can be found in the analysis of the Southern cluster in study 2. Specifically, if the scale of the prior distribution had been r = 0.21 or higher (instead of r = 0.19), we could have concluded that there was strong evidence for the effect (instead of saying that the test is inconclusive). Here, we would like to stress that we did not reach our registered sample size in this cluster for study 2 (we registered that, for 95% power, we would need 1,800 participants in each cluster after exclusions, of which we only reached 323 in the Eastern and 690 in the Southern, but we did reach the desired n in the Western cluster with 2,971 participants; see Methods section for details on sample size estimation). This could explain why our results did not reach our evidence thresholds and remained inconclusive.

Cultural correlates

To test the ‘effects’ of cultural variables, we used linear mixed models predicting moral acceptability ratings from different cultural variables with the random intercept of countries. We tested all five cultural variables one by one (that is, country-level collectivism, and the four individual-level measures of horizontal and vertical collectivism–individualism), in separate linear models on the data with and without familiarity exclusion.

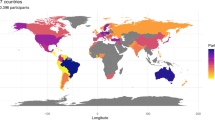

Hypothesis 3 stated that we expected a three-way interaction between country-level collectivism, intention and personal force. We first tested this hypothesis on the data with familiarity exclusion applied (see Table 4 for the statistical results and Fig. 3 for a graphical representation of the findings). The results of the country-level collectivism scale were inconclusive (trolley: BF10 = 1.2; speedboat: BF10 = 0.9). When analysing the individual-level measures of horizontal and vertical collectivism–individualism, all results were inconclusive. We conducted the same analysis on the sample but this time including participants who were familiar with these types of moral dilemmas, but the results were still inconclusive (trolley: BF10 = 2.2; speedboat: BF10 = 0.7). Analysing the individual-level individualism–collectivism measures, we found inconclusive evidence in all the scales. In the Introduction (stage 1), we also hypothesized that country-level collectivism would be associated with decreased overall acceptability of the utilitarian option. This hypothesis was not included in the registered analysis plan. Nevertheless, we added this analysis to the Supplementary Analysis Section 3. In short, we found no evidence for the association between country-level collectivism and moral acceptability rates. Interestingly, nevertheless, we found strong evidence for a positive correlation between vertical individualism and moral acceptability ratings.

a,b, Correlation between country-level collectivism and the η2 effect size of the interaction between personal force and intention with all exclusion criteria applied (a) and including familiar participants (b) on the trolley problem. The size of the circles indicates the size of the sample in a given country. The blue line is the weighted regression. MYS, Malaysia; CHN, China; IND, India; THA, Thailand; MKD, Macedonia; PAK, Pakistan; IRN, Iran; JPN, Japan; GBR, Great Britain; FRA, France; HUN, Hungary; COL, Colombia; ARG, Argentina; TUR, Turkey; ECU, Ecuador; CHL, Chile; PER, Peru; PHL, Philippines; MEX, Mexico; USA, United States; SRB, Serbia; RUS, Russia; DEU, Germany; CAN, Canada; POL, Poland; ITA, Italy; KAZ, Kazakhstan; NZL, New Zealand; NLD, The Netherlands; ROU, Romania; BRA, Brazil; SGP, Singapore; ESP, Spain; AUS, Australia; BGR, Bulgaria; CHE, Switzerland.

We conducted the same analysis on the speedboat dilemmas. Table 4 and Fig. 4 present the findings. Regardless of the familiarity exclusion criteria, we found inconclusive results in all cases.

a,b, Correlation between country-level collectivism and the η2 effect size of the interaction between personal force and intention with all exclusion criteria applied (a) and including familiar participants (b) on the speedboat problem. The size of the circles indicates the size of the sample in a given country. The blue line is the weighted regression. MYS, Malaysia; CHN, China; IND, India; THA, Thailand; MKD, Macedonia; PAK, Pakistan; IRN, Iran; JPN, Japan; GBR, Great Britain; FRA, France; HUN, Hungary; COL, Colombia; ARG, Argentina; TUR, Turkey; ECU, Ecuador; CHL, Chile; PER, Peru; PHL, Philippines; MEX, Mexico; USA, United States; SRB, Serbia; RUS, Russia; DEU, Germany; CAN, Canada; POL, Poland; ITA, Italy; KAZ, Kazakhstan; NZL, New Zealand; NLD, The Netherlands; ROU, Romania; BRA, Brazil; SGP, Singapore; ESP, Spain; AUS, Australia; BGR, Bulgaria; CHE, Switzerland..

Exploratory analysis

The effect of intention

We registered that we would test the main effect of intention by comparing the standard switch (no intention) and footbridge switch (intention) dilemmas. We found strong evidence in each cultural cluster and in each dilemma type for the effect of intention (BF10 > 10). Importantly, the effect of intention remained unchanged even when we included participants who were familiar with moral dilemmas in the sample (BF10 > 10). Tables 5 and 6 summarize the findings. As registered, we also tested the effect of physical force on moral judgement. In accordance with Greene et al., we found no evidence for this effect. See details in Supplementary Analysis Section 2.1.

No exclusion analysis (post hoc)

As the exclusion rate in the above analyses was very high (81%), we explored our results while applying no exclusion criteria (including all participants). In study 1, we found strong evidence for the individual effects of personal force and intention, in each of the three cultural clusters, in both the speedboat and the trolley dilemmas, just as in our main analyses (see Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2 for the detailed results and data distribution).

For study 2, Extended Data Fig. 3 summarizes the statistical findings. Overall, we can conclude that almost all of our results regarding the effects of personal force and its interaction with intention are not sensitive to our exclusion. Only in the case of the Eastern cluster can we see a difference: without applying exclusions, strong evidence can be found for the effect of personal force and intention in the trolley dilemma, whereas otherwise, we find inconclusive evidence. Here, we can only speculate whether the increased strength of evidence is due to the increased number of participants. The analysis on the speedboat dilemmas yielded the same results with and without exclusions: inconclusive evidence in the Eastern and Southern clusters, and strong evidence in the Western cluster (see Extended Data Fig. 4 for the findings of study 2). Thus, it appears that applying such strong exclusion criteria did not strengthen the replication effort nor substantially alter the inferences we draw about the replicability of the effect of force and intention.

We also conducted the cultural analysis without applying any exclusion criteria, finding that all of the results were inconclusive, with one exception. In the speedboat dilemma, we found moderate evidence that country-level collectivism is positively associated with the interaction of personal force and intention (in line with our hypothesis; BF10 = 5.1; same test for the trolley dilemma: BF10 = 2.8). We also found moderate evidence (BF10 = 9.8) that, in the trolley dilemma, the interaction between personal force and intention is positively associated with individual-level horizontal collectivism: being higher on horizontal collectivism means a heightened personal force and intention interaction effect size (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6; the same test in the speedboat dilemma was inconclusive: BF10 = 0.54). Thus, for the moderation of the effect by country-level collectivism, the strict exclusion criteria may have hurt our ability to detect these effects. Although these results appear in line with our prior hypothesis, this analysis was only exploratory, not registered a priori, and hence should only be interpreted with caution.

As we registered, we added a figure showing the distribution of responses of both subscales of the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale for each country cluster, and also reported means and 95% CI, as registered. Moreover, we also added a post hoc analysis correlating each subscale of the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale with the moral acceptability ratings of the moral dilemmas. We found that moral acceptability ratings correlate higher with the instrumental harm subscale (r = 0.40–0.45) than with the impartial beneficence subscale (r = 0.05–0.20), with this latter correlation exhibiting somewhat larger cultural variations. Details can be found in Supplementary Analysis Section 2.4.

Discussion

For centuries, philosophers and psychologists have explored the determinants of moral judgements. Moral dilemmas that force life-and-death decisions help us to explore which norms and psychological processes drive our moral preferences. Initially, researchers thought45,46 that people are simply susceptible to the doctrine of double effects when making moral judgements, that is, that harm is permissible if it occurs as an unintentional side-effect of an overall good outcome. Greene et al.18, however, showed that the role of using physical force to kill one (and save more) influenced moral judgements even more than did the intentionality of an action.

In this research, we replicated the design of Greene et al.18 using a culturally diverse sample across 45 countries to test the universality of their results. Overall, our results support the proposition that the effect of personal force on moral judgements is likely culturally universal. This finding makes it plausible that the personal force effect is influenced by basic cognitive or emotional processes that are universal for humans and independent of culture. Our findings regarding the interaction between personal force and intention were more mixed. We found strong evidence for the interaction of personal force and intention among participants coming from Western countries regardless of familiarity and dilemma context (trolley or speedboat), fully replicating the results of Greene et al.18. However, the evidence was inconclusive among participants from Eastern countries in all cases. Additionally, this interaction result was mixed for participants from countries in the Southern cluster. We only found strong enough evidence when people familiar with these dilemmas were included in the sample and only for the trolley (not speedboat) dilemma.

Our general observation is that the size of the interaction was smaller on the speedboat dilemmas in every cultural cluster. It is yet unclear whether this effect is caused by some deep-seated (and unknown) differences between the two dilemmas (for example, participants experiencing smaller emotional engagement in the speedboat dilemmas that changes response patterns) or by some unintended experimental confound (for example, an effect of the order of presentation of the dilemmas). Furthermore, in the Eastern and Southern clusters, more participants found the dilemmas confusing than in the Western cluster (Table 2). The increased confusion rates might have played a role in the fact that we found no evidence for the personal force and intention interaction in the speedboat dilemmas. Participants from the Southern and Eastern clusters might have struggled to follow some versions of the speedboat dilemma, as it was originally written for US participants.

Furthermore, we hypothesized that collectivism would enhance the effect of personal force and intention. This prediction was based on the notion that collectivism increases the sensitivity to certain emotions which mediate these effects. We found no evidence for this hypothesis when we executed our preregistered analysis plan. However, in the exploratory analysis (with no exclusion criteria applied), we found some moderate evidence for the association of country-level collectivism in the speedboat dilemma, and individual-level horizontal collectivism in the trolley dilemma with the interactional effect of personal force and intention. Since this analysis was not preregistered, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

The interaction between intention and personal force was sensitive to whether we included participants familiar with moral dilemmas. In the Southern cluster, this led to inconclusive evidence regarding the trolley problem, but contrary to our expectations, the size of all of the interaction effects was larger when we included familiar participants in the analysis. This increase could be due to at least two reasons: (1) familiarity is not the main reason behind the change in response patterns: familiarity correlates with an as-yet-unknown underlying variable, which induces a selection bias (for example, educational background), and (2) familiarity is the main reason behind the change in response patterns: for example, being familiar with the trolley problem might have caused people to exhibit a lower emotional response to the problem or caused them to apply different reasoning that ended up affecting their responses. Our results cannot differentiate between the above-described explanations (which are not necessarily mutually exclusive).

Although we found no strong evidence for the association between collectivism–individualism and the effects of personal force and intention, future research should test for other cultural variations. There are a number of interesting candidates that we did not examine, including cultural tightness47 and social mobility48. Our database provides opportunities to the field to examine different aspects and cultural moderators of moral judgement.

This research has a number of limitations that future work will need to address. Although we call the personal force effect ‘universal’, it is only universal to the cultures we tested. This puts a limit to the universality of the effects: we did not (nor did we intend to) reach small-scale hunter–gatherer societies, for example. Moreover, while our sample was more diverse and less WEIRD than that of Greene et al.’s research, it consisted of mostly educated individuals from younger age groups with internet access, raising similar concerns (for example, still Educated and Industrialized, and possibly Rich, though not strictly Western or Democratic). Secondly, the data collection was conducted before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which could have affected the participants’ responding behaviour in some way (for example, moral fatigue). Finally, 81% of the sample was not entered into the main confirmatory analyses because of our exclusion criteria, which might have resulted in unintended selection biases. For example, it is possible that more educated participants were more likely to be excluded because of being familiar with moral dilemmas from college. It is also possible that people with less working memory capacity or poor text comprehension abilities were more likely to be excluded due to the stringent attention checks. This is why we included an exploratory analysis in which we analysed data from all of our participants, without applying any exclusions. Our results on the full sample (with no exclusion criteria applied) supported our previous conclusions (drawn based on the data with exclusions) except in the cultural analysis, in which we found strong evidence for cultural variations only when no data were excluded. Thus, future work, especially replication work, should take caution when applying stringent exclusion criteria as it may be entirely unnecessary and even hurt the discovery of new effects.

Another limitation of our study might come from the fact that we used a single continuous measure of deontological–utilitarian tendencies. Although common in the field, such an approach has been criticized for being overly simplistic and not being able to pick up on more complex response patterns49,50. For example, maximizing outcome and rejecting harm are not necessarily symmetrical (as our continuous measure suggests). Hence, an interesting direction for future research could be to identify whether personal force and intention increase reliance on deontological rules or decrease reliance on consequentialist thinking. Methodological approaches, such as process dissociation, are promising in this regard44.

Conclusion

With this replication study, we present empirical results about how people around the world make judgements in moral dilemmas that have long interested moral philosophers and psychologists. Empirical studies in this field have been conducted mostly on WEIRD samples, with little attention paid to cultural universality and variations. Our research allows us to avoid some important selection biases by having participants take the survey in their native language from 45 countries. The shared dataset should allow the assessment of different effects on moral dilemma judgements, such as religion or second-language effects.

Overall, we found (1) the negative main effects of personal force and intention on moral dilemma judgements are universal; (2) the interaction between intention and personal force was replicated in the Southern and Western clusters, finding people are less likely to support sacrificing one person’s life for the sake of saving the lives of several others, if they have both to intentionally engage in an action to do this and to use personal force; and (3) this interaction is not associated strongly with individual or country-level collectivism–individualism measures.

Methods

Participants

A large, culturally and demographically diverse sample of participants was recruited from collaborating laboratories through the Psychological Science Accelerator51. The data collection team originally proposed to include 146 laboratories from 52 countries. All of these participating laboratories obtained institutional review board approval (verified before the last round of stage 1 submission). Combined, these laboratories committed to collect a minimum of 18,637 participants. More laboratories were expected to be recruited before data collection commenced. Each laboratory recruited participants for the study by sending out the survey link along with the consent form to their participant pool or online platforms (such as MTurk), or testing them in the research laboratory. Due to some dropouts, the data collection team included 140 laboratories from 45 countries. Eligibility for participation was based on age (≥18 years) and being a native speaker of the language of the test (more details on this criterion in Controlling for possible confounds section). Data were collected either from local university participant pools or via data collection platforms (for example, MTurk). Altogether, 41,090 participants started our survey, and 27,502 finished it, whose data were analysed (17,961 female, 7,956 male, mean age 26.0 years, s.d. 10.3 years; study 1: 7,744 participants, 4,329 female, 2,487 male, mean age 26.8 years, s.d. 11.1 years; study 2: 19,340 participants, 13,632 female, 5,469 male, mean age 25.8 years, s.d. 9.98 years).

We did not collect any identifiable private data during the project that can be linked to individual survey responses. Each laboratory ascertained the agreement of the local institutional ethical review board with the proposed data collection. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board approvals are available on our OSF project page (https://osf.io/j6kte/). Participants had to give informed consent before starting the experiment. Only participants recruited through Mturk or Prolific received monetary compensation.

Materials

Moral dilemmas

We used a total of six trolley dilemmas: footbridge switch, standard footbridge, footbridge pole, loop, obstacle collide (taken from Greene et al.) and standard switch. All the materials are provided in Supplementary Methods Sections 1–3. Each of these scenarios represents a different condition. For example, in the standard footbridge scenario, both intention and personal force are required to push the man off the bridge. As in the original experiments, every participant was assigned to only one of these dilemmas. The problems were accompanied by a drawn sketch to aid understanding. Following the original procedure, after presenting each problem, participants were asked whether the described action (for example, pushing the man to save five people) is morally acceptable or not (yes–no response). After this judgement, participants were asked to indicate on a numbered Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely unacceptable) to 9 (completely acceptable), the extent to which they think that the given action is morally acceptable. Next, participants were asked to type the justification of their decision in an open question format. After participants were presented with the first trolley dilemma, they were presented with a second dilemma from the same condition, without drawn sketches. For the second dilemma, we used the speedboat dilemmas. These dilemmas are taken from studies 1b and 2b of Greene et al. and can be found in Supplementary Methods Section 1, with the exception of the dilemmas in the obstacle collide and standard footbridge conditions, which were provided by Joshua Greene during the review of the study. The order of dilemma presentation was fixed, so that the trolley version was always presented first. Study 1 was run before study 2, but participants were randomly assigned to one of the dilemmas within each study.

Additional measures

Although an exploration of individual-level factors associated with moral thinking is not the aim of the present research, to enrich our database for future studies and secondary analyses, we expanded our survey with additional individual-level measures: (1) total yearly household income, (2) place of living (urban or rural area), (3) position on the four-dimensional Individualism–Collectivism Scale38 (16 items) for disentangling cultural differences in participants’ responses52 and (4) religion (specific religion of the participant, plus one question to measure their level of religiosity: “On a scale from 1 to 10, how religious are you?”). Furthermore, we included the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale32 (nine items). Following these questions, the participants’ level of education, age and sex were also recorded. We also recorded the participants’ country of origin and whether the participant came from an immigrant background.

Procedure

The experiment was administered by using a centralized online survey that participants could answer remotely or in the laboratory. We used the original instructions of Greene et al., as presented in Supplementary Methods Section 1. After responding to the dilemmas, participants were asked to answer three questions: (1) a measure of careless responding (question about the specifics of the trolley scenario), (2) whether they found the material confusing and (3) whether they found the description of the problem realistic. After these questions, participants were directed to our series of questionnaires: the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale, followed by the Individualism–Collectivism Scale and the measures of religion. Next, we administered the demographic questions (income, place of living, country of origin, immigrant background, level of education, age and sex). Afterwards, we asked three further questions to measure careless responses, participants’ familiarity with research questions and finally for further comments or any technical problems experienced.

Controlling for possible confounds

To avoid second-language effects on moral judgement53, only native speakers of the language of the experiment could participate. To ensure this, we asked participants to indicate their native language(s). Bilingual participants could choose their preferred language. The data from anyone with a native language different from the language of the survey were removed from the analyses.

Following Greene et al.’s procedure, data from participants who reported that they found the material confusing were excluded from the analyses. Data from participants who reported having experienced technical problems during the experiment were also excluded from all analyses. To avoid careless responses, we added three bogus items at the end of the survey. We asked participants very basic questions (for example, “I was born on February 30th.”) to which incorrect answering indicates careless responding54. We excluded data from participants who gave an incorrect response to any of these questions. Moreover, we introduced two additional questions (presented immediately after the moral dilemmas), asking participants about the specifics of the trolley and speedboat scenarios that they had been presented with, to test whether they had paid attention when reading the scenarios (referred to as attention check in the later test). Specifically, participants were asked to select the option which most accurately described the situation that they had been presented with. Each option described the nature of the physical action that was the key manipulation in the experiment. Because attention to the trolley and speedboat dilemmas was measured by different questions, when analysing the responses, we excluded the data for the correspondingly failed attention check question. For example, people who gave a correct response on the trolley but not on the speedboat attention check question were included when analysing the trolley dilemma but excluded when analysing the speedboat version.

As moral dilemmas are becoming more and more common in psychological research and in summaries of this research in popular media and culture and teaching, it is possible that some participants may have previous knowledge of these dilemmas, which may affect their responses. To address this potential problem, at the end of the experiment, participants were asked the following question: “Before this experiment, were you familiar with moral dilemmas of this kind, in which you can save more people by causing the death of one person?” Answers were given on a rating scale from 1 (absolutely not familiar) to 5 (absolutely familiar). Familiarity with the trolley problem or such moral dilemmas (participants who responded with 4 or 5 on this scale) was used as a further exclusion criterion. Additionally, participating laboratories were asked to avoid recruiting philosophers or philosophy students because they are likely to have heard about trolley problems, and we wanted to minimize the number of participants to be excluded following data collection.

Notable deviations between this study and the design of Greene et al.

Besides the multinational data collection that forms the crux of our project, the first important methodological difference between this study and the original study is that the original study was conducted by paper and pencil, whereas we administered the experiment online. Of note, recent research found no evidence for a difference between the behaviour of participants who took part in the experiment online versus those who took part in the experiment in a laboratory. We also added one change in the introduction of the experiment (see Supplementary Methods Section 1): participants were not given the opportunity to ask the researcher any questions before the experiment (as the experiment can be administered online, they did not have the opportunity to do so).

The second important change in this experiment is that participants were presented with two moral dilemmas in one condition, instead of one. These additional dilemmas will be analysed separately, as they were in the original experiment. The third difference is that, for study 2, we used moral dilemmas different from those that were used by Greene et al. The standard switch and footbridge dilemmas were used instead of the loop weight and obstacle push dilemmas, respectively. These dilemmas are not different from the ones used by Greene et al. in their structural characteristics, only on surface characteristics. That is, in the standard switch, the harm is unintended and no personal force is required, while in the standard footbridge dilemma, the harm is intended and requires personal force. By including the standard switch and standard footbridge scenarios instead of the original ones, we gain further insight into the data. Imagine, for example, that the personal force effect does not replicate in one of the cultural clusters. One explanation for this is that people are simply not sensitive to the effect of personal force in that cluster. However, it might also be the case that utilitarian response rates to similar dilemmas increase over time55. If so, we should see that the replicated difference between the standard footbridge and switch dilemmas is shrinking or disappeared. Furthermore, by comparing the standard footbridge with the footbridge pole dilemma, we can test the effect of physical contact, and by comparing the standard switch case with the footbridge switch case, confirm the effect of intention.

Finally, in the original experiment, Greene et al. excluded participants who did not manage to suspend disbelief. Nevertheless, as they noted, this had no effect on their results. Thus, we decided that we would not use this exclusion criterion.

Cultural classification of countries

To test the cultural universality hypothesis, a comprehensive cultural classification that encompasses multiple sources of cultural variability is needed. Hence, to assess our first hypothesis on the universality of the effect of personal force and intention on moral judgements, we used the cultural classification of Awad et al.39. On the basis of surveyed moral preferences, they identified three distinct clusters of countries: Eastern, Southern and Western. They argued that this cluster structure is broadly consistent with the alternative but more complex Inglehart–Welzel cultural map38. Therefore, we assigned the countries of our participating labs to these cultural clusters, as listed in Supplementary Methods Section 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Language adaptation

The participating laboratories translated the survey items into the language of the participant pool, following the translation process of the PSA (https://psysciacc.org/translation-process/) detailed below:

-

1.

Translation: The original document is translated from the source to target language by A translators resulting in document version A.

-

2.

Back-translation: Version A is translated back from the target to source language by B translators independently, resulting in version B.

-

3.

Discussion: Version A and B are discussed among translators and the language coordinator, discrepancies in version A and B are detected and solutions are discussed. Version C is created.

-

4.

External readings: Version C is tested on two non-academics fluent in the target language. Members of the fluent group are asked how they perceive and understand the translation. Possible misunderstandings are noted and again discussed as in step 3.

-

5.

Cultural adjustments: Data collection laboratories read the materials and identify any adjustments needed for their local participant sample. Adjustments are discussed with the language coordinator, who makes any necessary changes, resulting in the final version for each site.

Planned analyses

Preregistered analysis

Confirmatory replication analyses

As explained in the introduction, we focused our analyses on the question of the universality of Greene et al.’s two most important claims. We conducted independent analyses in each cultural cluster and report them separately. We preregistered the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: There is an effect of personal force on moral judgement in the Western cluster (replication of the original effect).

Hypothesis 1b: If the effect of personal force is culturally universal, there is an effect of personal force on the moral acceptability ratings (Greene et al., study 1) in the Southern and Eastern cultural clusters as well.

Hypothesis 2a: There is an interaction between personal force and intention (Greene et al., study 2) in the Western cluster (replication of original effects). More specifically, the intention factor is larger when personal force is present compared with when personal force is absent.

Hypothesis 2b: If this effect is culturally universal, there is an effect in the Southern and Eastern cultural clusters as well.

Unlike in the original study, we employed Bayesian analyses to obtain information from our data concerning the strength of evidence for the null and alternative hypotheses. The BF indicates the relative evidence provided by the data comparing two hypotheses56. Regarding the threshold of strong Bayesian evidence, we followed the recommendations of ref. 57 and set the decision threshold of BF10 to >10 for H1 and <1/10 for H0. We used informed priors for the alternative model: a one-tailed Cauchy distribution with a mode of zero and a scale of r = 0.26 (hypotheses 1a and 1b) and r = 0.19 (hypotheses 2a and 2b) on the standardized effect size using the BayesFactor package58 in R for the analysis. These priors are based on the effect sizes that we expect to find as explained below in the sample size estimation section. We implemented all of our analyses with the R statistical software59.

To test hypotheses 1a and 1b, we compared the moral acceptability ratings given on the footbridge switch problem and footbridge pole dilemma, with the moral acceptability rating of the footbridge switch dilemma expected to be higher. More concretely, we performed three one-sided Bayesian t tests with the same comparison in each cultural group. For each cultural cluster, we would conclude that we replicated the original effect if BF10 > 10, we would conclude that we found a null effect if BF10 < 1/10 and we would conclude that the results are inconclusive if we find a BF10 in between these values (see below for a justification of these thresholds).

To test hypotheses 2a and 2b, we tested the interaction of personal force and intention in each cultural cluster, separately. We conducted Bayesian linear regression analysis in each cultural cluster. The BF of interest is defined as the quotient of the model including the interaction and two main effects (numerator) and the model including only the two main effects (denominator). For each cultural group, we would conclude that we replicated the original effect if the BF of the interaction (BF10) > 10, we would conclude that we found a null effect if BF10 < 1/10 and we would conclude that the results are inconclusive if we find a BF10 between these values (see below for a justification of these thresholds). To further understand the direction of the interaction, we plot the results in each cultural cluster. To conclude the replication of the original effect, we should find that the intention effect is higher in the personal force condition than in the condition with no personal force.

Note that we conducted and reported the frequentist version of the proposed analysis (for example, t tests for each hypothesis, for each cultural class) for the sake of comparability of the original and our results. Nevertheless, we regarded the results of our Bayesian analyses as the basis of our statistical inference. Although we registered that the frequentist statistics would only be added as supplementary material, we added it to the main text for easier comparability. No inference was drawn from the frequentist statistics.

Test assumptions for the statistical tests (t tests and linear regressions) were assumed to hold true, but they were not formally tested.

Robustness analyses

To probe the robustness of our conclusions to the scaling factor of the Cauchy distribution used as the prior of H1, we report RRs for each BF. RRs are notated as min–max, where min indicates the smallest and max indicates the largest scaling factor that would lead us to the same conclusion as the originally chosen scaling factor60.

Sampling plan and stopping rule

As the data were planned to be collected globally, our knowledge was insufficient concerning the noise of the measurement and the rate of exclusion in the various samples, which were needed for accurate sample size estimation. For this reason, we proposed a sequential data acquisition. That is, first, to launch study 1 (hypotheses 1a and 1b), and collect data in sequences from 500 participants per cluster per condition, from 3,000 participants altogether (after all exclusions), then to stop data collection after each sequence. At these stops, we would conduct our planned Bayesian analyses. Should the BF reach the preset thresholds in a given cluster, we would stop data collection for that cluster. If, in a cluster, the BF thresholds were not reached, we would continue data collection with 200 additional participants per cluster per condition, then re-analyse the data, repeating this procedure until one of the BF thresholds was reached or the participant pool was exhausted. Note, however, that we deviated from this sampling plan. See Deviations from registration section for details.

Should we not have reached this limit with our planned capacity of ~19,000 participants, we would have extended the data collection to a new semester. In the case that we would have not reached our evidence threshold within 12 months, we would have reported our final results, acknowledging the limited strength of the findings.

We launched study 2 data collection in a given cluster only when the analysis of study 1 was conclusive. In study 2, we conducted the analysis only when we had exhausted our resources.

Sample size estimation

To calculate our needs for data collection, we conducted a rough sample size estimation. Assuming that the original effect size is found in study 1 (d = 0.4), our sample size estimation indicated that we would require 500 participants per condition per cluster (3,000 altogether), while if the original effect size is to be found in study 2 (d = 0.28), our estimation indicated that we would need 1,800 participants per condition per cluster (21,600 altogether for study 2) to obtain 95% power in detecting the effect. A detailed description of the sample size estimation can be found in Supplementary Methods Section 4.

Testing the association between country-level collectivism and the effects of personal force and intention

Our third hypothesis proposed that collectivism increases the effects of personal force and intention. As a measure of country-level individualism and collectivism, we added the collectivism measure from the Cultural Distance WEIRD scale (countries’ differences in terms of individualism from the United States)61 as a continuous variable to our model. We tested whether collectivism interacted with personal force and intention (hypothesis 3), as explained in the introduction. Hypothesis 3 expected to find a three-way interaction between collectivism, intention and personal force, for which we used the dilemmas we used to test hypotheses 2a and 2b. In this analysis, we used a Cauchy distribution with a scale of r = 0.37 (the same as used to test hypotheses 2a and 2b, that is, the test of the interaction) as prior. Should we find evidence for null effect (BF < 1/10) of the interaction of individualism−collectivism, personal force and intention, we would conclude that individualism–collectivism does not moderate the effect of personal force and intention.

Analysis of the additional moral dilemmas

Study 1

As explained above, each participant had to give a response on two moral dilemmas. For study 1 (effect of personal force), we conducted the same analysis on the rest of the moral dilemmas, without the trolley versions, as in the original study (Greene et al., study 1b).

Study 2

We conducted the same analysis (interaction of personal force and intention) on the rest of speedboat dilemmas, without the trolley versions.

Further tests

Effect of physical contact and intention

With this set of items, we were able to assess the effect of physical contact, by comparing the standard footbridge and footbridge pole dilemmas. We also assessed the effect of intention by comparing the standard switch case with the footbridge switch case. These analyses were done in every cluster, and we used Bayesian t tests for these comparisons. We used the same prior that we used for the assessment of the effect of physical force (r = 0.26). This analysis was done separately on the trolley and speedboat dilemmas.

Comparing the standard switch and standard footbridge dilemmas

For the reasons explained earlier, we compared the standard footbridge and standard switch dilemmas, in each cultural cluster. For this, we conducted a Bayesian t test, with the same prior previously used for the assessment of the effect of physical force (d = 0.26). This analysis was done separately for the trolley and speedboat dilemmas.

Oxford Utilitarianism Scale

We computed a figure showing the response distribution of each subscale of the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale43 for each cultural cluster to explore potential cultural differences (along with means and 95% CI). The results of this can be found in Supplementary Analysis Section 2.4.

Individual-level horizontal and vertical individualism–collectivism

Triandis and Gelfand49 defined individualistic and collectivistic cultural tendencies using four dimensions: vertical individualism, vertical collectivism, horizontal individualism and horizontal collectivism. We added these continuous measures to our Bayesian linear regression analysis. The predictive power of all four measures was assessed separately.

Including familiar participants

A potentially large number of participants were excluded due to familiarity with the trolley dilemma, and there was a possibility that this exclusion criterion would affect the data from some countries or cultural clusters more than others. To avoid this potential sampling bias, we computed all the above-listed analyses on moral dilemmas (confirmatory and exploratory) on the full sample from which we did not exclude the participants familiar with moral dilemmas. Second, we computed all analyses specifically on data coming from people who were familiar with moral dilemmas, to compare the results of familiar and unfamiliar participants. This latter analysis can be found in Supplementary Analysis Section 2.3 and was limited to the confirmatory hypothesis tests.

Pilot testing

To ascertain that the survey software operated without any technical problems, we planned to conduct a pilot test in which each participating laboratory would have been expected to collect data from ten participants. We would have only assessed the expected functioning of the survey software, without analysing the collected data.

Timeline

We planned to finish data collection within 6 months from stage 1 in-principle acceptance, and we planned to submit our report within 1 month from then.

Deviations from registration

We preregistered that we would collect data from 3,000 participants for study 1 (test of personal force; hypotheses 1a and 1b), after exclusions. Unexpectedly, the exclusion criteria led to 80.6% exclusion of our collected data. At the point when this was realized, it seemed likely that study 1 would exhaust the available sample pool, not leaving capacity for study 2. Therefore, with the agreement of the journal editor, we decided to collect participants for study 1 only until our BF evidence thresholds were reached after all exclusion criteria were applied. This modification allowed us to collect data for study 2 as well.

At the time of this decision, the distribution of responses has been taken into account: We had collected data from 3,473 participants: 1,319 from the Western cluster, 1,762 from the Southern cluster and 392 from the Eastern cluster. After exclusions, 789 participants remained (78% excluded): 296 from the Western cluster (78% excluded), 429 from the Southern cluster (76% excluded) and 64 from the Eastern cluster (84% excluded).

Instead of conducting a pilot study as preregistered, to avoid wasting any (much needed) participants, participating researchers from all laboratories tested the experiment before it was sent out to ensure that there were no grammatical mistakes or functionality problems.

Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 crisis, data collection took 6 months longer than expected (with the agreement of the editor).

Exploratory analysis

During the data pre-processing, we excluded 229 participants from three US-based laboratories as they received a wrong survey link. Furthermore, 13,359 participants started but did not finish the experiment, therefore their data were also dropped from further analyses. These participants did not count towards our final sample and are not part of the data in any way. The final sample used for data analyses consisted of 27,502 participants. Further information on the demographics of our participants can be found in Supplementary Analysis Section 1.

Note that we limited the use of RRs for the confirmatory hypothesis tests.

Protocol registration information

The stage 1 protocol for this Registered Report was accepted in principle on 30 January 2020. The protocol, as accepted by the journal, can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11871324.v1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Collected anonymized raw and processed data are publicly shared on the Github page of the project: https://github.com/marton-balazs-kovacs/trolleyMultilabReplication/tree/master/data.

Code availability

Code for data management and statistical analyses have been written in R and are available at https://github.com/marton-balazs-kovacs/trolleyMultilabReplication.

Change history

06 June 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01403-w

References

Mill, J. S. & Bentham, J. Utilitarianism and Other Essays (Penguin, 1987).

Kant, I. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (Yale Univ. Press, 1785).

Greene, J. D. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap between Us and Them (Penguin, 2013).

London, J. A. How should we model rare disease allocation decisions? Hastings Cent. Rep. 42, 3 (2014).

Bonnefon, J.-F., Shariff, A. & Rahwan, I. The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science 352, 1573–1576 (2016).

Foot, P. The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxf. Rev. 5, 5–15 (1967).

Baron, J. in Moral Inferences (eds Bonnefon, J.-F. & Trémolière, B.) 137–151 (Psychology Press, 2017).

Baron, J. & Gürçay, B. A meta-analysis of response-time tests of the sequential two-systems model of moral judgment. Mem. Cogn. 45, 566–575 (2017).

Cushman, F., Young, L. & Hauser, M. The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgment: testing three principles of harm. Psychol. Sci. 17, 1082–1089 (2006).

Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M. & Cohen, J. D. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 44, 389–400 (2004).

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M. & Cohen, J. D. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293, 2105–2108 (2001).

Gürçay, B. & Baron, J. Challenges for the sequential two-system model of moral judgement. Think. Reason. 23, 49–80 (2017).

Mikhail, J. Universal moral grammar: theory, evidence and the future. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 143–152 (2007).

Boyle, J. Medical ethics and double effect: the case of terminal sedation. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 25, 51–60 (2004).

Gross, M. L. Bioethics and armed conflict: mapping the moral dimensions of medicine and war. Hastings Cent. Rep. 34, 22–30 (2004).

Gross, M. L. Killing civilians intentionally: double effect, reprisal, and necessity in the Middle East. Polit. Sci. Q. 120, 555–579 (2005).

Tully, P. A. The doctrine of double effect and the question of constraints on business decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 58, 51–63 (2005).

Greene, J. D. et al. Pushing moral buttons: the interaction between personal force and intention in moral judgment. Cognition 111, 364–371 (2009).

Barrett, H. C. et al. Small-scale societies exhibit fundamental variation in the role of intentions in moral judgment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4688–4693 (2016).

Abarbanell, L. & Hauser, M. D. Mayan morality: an exploration of permissible harms. Cognition 115, 207–224 (2010).

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world?. Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83 (2010).

Cushman, F. Action, outcome, and value: a dual-system framework for morality. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 17, 273–292 (2013).

Cushman, F., Gray, K., Gaffey, A. & Mendes, W. B. Simulating murder: the aversion to harmful action. Emotion 12, 2 (2012).

Ellsworth, R. M. & Walker, R. S. in The Routledge International Handbook of Biosocial Criminology (eds DeLisi, M. & Vaughn, M. G.) 85–102 (Routledge, 2014).

Gold, N., Colman, A. M., & Pulford, B. D. Cultural differences in responses to real-life and hypothetical trolley problems. Judgm. Decis. Maki. 9, 65–76 (2014).

Ahlenius, H. & Tännsjö, T. Chinese and Westerners respond differently to the trolley dilemmas. J. Cog. Cult. 12, 195–201 (2012).

Moore, A. B., Lee, N. L., Clark, B. A., & Conway, A. R. In defense of the personal/impersonal distinction in moral psychology research: Cross-cultural validation of thedual process model of moral judgment. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 6, 186–195 (2011).

Perkins, A. M. et al. A dose of ruthlessness: interpersonal moral judgment is hardened by the anti-anxiety drug lorazepam. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 612–620 (2013).

Cushman, F., Young, L. & Greene, J. D. in The Oxford Handbook of Moral Psychology (eds Vargas, M. & Doris, J.) 47–71 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Koenigs, M. et al. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature 446, 908–911 (2007).

Szekely, R. D. & Miu, A. C. Incidental emotions in moral dilemmas: the influence of emotion regulation. Cogn. Emot. 29, 64–75 (2015).

Johnson, R. C. et al. Guilt, shame, and adjustment in three cultures. Personal. Individ. Differ. 8, 357–364 (1987).

Tracy, J. L. & Matsumoto, D. The spontaneous expression of pride and shame: evidence for biologically innate nonverbal displays. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11655–11660 (2008).

Scollon, C. N., Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Biswas-Diener, R. Emotions across cultures and methods. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 35, 304–326 (2004).

Heinrichs, N. et al. Cultural differences in perceived social norms and social anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1187–1197 (2006).

Gleichgerrcht, E. & Young, L. Low levels of empathic concern predict utilitarian moral judgment. PLoS ONE 8, e60418 (2013).

Luo, S. et al. Interaction between oxytocin receptor polymorphism and interdependent culture values on human empathy. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1273–1281 (2015).

Cheon, B. K. et al. Cultural influences on neural basis of intergroup empathy. NeuroImage 57, 642–650 (2011).

Awad, E. et al. The Moral Machine experiment. Nature 563, 59–64 (2018).

Koenig, L. B., McGue, M., Krueger, R. F. & Bouchard, T. J. Jr Genetic and environmental influences on religiousness: findings for retrospective and current religiousness ratings. J. Pers. 73, 471–488 (2005).

Kahane, G. On the wrong track: process and content in moral psychology. Mind Lang. 27, 519–545 (2012).

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Farias, M. & Savulescu, J. ‘Utilitarian’ judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition 134, 193–209 (2015).

Kahane, G. et al. Beyond sacrificial harm: a two-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Psychol. Rev. 125, 131–164 (2017).

Conway, P., Goldstein-Greenwood, J., Polacek, D. & Greene, J. D. Sacrificial utilitarian judgments do reflect concern for the greater good: clarification via process dissociation and the judgments of philosophers. Cognition 179, 241–265 (2018).

Hauser, M. Moral Minds: How Nature Designed Our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong.(Ecco/HarperCollins, 2006).

Hauser, M. D., Young, L. & Cushman, F. Reviving Rawls’ linguistic analogy. Moral Psychol. 2, 107–143 (2008).

Gelfand, M. J., Nishii, L. H. & Raver, J. L. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness–looseness. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 1225 (2006).

Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Shariff, A., Rahwan, I. & Bonnefon, J.-F. Universals and variations in moral decisions made in 42 countries by 70,000 participants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 2332–2337 (2020).

Gawronski, B., Armstrong, J., Conway, P., Friesdorf, R. & Hütter, M. Consequences, norms, and generalized inaction in moral dilemmas: the CNI model of moral decision-making. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113, 343 (2017).

Conway, P. & Gawronski, B. Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision making: a process dissociation approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 216 (2013).

Moshontz, H. et al. The Psychological Science Accelerator: advancing psychology through a distributed collaborative network. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1, 501–515 (2018).

Bond, M. H. & van de Vijver, F. J. R. in Culture and Psychology. Cross-Cultural Research Methods in Psychology (eds Matsumoto, D. & van de Vijver, F. J. R.) 75–100 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Costa, A. et al. Your morals depend on language. PLoS ONE 9, e94842 (2014).

Meade, A. W. & Craig, S. B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 17, 437–455 (2012).

Hannikainen, I. R., Machery, E. & Cushman, F. A. Is utilitarian sacrifice becoming more morally permissible? Cognition 170, 95–101 (2018).

Dienes, Z. Using Bayes to get the most out of non-significant results. Front. Psychol. 5, 781 (2014).

Schönbrodt, F. D. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Bayes factor design analysis: planning for compelling evidence. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 128–142 (2018).

Morey, R. D., Rouder, J. N. & Jamil, T. BayesFactor: Computation of Bayes Factors for Common Designs https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BayesFactor/index.html (2015).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018).

Dienes, Z. How do I know what my theory predicts?. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 364–377 (2019).

Muthukrishna, M. et al. Beyond WEIRD psychology: measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychol. Sci. 31, 678–701 (2018).

Acknowledgements

M.A. Vadillo was supported by 2016-T1/SOC-1395 and 2020-5A/SOC-19723 from Comunidad de Madrid, PSI2017-85159-P from AEI and UE/FEDER. M.P.-C. was supported by 2017/01/X/HS6/01332 from the National Science Centre, Poland. P.M. was supported by Aarhus University Research Foundation (AUFF), starting grant: AUFF-E-2019-9-4. B. Bago was supported by ANR grant ANR-17-EURE-0010 (Investissements d’Avenir programme) and ANR Labex IAST. R.M.R. was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP180102384). N.B.D. was supported by CAPES grant no. 88887.364180/2019-00. C.S., K.A.Ś. and I. Zettler were supported by the Carlsberg Foundation (CF16-0444) and the Independent Research Fund Denmark (7024-00057B). J.L. was supported by EXC 2126/1–390838866 under Germany’s Excellence Strategy. K.B. was supported by the following grants from the National Science Centre, Poland: (1) while working on the data collection, no. 2015/19/D/HS6/00641, (2) while working on the final version of the paper, no. 2019/35/B/HS6/00528. A.W. was supported by FONDECYT 11190980, CONICYT. A. Fleischmann was supported by the German Research Foundation (research unit grant FOR-2150, LA 3566/1-2). H.Y. was supported by JSPS grant 18K03010. Y.Y. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (16H03079, 17H00875, 18K12015 and 20H04581). K.Q. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (17H06342, 20K03479 and 20KK0054). A. Ikeda was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (20J21976). K.M.K. was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grant no. 31530032 and Key Technological Projects of Guangdong Province grant no. 2018B030335001. J.B.C. was supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship grant no. DGE-1839285. M. Parzuchowski, K. Rybus and N.M.S. were supported by Polish National Science Center and DFG Beethoven grant 2016/23/G/HS6/01775. A.C.S. was supported by Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology grant no. SFRH/BD/126304/2016. L. Boncinelli was supported by PRIN 2017 grant no. 20178293XT (Italian Ministry of Education and Research). M.F.F.R. was supported by PSA 006 BRA 008 Data Collection in Support of PSADM 001 Measurement Invariance Project. M. Misiak was supported by a scholarship from the Foundation for Polish Science (START) and by a scholarship from the National Science Centre (2020/36/T/HS6/00256). P.B. was supported by Slovak Research and Development Agency project no. APVV-18-0140. M.A. was supported by Slovak Research and Development Agency project no. APVV-17-0418 and project PRIMUS/20/HUM/009. A. Findor and M.H. were supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. APVV-17-0596. T.G. was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (no. 950-224884). P.P. was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2016-06793). Y.L. was supported by The Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (grant no. 2020SJA0017). M. Kowal was supported by a scholarship from the National Science Centre (2019/33/N/HS6/00054). P.A. was supported by UID/PSI/03125/2019 from the Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions