Abstract

Monolithic all-perovskite tandem photovoltaics promise to combine low-cost and high-efficiency solar energy harvesting with the advantages of all-thin-film technologies. To date, laboratory-scale all-perovskite tandem solar cells have only been fabricated using non-scalable fabrication techniques. In response, this work reports on laser-scribed all-perovskite tandem modules processed exclusively with scalable fabrication methods (blade coating and vacuum deposition), demonstrating power conversion efficiencies up to 19.1% (aperture area, 12.25 cm2; geometric fill factor, 94.7%) and stable power output. Compared to the performance of our spin-coated reference tandem solar cells (efficiency, 23.5%; area, 0.1 cm2), our prototypes demonstrate substantial advances in the technological readiness of all-perovskite tandem photovoltaics. By means of electroluminescence imaging and laser-beam-induced current mapping, we demonstrate the homogeneous current collection in both subcells over the entire module area, which explains low losses (<5%rel) in open-circuit voltage and fill factor for our scalable modules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Triggered by the advances of single-junction organic–inorganic metal halide perovskite solar cells (PSC) with a wide range of bandgaps1,2,3, perovskite-based tandem photovoltaics (PVs) have come into research focus in recent years4,5,6,7. The promise of any tandem PV technology lies in high power conversion efficiencies (PCEs), beyond the Shockley–Queisser limit of single-junction solar cells8,9,10,11. Along with perovskite/silicon12,13,14 and perovskite/Cu(In,Ga)Se215,16,17 tandem photovoltaics, two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells (2TPT-SCs) have raised great interest in recent years, combining a wide bandgap (WBG) perovskite top subcell (EG-top ≈ 1.6–1.8 eV) and a narrow-bandgap (NBG) perovskite bottom subcell (EG-bottom < 1.3 eV)4,5,6,7,18,19,20,21,22,23. Several studies reported efficiencies of laboratory-scale 2TPT-SCs exhibiting a PCE of >23% (refs. 7,18,20,21,24,25), with the current certified record being 26.4% (ref. 26). Considering that these values exceed the PCEs of commercial single-junction multicrystalline silicon or copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) cells27,28, it is time to take the next step and develop scalable fabrication processes and interconnection schemes for 2TPT-solar modules (2TPT-SMs).

While laser-scribed interconnection schemes of single-junction perovskite solar modules were successfully implemented in the past at very high geometrical fill factors of >98% (ref. 29), there is yet no report addressing the very specific challenges of the monolithic all-perovskite tandem module. Similar to single-junction perovskite solar modules, scaling 2TPT-SCs will adapt the established thin-film module interconnection concept of elongated PSC stripes that are separated by equidistant interconnections formed by three scribing lines16,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. However, realizing laser-scribed interconnection lines in 2TPT-SMs necessitates processing in an inert atmosphere and a scribing process that is compatible with a tandem solar cell layer stack containing two types of perovskite thin films.

Next to the module interconnection, 2TPT-SM device architectures processed with industrially scalable deposition methods need to be developed. So far, all 2TPT-SCs have required several spin-coating steps, which limited the device area to a laboratory scale of up to around 12 cm2 (ref. 25). For large areas, scalable methods such as thermal evaporation37, blade coating35,38,39, spray coating40 and slot-die coating41,42 have been investigated for perovskite photovoltaics. Among them, blade coating (PCE: 17.8%)39 and slot-die coating (PCE: 20.8%)42 have demonstrated remarkable potential in processing single-junction perovskite solar modules. The key challenge in processing 2TPT-SMs with scalable solution-based methods is the sequential layer deposition considering the similar solubility of the WBG and NBG perovskite layer in the top and bottom cell, respectively. The latter poses a major hurdle to the sequential deposition of the 2TPT device architecture as it induces facile degradation of the underlying layer (for example, the WBG perovskite) when processing the solution of the NBG bottom solar cell.

In response to the above-mentioned challenges in upscaling 2TPT PV, this study reports on laser-scribed 2TPT-SMs processed exclusively with scalable fabrication techniques. The study introduces the scientific and technological advances that led to these prototypes. First, we introduce our reference device architecture, which benefits from reduced optical losses and shows close performance in small-scale 2TPT-SCs (aperture area of 0.1 cm2) compared to the record devices reported in the literature26. Second, we report on a high-throughput laser-scribing process in an inert atmosphere and demonstrate high geometric fill factors (GFF) in small-scale spin-coated 2TPT-SMs (aperture area of 2.25 cm2, referred to as ‘spin-coated 2TPT-SMs’). Using time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), we reveal the highly selective laser patterning of the scribing lines. Finally, we demonstrate 2TPT mini-modules (aperture area of 12.25 cm2, referred to as ‘scalable 2TPT-SMs’) processed exclusively with scalable fabrication methods using a combination of blade-coating and vacuum-based deposition methods. To allow for degradation-free deposition of the NBG bottom cell on top of the WBG top cell with blade coating, we employ vacuum-assisted growth control (VAGC)43, which swiftly extracts all solvents. Through electroluminescence and photoluminescence (PL) imaging, as well as laser-beam-induced current mapping (LBIC), homogeneous current generation and collection over the entire 2TPT-SM area are demonstrated, which is consistent with the low losses in open-circuit voltage (Voc) and fill factor (FF).

Spin-coated all-perovskite tandem solar cells and modules

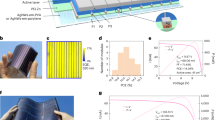

The starting point of this study is a spin-coated 2TPT-SCs in p–i–n architecture that builds on previous reports (Supplementary Notes 1–5, Supplementary Figs. 1–20 and Supplementary Table 1), but exhibits low optical losses and high PCE of up to 23.5% (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Fig. 19). The PCE of our spin-coated 2TPT-SCs is high enough to take a further step for upscaling7,18,25,26 (Fig. 1a,b), using the following layer stack (HTL, hole transport layer; ETL, electron transport layer): front electrode: hydrogenated indium oxide (IO:H)|HTLtop: (2-(9H-carbazol-9-yl)ethyl)phosphonic acid (2PACz)|WBG perovskite absorber (FA0.8Cs0.2(I0.6Br0.4)3, EG ≈ 1.78 eV)|LiF|ETLtop: fullerene (C60)/SnOx|recombination layer: indium tin oxide (ITO, ~15 nm)|HTLbottom: poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS)|NBG perovskite absorber (Csx(FA0.83MA0.17)(1−x)Sn0.5Pb0.5I3, EG ≈ 1.26 eV)|ETLbottom: phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM)/C60|bathocuproine (BCP)|back electrode: Cu (Fig. 1a). The stable power conversion efficiency (SPCE) of these devices is confirmed and a champion SPCE of 23.4% (5 min of maximum power point (MPP) tracking, nitrogen atmosphere and room temperature) is demonstrated (Fig. 1b, inset). This performance is achieved by lowering the parasitic absorption losses in the transparent conducting oxide (TCO) electrode at the front side of the top subcell (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3), the losses in the HTL of the top subcell (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), the losses in the recombination junction (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 6–12), the losses in the HTL in the bottom subcell (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figs. 13–15) and the reflection losses (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Figs. 16–20).

a, Schematic and layer stack of all-perovskite tandem solar cells applied in this work. The champion tandem solar cells and modules employ sputtered indium tin oxide layers (thickness ~15 nm) and percolated Au thin films (nominal thickness ~1–2 nm) as a recombination layer, respectively. NBG and WBG are the abbreviations of the narrow and wide bandgap. b, Current density–voltage (J–V) curve and power conversion efficiency tracked at the maximum power point of the champion tandem devices for 5 min (in the inset). c, EQE of top and bottom subcell as well as the sum of both (grey symbolled line), and total absorbance calculated by 1 − reflectance (black solid line) for monolithic all-perovskite tandem solar cells. The light and dark blue regions denote the parasitic absorption and reflection losses, respectively. The corresponding losses in current density are provided. d, Schematic illustration of the two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar module (not to scale) interconnection denoting the active area and scribing lines (for more details see Supplementary Fig. 21). The colour used for the module layers is the same as for tandem solar cells. e, J–V characteristics of individual tandem cell stripes of the module and the respective fill factors after a stepwise inclusion of cell stripes included in the measurement. f, Power, voltage and current at the maximum power point of the champion tandem solar module under continuous AM 1.5G illumination. g, Normalized power (Norm.), voltage and current at the maximum power point under temperature stress at 85 °C in nitrogen atmosphere. Panels a–c refer to tandem solar cells while panels d–g to tandem modules.

While notable advances have been reported in the performance and short-term stability of spin-coated 2TPT-SCs up to 12 cm2 (ref. 25), these devices were yet limited to laboratory-scale tandem solar cells. Xiao et al. showed that by the use of surface-anchoring zwitterionic molecules in the NBG perovskite, a uniform layer of NBG perovskite can be achieved by spin coating. This enabled them to reach a higher active area of 12 cm2 in the 2TPT-SCs with a notable PCE of 21.4% (ref. 25). Upscaling to larger areas requires the development of thin-film modules with two-terminal interconnected cell stripes, which allows operating the module at high voltages and low currents. The established route to realizing an efficient thin-film module interconnection employs three interconnection lines (called P1, P2 and P3), as shown schematically in Fig. 1d (for more details see Supplementary Fig. 21). The area between P1 and P3 interconnection lines is inactive, which denotes an associated area loss quantified by the GFF (Supplementary Fig. 21). Mitigating the risk for interconnection-induced shunts between the back or front contact and the recombination layer, we note that the percolated Au layers provide a higher yield compared to ITO recombination layers. We attribute this to the low lateral conductivity of our percolated Au layers (in the range of MΩ), which makes this architecture less sensitive to shunts from either electrode to the recombination layer at or near the scribing lines (Supplementary Fig. 11).

The disadvantage of the percolated Au layers is a reduced transmission compared to ITO recombination layers (Supplementary Fig. 10). According to our observations, even the conductivity of thin ITO layers of thickness ~15 nm (~450–500 Ω sq−1 sheet resistance) is sufficient to induce notable shunt resistance losses. For this reason, a percolated Au recombination layer is employed here despite the high parasitic absorption losses. These absorption losses are attributed to plasmonic losses of percolated Au layers in the recombination junction (SnOx/Au/PEDOT:PSS), even at the lower nominal thicknesses of Au down to 0.3 nm (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 6–12). However, neither a percolated Au recombination layer nor a thin ITO recombination layer (~15 nm) are optimal and substantial future improvement potential lies in the development of improved recombination or tunnel junctions for all-perovskite tandem PVs.

Figure 1e shows an all-laser-scribed spin-coated 2TPT-SM comprising four serially interconnected cell stripes with a total aperture area of 2.56 cm2 and a 94.7% GFF (Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Fig. 21a,b). It should be noted that the low stability of mixed Sn/Pb-based perovskite narrow-bandgap bottom solar cells poses a general challenge to the industrial upscaling of all-perovskite-based tandem photovoltaics. Exposure of the devices to the ambient atmosphere needs to be avoided at any stage. For this purpose, a custom-built laser-scribing set-up is employed for the fabrication of the monolithic interconnections of 2TPT-SMs; the set-up allows patterning in an inert atmosphere to prevent O2 exposure and degradation of the NBG bottom subcell during the scribing process.

Compared to other thin-film module technologies (GFF up to 96% (ref. 44)), as well as single-junction perovskite modules (GFF ~95% (refs. 16,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,45)), the achieved GFF of 94.7% is very respectable. For details on the laser-scribing process, we refer to the experimental section and Supplementary Fig. 21. As shown in Fig. 1e, the Voc of each cell stripe of the spin-coated tandem module corresponds to around 2.01 V, while the total Voc of the module equates to the expected 8.0 V (Fig. 1e). This implies a minimal loss in Voc of only 10 mV per cell stripe (0.5% relative). Moreover, our modules retain a high FF of 75%, demonstrating a negligible detrimental effect of introduced module interconnections (compared with single-junction solar cells showing FF of ~75%; Fig. 1b). Our in-house measurement of the champion module (without encapsulation and masking, measured in ambient atmosphere) with an aperture area of 2.56 cm2 (defined by laser scribing) exhibits a high PCE of 22.2% (23.7% active area PCE) with Voc = 8.0 V, short-circuit current Isc = 9.57 mA and FF = 75% (Fig. 1e). The MPP tracking of the modules under continuous illumination (1 Sun) shows a SPCE of 21.4% (and stable power output of 54.7 mW) for 15 hours (Fig. 1f). Moreover, the module shows stable power output at the maximum power point for 3.5 hours and 85°C in an inert atmosphere (Fig. 1g).

The good performance of the spin-coated 2TPT-SM was certified by the accredited CalLab PV Cells of Fraunhofer ISE. Given the sensitivity of the NBG perovskites towards ambient atmosphere and the requirements of the certification standards, the module was encapsulated and covered with an additional external mask. The encapsulated and masked champion module (aperture area of 2.43 cm2) exhibited an in-house PCE of 19.8% (I–V measurement, backward scan) and an externally measured PCE of up to 18.3% (Fraunhofer ISE CalLab PV Cells). The certified PCE determined by steady-state MPP is 17.99% ± 0.63% (Fraunhofer ISE CalLab PV Cells, see Supplementary Fig. 22). The apparent difference between the certified and in-house PCE is attributed to degradation losses that originate from the encapsulation process (which is conducted in ambient atmosphere) and the extended time of transfer (see Supplementary Fig. 22, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Note 6 for a detailed discussion). Therefore, to reach higher stability for the 2TPT-SMs, proper encapsulation under an inert atmosphere is required. Further advances in the stability of all-perovskite tandem photovoltaics will be inspired by the research and development of additives and passivation layers, such as the latest work of Lin et al., which demonstrated high stability by grain-boundary passivation26.

Using ToF-SIMS, we provide a three-dimensional (3D) depth profile of the material composition at the 2TPT-SMs interconnection, highlighting the selective laser-ablated material removal at the P1, P2 and P3 interconnection line (Fig. 2a–c). By overlaying the depth profiles of all materials (Supplementary Fig. 23) and the underlying planar glass layer, the 3D depth profile (Fig. 2c) illustrates the material composition at the interconnection lines and the selective laser-ablated material removal. The dimension of the P1–P3 scribing investigated here by ToF-SIMS exhibits a very similar width (dead area) compared to the previous analysis via scanning electron microscopy (SEM), of 220 µm (Fig. 2b). Considering the dead area width of 210 µm, which can be estimated by ToF-SIMS, we determine a GFF of 94.7% (±0.1%).

a, Photograph of a tandem solar module with four tandem cell stripes and a total aperture area of 2.56 cm2. b, SEM image of scribing lines indicating the P1–P3 interconnections. c, Combined fragments of Au− (yellow), C2− (red), InO− (green) and SiO− (dark violet, please see Supplementary Fig. 23). The combined 3D mapping of Au, perovskite, IO:H and SiOx fragments visualizes the complete tandem architecture and scribing lines. d, Schematic of our laser excitation to measure the LBIC signal of photogenerated currents in top and bottom subcells. e,f, LBIC signal of the top (e) and bottom (f) subcells in the tandem module excited with 530 and 850 nm lasers, respectively. g, Schematic of electroluminescence imaging and the applied optical shortpass (SP, at 775 nm) and longpass (LP, at 760 nm) filters. h,i, Electroluminescence imaging of the top (h) and bottom (i) subcells by use of 775 nm shortpass and 760 nm longpass filters, respectively. The black arrows indicate defects and/or inhomogeneities in the bottom and top subcells.

Having investigated the selective laser-ablated material removal by means of 3D profiles and SEM surface scans, we assess the homogeneity of the tandem module with regard to: (1) photocurrent generation in the subcells over the entire module area using LBIC mapping; and (2) individual defects and shunts in the top and bottom subcells of the module by electroluminescence imaging.

To study the homogeneity of photocurrent generation in each subcell of our tandem module, we employed an adaptable configuration of LBIC mapping (Fig. 2d–f). The layer stack of modules for the LBIC study is identical to the tandem modules as shown in Fig. 1a (employing Au as a recombination layer). Conventional LBIC is an established method to investigate the homogeneity of perovskite layers in single-junction solar cells and modules46,47,48,49,50. To discriminate between the photogenerated current in the top and bottom subcells, the LBIC set-up is expanded by a second excitation laser, and now comprises laser sources of wavelength 530 nm and 850 nm, respectively. First, exciting the module with the 530 nm laser, we track the LBIC signal in the top subcell, as photons of this wavelength are fully absorbed in the WBG perovskite absorber layer (Fig. 2d,e). The corresponding LBIC map shows uniform photocurrent generation in the entire active area of the module. Second, using the 850 nm laser, we selectively excited the bottom subcell, as photons of this energy are not absorbed by the WBG perovskite top subcell, but only by the NBG perovskite bottom subcell (Fig. 2d,f). Similar to the LBIC map of the top subcell, the LBIC signal of the bottom subcell also exhibits a homogeneous signal over the entire module area. Interestingly, some defects are apparent as dark spots in the LBIC signal of the top subcell but appear bright in the LBIC signal of the bottom subcell. These defects are attributed to pinholes in the top subcell and inhomogeneity in the perovskite thin-film thickness. Overall, the LBIC data prove an even photocurrent generation and extraction over the entire active area for both the top and bottom subcells of our module.

To study the distribution of local defects and confined local charge barriers in our tandem modules, we further employ electroluminescence imaging, which exhibits only indirect information on current collection but at much higher resolution (for our set-up a pixel coarsely represents about 13 µm × 13 µm) compared to LBIC (our LBIC resolution is limited by laser spot diameter;51 ~200 µm and 500 µm in our measurements). To distinguish the electroluminescence signal of the two subcells in our tandem module (1.78 eV WBG perovskite top subcell (Supplementary Fig. 24) and 1.26 eV NBG perovskite bottom subcell52), the electroluminescence signal is imaged with: (1) a neutral density filter to track the full electroluminescence signal; (2) a longpass filter (~760 nm) for imaging the bottom subcell; and (3) a shortpass filter (~775 nm) for imaging the top subcell (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Figs. 25–27 and Supplementary Video 1). Given the two-terminal series connection of the top and bottom subcells, the electroluminescence signal rises only for a voltage add-up across each cell stripe close to the sum of the Voc of both subcells (that is, close to 8 V for our module of four cell stripes; see Supplementary Fig. 28). As shown in Fig. 2h,i, the recorded electroluminescence images reveal overall good homogeneity, confirming the LBIC data. However, several local defects are present in the active area (indicated by black arrows for the top and bottom subcells). We attribute these defects to either local variations in charge-carrier injection (due to different series resistance) or local variation in out coupling of luminescence from the device (for example, due to variations in surface roughness and thickness).

At the same time, most features are visible in both electroluminescence images, indicating that the fabrication defects in the top subcell affect the quality of the bottom subcell too. However, some features are only present in images that display the particular defects or inhomogeneity in each subcell (Fig. 2h,i). Although electroluminescence and LBIC analyses agree in terms of homogeneity in the active area as well as laser-scribed interconnection lines, electroluminescence imaging allows us to reveal individual fabrication defects of the modules in both deposition and laser-scribing steps, facilitating process optimization towards high-efficiency 2TPT-SMs (Fig. 2e,f,h,i). Overall, we demonstrate in this section the ability to scale up the spin-coated 2TPT-SCs to modules with only a 6%rel drop in PCE, which is in very good agreement with the GFF loss associated with the module interconnection.

Upscaling all-perovskite tandem solar modules

Having developed an interconnection scheme with high GFF, next we present a scalable 2TPT-SM architecture that enabled a prototype module (aperture area of 12.25 cm2) fabricated with scalable thin-film deposition methods (Fig. 3a,b). The scalable modules employ the same architecture as the spin-coated modules (see also Supplementary Note 7). The fabrication of the modules is conducted with a combination of blade-coating (2PACz, WBG perovskite, PEDOT:PSS, NBG perovskite and PCBM) and vacuum-deposition (LiF, C60, SnOx, Au, BCP and MgF2) methods (Fig. 3a).

a, Schematic of the fabrication sequence for scalable processing of the tandem modules using a combination of blade-coating and vacuum-deposition techniques. b, The front side of the fabricated tandem module with seven cell strips and an aperture area of 12.25 cm2. c, Current density–voltage (J–V) characteristic of stepwise accumulated tandem cell stripes of the module and the respective fill factors. d, Power at the maximum power point of the champion tandem solar mini-module with 12.25 cm2 aperture area under continuous AM 1.5G illumination and nitrogen atmosphere. e, Photoluminescence of the tandem perovskite layers with excitation lasers of 513 nm. The insets are the photoluminescence imaging of the top and bottom subcells by use of 775 nm shortpass and 760 nm longpass filters, respectively. f, Photograph and corresponding J–V characteristics for the electroluminescence image. g, Electroluminescence of the tandem perovskite layers. The insets are the electroluminescence imaging of the top and bottom subcells by use of 775 nm shortpass and 760 nm longpass filters, respectively.

While several of these deposition steps are adapted from the literature (Methods), the processing of the NBG perovskite bottom solar cell required a major innovation to address the challenge of processing the NBG perovskite layer on top of the WBG perovskite top cell without dissolving the underlying layer (see the next section). Prototype modules reached a PCE of 19.1% (aperture area of 12.25 cm2, seven cell strips and 94.7% GFF; Fig. 3c) and 18.3% MPP tracking (corresponds to 224 mW) for 20 hours with less than 7%rel drop (Fig. 3d). As shown in Fig. 3c and Table 1, in the current blade-coated module, the single 2T tandem cell strips with 1.75 cm2 active area on the module show almost the same FF, Voc and Isc (with an average PCE of 19.4%), which results in a 19.1% PCE for modules. Compared to our spin-coated modules with 2.56 cm2 aperture area, the 2TPT modules processed with scalable deposition methods exhibit only a loss of 4% in FF and 100 mV in voltage, which we attribute to inhomogeneity and variations in perovskite thin-film morphology from the blade-coating step (Fig. 3c and Table 1).

To visualize the defects that we associate with the upscaling losses, we conducted photoluminescence imaging as well as electroluminescence imaging, as introduced previously. As shown in Fig. 3e–g, using shortpass (775 nm) and longpass (760 nm) filters, the defects are apparent in the WBG and NBG solar cell and consequently are expected to impact the FF and Voc. As illustrated in the electroluminescence (EL) and photoluminescence imaging, electroluminescence imaging can visualize the defects in more detail compared to photoluminescence imaging due to its high sensitivity to thickness variation, shunts and out coupling (Fig. 3e–g). Position-dependent variations in the thickness of both WBG and NBG perovskites are clearly visualized by EL imaging. Interestingly, the 2T module shows a remarkable electroluminescence signal at a starting voltage of ~12 V (Fig. 3f) with emission from the WBG (688 nm) and NGB (977 nm) perovskite layer, which itself highlights the high quality and homogeneity of our 2TPT modules (Fig. 3g). To investigate the photocurrent generation in the subcells over the entire module, LBIC measurement on a different module is conducted (Supplementary Fig. 29). The black arrows indicate defects and/or inhomogeneities in the bottom and top subcells.

Non-destructive scalable processing of tandem architecture

The key challenge in processing 2TPT modules with scalable solution-based methods is the very similar solubility of the WBG and NBG perovskite layers in the top and bottom cells, respectively6. To prevent degradation of the WBG perovskite top solar cell during the subsequent deposition step of the NBG perovskite layer, in addition to the use of robust interlayers, the resting time of the NBG perovskite solution on the sample needs to be minimized. As we show in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 30, notable corrosion of the WBG subcell, due to penetration of NBG solution through the interlayers, is already apparent after 6 s. For spin-coated devices, the resting time is <5 s (Supplementary Fig. 31), as most of the solution already evaporates during the early phase of the spin rotation, leading to high-performance devices (Fig. 1b). For blade-coated NBG thin films, a simple VAGC step already helps to accelerate the solvent extraction (PV0), but crystallization of the blade-coated NBG perovskite still takes longer (~18 s) than small-size spin-coated samples due to the high amount of DMF:DMSO vapour and thicker perovskite solution (Fig. 4a,c and Supplementary Fig. 31). This slightly longer resting time of the NBG solution causes penetration of solvents through the SnOx barrier layer and consequently degradation of the WBG perovskite in the top subcell (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 30).

a, Degradation rate over time as the ratio of red dots (that is, photoluminescence signal emitted from the degraded regions) to the image area in the photoluminescence images overlaid on the plot. Black indicates no degradation. The photoluminescence images are taken from the WBG/LiF/C60/SnOx/Au/PEDOT:PSS stack after blade coating of the DMF:DMSO mixture after a resting time of 0–20 s. The grey vertical lines indicate the time of formation of the NBG perovskite at different growth conditions of PV0-PV2. b, Schematic of the designed vacuum plus nitrogen flowing chamber for growth of the NBG perovskite. The bottom scheme shows the swapping of the evaporated DMF and DMSO from the surface of the blade-coated perovskite in combination with the simultaneous evacuation and venting of the chamber. The light blue and dark blue layers represent the interlayers and glass/IO:H/2PACz substrate, respectively. c, Pressure versus time characteristic for different growth conditions of NBG in the chamber (PV0-PV2) with defined perovskite formation time (grey vertical lines). d–f, SEM images of the NBG perovskite produced at different growth conditions of PV0 (d), PV1 (e) and PV2 (f).

To further accelerate the extraction of solvents, a moderate nitrogen flow (260 cm3 min−1, PV2) is applied in addition to the vacuum extraction step (Fig. 4b,c), leading to overall faster mass transport of solvents away from the sample surface53. As a result, the resting time of the NBG drops to <5 s, which prevents degradation of the underlying WBG top solar cell (Fig. 4a). Importantly, this nitrogen gas flow-assisted crystallization of the NBG perovskite on the top subcell produces a microscopic, defect-free morphology (PV2; Fig. 4c,f), while in the absence of nitrogen gas flow (PV0; Fig. 4c,d) or insufficient nitrogen gas flow (PV1; Fig. 4c,e) a large number of defects appear that lead to degradation of the WBG perovskite top solar cell by the solvents of the NBG perovskite solution.

The importance of nitrogen gas flow in the VAGC of NBG perovskite thin films is further highlighted by comparing the performance of isolated small-area 2TPT-SCs (aperture area: 0.1 cm2) processed from a large-area substrate (>30 cm2) in the same architecture as the scalable 2TPT-SMs (Supplementary Fig. 32). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 32, 2TPT-SC with NBG perovskite thin films processed only by VAGC show considerably lower overall performance compared to VAGC with gas flow. Furthermore, the different PCE of the devices at different locations on the large-area substrate is attributed to the defects and variation in the thickness of the blade-coated layers at different locations. Therefore, we show that scaling up the 2TPT-SM architecture by scalable deposition methods is feasible as long as very fast extraction of solvents of the bottom subcell is guaranteed. In this work, we employ a combination of VAGC with nitrogen gas flow to realize fast drying of the solution-processed NBG perovskite thin film in a mild vacuum range of 104–105 Pa. Similar to gas quenching, the technique realizes a fast mass transport of evaporated solvents away from the surface of the wet film54. In view of future in-line large-area production, gas quenching, as well as combinations of vacuum quenching with gas flow, would need to be realized shortly after the slot- or blade-coating step to ensure sufficiently fast drying.

Overall, this work highlights the facile upscaling route of the 2TPT-SCs from 0.1 cm2 up to 12.25 cm2 in 2TPT-SMs. Having employed only scalable deposition techniques (blade coating and vacuum deposition) for all 12 layers of the fabricated 2TPT-SMs, the feasibility of upscaling this technology is proven. The demonstrated GFF of our tandem module is comparable to other thin-film PV technologies, such as tandem thin-film silicon photovoltaics (~98% GFF)29 and CIGS photovoltaics (~93% GFF)55. It is noteworthy that the laser set-up applied in this work uses a rather conventional and inexpensive nanosecond laser that is less complex than the widely used picosecond or femtosecond lasers for thin-film solar module patterning in laboratory-scale modules. The technological bottleneck of the current development remains the limited stability of the 2TPT-SMs18,24. Fortunately, given recent advances in engineering the composition7,20,24 as well as defect passivation of NBG solar cells21,26, there is encouraging progress in improvement in the stability of the NBG bottom subcell.

Conclusions

This work advances two-terminal all-perovskite tandem photovoltaics by introducing a scalable high-efficiency, two-terminal, all-perovskite tandem module. The upscaling of laboratory-scale, spin-coated, two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells (0.1 cm2, PCE of 23.5%) to laboratory-scale modules (12.25 cm2 aperture area) is realized by a combination of vacuum-based deposition processes and blade coating, as well as a scalable interconnection scheme. For successful upscaling and degradation-free growth of NBG on the WBG at the top subcell, a vacuum-assisted growth control is employed. The module interconnection is realized with an all-laser-scribed patterning process in an inert atmosphere, enabling a GFF of up to 94.7%. The best spin-coated and scalable modules presented here demonstrates a PCE of 22.2% (aperture area of 2.56 cm2) and 19.1% (aperture area of 12.25 cm2), respectively. The prototype module presents 95% of initial SPCE for 15 h MPP tracking under continuous AM 1.5G illumination. ToF-SIMS measurements reveal selective and uniform scribing, as well as a well-defined GFF (~94.7% ± 0.1%). By means of electroluminescence and photoluminescence imaging, as well as LBIC mapping, we demonstrate homogeneous current collection and a low defect density over the entire module area, which explains the low losses in Voc and FF for our spin-coated tandem modules (<2%rel) and reasonable loss in upscaling the modules by use of blade coating and vacuum deposition (<5%rel).

Methods

Preparation of the precursor solution for the NBG Csx(FA0.83MA0.17)(1−x)Sn0.5Pb0.5I3 absorber

The NBG perovskite solution was prepared following the recipe described in our previous work52. A 2 M concentration NBG solution was used. In brief, to prepare 1 ml NBG perovskite solution, we dissolved 275 mg formamidinium iodide (FAI, GreatCell), 63.6 mg methylammonium iodide (MAI, GreatCell), 372 mg tin iodide (SnI2, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.999%), 469 mg lead iodide (PbI2, Alfa Aesar, 99.999%), 10.43 mg lead thiocyanate (Pb(SCN)2, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.5%) and 3.73 mg tin fluoride (SnF2, Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) in a 9:1 (v:v) mixture of dimethylformamide (DMF, Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, 99.8%) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, ≥99.9%). We added 32 µl of a previously prepared cesium iodide (CsI, Alfa Aesar) stock solution (1.5 M CsI in DMSO) into 1 ml of the NBG perovskite solution. The solution was kept overnight in a nitrogen glovebox (O2 < 0.2 ppm and H2O < 0.4 ppm) and, just before deposition, it was filtered using a 0.2 µm PTFE filter.

Preparation of the precursor solution for the WBG FA0.8Cs0.2(I0.6Br0.4)3 absorber

The 1 M precursor solution for the WBG perovskite processing was prepared by mixing 82.5 mg FAI, 40 mg FABr, 31.1 mg CsI (Alfa Aesar), 17 mg CsBr (Alfa Aesar), 276.6 mg PbI2 and 146.8 mg PbBr2 in 4:1 DMF:DMSO.

Deposition of the NBG Csx(FA0.83MA0.17)(1−x)Sn0.5Pb0.5I3 thin film

To deposit the NBG perovskite, we used our previously reported VAGC method43. In brief, the NBG perovskite thin film was deposited by spin coating the NBG perovskite solution on the PEDOT:PSS substrate at 6,000 r.p.m. for 12 s dynamically to avoid degradation of the top subcell. The wet film was directly transferred into a vacuum chamber (~10 Pa) with a 150 ml volume. After exposing the wet film to vacuum for 10 s, the perovskite thin film was annealed at 100 °C for 7 minutes. The final perovskite thin film exhibits a thickness of about 800 nm. The whole process of deposition, vacuum treatment and annealing of the perovskite thin film was conducted in a nitrogen-filled glovebox (O2 < 0.2 ppm and H2O < 0.4 ppm).

Deposition of the WBG FA0.8Cs0.2(I0.6Br0.4)3 thin film

The WBG perovskite thin films were deposited by a two-step spin-coating process: (1) 1,000 r.p.m. for 10 s with a ramp of 2,000 r.p.m. s−1 and (2) 6,000 r.p.m. for 30 s with a ramp of 2,000 r.p.m. s−1. At 19 s before the end of the spin-coating process, 150 µl ethyl acetate was manually applied as an antisolvent onto the wet film. The samples were annealed on a hotplate at 150 °C for 20 minutes. Deposition and annealing of the perovskite absorber were conducted in a nitrogen-filled glovebox (O2 < 0.2 ppm and H2O < 0.4 ppm).

Atomic layer deposition of the SnOx

SnO2 layers were fabricated by atomic layer deposition (ALD) in a Picosun ALD system (Picosun R200) at 90 °C using the precursors tetrakis(dimethylamino)tin(IV) (TDMASn) (99.99%-Sn, Strem Chemicals) and water. High-purity argon (Ar, 99.999%) was used as carrier gas and purge gas. The line flows of TDMASn and water were set to 120 and 150 standard cubic centimetres per minute (sccm), respectively. The TDMASn source container was preheated for 1 hour at 70 °C, to ensure thermal equilibrium, before the deposition and the water precursor was unheated and pulsed at room temperature. A 35 nm thick SnOx film was deposited by 300 cycles using these settings: TDMASn (pulse time 1.6 s, purge time 12 s) and water (pulse time 0.1 s, purge time 16 s). Due to the machine layout, a boosting system was utilized instead of the conventional bubbler. In this system, the line flow was increased to 500 sccm immediately before pulsing, to facilitate an increased precursor concentration. The increased time of this process is the cause of the abnormally high TDMASn pulse time (normal pulse times are <0.5 s).

Fabrication of the control two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cell with Arch. 2

Two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells with Arch. 2 architecture were fabricated in the p–i–n architecture. Glass substrates coated with a 140 nm thick ITO front electrode (sheet resistance 15 Ω sq−1, Luminescence Technology) were used. The substrates were cleaned consecutively in deionized water, acetone and isopropanol for 10 min each in an ultrasonic bath. Immediately before deposition of the HTL, substrates were treated using oxygen plasma for 3 min. As HTL, poly(bis(4-phenyl)(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)amine (PTAA, 2 mg ml−1 in toluene) was used. For deposition of the PTAA, 60 µl of the PTAA solution in toluene was deposited onto the substrate (16 mm by 16 mm) by spin coating at 6,000 r.p.m. for 30 s, followed by annealing at 100 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were transferred to a glovebox for deposition of the perovskite thin film. A 15 nm thick C60 thin film was deposited by thermal evaporation (OPTIvap, CreaPhys) as an ETL. Subsequently, a 35 nm thick SnOx thin film was deposited by ALD. As a recombination layer, different thicknesses of Au, of 0.3, 0.6, 1.2 and 1.8 nm, were deposited on the SnOx layer by thermal evaporation with a low rate of 0.1 Å s−1 to reach the maximum possible uniformity of Au on the substrates. After filtering the aqueous PEDOT:PSS dispersion (Ossila, AI 4083) with a 0.45 µm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) filter, the solution was deposited on the substrates directly by spin coating at 6,000 r.p.m. for 30 s dynamically to avoid degradation of the sublayers. Next, the substrates were annealed on a hotplate at 120°C for 20 min. Afterward, fullerene (C60, ~25 nm) and BCP (~7 nm) were thermally evaporated as the electron transport material, followed by the deposition of a Cu (~150 nm) or Au (~60 nm) thin film as the rear electrode. The active area of the two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells was 0.1 cm2.

Fabrication of the two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cell with modified architecture (Arch. 1)

Similarly to the control sample with Arch. 2, the samples with modified architectures of two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells (Arch. 1) were fabricated in the p–i–n architecture. Glass substrates coated with a 230 nm thick IO:H front electrode were used56. Cleaning the substrates was conducted in the same way as for the control samples. For HTL, 2PACz (0.375 mg ml−1 in ethanol) was used. For deposition of the 2PACz thin film, 70 µl of the 2PACz solution in ethanol was deposited on the substrate by spin coating at 3,000 r.p.m. for 30 s followed by annealing at 100 °C for 10 min. After deposition of the WBG perovskite, a 1 nm thick LiF thin film was deposited on the WBG perovskite. As for the control samples, a 15 nm thick C60 thin film was deposited by thermal evaporation as an ETL and, subsequently, a 35 nm thick SnOx thin film was deposited by ALD. As a recombination layer, a 15 nm thick ITO thin film was deposited on SnOx via d.c. sputtering. In the modified architecture, after filtering the aqueous PEDOT:PSS with 0.45 µm PVDF filter, the PEDOT:PSS was diluted with ethanol or isopropanol with a 3:1 ratio. The diluted solution was deposited on the substrates with the same spin-coating and annealing parameters as the control samples. After deposition of the NBG perovskite thin film using the VAGC method, a thin film (~5 nm) of PCBM (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.5%) was deposited onto the perovskite thin film using a 5 mg ml−1 solution in 1,2-dichlorobenzene (Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, 99%) in the modified architecture. After deposition of the C60, BCP and rear contact layers, as done for the control samples, finally, a 125 nm thick MgF2 thin film was thermally evaporated on the front side of the glass. The active area of the tandem solar cells was the same as for the control samples.

Fabrication of the spin-coated two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar modules with 2.56 cm2 aperture area

For fabrication of the primitive modules with the spin-coating method and an aperture area of 2.56 cm2, 30 mm by 30 mm IO:H substrates were used (to have extra space for glass–glass encapsulation). We followed all procedures described for the fabrication of small-area (0.105 cm2) 2T tandems with our modified architecture, except for using a higher amount of solution to reach uniform coverage. Furthermore, the modules use a percolated Au as a recombination junction (nominal thickness 1.2 nm). While such percolated Au layers introduce some optical losses, they exhibit a very low lateral conductivity. The architecture of the spin-coated 2TPT-SMs was the same as shown in Fig. 1a, but with a SnOx/percolated Au recombination junction (see also Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Note 7). The laser-scribing procedure described in the next section was used in the fabrication of our modules. The final modules were encapsulated with butyl rubber at ambient atmosphere for further LBIC and electroluminescence characterizations in the atmosphere.

Laser scribing of module interconnection lines

Fabrication of monolithically interconnected two-terminal modules on substrates of 30 mm by 30 mm was facilitated by integrating three scribing lines (P1, P2, P3) in our device stack. On the basis of the modified architecture, P1 was employed to ablate the IO:H, P2 for ablating the multilayers of 2PACz/WBG perovskite/LiF/C60/SnOx/Au/PEDOT:PSS/NBG perovskite/PCBM/C60/BCP and P3 to ablate the rear metal contact. The widths of P1, P2 and P3 were 60, 60 and 40 µm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 21). The entire scribing width encompassing buffer regions was 240 µm. A module layout with a 2.56 cm2 aperture area was used. A custom-built laser-scribing set-up developed in conjunction with Bergfeld Lasertech was employed, integrating a 1 ns Nd:YVO4 laser (Picolo AOT 10-MOPA, InnoLas Laser) with available 1,064 nm and frequency-doubled 532 nm wavelengths, variable pulse repetition rates and power output. All three interconnection lines (P1, P2 and P3) were laser scribed using the same ns laser (wavelength of 532 nm). For alignment and laser spot motion, an X–Y directional scanner system combined with a camera was utilized. All scribing processes were performed from the film side and followed a predefined scribing layout. The scribing part of the system was incorporated in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. P1 laser scribing was performed at a pulse repetition rate of 10 kHz, 50 mm s−1 scribing speed and 2.00 J cm−2 fluence. P2 laser scribing was performed at a pulse repetition rate of 10 kHz, 33 mm s−1 scribing speed and 0.45 J cm−2 fluence. P3 laser scribing was performed at a pulse repetition rate of 10 kHz, 100 mm s−1 scribing speed and 0.40 J cm−2 fluence.

Upscaling the two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar modules with a 12.25 cm2 aperture area

For the fabrication of two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar modules with 12.25 cm2 aperture area, only fully scalable methods were used in the deposition of the entire layer. For this purpose, a combination of vacuum deposition and blade coating (blade gap of 100 μm) was employed. Substrates of 6.4 × 5 cm2 IO:H were used such that the inhomogeneous region in the blade-coating procedure (7 mm from the beginning and 7 mm from the end of the blade-coated substrates) can be cut away. The final substrate size for our modules was 5 × 5 cm2, in which a 0.5 mm distance from each edge was reserved for the glass–glass encapsulation. As shown in Fig. 3b, the modules have an aperture area of 12.25 cm2 (3.5 cm × 3.5 cm), which contains seven cell strips (with an active area of 1.75 cm2 on each). The fabrication of two-terminal tandems was conducted as follows. (1) After P1, deposition of the 2PACz was conducted by blade coating with a rate of 15 mm s−1 followed by drying in a nitrogen atmosphere and annealing at 100 °C for 10 minutes. (2) The WBG perovskite layer was blade coated from a diluted WBG solution (40 vol%) with a solvent mixt (4:1) of DMF:DMSO. Optimal device performance and perovskite thin-film quality (thickness: 400–430 nm, root mean square (r.m.s. roughness: ~20 nm) were obtained for a blade speed of 15 mm s−1. To realize this rather low roughness, a short vacuum quenching step (30 s, 200 cm3 min−1 nitrogen flow) was implemented. The vacuum quenching enables homogeneous crystallization of WBG perovskite thin film. The dry perovskite thin films were annealed at 150 °C for 20 min. It should be noted that the roughness of the WBG perovskite thin film is key to the fabrication yield of the tandem device. While the spin-coated WBG perovskite thin films exhibit an r.m.s. roughness of <10 nm, the blade-coated perovskite thin films exhibit an r.m.s. roughness of ~20 nm. The r.m.s. roughness was assessed by atomic force microscopy measurements. In our optimization procedure, we realized a rougher surface of the WBG causes a low yield of tandem devices due to the degradation of the WBG perovskite by the solvent of the NBG perovskite during deposition. (3) After deposition of the WBG perovskite layer, 1 nm LiF and subsequently 15 nm C60 were deposited by thermal evaporation. (4) Later, a 35 nm thin layer of ALD-deposited SnOx was employed for the protection of WBG perovskite while deposition of PEDOT:PSS and NBG perovskite solution occurred. (5) After deposition of the recombination layer (here 1.2 nm Au to avoid shunting between metal rear contact and recombination layer through P2 scribing line), a 10× diluted PEDOT:PSS (aqueous dispersion) with IPA was blade coated on the substrates. Note that to avoid degradation of WBG perovskite by a small trace of water in PEDOT:PSS and to produce a uniform layer of PEDOT:PSS, a 25 mm s−1 blading speed and 80 °C blade-coating plate temperature is required. (6) Deposition of NBG perovskite layer was conducted by blade coating the diluted solution of NBG (50 vol%) with DMF to reach the same thickness as we could reach by spin coating (~800 nm). After blade coating of the NBG solution, the layers were immediately transferred into the vacuum chamber to extract the solvents and produce the NBG perovskite layer. During this procedure, we realized there was an intensive degradation of the WBG top subcell by solvents of the NBG solution, which deteriorates the entire performance of the modules. Therefore we designed an alternative drying procedure to accelerate the solvent extraction and crystallization of the NBG perovskite. In this regard, the growth of the NBG perovskite was conducted in the vacuum chamber with the assistance of controlled and optimized nitrogen flow to swap the evaporated solvents from the surface of the modules during the crystallization. For this purpose, different nitrogen flows of 0, 180, 260 and 285 cm3 min−1 were investigated. After drying the NBG perovskite layers, they were annealed at 100 °C for 7 minutes. (7) Next, a 10× diluted PCBM solution was blade coated on the NBG layer and dried in the vacuum chamber without any annealing procedure. (8) After deposition of PCBM, 30 nm C60 and 5 nm BCP were deposited on the substrate by thermal evaporation. (9) After the P2 scribing line, a 100 nm thin Au layer was deposited by thermal evaporation, and, finally, P3 scribing lines were used to define the cell strips and final aperture area. (10) Later, a 125 nm MgF2 layer was used as an antireflection coating layer on the glass side of the modules. Finally, (11) the modules were encapsulated with butyl rubber in the glass–glass encapsulation. To define the accurate aperture area, an additional black-painted metal mask was used to define the 12.25 cm2 aperture area for J–V and MPP characterizations.

Current density–voltage measurements

The J–V characteristics of the single-junction solar cells, tandem solar cells and tandem modules were measured with a class AAA solar simulator (Newport Oriel Sol3A) at a power density of 100 mW cm−2, simulating AM 1.5G solar irradiation. The scan rate during measurement was set to 0.6 V s−1 using a source meter (Keithley 2400 A). For NBG single-junction and all tandem solar cells and modules, the solar simulator was calibrated with a certified silicon solar cell (Newport, #2446 and #1758). For J–V measurements of the WBG single-junction perovskite solar cells, a silicon solar cell (Newport) equipped with a KG5 bandpass filter was used for calibration. The stable power output efficiency of the PSCs was determined by tracking the MPP under continuous AM 1.5G illumination. The temperature of the solar cells was actively controlled by a Peltier element connected to a microcontroller and set to 25 °C (85 °C for MPP tracking at thermal stress) while conducting the J–V analyses and MPP tracking. As the J–V characteristics are measured with a single lamp solar simulator, the Jsc reported is adapted to the external quantum efficiency (EQE) measurements. The J–V measurement of the modules was conducted without controlling the temperature, which caused an increase in temperature up to 60 °C in the long-term measurement. The active area of the WBG and NBG single-junction perovskite solar cells was defined by a mask of 0.1 cm2. The aperture area of the laser-scribed modules was defined by laser scribing (2.56 cm2). For the certification, additional external manual masking of the module was required, which decreased the aperture area to 2.43 cm2. For the measurements of the 12.25 cm2 modules, a metal mask with a 12.25 cm2 aperture area was used. For the latter device, no difference with and without a mask was apparent, highlighting the accuracy of the laser scribing.

SEM

Field emission cross-sectional and top-view SEM images of two-terminal all-perovskite tandems solar cell, interconnection of the module, thermal-evaporated Au layer and sputtered ITO thin film were taken with a ZEISS Supra60 VP scanning electron microscope.

Optical characterization and EQE measurements

The absorption spectra of the perovskite thin films and devices were measured with a Bentham PVE300 photovoltaic service characterization system by illuminating the solar cell with modulated monochromatic light. For the EQE measurements of the tandem solar cells, we followed the steps recommended in the literature57. A filtered bias light with a bandpass region 335–610 nm (FGB37M) was used to measure the bottom subcell, and a longpass filter with cut-on wavelength at 850 nm (FGL850M) was used for measuring the EQE of the top subcell. The bias voltage was varied as recommended. The EQE measurements of the subcells were used for correcting the Jsc obtained from J–V measurements.

LBIC

LBIC mapping was performed with a custom-built set-up employing two continuous-wave laser sources of 530 nm and 850 nm for illumination, a lock-in amplifier (SR830, Stanford Research Systems) and a chopper operating at 470 Hz for signal enhancement, and a motorized sample stage for scanning. During measurements, the devices were flushed with nitrogen to hamper degradation in ambient air. X and Y resolution corresponded to 0.2 and 0.5 mm, respectively.

Electroluminescence imaging

The electroluminescence images were acquired with a 2.1 megapixel scientific CMOS camera (Quantalux sCMOS camera, Thorlabs). The electroluminescence was filtered with four different optical filters mounted on a rotating wheel: a 775 nm shortpass (Edmund Optics), a 760 nm longpass (Edmund Optics), 780 nm longpass (Thorlabs) and a neutral density filter (realized by using two stacked linear polarizer LPVISE200, Thorlabs). The modules were biased using a Keithley 2450 SMU. The set-up is shown in Supplementary Fig. 25. The electroluminescence spectra of the cells were acquired using an Ocean Optics HDX spectrometer. All measurements were performed in ambient air on encapsulated samples.

Photoluminescence measurement and imaging

The photoluminescence images were acquired with a 2.1 megapixel scientific CMOS camera (Quantalux sCMOS camera, Thorlabs). The photoluminescence was filtered with two different optical filters mounted on a stationary wheel: a 775 nm shortpass (Edmund Optics) and a 760 nm longpass (Edmund Optics). The modules were excited using a bright blue LED with a 470 nm emission peak wavelength. A 665 nm longpass filter was used to cut out the blue LED interference. The set-up is shown in Supplementary Fig. 25. The photoluminescence signal was collected with a f = 5 cm lens and filtered with a 600 nm longpass. The excitation wavelength was 513 nm at a repetition rate of 20 kHz with a pulse width of approximately 260 fs. The beam area was 0.787 mm2 and the power was 7.9 mW, leading to a fluence of roughly 50 μJ cm−2. The sample (without contact layer and coated with ethyl vinyl acetate) was excited from both sides to obtain the final accumulative photoluminescence spectrum from WBG and NBG perovskites.

ToF-SIMS

Time‐of‐flight secondary ion mass spectrometry was performed on a TOF.SIMS5 instrument (ION‐TOF) equipped with a Bi cluster primary ion source and a reflectron-type time‐of‐flight analyser. For depth profiling, dual-beam analysis was performed in an interlaced mode. The sputter gun operated with cesium ions at 2 keV, scanned over a field of 500 × 500 µm2 (target current 120 nA) and was applied to erode the sample, whereas the primary ion source was scanned over a concentric field of 350 × 350 µm2 (256 × 256 data points). Spectra were calibrated on the omnipresent C−, C2−, C4−, O− and Br− peaks. On the basis of these datasets the chemical assignments for characteristic fragments were determined. For data visualization, secondary ion intensities were rendered to 3D depth profile images.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article and/or its Supplementary Information. Additional original and unprocessed data used in the article, as well as in the Supplementary Information, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, along with reference/calibration measurements and background information.

References

Best Research-Cell Efficiencies (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, accessed 10 May 2022); https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html

Cao, J. & Yan, F. Recent progress in tin-based perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 1286–1325 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Technical challenges and perspectives for the commercialization of solution-processable solar cells. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2000960 (2021).

Eperon, G. E. et al. Perovskite-perovskite tandem photovoltaics with optimized band gaps. Science 354, 861–865 (2016).

Zhao, D. et al. Efficient two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells enabled by high-quality low-bandgap absorber layers. Nat. Energy 3, 1093–1100 (2018).

Palmstrom, A. F. et al. Enabling flexible all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Joule 3, 2193–2204 (2019).

Lin, R. et al. Monolithic all-perovskite tandem solar cells with 24.8% efficiency exploiting comproportionation to suppress Sn(II) oxidation in precursor ink. Nat. Energy 4, 864–873 (2019).

Futscher, M. H. & Ehrler, B. Efficiency limit of perovskite/Si tandem solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 863–868 (2016).

Futscher, M. H. & Ehrler, B. Modeling the performance limitations and prospects of perovskite/Si tandem solar cells under realistic operating conditions. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2089–2095 (2017).

Moghadamzadeh, S. et al. In2O3:H-based hole-transport-layer-free tin/lead perovskite solar cells for efficient four-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 46488–46498 (2021).

Hu, H. et al. Sn-Pb mixed perovskites with fullerene-derivative interlayers for efficient four-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107650 (2022).

Al-Ashouri, A. et al. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell with >29% efficiency by enhanced hole extraction. Science 370, 1300–1309 (2020).

Hou, Y. et al. Efficient tandem solar cells with solution-processed perovskite on textured crystalline silicon. Science 367, 1135–1140 (2020).

Nogay, G. et al. 25.1%-Efficient monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell based on a p-type monocrystalline textured silicon wafer and high-temperature passivating contacts. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 844–845 (2019).

Al-Ashouri, A. et al. Conformal monolayer contacts with lossless interfaces for perovskite single junction and monolithic tandem solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 3356–3369 (2019).

Paetzold, U. W. et al. Scalable perovskite/CIGS thin-film solar module with power conversion efficiency of 17.8%. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 9897–9906 (2017).

Gharibzadeh, S. et al. Heterostructure for semitransparent perovskite solar cells with engineered bandgap enables efficiencies exceeding 25% in four-terminal tandems with silicon and CIGS. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909919 (2020).

Yu, Z. et al. Simplified interconnection structure based on C60/SnO2−x for all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Nat. Energy 5, 657–665 (2020).

Prasanna, R. et al. Design of low bandgap tin–lead halide perovskite solar cells to achieve thermal, atmospheric and operational stability. Nat. Energy 4, 939–947 (2019).

Tong, J. et al. Carrier lifetimes of >1 μs in Sn-Pb perovskites enable efficient all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Science 7911, eaav7911 (2019).

Wei, M. et al. Combining efficiency and stability in mixed tin–lead perovskite solar cells by capping grains with an ultrathin 2D layer. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907058 (2020).

Igual-Muñoz, A. M., Castillo, A., Dreessen, C., Boix, P. P. & Bolink, H. J. Vacuum-deposited multication tin–lead perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2755–2761 (2020).

Zhao, B. et al. High open-circuit voltages in tin-rich low-bandgap perovskite-based planar heterojunction photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604744 (2017).

Li, C. et al. Low-bandgap mixed tin–lead iodide perovskites with reduced methylammonium for simultaneous enhancement of solar cell efficiency and stability. Nat. Energy 5, 768–776 (2020).

Xiao, K. et al. All-perovskite tandem solar cells with 24.2% certified efficiency and area over 1 cm2 using surface-anchoring zwitterionic antioxidant. Nat. Energy 5, 870–880 (2020).

Lin, R. et al. All-perovskite tandem solar cells with improved grain surface passivation. Nature 603, 73–78 (2022).

Wilson, G. M. et al. The 2020 photovoltaic technologies roadmap. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 53, 493001 (2020).

Philipps, S. & Warmuth, W. Photovoltaics Report (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020); https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/de/veroeffentlichungen/studien/photovoltaics-report.html

Booth, H. Laser processing in industrial solar module manufacturing. J. Laser Micro Nanoeng. 5, 183–191 (2010).

Jaysankar, M. et al. Perovskite-silicon tandem solar modules with optimised light harvesting. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1489–1498 (2018).

Jaysankar, M. et al. Four-terminal perovskite/silicon multijunction solar modules. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602807 (2017).

Jaysankar, M. et al. Toward scalable perovskite-based multijunction solar modules. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 27, 733–738 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. A holistic approach to interface stabilization for efficient perovskite solar modules with over 2,000-hour operational stability. Nat. Energy 5, 596–604 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. Trapping lead in perovskite solar modules with abundant and low-cost cation-exchange resins. Nat. Energy 5, 1003–1011 (2020).

Deng, Y. et al. Surfactant-controlled ink drying enables high-speed deposition of perovskite films for efficient photovoltaic modules. Nat. Energy 3, 560–566 (2018).

Jiang, Y. et al. Reduction of lead leakage from damaged lead halide perovskite solar modules using self-healing polymer-based encapsulation. Nat. Energy 4, 585–593 (2019).

Abzieher, T. et al. From groundwork to efficient solar cells: on the importance of the substrate material in co-evaporated perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2104482 (2021).

Yang, M. et al. Perovskite ink with wide processing window for scalable high-efficiency solar cells. Nat. Energy 2, 17038 (2017).

Chen, S., Xiao, X., Gu, H. & Huang, J. Iodine reduction for reproducible and high-performance perovskite solar cells and modules. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8130 (2021).

Kim, J. et al. Overcoming the challenges of large-area high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1978–1984 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Slot-die coating large-area formamidinium-cesium perovskite film for efficient and stable parallel solar module. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg3749 (2021).

Li, J. et al. 20.8% Slot-die coated MAPbI3 perovskite solar cells by optimal DMSO-content and age of 2-ME based precursor inks. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003460 (2021).

Abdollahi Nejand, B. et al. Vacuum-assisted growth of low-bandgap thin films (FA0.8MA0.2Sn0.5Pb0.5I3) for all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902583 (2020).

Jia, Z. et al. 19.34 cm2 large-area quaternary organic photovoltaic module with 12.36% certified efficiency. Photonics Res. 9, 324–330 (2021).

Ritzer, D. B. et al. Upscaling of perovskite solar modules: the synergy of fully evaporated layer fabrication and all-laser-scribed interconnections. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 30, 360–373 (2022).

Aydin, E. et al. Interplay between temperature and bandgap energies on the outdoor performance of perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells. Nat. Energy 5, 851–859 (2020).

Ren, A. et al. Efficient perovskite solar modules with minimized nonradiative recombination and local carrier transport losses. Joule 4, 1263–1277 (2020).

Wong-Stringer, M. et al. A flexible back-contact perovskite solar micro-module. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1928–1937 (2019).

Lee, S. W. et al. Perovskites fabricated on textured silicon surfaces for tandem solar cells. Commun. Chem. 3, 37 (2020).

Phillips, A. B. et al. High speed, intermediate resolution, large area laser beam induced current imaging and laser scribing system for photovoltaic devices and modules. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 93708 (2016).

Lim, J. C., Lorenzo, P. A. C. & MacAbebe, E. Q. B. Cost-effective LBIC system for solar cell characterization. In IEEE Reg. 10 Annu. Int. Conf. Proc./TENCON 2015 1–4 (IEEE, 2016).

Moghadamzadeh, S. et al. Triple-cation low-bandgap perovskite thin-films for high-efficiency four-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 24608–24619 (2020).

Mathies, F. et al. Gas flow-assisted vacuum drying: identification of a novel process for attaining high-quality perovskite films. Mater. Adv. 2, 5365–5370 (2021).

Ternes, S. et al. Drying and coating of perovskite thin films: how to control the thin film morphology in scalable dynamic coating systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 11300–11312 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Effects of laser-scribed Mo groove shape on highly efficient Zn(O,S)-based Cu(In,Ga)Se2 solar modules. Sol. RRL 4, 1900510 (2020).

Schultes, M. et al. Sputtered transparent electrodes (IO:H and IZO) with low parasitic near-infrared absorption for perovskite-Cu(In,Ga)Se2 tandem solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 7823–7831 (2019).

Timmreck, R. et al. Characterization of tandem organic solar cells. Nat. Photon. 9, 478–479 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the great spirit of the perovskite photovoltaics taskforce at KIT. B.A.N. acknowledges financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 840937, as well as Alexander von Humboldt (Georg Forster Research Fellowship). S.M. acknowledges the DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch-dienst/German academic exchange service) for funding her doctoral research work (reference number 91621525). H.H. was financially supported by China Scholarship Council (CSC). Financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (CAPITANO, funding code: 03EE1038B) and the Helmholtz Association—specifically the HYIG of U.W.P. (VH-NG-1148), the Professorial Recruitment Initiative of B.S.R., the Helmholtz Energy Materials Foundry (HEMF), PEROSEED project (ZT-0024), and Research Field Energy: Program Materials and Technologies for the Energy Transition (Topic 1 Photovoltaics and Wind Energy, ref. 38.01.03 and 38.01.04)—as well as the Karlsruhe School of Optics and Photonics (KSOP) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A.N. and U.W.P. developed the idea and designed the experiments of this study. D.B.R. conducted the scribing for modules using pulsed laser ablation for the cell area definition and two-terminal serial interconnection. B.A.N. designed and developed the modified two-terminal all-perovskite tandem architecture. B.A.N. designed and fabricated the scalable all-perovskite tandem solar modules. E.A. provided the IO:H substrates. R. Schmager simulated the tandem solar cells. B.A.N., S.M. and H.H. developed the NBG perovskite solar cells. T.F. and H.H. developed and optimized the ALD deposition of the SnOx. T.F. contributed to the development of MgF2 thin films. F.S. and F.L. conducted the electroluminescence measurements. B.A.N. and F.S. modified the blade coating of the WBG perovskite. B.A.N. modified the blade coating of the NBG perovskite and charge transport layers. R. Singh encapsulated the modules. R.A. conducted the ToF-SIMS measurement. T.A. coordinated the laser scribing and ALD buffer development and gave technical support during the deposition of vacuum-processed charge transport layers. M.K. conducted the photoluminescence measurements. S.G. helped in developing the HTL layer in the top subcell. D.B.R. and H.H. had contributed equally. B.A.N., U.L., B.S.R. and U.W.P. concluded the discussion of the results. U.W.P. supervised the project. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Energy thanks Jérémie Werner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–7, Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–32.

Supplementary Video 1

EL imaging of the top and bottom subcells shows the EL with raising applied voltage, which corresponds to an increasing recombination current density.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 2.

Supplementary Data 2

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 5.

Supplementary Data 2

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 6.

Supplementary Data 3

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 8.

Supplementary Data 4

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 13.

Supplementary Data 5

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 15.

Supplementary Data 6

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 16.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdollahi Nejand, B., Ritzer, D.B., Hu, H. et al. Scalable two-terminal all-perovskite tandem solar modules with a 19.1% efficiency. Nat Energy 7, 620–630 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01059-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01059-w

This article is cited by

-

Perovskite–organic tandem solar cells

Nature Reviews Materials (2024)

-

Efficient SnS Solar Cells via Plasmonic Light Trapping and Alternative Buffer Layers: A Combined Machine Learning and FDTD Analysis

Plasmonics (2024)

-

Charge transport materials for monolithic perovskite-based tandem solar cells: A review

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Recent advances in developing high-performance organic hole transporting materials for inverted perovskite solar cells

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2022)