Abstract

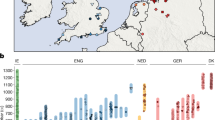

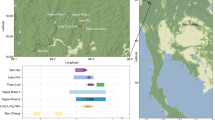

The Iron Age was a dynamic period in central Mediterranean history, with the expansion of Greek and Phoenician colonies and the growth of Carthage into the dominant maritime power of the Mediterranean. These events were facilitated by the ease of long-distance travel following major advances in seafaring. We know from the archaeological record that trade goods and materials were moving across great distances in unprecedented quantities, but it is unclear how these patterns correlate with human mobility. Here, to investigate population mobility and interactions directly, we sequenced the genomes of 30 ancient individuals from coastal cities around the central Mediterranean, in Tunisia, Sardinia and central Italy. We observe a meaningful contribution of autochthonous populations, as well as highly heterogeneous ancestry including many individuals with non-local ancestries from other parts of the Mediterranean region. These results highlight both the role of local populations and the extreme interconnectedness of populations in the Iron Age Mediterranean. By studying these trans-Mediterranean neighbours together, we explore the complex interplay between local continuity and mobility that shaped the Iron Age societies of the central Mediterranean.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All tools and data needed to reproduce and evaluate the conclusions in this paper are presented in the main text and the Supplementary Information. Alignment files for the DNA sequences for all newly reported individual genomes are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database under project accession number PRJEB49419.

References

López-Ruiz, C. & Doak, B. R. The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean (Oxford Univ. Press, 2019).

Quinn, J. C. & Vella, N. C. The Punic Mediterranean: Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Turfa, J. M. The Etruscan World (Routledge, 2014).

Benelli, E. in Italy and the West: Comparative Issues in Romanization (eds Keay, S. J. & Terrenato, N.) 7–16 (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2001).

Broodbank, C. The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Fernandes, D. M. et al. The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 334–345 (2020).

Marcus, J. H. et al. Genetic history from the Middle Neolithic to present on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia. Nat. Commun. 11, 939 (2020).

Antonio, M. L. et al. Ancient Rome: a genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean. Science 366, 708–714 (2019).

Posth, C. et al. The origin and legacy of the Etruscans through a 2000-year archeogenomic time transect. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7673 (2021).

Reitsema, L. J. et al. The diverse genetic origins of a Classical period Greek army. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205272119 (2022).

Matisoo-Smith, E. A. et al. A European mitochondrial haplotype identified in ancient Phoenician remains from Carthage, North Africa. PLoS ONE 11, e0155046 (2016).

Saupe, T. et al. Ancient genomes reveal structural shifts after the arrival of steppe-related ancestry in the Italian Peninsula. Curr. Biol. 31, 2576–2591.e12 (2021).

Haber, M. et al. A genetic history of the Near East from an aDNA time course sampling eight points in the past 4,000 years. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107, 149–157 (2020).

Haber, M. et al. Continuity and admixture in the last five millennia of levantine history from ancient Canaanite and present-day Lebanese genome sequences. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 274–282 (2017).

Olalde, I. et al. The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science 363, 1230–1234 (2019).

Zalloua, P. et al. Ancient DNA of Phoenician remains indicates discontinuity in the settlement history of Ibiza. Sci. Rep. 8, 17567–17515 (2018).

Schuenemann, V. J. et al. Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods. Nat. Commun. 8, 15694 (2017).

Villalba-Mouco, V. et al. Genomic transformation and social organization during the Copper Age–Bronze Age transition in southern Iberia. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7038 (2021).

Feldman, M. et al. Ancient DNA sheds light on the genetic origins of early Iron Age Philistines. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0061 (2019).

Agranat-Tamir, L. et al. The genomic history of the Bronze Age Southern Levant. Cell 181, 1146–1157.e11 (2020).

Fregel, R. et al. Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence prehistoric migrations to the Maghreb from both the Levant and Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6774–6779 (2018).

Patterson, N., Price, A. L. & Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2, e190 (2006).

Patterson, N. et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192, 1065–1093 (2012).

Harney, É., Patterson, N., Reich, D. & Wakeley, J. Assessing the performance of qpAdm: a statistical tool for studying population admixture. Genetics 217, iyaa045 (2021).

Fantar, M. H. in Fenicios y Territorio: Actas del II Seminario (ed. Prats, A. G.) 71–88 (Instituto Alicantino de Cultura Juan Gil-Albert Alfredo, 2000).

Fantar, M. H. Le cavalier marin de Kerkouane. Africa 1, 19–32 (1988).

Fantar, M. H. Kerkouane: Cité Punique du Cap Bon (Tunisie) (Institut National d’Archéologie et d’Art, 1984).

Miles, R. Carthage Must Be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization (Allen Lane, 2010).

Fantar, M. Espaces culturels à Kerkouane. C. R. Acad. Sci. Inscr. Belles Lett. 147, 817–824 (2003).

Fantar, M. H. Kerkouane: Une Cité Punique au Cap-Bon (Institut national d'archéologie et d'art, 1987).

Salas, A. et al. The making of the African mtDNA landscape. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1082–1111 (2002).

Lazaridis, I. et al. Genetic origins of the minoans and mycenaeans. Nature 548, 214–218 (2017).

Loogväli, E.-L. et al. Disuniting uniformity: a pied cladistic canvas of mtDNA haplogroup H in Eurasia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2012–2021 (2004).

Skourtanioti, E. et al. Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 290–303 (2023).

Hunter, V. Review of Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece: Representations and Realities by Pomeroy, S. B. Phoenix 52, 395–398 (1998).

Gallego Llorente, M. et al. Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture in eastern Africa. Science 350, 820–822 (2015).

Fregel, R. et al. Mitogenomes illuminate the origin and migration patterns of the indigenous people of the Canary Islands. PLoS ONE 14, e0209125 (2019).

Arauna, L. R. et al. Recent historical migrations have shaped the gene pool of Arabs and Berbers in North Africa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 318–329 (2017).

Matisoo-Smith, E. et al. Ancient mitogenomes of Phoenicians from Sardinia and Lebanon: a story of settlement, integration, and female mobility. PLoS ONE 13, e0190169 (2018).

Modi, A. et al. Genetic structure and differentiation from early Bronze Age in the Mediterranean island of Sicily: insights from ancient mitochondrial genomes. Front. Genet. 13, 945227 (2022).

Modi, A. et al. The mitogenome portrait of Umbria in Central Italy as depicted by contemporary inhabitants and pre-Roman remains. Sci. Rep. 10, 10700 (2020).

Aneli, S. et al. The genetic origin of Daunians and the pan-Mediterranean southern Italian Iron Age context. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac014 (2022).

Serventi, P. et al. Iron Age Italic population genetics: the Piceni from Novilara (8th–7th century BC). Ann. Hum. Biol. 45, 34–43 (2018).

Sarno, S. et al. Insights into Punic genetic signatures in the southern necropolis of Tharros (Sardinia). Ann. Hum. Biol. 48, 247–259 (2021).

Moorjani, P. et al. The history of African gene flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001373 (2011).

Koptekin, D. et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in human mobility patterns in Holocene Southwest Asia and the East Mediterranean. Curr. Biol. 33, 41–57.e15 (2023).

Antonio, M. L. et al. Stable population structure in Europe since the Iron Age, despite high mobility. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.15.491973 (2022).

Botigué, L. R. et al. Gene flow from North Africa contributes to differential human genetic diversity in southern Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11791–11796 (2013).

Fentress, E. in The Hellenistic West: Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean (eds Prag, J. & Quinn, J.) 157–178 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Sereno, P. C. et al. Lakeside cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 years of holocene population and environmental change. PLoS ONE 3, e2995 (2008).

Sommer, M. in Money, Trade and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa (eds Dowler, A. & Galvin, E. R.) 61–64 (British Museum, 2011).

Hérodote. Textes relatifs à l’histoire de l’Afrique du Nord. Hérodote [L. IV, ch. 168–199; l. II, ch. 31–33; l. IV, ch. 42–43], par Stéphane Gsell. [Texte, traduction, commentaire. Fragments d’Hécatée relatifs à la Libye.] (A. Jourdan, 1915).

Hodos, T. Colonial engagements in the global Mediterranean Iron Age. Camb. Archaeol. J. 19, 221–241 (2009).

Whittaker, C. R. in Imperialism in the Ancient World: The Cambridge University Research Seminar in Ancient History (eds Garnsey, P. & Whittaker, C.) 59–90 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1979).

Freund, K. P. A long-term perspective on the exploitation of Lipari obsidian in central Mediterranean prehistory. Quat. Int. 468, 109–120 (2018).

Pinhasi, R., Fernandes, D. M., Sirak, K. & Cheronet, O. Isolating the human cochlea to generate bone powder for ancient DNA analysis. Nat. Protoc. 14, 1194–1205 (2019).

Pinhasi, R. et al. Optimal ancient DNA yields from the inner ear part of the human petrous bone. PLoS ONE 10, e0129102 (2015).

Meyer, M. & Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, pdb.prot5448 (2010).

Renaud, G., Slon, V., Duggan, A. T. & Kelso, J. Schmutzi: estimation of contamination and endogenous mitochondrial consensus calling for ancient DNA. Genome Biol. 16, 224 (2015).

Allen Ancient DNA Resource: Downloadable Genotypes of Present-day and Ancient DNA Data (David Reich Lab, 2021); https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancient-dna-resource-aadr-downloadable-genotypes-present-day-and-ancient-dna-data (2021).

Mallick, S. et al. The Allen Ancient DNA Resource (AADR): a curated compendium of ancient human genomes. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.06.535797 (2023).

Kuhn, M., Manuel, J., Jakobsson, M. & Günther, T. Estimating genetic kin relationships in prehistoric populations. PLoS ONE 13, e0195491 (2018).

Maier, R. & Patterson, N. admixtools2 (Github, 2022).

ESRI. World Basemap v2. World Topographic Map (ArcGIS Online, 2017); https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=7dc6cea0b1764a1f9af2e679f642f0f5

Acknowledgements

This project was partially supported by the Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship (H.M.M.) and grants from the Stanford Archaeology Centre (H.M.M.), the Europe Center Austria Exchange Program (H.M.M.) and the Stanford Anthropology Department (H.M.M.), a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (M.A.), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) M3108-G (S.S.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.K.P.), a grant from the National Institutes of Health RO1 HG011432 (C.L.W.), the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (A.C., M.L., F.C., F.L.P., F.G.), the Istituto Per l’Oriente CA Nallino (A.C., M.L., F.C., F.L.P., F.G.), and a Ministro dell’Istruzione, Università e Ricerca (MIUR) project grant via the International Association for the Mediterranean and Oriental Studies (A.C., M.L., F.C., F.L.P., F.G.). We thank all members of the Pritchard and Pinhasi labs for their thoughtful and valuable feedback; P. W. Faber and the University of Chicago Genomics Facility for providing sequencing services for the ancient genomes reported here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P., J.K.P, A.C. and M.F. designed research; R.P., S.S., V.O., E.P., O.C., K.T.O., L.D., H.M.M. and D.F. performed and supervised laboratory work; A.C. and M.F. designed the collection strategy for archaeological material; M.F., A.C., M.L., F.L.P., F.G., F.C., D.D.A., G.G., H.M.M., Y.M.S.C. and S.A. assembled skeletal material and provided archaeological background; H.M.M., M.A., S.S., J.P.S., V.O., C.L.W., E.P., B.Z. and Z.G. curated and analysed data with input from J.K.P., R.P., A.C., D.F. and Y.M.S.C.; H.M.M., J.K.P., R.P., J.P.S., M.A., S.S., C.L.W., Y.M.S.C. and Z.G. wrote the paper with input from all collaborators.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Rosa Fregel, Josephine Crawley Quinn and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15, Discussion/Text, Table 1, and captions for Datasets 1–5.

Supplementary Data 1

Newly reported ancient individuals.

Supplementary Data 2

Ancient individual genomes used in analyses.

Supplementary Data 3

AMS dating and isotope analysis results.

Supplementary Data 4

Admixture and cladistic analysis using qpAdm and qpWave.

Supplementary Data 5

Admixture analysis using qpAdm, including Levantine source populations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Moots, H.M., Antonio, M., Sawyer, S. et al. A genetic history of continuity and mobility in the Iron Age central Mediterranean. Nat Ecol Evol 7, 1515–1524 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02143-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02143-4