Abstract

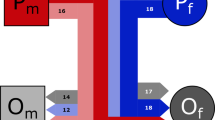

The human mutation rate per generation estimated from trio sequencing has revealed an almost linear relationship with the age of the father and the age of the mother, with fathers contributing about three times as many mutations per year as mothers. The yearly trio-based mutation rate estimate of around 0.43 × 10−9 is markedly lower than previous indirect estimates of about 1 × 10−9 per year from phylogenetic comparisons of the great apes calibrated by fossil evidence. This suggests either a slowdown in the accumulation of mutations per year in the human lineage over the past 10 million years or an inaccurate interpretation of the fossil record. Here we inferred de novo mutations in chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan parent-offspring trios. Extrapolating the relationship between the mutation rate and the age of parents from humans to these other great apes, we estimated that each species has higher mutation rates per year by factors of 1.50 ± 0.10, 1.51 ± 0.23, and 1.42 ± 0.22 for chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan, respectively, and by a factor of 1.48 ± 0.08 for the three species combined. These estimates suggest an appreciable slowdown in the yearly mutation rate in the human lineage that is likely to be recent as genome comparisons almost adhere to a molecular clock. If the nonhuman rates rather than the human rate are extrapolated over the phylogeny of the great apes, we estimate divergence and speciation times that are much more in line with the fossil record and the biogeography.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All sequence data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession number PRJEB29710. The identified de novo mutations are included as Supplementary Table 1. All scripts and code used to generate the results are available at https://github.com/besenbacher/GreatApeMutationRate2018.

Change history

15 April 2019

In the version of this article initially published, Tomas Marques-Bonet was missing the following affiliations: Catalan Institution of Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA), Barcelona, Spain; CNAG-CRG, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST), Barcelona, Spain; and Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. The affiliations have been added in the PDF and HTML versions of the article.

References

Maretty, L. et al. Sequencing and de novo assembly of 150 genomes from Denmark as a population reference. 548, 87–91 (2017).

Jónsson, H. et al. Parental influence on human germline de novo mutations in 1,548 trios from Iceland. Nature 549, 519–522 (2017).

Kong, A. et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature 488, 471–475 (2012).

Prüfer, K. et al. A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia. Science 358, 655–658 (2017).

Scally, A. The mutation rate in human evolution and demographic inference. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 41, 36–43 (2016).

Lipson, M. et al. Calibrating the human mutation rate via ancestral recombination density in diploid genomes. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005550 (2015).

Moorjani, P., Amorim, C. E., Arndt, P. F. & Przeworski, M. Variation in the molecular clock of primates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10607–10612 (2016).

Moorjani, P., Gao, Z. & Przeworski, M. Human germline mutation and the erratic evolutionary clock. PLoS Biol. 14, e2000744 (2016).

Scally, A. & Durbin, R. Revising the human mutation rate: implications for understanding human evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 745–753 (2012).

Scally, A. et al. Insights into hominid evolution from the gorilla genome sequence. Nature 483, 169–175 (2012).

Amster, G. & Sella, G. Life history effects on the molecular clock of autosomes and sex chromosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1588–1593 (2016).

Scally, A. Mutation rates and the evolution of germline structure. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 371, 20150137 (2016).

Venn, O. et al. Strong male bias drives germline mutation in chimpanzees. Science 344, 1272–1275 (2014).

Tatsumoto, S. et al. Direct estimation of de novo mutation rates in a chimpanzee parent–offspring trio by ultra-deep whole genome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 7, 13561 (2017).

Besenbacher, S. et al. Novel variation and de novo mutation rates in population-wide de novo assembled Danish trios. Nat. Commun. 6, 5969 (2015).

Moorjani, P. et al. A genetic method for dating ancient genomes provides a direct estimate of human generation interval in the last 45,000 years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5652–5657 (2016).

Gao, Z. et al. Overlooked roles of DNA damage and maternal age in generating human germline mutations. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/10/11/327098 (2018).

Goldmann, J. M. et al. Germline de novo mutation clusters arise during oocyte aging in genomic regions with high double-strand-break incidence. Nat. Genet. 50, 487–492 (2018).

Lindsay, S. J., Rahbari, R., Kaplanis, J., Keane, T. & Hurles, M. Striking differences in patterns of germline mutation between mice and humans. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/05/23/082297 (2018).

Jónsson, H. et al. Multiple transmissions of de novo mutations in families. Nat. Genet. 50, 1674–1680 (2018).

Thomas, G. W. C. et al. Reproductive longevity predicts mutation rates in primates. Curr. Biol. 28, 3193–3197 (2018).

White, T. D. et al. Ardipithecus ramidus and the paleobiology of early hominids. Science 326, 64–86 (2009).

Richmond, B. G. & Jungers, W. L. Orrorin tugenensis femoral morphology and the evolution of hominin bipedalism. Science 319, 1662–1665(2008).

Pilbeam, D., Rose, M. D., Barry, J. C. & Shah, S. M. New Sivapithecus humeri from Pakistan and the relationship of Sivapithecus and Pongo. Nature 348, 237–239 (1990).

Delehelle, F., Cussat-Blanc, S., Alliot, J.-M., Luga, H. & Balaresque, P. ASGART: fast and parallel genome scale segmental duplications mapping. Bioinformatics 34, 2708–2714 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Przeworski and P. Moorjani for comments to a previous version of the manuscript and A. Brandstrup for laboratory expertise. The study was supported by grant number 6108-00385A from the Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences (to M.H.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., T.M., T.M.-B., C.H., and M.H.S. designed the study. C.H. contributed reagents. S.B., T.M., and M.H.S. performed analysis. S.B. and M.H.S. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–6 and Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data file

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Besenbacher, S., Hvilsom, C., Marques-Bonet, T. et al. Direct estimation of mutations in great apes reconciles phylogenetic dating. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 286–292 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0778-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0778-x

This article is cited by

-

Comparative genomic analyses provide new insights into evolutionary history and conservation genomics of gorillas

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2024)

-

Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates

Nature (2023)

-

Ghost admixture in eastern gorillas

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Evolutionary dynamics of pseudoautosomal region 1 in humans and great apes

Genome Biology (2022)

-

Rainfall and sea level drove the expansion of seasonally flooded habitats and associated bird populations across Amazonia

Nature Communications (2022)