Abstract

We present programmable two-dimensional arrays of microscopic atomic ensembles consisting of more than 400 sites with nearly uniform filling and small atom number fluctuations. Our approach involves direct projection of light patterns from a digital micromirror device with high spatial resolution onto an optical pancake trap acting as a reservoir. This makes it possible to load large arrays of tweezers in a single step with high occupation numbers and low power requirements per tweezer. Each atomic ensemble is confined to ~1 μm3 with a controllable occupation from 20 to 200 atoms and with (sub)-Poissonian atom number fluctuations. Thus, they are ideally suited for quantum simulation and for realizing large arrays of collectively encoded Rydberg-atom qubits for quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neutral atoms in optical tweezer arrays have emerged as one of the most versatile platforms for quantum many-body physics, quantum simulation, and quantum computation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. This is largely due to their long coherence times combined with flexible configurations and controllable long-range interactions, in particular using highly excited Rydberg states11,12,13,14,15,16,17. To date, substantial experimental efforts have been devoted to create fully occupied atomic arrays with ≃1 atom in each tweezer by exploiting light-assisted inelastic collisions18,19,20 and rearrangement to fill empty sites4,5,21,22,23,24. In combination with high-fidelity Rydberg blockade gates16,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, these systems have been recently used to demonstrate coherent quantum dynamics of up to 51 qubits32 and entangled states of up to 20 qubits in one-dimensional (1D) chains33. So far however, achievable array sizes are limited to ≲100 fully occupied sites (including for 2D and 3D systems), in part due to high power requirements and increasing complexity associated with the rearrangement process for larger arrays21,23,24.

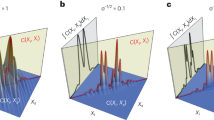

In this paper, we demonstrate an alternative approach to prepare large and uniformly filled arrays of hundreds of tweezers with large occupation numbers in a single step. This is exemplified by the 400 site triangular array shown in Fig. 1a, as well as more exotic geometries, such as connected rings (Fig. 1b) and quasi-ordered geometries (Fig. 1c), which exhibit structures on different length scales making them difficult to produce using other methods. Our approach involves transferring ultracold atoms from a quasi-2D optical reservoir trap into an array of optical tweezers produced by a digital micromirror device (DMD). To realize large arrays we optimize the loading process and the homogeneity across the lattice by adapting the DMD light patterns to control the trap depth of each tweezer. Each atomic ensemble is localized well within the typical Rydberg blockade radius, and the typical intertrap separations of several micrometers are compatible with Rydberg-blockade gates. Furthermore, we show that the fluctuations of the number of atoms in each tweezer is comparable to, or below the shot-noise limit for uncorrelated atoms. These properties make the system well suited for quantum simulation of quantum spin models13,14,17,34,35,36,37,38,39 and dynamics40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 in novel geometries, as well as for realizing quantum registers with collectively enhanced atom–light interactions for quantum information processing11,36,48,49,50,51.

a Experimental absorption image of a 400 site triangular lattice, where each dark spot corresponds to a microscopic ensemble of ≈30 ultracold 39K atoms. The lattice spacing is 4 μm and the apparent size of each spot is ~0.75 μm (e−1/2 radius), mostly limited by recoil blurring during imaging. b 40 site ring structure and c 226 site Penrose quasicrystal lattice. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio each image is an average of 20 absorption images. In a–c the length of scale bars is equal to 10 μm. d Setup used to produce and load the tweezer arrays by projecting light from a digital micromirror device directly onto the atoms confined in an optical reservoir trap.

Results

Our experimental cycle starts with a three-dimensional magneto-optical trap (MOT) loaded from a beam of 39K atoms produced by a two-dimensional MOT. This is overlapped with a far off-resonant pancake-shaped reservoir trap created by a 1064 nm single mode laser with a power of 16 W tightly focused by a cylindrical lens. The beam waists are ωz = 7.6 μm, ωx = 540 μm, and ωy = 190 μm and the estimated trap depth is 330 μK. To maximize the number of atoms in the reservoir we apply an 8 ms gray-molasses cooling stage on the D1 transition52, yielding 3.3 × 105 atoms in the \(\left|4{s}_{1/2},F=1\right\rangle\) state at an initial temperature of 45 μK.

Next, we transfer the atoms to the tweezers from the reservoir trap. To generate the tweezers we illuminate a DMD with a collimated 780 nm Gaussian beam of light with a 4.3 mm waist and a peak intensity of 1.44 W cm−2. We directly image the DMD plane onto the atoms (similar optical setup to refs. 53,54) with a calibrated demagnification factor of 53, using a 4f optical setup involving a 1500 mm focal length lens and a 32 mm focal length lens (Fig. 1d). The latter is a molded aspheric lens with a numerical aperture of 0.6, located inside the vacuum chamber. With this setup, each (13 μm)2 pixel of the DMD corresponds to (245 nm)2 in the atom plane.

The DMD can be programmed with arbitrary binary patterns to control the illumination in the atom plane. To generate the tweezer arrays shown in Fig. 1a–c we create different patterns of spots where each spot is formed by a small disk-shaped cluster of typically A = 20–100 pixels. To detect the atoms we use the saturated absorption imaging technique55,56. The probe laser is resonant to the 4s1/2 → 4p3/2 transition of 39K at 767 nm and with an intensity of \(I\approx 2.1{I}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}\). The atoms are exposed for 10 μs and the absorption shadow is imaged onto a charge-coupled-device camera using the same optics as for the DMD light patterns (Fig. 1d). The resulting optical depth image is well described by a sum of two-dimensional Gaussian distributions. By fitting and integrating each distribution we determine the number of atoms in each tweezer. By analyzing a background region of the images we infer a single-shot detection sensitivity of 3.9(5) atoms.

We found that optimal loading of the tweezers is achieved by evaporatively cooling the atoms in the reservoir trap while superimposing the DMD light pattern (Fig. 2a). At the end of the evaporation ramp the reservoir trap can be switched off leaving the atoms confined by the tweezers alone. The overall cycle time including MOT loading, evaporative cooling, transfer to the tweezers and imaging is <4 s. Figure 2b, c show the characterization of the loading process for a single tweezer with A = 100 pixels, corresponding to an optical power of 90 μW. There is little difference if the tweezer is switched on suddenly or ramped slowly, however we found it is beneficial to turn on the tweezers at least 200 ms before the end of the evaporation ramp (Fig. 2b), indicating a significant enhancement of the loading through elastic collisions with the reservoir atoms57. Figure 2c shows that the mean occupation number \(\bar{N}={\langle N\rangle }_{i}\) (with \({\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle }_{i}\) denoting an average over different experimental realizations) strongly depends on the final temperature of the reservoir, with the maximal \(\bar{N}=120(5)\) found for \({T}_{{\rm{res}}}\approx 2\) μK. The temperature of the atoms measured using the time-of-flight method for a single tweezer with A = 100 pixels, corresponding to a relatively deep trap, is 17(1) μK. Figure 2d shows the lifetime of the atoms in the tweezer. An exponential fit describing pure one-body decay (dashed curve) is clearly ruled out by the data while a model which includes both three-body and one-body decay58 provides an excellent fit (solid curve). From this model we extract both the three-body and one-body decay constants \({k}_{3}^{-1}=110\ {\rm{ms}}\), \({k}_{1}^{-1}=3100\ {\rm{ms}}\), which are both orders of magnitude longer than typical timescales in Rydberg atom experiments.

a Sketch of the experimental sequence used to load the tweezers. b Mean occupation number in a single tweezer as a function of the overlap time τ between the end of the reservoir evaporation ramp and the turning on of the tweezer. For τ ≈ 200 ms the occupation number reaches its maximum value of \(\bar{N}=120\). c Mean occupation and two-dimensional density of atoms in the reservoir as a function of the reservoir temperature after evaporation. Optimal loading is achieved for a final reservoir temperature of 2 μK, which is a compromise between temperature and the remaining density of atoms in the reservoir. d Measurement of the lifetime of atoms held in the tweezer. The solid line is a fit to a model accounting for one-body and three-body loss processes, while the dashed line is an exponential fit assuming one-body loss only. In b–d the error bars depict the standard deviation over three experimental repetitions.

We now show that it is straightforward to scale up to a large number of sites while maintaining a uniformly high occupation of each tweezer. For arrays with more than approximately M = (10 × 10) sites we found it is beneficial to adapt the DMD pattern to compensate the Gaussian illumination profile. We adapt the number of pixels in each cluster according to its distance from the center of the illumination region following an inverted Gaussian dependence \({A}_{m}={A}_{\min }\exp (g{r}_{m}^{2})\) where m indexes a tweezer at position rm in the DMD plane. The parameters \({A}_{\min }=20\) pixels and g = 2.3 × 10−5 were manually adapted to obtain approximately equal optical depths for each tweezer, where \({A}_{\min }=20\) pixels corresponds to an optical power per tweezer of 18 μW. The maximum array size of M = (22 × 22) was fixed such that \(\max ({A}_{m})=66\) pixels, due to larger spots increasing the apparent size of the atomic ensembles near the edge of the array. Once the optimal compensation profile is found it can be applied to different geometries without further adjustment.

Figure 3 shows the mean occupation number \(\bar{N}\) for square arrays with different numbers of sites. The solid orange symbols show the array averaged mean occupation number \({\langle \bar{N}\rangle }_{m}\), where we average over all 20 experimental repetitions and each lattice site m. The experiments show that \({\left\langle \bar{N}\right\rangle }_{m}\simeq 40\) is approximately constant for tweezer arrays with different numbers of sites 4 ≤ M ≤ 484. As an example, for M = 400 the standard deviation is \(0.17{\left\langle \bar{N}\right\rangle }_{m}\) (excluding shot-to-shot fluctuations), compared to \(0.55{\langle \bar{N}\rangle }_{m}\) without compensation. The uniformity could be further improved by adapting Am for each tweezer individually, but it is already better than the expected intrinsic shot-to-shot fluctuations of the atom number in each site due to atom shot-noise (with standard deviation \(\sqrt{\bar{N}}\)) for \(\bar{N}\lesssim 36\).

The square data points show the array-averaged mean occupation number for square arrays with a period of 3.5 μm and different numbers of sites ranging from M = 2 × 2 to M = 22 × 22. Over this range the array averaged occupation number \({\langle \bar{N}\rangle }_{m}\approx 40\) is mostly homogeneous and insensitive to the number of tweezers. The shaded region represents the uniformity of each array, computed as the standard deviation of the mean occupation number. The insets show exemplary absorption images for four different sized arrays, each averaged over 20 experimental repetitions.

The apparent size of each atomic ensemble, found by analyzing the averaged absorption images, ranges from 0.64 μm near the center of the field to 0.93 μm at the edges (e−1/2 radii of each absorption spot). This can be understood as a convolution of several effects, the most important are recoil blurring, the finite resolution of the imaging system including off axis blurring and the finite size of each DMD spot. By projecting the DMD light pattern onto a camera in an equivalent test setup we independently determine the beam waist of each tweezer to be 0.9 μm. Assuming each tweezer is described by a Gaussian beamlet and approximating the atomic cloud by a thermal gas with a temperature ~V0/5 (with trap depth V0), we infer a cloud size of σr,z = {0.2, 1.0} μm. This is reasonably close to an independent estimate \(\root{3}\of{{\sigma _r^2{\sigma _z}}} \approx 0.6\) μm based on the experimentally measured three-body loss rate and a theoretical calculation of the zero field three-body loss coefficient for 39K59.

The small spatial extent of each ensemble is encouraging for experiments which aim to prepare a single Rydberg excitation at each site, as it is significantly smaller than the nearest-neighbor distance and the typical Rydberg blockade radius of Rbl ~ 3–6 μm (corresponding ns1/2 Rydberg states with principal quantum number n between 40 and 60). Approximating the density distribution as quasi-1D we estimate the weighted-average fraction of blockaded atoms, assuming random initial positions, as \({f}_{\mathrm {{bl}}}={\rm{erf}}({R}_{\mathrm {{bl}}}/2{\sigma }_{z})\), where \({\rm{erf}}(x)\) is the Gauss-error function. For Rbl/σz ≥ 3, fbl ≥ 0.97 which suggests that the blockade condition within a single tweezer should be well satisfied. To serve as effective two-level systems (comprised of the collective ground state and the state with a single Rydberg excitation shared amongst all atoms in the ensemble), it is additionally important that the fluctuations of the atom number from shot-to-shot are relatively small otherwise the \(\sqrt{{N}_{i}}\) collective coupling49,60,61 will reduce the single atom excitation fidelity when averaging over different realizations. Previous theoretical estimates have assumed Poisson distributed atom shot-noise36, which we generalize to the case of a stretched Poissonian distribution and imperfect blockade. However, we neglect other possible imperfections such as spectral broadening due to laser linewidth or interactions between ground state and Rydberg atoms36. For a simple estimate, we assume that within the blockade volume, the probability to create a single excitation undergoes collective Rabi oscillations \({p}_{i}=1-{\cos }^{2}(\sqrt{{N}_{i}}\Omega t/2)\) where Ω is the single atom Rabi frequency36. In contrast, the non-blockaded fraction of atoms 1 − fbl undergoes Rabi oscillations at the frequency Ω. By expanding around the time for a collective π pulse: \(t=\pi /(\sqrt{\bar{N}}\Omega )\) and averaging over a stretched Poissonian statistical distribution for atom number fluctuations we find that the infidelity for producing exactly one excitation is \(\epsilon \approx ({\pi }^{2}/4)[{\rm{var}}(N)/(4{\bar{N}}^{2})+(1-{f}_{\mathrm {{bl}}})]\). For fbl → 1 the infidelity is proportional to the relative variance \({\rm{var}}(N)/{\bar{N}}^{2}\).

To estimate the relative variance of the atom number fluctuations we prepare tweezer arrays with different numbers of sites and trap depths, corresponding to mean occupation numbers from \(\bar{N}=20\) to \(\bar{N}=200\). For each set of experimental conditions we take 20 absorption images from which we compute the mean occupation and the variance of the atom number in each tweezer. Figure 4 shows the relative variance \({\rm{var}}(N)/{\bar{N}}^{2}\) calculated for 75,880 tweezer realizations. We see that for smaller atom numbers the relative variance is consistent with the expected Poissonian atom-shot noise for independent particles \({\rm{var}}(N)=\bar{N}\) (shown by the solid black line), while for \(\bar{N}\,\gtrsim \,50\) the fluctuations are sub-Poissonian, reaching the lower limit expected for three-body loss (\({\rm{var}}(N)=0.6\bar{N}\), shown by the dashed black line)58. For \(\bar{N}\,>\,40\) the expected infidelity due to atom number fluctuations would be below 0.03, showing that this system should be compatible with high fidelity preparation of individual Rydberg excitations and quantum logic gates, and could still be further improved using adiabatic or composite pulse techniques48. Precise coherent manipulations of collective qubits could also be achieved by measuring the number of atoms in each ensemble and adapting the excitation pulses accordingly62.

The blue points show the relative variance computed from 20 repetitions of the experiment and for different mean occupation numbers. The black symbols show the same data after binning, where the bin widths are indicated by the horizonal red bars. The vertical error-bars show the standard error computed over the values inside each bin multiplied by a scaling factor of 10 for better visibility. The solid black line is a prediction assuming Poissonian atom number fluctuations \({\rm{var}}(N)/{\bar{N}}^{2}=1/\bar{N}\) and the dashed black line is a prediction assuming sub-Poissonian atom number fluctuations \({\rm{var}}(N)/{\bar{N}}^{2}=0.6/\bar{N}\).

Discussion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated an approach for realizing hundreds of ultracold atomic ensembles in programmable two-dimensional arrays, where each tweezer has approximately uniform filling, small spatial extent and small fluctuations of the atom number between realizations. Compared to stochastic loading of the tweezers via light-assisted collisions from a MOT, this has several advantages. First, it is possible to achieve very high occupation numbers N ≫ 1 with relatively low power requirements per tweezer, since the temperature of the initial reservoir trap can be lower than the typical temperatures in a MOT and elastic, rather than inelastic, collisions lead to a high filling probability. This is beneficial for scaling up to hundreds or even thousands of tweezers as the large volume of the reservoir trap makes it possible to simultaneously fill many tweezers in parallel without the need for additional lasers and complex rearrangement protocols to fill empty sites. Atomic ensembles also offer greater robustness against particle loss, since the loss of one or several particles from each microtrap does not result in defects that would otherwise be difficult to repair. Additionally, atomic ensembles present the possibility to evaporatively cool the atoms in each tweezer to reach high phase space densities or as a more controlled starting point for quasi-deterministic single atom preparation schemes using controlled inelastic collisions19,23 or the Rydberg blockade effect36,63,64. The observation that the number of atoms inside each tweezer exhibits fluctuations below the Poissonian atom shot-noise limit is especially promising for quantum information processing based on small Rydberg blockaded atomic ensembles benefiting from fast collectively enhanced light-matter couplings11,36,50,51,63.

Methods

The methods used to generate the optical tweezer arrays and to load them are described in the first half of “Results“ section. The methods used to characterize the atomic ensembles are described in the second half of “Results“ section.

Data availability

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dumke, R. et al. Micro-optical realization of arrays of selectively addressable dipole traps: a scalable configuration for quantum computation with atomic qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 097903 (2002).

Bergamini, S. et al. Holographic generation of microtrap arrays for single atoms by use of a programmable phase modulator. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 21, 1889–1894 (2004).

Nogrette, F. et al. Single-atom trapping in holographic 2D arrays of microtraps with arbitrary geometries. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021034 (2014).

Barredo, D., de Léséleuc, S., Lienhard, V., Lahaye, T. & Browaeys, A. An atom-by-atom assembler of defect-free arbitrary two-dimensional atomic arrays. Science 354, 1021–1023 (2016).

Endres, M. et al. Atom-by-atom assembly of defect-free one-dimensional cold atom arrays. Science 354, 1024–1027 (2016).

Kim, H. et al. In situ single-atom array synthesis using dynamic holographic optical tweezers. Nat. Commun. 7, 13317 (2016).

Tamura, H., Unakami, T., He, J., Miyamoto, Y. & Nakagawa, K. Highly uniform holographic microtrap arrays for single atom trapping using a feedback optimization of in-trap fluorescence measurements. Opt. Express 24, 8132–8141 (2016).

Norcia, M. A., Young, A. W. & Kaufman, A. M. Microscopic control and detection of ultracold Strontium in optical-tweezer arrays. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041054 (2018).

Cooper, A. et al. Alkaline-earth atoms in optical tweezers. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041055 (2018).

Anderegg, L. et al. An optical tweezer array of ultracold molecules. Science 365, 1156–1158 (2019).

Saffman, M. Quantum computing with atomic qubits and Rydberg interactions: progress and challenges. J. Phys. B 49, 202001 (2016).

Labuhn, H. et al. Tunable two-dimensional arrays of single Rydberg atoms for realizing quantum Ising models. Nature 534, 667–670 (2016).

Lienhard, V. et al. Observing the space- and time-dependent growth of correlations in dynamically tuned synthetic Ising models with antiferromagnetic interactions. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021070 (2018).

Guardado-Sanchez, E. et al. Probing the quench dynamics of antiferromagnetic correlations in a 2D quantum Ising spin system. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021069 (2018).

Kim, H., Park, Y., Kim, K., Sim, H.-S. & Ahn, J. Detailed balance of thermalization dynamics in Rydberg-atom quantum simulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 180502 (2018).

Graham, T. M. et al. Rydberg-mediated entanglement in a two-dimensional neutral atom qubit array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 230501 (2019).

de Léséleuc, S. et al. Observation of a symmetry-protected topological phase of interacting bosons with Rydberg atoms. Science 365, 775–780 (2019).

Schlosser, N., Reymond, G., Protsenko, I. & Grangier, P. Sub-Poissonian loading of single atoms in a microscopic dipole trap. Nature 411, 1024–1027 (2001).

Grünzweig, T., Hilliard, A., McGovern, M. & Andersen, M. F. Near-deterministic preparation of a single atom in an optical microtrap. Nat. Phys. 6, 951–954 (2010).

Lester, B. J., Luick, N., Kaufman, A. M., Reynolds, C. M. & Regal, C. A. Rapid production of uniformly filled arrays of neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 073003 (2015).

Barredo, D., Lienhard, V., de Léséleuc, S., Lahaye, T. & Browaeys, A. Synthetic three-dimensional atomic structures assembled atom by atom. Nature 561, 79–82 (2018).

Kumar, A., Wu, T.-Y., Giraldo, F. & Weiss, D. S. Sorting ultracold atoms in a three-dimensional optical lattice in a realization of Maxwell’s demon. Nature 561, 83–87 (2018).

Brown, M. O., Thiele, T., Kiehl, C., Hsu, T.-W. & Regal, C. A. Gray-molasses optical-tweezer loading: controlling collisions for scaling atom-array assembly. Phys. Rev. X 9, 011057 (2019).

Ohl de Mello, D. et al. Defect-free assembly of 2D clusters of more than 100 single-atom quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 203601 (2019).

Lukin, M. D. et al. Dipole blockade and quantum information processing in mesoscopic atomic ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 037901 (2001).

Isenhower, L. et al. Demonstration of a neutral atom controlled-NOT quantum gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010503 (2010).

Wilk, T. et al. Entanglement of two individual neutral atoms using Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 010502 (2010).

Maller, K. M. et al. Rydberg-blockade controlled-NOT gate and entanglement in a two-dimensional array of neutral-atom qubits. Phys. Rev. A 92, 022336 (2015).

Zeng, Y. et al. Entangling two individual atoms of different isotopes via Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 160502 (2017).

Levine, H. et al. High-fidelity control and entanglement of Rydberg-atom qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 123603 (2018).

Levine, H. et al. Parallel implementation of high-fidelity multiqubit gates with neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 170503 (2019).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017).

Omran, A. et al. Generation and manipulation of Schrödinger cat states in Rydberg atom arrays. Science 365, 570–574 (2019).

Glaetzle, A. W. et al. Quantum spin-ice and dimer models with Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041037 (2014).

van Bijnen, R. M. W. & Pohl, T. Quantum magnetism and topological ordering via Rydberg dressing near Förster resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 243002 (2015).

Whitlock, S., Glaetzle, A. W. & Hannaford, P. Simulating quantum spin models using Rydberg-excited atomic ensembles in magnetic microtrap arrays. J. Phys. B 50, 074001 (2017).

Kiffner, M., O’Brien, E. & Jaksch, D. Topological spin models in Rydberg lattices. Appl. Phys. B 123, 46 (2017).

Letscher, F., Petrosyan, D. & Fleischhauer, M. Many-body dynamics of holes in a driven, dissipative spin chain of Rydberg superatoms. N. J. Phys. 19, 113014 (2017).

Zeiher, J. et al. Coherent many-body spin dynamics in a long-range interacting Ising chain. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041063 (2017).

Günter, G. et al. Observing the dynamics of dipole-mediated energy transport by interaction-enhanced imaging. Science 342, 954–956 (2013).

Robicheaux, F. & Gill, N. M. Effect of random positions for coherent dipole transport. Phys. Rev. A 89, 053429 (2014).

Barredo, D. et al. Coherent excitation transfer in a spin chain of three Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 113002 (2015).

Schempp, H., Günter, G., Wüster, S., Weidemüller, M. & Whitlock, S. Correlated exciton transport in Rydberg-dressed-atom spin chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 093002 (2015).

Schönleber, D. W., Eisfeld, A., Genkin, M., Whitlock, S. & Wüster, S. Quantum simulation of energy transport with embedded Rydberg aggregates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 123005 (2015).

Płodzień, M., Sowiński, T. & Kokkelmans, S. Simulating polaron biophysics with Rydberg atoms. Sci. Rep. 8, 9247 (2018).

Whitlock, S., Wildhagen, H., Weimer, H. & Weidemüller, M. Diffusive to nonergodic dipolar transport in a dissipative atomic medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 213606 (2019).

Yang, F., Yang, S. & You, L. Quantum transport of Rydberg excitons with synthetic spin-exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 063001 (2019).

Beterov, I. I. et al. Quantum gates in mesoscopic atomic ensembles based on adiabatic passage and Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. A 88, 010303 (2013).

Ebert, M., Kwon, M., Walker, T. G. & Saffman, M. Coherence and Rydberg blockade of atomic ensemble qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 093601 (2015).

Brion, E., Mølmer, K. & Saffman, M. Quantum computing with collective ensembles of multilevel systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 260501 (2007).

Wintermantel, T. M. et al. Unitary and nonunitary quantum cellular automata with Rydberg arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 070503 (2020).

Salomon, G. et al. Gray-molasses cooling of 39K to a high phase-space density. EPL 104, 63002 (2013).

Muldoon, C. et al. Control and manipulation of cold atoms in optical tweezers. N. J. Phys. 14, 073051 (2012).

Gauthier, G. et al. Direct imaging of a digital-micromirror device for configurable microscopic optical potentials. Optica 3, 1136–1143 (2016).

Reinaudi, G., Lahaye, T., Wang, Z. & Guéry-Odelin, D. Strong saturation absorption imaging of dense clouds of ultracold atoms. Opt. Lett. 32, 3143–3145 (2007).

Ockeloen, C. F., Tauschinsky, A. F., Spreeuw, R. J. C. & Whitlock, S. Detection of small atom numbers through image processing. Phys. Rev. A 82, 061606 (2010).

Comparat, D. et al. Optimized production of large Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 73, 043410 (2006).

Whitlock, S., Ockeloen, C. F. & Spreeuw, R. J. C. Sub-poissonian atom-number fluctuations by three-body loss in mesoscopic ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 120402 (2010).

Esry, B. D., Greene, C. H. & Burke, J. P. Recombination of three atoms in the ultracold limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1751 (1999).

Dudin, Y. O., Li, L., Bariani, F. & Kuzmich, A. Observation of coherent many-body Rabi oscillations. Nat. Phys. 8, 790–794 (2012).

Zeiher, J. et al. Microscopic characterization of scalable coherent Rydberg superatoms. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031015 (2015).

Petrosyan, D. & Nikolopoulos, G. M. Assessing the number of atoms in a Rydberg-blockaded mesoscopic ensemble. Phys. Rev. A 89, 013419 (2014).

Ebert, M. et al. Atomic Fock state preparation using Rydberg blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 043602 (2014).

Weber, T. M. et al. Mesoscopic Rydberg-blockaded ensembles in the superatom regime and beyond. Nat. Phys. 11, 157-161 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the ‘Investissements d’Avenir’ program through the Excellence Initiative of the University of Strasbourg (IdEx), the University of Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Study (USIAS) and is part of and supported by the DFG Collaborative Research Center ‘SFB 1225 (ISOQUANT)’. S.S., T.M.W., and M.M. acknowledge the French National Research Agency (ANR) through the Program d’Investissement d’Avenir under contract ANR-17-EURE-0024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and S.S. performed experiments. T.M.W., G.L., and M.M. made contributions to the experimental setup. Y.W., S.S., and S.W. analyzed the data. Y.W. and S.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Shevate, S., Wintermantel, T.M. et al. Preparation of hundreds of microscopic atomic ensembles in optical tweezer arrays. npj Quantum Inf 6, 54 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-0285-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-0285-1

This article is cited by

-

Quantized valley Hall response from local bulk density variations

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Epidemic growth and Griffiths effects on an emergent network of excited atoms

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Review paper: imaging lidar by digital micromirror device

Optical Review (2020)