Abstract

Atomic-scale defects generated in materials under both equilibrium and irradiation conditions can significantly impact their physical and mechanical properties. Unraveling the energetically most favorable ground-state configurations of these defects is an important step towards the fundamental understanding of their influence on the performance of materials ranging from photovoltaics to advanced nuclear fuels. Here, using fluorite-structured thorium dioxide (ThO2) as an exemplar, we demonstrate how density functional theory and machine learning interatomic potential can be synergistically combined into a powerful tool that enables exhaustive exploration of the large configuration spaces of small point defect clusters. Our study leads to several unexpected discoveries, including defect polymorphism and ground-state structures that defy our physical intuitions. Possible physical origins of these unexpected findings are elucidated using a local cluster expansion model developed in this work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When crystalline materials are exposed to irradiation by energetic particles, point defects and their atomic-scale clusters will be generated in amounts significantly exceeding their equilibrium concentrations. Despite being largely hidden under high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM), these small irradiation-induced defects can drastically affect material properties through mechanisms such as dislocation pinning1 and phonon scattering2,3. Remarkably, a recent study by Zheng et al.4 showed that irradiation hardening in helium-implanted tungsten mainly originates from TEM-invisible point-defect complexes. Furthermore, Chauhan et al.5 demonstrated that the reduction in thermal conductivity in proton-irradiated ceria at lower temperatures is primarily due to point defects rather than TEM-detectable dislocation loops. These findings highlight the importance of having a fundamental understanding of the nature and concentrations of atomic-scale defects when making quantitative predictions of the impact of radiation on properties of materials such as nuclear fuels2. It is worth mentioning that, even under equilibrium conditions, the photovoltaic efficiency of solar cells can be intricately controlled by minute concentrations of point defects therein, which can act as traps for charge carriers such as electrons and holes6.

To overcome the experimental limitations in direct characterization of atomic-scale defects, one promising approach is to employ multiscale modeling that integrates computational techniques such as ab initio calculations based on density functional theory (DFT), kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) simulations7,8,9,10,11, and cluster dynamics (CD)11 to provide quantitative insights into the evolution of TEM-invisible defects under irradiation. However, such multiscale modeling presents its own challenges. For these simulations, accurate knowledge of the ground-state (GS) defect geometries is crucial since many defect properties (e.g., energetics and migration barriers) are closely tied to their structures. For instance, in bcc metals such as V and Nb, where the <111> dumbbell is the GS configuration of self-interstitial atom (SIA), the SIA will exhibit rapid one-dimensional (1D) migration10. Conversely, when the <110> dumbbell becomes the GS structure for SIA, as seen in bcc Fe7, it will exhibit slow three-dimensional (3D) diffusion. It is noteworthy that precise knowledge of the GS structures of TEM-invisible defects in solar cells is also essential for accurately predicting their impact on photovoltaic efficiency6. Finding the GS structures of point defects and their clusters, however, is a daunting global optimization task that necessitates a thorough exploration of their complex potential energy surfaces (PESs)6,12,13. With increasing defect cluster size, the complexity of defect PESs tends to grow exponentially, quickly making a DFT-driven GS search computationally infeasible even with modern supercomputers.

Motivated by recent successes in using machine learning to predict defect behavior12,14 as well as the structures of nanoclusters15 and solid surfaces16, here we address the computational challenge of determining the GSs of defect clusters embedded in large supercells by employing a predictive machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP)17,18 to conduct the initial screening of defect structures. Energetically favorable candidate structures identified by MLIP are then reoptimized using accurate DFT calculations. By directly learning from large DFT datasets without assuming any fixed functional forms, a MLIP can reproduce DFT PESs far more accurately than an empirical potential. This increased level of fidelity is particularly crucial, as empirical potential-driven GS searches have been known to yield results that do not agree with DFT12,13. Additionally, a MLIP is many orders of magnitude faster than DFT, since it does not treat electrons explicitly.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the combined DFT and MLIP approach, we applied it to predict the GSs of small interstitial and vacancy clusters in irradiated ThO2. Besides being a candidate fuel for advanced nuclear reactors, ThO2 does not contain 5 f electrons, making it a good surrogate material for enabling investigations of physical properties without the complication of strong electron correlation found in other actinide oxides2,3.

Results

Training the machine learning interatomic potential

To train a MLIP for defect-containing ThO2, we performed high-throughput DFT calculations to construct a large database that extensively samples a wide range of local atomic environments that are potentially encountered during irradiation. Our DFT training database includes the crystalline fluorite structure with different types of radiation-induced defects (e.g., vacancies, interstitials, and voids) as well as liquid ThO2 structures, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. To sample the portion of the PES near equilibrium that is accessible through finite temperature lattice vibrations, we further incorporated structures taken directly from snapshots of long-time ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. In total, our DFT database is comprised of 3,672 total energies and 3,521,988 atomic forces. A neural network-based MLIP for ThO2 was trained using the n2p2 code19,20, which employs atom-centered radial and angular symmetry functions to create a “fingerprint” of the local environment surrounding an atom that can capture rotational, permutation, and translational symmetries. For both Th and O atom types, the neural network has two hidden layers, each consisting of 21 neurons. The input layer size is 41 and 46 for Th and O atoms, respectively. The cutoff radii for radial and angular symmetry functions are 10 Å and 6 Å, respectively. The networks for Th and O were simultaneously trained using a supervised learning approach, minimizing the loss function defined as the sum of mean squared errors for energy and force. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, our MLIP accurately reproduces both training and testing DFT data, exhibiting a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of only 3.3 meV per atom for total energy and 0.18 eV Å-1 for force. Our MLIP also predicts properties of ThO2, such as equilibrium lattice parameter, single-crystal elastic constants, as well as defect formation and migration energies, in good agreement with DFT calculations (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that in the neural network potential19, the total energy of a system is approximated as a sum of energies of individual atoms, which only depend on their local environments. Terms accounting for long-range interactions are therefore not explicitly included in its formalism. Despite this locality assumption, our study demonstrates that short-ranged MLIPs can yield sufficient accuracy for modeling ionic materials such as ThO2, especially with the help of a large cutoff radius for symmetry functions. The remarkable accuracy of MLIPs for ionic materials has also been discussed in a recent study by Staacke et al.21

Searching for ground-state structures

Using our developed MLIP as a surrogate model for DFT, we exhaustively examined many possible configurations of small defect clusters in ThO2. Specifically, we considered interstitial-type clusters (mThi + nOi) and vacancy-type clusters (mVaTh + nVaO), with m ranging from 2 to 4 and n being less than or equal to 12. Here Thi, Oi, VaTh, and VaO refer to thorium interstitial, oxygen interstitial, thorium vacancy, and oxygen vacancy, respectively. We systematically enumerated all symmetrically distinct configurations for mThi + nOi clusters, with the m Thi and n Oi defects being placed in neighboring octahedral interstitial sites in ThO2. In each configuration, we ensured that every Oi is close to at least one Thi defect. Similarly, we thoroughly examined all possible arrangements of n VaO defects around m VaTh defects in mVaTh + nVaO complexes, ensuring that there is at least one VaTh close to a VaO defect. For the charge-neutral 4Thi + 8Oi interstitial cluster, we further considered the experimentally observed Frank loop configuration8, which involves the insertion of a planar monolayer of Th interstitials, positioned between two layers of Oi, all aligned parallel to the {111} plane. This effectively creates a stacking fault within the ThO2 lattice. All defect configurations considered in our GS searches are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 4. The number of configurations sampled for each defect cluster type is summarized in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5. In total, we used MLIP to perform structural optimizations of 10,557,845 distinct configurations, out of which approximately 600 energetically competitive structures (not necessarily the lowest-energy ones) were further optimized via DFT for a final ranking of their stabilities. For each defect cluster type, we calculated the energy of the MLIP-predicted GS relative to the true GS predicted by DFT, and our results are shown in parentheses in Supplementary Table 3. A value of 0 indicates that the two GSs are identical. Overall, our MLIP successfully identified the true GSs for 26 out of a total of 28 vacancy clusters, and for 18 out of a total of 28 interstitial clusters as confirmed by DFT. For 7 out of the remaining 10 interstitial clusters where MLIP and DFT predict different GSs, the MLIP-predicted GSs are low-energy metastable structures that are only slightly higher in energy than the DFT-predicted GSs by 0.011, 0.014, 0.054, 0.057, 0.068, 0.075, and 0.082 eV, respectively. Similarly, for the remaining two vacancy clusters, the MLIP-predicted GSs are energetically highly competitive metastable structures that lie only 0.008 and 0.014 eV above the DFT-predicted GSs, respectively. The ability of the present MLIP to successfully identify GS and low-energy metastable structures evidences that it can accurately reproduce the DFT PESs of defect clusters in ThO2.

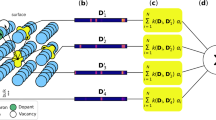

Our first interesting finding is the discovery of many unexpected GS structures that completely defy our physical intuition that constituent point defects within a defect cluster should be positioned in close proximity to form a “compact” GS. While this guiding heuristic remains valid for vacancy clusters in ThO2, it is inadequate for describing small interstitial clusters. As depicted in Fig. 1a, these compact configurations based on physical intuition are remarkably energetically unfavorable compared to the true GSs, which exhibit decidedly non-compact structures. For example, in the GS structure for 2Thi + 1Oi, the Oi defect prefers to be close to only one of the two Thi defects, rather than both. Furthermore, in the GS structure for the 2Thi + 2Oi cluster, the two Oi defects stay far away from each other to form a zigzag structure. The previously presumed compact structure from our earlier study8, in which the four point defects within the 2Thi + 2Oi cluster form a highly symmetrical tetrahedron, turns out to be a high-energy configuration. Note that the energy differences between these compact configurations and the true GSs, as calculated via both DFT and MLIP, also show good quantitative agreement (see Fig. 1a), further corroborating the accuracy of the MLIP developed in this study.

a shows the unexpected true GSs of small interstitial clusters as compared to the GSs based on physical intuition, while (b) demonstrates the existence of defect polymorphs. The GS structures for 4Thi + nOi and 4VaTh + nVaO clusters are shown in (c) and (d), respectively. Th and O atoms are represented by green and red spheres, respectively. Th interstitials/vacancies and O interstitials/vacancies are shown as yellow and blue spheres, respectively.

Our second intriguing finding is the existence of two distinct stable structures with an energy difference significantly lower than the thermal energy at room temperature (~25 meV). This phenomenon has been observed for certain types of defect clusters in ThO2 (see Fig. 1b) and is termed “defect polymorphism” in our study. Importantly, this discovery introduces a new layer of complexity to our understanding of irradiation effects on material properties. In irradiated samples, these defect polymorphs can coexist due to their energetic degeneracy. However, their impacts on material properties may differ. For example, defect polymorphs with distinct structures can exhibit varying phonon-defect scattering cross-sections22, resulting in different impact on thermal conductivity.

Our third notable discovery is the transformation from 2D to 3D GS structures as a 4Thi + nOi cluster grows in size by absorbing additional oxygen interstitials. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the GS configurations of 4Thi + nOi clusters with n ≤ 8 feature a 2D diamond-shaped arrangement of four Th interstitials, aligned parallel to the {111} plane of ThO2. For the 4Thi + 8Oi cluster, our search also reveals a metastable 2D loop configuration that lies only 0.168 eV above the GS. The strain field created by the extra atomic planes in the Frank loop leads to significant distortion of the ThO2 lattice, as evidenced by the large displacements of nearby Th and O atoms away from their equilibrium positions, to the extent that the original O interstitials in the loop and O atoms belonging to the lattice are no longer distinguishable (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, when the number of O interstitials in the cluster exceeds eight, it becomes energetically more favorable for the four Th interstitials to form a 3D tetrahedron. A similar transition from 2D to 3D has also been observed for 4VaTh + nVaO vacancy clusters as the number of oxygen vacancies increases. In the GS structures of 4VaTh + nVaO clusters with n ≤ 6, the four Th vacancies adopt a diamond-shaped planar configuration. Once n exceeds six, the four Th vacancies assume a tetrahedron arrangement in the GS structures, as depicted in Fig. 1d. Our discovery of vacancy clusters in ThO2 that adopt 2D GS structures is unusual, as conventional wisdom suggests that vacancy clusters prefer 3D configurations such as voids in bcc metals23 and stacking fault tetrahedra in fcc metals24. It is also interesting to note that 2D vacancy platelets were recently observed in He-irradiated hcp Zr25, which will transform into dislocation loops after surpassing a critical size.

Thermodynamic stability of defect clusters against dissociation

To gain insight into the thermodynamic stability of defect clusters in ThO2 against dissociation, we calculated their total and incremental binding energies. The total binding energy represents the energy needed to fully dissociate a defect cluster into isolated point defects, whereas the incremental binding energy is the change in energy when a defect cluster transforms into a smaller-sized cluster by emitting a single point defect. To ensure the thermodynamic stability of a defect cluster against dissociation, its total binding energy and all its incremental binding energies must be positive. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the total binding energies for interstitial and vacancy clusters in ThO2 only become negative for highly charged defect clusters (i.e., interstitial clusters with q > 6 and vacancy clusters with q < -6). For vacancy clusters, the results from both DFT and MLIP are remarkably similar (Fig. 2b). In comparison, larger discrepancies exist between the DFT- and MLIP-calculated total binding energies for interstitial clusters (Fig. 2a). Presumably, compared with vacancy clusters, interstitial clusters have much more complicated PESs, which are more difficult for a neural network to grasp. Figure 2c through 2f further report the incremental binding energies of interstitial and vacancy clusters, as calculated by both DFT and MLIP. We considered the emission of Oi and Thi from interstitial clusters, as well as the emission of VaO and VaTh from vacancy clusters. Except for defect clusters with large charge imbalances, quantitative agreement between DFT and MLIP is observed. Importantly, both DFT and MLIP corroborate the thermodynamic instability of interstitial and vacancy clusters with an absolute charge value | q | > 6, an assumption made in our previous KMC simulations of radiation damage evolution in ThO28. Note that vacancy clusters with q > 6 and q < -6 will reduce their energies by rejecting VaO and VaTh, respectively. Correspondingly, interstitial clusters with q > 6 and q < -6 are thermodynamically unstable against the emission of a single Thi and Oi defect, respectively.

a, b The total binding energies of interstitial and vacancy clusters in their GS configurations, plotted as a function of their charges. The DFT-calculated incremental binding energies are shown in (c) and (d), while (e) and (f) present the corresponding results predicted by MLIP. The shaded areas indicate the range of q values where the defect clusters remain thermodynamically stable against dissociation by exhibiting all positive incremental binding energies.

Discussion

Finding the energetically most stable defect structures in crystalline materials poses a computational hurdle for DFT due to the multitude of metastable states on their PESs. This challenge is compounded by irradiation that leads to prolific formation of defect clusters in materials, whose PESs are considerably more complex than those of individual point defects. In this work, we used ThO2 as a model system to demonstrate that this challenge can be overcome by using MLIP as a cost-effective yet highly accurate surrogate model for DFT during the thorough exploration of defect PESs. Our machine learning-accelerated GS searches revealed several unexpected findings, including defect polymorphism and physically counterintuitive non-compact GS configurations for interstitial clusters. In addition to providing remarkable insights into the nature of TEM-invisible defect clusters in irradiated ThO2 that will significantly degrade its phonon-mediated thermal transport efficiency2, this study showcases the pivotal role of machine learning in addressing fundamental questions about the impact of radiation on material properties. It is important to note that one limitation in our GS search is the confining of individual defects within interstitial clusters to occupy octahedral positions. In future studies, such a constraint can be removed by integrating MLIP with global optimization techniques (e.g., basin hopping8,13 and evolutionary algorithm12,16). Applying the combined DFT and MLIP approach to predict the structures and energetics of irradiation-induced defect clusters in other fluorite-structured oxides such as UO226,27 will also be of great interest.

Before closing, it is worthwhile to shed some light on the underlying physics that govern the stability of defect clusters in ThO2. To facilitate a quantitative analysis, we introduced a local cluster expansion (LCE) model to characterize the configuration dependence of total binding energies for vacancy clusters in ThO2. Using the 2VaTh + 4VaO cluster as an exemplar, we demonstrated that the MLIP-predicted total binding energies for its 151 symmetrically distinct configurations can be accurately reproduced by a LCE with a RMSD of 0.1 eV (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). Our LCE model employs only 12 figures, including three VaTh-VaO pairs, seven VaO-VaO pairs, and two VaTh-VaO-VaO triplets. The parameterized interaction energies of the LCE decidedly show that the dominant contributions to the stability of a vacancy cluster are due to attractive interactions (Jf < 0) between first-nearest-neighbor (1nn) VaTh-VaO pairs, which are considerably stronger than interactions between second-nearest-neighbor and third-nearest-neighbor VaTh-VaO pairs. Importantly, this insight rationalizes why our physical intuition to construct compact vacancy clusters, thereby maximizing the number of 1nn VaTh-VaO pairs, leads to the identification of their true GS configurations. Our LCE further reveals that interactions between VaO-VaO pairs are consistently repulsive (Jf > 0), with magnitudes diminishing as the distance between VaO increases. These characteristics are typical of electrostatic attraction and repulsion between point defects with charges of opposite and same signs, respectively, which likely govern the stability of vacancy clusters in ThO2.

a Direct comparisons between MLIP calculated and LCE predicted total binding energies of all 151 configurations of the 2VaTh + 4VaO cluster. The solid line represents perfect agreement between the two methods. b The interaction energies of pair and triplet figures plotted as a function of their sizes. The GS and low-energy metastable configurations of 2VaTh + 4VaO are shown as insets in (a), where Th atoms, O atoms, Th vacancies, and O vacancies are represented by green, red, yellow, and blue spheres, respectively.

For the 2VaTh + 4VaO cluster, we identified a low-energy metastable structure (Fig. 3a) that lies only 0.035, 0.039, and 0.041 eV above the GS as determined by DFT, MLIP, and LCE, respectively. Notably, the small energy difference between the low-energy metastable configuration and the GS stems from a repulsive seventh-nearest-neighbor (7nn) VaO-VaO pair, which is present in the metastable configuration but absent in the GS (see Supplementary Table 4). We therefore propose long-range electrostatic interactions between charged point defects as a plausible explanation for the observed defect polymorphism. Importantly, since the 7nn separation between two VaO defects (7.8 Å) falls within the cutoff radius (10 Å) of our MLIP, it is capable of capturing this subtle interaction.

Guided by our physical intuition, we searched for the GSs of interstitial clusters by constructing compact configurations that maximize the number of 1nn Thi-Oi pairs, which are electrostatically attractive due to the oppositely signed charges of Thi and Oi. However, this heuristic proved ineffective. For example, compact configurations for 2Thi + 1Oi, 2Thi + 2Oi, 2Thi + 3Oi, and 2Thi + 4Oi clusters (see Fig. 1a) exhibit 2, 4, 6, and 8 1nn Thi-Oi pairs, respectively. In contrast, non-compact GS configurations for these clusters exhibit only 1, 2, 3, and 5 1nn Thi-Oi pairs, respectively. For the 2Thi + 2Oi cluster, we have further considered a diamond-shaped configuration, which is the “perfect” structure from an electrostatic energy perspective. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, it eliminates the electrostatically repulsive 1nn Oi-Oi pair present in the compact configuration, while still maintaining the maximum possible number of 1nn Thi-Oi pairs. Unexpectedly, this diamond configuration proved energetically very unfavorable, which is 1.31 and 1.22 eV higher in energy than the GS zigzag structure according to DFT and MLIP, respectively. These counterintuitive results highlight the inadequacy of relying solely on electrostatic energy to determine the stability of interstitial clusters. Presumably, their GS structures are determined by an intricate interplay between electrostatic and elastic interactions. While non-compact GS configurations are not ideal for promoting electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged Thi and Oi defects, they can sufficiently reduce elastic interaction energies among interstitial defects to offset the increase in electrostatic energy.

Finally, it is noteworthy that developing on-lattice LCE models for interstitial clusters poses significant challenges. The one-to-one correspondence between interstitial defects and pre-defined lattice positions may be lost after strong atomic relaxations, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6. Furthermore, the relaxation process itself can lead to the spontaneous generation of new defects. For example, the GS structure for the 2Thi + 4Oi cluster, as depicted in Fig. 1a, includes a tetrahedron formed by four Oi defects. Remarkably, only three of them are initially part of the 2Thi + 4Oi cluster. The fourth one is formed when a normal O atom is displaced into a nearby octahedral position, simultaneously creating a pair of Oi and VaO defects. Due to these intricacies, determining GS structures of interstitial clusters is a challenging off-lattice problem that can be effectively addressed by a synergy of DFT and MLIP, as demonstrated in this study.

Methods

DFT calculations

We performed DFT calculations within the local density approximation (LDA) of Ceperley-Alder28, as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)29. The projector-augmented wave (PAW) method30 was employed to describe the electron-ion interactions. Large 768-atom 4 × 4 × 4 cubic supercells were employed to minimize artificial defect-defect self-interactions across periodic boundaries. A large plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV and a 1 × 1× 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh for Brillouin zone sampling were found to give fully converged results. All structures were fully relaxed with respect to cell-internal atomic positions with the unit cell volume and shape held fixed, until the Hellmann-Feynman forces dropped below 0.02 eV Å−1.

In our DFT calculations, we assigned nominal charge states of -2, +4, +2, and -4 for Oi, Thi, VaO, and VaTh, respectively. The total charge of a mVaTh + nVaO vacancy cluster composed of m VaTh and n VaO defects can be calculated as q = 2n − 4m. Similarly, the total charge of a mThi + nOi interstitial cluster consisting of m Thi and n Oi defects can be calculated as q = 4m − 2n. We simulated charged defects by artificially adding or subtracting electrons from a defect-containing supercell, with a neutralizing jellium background automatically applied in VASP. Monopole corrections to the total energy were applied as per Leslie and Gillan31:

where q is the net charge of the system, α = 2.8373 is the Madelung constant of a point charge placed in a homogeneous neutralizing background, L is the dimension of the cubic supercell, and ε = 18.9 is the dielectric constant of ThO2.

Total and incremental binding energies

The total binding energies of vacancy and interstitial clusters were calculated as follows:

where E(ThNO2N) is the total energy of the perfect supercell containing N formula units of ThO2. E(ThNO2N−1), E(ThNO2N+1), E(ThN−1O2N), E(ThN+1O2N), E(ThN−mO2N−n), and E(ThN+mO2N+n) represent the total energies of ThO2 supercells containing VaO, Oi, VaTh, Thi, mVaTh + nVaO, and mThi + nOi defects, respectively. These energies can be computed using either DFT or MLIP. A positive total binding energy indicates attraction between individual point defects, whereas a negative value indicates repulsion.

The incremental binding energies for the emission of Oi and Thi from a mThi + nOi cluster can be calculated from the differences in total binding energies as:

Similarly, the incremental binding energies for the emission of VaO and VaTh from a mVaTh + nVaO cluster can be calculated as:

By these definitions, it is energetically favorable for defect clusters that exhibit negative incremental binding energies to emit point defects and shrink in size.

A local cluster expansion model for vacancy clusters in ThO2

In this study, motivated by the success of the cluster expansion technique (see ref. 32 and references therein) in solving alloy problems, we propose to calculate the total binding energy of a vacancy cluster with configuration σ using the following equation:

where f represents a figure composed of a group of k point defects within a vacancy cluster (k = 1, 2, 3 indicates single site, pair, and triplet, etc.). Nf(σ) is the count of f-type figures in a vacancy cluster with configuration σ. Jf is the configuration-independent interaction energy that measures the contribution of a figure of type f to the total binding energy of a vacancy cluster. Once the set of interaction energies {Jf} is known, one can efficiently predict the total binding energy of any configuration for a vacancy cluster without the necessity for additional MLIP or DFT calculations. Since the total binding energies are calculated using isolated point defects as reference states, our cluster expansion naturally excludes terms corresponding to empty and single-site figures. Furthermore, our cluster expansion is local in nature since it explicitly considers only the geometric arrangements of point defects in a vacancy cluster, disregarding all lattice Th and O atoms in the surrounding matrix. The effects of these lattice atoms are however implicitly included in the calculations of total binding energies used to parameterize the local cluster expansion.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and supplementary materials. The MLIP for ThO2 is available upon request.

References

De la Rubia, T. D. et al. Multiscale modelling of plastic flow localization in irradiated materials. Nature 406, 871–874 (2000).

Hurley, D. H. et al. Thermal energy transport in oxide nuclear fuel. Chem. Rev. 122, 3711–3762 (2022).

Dennett, C. A. et al. An integrated experimental and computational investigation of defect and microstructural effects on thermal transport in thorium dioxide. Acta Mater. 213, 116934 (2021).

Zheng, R. Y., Jian, W. R., Beyerlein, I. J. & Han, W. Z. Atomic-scale hidden point-defect complexes induce ultrahigh-irradiation hardening in tungsten. Nano Lett. 21, 5798–5804 (2021).

Chauhan, V. S. et al. Indirect characterization of point defects in proton irradiated ceria. Materialia 15, 101019 (2021).

Mosquera-Lois, I., Kavanagh, S. R., Walsh, A. & Scanlon, D. O. Identifying the ground state structures of point defects in solids. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 25 (2023).

Fu, C. C., Torre, J. D., Willaime, F., Bocquet, J. L. & Barbu, A. Multiscale modelling of defect kinetics in irradiated iron. Nat. Mater. 4, 68–74 (2005).

Jiang, C. et al. Unraveling small-scale defects in irradiated ThO2 using kinetic Monte Carlo simulations. Scr. Mater. 214, 114684 (2022).

Sun, C. et al. Unveiling the interaction of nanopatterned void superlattices with irradiation cascades. Acta Mater. 239, 118282 (2022).

Jiang, C. et al. Noble gas bubbles in bcc metals: Ab initio-based theory and kinetic Monte Carlo modeling. Acta Mater. 213, 116961 (2021).

Wirth, B. D., Hu, X., Kohnert, A. & Xu, D. Modeling defect cluster evolution in irradiated structural materials: Focus on comparing to high-resolution experimental characterization studies. J. Mater. Res. 30, 1440–1455 (2015).

Arrigoni, M. & Madsen, G. K. H. Evolutionary computing and machine learning for discovering of low-energy defect configurations. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 71 (2021).

Jiang, C., Morgan, D. & Szlufarska, I. Structures and stabilities of small carbon interstitial clusters in cubic silicon carbide. Acta Mater. 62, 162–172 (2014).

Medasani, B. et al. Predicting defect behavior in B2 intermetallics by merging ab initio modeling and machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 1 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Accelerated prediction of atomically precise cluster structures using on-the-fly machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 173 (2022).

Merte, L. R. et al. Structure of an ultrathin oxide on Pt3Sn(111) solved by machine learning enhanced global optimization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204244 (2022).

Deringer, V. L., Caro, M. A. & Csanyi, G. Machine learning interatomic potentials as emerging tools for materials science. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902765 (2019).

Zuo, Y. et al. Performance and cost assessment of machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 731–745 (2020).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Singraber, A., Behler, J. & Dellago, C. Library-based LAMMPS implementation of high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1827–1840 (2019).

Staacke, C. G. et al. On the role of long-range electrostatics in machine-learned interatomic potentials for complex battery materials. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 12562–12569 (2021).

Jin, M., Dennett, C. A., Hurley, D. H. & Khafizov, M. Impact of small defects and dislocation loops on phonon scattering and thermal transport in ThO2. J. Nucl. Mater. 566, 153758 (2022).

Hou, J., You, Y. W., Kong, X. S., Song, J. & Liu, C. S. Accurate prediction of vacancy cluster structures and energetics in bcc transition metals. Acta Mater. 211, 116860 (2021).

Zhao, S., Zhang, Y. & Weber, W. J. Stability of vacancy-type defect clusters in Ni based on first-principles and molecular dynamics simulations. Scr. Mater. 145, 71–75 (2018).

Liu, S. M., Beyerlein, I. J. & Han, W. Z. Two-dimensional vacancy platelets as precursors for basal dislocation loops in hexagonal zirconium. Nat. Commun. 11, 5766 (2020).

Matthews, C. et al. Cluster dynamics simulation of uranium self-diffusion during irradiation in UO2. J. Nucl. Mater. 527, 151787 (2019).

Liu, X. Y. & Andersson, D. A. Small uranium and oxygen interstitial clusters in UO2: An empirical potential study. J. Nucl. Mater. 547, 152783 (2021).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Jouber, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Leslie, M. & Gillan, M. J. The energy and elastic dipole tensor of defects in ionic crystals calculated by the supercell method. J. Phys. C. 18, 973–982 (1985).

Jiang, C. Vacancy ordering in Co3AlCx alloys: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 78, 064206 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Center for Thermal Energy Transport under Irradiation (TETI), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Development of MLIP for ThO2 was supported by the INL Laboratory Directed Research & Development (LDRD) Program under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517. This research made use of the resources of the High Performance Computing Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under Contract No. DE-AC07-05ID14517.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J. and D.H.H. conceived the initial ideas. C.J. performed the DFT calculations, MLIP training, GS searches, data analyses, and LCE fitting. D.H.H. supervised the overall project. C.J., D.H.H., C.A.M., and M.K. discussed the ideas further and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, C., Marianetti, C.A., Khafizov, M. et al. Machine learning potential assisted exploration of complex defect potential energy surfaces. npj Comput Mater 10, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01207-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01207-8