Abstract

The ground and excited state calculations at key geometries, such as the Frank–Condon (FC) and the conical intersection (CI) geometries, are essential for understanding photophysical properties. To compute these geometries on noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices, we proposed a strategy that combined a chemistry-inspired spin-restricted ansatz and a new excited state calculation method called the variational quantum eigensolver under automatically-adjusted constraints (VQE/AC). Unlike the conventional excited state calculation method, called the variational quantum deflation, the VQE/AC does not require the pre-determination of constraint weights and has the potential to describe smooth potential energy surfaces. To validate this strategy, we performed the excited state calculations at the FC and CI geometries of ethylene and phenol blue at the complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) level of theory, and found that the energy errors were at most 2 kcal mol−1 even on the ibm_kawasaki device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computational chemistry has contributed significantly to a better understanding of the mechanisms of chemical phenomena and rational material design. In particular, with the development of the density functional theory (DFT)1,2 and time-dependent (TD) DFT methods3, computational chemistry has become an indispensable technology in a wide range of fields dealing with catalytic, optical, optoelectronic, magnetic, and biomimetic materials. However, the DFT and TDDFT methods are not appropriate for computing quasi-degenerated systems, in which the static electronic correlation makes a large contribution. To take into account electronic correlations, the full-configuration interaction (FCI) method and multireference (MR) calculation methods4 such as the complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF)5, MR configuration interaction5, MR coupled-cluster6, MR perturbation theory7, and MR combined with DFT methods8 have been proposed. However, their applications to large molecules, in which large active spaces are required, are too demanding. For instance, polynuclear metal complexes such as the Fe7MoS9 and Mn3CaO4 complexes in nitrogenase and photosynthetic photosystem II, respectively, have quasi-degenerate characteristics due to the 3d orbitals of the metals, and their computational analyses by MR calculations are still awaited9,10. The MR calculation methods are also indispensable for exploring the potential energy surfaces (PESs) of the excited states, especially near the conical intersection (CI) region, which induces the non-radiative deactivation of optical materials11,12,13.

To solve this problem, quantum chemists have given attention to developing novel methods for performing FCI or MR calculations on quantum computers10,14,15,16,17,18,19. This is because quantum computing can, in principle, reduce the computational time for the FCI in a polynomial compared to the classical devices, which require an exponential computation time20,21,22,23,24. However, because the current quantum devices, the so-called noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, are hamstrung by noisiness and short decoherence times, the focus has been on calculation methods that can run on short quantum circuits25,26,27. In the search for quantum advantage with the NISQ devices, various algorithms, including variational quantum algorithm (VQA)28, full quantum eigensolver with the approximation using the perturbation theory29,30, quantum annealing31,32, gaussian boson sampling33, analog quantum computation34, and digital-analog quantum computation35, have been proposed. Especially, the VQA for calculating the ground state and the excited states are called the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE)36 and variational quantum deflation (VQD)37,38, respectively. These methods have been applied to PESs for small molecules39,40,41, periodic systems42,43,44, energy profiles for lithium batteries45,46, and the excitation energies of organic light-emitting diode (OLED) emitters47.

Over the past few years, attention has also been given to methodologies for applying the CASSCF calculation, in which the molecular orbitals are optimized with respect to the wavefunction obtained by the VQA48,49,50. CASSCF calculations using quantum devices have the advantage of handling larger active spaces than those using classical devices, thereby enhancing the interpretative and predictive power of the CASSCF calculations. Moreover, these methods were recently extended to perform state-average (SA) CASSCF calculations to provide a balanced description of all the states involved in a photo-excitation system51,52. All these pioneering studies, however, have only validated the theoretical accuracy of CASSCF calculations on an ideal quantum computer, which is far from practical enough to be useful for the current NISQ devices.

To obtain sufficient energy accuracy for CASSCF calculations using NISQ devices25, promising error mitigation approaches53,54 have been proposed. However, these techniques still do not provide sufficient accuracy for investigating the PES using the CASSCF method. For example, in the case of the ground state calculations for Li complexes45, a deviation of several mHa (3–5 kcal mol−1) as well as a large spin contamination were observed even with the error mitigation approach. The situation becomes much more pronounced for the excitation energy calculation of OLED emitter molecules47 because of the ‘cost function’ for the excited state calculation (see Descriptions of the VQE and VQD in “Results and discussion”). Thus, further improvements in the computational techniques are needed to achieve an accuracy that is approximately one order of magnitude higher than those of the current approaches.

To deal with this issue, in this work, we propose an excited state calculation method, named VQE under automatically-adjusted constraints (VQE/AC), and combined it with an appropriate ansatz that restricts the spin multiplicity55,56. The VQE/AC is based on a classical constrained optimization algorithm and does not require the cost function, which could cause an error in the VQD calculation. The spin-restricted ansatz can span the subspace of the target spin state, which could avoid the undesired spin contamination. The advantages of this ansatz are as follows: (1) minimum number of variational parameters to fully span the appropriate symmetry subspace and (2) shorter circuit depth than those of other conventional ansätze. To validate our strategy, we perform the CASSCF calculations for ethylene and phenol blue (4-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)imino]-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one, shown in Fig. 1). The phenol blue is a nonfluorescent dye, which shows an ultrafast internal conversion from the excited state to the ground state after photoexcitation, and its optical properties have been investigated by both spectroscopic experiments57,58 and a theoretical simulation59. From the viewpoint of an industrial application, the phenol blue is a primary skeletal structure part of indoanilline dyes, which have been applied to cyan-colored materials in photography and dye diffusion thermal transfer printings. To develop a robust dye, it is very important to locate its CI where the nonradiative decay occurs efficiently. In this paper, we first describe the basic idea of VQE, VQD, VQE/AC, and the spin-restricted ansatz. We then apply our approach to the ground and excited states of ethylene at the Frank–Condon (FC) and CI geometries, and compare it with other methods. We also demonstrate the feasibility of our approach by the excited state calculation of the phenol blue dye using the simulators and the real device called ibm_kawasaki.

Results and discussion

Descriptions of the VQE and VQD

The VQE36 is a ground-state calculation method that uses quantum circuits. The basic idea of the VQE comes from the variational principle: the energy expectation value calculated by any trial wavefunction Ψ(θ) with parameters θ satisfies the following:

where \(\hat H\) is a given Hamiltonian, and E0 is the minimum eigenvalue. Because this equality is valid only when the trial function is the exact eigenstate of the Hamiltonian (i.e., the wavefunction of the ground state), the energy and wavefunction of the ground state can be obtained by finding the parameters θ that minimize the energy expectation value. The trial wavefunction in the VQE is constructed using a quantum circuit called ansatz, and the energy expectation value is computed via quantum measurement. The measurement outcome and parameters are handed over to a classical optimizer, and the parameters are updated so that the energy decreases. The ground state can be obtained by repeating this process until the energy converges.

The excited states can be calculated in a manner similar to the method used by the VQE by minimizing a cost function instead of the energy. This method is called VQD37,38. The definition of the cost function depends on the target state, as well as the target system. For instance, the cost function, C1(θ), for the first excited state can be defined as follows:

where Ψ0 is the ground state wavefunction that was previously obtained by the VQE, and β is a hyperparameter that must be given before the VQD calculation. The second term of Eq. (2) implies the constraint of searching the subspace orthogonal to the ground state. The parameter β needs to be sufficiently large (roughly speaking, greater than the energy difference between the ground state and the excited state)37,60,61. However, too large β could lead to an undesired higher excited state. Another possible cost function, C2(θ), that can be used to calculate the first singlet excited state as follows37:

where γ is a hyperparameter that constrains the search to a singlet. This cost function is useful for calculating organic molecules whose optical functions are mainly determined by the characteristics of the first singlet excited state (S1) and the singlet ground state (S0). With appropriate hyperparameters, the VQD with the cost function C2(θ) could give the S1 state, while that with C1(θ) could give the lowest triplet excited state (T1). When the spin multiplicity of the target state is constrained to be a singlet by the ansatz (as mentioned below), however, the VQD with C1(θ) could also give the S1 state.

VQE under automatically-adjusted constraints (VQE/AC)

Another way to minimize the energy with the constraint of the orthogonality to the ground state is to apply constrained optimization using a linear approximation (COBYLA)62, which is a numerical optimization method that does not require the derivative of the objective function (i.e., the energy). To obtain the first excited state, the energy expectation value is minimized with the constraint of the overlap such as \(\left| {\left\langle {{\Psi}\left( {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}} \right)\left| {{\Psi}_0} \right.} \right\rangle } \right|^2 \le 10^{ - 4}\). In other words, the weight of the constraint, which corresponds to β in VQD, is automatically adjusted within the algorithm of the COBYLA. We named this excited state calculation VQE under automatically-adjusted constraints (VQE/AC). There are two advantages to VQE/AC. First, the cost function tuning is not required, unlike VQD. The second is the applicability to higher excited state calculations because more than two constraints can be considered in the COBYLA. Because the number of constraints does not increase exponentially, the computational cost of a higher excited state calculation should not be too demanding.

Spin-restricted ansatz

The spin multiplicity of the trial wavefunction can be restricted using an ansatz called the spin-restricted ansatz. As an example to illustrate the ansatz that restricts the trial wavefunction to a singlet, consider a wavefunction represented by the electronic configurations obtained by the active space with two electrons in two orbitals (i.e., HOMO and LUMO). Under the constraints of the electron number, N = 2, and the spin z-projection, Sz = 0, the active space can be mapped to the qubit space in the manner of parity mapping63 as follows:

where \(a_{{{\mathrm{X}}}}^{\dagger}\) is the generating operator of an electron in spin orbital X, \(\left| {{{{\mathrm{vac}}}}} \right\rangle\) is the vacuum state, and the up and down arrows represent two spin eigenstates. Here, the singlet and triplet configurations are represented by a linear combination of Eq. (4). The doubly occupied singlet configurations in the HOMO and LUMO correspond to \(\left| {01} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {10} \right\rangle\), respectively. The open-shell singlet and triplet configurations are represented by \(\frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\left| {00} \right\rangle + \left| {11} \right\rangle } \right)\) and \(\frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\left| {00} \right\rangle - \left| {11} \right\rangle } \right)\), respectively. When only the singlet states are focused on, their wavefunctions can be represented by a linear combination of only the singlet configurations. Thus, a quantum circuit that constructs trial functions within the singlet subspace is efficient in avoiding undesired spin contamination. Figure 2 shows a quantum circuit that constructs the singlet subspace. In this circuit, the Pauli X-gate is applied to the second qubit, q1, to prepare the doubly excited configuration, \(\left| {10} \right\rangle\), as the initial state. Then, q0 and q1 are transformed into \(\sin \left( {\theta _0/2} \right)\left| {01} \right\rangle + \cos \left( {\theta _0/2} \right)\left| {10} \right\rangle\) by the Y-rotation gate, \(R_y\left( {\theta _0} \right)\), combined with the CNOT gate. The \(R_y\left( {\theta _1} \right)\) and \(R_y\left( { - \theta _1} \right)\) pair partly transforms \(\left| {01} \right\rangle - \left| {10} \right\rangle\) into \(\left| {00} \right\rangle + \left| {11} \right\rangle\) to finally produce a superposition of the three singlet configurations as follows:

This ansatz is realized by a circuit with minimum gate operations. It should be noted that our spin-restricted ansatz could be expanded for larger active spaces. Gard et al.55 reported ansätze based on the same concept with the Jordan-Wigner mapping64 and showed the general construction scheme of circuits that enforce particle number and spin for any number of active orbitals and electrons. In Supplementary Note 2, we also show the way to construct the spin-restricted ansatz for larger CAS problems (the CAS(4,3) and (4,4) cases as examples) using the parity mapping with two-qubit reduction. Though the number of gates of the spin-restricted ansatz increased as the number of active orbitals increased, the number of parameters to be optimized is still fewer than that of hardware efficient ansätze.

X, Ry, and the ⊕ connected to a dot represent the Pauli X-gate, Y-rotational gate, and CNOT gate, respectively. q0 and q1 are the labels for the two qubits and the order of tensor products shown in Eqs. (4) and (5) is \(\left| {q_1q_0} \right\rangle = \left| {q_1} \right\rangle \otimes \left| {q_0} \right\rangle\).

To obtain deeper insights into the singlet subspace, we plotted the energy landscape against the circuit parameters θ0 and θ1. Figure 3 shows the energy landscape of ethylene calculated using the CASCI method, whose active space includes two electrons in two orbitals. As shown in Eq. (5), the coefficient of each electronic configuration is represented by the trigonometric functions of parameters θ0 and θ1 (in other words, the coefficient changes periodically with respect to θ0 and θ1), which results in the periodic energy landscape. In Fig. 3, one of the minimum points, the first-order saddle point, and the second-order saddle point are shown by the white circle, black x, and black triangle, respectively. S0 corresponds to the minimum energy points, which can be determined by minimizing the energy value. S1 corresponds to the first-order saddle point because it is located at the minimum energy point within the subspace that satisfies the orthogonality to S0 (shown by the white solid line in Fig. 3). Therefore, S1 can easily be found using a conventional optimization method under orthogonality constraints. In the same way, the higher (nth) singlet excited state, which corresponds to the nth-order saddle point, could be obtained by energy minimization within the subspace orthogonal to all the lower singlet states.

The energies of ethylene were computed at the FC structure using the CASCI/STO-3G method, whose active space included two electrons in two orbitals. One of the minimum energy points (S0), the first-order saddle point (S1), and the second-order saddle point (S2) are shown by the white circle, black x, and black triangle, respectively. The white solid line represents the region where the wavefunction is orthogonal to S0.

Comparison of ansätze

Two quantum circuit simulators implemented in Qiskit65 were used for all the CASSCF calculations. One was the statevector simulator, which simulated the ideal quantum state and did not involve any noise or statistical error. The other was a noisy-QASM simulator that used a realistic device (ibmq_belem) noise model. We expect that the appropriate method provides the negligible energy difference between the statevector and noisy-QASM simulators.

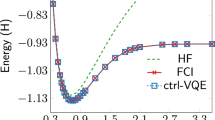

First, to examine the dependency on the ansatz, this study focused on the ground state (S0) energy of ethylene at the FC geometry calculated with the state-specific (SS) CASSCF method using two types of ansätze, called the heuristic and chemistry-inspired ansatzes. Figure 4 shows the S0 energy calculated with three heuristic ansatzes, including the real amplitudes (RA) ansatz66 (with 2 and 6 repetitions (reps) conditions, denoted as RA(2) and RA(6), respectively), the efficient SU2 ansatz67, and a chemistry-inspired ansatz, that is, the spin-restricted ansatz. As shown in Fig. 4, when using the statevector simulator, the energy converged to an exact value for all four ansätze. With the noisy-QASM simulator, the calculated energies were higher than the exact value for all the ansätze, but the errors were within 2.5 kcal mol−1 at most. It should be noted that the error tended to be larger when using a more complex quantum circuit. As shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1, the quantum circuit for the spin-restricted ansatz was shorter than those of the heuristic ansätze. In addition, the number of the parameters for the spin-restricted ansatz was only two, which was smaller than the numbers used for the heuristic ansätze (6, 14, and 8 for RA(2), RA(6), and efficient SU2, respectively). It is known that calculations using complex circuits (using many gates and parameters) suffer from the dreaded ‘Barren Plateau’ of insolvability, where energy minimization becomes difficult due to the flat energy landscape68. Thus, the spin-restricted ansatz might have an advantage over the heuristic ansätze by avoiding this problem.

The energy deviations ΔE (in kcal mol−1) from the exact values were calculated at the FC geometry using SS-CASSCF with statevector (in red) and noisy-QASM simulators (in blue). Detailed values are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Next, we considered the first singlet excited state (S1), as well as the S0 state of ethylene, at the FC and CI geometries. As summarized in Table 1, the calculation methods depend on the ansatz, geometry, and the electronic state. In the case of heuristic ansatz, the calculation methods depend on the geometry. Focusing on the FC geometry, the S0 can be obtained by the VQE, while the S1 can be obtained by the VQD with the cost function C2(θ) in Eq. (3). The hyperparameter β, which constrained the search within the subspace orthogonal to S0, was manually adjusted and set to 1. The parameter γ, which constrained the search within the singlet subspace, needed to be positive and adjusted to 1 because triplet excited states could be more stable than S1. Focusing on the CI geometry, where the S0 and S1 energies were equal, the VQE gave the triplet state (T1) because T1 was always more stable than S1. Therefore, to calculate S0, the VQD with the parameters (β, γ) = (0, 1) had to be used instead of the VQE. In the case of the spin-restricted ansatz, on the other hand, the S0 ground state could be obtained by the VQE for any molecular geometry, and the simpler cost function C1(θ) in Eq. (2) with β = 1 could be used because the spin multiplicity was constrained to a singlet by the ansatz.

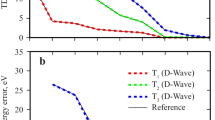

As shown in Fig. 5, when the statevector simulator was used, every calculation at the FC and CI geometries with any ansatz converged to the exact S0 and S1 energies. However, when using the noisy-QASM simulator, the errors in the S0 and S1 energies differed greatly depending on the ansatz and hyperparameter. Focusing on the energies in Fig. 5a–c, the errors calculated with the heuristic ansätze were much larger than those found using the spin-restricted ansatz. To understand the reason for the larger errors with the heuristic ansätze, the expected value of spin squared \(\left\langle {\hat S^2} \right\rangle\) was focused on (see Supplementary Table 2). The deviation of the spin squared value from the exact value (i.e., zero) was relatively large when the heuristic ansätze were used. Thus, undesired spin contamination could be one of the reasons for the energy errors. In other words, the spin-restricted ansatz has a potential advantage to reduce the error on the energy due to the avoiding undesired subspace, which could be applicable for larger active spaces (see Supplementary Note 2). (Note that the errors in the S0 energies calculated by the SA-CASSCF were larger than those calculated by the SS-CASSCF in Fig. 4. It could be understood that inappropriate hyperparameters affected the orbital optimization and eventually both the S0 and S1 energies.) Even though the spin-restricted ansatz was applied, the error in the S1 energy in the CI geometry was as large as 20.96 kcal mol−1 (see Fig. 5d), while the errors in the S1 energy at the FC, as well as the S0 energies, were small (up to 0.35 kcal mol−1). To clarify the large error in the S1 energy, the coefficients of the three singlet electronic configurations were calculated using Eq. (5). As a result, the major component of the excited state at the CI was the doubly excited electronic configuration; in other words, this calculation converged to S2, not S1. This implied that the exploration of the PESs of the excited states using the VQD could be difficult because the parameter β would have to be adjusted for each molecular geometry.

Energy deviations ΔE (in kcal mol−1) from the exact values for S0 at the FC (a), S1 at the FC (b), S0 at the CI (c), and S1 at the CI (d) were calculated using the SA-CASSCF method. The errors in energy obtained by the statevector and noisy-QASM simulators are shown in red and blue, respectively. The results labeled with an ‘*’ indicate that the maximum number of orbital rotations was reached. The parameters were β = 1 for all the ansätze, γ = 1 for the heuristic ansätze. Detailed values are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Comparison of calculation methods for excited states

Next, we examined the performance of VQD with different β and compare them with our proposed excited state calculation method, the VQE/AC. As shown in Fig. 6, we calculated S0 and S1 energies of ethylene with the spin-restricted ansatz and compared these excited state calculation methods. Focusing on the VQD, the S1 energy heavily depended on the parameter β. When the parameter β was set to 1, the excited state at the CI geometry converged to the undesired S2 state, as mentioned above. With the β set to 2.5, both S0 and S1 were calculated successfully. When the β was larger than 5, even the statevector simulator (and of course the noisy-QASM simulator) gave inaccurate energy values, indicating that these β values were not appropriate. Thus, the parameter β needed to be carefully and manually adjusted and was 2.5 for ethylene. Although higher excited states such as S2 were beyond the scope of this study, it can be expected that the cost functions could be more difficult to adjust because they must involve constraints on all the lower excited states. On the other hand, when the VQE/AC was applied, the errors in energies at both the FC and CI obtained with the noisy-QASM simulator were very small (up to 0.45 kcal mol−1). It should be emphasized that VQE/AC does not require the tuning of the cost function, unlike the VQD. Therefore, the VQE/AC could be used to describe smooth PESs even when using the noisy-QASM simulator, i.e., under realistic device noise.

Energy deviations ΔE (in kcal mol−1) from the exact values for S0 at the FC (a), S1 at the FC (b), S0 at the CI (c), and S1 at the CI (d) were calculated using the SA-CASSCF method. The errors in energy obtained by the statevector and noisy-QASM simulators are shown in red and blue, respectively. The results labeled with an ‘*’ indicate that the maximum number of orbital rotations was reached. Detailed values are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

The VQE/AC could be combined with other ansätze as well as the spin-restricted ansatz. For instance, with the RA(2) ansatz, where six parameters needed to be optimized, the VQE/AC consistently gave relatively small energy deviations (< 2.6 kcal mol−1) without any hyperparameter tuning. On the other hand, the VQD parameter β affording the smallest energy deviations depended on the molecular geometry (see Supplementary Table 5). Thus, the VQE/AC could be superior to the VQD for more complicated systems as well. Note that the optimal β parameter was also different for each ansatz (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 5) due to the different energy landscapes along with the θ parameters.

Application to phenol blue

As previously described, the combination of the spin-restricted ansatz and the VQE/AC enabled to give S0 and S1 energies with an error of less than 1 kcal mol−1, even under the realistic device noise model. Next, to verify the applicability of this method to photofunctional molecules, the study focused on a robust dye called phenol blue (see Fig. 7). Focusing on the performance of the VQD method, the most suitable β value for both the FC and CI geometries was 1 (in contrast to the value of 2.5 for ethylene), which indicated that the most appropriate value for this parameter heavily depended on the molecule. The errors in energy calculated by the VQD method with parameter β = 1 were only 0.22 kcal mol−1 at most even when using the noisy-QASM simulator. In the case of the VQE/AC, the errors in the S0 and S1 energies were only 0.14 kcal mol−1 at most. Therefore, it can be stated that the proposed strategy (VQE/AC with spin-restricted ansatz) is efficient in calculating the excited states, as well as the ground states, of large molecules. This method gave a small error at any geometry without any hyperparameter tuning, which indicated that it is applicable to describe PESs of the ground and excited states.

Energy deviations ΔE (in kcal mol−1) from the exact values for S0 at the FC (a), S1 at the FC (b), S0 at the CI (c), and S1 at the CI (d) were calculated using the SA-CASSCF method. The errors in energy obtained by the statevector and noisy-QASM simulators are shown in red and blue, respectively. Detailed values are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Finally, the ground and excited state energies of phenol blue were measured on the ibm_kawasaki device using the VQE/AC. The energies of the FC and CI geometries were measured twice each as shown in Table 2. All the calculations converged relatively smoothly: the numbers of orbital update iterations were less than 10 in all the calculations. Though the deviations from the exact solutions were larger than those estimated with the noisy-QASM simulator, they were at most 2 kcal mol−1 and 0.5 kcal mol−1 for the state energies and excitation energies, respectively. It should be noted that the energy deviations at the CI geometry were as small as 0.5 kcal mol−1, which were surprisingly small and showed the high potential to achieve the exploration of the CI geometries. The deviations at the FC geometry, on the other hand, were larger than those at the CI. This could be attributed to the fact that the Hamiltonian structure (Pauli string) at the FC geometry was more sensitive to the device noise than that at the CI geometry. Though precise geometry optimization may still be difficult with an error of 2 kcal mol−1, it could be improved by developing methodologies of purification and error mitigation as well as hardware.

This study investigated a ground and excited state calculation method that can tolerate NISQ devices. Two methods were combined, a chemistry-inspired spin-restricted ansatz with parity mapping and an excited-state calculation method, called the VQE/AC method. The advantage of the spin-restricted ansatz was that the wavefunction could be constructed within the subspace of the target spin multiplicity, which reduced the undesired spin contamination. The VQE/AC used a constrained optimization called COBYLA, with the constraint that the overlap integral between the target state and the ground state was smaller than a threshold such as 10−4. To validate this strategy, the CASSCF method was used for the singlet ground and excited states of ethylene and phenol blue at the FC and CI geometries. The small errors were obtained in the singlet ground and first excited states (i.e., S0 and S1) on a realistic device noise model (<0.5 kcal mol−1) and the real device ‘ibm_kawasaki’ (<2 kcal mol−1). The present calculation results are superior to the previous ones using quantum circuits (at least 2–3 kcal mol−1)45,47. Unlike the conventional excited state calculation method called VQD, the VQE/AC does not require any parameter tuning for the cost function. Thus, the VQE/AC could have the advantage of higher excited state calculations (though this was beyond the scope of this study) compared to the VQD. Moreover, it should be emphasized that the ground and excited state energies could be computed with the same calculation condition for any molecular geometry because parameter tuning was not required. Therefore, the VQE/AC could be used to explore PESs of the ground and excited states, even under a realistic device noise model. In other words, the VQE/AC has much potential for achieving geometry optimization of critical structures on and between the ground and excited states using real NISQ devices. Though this study mainly focused on the proof-of-concept demonstration on the real device, the future targets include the photochemistry of large systems, such as biomolecules and polynuclear metal complexes, which require the use of large active spaces to represent their electronic states. According to ref. 54, the depth of the circuit for the spin-restricted ansatz increased as the number of electronic configurations involved in the active space increased. In addition, the energy error tended to increase with the depth of the circuit. Therefore, the VQE/AC combined with hardware efficient ansätze could be an appropriate strategy to achieve the computation of large systems, which would be the subject of future analyses.

Methods

Workflow and classical computations

In all the CASSCF calculations69,70, the active space included two electrons in two orbitals such as HOMO and LUMO. When only the ground state was focused on, the state-specific (SS) CASSCF was applied. To compute both the ground and first excited states, the state-averaged (SA) CASSCF was applied, in which the average energy of these two states was minimized. The initial (guess) molecular orbitals for the CASSCF were obtained using the Hartree–Fock (HF) method (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The basis sets used for ethylene and phenol blue were STO-3G71 and 6–31G(d)72, respectively. The molecular geometries of ethylene at the FC and CI were optimized at the same level of theory using the classical CASSCF method (without using the quantum circuit) implemented in the MOLPRO73,74,75 and GRRM76,77 programs. The geometries of phenol blue were obtained from a previous study59.

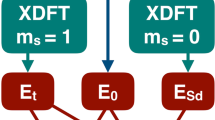

Figure 8 shows the workflow of the CASSCF calculation in this study. As shown in (i) in Fig. 8, we started from calculating the one-body and two-body integrals h1 and h2 (in MO basis) based on the input geometries, spin, and the basis set using the PySCF78 package. Next, the Qiskit package65 was used to prepare the Hamiltonian \(\hat H\) and the spin-squared operator \(\hat S^2\) in the second-quantized form and to map them to qubit operators (see (ii) in Fig. 8). Then, the VQE for S0 (iii) and VQD for S1 (iv) were conducted, in which the expectation values of the energy (or the cost function) and constraints (for VQE/AC) were measured, and the parameters in the ansatz were updated until the energy/cost function converged. The COBYLA62 optimizer in the SciPy79 package was used to update the parameters, and the convergence threshold and the maximum number of iterations were set to 10−4 atomic units and 100, respectively. When iterations reached the maximum, the result at the last step was taken. Each VQE/VQD was followed by state-tomography (ST) and purification (see below). After the calculations for S0 and S1, (v) the one- and two-particle reduced density matrix (1-RDM and 2-RDM) elements for S0 and S1 were measured using the converged parameters. These RDMs were then averaged with weights of (S0, S1) = (1, 0) and (0.5, 0.5) for the SS-CASSCF and SA-CASSCF calculations, respectively. If averaged RDMs and the similarly averaged energy were not converged, the orbitals were updated by modules in the PySCF package and repeated the procedure (ii–v). For the calculations on the simulators, the convergence threshold for the orbitals was set to 10−4 atomic units for the energy, CI gradients, and orbital rotation gradients. They were altered to 10−3 atomic units for the energy, 5 × 10−2 atomic units for the gradients in the calculations on the real device.

Quantum circuits and quantum simulations

The details of the quantum circuit and measurement were as follows. The parity mapping60 was used to map the molecular orbitals to qubits. It exploited the symmetry wherein the total electron number and total alpha electron number should be conserved and allowed the qubits to be reduced by two. Therefore, four spin-orbital calculations were conducted on two qubits. The initial parameters were set to θ = (0, π) for the spin-restricted ansatz (which corresponded to the HF state) and all zero for the other ansatzë. Note that the overlap between two states \(\left| {{\Psi}\left( {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}} \right)} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {{\Psi}_0} \right\rangle\), \(\left| {\left\langle {{\Psi}\left( {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}} \right)\left| {{\Psi}_0} \right.} \right\rangle } \right|^2\), was obtained by measuring the quantum circuit of inverted \(\left| {{\Psi}\left( {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}} \right)} \right\rangle\) combined with \(\left| {{\Psi}_0} \right\rangle\). To measure the expectation values, we used the ‘ibm_kawasaki’ device and two simulators in the Qiskit65 package: the statevector simulator, which simulated an ideal quantum state without any noise or readout error, and noisy-QASM simulator, which employed the realistic noise model from ‘ibmq_belem’ device. For the noisy-QASM simulator and the ibm_kawasaki device, the expectation value was obtained using 8192 shots. The measurement error mitigation implemented in Qiskit was applied for the measurements on the noisy-QASM simulator, otherwise not applied for those on the ibm_kawasaki device because the update of the calibration matrix affected the result. The quantum state-tomography and purification after each VQE/VQD calculation was executed by the following procedure, as found in a previous study47.

1. Measure density matrix ρ.

2. Diagonalize ρ to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors with the classical algorithm in SciPy.

3. Assume that the eigenvector \(\left| \psi \right\rangle\) corresponding to the maximum eigenvalue is the exact state, and re-evaluate the energy as \(\left\langle {\psi \left| {\hat H} \right|\psi } \right\rangle\).

4. Update parameter set θ by minimizing \(\left| {\left\langle {\psi \left| {{\Psi}\left( {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}} \right)} \right.} \right\rangle } \right|^2 - 1\).

Data availability

The electronic energy deviations from the exact values, the Cartesian coordinates, the quantum circuits, and the way to construct the spin-restricted ansatz are shown in the Supplementary Information. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes supporting the present work are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Mardirossian, N. & Head-Gordon, M. Thirty years of density functional theory in computational chemistry: an overview and extensive assessment of 200 density functionals. Mol. Phys. 115, 2315–2372 (2017).

Cohen, A. J., Mori-Sánchez, P. & Yang, W. Challenges for density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 112, 289–320 (2012).

Maitra, N. T. Perspective: fundamental aspects of time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 220901 (2016).

Park, J. W., Al-Saadon, R., MacLeod, M. K., Shiozaki, T. & Vlaisavljevich, B. Multireference electron correlation methods: journeys along potential energy surfaces. Chem. Rev. 120, 5878–5909 (2020).

Szalay, P. G., Muller, T., Gidofalvi, G., Lischka, H. & Shepard, R. Multiconfiguration self-consistent field and multireference configuration interaction methods and applications. Chem. Rev. 112, 108–181 (2012).

Lyakh, D. I., Musial, M., Lotrich, V. F. & Bartlett, R. J. Multireference nature of chemistry: the coupled-cluster view. Chem. Rev. 112, 182–243 (2012).

Angeli, C., Pastore, M. & Cimiraglia, R. New perspectives in multireference perturbation theory: the n-electron valence state approach. Theor. Chem. Acc. 117, 743–754 (2007).

Ghosh, S., Verma, P., Cramer, C. J., Gagliardi, L. & Truhlar, D. G. Combining wave function methods with density functional theory for excited states. Chem. Rev. 118, 7249–7292 (2018).

Vogiatzis, K. D. et al. Computational approach to molecular catalysis by 3d transition metals: challenges and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 119, 2453–2523 (2019).

Reiher, M., Wiebe, N., Svore, K. M., Wecker, D. & Troyer, M. Elucidating reaction mechanisms on quantum computers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7555–7560 (2017).

Matsika, S. Electronic structure methods for the description of nonadiabatic effects and conical intersections. Chem. Rev. 121, 9407–9449 (2021).

Nelson, T. R. et al. Non-adiabatic excited-state molecular dynamics: theory and applications for modeling photophysics in extended molecular materials. Chem. Rev. 120, 2215–2287 (2020).

Lischka, H. et al. Multireference approaches for excited states of molecules. Chem. Rev. 118, 7293–7361 (2018).

Motta, M. & Rice, J. Emerging quantum computing algorithms for quantum chemistry. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1580 (2021).

Shikano, Y., Watanabe, H. C., Nakanishi, K. M. & Ohnishi, Y.-Y. Post-Hartree–Fock method in quantum chemistry for quantum computer. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 230, 1037–1051 (2021).

Bauer, B., Bravyi, S., Motta, M. & Kin-Lic Chan, G. Quantum algorithms for quantum chemistry and quantum materials science. Chem. Rev. 120, 12685–12717 (2020).

McArdle, S., Endo, S., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Benjamin, S. C. & Yuan, X. Quantum computational chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015003 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Quantum chemistry in the age of quantum computing. Chem. Rev. 119, 10856–10915 (2019).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Towards quantum chemistry on a quantum computer. Nat. Chem. 2, 106–111 (2010).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Zalka, C. Simulating quantum systems on a quantum computer. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454, 313–322 (1998).

Kassal, I., Jordan, S. P., Love, P. J., Mohseni, M. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Polynomial-time quantum algorithm for the simulation of chemical dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18681–18686 (2008).

Aspuru-Guzik, A., Dutoi, A. D., Love, P. J. & Head-Gordon, M. Simulated quantum computation of molecular energies. Science 309, 1704–1707 (2005).

Sugisaki, K. et al. Quantum chemistry on quantum computers: a polynomial-time quantum algorithm for constructing the wave functions of open-shell molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 120, 6459–6466 (2016).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Bharti, K. et al. Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 015004 (2022).

Callison, A. & Chancellor, N. Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum era and beyond. Phys. Rev. A 106, 010101 (2022).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 625–644 (2021).

Wei, S., Li, H. & Long, G. A full quantum eigensolver for quantum chemistry simulations. Research 2020, 1486935 (2020).

Gui-Lu, L. General quantum interference principle and duality computer. Commun. Theor. Phys. 45, 825–844 (2006).

Finnila, A. B., Gomez, M. A., Sebenik, C., Stenson, C. & Doll, J. D. Quantum annealing: a new method for minimizing multidimensional functions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 219, 343–348 (1994).

Kadowaki, T. & Nishimori, H. Quantum annealing in the transverse Ising model. Phys. Rev. E 58, 5355–5363 (1998).

Hamilton, C. S. et al. Gaussian Boson sampling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 170501 (2017).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Lamata, L., Parra-Rodriguez, A., Sanz, M. & Solano, E. Digital-analog quantum simulations with superconducting circuits. Adv. Phys. X 3, 1457981 (2018).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 5, 7 (2014).

Higgott, O., Wang, D. C. & Brierley, S. Variational quantum computation of excited states. Quantum 3, 11 (2019).

Wen, J., Lv, D., Yung, M.-H. & Long, G.-L. Variational quantum packaged deflation for arbitrary excited states. Quantum Eng. 3, e80 (2021).

Kandala, A. et al. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 549, 242–246 (2017).

Ollitrault, P. J. et al. Quantum equation of motion for computing molecular excitation energies on a noisy quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043140 (2020).

Verma, P. et al. Scaling up electronic structure calculations on quantum computers: the frozen natural orbital based method of increments. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 034110 (2021).

Yoshioka, N., Nakagawa, Y. O., Ohnishi, Y. & Mizukami, W. Variational quantum simulation for periodic materials. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013052 (2022).

Yamamoto, K., Manrique, D. Z., Khan, I., Sawada, H. & Ramo, D. M. Quantum hardware calculations of periodic systems with partition measurement symmetry verification: Simplified models of hydrogen chain and iron crystals. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033110 (2022).

Kanno, S. & Tada, T. Many-body calculations for periodic materials via restricted Boltzmann machine-based VQE. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 025015 (2021).

Gao, Q. et al. Computational investigations of the lithium superoxide dimer rearrangement on noisy quantum devices. J. Phys. Chem. A 125, 1827–1836 (2021).

Rice, J. E. et al. Quantum computation of dominant products in lithium-sulfur batteries. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 134115 (2021).

Gao, Q. et al. Applications of quantum computing for investigations of electronic transitions in phenylsulfonyl-carbazole TADF emitters. Npj Comput. Mat. 7, 70 (2021).

Takeshita, T. et al. Increasing the representation accuracy of quantum simulations of chemistry without extra quantum resources. Phys. Rev. X 10, 011004 (2020).

Mizukami, W. et al. Orbital optimized unitary coupled cluster theory for quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033421 (2020).

Sokolov, I. O. et al. Quantum orbital-optimized unitary coupled cluster methods in the strongly correlated regime: can quantum algorithms outperform their classical equivalents? J. Chem. Phys. 152, 124107 (2020).

Yalouz, S. et al. A state-averaged orbital-optimized hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for a democratic description of ground and excited states. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 024004 (2021).

Omiya, K. et al. Analytic energy gradient for state-averaged orbital-optimized variational quantum eigensolvers and its application to a photochemical reaction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 741–748 (2022).

Kandala, A. et al. Error mitigation extends the computational reach of a noisy quantum processor. Nature 567, 491 (2019).

McCaskey, A. J. et al. Quantum chemistry as a benchmark for near-term quantum computers. Npj Quantum Inform. 5, 99 (2019).

Gard, B. T. et al. Efficient symmetry-preserving state preparation circuits for the variational quantum eigensolver algorithm. Npj Quantum Inform. 6, 10 (2020).

Barron, G. S. et al. Preserving symmetries for variational quantum eigensolvers in the presence of noise. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 034003 (2021).

Kimura, Y., Yamaguchi, T. & Hirota, N. Photo-excitation dynamics of phenol blue. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2, 1415–1420 (2000).

Ota, C. et al. Ultrafast dynamics of a solvatochromic dye, phenol blue: tautomerization and coherent wavepacket oscillations. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 10832–10842 (2021).

Kobayashi, T., Shiga, M., Murakami, A. & Nakamura, S. Ab initio study of ultrafast photochemical reaction dynamics of phenol blue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6405–6424 (2007).

Kuroiwa, K. & Nakagawa, Y. O. Penalty methods for a variational quantum eigensolver. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013197 (2021).

Shirai, S., Horiba, T. & Hirai, H. Calculation of core-excited and core-ionized states using variational quantum deflation method and applications to photocatalyst modeling. Acs Omega 7, 10840–10853 (2022).

Powell, M. J. D. A direct search optimization method that models the objective and constraint functions by linear interpolation. 6th Workshop Optim. Numer. Anal. 275, 51–67 (1992).

Seeley, J. T., Richard, M. J. & Love, P. J. The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation for quantum computation of electronic structure. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 224109 (2012).

Jordan, P. & Wigner, E. Über das Paulische Äquivalenzverbot. Zeit Phys. 47, 631–651 (1928).

Aleksandrowicz, G. et al. Qiskit: Open-source Framework for Quantum Computing. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2562111 (2021).

Team, Q. D. RalAmplitudes — Qiskit 0.31.0 documentation. https://qiskit.org/documentation/stubs/qiskit.circuit.library.RealAmplitudes.html (2021).

Team, Q. D. EfficientSU2 — Qiskit 0.31.0 documentation. https://qiskit.org/documentation/stubs/qiskit.circuit.library.EfficientSU2.html (2021).

McClean, J. R., Boixo, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N., Babbush, R. & Neven, H. Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4812 (2018).

Werner, H. J. & Knowles, P. J. A second order multiconfiguration SCF procedure with optimum convergence. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 5053–5063 (1985).

Knowles, P. J. & Werner, H. J. An efficient second-order MCSCF method for long configuration expansions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 115, 259–267 (1985).

Hehre, W. J., Stewart, R. F. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. I. Use of Gaussian expansions of Slater-type atomic orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 51, 2657–2664 (1969).

Harihara, P. C. & Pople, J. A. Influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 28, 213–222 (1973).

Werner, H. J., Knowles, P. J., Knizia, G., Manby, F. R. & Schutz, M. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. -Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 242–253 (2012).

Werner, H.-J. et al. MOLPRO. version 2015.1 a package of ab initio programs, https://www.molpro.net (2015).

Werner, H. J. et al. The Molpro quantum chemistry package. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 144107 (2020).

Maeda, S. et al. GRRM17. http://iqce.jp/GRRM/index_e.shtml (2017).

Maeda, S., Ohno, K. & Morokuma, K. Systematic exploration of the mechanism of chemical reactions: the global reaction route mapping (GRRM) strategy using the ADDF and AFIR methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3683–3701 (2013).

Sun, Q. M. et al. PYSCF: the Python-based simulations of chemistry framework. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. -Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, 15 (2018).

Virtanen, P. E. A. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant no. JP17H06445, 20K05438, and JST Gannt no. JPMJPF2221. We also acknowledge the computer resources provided by the Academic Center for Computing and Media Studies (ACCMS) at Kyoto University and by the Research Center of Computer Science (RCCS) at the Institute for Molecular Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G., H.N., S.K., Q.G., T.K., T.I., and M.H. conceived the idea of this work. S.G. developed the VQE/AC and performed calculations on the classical and quantum computers. S.G., H.N., and S.K. developed the spin-restricted ansatz code. All authors contributed to the discussions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gocho, S., Nakamura, H., Kanno, S. et al. Excited state calculations using variational quantum eigensolver with spin-restricted ansätze and automatically-adjusted constraints. npj Comput Mater 9, 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-00965-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-00965-1

This article is cited by

-

Mixed quantum-classical dynamics for near term quantum computers

Communications Physics (2023)