Abstract

A magnetic bimeron is an in-plane topological counterpart of a magnetic skyrmion. Despite the topological equivalence, their statics and dynamics could be distinct, making them attractive from the perspectives of both physics and spintronic applications. In this work, we demonstrate the stabilization of bimeron solitons and clusters in the antiferromagnetic (AFM) thin film with interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI). Bimerons demonstrate high current-driven mobility as generic AFM solitons, while featuring anisotropic and relativistic dynamics excited by currents with in-plane and out-of-plane polarizations, respectively. Moreover, these spin textures can absorb other bimeron solitons or clusters along the translational direction to acquire a wide range of Néel topological numbers. The clustering involves the rearrangement of topological structures, and gives rise to remarkable changes in static and dynamical properties. The merits of AFM bimeron clusters reveal a potential path to unify multibit data creation, transmission, storage, and even topology-based computation within the same material system, and may stimulate spintronic devices enabling innovative paradigms of data manipulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The last decade witnessed a rapid increase in our understanding about magnetic skyrmions1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These spin textures are topologically-protected, and can be effectively manipulated by spin currents8,9 or electric field10,11, thus may serve as an ideal information carriers. In recent years, the in-plane analog of a magnetic skyrmion, named a magnetic bimeron, is gaining a lot of attention12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. The topologically nontrivial square meron lattice has been experimentally observed in the chiral magnet Co8Zn9Mn314. More recently, isolated meron–antimeron pairs and bimerons have been stabilized in Py film by magnetic imprinting15. Despite the topological equivalence between the skyrmion and the bimeron soliton, their magnetic static and dynamical properties are distinct, making the magnetic bimeron attractive from the perspectives of both fundamental physics and practical applications in spintronic materials with in-plane anisotropy.

On the other hand, intensive efforts have been devoted to exploit the topological spin textures in other magnetic systems, such as two-dimensional (2D) materials24, frustrated materials18,25, liquid crystals26,27, and antiferromagnets28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Among them, the antiferromagnetic materials show great potential to bring topological spin textures closer to the real applications. In AFM systems, the magnetic moments of the coupled sublattices cancel out, which leads to nearly zero dipolar field and enhances the stability of nanoscale topological structures. The topological charges in the sublattice space also cancel out, and thus making the spin textures free from the skyrmion Hall effect37,38,39. Moreover, the canting of the magnetic momentum leads to extra torques facilitating ultrafast dynamics of AFM system. As a result, the mobility of AFM topological spin structures is much higher than their ferromagnetic (FM) counterparts31,32,33. Consequently, the manipulation of AFM topological structures has lower power consumption, which is highly attractive from the point of view of practical applications.

In this work, we demonstrate the stabilization of asymmetric bimeron solitons and clusters in AFM thin films with interfacial DMI40. We combine analytical and numerical approaches, and systematically investigate their statics and current-driven dynamics. Our main result lies in two aspects: (1) AFM bimerons can be effectively manipulated by spin current, and their dynamics, such as velocity and deformation, have a strong dependence on the direction of the current polarization. (2) AFM bimeron solitons exhibit translational attractive interaction, which enables the formation of clusters with a wide range of Néel topological numbers. Moreover, their counterparts with opposite Néel topological charge exist. The above characteristics envision a rich class of particle-like spin textures allowed by the in-plane AFM system, which can be manipulated by currents with high flexibility and efficiency. On these merits, AFM bimeron clusters may open the avenue for spintronic devices enabling innovative paradigm of data manipulations.

Results and discussion

Theoretical model

We consider the G-type cubic antiferromagnetic thin film with in-plane uniaxial anisotropy, for which the interfacial DMI can be introduced by an adjacent heavy metal layer. The total Hamiltonian of the AFM system can be written as

where Sk and Sl (\(\left|{\bf{S}}\right|\) = 1) are the spin vectors, J (<0 for antiferromagnets), Ka and Dkl are the AFM exchange constant, the magnetic anisotropy constant and the DMI vector, respectively, and we take \(\left|{{\bf{D}}}_{{\rm{kl}}}\right|={D}_{{\rm{I}}}\). ne = eX is the direction of the in-plane magnetic easy axis. By linearly combining Sk and Sl, the net magnetization m = (Sl + Sk)/2 and the staggered magnetization (or Néel vector) n = (Sl − Sk)/2 of the sublattice pair are defined. Considering the nearest neighboring spins, the AFM energy in the continuum form can be written as41:

where λ = −8J/aΔ2, A = −J/a, and L = −4J/aΔ are the homogeneous exchange constant, inhomogeneous exchange constant and parity-breaking constant, respectively. Here a is the lattice constant, and \(\Delta =\sqrt{2}a\). wD = D [nz(∇ ⋅ n) − (n ⋅ ∇)nz] is the DMI energy density, with D being the DMI constant40. We note that the signs of the anisotropic terms ∂xn ⋅ ∂yn, m ⋅ ∂xn, and m ⋅ ∂yn are sensitive to the definition of the sublattice pair, and will not affect the cubic symmetry of the AFM system. The detailed derivation of Eq. (2) and the symmetry analysis are given in Supplementary Note 1. We use MuMax3 for the later simulations (see “Methods” section), and adopt the following continuum-scale parameters with Aex = −A/2 = − 1.6475 pJ m−1, D = 0.36 mJ m−2, K = 5.8 × 104 J m−3, saturation magnetization Ms = 3.76 × 105 A m−1, damping constant α = 0.01. Taking the lattice constant a = 0.5 nm, the atomic-scale parameters for Eq. (1) can be derived as J = 2aAex = −1.6475 × 10−21 J per link, DI = a2D = 9 × 10−23 J per link and Ka = a3K = 7.25 × 10−24 J per atom. The above exemplary material system has similar properties to the perovskite structure KMnF331,42, with an exchange constant lower than the experimental value43 to facilitate the formation of the bimeron clusters. On the other hand, we demonstrate that the bimeron solitons and clusters can also exist in the synthetic antiferromagnets composed of Co based alloy (cf. Supplementary Note 6). In addition, similar spin textures have been experimentally observed in the α-Fe2O3 thin film with a Pt over-layer44. These results suggest the possibility to stabilize bimerons in a wide range of material systems.

Stabilization of AFM bimeron solitons and their current-driven dynamics

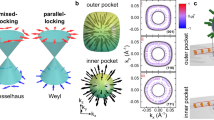

Similar to the AFM skyrmions, the magnetic topology of the AFM bimeron is defined by the Néel topological number Qn = (1/4π)∫dxdy[n ⋅ (∂xn × ∂yn)], with the uniform ground state nX = (1, 0, 0). Figure 1a shows the real-space spin texture of the AFM bimeron soliton with Qn = +1, which is formed by a circular AFM meron and a crescent-shaped AFM antimeron. The corresponding Néel vector components are shown in Fig. 1b–d, and the structural feature is clearly illustrated by nZ, which indicates a shape-defined magnetic topological dipole. We define the vector pointing from the perpendicular sublattices located in the circular meron part to that in the crescent-shaped antimeron part as the bimeron polarity pBM, which is parallel to the in-plane magnetic easy axis.

Compared with the FM skyrmion, the AFM skyrmion can be manipulated by spin current with higher mobility and no skyrmion Hall effect37,38,39. The AFM bimeron shares similar merits, while exhibiting obvious anisotropic dynamics on the other hand. In this part, we derive the steady motion velocity of the AFM bimeron based on Thiele’s approach45,46, and systematically investigate the dynamics driven by current with in-plane polarization (CIP) and current with out-of-plane polarization (COP). The former case can be realized by utilizing the spin Hall effect in antiferromagnet/heavy metal heterostructures, and the latter case corresponds to the spin-transfer torque originating from the out-of-plane current polarized by a perpendicularly fixed magnetic layer.

Taking the damping-like spin torques into account, the dynamics of the net magnetization m and the Néel vector n obey the following two coupled equations47,48

where γ and α are the gyromagnetic ratio and the damping constant. \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\,=\,-\delta {\mathcal{H}}/{\mu }_{\text{0}}{M}_{{\rm{s}}}\delta {\bf{m}}\) and \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{n}}}\,=\,-\delta {\mathcal{H}}/{\mu }_{\text{0}}{M}_{{\rm{s}}}\delta {\bf{n}}\) are the effective fields. \({{\bf{T}}}_{{\rm{nl}}}\,=\,(\gamma {{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\,-\,\alpha \dot{{\bf{m}}})\,\times\,{\bf{m}}\) is the higher-order nonlinear term47. p is the direction of current polarization. Hd = jℏP/(2μ0eMstZ) is the equivalent field of spin torque, with j being the charge current density, ℏ the reduced Planck constant, P the spin polarization efficiency, μ0 the vacuum permeability constant, e the elementary charge, and tZ = a the AFM layer thickness.

Based on Eqs. (3a), (3b), the steady motion speed of the AFM bimeron soliton can be semianalytically expressed as

where dij = ∫dxdy(∂in ⋅ ∂jn) is the component of the dissipative tensor d, and ui = ∫dxdy[(n × p) ⋅ ∂in] relates to the force induced by the damping-like spin torque45. The detailed derivation of the above equation is given in Supplementary Note 2. Equation (4) applies for not only bimeron solitons, but also bimeron clusters with higher Qn, which will be discussed later.

One of the key features of the AFM bimeron soliton is its anisotropic dynamics excited by CIP. Figure 2a shows the motion speed of the AFM bimeron soliton with Qn = +1 as a function of θp, the angle between the in-plane p and the +X-axis, with a varying current density j. Here, the speed of the AFM bimeron soliton is first obtained by numerically tracking its guiding center (see “Methods” section), and then comparing with Eq. (4). We assume the spin polarization efficiency P = 0.1, and for a moderate current with j = 5 × 1010 A m−2, the maximum speed is reached at θp = 90° or 270°. The one-fold anisotropic dynamics reflect the in-plane nature of the magnetic bimeron, which acquires the largest spin torque when p is orthogonal to the magnetic easy axis. On the other hand, the mobility for θp = 0° or 180° is due to the asymmetric structure of the soliton, which is absent for the symmetric AFM bimeron stabilized by anisotropic DMI33. As the current density increases to 1 × 1011 A m−2, and further to 2 × 1011 A m−2, the strong spin torques deform the bimeron soliton, leading to the two-fold anisotropic dynamics. In particular, the spin textures of an AFM bimeron for j = 2 × 1011 A m−2 with varying θp are shown in Fig. 2b to illustrate the current-induced deformations. A significant constriction/expansion can be observed when θp = 90°/270°, which leads to a lower/higher motion speed of the soliton. On the other hand, only a slight tilt of spin textures is observed when θp = 0° or 180°. Here, we note that the deformation of an AFM bimeron soliton involves the change of effective AFM mass tensor \({{\bf{M}}}_{\text{eff}}\,=\,{{\mu }_{0}}^{2}{{M}_{{\rm{s}}}}^{2}{t}_{{\mathrm{Z}}}{\bf{d}}{\lambda }^{-1}{\gamma }^{-2}/2\), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

a Steady motion speed of an AFM bimeron soliton driven by CIP as a function of the angle θp between the in-plane p and the +X-axis. b Deformations of an AFM bimeron soliton induced by CIP with j = 2 × 1011 A m−2, when θp = 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°, respectively. The directions of p and the velocity v are denoted by the black and the green arrows, respectively. c θv as a function of θp when CIP with j = 5 × 1010 A m−2 is applied. d Steady motion speed of an AFM bimeron soliton driven by COP as a function of j. Data in a, c, and d are obtained using both micromagnetic simulations and the semi-analytical approach described by Eq. (4).

We next define the motion direction of the AFM bimeron soliton by θv, the angle between the velocity v and the +X-axis. Figure 2c shows θv obtained by both Eq. (4) and the numerical simulations as a function of θp. CIP with a small j is adopted to exclude the influences from the spin torque-induced deformation. The nonlinear dependence of θv on θp is reminiscent of the skyrmion Hall effect, which demonstrates a transverse drift of ferromagnetic skyrmions with respect to the charge current flow. For the AFM bimeron soliton, the drifting is due to the asymmetric spin structure rather than the Magnus force, which is absent in the AFM system. It is found that this effect tends to deflect the motion of the bimeron soliton to the direction of the magnetic easy axis.

Another mechanism to drive the AFM bimeron is to utilize the COP, i.e., p = (0, 0, 1). With this configuration, the spin torque will be exerted on the in-plane topological core of AFM bimeron soliton, and thus lead to a steady motion along the direction eY. Figure 2d shows the speed obtained by Eq. (4) and the numerical simulations with P = 0.1. The dynamics excited by COP is relativistic, which is different from the above mentioned CIP case. As the current density further increases, the speed of the AFM bimeron gradually saturates to the maximum spin-wave group velocity, and manifests the Lorentz invariance (cf. Supplementary Fig. 3), which has been theoretically demonstrated for AFM skyrmions31,42 and domain walls49. In addition, we note that symmetric magnetic skyrmions are unresponsive to COP8.

Formation of bimeron clusters

The bound state of skyrmions has been predicted and observed in chiral ferromagnets50,51,52,53, frustrated materials18,25, and liquid crystals26. Despite the intriguing physics, it is important to find effective methods to manipulate these aggregated topological structures. In this part, we demonstrate the stabilization of the AFM bimeron clusters with high Qn in chiral antiferromagnetic thin films. The formation of these AFM clusters involves the rearrangement of topological structures, and leads to remarkable changes in both static and dynamical characteristics. Moreover, they have high mobility as generic AFM quasiparticles, making them ideal building blocks for AFM spintronic devices.

We first demonstrate the anisotropic interactions between two bimeron solitons with Qn = +1, as shown in Fig. 3a. For the simulations, we fix the spins at the topological center of each soliton, and minimize the system energy with this constraint. By varying the distance dp between the fixed cells along the direction defined by the angle φ, as illustrated by the inset of Fig. 3a, the effective interaction between the solitons can be derived from the variation of the total energy of the system54. For φ = 0°, the system energy rapidly increases as the bimerons approach each other, demonstrating a repulsive interaction. And the bimerons finally collapse at the separation distance dp = 18 nm due to the constriction, as indicated by the orange line. When φ increases, the interaction gradually changes from repulsive to attractive. For φ = 90°, a shallow potential well can be observed at dp = 22 nm, as indicated by the red line. Closer approach of the bimeron solitons leads to the formation of a bimeron dimer, which is indicated by a sudden drop of the energy at dp = 19 nm. To further investigate the formation of the bimeron dimer, we set φ = 90° and vary the strength of DMI, and its influence on the interaction between bimeron solitons is shown in Fig. 3b. For D = 0.34 mJ m−2, the interaction is repulsive. In this case the energy barrier prohibits the merging of bimeron solitons, and both of them collapse at dp = 13 nm. As D increases, the energy barrier vanishes, and finally leads to the spontaneous formation of the bimeron dimer, as indicated by the pink (D = 0.37 mJ m−2) and green (D = 0.38 mJ m−2) lines. Meanwhile, the merging distance and the bonding energy also increase with D. However, for higher D, the bimeron soliton tends to extend in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic easy axis, and relaxes to a domain wall pair, as demonstrated in Supplementary Note 4. This phenomenon is similar to the case for skyrmions in the perpendicular AFM system, which narrows the stability region of the solitons55.

a System energy as functions of the relative positions of two AFM bimeron solitons. dp is the distance between the solitons, φ is the azimuth with respect to the +X axis, and their definitions are illustrated in the inset. b System energy as a function of dp, with the interfacial DMI constant D varies from 0.34 to 0.38 mJ m−2. The formation of the AFM bimeron dimer is observed when D > 0.35 mJ m−2, which is indicated by a sudden drop of the system energy. c, d The Néel topological density qn distribution of an AFM bimeron soliton (Qn = +1) and a dimer (Qn = +2). e, f The profile of qn, nX, and nZ along the translational center (nY = 0) of the AFM bimeron soliton and dimer. The topological core of the AFM bimeron soliton is featured by in-plane spins with nX = 1, while that of the AFM bimeron dimer is featured by out-of-plane spins with nZ = 1.

Figure 3c, d show the spatial distribution of normalized Néel topological charge density qn = n ⋅ (∂xn × ∂yn) of the AFM bimeron soliton and dimer, respectively. We note that the formation of a dimer involves the merging of topological cores as shown in Fig. 3d, which indicates essential changes of the spin textures. In contrast, the topological cores remain protected for skyrmions in a bound state18. Figure 3e, f compare the profiles of Néel vector components and qn along the translational center line (nY = 0) of the bimeron soliton and dimer. The magnetic topology of bimeron soliton is represented by the in-plane sublattice spins (nX = −1), on the other hand, that of bimeron dimer is represented by the out-of-plane ones (nZ = −1). The reorientation of topology-representative spins is another feature identifying the formation of a bimeron dimer.

Due to the translational attractive interaction between the same solitons, they can accumulate along the direction perpendicular to the magnetic easy axis, and thus form AFM bimeron clusters with a wide range of Qn. Figure 4a compares the energy composition of bimeron clusters and the isolated bimeron solitons with the same Qn up to 20. There are two features worth-noting. Firstly, DMI prefers the formation of bimeron clusters rather than isolated bimeron solitons, as indicated by the green lines. Secondly, the stabilization of bimeron soliton is mainly determined by the competition between AFM exchange and DMI, while the magnetic anisotropy plays a minor role, as indicated by the lines with hollow symbols. However, the formation of bimeron clusters significantly increases the magnetic anisotropy energy, as indicated by the blue lines. As a result, we note that the stabilization of bimeron solitons and clusters may not be mutually guaranteed. Figure 4b shows the energy difference \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{diff}}}\) between bimeron clusters with Néel topological number Qn and Qn − 1. As Qn increases, \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{diff}}}\) quickly drops and then converges to a value smaller than the energy of an isolated bimeron soliton, which indicates the possibility to stabilize AFM bimeron clusters with an arbitrary Qn. Figure 4c, d show the real-space spin textures and Z component of Néel vectors of the bimeron clusters with Qn ranging from +2 to +6.

a Energy composition of the clustered and isolated bimerons vs. Qn. \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{exch}}}\), \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{anis}}}\), \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{DMI}}}\) are the energy contributions from the AFM exchange, magnetic anisotropy and DMI, respectively. b Energy difference between clusters with neighboring Néel topological numbers vs. Qn. c Real-space spin vectors and d Z component of Néel vectors of bimeron clusters with Qn ranging from +2 to +6.

Current-driven dynamics of bimeron clusters

Similar to the solitons, the AFM bimeron clusters can also be effectively manipulated by spin currents. We adopted j = 1 × 1010 A m−2 to avoid the deformation, and the calculated speeds of bimeron clusters driven by CIP and COP are shown in Fig. 5a, where good agreements between Eq. (4) and the numerical simulations can be observed. For the CIP-driven case, the AFM bimeron clusters have anisotropic dynamics similar to the soliton, and prefer the motion along the magnetic easy axis. As Qn increases, the speed driven by CIP nonlinearly increases, as indicated by the solid lines. However, the speed driven by COP decreases, as indicated by the green dashed line. We further calculated the strength of the effective spin torque force (FST,i = −μ0HdMstZui) as a function of Qn, and the results are shown in Fig. 5b. FST increases almost linearly with Qn for the CIP-driven cases, and well explains the anisotropic dynamics observed in Fig. 5a. In contrast, for the COP-driven case, the effective force remains constant when Qn ≥ 2. Since the accumulation of Qn will increase the dissipation and the effective mass, but not the effective driving force, the speed of AFM bimeron clusters with higher Qn tends to decrease.

a The steady motion speeds of the AFM bimeron clusters excited by CIP and COP. The results are obtained using both micromagnetic simulations and the semianalytical approach described by Eq. (4), with j = 1 × 1010 A m−2 and P = 0.1. b The corresponding effective spin torque forces.

Coexistence of topological counterparts and current-driven topology modification

The topological variety of the bimeron clusters can be further enriched because their counterparts with opposite Néel topological number Qn can coexist within the same AFM background. In order to understand this phenomenon, we analyze the AFM energy and the Néel topological number of the bimeron cluster by group symmetry. We use \({({S}_{{\mathrm{X}}},{S}_{{\mathrm{Y}}},{S}_{{\mathrm{Z}}})}_{{\rm{A}}}\) to denote the spin vectors of the bimeron A, which are operated as follows,

and then we get the spin vectors of bimeron B. The above operation is performed in the discrete coordinate system (cf. Supplementary Fig. 1), and the transformation to the continuum coordinate system leads to

The Néel vector and the net magnetization of the bimeron B are obtained as

On the other hand, the operation in Eq. (5) will cause the changes in the spatial derivatives of the AFM Néel vector,

Based on Eqs. (7) and (8), we get

Combining Eqs. (2), (7), and (9), it is found that the AFM energy of the bimeron A is the same as that of bimeron B, while they have the opposite Néel topological number Qn. Thus we prove the coexistence of AFM bimeron topological counterparts. Based on a similar approach, we also demonstrate in Supplementary Note 5 that for the clusters with opposite Qn, the CIP leads to their motions in the same direction, while COP to the opposite directions.

Compared with the thin films having perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, the forms of topological quasiparticles allowed by the in-plane AFM system are significantly enriched, making the bimeron clusters ideal multibit data carriers. Moreover, through the merging/annihilation of similar/opposite bimeron clusters, their Néel topological numbers can be easily modified. Figure 6 demonstrates the current-driven merging and annihilation process of AFM bimeron clusters. Here we adopted j = 1 × 1010 A m−2, P = 0.1, and use COP as the driving force, which leads to the most significant speed differences between clusters with different Qn. To demonstrate the merging of the similar clusters, a bimeron soliton with Qn = +1 and a cluster with Qn = +3 are aligned in the direction perpendicular to the in-plane magnetic easy axis. Then COP is applied to drive both the particles in the −Y direction. Due to their speed difference (about 36 m s−1 according to Fig. 5a), the bimeron soliton catches up with the cluster at about 200 ps, and finally they merge to a new cluster with Qn = +4 (cf. Supplementary Movie 1). After the merging of bimeron soliton and cluster, the total energy of the system decreases by about 160 K. To demonstrate the annihilation of the opposite clusters, a soliton with Qn = −1 and a cluster with Qn = +2 are used, and a slight misalignment is introduced to facilitate their annihilation, as shown in Fig. 6b. When COP is applied, the soliton and the cluster move toward each other. The annihilation happens at about 200 ps, with a significant drop of system energy (about 2600 K), which leads to a quick burst of spin waves, and finally the soliton with Qn = +1 remains (cf. Supplementary Movie 2). Based on the varied Néel topological numbers, we note that AFM bimeron clusters actually provide a full set of signed integers, and the above-mentioned processes can be regarded as the analogies of summation “3 + 1” and subtraction “2 − 1”. In this way, the current-driven dynamics of AFM bimeron clusters reveal an appealing path towards magnetic topology-based computing.

a Merging of the soliton with Qn = +1 and the cluster with Qn = +3. b Annihilation of the soliton with Qn = −1 and the cluster with Qn = +2. The upper pannels of a and b are the snapshots of the Néel vector distribution at specific simulation time t with an interval of 100 ps, the lower pannels record the system energy during the merging/annihilation process.

In summary, this study demonstrates the stabilization of AFM bimeron clusters with a wide range of Néel topological numbers of different sign in antiferromagnetic thin films with interfacial DMI, and that they exhibit rich and versatile current-driven dynamics. Such findings indicate that AFM bimerons may serve as an ideal candidate to investigate skyrmion-related physics, such as particle interaction, attraction, repulsion, bonding, and mutual annihilation.

From an applied perspective, through the processes of particle merging and annihilation driven by spin currents, the Néel topological number of the bimeron clusters can be easily modified, revealing an appealing path towards magnetic topology-based computing. The AFM bimeron cluster may be utilized to unify multibits data creation, transmission, storage, and computation within the same material system, paving the way for innovative data manipulation paradigms.

Methods

Atomistic spin dynamics simulations

In this work, we use the open-source micromagnetic simulator MuMax356 for the modeling of the Heisenberg AFM thin film. While MuMax3 is developed as a micromagnetic simulator for ferromagnetic materials, the finite difference implementation of the Heisenberg-type exchange on the nearest neighbors is also suitable for AFM systems with a simple cubic lattice. By equating the mesh size to the lattice constant, the spin dynamics of the system can be reasonably solved, and the obtained spin structure of the bimeron soliton is identical to that obtained using Vampire57, which is an open source atomistic simulator, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. These results suggest that on the atomistic-scale, the Hamiltonians involved in our system, including the Heisenberg exchange, the magnetic anisotropy and the interfacial DMI, are handled in the same way in MuMax3 and Vampire.

We use currents with in-plane and out-of-plane polarizations to excite the dynamics of the AFM bimerons. In both cases, the currents will induce antidamping Néel-order spin–orbit torque on the AFM sub-lattices, with the form Sk(l) × (Sk(l) × p)58. This configuration is self-implemented in MuMax3, and can be directly used without changing the source code. Numerically, the guiding center (rx, ry) is used to track the position of AFM bimeron soliton and clusters, which is defined by

And the velocity is calculated by \(({v}_{x},{v}_{y})\,=\,({\dot{r}}_{x},{\dot{r}}_{y})\).

We note that MuMax3 is only used to obtain the AFM spin configurations, based on which the system energy, the topological charge density and other quantities involving magnetization gradient are calculated by self-developed postprocessing tools.

Data availability

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code of MuMax3 is available at http://mumax.github.io/. The source code of VAMPIRE is available at https://vampire.york.ac.uk/.

References

Bogdanov, A. N. & Yablonskii, D. A. Thermodynamically stable "vortices” in magnetically ordered crystals. The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 68, 101–103 (1989).

Zhou, Y. Magnetic skyrmions: intriguing physics and new spintronic device concepts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 210–212 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Skyrmion-electronics: writing, deleting, reading and processing magnetic skyrmions toward spintronic applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 143001 (2020).

Fert, A., Reyren, N. & Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17031 (2017).

Kang, W., Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Zhao, W. Skyrmion-electronics: an overview and outlook. Proc. IEEE 104, 2040–2061 (2016).

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Rößler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Woo, S. et al. Observation of room-temperature magnetic skyrmions and their current-driven dynamics in ultrathin metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 15, 501–506 (2016).

Ma, C. et al. Electric field-induced creation and directional motion of domain walls and skyrmion bubbles. Nano Lett. 19, 353–361 (2018).

Hu, J. M., Yang, T. & Chen, L. Q. Strain-mediated voltage-controlled switching of magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. NPJ Comput. Mater. 4, 62 (2018).

Kim, S. K. Dynamics of bimeron skyrmions in easy-plane magnets induced by a spin supercurrent. Phys. Rev. B 99, 224406 (2019).

Göbel, B., Mook, A., Henk, J., Mertig, I. & Tretiakov, O. A. Magnetic bimerons as skyrmion analogues in in-plane magnets. Phys. Rev. B 99, 060407(R) (2019).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Transformation between meron and skyrmion topological spin textures in a chiral magnet. Nature 564, 95–98 (2018).

Gao, N. et al. Creation and annihilation of topological meron pairs in in-plane magnetized films. Nat. Commun. 10, 5603 (2019).

Kolesnikov, A. G. et al. Composite topological structure of domain walls in synthetic antiferromagnets. Sci. Rep. 8, 15794 (2018).

Leonov, A. O. & Kézsmárki, I. Asymmetric isolated skyrmions in polar magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 96, 014423 (2017).

Kharkov, Y. A., Sushkov, O. P. & Mostovoy, M. Bound states of skyrmions and merons near the Lifshitz point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 207201 (2017).

Zhang, X., Ezawa, M. & Zhou, Y. Magnetic skyrmion logic gates: conversion, duplication and merging of skyrmions. Sci. Rep. 5, 9400 (2015).

Lin, S.-Z., Saxena, A. & Batista, C. D. Skyrmion fractionalization and merons in chiral magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 91, 224407 (2015).

Ezawa, M. Compact merons and skyrmions in thin chiral magnetic films. Phys. Rev. B 83, 100408(R) (2011).

Murooka, R., Leonov, A. O., Inoue, K. & Ohe, J. Current-induced shuttlecock-like movement of non-axisymmetric chiral skyrmions. Sci. Rep. 10, 396 (2020).

Zarzuela, R., Bharadwaj, V. K., Kim, K.-W., Sinova, J. & Everschor-Sitte, K. Stability and dynamics of in-plane skyrmions in collinear ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 101, 054405 (2020).

Tong, Q., Liu, F., Xiao, J. & Yao, W. Skyrmions in the Moiré of van der Waals 2D magnets. Nano Lett. 18, 7194–7199 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Skyrmion dynamics in a frustrated ferromagnetic film and current-induced helicity locking-unlocking transition. Nat. Commun. 8, 1717 (2017).

Foster, D. et al. Two-dimensional skyrmion bags in liquid crystals and ferromagnets. Nat. Phys. 15, 655–659 (2019).

Duzgun, A., Selinger, J. V. & Saxena, A. Comparing skyrmions and merons in chiral liquid crystals and magnets. Phys. Rev. E 97, 062706 (2018).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Gomonay, O., Baltz, V., Brataas, A. & Tserkovnyak, Y. Antiferromagnetic spin textures and dynamics. Nat. Phys. 14, 213–216 (2018).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Barker, J. & Tretiakov, O. A. Static and dynamical properties of antiferromagnetic skyrmions in the presence of applied current and temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 147203 (2016).

Dohi, T., DuttaGupta, S., Fukami, S. & Ohno, H. Formation and current-induced motion of synthetic antiferromagnetic skyrmion bubbles. Nat. Commun. 10, 5153 (2019).

Shen, L. et al. Current-induced dynamics and chaos of antiferromagnetic bimerons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 037202 (2020).

Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ezawa, M. Antiferromagnetic skyrmion: stability, creation and manipulation. Sci. Rep. 6, 24795 (2016).

Shen, L. et al. Current-induced dynamics of the antiferromagnetic skyrmion and skyrmionium. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 064033 (2019).

Legrand, W. et al. Room-temperature stabilization of antiferromagnetic skyrmions in synthetic antiferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 19, 34–42 (2019).

Litzius, K. et al. Skyrmion Hall effect revealed by direct time-resolved X-ray microscopy. Nat. Phys. 13, 170–175 (2017).

Jiang, W. et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 13, 162–169 (2017).

Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ezawa, M. Magnetic bilayer-skyrmions without skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 10293 (2016).

Rohart, S. & Thiaville, A. Skyrmion confinement in ultrathin film nanostructures in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 184422 (2013).

Tveten, E. G., Müller, T., Linder, J. & Brataas, A. Intrinsic magnetization of antiferromagnetic textures. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104408 (2016).

Salimath, A., Zhuo, F., Tomasello, R., Finocchio, G. & Manchon, A. Controlling the deformation of antiferromagnetic skyrmions in the high-velocity regime. Phys. Rev. B 101, 024429 (2020).

Pickart, S. J., Collins, M. F. & Windsor, C. G. Spin-wave dispersion in KMnF3. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 1054 (1966).

Jani, H. et al. Half-skyrmions and bimerons in an antiferromagnetic insulator at room temperature. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.12699

Thiele, A. A. Steady-state motion of magnetic domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 30, 230–233 (1973).

Tveten, E. G., Qaiumzadeh, A., Tretiakov, O. A. & Brataas, A. Staggered dynamics in antiferromagnets by collective coordinates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 127208 (2013).

Hals, K. M. D., Tserkovnyak, Y. & Brataas, A. Phenomenology of current-induced dynamics in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107206 (2011).

Velkov, H. et al. Phenomenology of current-induced skyrmion motion in antiferromagnets. New J. Phys. 18, 075016 (2016).

Shiino, T. et al. Antiferromagnetic domain wall motion driven by spin-orbit torques. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 087203 (2016).

Zhao, X. B. et al. Direct imaging of magnetic field-driven transitions of skyrmion cluster states in FeGe nanodisks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4918–4923 (2016).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Aggregation and collapse dynamics of skyrmions in a non-equilibrium state. Nat. Phys. 14, 832–836 (2018).

Göbel, B., Henk, J. & Mertig, I. Forming individual magnetic biskyrmions by merging two skyrmions in a centrosymmetric nanodisk. Sci. Rep. 9, 9521 (2019).

Du, H. F. et al. Interaction of individual skyrmions in a nanostructured cubic chiral magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 197203 (2018).

Rózsa, L. et al. Skyrmions with attractive interactions in an ultrathin magnetic film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 157205 (2016).

Bessarab, P. F. et al. Stability and lifetime of antiferromagnetic skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 99, 140411(R) (2019).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Evans, R. F. L. et al. Atomistic spin model simulations of magnetic nanomaterials. J. Phys. Condens. Mater 26, 103202 (2014).

Železný, J. et al. Relativistic Néel-order fields induced by electrical current in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 157201 (2014).

Acknowledgements

X.L. acknowledges the support by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2019A1515111110). X.Z. acknowledges the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12004320), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2019A1515110713), and Presidential Postdoctoral Fellowship of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen (CUHKSZ). M.E. acknowledges the support from the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. JP18H03676, JP17K05490, and JP15H05854) and the support from CREST, JST (Grant Nos. JPMJCR16F1 and JPMJCR1874). O.A.T. acknowledges the support by the Australian Research Council (Grant No. DP200101027), the Cooperative Research Project Program at the Research Institute of Electrical Communication, Tohoku University (Japan), and by the Ministry of Science and Technology Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of NUST “MISiS” (No. K2-2019-006), implemented by a governmental decree dated 16th of March 2013, N 211. X.X. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51871137 and 61434002), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFB0405604). M.M. and M.K. acknowledge support from National Science Center of Poland No. 2018/30/Q/ST3/00416. Y.Z. acknowledges the support by the President’s Fund of CUHKSZ, Longgang Key Laboratory of Applied Spintronics, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11974298 and 61961136006), Shenzhen Fundamental Research Fund (Grant No. JCYJ20170410171958839), and Shenzhen Peacock Group Plan (Grant No. KQTD20180413181702403). Y.X. acknowledges the support by the State Key Program for Basic Research of China (Grant No. 2014CB921101, 2016YFA0300803), NSFC (Grants No. 61427812, 11574137), Jiangsu NSF (BK20140054), Jiangsu Shuangchuang Team Program and the UK EPSRC (EP/G010064/1). The atomistic simulations were undertaken on the VIKING cluster, which is a high performance compute facility provided by the University of York. We are grateful for computational support from the University of York High Performance Computing service, VIKING and the Research Computing team.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., X.Z., and L.S. conceived the idea. Y.Z., X.X., and M.K. coordinated and supervised the work. X.L. and J.X. performed the micromagnetic simulation. L.S. and Y.B. carried out the theoretical analysis. J.W., Y.X., R.F.L.E., and R.W.C. performed the atomistic simulation. X.L. and L.S. drafted the study with the input from M.E., O.A.T., M.M., and R.W.C. All the authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript. X.L., L.S. and Y.B. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Shen, L., Bai, Y. et al. Bimeron clusters in chiral antiferromagnets. npj Comput Mater 6, 169 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00435-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00435-y

This article is cited by

-

Collective variable model for the dynamics of liquid crystal skyrmions

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Electrical engineering of topological magnetism in two-dimensional heterobilayers

npj Spintronics (2024)

-

Antiferromagnetic half-skyrmions and bimerons at room temperature

Nature (2021)

-

Meron-like topological spin defects in monolayer CrCl3

Nature Communications (2020)