Abstract

The effects of incident energetic particles, and the modification of materials under irradiation, are governed by the mechanisms of energy losses of ions in matter. The complex processes affecting projectiles spanning many orders of magnitude in energy depend on both ion and electron interactions. Developing multi-scale modeling methods that correctly capture the relevant processes is crucial for predicting radiation effects in diverse conditions. In this work, we obtain channeling ion ranges for tungsten, a prototypical heavy ion, by explicitly simulating ion trajectories with a method that takes into account both the nuclear and the electronic stopping power. The electronic stopping power of self-ion irradiated tungsten is obtained from first-principles time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT). Although the TDDFT calculations predict a lower stopping power than SRIM by a factor of three, our result shows very good agreement in a direct comparison with ion range experiments. These results demonstrate the validity of the TDDFT method for determining electronic energy losses of heavy projectiles, and in turn its viability for the study of radiation damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to accurately predict range profiles of energetic ions in solids is an important aspect of the understanding of radiation effects, relevant to numerous applications in materials modification, including semiconductor processing, energy production,1 and medicine,2 as well as for the development of nuclear technology.3 While the stopping of ions in matter has been the focus of significant scientific effort over many decades (for reviews see, e.g., refs. 4,5,6), many key questions remain unanswered, especially concerning the role of electrons in the low-energy regime.

The processes by which ions slow down and deposit energy when traveling through a solid can essentially be separated into two distinct phenomena: energy losses due to interactions with atomic nuclei in the target material and energy losses due to interactions with electrons, termed nuclear and electronic stopping, respectively. Electronic stopping is the dominant mechanism for projectiles in the MeV–GeV energy range. In the lower energy range (~100 keV), which is the focus of this study, nuclear stopping dominates the slowing down of heavy ions. Nevertheless, electronic stopping power remains significant in this energy range, to a degree that we will quantify in this paper. This is especially true in the case of channeling ions, where nuclear stopping is strongly reduced,7,8 as well as in the quenching stage of heat spikes, that develop from collision cascades in primary radiation damage events.3,9

Channeling refers to the phenomenon where projectiles travel between atomic rows and planes in a crystalline material,10,11 leading to implantation depths exceeding the average range for random directions by up to an order of magnitude.8 These effects are crucial in monocrystalline materials, but may also give rise to a long tail in the distribution of implanted ions in polycrystalline materials.12 The deeper penetration in channeling directions is a consequence of the lower nuclear stopping (due to the lattice structure)12 and the lower electronic stopping (due to the lower electron density in the channel).13,14 Hence, accurately predicting channeling ranges requires accounting for both nuclear and electronic interactions with the projectile.

The SRIM (stopping and range of ions in matter) software package15 is widely used, e.g., for the calculation of ion implantation profiles, as well as the determination of the deposited damage energy and, from that, the standard displacements per atom (dpa) measure of radiation dose.16 The SRIM code provides an implementation of the theories of both electronic and nuclear stopping for any given ion in any amorphous target material. Since neither the calculation of the nuclear nor the electronic stopping power includes any spatial information, either regarding the ordered lattice structure of the target material, or the local electronic structure, the calculations fail systematically for channeled ions.12 Furthermore, since SRIM model parameters are fitted to experiments, predictions are sensitive to experimental errors, for example, in separating electronic and nuclear stopping contributions.17 Hence, values obtained from SRIM carry numerous uncertainties, especially for heavy ions in the low-velocity range.5

In collision cascades, projectiles travel in random directions, and recoils initiated in the bulk, for example, by neutron impacts or as secondary recoils in cascades, seldom the channel. However, atoms that have kinetic energies of the order of eV can exist in the thousands in the later stages of energetic cascades. As a result, the treatment of electronic stopping in the low-energy limit in atomistic cascade simulations has a significant effect on the predictions of the primary damage, especially in heavy elements with dense heat spikes, such as tungsten.18,19 In the heat-spike stage of collision cascades, atoms form a local structure resembling that of the liquid,20 with a local density similar to that of the unperturbed solid. The energetic atoms in the heat spike thus experience an electron density close to that of equilibrium atoms. Since the electron density seen by these atoms is lower than that visited on average by penetrating ions, traditional electronic stopping models fail in this scenario,21 raising the need for more accurate models that take into account the local electronic structure and density. Tungsten (W) is currently the leading candidate material for plasma-facing components in the design of fusion reactors;22,23 therefore, understanding the mechanisms of radiation damage in W is crucial for the safe operation of future fusion power plants.

Relatively recently, time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) has been used to determine the electronic stopping for a number of projectile–target combinations.24,25,26,27,28,29,30 Unlike the free electron gas-based models,31 TDDFT explicitly takes into account the effects of inhomogeneity in electron density due to the underlying lattice structure, band structure,32 band gap,14 and core-state excitations.33,34,35 Furthermore, the charge state of the projectile need not be imposed in TDDFT calculations, but rather is an outcome of the method itself. Hence, TDDFT provides an ideal theoretical tool for a parameter-free determination of electronic stopping in a variety of conditions.

In this work, we have calculated the electronic stopping power of self-ion irradiated W within the TDDFT approach, and present a direct comparison of predictions based on TDDFT calculations with experimentally measured W ion ranges along the 〈100〉 channel in bulk W. Our TDDFT-based results of ion ranges show a very good agreement with experimental ion ranges, demonstrating the accuracy and predictive power of the TDDFT method of calculating electronic stopping, and its applicability to heavy transition metals, such as W.

Experimental investigation of the electronic stopping of channeled ions is possible in the low-velocity range due to the reduced nuclear stopping when compared with that of random trajectories. However, even in perfectly channeling conditions, nuclear stopping cannot be completely disregarded in the limit of low-projectile velocity. The comparative importance of nuclear and electronic stopping power has been explicitly investigated by Eriksson et al.36 from experimental ion ranges in the 〈100〉 direction in W. We use these data to make a direct comparison with the electronic stopping predicted by our TDDFT calculations.

Results and discussion

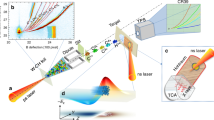

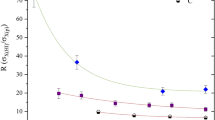

We have used TDDFT in the time-dependent Kohn–Sham formalism to determine the electronic stopping power of W ions in the 〈100〉 channel in W, as detailed in the Methods section. Figure 1 shows the nonadiabatic asymmetric variations (wake) in the electron density around the heavy W ion predicted by the TDDFT model. Our calculations yield a stopping power roughly linear in velocity, in the range of velocities studied here, as expected of a metal. We compare our results to the predictions from SRIM, as well as to the experimental results of Eriksson et al.36 As shown in Fig. 2, the TDDFT electronic stopping power is significantly lower than the SRIM values. Such lower value is to be expected based only on local electron density considerations,9 since SRIM values are targeted to amorphous materials, or to random trajectories, situations at which the relevant electron density is higher, while our calculations are in channeling conditions.

a Electronic stopping power of W in the 〈100〉 channel in W as a function of projectile velocity, determined with TDDFT, and compared with SRIM values for W in amorphous W. To show the relevance of deep semicore states,35 open triangles (“W20”) consider explicitly 4 f electrons in the projectile—a total of 20 explicit electrons instead of 12 valence electrons (“W12”), see the Methods section for details. b The TDDFT-determined electronic stopping of channeled W ions in W (square) compared with experimentally determined values of the electronic stopping power for various other species in the 〈100〉 channel in W (open circles). All values are for ions with v = 1.5 × 106 m/s (0.7 a.u.). Experimental points are taken from ref. 36, with the dotted lines drawn as a guide for the eye, sketching the Z1 oscillations (see text)

Taking the local electron density in the channel into account, theoretical predictions, e.g., of the Firsov model, improve agreement with experimental results in two distinct channels in W.36 Although the W ion is not one of those for which electronic stopping was determined directly in the reported original experiments, our value of Se = 14.15 × 10−14 eV cm2/atom at v = 1.5 × 106 m/s falls within the expected range compared with the experimental values for other ions (Fig. 2). The experimental results36 presented in Fig. 2 also clearly show a Z1 oscillation in the stopping power, which was later explained based on a consideration of the ionic radii.37

Eriksson et al. have reported the range of channeled W ions in W for a single projectile energy of 50 keV, finding a value of Rmax = 3289 Å for the 0.1% of ions that penetrate the deepest into the sample.36 Since this single data point did not allow a determination of the magnitude of the electronic stopping for the W ion, we instead use the measured range to make a direct comparison of the maximum range of channeled W ions in W predicted with the electronic stopping power from TDDFT. In this case, the contribution of nuclear stopping (or more generally ion–ion scattering) is non-negligible, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a, which compares the range of an ideally channeled ion, with nuclear and electronic stopping, to the distance traveled by a projectile subjected to purely electronic stopping as the retarding force. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, and as expected based on channeling theory11 and experiment,36 the magnitude of the nuclear stopping power in the channel is indeed negligible compared with the electronic stopping power. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 3a, the absolute range of a channeled ion is still strongly affected by the nuclear stopping contribution to the total stopping.

a The maximum range of a perfectly channeled ion, for initial kinetic energies above 0.1 keV, with, and without the ion–ion interaction contribution (responsible for nuclear stopping) to the slowing down of the ion. b The total and electronic stopping powers, obtained by differentiating the curves in a. The experimental ion energy of 50 keV36 is indicated with arrows in both plots

For the calculation of ranges with only electronic stopping, Newton’s equation of motion for the projectile was integrated with the electronic stopping power applied as a velocity-dependent antiparallel force, the strength of which was determined by interpolating the TDDFT values (Fig. 2a), and no nuclear interactions were active. For the range calculation with full nuclear and electronic stopping, the Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark (ZBL) repulsive potential4 was used to model the interactions between the projectile and atoms along the channel, and in addition, the electronic stopping was applied as an antiparallel force. The stopping power was calculated for ions with kinetic energy above 0.1 keV. However, a 1-keV ion only travels 37 Å along this idealized trajectory, and for kinetic energies below 1 keV, the concept of channeling becomes less applicable. In particular, the range becomes smaller than the spatial resolution of the experimental measurement. Also, the range of the ion quickly decreases to the order of the lattice parameter, and hence a quantitative value from computations becomes increasingly sensitive to the position along the channel. We include the computed values in the extreme low-energy range in Fig. 3 for the sake of academic interest. To obtain the total stopping power (shown in Fig. 3b), the curve in Fig. 3a was differentiated, following the experimental method of Eriksson et al., to yield S = ΔE/ΔR. As in experiments, this yields a curve which approaches the characteristic ∝E1/2 dependence of electronic stopping as the projectile energy increases. The same procedure was applied to the range curve for the distance traveled with only electronic stopping. The latter calculation recovers the interpolation of the input electronic stopping values, which are included in the plot for comparison.

Although the effective nuclear stopping power acting on (ideally) channeled W ions at 50 keV indeed appears negligible, compared with the magnitude of the electronic stopping power, the maximum predicted range at this energy nevertheless increases by 57% if nuclear stopping is disregarded. For reference, in an idealized channeling trajectory, i.e., straight down the exact center of the 〈100〉 channel, the distance traveled by a 50-keV W ion experiencing both ion–ion interactions (ZBL) and electronic stopping (with the magnitude predicted by our TDDFT calculations) is 3841 Å, while for motion retarded only by the TDDFT-predicted electronic stopping, a projectile with initial kinetic energy of 50 keV travels as much as 6045 Å. Of this, 940 Å is traveled by the ion after the kinetic energy has been reduced to 1 keV (compared with 37 Å under full stopping), due to the electronic stopping tending to zero in the low-velocity limit. This result underpins the critical importance of nuclear stopping while studying range profiles of channeled ions.

In an actual channeling experiment, ions rarely travel down the exact center of the channel, but rather oscillate between the neighboring atom rows. Hence, the nuclear scattering is stronger than for the ideally channeled trajectory presented above, resulting in an overall higher nuclear stopping, and as a result, the range is generally shorter than that plotted in Fig. 3. In this work, we simulate the ranges of realistic projectile trajectories using a molecular dynamics-based method, to explicitly account for the nuclear stopping contribution. Interactions of the projectile with the atoms in the target material are calculated using the full MD formalism, with the interaction described by the ZBL repulsive potential.4 Simulations thus take into account the crystal structure of the target material, and also explicitly include many-body interactions. The electronic stopping is included in the calculation as an extra antiparallel force acting on the projectile. To obtain a direct comparison with the experiments of Eriksson et al.,36 we simulated the ranges of ions incident on the bcc crystal at angles randomly chosen within 0.1° of the 〈100〉 direction.

Since the realistic projectile does not travel in a perfectly straight line down the center of the channel, the question arises of the variation in the impact parameter, and whether the electronic stopping obtained by TDDFT in the center of the channel is representative of the electronic stopping along the whole trajectory. To answer this, we have statistically analyzed the paths of the 260 most strongly channeled ions. We find that the projectile oscillates between the rows of atoms making up the edges of the channel, with a period of roughly 500 Å, in agreement with channeling theory.11 The experimentally measured range of channeling ions is given by the depth at which the range distribution sharply drops off to zero, and therefore is determined solely by the ions that channel the furthest. We find that these ions never leave their initial channel; thus, the prediction of the range of the channeled ions is unaffected by trajectories outside the central region of a channel.

When projected in the plane perpendicular to the channel, the trajectory of the channeled ion gives an indication of the electron density explored, which in turn defines the relative importance of the electronic stopping predicted for different regions of the channel. Typical trajectories, represented as probability distributions, are shown in Fig. 4. For the projectiles that travel the furthest, the trajectory typically deviates <0.4 Å from the channel midpoint. Over this region, the explored electron density remains within 0.01 a.u. of the central value (see Fig. 4). We note that recent results38 indicate that the electron density alone is not enough to fully characterize the local electronic stopping. Rather, shell and band structures in relation to the projectile velocity need to also be accounted for. For increasing velocities, deviations from the center of the channel can be expected to have an increasing effect, due to deeper core states being excited. Nevertheless, based on the study in Ni,38 as well as on our own calculations in W, ions in the velocity range studied here potentially display an increase in the effective electronic stopping by a nontrivial factor of around three for trajectories deviating from the center of the channel. Thus, the electron density described by the 12 explicit electrons, as shown in the top panel in Fig. 4, provides an indication of changes in the magnitude of the local stopping power. However, a full study of energy dissipation channels in random trajectories is beyond the purpose of this paper.

Lower panel: Two trajectory densities of strongly channeled ions in the W lattice (with lattice parameter a = 3.16 Å) projected in a perpendicular plane cut, on the left in a lattice with negligible thermal displacements, and on the right at 300 K. Green and purple balls represent atoms in different planes. Top panel: The electron density in the channel, plotted as a function of position (in terms of the lattice parameter a) perpendicularly across the midpoint of the channel, and across the channel over a point halfway between the channel midpoint and the nearest row of atoms, in the plane of the green atoms in the figure. By symmetry, the green line also represents the density across the midpoint of the channel 0.25 a below the plane of the green atoms

We have also investigated the effect of the thermal displacements of the target atoms on the channeled trajectories using a Debye model.39 We find that displacement disorder adds a non-perturbative element of randomness to the trajectories, increasing the average nuclear stopping and decreasing the range. Although this slightly widens the region visited by the projectiles, those that travel the furthest nevertheless remain within the constant electron density region of the channel. However, the increased probability of ejection from the channel qualitatively changes the differential range profile.

Figure 5 illustrates the range of impact parameters (defined as the perpendicular distance from the projectile to the nearest row of atoms) experienced by ions along a number of different trajectories. There is a clear correlation between the depth that a trajectory reaches, and the proximity of the trajectory to the neighboring atoms. The physical electronic stopping power Se = dE/dx will be stronger than that predicted by channeling TDDFT (Fig. 2a) for ions that pass nearer to the neighboring atoms;38 hence, the final depth of trajectories that see large distances Δx traveled at the low-impact parameter are likely overestimated in this work, where we have used the center-channel Se value. However, only the deepest 0.1% of ions contribute to the measured Rmax value, and for these, the impact parameter remains large throughout the trajectory, making the channeling assumption (for the TDDFT calculation) retrospectively valid. Hence, we conclude that an electronic stopping power that is independent of position is a valid approximation for the quantitative determination of the maximum range carried out in this study.

The range of impact parameters experienced by channeling ions. Each histogram shows the distance Δx (Å) traveled at various impact parameters (the perpendicular distance to the nearest host ion in the channel) for individual trajectories. For example, an ion reaching 3810 Å spends all the time at an impact parameter larger than 1.4 Å, (no more than 0.2 Å from the center of the channel) and traveling at most 550 Å in each of the discretized (binned) distances; an ion reaching 3262 Å spends all the time at an impact parameter larger than 1 Å, traveling no more than 200 Å at any particular impact parameter. For comparison, a perfectly channeled ion, exhibiting no deviation from the center of the channel, reaches 3840 Å. Ion trajectories included in the 0.1% determining the simulated Rmax are shown in yellow to red hues, while trajectories that reach a shallower depth, and hence do not contribute to the Rmax value, are shown in blueish hues. The total distance of each trajectory is indicated above the corresponding line. The histograms are shifted upward in steps of 200 Å for clarity

Figure 6 shows the simulated integral and differential range distributions for 50-keV W atoms in the 〈100〉 channel at 300 K, using the electronic stopping power predicted by TDDFT. For comparison, we have also plotted the range distributions simulated at various other temperatures. We note that the model for thermal fluctuations used in this work generates displacements that tend to zero at 0 K,39 and hence does not account for quantum mechanical zero-point vibrations. (It is used here at low temperature (T < TDebye) only as a model system to illustrate the effects of atom displacements on channeling trajectories.) We also plot the range distribution simulated at 300 K using the SRIM values for the electronic stopping, and show the effect of uniformly scaling the SRIM values toward the values predicted by TDDFT. Each curve is obtained from 1 million individual ion trajectories. The experimentally determined range Rmax, defined as the point where 0.1% residual activity is measured (i.e., 0.1% of the ions have reached a point beyond this depth), is indicated in the figure. The experimental measurement was performed at 300 K, and is reported to have an uncertainty of about 3%, indicated in the plot with a horizontal error bar.

Integral a and differential b ranges of 50-keV W ions in the 〈100〉 channel in W, using different values for electronic stopping, and different target temperatures. The experimental range Rmax36 is marked with a black dot, with the reported 3% uncertainty indicated with an error bar

The simulated range at 300 K is 5% deeper than the experimental Rmax, which is beyond the estimated uncertainty of the experimental measurement, but is nevertheless realistic when considering the differences between the experimental and simulation conditions. The experiments were conducted under normal vacuum conditions (as opposed to ultrahigh vacuum); hence, a thin layer of oxide (~10 Å) likely covered the tungsten sample.36 A surface oxide layer causes dispersion in the direction of the incident ions, such that even a few atom layers of oxide could give rise to a reduction in the depth of the measured Rmax value by a couple of percent for low-energy ions.8 In addition, as the repeated implantation progresses, the amount of lattice damage caused by the projectiles will steadily increase. It was shown by the same authors in a companion paper,40 that accumulated lattice damage can, for high doses, significantly decrease the maximum channeled range. In the case considered here, of 50-keV W ions incident on a W target, the damage is concentrated in the first 10 nm below the surface (corresponding to the first shallow peak in Fig. 6b, which gives the penetration depth of non-channeled ions). Although the total dose was kept relatively low,36 the highly damaged near-surface region can be expected to have a similar, and additional, dispersive effect as the thin surface oxide layer. In the simulations, we do not account for surface contamination, and the lattice is taken as the perfect bcc lattice, with only thermal vibrations misaligning the atomic rows. Therefore, a deeper range can be expected from simulation, even with an accurate electronic stopping, after the modeling simplifications. In addition, one cannot discount the possibility of local irradiation-induced heating occurring during the experiment, and the simulations show that even a 50° increase in temperature will decrease the range by 2%. Furthermore, the ZBL repulsive potential also has an uncertainty of up to about 10%,4 and while the largest errors appear at interatomic distances closer than those relevant for channeling trajectories,41 this may nevertheless lead to an uncertainty in the simulated total nuclear stopping. Considering these factors, and the fact that our simulation method has no fitted parameters, the agreement between experiment and simulation is very good.

The differential range distribution observed in experimental range measurements generally displays a characteristic double-peaked distribution for heavy ion projectiles in the energy range of 100’s of keV, which is not apparent in range distributions of lower-energy projectiles.36,40 We see the double-peaked distribution clearly in the simulated ranges of 50-keV W ions using the SRIM electronic stopping value. However, for decreasing electronic stopping power, the second peak is diminished, as the maximum distance the projectiles can travel increases. The double-peaked distribution is recovered when the displacement disorder is suppressed, as shown in Fig. 6, providing qualitative agreement with the characteristic distribution seen in experiments.40

Eriksson40 observes a slight decrease of Rmax at higher temperature, but notes that the magnitude of the shift is still roughly within the error of the measurement. This tacit conclusion that temperature effects are negligible is based on the reasoning that mainly electronic stopping causes the slowing down of “perfectly” channeled ions. From our simulations, however, we see that increased temperature affects the channeled trajectories (see Fig. 4), introducing a chaotic aspect as well as widening the transverse region that the ion visits, and thus increases the nuclear scattering of the projectile. This increases the contribution of the nuclear stopping also for strongly channeled ions, resulting in a decrease in Rmax with increasing temperature.

In conclusion, our TDDFT calculations yield a stopping power for W ions in the 〈100〉 channel in W, which ultimately gives a prediction of the maximum ion range in very good agreement with experiments. Agreement is found based on two different ways of extracting the value of the electronic stopping power from experiments. Both the simulated and experimentally deduced values are significantly lower than the average stopping power for random trajectories given by the predictions of SRIM and the Firsov model. Hence, the saturation of the predicted value of the electronic stopping power for an increased number of explicit core electrons, as seen in the TDDFT calculations in this work (triangles in Fig. 2a), provides strong evidence that the energy dissipation channels have been accounted for.35 Furthermore, convergence of the TDDFT calculations constituted a more dependable indication for a correct prediction in the collision cascade relevant projectile energy range, than comparison with the SRIM value, particularly in the crystallographic directionally dependent trajectories investigated here. This work demonstrates the applicability of the TDDFT method for determining the electronic stopping of heavy W projectiles in a W target, and the significant effect of the local environment on the magnitude of the stopping power.

Methods

The real-time TDDFT calculations determining the electronic stopping power were performed according to the method described in refs. 25,42, using the Qb@ll code,43 with custom time-dependent modifications.42,44 The adiabatic local density approximation (ALDA)45 was used to represent the exchange and correlation functional. While it has been shown that the nonlocality of the dynamical exchange and correlation potential in the linear-response regime has an effect in calculations of the electronic stopping of slow ions in a uniform electron liquid,46 the results of our work indicate that the magnitude of such corrections in the domain investigated here are below the sensitivity of applications to atomic dynamics, such as in the study of ion ranges. A practical advantage of the ALDA is that it is readily available in the context of real-time TDDFT.

A supercell was constructed with 108 atoms, arranged in 3 × 3 × 6 body-centered cubic unit cells, with the experimentally measured lattice constant of 3.16 Å.47 The W projectile was placed at the center of the 〈100〉 channel, for which a self-consistent ground state of the system was calculated using standard DFT. The projectile was then given a constant velocity down the center of the channel. Since the total time in these simulations is less than a few femtoseconds, the host ions do not have time to measurably relax or move, and were kept constrained to their equilibrium positions to simplify the analysis. The electronic stopping power was determined by the energy uptake of the electronic subsystem as a function of the projectile displacement.

Electrons are represented by time-evolving Kohn–Sham states. We used norm-conserving nonlocal pseudopotentials, factorized in the Kleinman–Bylander form48 to represent the ion–electron interaction. The electronic stopping convergence with respect to core electrons of the projectile was tested using 12 and 20 explicit electrons in the W pseudopotential. Ullah et al.35 recently showed, in a study of Ni, that, at large enough energy near the maximum of stopping, the deep core states of the projectile provide a critical contribution to the energy dissipation, while the core states of the target have less impact. As shown in Fig. 2, taking into account 12 explicit electrons for the W projectile was found to be an already good representation of the system in the velocity region (v < 1.0 a.u.) examined in this work. Kohn–Sham states (wavefunctions) are expanded in a plane-wave basis. After testing the convergence of electronic stopping power with respect to the cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis, a value of 140 Ry was used. The initial Kohn–Sham wavefunctions were evolved in time using the fourth- order Runge–Kutta integrator, as described in ref. 42. Forces and energy deposition were monitored to obtain the prediction of the electronic stopping power.6 A time step of 0.01 a.u. or smaller was used. Possible finite size effects were considered by increasing the size of the supercell, which did not significantly affect the resulting electronic stopping power.

Ion ranges were simulated using the MD-based method of the MDRANGE code.49 An initial simulation cell of 9 × 9 × 9 body- centered cubic unit cells with the experimental lattice constant a0 = 3.16 Å was created and replicated on-the-fly along the ion path as the ion progressed into the material during the simulation. Ions were initiated from random positions near the surface of the target, and the simulation was carried out until the ion kinetic energy had decreased to 1 eV. The interactions between the ions and the target atoms were modeled using the ZBL repulsive potential.4

Interactions between individual target atoms are disregarded in the MDRANGE method. However, initial thermal displacements from perfect lattice positions in the target material are implemented based on the Debye model, with a procedure described in detail in ref. 39. Hence, effects due to the instantaneous thermal displacements of target ions from the perfect lattice sites are captured. This method results in a computational efficiency approaching that of simulation methods based on the binary collision approximation (e.g., the method used in SRIM), while retaining the accuracy of full MD.49

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

A complete description of the MDRANGE code, including source code, is available online at http://beam.helsinki.fi/knordlun/mdh/mdh_program.html.

References

Hieslmair, H. et al. High throughput ion-implantation for silicon solar cells. Energy Procedia 27, 122–128 (2012).

Williams, J. & Buchanan, R. Ion implantation of surgical Ti6Al4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. 69, 237–246 (1985).

Was, G. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science: Metals and Alloys (Springer London, Limited, London, 2007).

Ziegler, J. F., Littmark, U. & Biersack, J. P. The Stopping and Range of Ions in Solids (Pergamon, New York, 1985).

Sigmund, P. Stopping power in perspective. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 135, 1–15 (1998).

Correa, A. A. Calculating electronic stopping power in materials from first principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 150, 291–303 (2018).

Piercy, G. R., Brown, F., Davies, J. A. & McCargo, M. Experimental evidence for the increase of heavy ion ranges by channeling in crystalline structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 10, 399–400 (1963).

Kornelsen, E. V., Brown, F., Davies, J. A., Domeij, B. & Piercy, G. R. Penetration of heavy ions of kev energies into monocrystalline tungsten. Phys. Rev. 136, A849–A858 (1964).

Caro, M., Tamm, A., Caro, A. & Correa, A. A. Role of electrons in collision cascades in solids. part i: Dissipative model. Phys. Rev. B (in press).

Robinson, M. T. & Oen, O. S. The channeling of energetic atoms in crystal lattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2, 30–32 (1963).

Gemmell, D. S. Channeling and related effects in the motion of charged particles through crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 129–227 (1974).

Nordlund, K., Djurabekova, F. & Hobler, G. Large fraction of crystal directions leads to ion channeling. Phys. Rev. B 94, 214109 (2016).

Cai, D., Gro/nbech-Jensen, N., Snell, C. M. & Beardmore, K. M. Phenomenological electronic stopping-power model for molecular dynamics and monte carlo simulation of ion implantation into silicon. Phys. Rev. B 54, 17147–17157 (1996).

Ullah, R., Corsetti, F., Sánchez-Portal, D. & Artacho, E. Electronic stopping power in a narrow band gap semiconductor from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125203 (2015).

Ziegler, J. F. SRIM-2008.04 software package. http://www.srim.org. (2008).

Nordlund, K. et al. Primary Radiation Damage in Materials: Review of Current Understanding and Proposed New Standard Displacement Damage Model to Incorporate In-cascade Mixing and Defect Production Efficiency Effects (OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, Paris, France, NEA-NSC-DOC-2015-9, 2015).

Goebl, D., Khalal-Kouache, K., Roth, D., Steinbauer, E. & Bauer, P. Energy loss of low-energy ions in transmission and backscattering experiments. Phys. Rev. A 88, 032901 (2013).

Sand, A. E., Dudarev, S. L. & Nordlund, K. High energy collision cascades in tungsten: dislocation loops structure and clustering scaling laws. EPL 103, 46003 (2013).

Sand, A. E., Aliaga, M. J., Caturla, M. J. & Nordlund, K. Surface effects and statistical laws of defects in primary radiation damage: tungsten vs. iron. Europhys. Lett. 115, 36001 (2016).

de la Rubia, T. D., Averback, R. S., Benedek, R. & King, W. E. Role of thermal spikes in energetic displacement cascades. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1930–1933 (1987).

Sand, A. E. & Nordlund, K. On the lower energy limit of electronic stopping in simulated collision cascades in Ni, Pd and Pt. J. Nucl. Mater. 456, 99–105 (2015).

Rieth, M. et al. A brief summary of the progress on the EFDA tungsten materials program. J. Nucl. Mater. 442, S173–S180 (2013).

Marian, J. et al. Recent advances in modeling and simulation of the exposure and response of tungsten to fusion energy conditions. Nucl. Fusion 57, 092008 (2017).

Zeb, M. A. et al. Electronic stopping power in gold: the role of dElectrons and theH/HeAnomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 225504 (2012).

Correa, A. A., Kohanoff, J., Artacho, E., Sánchez-Portal, D. & Caro, A. Nonadiabatic forces in ion-solid interactions: the initial stages of radiation damage. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 213201 (2012).

Zeb, M. A., Kohanoff, J., Sánchez-Portal, D. & Artacho, E. Electronic stopping power of H and He in Al and LiF from first principles. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 303, 59–61 (2013).

Mao, F., Zhang, C. & Zhang, F.-S. Theoretical study of the channeling effect in the electronic stopping power of silicon carbide nanocrystal for low-energy protons and helium ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 342, 215–220 (2015).

Lim, A. et al. Electron elevator: excitations across the band gap via a dynamical gap state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 043201 (2016).

Yost, D. C. & Kanai, Y. Electronic stopping for protons and α particles from first-principles electron dynamics: the case of silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115107 (2016).

Reeves Kyle, G. & Kanai, Y. Electronic excitation dynamics in liquid water under proton irradiation. Sci. Rep. 7, 40379 (2017).

Roth, D. et al. Electronic stopping of slow protons in transition and rare earth metals: breakdown of the free electron gas concept. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 103401 (2017).

Quashie, E. E., Saha, B. C. & Correa, A. A. Electronic band structure effects in the stopping of protons in copper. Phys. Rev. B 94, 155403 (2016).

Ojanperä, A., Krasheninnikov, A. V. & Puska, M. Electronic stopping power from first-principles calculations with account for core electron excitations and projectile ionization. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035120 (2014).

Yost, D. C., Yao, Y. & Kanai, Y. Examining real-time time-dependent density functional theory nonequilibrium simulations for the calculation of electronic stopping power. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115134 (2017).

Ullah, R., Artacho, E. & Correa, A. A. Core electrons in the electronic stopping of heavy ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 116401 (2018).

Eriksson, L., Davies, J. A. & Jespersgaard, P. Range measurements in oriented tungsten single crystals (0.1–1.0 mev). i. electronic and nuclear stopping powers. Phys. Rev. 161, 219–234 (1967).

Winterbon, K. B. Z1 oscillations in stopping of atomic particles. Can. J. Phys. 46, 2429 (1968).

Caro, M., Tamm, A., Correa, A. & Caro, A. On the local density dependence of electronic stopping of ions in solids. J.Nucl. Mater. 507, 258–266 (2018).

Nordlund, K. & Hobler, G. Dependence of ion channeling on relative atomic number in compounds. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B. 435, 61–69 (2018).

Eriksson, L. Range measurements in oriented tungsten single crystals (0.1–1.0 mev). ii. a detailed study of the channeling of k42 ions. Phys. Rev. 161, 235–244 (1967).

Nordlund, K., Runeberg, N. & Sundholm, D. Repulsive interatomic potentials calculated using Hartree-Fock and density-functional theory methods. Nucl. Instr. and Meth. B 132, 45–54 (1997).

Schleife, A., Draeger, E. W., Kanai, Y. & Correa, A. A. Plane-wave pseudopotential implementation of explicit integrators for time-dependent Kohn-Sham equations in large-scale simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 22A546 (2012).

Gygi, F. Architecture of qbox: a scalable first-principles molecular dynamics code. IBM J.Res. Dev. 52, 137–144 (2008).

Draeger, E. W. et al. Massively parallel first-principles simulation of electron dynamics in materials. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 106, 205–214 (2017).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Nazarov, V. U., Pitarke, J. M., Takada, Y., Vignale, G. & Chang, Y.-C. Including nonlocality in the exchange-correlation kernel from time-dependent current density functional theory: application to the stopping power of electron liquids. Phys. Rev. B 76, 205103 (2007).

Ashcroft, N. & Mermin, N. Solid State Phys. (Saunders College, Philadelphia, 1976).

Kleinman, L. & Bylander, D. M. Efficacious form for model pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 1425–1428 (1982).

Nordlund, K. Molecular dynamics simulation of ion ranges in the 1–100 kev energy range. Comput. Mater. Sci. 3, 448–456 (1995).

Acknowledgements

A.E.S. acknowledges support from the Academy of Finland through project no. 311472. R.U. is grateful to Emilio Artacho for his guidance and support. Work by R.U. and by A.A.C. was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract no. DE-AC52-07NA27344 with computing time awarded by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Computing Grand Challenge program. R.U. acknowledges financial support from MINECO-Spain through Plan Nacional Grant nos. FIS2012-37549 and FIS2015-64886, and Formación de Personal Investigador (FPI) PhD Fellowship Grant no. BES-2013-063728.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E.S. conceived the MD-based part of the project and the experimental comparison, carried out all of the MDRANGE simulations and analysis thereof, performed some of the TDDFT simulations, and wrote most of the paper. R.U. performed most of the TDDFT simulations and contributed to writing the paper. A.A.C. led the TDDFT work and the analysis thereof, proposed the impact parameter analysis of the MD trajectories, and contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sand, A.E., Ullah, R. & Correa, A.A. Heavy ion ranges from first-principles electron dynamics. npj Comput Mater 5, 43 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0180-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0180-5

This article is cited by

-

Empirical formula and computer code for the range of charged particles with \(Z = 2{-}103\) and \(E = 2.5{-}500\) AMeV in aluminum

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2022)