Abstract

The product Jahn–Teller effect may occur for such coupled electron–phonon systems in solids where single electrons occupy double degenerate orbitals. We propose that the excited state of the neutral XV split-vacancy complex in diamond, where X and V labels a group-IV impurity atom of X = Si, Ge, Sn, Pb and the vacancy, respectively, is such a system with eg and eu double degenerate orbitals and Eg quasi-localized phonons. We develop and apply ab initio theory to quantify the strength of electron–phonon coupling for neutral XV complexes in diamond, and find a significant impact on the corresponding optical properties of these centers. Our results show good agreement with recent experimental data on the prospective SiV(0) quantum bit, and reveals the complex nature of the excited states of neutral XV color centers in diamond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluorescent, paramagnetic point defects in diamond may realize quantum bits for quantum technology. Split-vacancy complexes of group-IV impurity atom (X = Si, Ge, Sn, Pb) and vacancy, that is, XV defects with D3d symmetry are in the focus of intense research. The negatively charged XV, that is, XV(−) defects have S = 1/2 spin state and fluoresce mostly in the visible.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 The inversion symmetry of the centers assumes virtually no Stark shift in the optical signals, which is a prerequisite for realization of indistinguishable single photon sources. Among these color centers, SiV(−) is the most studied,2,4,5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and stands out with a large Debye–Waller (DW) factor of 0.7, and the demonstration of quantum communication and sensor applications.12,13 On the other hand, the SiV(−) exhibits short spin coherence times due to phonon dephasing caused by the dynamic Jahn–Teller effect on the orbital doublet,18 thus cooling to the millikelvin regime is required for quantum bit operations.23,24 It is predicted that PbV(−) might have much longer spin coherence times because of the enlarged gap of the orbital doublet caused by spin–orbit interaction, but with the expense of smaller Debye–Waller factor than that of SiV(−).25

Alternatively, by removing an electron from XV(−) centers, an orbital singlet with S = 1 ground state appears2,26,27,28,29 that should have intrinsically long coherence times. Recently, it has been demonstrated that SiV(0) exhibits spin coherence time almost up to a second and relaxation time nearly a minute30 at 20 K together with a near-infrared fluorescence signal, and has been proposed for quantum communication applications.30 This observation naturally shifts the focus towards XV(0) color centers in diamond. However, the nature of the excited and shelving states and levels are far from being understood for SiV(0).31 In particular, the 946-nm zero-phonon-line (ZPL) optical transition of SiV(0) (see refs. 30,32,33,34,35,36) was originally assigned to an 3A2g ↔ 3A1u electronic excitation from the ground state to the excited state;5,34 however, it has been very recently revealed that the excited state should be a 3Eu state deduced from stress measurements.36 Furthermore, a dark 3A2u state below the 3Eu by 6.7 meV was activated in the luminescence spectrum by exerting uniaxial stress on the diamond sample.36 The optical signals of other XV(0) centers have not yet been identified at all. First principles methods are major tools to explore the complex physics of point defects that can strongly contribute to understanding SiV(0) color center and identifying the other XV(0) color centers.

In this article, we present first principles results on the optical properties of XV(0) color centers in diamond. We show that the electrons and phonons are strongly coupled in the electronic excited states, and they constitute of a (eg ⊗ eu) ⊗ Eg product Jahn–Teller (pJT) system, where eg and eu refers to the corresponding electronic orbitals that are simultaneously coupled to quasi-localized Eg symmetry breaking local vibrational mode. This pJT effect is responsible for the anomalous optical spectrum of SiV(0). We briefly discuss our results in the context of quantum technology applications. We provide the theoretical optical signatures of the other XV(0) color centers too.

XV(0) defect has six carbon dangling bonds and the impurity atoms sits in the inversion center of diamond (see Fig. 2c) and exhibits D3d symmetry. These six dangling bonds introduce a1g ⊕ a2u ⊕ eu ⊕ eg orbitals.2,5,14,29,34 The a1g and a2u levels fall in the valence band (VB) of the diamond.8 The eu level is fully occupied by four electrons and it either resonant with the VB or pops up in the gap by increasing the X atomic number.25 The eg level is occupied by two electrons in the band gap of diamond in the ground state. By promoting an electron from the eu orbital to the eg orbital (or forming a single hole on both orbitals), the lowest energy optically active and inactive excited states are formed. The 16 electronic configurations from these orbitals are

where we focus on the 12-dimensional triplet subspace.

The excited triplet two-hole wavefunctions and the |3A2g〉 ground state can be expressed by the following equations in the hole representation,

where we introduce the anti-symmetrization operator \({\cal A}|ab\rangle = (|ab\rangle - |ba\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) and symmetrization operator \({\cal S}|ab\rangle = (|ab\rangle + |ba\rangle )/\sqrt 2\), and spin-up (spin-down) holes are labeled by ↑ (↓). It is worth to note that two singlet levels (|1A1g〉, |1Eg〉) for the \(e_g^2\) electronic configuration appear above the |3A2g〉 ground state and below the (egeu) excited triplet levels of Eq. 1. Additionally, the (egeu) excited singlet levels are expected to lie above the (egeu) excited triplets due to the Coulomb repulsion.31,36 We show the single determinant states of the triplets in Eq. 2 in Fig. 1 in their respective Sz = +1 spin substate (see also Supplementary Note 1). We calculate these five \({\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gy}\rangle \otimes | \uparrow \uparrow \rangle\) wavefunctions by means of Kohn–Sham density functional theory (DFT) (see Methods).

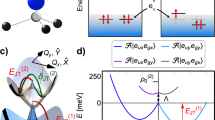

a Kohn–Sham orbitals and levels of the SiV(0) defect in its |3A2g〉 ground state and its four excited state single determinants, as obtained from ab initio density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The geometry of the system is constrained to D3d symmetry, thus these electronic configurations correspond to the undistorted X = 0 configurational coordinate in Fig. 3. The Kohn–Sham orbitals in the spin-up (spin-down) channel are represented by triangles pointing upwards (downwards). The filled (empty) triangles depict occupied (empty) orbitals. The eux, euy orbitals in the spin-down channel fall into the valence band (VB) and are smeared, so their position is very schematic. However, the eux, euy orbitals in the spin-up channel form resonant and localized states above the VB edge far from the conduction band (CB). We show the optical excitation path of the |3A2g〉 ground state by an inclined arrow pointing upwards. b Visualization of single-particle Kohn–Sham wavefunctions. The gray ball depicts the impurity atom, while the black balls depict the six first neighbor carbon atoms

Results

Formulation of the pJT Hamiltonian

Our DFT calculations indicate a strong Jahn–Teller distortion in the lowest energy triplet excited state of XV(0), going from the high D3d symmetry to the low C2h symmetry. This can be understood by considering the fact that eg and eu orbitals are occupied by a single hole in the excited state, thus they are both Jahn–Teller unstable. By applying the E ⊗ e Jahn–Teller theory on both orbitals in the strongly coupled limit and constructing an antisymmetric product \(\left( {{\cal A}|e_{ux}^\varphi e_{gx}^\varphi \rangle } \right)\) of the two particles with adding the spin degrees of freedom, one will arrive to the following (see Eqs. S23–S30),

which corresponds to walking on the yellow circle of the adiabatic potential energy surface (APES) in Fig. 2a. An accurate solution can be found by solving the following Hamiltonian,

where \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{osc}}}\) is the two-dimensional harmonic oscillator spectrum of the Eg phonon mode, \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{pJT}}}\) is the the pJT Hamiltonian, and \(\hat W\) is the electron correlation Hamiltonian between the triplet states in Eq. 2. We define \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{osc}}}\) by means of ladder operators (\(a^{\,}_{X,Y} , \, a_{X,Y}^\dagger\)) as \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{osc}}} = \hbar \omega _{\mathrm{E}}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_\alpha ^{X,Y} \left( {a_\alpha ^\dagger a_\alpha + \frac{1}{2}} \right)\), where ℏωE is the effective phonon energy.

a Adiabatic potential energy surface of SiV(0) that shows product Jahn–Teller (pJT) effect in the excited state. We show the vertical absorption and luminescence with blue and red arrows, respectively, while the black arrow denotes the zero-phonon-line (ZPL) transition. We label the polaronic solutions by tilde in the excited state with energy gap of 6.7 meV. b Triplet states of SiV(0). c Geometry of the undistorted SiV(0) defect with D3d symmetry. We also depict the X and Y distortion paths of the Eg phonon mode that are quasi-localized on the six carbon atoms

The usual e ⊗ E linear Jahn–Teller Hamiltonian37,38,39,40 is modified to

where u/g labels the eu/eg orbital, and σz and σx are the standard Pauli matrices in Eq. 5. \(\hat \sigma _0\) is the two-dimensional unit matrix that is introduced for the individual electron–phonon coupling strength Fu and Fg.41 \((\hat X,\hat Y) = (a_{(X,Y)}^\dagger + a_{(X,Y)})/\sqrt 2\) defines the two-dimensional configuration space spanned by the Eg vibration mode through the harmonic oscillator ladder operators. See Supplementary Note 3 for details about the derivation of Eq. 5. Finally, we define the position of electronic levels by Λ and Ξ caused by static electronic correlation with the following expression (see Supplementary Note 2):

The overall Hamiltonian of the system in a 4 × 4 matrix notation is the following by combining Eqs. 2–6:

where we label the individual single determinant electronic wavefunctions at \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{pJT}}}\) for clarity (see also Supplementary Note 3). The diagonal part of the pJT matrix is self-explanatory. If the geometry is distorted towards +X, the |euxegx〉 wavefunction would lower its energy, by a joint Fu + Fg coupling strength. In the central part of diagonal Hamiltonian, the two Jahn–Teller effects are destructive, and the joint product Jahn–Teller strength is Fu − Fg.

Next, the parameters in Eq. 7 are determined by first principles DFT calculations, and the coupled electron–phonon Hamiltonian is solved (see Supplementary Note 3 for details).

Parameters from ab initio calculations

We show the ab initio parametrization of the full Hamiltonian for SiV(0), and discuss the results in detail. The key results are also summarized for the other XV(0) color centers in Table 1 as obtained by the same procedure. Our DFT ΔSCF method yields the total energy of the four, \({\cal A}|e_{uy}e_{gy}\rangle\), \({\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gy}\rangle\), \({\cal A}|e_{uy}e_{gx}\rangle\), and \({\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gx}\rangle\), electronic configurations (see also Supplementary Note 3 and Fig. S2). The APES of these states is depicted in Fig. 3a. This is our starting point to determine the parameters in Eq. 7.

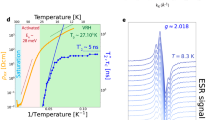

a Ab initio adiabatic potential energy surface (APES) as obtained from Kohn–Sham DFT for SiV(0), where mc refers to reduced mass of the vibration. The X = 0 point refers to the geometry relaxation in the constraint of D3d symmetry. The global minimum in APES is obtained upon releasing all symmetry constraints that yields \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(1)}\) JT energy. We mapped the APES with linear interpolation between these two geometries. We mirrored the X > 0 results to X < 0 regions. We determined the \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(2)}\) energy by fitting quadratic polynomials on the data points. b Geometry dependence of eigenvalues of Eq. 7 by using X as continuous variable and Y = 0 where the configuration coordinate is in dimensionless unit. We label the wavefunction character with colored balls. Red (teal) balls correspond to the pure |3A1u〉 (|3Eux〉 or |3Euy〉) character that are optically active states. Black balls correspond to the pure |3A2u〉 character that is dark state. See Supplementary Note 3 for the four layers in the APES. c The convergent polaronic eigenstates of Eq. 7 with color-coded electronic characters and expectation value of the distortion (R) from the D3d symmetry in dimensionless unit. We show the lowest energy vibronic solutions and δ energy gap between them by yellow balls

In D3d symmetry, \(E_{{\mathrm{tot}}}[{\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gy}\rangle ] = E_{{\mathrm{tot}}}[{\cal A}|e_{uy}e_{gx}\rangle ]\) and \(E_{{\mathrm{tot}}}[{\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gx}\rangle ] = E_{{\mathrm{tot}}}[{\cal A}|e_{uy}e_{gy}\rangle ]\), where Etot is the DFT total energy (see Supplementary Note 2). Finally, the calculated energy separation is Λ = 78.3 meV for SiV(0).

We determine the position of |3Eu〉 by a \(|e_{u \pm }\rangle = (|e_{ux}\rangle \pm i|e_{uy}\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) transformation on the defect orbitals, thus two-hole wavefunction will be a single determinant in this basis as \(|\,{}^3E_u\rangle = {\cal A}|e_{u \pm }e_{u \pm }\rangle\), which can be directly approximated by means of DFT (see Supplementary Note 2). Finally, Ξ = 44.9 meV is obtained by this procedure for SiV(0).

The effective vibration energy ℏωE can be found by fitting to the parabola of the lowest APES curvature in Fig. 3a that results in 75.9 meV for SiV(0).

The electron–phonon coupling Fg and Fu parameters can be derived by reading out the characteristic Jahn–Teller energies \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(1)}\) and \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(2)}\) in the APES (see Fig. 3a) as follows:

In SiV(0), \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(1)} = 258\,{\mathrm{meV}}\), that is very significant and seriously affect the calculated ZPL energy. On the other hand, \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(1)} = 0.47\,{\mathrm{meV}}\), which is small, and results nearly identical to Fg and Fu. We note here that we neglect the quadratic Jahn–Teller terms in Eq. 5, that is, the APES in Fig. 3 is axially symmetric. However, the \({\cal A}|e_{uy}e_{gy}\rangle\) has a bit smaller Jahn–Teller energy than that of \({\cal A}|e_{ux}e_{gx}\rangle\) by 43, 46, 46, and 48 meV for SiV, GeV, SnV, and PbV, respectively, that would cause a quadratic Jahn–Teller effect. However, these energies are an order of magnitude smaller than that of \(E_{{\mathrm{JT}}}^{(1)}\), and would only lead to minor correction to the results from linear Jahn–Teller approximation. We explicitly proved this for XV(−) color centers in our previous study.25 Therefore, we still apply the linear Jahn–Teller approximation for the sake of simplicity.

Finally, all the parameters could be derived or read out from the calculated APES (see Table 1), thus one can setup the full Hamiltonian in Eq. 7. It is intriguing to use X as a continuous variable at Y = 0 in Eq. 7, and plot the solution in Fig. 3b. The contribution of the dark 3A2u state is shown by black balls, while the contribution of the optically active 3A1u state (z polarization) and 3Eu state [(x,y) polarization] is depicted as red and teal balls, respectively. The lowest energy solution will apparently involve the dark 3A2u state. For the full quantum mechanical solution (where X and Y are operators), we use the following wavefunction ansatz:25,42,43

where |n, m〉 is the representation of Eg vibration that we consider up to 15-quanta limit (n + m ≤ 15) for the low energy spectrum and up to 50-quanta limit for high energies in Fig. 3c as explained in Supplementary Note 3. The vibronic spectrum shows up two deep levels that are separated by δ = 6.8 meV, where the deepest level belongs to the vibronic \(|\,{}^3\tilde A_{2u}\rangle\) and the second level is associated with the vibronic \(|\,{}^3\tilde E_u\rangle\) in SiV(0).

We also show the derived parameters and results for GeV, SnV, and PbV systems in Table 1. There is a clear trend that the ZPL energies increase with heavier impurity atom.

On the other hand, the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) will be significant for heavy impurity atoms, and rapidly increase with the atomic number of the impurity atom. Based on our previous calculations for XV(−) defects,25 the SOC on |eu〉 orbitals, λu is 7, 33, 100, and 250 meV for SiV, GeV, SnV, and PbV, respectively. This can be neglected for SiV(0) but can be significant for the other XV(0) defects, that might alter the ZPL energies SnV(0) and PbV(0). The simultaneous solution for pJT and SOC is out of the scope of this paper but might be required for the ultimately accurate description of the excited states of SnV(0) and PbV(0).

Discussion

Experimental data are only available for SiV(0), thus we can directly compare our results only to them. A recent stress measurement on the photoluminescence spectrum of SiV(0) revealed a dark state where the corresponding level was below the ZPL energy by 6.8 meV.36 Our calculations explain this feature by the pJT effect of the three triplet excited states. The lowest energy branch of the excited state triplets yield ≈50% |3A2u〉 and ≈50% |3Eu〉 electronic character that can be anticipated from Eq. 3. The lowest energy vibronic state is the dark \(|\,{}^3\tilde A_{2u}\rangle\) (951 nm), and the next vibronic level above it by 6.7 meV belongs to the optically allowed \(|\,{}^3\tilde E_u\rangle\) (ZPL of 946 nm). We note that in ordinary e ⊗ E JT systems, a degenerate E level is the lowest vibronic state quickly followed by a nondegenrate A vibronic level by tunneling splitting energy.37,38,44,45,46 In our present pJT case, the order of these states are reversed, which is a clear signature of the manifestation of the pJT effect.

There are numerous consequences of this finding: (i) The optical polarization of the emitted photons at the ZPL (946 nm) is perpendicular to the symmetry of the axis. (ii) The emission will be strain dependent as the symmetry breaking strain can activate the 951-nm ZPL transition, again with photon polarization perpendicular to the symmetry axis of the defect. (iii) The 946-nm ZPL intensity will be temperature dependent, as it depends on the thermal occupation of the \(|\,{}^3\tilde E_u\rangle\) over the lowest energy \(|\,{}^3\tilde A_{2u}\rangle\). These properties were indeed observed in previous experiments.34,36

We developed a theory for the excited state of XV(0) quantum bits in diamond, which revealed a pJT effect, that is, strong coupling of a localized vibration mode to multiple triplet electronic states. We showed that our theory can explain numerous experimental features of SiV(0) color center. We predicted the basic optical properties of the other XV(0) color centers too. Our results provide tools to experimentally test pJT systems in solid state. Our findings can be useful to guide experiments on these color centers for quantum bit applications.

Methods

Numerical solution of the Jahn–Teller Hamiltonian

We determined the energy levels of the product Jahn–Teller system (Eq. 7) by a numerical code implemented in GNU octave that we describe in the Supplementary Information.

DFT calculations

We characterized XV(0) color centers by plane wave supercell calculations within spin-polarized DFT as implemented in the vasp 5.4.1 code.47 We determined the electronic structure within the Born–Oppenheimer approximation where the ions are treated as classical particles and where the minimum energy is found by moving the atoms until the quantum mechanical forces acting on the ions fall below 10−3 eV/Å. We embedded the XV(0) defects in a 512-atom diamond supercell. The Brillouin zone is sampled at the Γ-point. We applied an energy cutoff at 370 eV for expressing the plane wave basis set within the applied projector augmentation wave method.48,49 We calculated the excited states with the constrained-occupation DFT method (ΔSCF method).50 We used the HSE06 hybrid functional51,52 that reproduces the experimental band gap and the charge transition levels in Group-IV semiconductors within 0.1 eV accuracy.53 For the electron–phonon coupling calculations of XV(0) defects, we applied the same machinery that could well reproduce the ZPL energies of XV(−) exhibiting the dynamic Jahn–Teller effect;25 thus, we expect similar performance for XV(0) too.

Data availability

The data from DFT calculations that support the findings of this study are available from Gergő Thiering (email: thiering.gergo@wigner.mta.hu) upon reasonable request.

References

Zaitsev, A., Vavilov, V. & Gippius, A. Cathodoluminescence of diamond associated with silicon impurity. Sov. Phys. Lab. Inst. Rep. 10, 15–17 (1981).

Goss, J. P., Jones, R., Breuer, S. J., Briddon, P. R. & Öberg, S. The twelve-line 1.682 ev luminescence center in diamond and the vacancy-silicon complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3041–3044 (1996).

Clark, C. D., Kanda, H., Kiflawi, I. & Sittas, G. Silicon defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 51, 16681–16688 (1995).

Neu, E. et al. Single photon emission from silicon-vacancy colour centres in chemical vapour deposition nano-diamonds on iridium. N. J. Phys. 13, 025012 (2011).

Gali, A. & Maze, J. R. Ab initio study of the split silicon-vacancy defect in diamond: electronic structure and related properties. Phys. Rev. B 88, 235205 (2013).

Iwasaki, T. et al. Germanium-vacancy single color centers in diamond. Scientific Rep. 5, 12882 (2015).

Ralchenko, V. G. et al. Observation of the ge-vacancy color center in microcrystalline diamond films. Bull. Lebedev Phys. Inst. 42, 165–168 (2015).

Häußler, S. et al. Photoluminescence excitation spectroscopy of SiV- and GeV-color center in diamond. N. J. Phys. 19, 063036 (2017).

Tchernij, S. D. et al. Single-photon-emitting optical centers in diamond fabricated upon sn implantation. ACS Photonics 4, 2580–2586 (2017).

Iwasaki, T. et al. Tin-vacancy quantum emitters in diamond. arXiv preprint at http://arXiv.org/1708.03576 (2017).

Trusheim, M. E. et al. Lead-related quantum emitters in diamond. In Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, FTu4H.2 (Optical Society of America, 2018). https://www.osapublishing.org/abstract.cfm?uri=CLEO_QELS-2018-FTu4H.2.

Sipahigil, A. et al. An integrated diamond nanophotonics platform for quantum-optical networks. Science 354, 847–850 (2016).

Kucsko, G. et al. Nanometre-scale thermometry in a living cell. Nature 500, 54–58 (2013).

Hepp, C. et al. Electronic structure of the silicon vacancy color center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 036405 (2014).

Müller, T. et al. Optical signatures of silicon-vacancy spins in diamond. Nat. Commun. 5, 3328 (2014).

Rogers, L. J. et al. All-optical initialization, readout, and coherent preparation of single silicon-vacancy spins in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 263602 (2014).

Rogers, L. J. et al. Electronic structure of the negatively charged silicon-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 89, 235101 (2014).

Jahnke, K. D. et al. Electron–phonon processes of the silicon-vacancy centre in diamond. N. J. Phys. 17, 043011 (2015).

Neu, E. et al. Low-temperature investigations of single silicon vacancy colour centres in diamond. N. J. Phys. 15, 043005 (2013).

Riedrich-Möller, J. et al. Deterministic coupling of a single silicon-vacancy color center to a photonic crystal cavity in diamond. Nano Lett. 14, 5281–5287 (2014).

Pingault, B. et al. All-optical formation of coherent dark states of silicon-vacancy spins in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 263601 (2014).

Dietrich, A. et al. Isotopically varying spectral features of silicon-vacancy in diamond. N. J. Phys. 16, 113019 (2014).

Becker, J. N. et al. All-optical control of the silicon-vacancy spin in diamond at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 053603 (2018).

Sukachev, D. et al. Silicon-vacancy spin qubit in diamond: a quantum memory exceeding 10 ms with single shot state readout. Phys. Rev. Lett 119, 223602 (2017).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio magneto-optical spectrum of group-IV vacancy color centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021063 (2018).

Iakoubovskii, K. & Stesmans, A. Characterization of defects in as-grown CVD diamond films and HPHT diamond powders by electron paramagnetic resonance. Phys. Stat. Sol. A 186, 199–206 (2001).

Edmonds, A. M., Newton, M. E., Martineau, P. M., Twitchen, D. J. & Williams, S. D. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of silicon-related defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 77, 245205 (2008).

Goss, J. P., Briddon, P. R., Rayson, M. J., Sque, S. J. & Jones, R. Vacancy-impurity complexes and limitations for implantation doping of diamond. Phys. Rev. B 72, 035214 (2005).

Goss, J. P., Briddon, P. R. & Shaw, M. J. Density functional simulations of silicon-containing point defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 76, 075204 (2007).

Rose, B. C. et al. Observation of an environmentally insensitive solid-state spin defect in diamond. Science 361, 60–63 (2018).

Rose, B. C. et al. Strongly anisotropic spin relaxation in the neutral silicon vacancy center in diamond. arXiv preprint at http://arXiv.org/1710.03196 (2017).

Allers, L. & Collins, A. T. Photoconductive spectroscopy of diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 77, 3879–3884 (1995).

Breeding, C. M. & Wang, W. Occurrence of the Si–V defect center in natural colorless gem diamonds. Diam. Relat. Mater. 17, 1335–1344 (2008).

Green, B. et al. Electronic structure of the neutral silicon-vacancy center in diamond. arXiv preprint at http://arXiv.org/1804.09141 (2018).

D’Haenens-Johansson, U. F. S. et al. Optical properties of the neutral silicon split-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 84, 245208 (2011).

Green, B. et al. Neutral silicon-vacancy center in diamond: spin polarization and lifetimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 096402 (2017).

Bersuker, I. The Jahn–Teller Effect (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Bersuker, I. & Polinger, V. Vibronic Interactions in Molecules and Crystals, Vol. 49 (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, 2012).

Ham, F. S. Effect of linear Jahn–Teller coupling on paramagnetic resonance in a 2 E state. Phys. Rev. 166, 307–321 (1968).

Ham, F. S. Dynamical Jahn–Teller effect in paramagnetic resonance spectra: orbital reduction factors and partial quenching of spin-orbit interaction. Phys. Rev. 138, A1727–A1740 (1965).

Qiu, Q. C. & Ceulemans, A. The {E ⊗ E} ⊗ e Vibronic Coupling Case: A Prototypal Product Jahn-Teller System. Kaplan M.D., Zimmerman G.O. (Eds) In Vibronic Interactions: Jahn–Teller Effect in Crystals and Molecules. NATO Science Series (Series II: Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry), Vol. 39. (Springer, Dordrecht, 2001).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio calculation of spin–orbit coupling for an nv center in diamond exhibiting dynamic Jahn–Teller effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081115 (2017).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Theory of the optical spin-polarization loop of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085207 (2018).

Bersuker, I. Inversion splitting of levels in free complexes of transition metals. Sov. Phys. JETP 16, 4 (1963).

Reynolds, R. W. & Boatner, L. A. Dynamic, intermediate, and static Jahn–Teller effect in the EPR spectra of E2 orbital states. Phys. Rev. B 12, 4735–4754 (1975).

García-Fernández, P., Trueba, A., Barriuso, M. T., Aramburu, J. A. & Moreno, M. Tunneling splitting of Jahn–Teller ions in oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 035901 (2010).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Bengone, O., Alouani, M., Blöchl, P. & Hugel, J. Implementation of the projector augmented-wave LDA + U method: application to the electronic structure of NiO. Phys. Rev. B 62, 16392–16401 (2000).

Gali, A. Identification of individual 13C isotopes of nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond by combining the polarization studies of nuclear spins and first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 80, 241204 (2009).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Krukau, A. V., Vydrov, O. A., Izmaylov, A. F. & Scuseria, G. E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 224106 (2006).

Deák, P., Aradi, B., Frauenheim, T., Janzén, E. & Gali, A. Accurate defect levels obtained from the hse06 range-separated hybrid functional. Phys. Rev. B 81, 153203 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Support from ÚNKP-17-3-III New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities of Hungary, the National Research Development and Innovation Office of Hungary within the Quantum Technology National Excellence Program (Project Contract No. 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00001), and the European Commission of H2020 ASTERIQS project (Grant No. 820394) is acknowledged. We thank the National Information Infrastructure Development Program for the high-performance computing resources in Hungary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.T. performed the simulations and analyzed the data. A.G. conceived the research and wrote the manuscript with G.T. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thiering, G., Gali, A. The (eg ⊗ eu) ⊗ Eg product Jahn–Teller effect in the neutral group-IV vacancy quantum bits in diamond. npj Comput Mater 5, 18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0158-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0158-3

This article is cited by

-

Coherence of a charge stabilised tin-vacancy spin in diamond

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Strong spin–orbit quenching via the product Jahn–Teller effect in neutral group IV qubits in diamond

npj Quantum Materials (2020)

-

Quantum simulations of materials on near-term quantum computers

npj Computational Materials (2020)