Abstract

Ruthenium dioxide is presently the most active catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in acidic media but suffers from severe Ru dissolution resulting from the high covalency of Ru-O bonds triggering lattice oxygen oxidation. Here, we report an interstitial silicon-doping strategy to stabilize the highly active Ru sites of RuO2 while suppressing lattice oxygen oxidation. The representative Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst exhibits high activity and stability in acid with a negligible degradation rate of ~52 μV h−1 in an 800 h test and an overpotential of 226 mV at 10 mA cm−2. Differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) results demonstrate that the lattice oxygen oxidation pathway of the Si-RuO2−0.1 was suppressed by ∼95% compared to that of commercial RuO2, which is highly responsible for the extraordinary stability. This work supplied a unique mentality to guide future developments on Ru-based oxide catalysts’ stability in an acidic environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The proton-exchange membrane water electrolyzer (PEMWE) is regarded as one of the most efficient devices for green hydrogen production because of its small footprint, high current density, and fast response1,2,3,4. However, the instability of anode catalysts has extremely hindered the large-scale application of PEMWE devices5,6,7. Despite the IrO2 catalyst with the passable stability applied in commercial PEMWE, its unsatisfactory activity asks for a high loading in the anode, sharply raising the cost of PEMWE8,9,10,11,12. Fortunately, ruthenium dioxide (RuO2), with low price and high intrinsic activity, is expected to be the ideal alternative to IrO2 after extricating from poor stability13,14,15. Encouragingly, the previously reported works have revealed its degradation mechanism. The high covalency of Ru-O bonds triggers the lattice oxygen oxidation mechanism (LOM), leading to oxygen vacancy (OV) formation and the leaching of active Ru species (soluble RuO4 species), which ultimately accelerates collapse of the crystal structure (Fig. 1)16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Crystal structure model of RuO2 (top-left corner) and Si-RuO2 (bottom-left corner). The illustration of LOM pathway of RuO2 (middle top) and AEM pathway of Si-RuO2 (middle top) due to differences in their covalency, in which O labeled in red represents lattice oxygen and O labeled in green represents oxygen from water. Schematic of the structural changes in RuO2 (top-right corner) and Si-RuO2 (bottom-right corner) under acidic OER conditions.

Inspired by the theoretical results, doping heterogeneous metal atoms in RuO2 has been presented and has effectively modified the Ru-O bond covalency18,23. Nevertheless, most doping elements, such as Co24, Na25, Mn15, Cr26, Cu27 and Ni28, enhance Ru-O bond covalency while activating the LOM pathway, resulting in improved activity but poor stability. Very few elements have been reported and used to weaken Ru-O bond covalency and improve the stability of Ru-based oxides. Zhang’s group18 reported that W and Er co-doping increased the formation energy of OV in RuO2 and prohibited lattice oxygen oxidation by downshifting the O 2p band center away from the Fermi level, eventually enhancing the stability of the doped-RuO2. Ge and coworkers29 investigated the effect of the doping element electronegativity on Ru-based oxides’ electron structure and performance. The prepared SnRuOx with appropriate Ru-O bond covalency followed the adsorption evolution mechanism (AEM) in the OER and exhibited orders of magnitude lifespan extension compared to that of RuO2. Although the above strategies improved the RuO2 stability somewhat, the doped metal elements are easily subjected to accelerated corrosion in harsh acidic and oxidative environments due to their thermodynamic instability30,31. Furthermore, the etched oxide without the doping metals left amorphous RuO2 on the catalyst surface and inevitably started the LOM pathway30,31,32. More importantly, the abovementioned doped Ru-based oxides are achieved by replacing the Ru atoms with doping atoms, which, however, limits the quantity of Ru-O structures in the catalyst and is not beneficial for further improving the activity of Ru-based oxides. Therefore, exploring effective doping strategies for weakening the Ru-O bond covalency without losing the quantity of Ru-O structure is extraordinarily desirable but challenging.

Here, we reveal that metalloid silicon, with superior acid resistance and short effective ion radius (EIR, 0.26 Å for Si4+ compared to 0.62 Å for Ru4+)33, is able to be inserted into the interstitial-site of the RuO2 lattice to construct stable RuO2 for the acidic OER. The stability of interstitial Si-doped RuO2 originates from the higher bond dissociation energy of the Si-O bond (798 kJ mol−1) compared to that of the Ru-O bond (481 kJ mol−1)33, which decreases the Ru-O bond covalency and is beneficial for suppressing the LOM pathway and strengthening the AEM pathway (Fig. 1). Moreover, the robust Si-O bond can prevent lattice oxygen from participating in the OER and thus prohibit OV formation. These two factors, in combination with the stability of Si in acidic media, are responsible for the high catalytic stability of the interstitial Si-doped RuO2 catalyst. As a result, a representative Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst was observed to be stable for at least 800 h with a negligible degradation rate of ~52 μV h−1 at 10 mA cm−2 in acidic electrolyte, outperforming most of the reported Ru-based oxide catalysts (Supplementary Table 4).

Results and discussions

Synthesis and characterization of Si-doped RuO2 catalysts

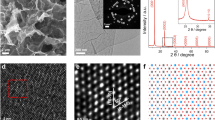

A simple and fast cation-exchange resin (CER) pyrolysis approach was applied to prepare Si-doped RuO2 catalysts with various doping levels (denoted Si-RuO2-x, where x represents the molar ratio of Si to Ru; x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of all the prepared samples matched well with that of rutile-phase RuO2 (ICSD: 43-1027), demonstrating that the incorporation of Si into the RuO2 lattice did not change the tetragonal phase structure of RuO2 (Fig. 2a). A magnification of the (110) diffraction plane (Fig. 2b), showed that the corresponding diffraction peak gradually shifted toward a lower angle as the Si content increased from 0 to 0.1 and then remained almost unchanged as the Si content further increased from 0.1–0.3. Considering that both the EIR of Si4+ and its coordination number (CN) with oxygen in nature (EIR = 0.26 Å, CN = 4) were much lower than those of Ru4+ (EIR = 0.62 Å, CN = 6), we inferred that Si tends to interstitially insert into the RuO2 lattice rather than replace the Ru atoms33,34,35,36,37. To visually prove that Si was inserted into the RuO2 interstice, spherical aberration–corrected HAADF-STEM measurements were performed. As shown in Fig. 2c, the lattice fringes with interplanar spacings of 0.318 nm and 0.254 nm were assigned to the (110) and (101) planes of rutile RuO2, respectively. Furthermore, some isolated Si atoms with low imaging contrast, which is characteristic of light elements with lower atomic numbers, were also observed in the lattice interstices of RuO2 (Fig. 2d-e). This assertion was confirmed by atomic line profiles analysis (Fig. 2f-i). Based on the above analysis, we undoubtedly concluded that Si inserts into the RuO2 interstice.

a XRD patterns of all Si-RuO2-x samples. b Magnified image of the (110) diffraction peaks of Si-RuO2-x. c HAADF-STEM image of Si-RuO2−0.1. d, e Magnified HAADF-STEM image obtained from the area highlighted with purple and green in Fig. 1c. f–i Line-scanning intensity profile obtained from the area highlighted with red lines in (e, f).

The morphology and elemental distribution of different Si-RuO2-x catalysts were further investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping. As displayed in Supplementary Figs. 1a, b–5a, b, the TEM images of all Si-RuO2-x catalysts presented a typical porous structure composed of nanoparticles with an average diameter of 5-6 nm. The formation of such a structure could be explained by the CER acting as a skeleton structure to prevent catalyst agglomeration and as a soft template for pore formation during the annealing process38. The high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) images showed that the lattice fringe spacings of the (110) and (101) planes were not significantly different among these catalysts (Supplementary Figs. 1c–5c), further confirming that after Si intercalation, the original morphology and rutile structure of RuO2 were still preserved. The corresponding EDS mapping showed that Si, Ru and O were uniformly distributed throughout the entire catalyst at the low Si doping levels of Si-RuO2−0.05, Si-RuO2−0.1 and Si-RuO2−0.2 (Supplementary Figs. 2d–4d). However, when the Si content increased to 0.3, some Si and O atoms were highly concentrated in the interior of the sample, indicating that some Si atoms did not enter the RuO2 interstice and instead formed insulating SiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Combined with the XRD results, it was inferred that the ideal doping level of Si in RuO2 interstices was around 10%.

The influence of doped Si on the electronic properties of Ru and O was investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As presented in the Si 2p spectra in Fig. 3a, the Si-RuO2−0.05 and Si-RuO2−0.1 samples presented only one prominent peak at 102.4 eV, which was attributed to the Si-O bond associated with interstitial Si. When the Si content increased to 0.2 and 0.3, an additional peak at 104.1 eV consistent with the Si-O bond in the SiO2 phase appeared. This result confirmed that the actual Si solubility in the RuO2 lattice was limited to around 10% and that the extra amount of Si preferentially formed an amorphous SiO2 phase, which agrees with the XRD and EDS results. In addition to considering the Si 2p spectra, we also analyzed the O 1 s and Ru 3p spectra (Fig. 3b, c). The peak of lattice oxygen positively shifted toward a higher binding energy with increasing Si content, while that of Ru shifted toward a lower binding energy (x ≤ 0.1) and then remained almost unchanged (0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.3). The positive shift of the O 1 s binding energy and negative shift of the Ru 3p binding energy provided direct evidence for the weakening of the Ru-O bond covalency by the incorporation of Si into the RuO2 interstices39,40,41.

The valence state and coordination environment of Ru in the representative Si-RuO2−0.1 sample were further revealed by X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) analysis. The Ru K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra showed that the absorption edge of Si-RuO2−0.1 was slightly negatively shifted compared to that of commercial RuO2 (Com-RuO2) (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating that Si-RuO2−0.1 had a lower Ru valence state than Com-RuO2. The corresponding Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra of Si-RuO2−0.1 and Com-RuO2 showed that the predominant peak of the Ru-O scattering path appeared at 1.54 Å for Si-RuO2−0.1, and this peak was slightly contracted to 1.52 Å in Com-RuO2 (Fig. 3e), suggesting that the Si tuned to Ru-O bond length. This phenomenon was also observed when comparing the Ru-Ru scattering paths in Si-RuO2−0.1 and Com-RuO2 (Fig. 3e). To more specific, the FT-EXAFS spectra were reasonably fitted (Supplementary Fig. 7). The best-fit results confirmed that Si doping led to the elongation of the Ru-O bond from 1.96 Å to 1.98 Å (Supplementary Table 1). The lower Ru valence state and elongated Ru-O bonds further proved that the Ru-O bond covalency was weakened by introducing Si into RuO2 interstices42,43,44. To further verify this conclusion, the partial density of states (PDOS) calculations on the (110) facet and bulk of RuO2 and Si-RuO2 model (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 8-9 and Supplementary Table 2) were performed, respectively. As interpreted in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 10a, after introducing Si into the interstitial sites, the surface Ru 4d band center (ɛd) upshifted from −1.759 eV – −1.626 eV, while the surface O 2p band center (ɛp) downshifted from −3.365 eV – −3.850 eV, suggesting that the gap between ɛd and ɛp was obviously enlarged. Besides, the corresponding calculated this gap for RuO2 bulk and Si-RuO2 bulk were 1.409 eV and 1.844 eV (Supplementary Fig. 10b). All results indicated that the covalency of Ru-O bond in Si-RuO2 was lower than that of RuO2. It is generally agreed that weak metal–oxygen covalency can promote the stability of catalysts by suppressing the LOM pathway during the OER20,45,46,47.

OER performance measurement and the origin of the enhanced activity

To explore the influence of the Si content on the OER activity, we recorded the polarization curves of as-prepared Si-RuO2-x and Com-RuO2 in an O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 solution. As shown in Fig. 4a-b, the Si-RuO2−0 sample without Si exhibited an overpotential of 248 mV at 10 mA cm−2, which was superior to that of Com-RuO2 (291 mV). This improved OER activity was attributed to the porous structure and smaller nanoparticles providing more active sites for the OER. With increasing Si content, the overpotential gradually decreased and reached a minimum of 226 mV for Si-RuO2−0.1; however, this minimum value increased to 234 mV for Si-RuO2−0.2 and 238 mV for Si-RuO2−0.3. To gain insight into the causes of this activity trend, we analyzed the Tafel slope and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of these catalysts to evaluate their reaction kinetics and charge-transfer ability. As displayed in Fig. 4c, the Tafel slope of Si-RuO2−0.1 was 33.0 mV dec−1, which was smaller than that of the other catalysts, indicating that Si-RuO2−0.1 had the fastest reaction kinetics. The EIS plots in Fig. 4d show that Si-RuO2−0.1 had the smallest semicircle radius among these fabricated samples, indicating that the charge-transfer resistance between the Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst and reactants was the smallest. These results suggested that incorporating an appropriate Si content (x ≤ 0.1) into the RuO2 matrix effectively enhanced the reaction rate and charge transfer, thus enhancing the intrinsic activity. However, an excessive Si content (x > 0.1) resulted in the formation of an insulating SiO2 phase that blocked the charge transfer across the grains and covered the catalytic active sites of RuO234,48,49.

a Polarization curves of Si-RuO2-x and Com-RuO2 (with a loading of 0.30 mgcat cm−2). b Overpotential at 10 mA cm−2geo of different catalysts from (a). c Corresponding Tafel slopes calculated from (a). d EIS plots of different catalysts. The high-frequency region of Nyquist plot is used to determine the solution resistance (about 30 Ω) for iR-correction. e The four electrons mechanism of OER in acidic solution. f Calculated energy barrier diagrams of Si-RuO2 and RuO2.

To comprehensively understand the origin of the enhanced acidic OER performance of the Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst, we carried out DFT calculations to investigate the change in the Gibbs free energy of the reaction intermediates based on the four elementary steps in OER process (Fig. 4e). As presented in Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 3, the formation of *OOH intermediates were the rate-determining step (RDS) for RuO2 and Si-RuO2, which is in good agreement with previous reports19,26,50,51. When the input potential was 0 V, the free energy barrier for RuO2 is 2.028 eV, and the corresponding limiting overpotential is 0.798 V, which agrees well with previous calculations14,18,26,27. However, compared with RuO2, Si-RuO2 exhibited a lower free energy barrier (1.868 eV) and overpotential (0.638 V). These results revealed that incorporating Si into RuO2 interstices plays a critical role for boosting OER activity.

Catalytic stability evaluation

Apart from activity, stability is another major concern for evaluating the industrial application of electrocatalysts52,53. As presented in Fig. 5a, the synthesized Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2 catalysts only ran for 40 h and 18 h at 10 mA cm−2, respectively, and then rose sharply to 2.5 V. In stark contrast, the Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst was active for a record 800 h with only a 42 mV increase in overpotential (Fig. 5a). The calculated degradation rate was ~52 μV h−1, outperforming most of the reported Ru-based oxide catalysts in acidic media (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 4). An inductively coupled plasma‒mass spectrometry (ICP‒MS) experiment was performed to monitor the Ru ion dissolution amount in the electrolyte during the OER process. As shown in Fig. 5c, the amount of dissolved Ru ions observed for Si-RuO2−0 was far greater than that observed for Com-RuO2, although Si-RuO2−0 remained active for a longer time. The severe leaching of Ru observed for Si-RuO2−0 was attributed to its larger surface area, which resulted in more exposed Ru sites on the reaction interface. However, with the introduction of Si, the dissolution amount and rate of Ru ions significantly decreased, suggesting that Si played an important role in inhibiting Ru ion dissolution. The so-called stability number (S-number) was calculated based on the amounts of dissolved Ru ions and generated O2 to assess the stability of the catalysts6,54. Note that for each sampling time point, the S-number of the Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst was the largest and increased with the reaction time (Supplementary Fig. 12). The S-number of the Si-RuO2−0.1 catalyst after the 13 h OER test was 3.42 × 104, which was 8.7-fold and 2.5-fold that of Si-RuO2−0 (3.95 × 103) and Com-RuO2 (1.39 × 104), respectively. These results indicated that the incorporation of Si into RuO2 interstices enhanced the stability of RuO2 toward the acidic OER.

a Chronopotentiometry stability curves of Si-RuO2−0.1 and the control samples at 10 mA cm−2. The stability curves are collected with a catalyst loading of 1.5 mgcat cm−2. The solution resistance is ~4.6 Ω in this stability test system. b Comparison of the stability and degradation rate of the Ru-based oxide catalyst at 10 mA cm−2 with that of recently reported catalysts in acidic solution. c Comparison of the amounts of leached Ru ions during the OER process observed for Si-RuO2−0.1, Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2.

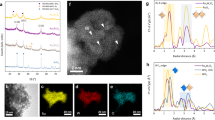

Characterization of Si-RuO2−0.1 after acidic OER

Furthermore, a series of characterizations, including XRD, TEM and XPS, were performed for the spent Si-RuO2−0.1 catalysts to investigate the structural evolution of Si-RuO2−0.1. Obviously, the crystalline structure and morphology of Si-RuO2−0.1 still maintained its integrity after the 800 h stability test (Fig. 6a-b and Supplementary Fig. 13). Meanwhile, the Si, Ru and O elements were also uniformly distributed in Si-RuO2−0.1, further illustrating the good stability of Si-RuO2−0.1 toward acidic OER (Fig. 6c). To prove that the introduction of Si highly improved dissolution and oxidation resistance of RuO2 toward the acidic OER, the chemical state changes for Ru and O in Si-RuO2−0.1 before and after the 24 h stability test were further investigated and compared with those of Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2 (Caution: The spent Com-RuO2 sample was only tested for 18 h). For the Ru 3p spectra of Si-RuO2−0.1, the Ru>+4/ Ru+4 value increased from 0.34 – 0.39 after the stability test, indicating the inevitable oxidation of catalysts under a high anode potential9,55. Despite this, for the Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2 samples, the change in the Ru>+4/ Ru+4 value is more significant, increasing from 0.43 – 0.58 and from 0.38 to 0.49, respectively (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 14). This result revealed that the introduced Si kept the Ru from overoxidation during the OER. Likewise, the evolution of oxygen species is also revealed by combining O 1 s spectra before and after the stability test. As displayed in Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 15, the remarkable increase in OV/OL value for Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2 suggests that the lattice O is involved in O2 generation to a large extent, which will accelerate the dissolution of active Ru species16,56. In contrast, the OV/OL value was only slightly increased from 1.37 – 1.41 for Si-RuO2−0.1, indicating that the AEM pathway dominated the OER process, rather than the LOM pathway. This assertion was confirmed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (Fig. 6f), in which the signal intensity of OV at around 3513 G (g = 2.001) showed no obvious change57,58,59.

DEMS measurement

The above analysis indicated that the introduction of Si into RuO2 was capable of suppressed the LOM pathway during the OER process60. To validate this hypothesis from an experimental perspective, we carried out differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) using heavy-oxygen water (H218O) to detect the level of participation of lattice oxygen atoms during the OER process. The catalyst was first labeled by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a 0.1 M HClO4 solution containing H218O, and then the evolved O2 was measured in a 0.1 M HClO4 solution of H216O (see Fig. 7a and Methods). The signals of the evolved 34O2 reflected the direct 16O-18O coupling of 18O in the lattice and 16O in water17. As presented in the experimental results, the ratio of 34O2 to (32O2 + 34O2) was only 0.334% for Si-RuO2−0.1, which was only one-twentieth that of Com-RuO2 (6.72%) (Fig. 7b–d and Supplementary Fig. 16), indicating that the contribution of lattice oxygen to the OER was suppressed by ~95% on Si-RuO2−0.1 compared to Com-RuO2. Conclusively, the LOM pathway of the Si-RuO2−0.1 sample was greatly hindered, which is also giving strong support for its enhanced acidic OER stability.

In summary, we present a type of interstitial silicon-decorated RuO2 catalyst that exhibits high activity and stability toward the acidic OER. Si incorporation into the RuO2 lattice reduced the energy barrier of the RDS by optimizing the adsorption strength of *OOH intermediates onto active Ru sites, thus promoting OER performance. More importantly, we found that the robust Si-O bond formed by inserting acid-resistant Si into RuO2 interstices was able to weaken Ru-O bond covalency. Under the combined action of acid-resistant Si, strong Si-O interactions and weak Ru-O bond covalency, interstitial silicon-decorated RuO2 catalysts can suppress the LOM pathway in the OER for a long time, thereby exhibiting high stability. This work sheds light on the design of advanced catalysts with favorable stability toward the OER.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Ruthenium chloride hydrate (RuCl3•xH2O, 37.5 wt% Ru) and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, Si(OC2H5)4) were purchased from Chengdu Chron Chemical Reagent Limited Corporation (Chengdu, China). Commercial ruthenium oxide (RuO2) ( ≥ 99.99%) was obtained from Sigma‒Aldrich. A D113-type cation exchange resin (CER) was purchased from Tianjin Hongbomei Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium chloride (NaCl) and ethanol (C2H6O) were provided by Sinopharm LTD. The adsorbed water was removed from hydrous RuCl3 in a vacuum oven at 120 °C for 24 h, and then the RuCl3 was stored in a glove box with argon gas. The deionized water (DI) used in all experiments was obtained from a Millipore system.

Preparation of Si-RuO2-x (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3) catalysts

Typically, TEOS (334 μL) was dissolved in 30 mL of C2H6O to form a 0.05 mmol mL-1 TEOS solution. A total of 68 mg (or 0.25 mmol Ru) of dry RuCl3•xH2O powder was dissolved in 1 mL ultrapure water. Subsequently, 500 µL of 0.05 mmol mL-1 TEOS solution and the above RuCl3 solution were added to 1.5 g of powder-like CER in turn and then thoroughly ground for 30 min. After 2 h of rest, the as-obtained powder with TEOS and RuCl3 was dried at 60 °C for 8 h and then subjected to calcination in air under ambient pressure at 450 °C for 8 h. After the furnace cooled to room temperature, the black products were collected. The obtained products were washed several times with 40 mL of DI water at 80 °C and then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C to finally obtain the Si-RuO2−0.1 sample. To synthesize the Si-RuO2−0, Si-RuO2−0.05, Si-RuO2−0.2 and Si-RuO2−0.3 samples, the same procedure with the Si-RuO2−0.1 sample was used by changing the additive amount of TEOS solution (0 µL, 250 µL, 1000 µL and 1500 µL, respectively).

Material characterization

Powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD) was performed on a PANalytical X’pert with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å) at room temperature to obtain the crystalline structure of the samples. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) signals of the samples were collected with an ESCALAB250Xi spectrometer with an Al Kα light source (Al Kα, 1.4866 keV). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), a FEI Talos F200S instrument was used to characterize the microstructure of the samples under an accelerating voltage of 120 kV, and corresponding energy dispersive X-ray (EDS) mapping was employed to identify the element composition and distribution. A spherical-aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope (JEM-ARM200F) was used to identify the position of Si in RuO2. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker EMXPLUS spectrometer with a microwave frequency of 9.84 GHz. The K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) of Ru were recorded at the BL14W1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) (Shanghai, China).

Electrochemical measurements

A conventional three-electrode system in Gamry electrochemical workstation (Reference 3000) was employed to evaluate the electrochemical performance of the samples. Ag/AgCl (3.5 M KCl-saturated) and graphite rods (Φ = 6 mm) served as the reference electrode (RE) and counter electrode (CE), respectively. The catalyst ink was prepared by dispersing 4 mg of catalyst into a mixture of 1 mL isopropyl alcohol and 15 µL Nafion solution (5 wt.%), followed by ultrasonic dispersion. Then, 15 µL of the abovementioned ink was dropped onto a cleaned glassy carbon (GC) electrode (Φ = 5 mm) and dried under an infrared lamp to form the working electrode (WE) with the catalysts. In all experiments, the electrolyte was 0.1 M perchloric acid (HClO4) solution. Before testing, the Ag/AgCl electrode was calibrated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) using a purified Pt mesh as the WE in H2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte, and the average voltage value was recorded as \({E}_{c}\) when the current was zero. The value of \({E}_{c}\) was generally between 0.260 V and 0.270 V for the Ag/AgCl electrode in 0.1 M HClO4 solution. All potentials were calibrated relative to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) with iR compensation, according to the following calculations:

where \({E}_{{Ag}/{AgCl}}\) is the potential relative to the Ag/AgCl electrode, which is the set potential during all measurements, and \({E}_{c}\) is the potential of the Ag/AgCl electrode relative to the RHE. \({I}_{{mea}}\) is the measured polarization current. \({R}_{{sol}}\) is the solution resistance; the solution resistance of this test system was ~30 ohms.

To assess the true OER performance, the WEs were first subjected to 50 cycles of CV between 1.0 and 1.6 V (vs. RHE) at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 to stabilize the catalysts in an O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 solution. Then, linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was used to measure the OER polarization curve from 1.0 to 1.7 V (vs. RHE) at a sweep rate of 5 mV s−1 with a 1600 rpm rotation speed. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was obtained in the frequency range from 105 Hz to 10−2 Hz at a bias voltage of 1.4 V (vs. RHE) with a 10 mV amplitude. To investigate the stability of the catalysts, carbon paper (CP, with a surface area of 1 cm2) with 1.5 mg of catalyst was employed as the WEs, and then chronopotentiometry was used to record the E-t curve at a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

Inductively coupled plasma‒mass spectrometry (ICP‒MS) analysis of Ru ion dissolution

The ICP‒MS experiments were also carried out a NexION 5000 from Perkin Elmer to quantify the dissolution of Ru ions for Si-RuO2−0.1, Si-RuO2−0 and Com-RuO2 during the OER process. Carbon paper with 1.5 mg cm−2 catalysts was used as the WE, and electrolysis was performed at 10 mA cm−2 in 100 mL of 0.1 M HClO4 solution. Aliquots of 4 mL of electrolyte were removed after 3 h, 5 h, 10 h and 13 h of electrolysis and replaced with 4 mL of fresh electrolyte. The electrolyte aliquots were directly subjected to elemental analysis by ICP‒MS.

Based on the ICP‒MS results, the stability number (S-number) was also calculated using the following equation:

where \({N}_{{O}_{2}}\) is the total amount of evolved oxygen and \({N}_{{dis}}\) is the total amount of dissolved Ru ions according to the ICP‒MS results.

Differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS)

In situ DEMS involving heavy-oxygen water (H218O) was performed to identify the level of participation for lattice oxygen during the OER process in a QAS 100 device (see ref. 60. for details). The catalysts were dripped onto a porous gold (Au) disk electrode with a catalyst loading of 0.3 mg cm−2. The porous Au disk electrode with catalysts, Ag/AgCl electrode and pure Pt wire were used as the WE, RE and CE, respectively. First, the catalysts were labeled with 18O isotope by 5 CV cycles at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 in 0.1 M HClO4 solution containing H218O. Considering the difference in activity between Si-RuO2−0.1 and Com-RuO2, the potential range of CV cycles was set as 1.0-1.35 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for Si-RuO2−0.1 and 1.0-1.7 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for Com-RuO2 to achieve a similar current intensity. Then, the resulting electrodes were rinsed with 16O water several times to remove the residual H218O. Finally, the electrodes were placed in 0.1 M HClO4 containing H216O, and CV was carried out within the above potential windows. Meanwhile, mass spectrometry was used to detect O2 generated during the OER process in real time.

Theoretical calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted via the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). The electronic structures of materials were described by the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) and the projector augmented wave (PAW). The kinetic cutoff energy of the plane wave was fixed at 450 eV. The convergence tolerance of force and energy for each atom were 0.02 eV/Å and 10−5 eV, respectively.

A unit cell of pristine RuO2 contained 48 atoms, including 16 Ru atoms and 32 O atoms. On this basis, we constructed the \({{{\mbox{Ru}}}}_{16}{{{\mbox{Si}}}}_{2}{{{\mbox{O}}}}_{32}\) model based on the predicted Si content in the main text. During the structural optimization process, Brillouin zone integration was performed with 3 × 3 × 4 gamma k-point sampling. All atom and lattice parameters were free to vary. According to the principle of energy minimization, the most stable structure was selected to perform subsequent calculations. Detailed information on the modeled structures after optimization is provided in Supplementary Fig. 8-9 and Supplementary Table 2.

For the slab model, pristine RuO2 had a four-layer Ru-O structure, namely, 64 Ru atoms and 120 O atoms. The Si-RuO2 model contained four additional silicon atoms in the lattice interstices. The top two layers of Ru-O structures were relaxed, and the bottom two layers of Ru-O structures were set to be static to simulate the surface relaxation. Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling (2 × 2 × 1 and 4 × 4 × 1) was applied for geometric optimization and density of states (DOS) calculations.

To evaluate catalyst activity, models of the reaction intermediates (*OH, *O and *OOH) adsorbed onto the RuO2 and Si-RuO2 catalysts were also constructed, and each model was optimized to the most stable state. The free energy (ΔG) of each OER step was calculated according to the following equation:

where \(\Delta {E}_{{ZPE}}\) is the zero-point energy at 298.15 K; \(\Delta E\) is the binding energy of the intermediates; \(T\) is the experimental temperature (298.15 K); and \(\Delta S\) is the entropy change. Detailed information is present in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 3.

Data availability

All relevant data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file.

References

Yeo, K.-R., Lee, K.-S., Kim, H., Lee, J. & Kim, S.-K. A highly active and stable 3D dandelion spore-structured self-supporting Ir-based electrocatalyst for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis fabricated using structural reconstruction. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 3449–3461 (2022).

Pan, S. et al. Efficient and stable noble-metal-free catalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2294 (2022).

An, L. et al. Recent development of oxygen evolution electrocatalysts in acidic environment. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006328 (2021).

Spöri, C., Kwan, J. T. H., Bonakdarpour, A., Wilkinson, D. P. & Strasser, P. The stability challenges of oxygen evolving catalysts: towards a common fundamental understanding and mitigation of catalyst degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5994–6021 (2017).

Zheng, Y.-R. et al. Monitoring oxygen production on mass-selected iridium–tantalum oxide electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy 7, 55–64 (2022).

He, J., Zhou, X., Xu, P. & Sun, J. Regulating electron redistribution of intermetallic iridium oxide by incorporating Ru for efficient acidic water oxidation. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2102883 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Significantly enhanced overall water splitting performance by partial oxidation of Ir through Au modification in core–shell alloy structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4639–4645 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Exceptionally active iridium evolved from a pseudo-cubic perovskite for oxygen evolution in acid. Nat. Commun. 10, 572 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Core-shell nanostructured Ru@Ir–O electrocatalysts for superb oxygen evolution in acid. Small 18, 2108031 (2022).

Lin, C. et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 1012–1023 (2021).

Hao, S. et al. Torsion strained iridium oxide for efficient acidic water oxidation in proton exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1371–1377 (2021).

Seitz, L. C. et al. A highly active and stable IrOx/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science 353, 1011–1014 (2016).

An, L. et al. A functionally stable RuMn electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution eraction in acid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200131 (2022).

He, J., Li, W., Xu, P. & Sun, J. Tuning electron correlations of RuO2 by co-doping of Mo and Ce for boosting electrocatalytic water oxidation in acidic media. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 298, 120528 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Highly active ruthenium sites stabilized by modulating electron-feeding for sustainable acidic oxygen-evolution electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2356–2365 (2022).

Yao, Q. et al. S incorporated RuO2-based nanorings for active and stable water oxidation in acid. Nano Res. 15, 3964–3970 (2022).

Grimaud, A. et al. Activating lattice oxygen redox reactions in metal oxides to catalyse oxygen evolution. Nat. Chem. 9, 457–465 (2017).

Hao, S. et al. Dopants fixation of ruthenium for boosting acidic oxygen evolution stability and activity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5368 (2020).

Cui, X. et al. Robust interface Ru centers for high-performance acidic oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908126 (2020).

Miao, X. et al. Quadruple perovskite ruthenate as a highly efficient catalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3809 (2019).

Cao, L. et al. Dynamic oxygen adsorption on single-atomic ruthenium catalyst with high performance for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 10, 4849 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Engineering the electronic structure of single atom Ru sites via compressive strain boosts acidic water oxidation electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2, 304–313 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Zhu, X., Zhang, G., Shi, P. & Wang, A.-L. Rational catalyst design for oxygen evolution under acidic conditions: strategies toward enhanced electrocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 5890–5914 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. A Co-doped nanorod-like RuO2 electrocatalyst with abundant oxygen vacancies for acidic water oxidation. iScience 23, 100756 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Sodium-decorated amorphous/crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: a robust pH-universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18821–18829 (2021).

Lin, Y. et al. Chromium-ruthenium oxide solid solution electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 10, 162 (2019).

Su, J. et al. Assembling ultrasmall copper-doped ruthenium oxide nanocrystals into hollow porous polyhedra: highly robust electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution in acidic media. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801351 (2018).

Macounova, K., Makarova, M. & Krtil, P. Oxygen evolution on nanocrystalline RuO2 and Ru0.9Ni0.1O2−δ electrodes–DEMS approach to reaction mechanism determination. Electrochem. Commun. 11, 1865–1868 (2009).

Shi, Z. et al. Customized reaction route for ruthenium oxide towards stabilized water oxidation in high-performance PEM electrolyzers. Nat. Commun. 14, 843 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Iridium-containing water-oxidation catalysts in acidic electrolyte. Chin. J. Catal. 42, 1054–1077 (2021).

Chen, F.-Y., Wu, Z.-Y., Adler, Z. & Wang, H. Stability challenges of electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction: from mechanistic understanding to reactor design. Joule 5, 1704–1731 (2021).

Kasian, O., Grote, J.-P., Geiger, S., Cherevko, S. & Mayrhofer, K. J. J. The common intermediates of oxygen evolution and dissolution reactions during water electrolysis on iridium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2488–2491 (2018).

Dean, J. A. Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry 15th edn, Vol. 1424, 4.30–4.50 (McGraw-Hill Professional, 1999).

Pan, Y. et al. Direct evidence of boosted oxygen evolution over perovskite by enhanced lattice oxygen participation. Nat. Commun. 11, 2002 (2020).

Kim, D. et al. Blue-silica by Eu2+-activator occupied in interstitial sites. RSC Adv. 5, 74790–74801 (2015).

Gu, Y. et al. Crystal splintering of β-MnO2 induced by interstitial Ru doping toward reversible oxygen conversion. Chem. Mater. 33, 4135–4145 (2021).

Liu, C., Jiang, Y., Wang, T., Li, Q. & Liu, Y. Nano Si-doped ruthenium oxide particles from caged precursors for high-performance acidic oxygen evolution. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207429 (2023).

Ping, X. et al. Tailoring B-site of lead-ruthenate pyrochlore for boosting acidic water oxidation activity and stability. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 318, 121884 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Self-assembled ruddlesden–popper/perovskite hybrid with lattice-oxygen activation as a superior oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Small 16, 2001204 (2020).

Shen, Z. et al. Increased activity in the oxygen evolution reaction by Fe4+-induced hole states in perovskite La1−xSrxFeO3. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 4407–4415 (2020).

Huang, Z.-F. et al. Chemical and structural origin of lattice oxygen oxidation in Co–Zn oxyhydroxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy 4, 329–338 (2019).

Qin, Y. et al. RuO2 electronic structure and lattice strain dual engineering for enhanced acidic oxygen evolution reaction performance. Nat. Commun. 13, 3784 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. A porous pyrochlore Y2[Ru1.6Y0.4]O7–δ electrocatalyst for enhanced performance towards the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13877–13881 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Exceptionally active and stable RuO2 with interstitial carbon for water oxidation in acid. Chem 8, 1673–1687 (2022).

Wang, X., Zhong, H., Xi, S., Lee, W. S. V. & Xue, J. Understanding of oxygen redox in the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107956 (2022).

Hwang, J. et al. Perovskites in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Science 358, 751–756 (2017).

Liang, X. et al. Perovskite-type solid solution nano-electrocatalysts enable simultaneously enhanced activity and stability for oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001430 (2020).

Shin, J. F., Apperley, D. C. & Slater, P. R. Silicon doping in Ba2In2O5: example of a beneficial effect of silicon incorporation on oxide ion/proton conductivity. Chem. Mater. 22, 5945–5948 (2010).

Appel, C. C. & Bonanos, N. Structural and electrical characterisation of silica-containing yttria-stabilised zirconia. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 19, 847–851 (1999).

Ge, R. et al. Ultrafine defective RuO2 electrocatayst integrated on carbon cloth for robust water oxidation in acidic media. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901313 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Mn-doped RuO2 nanocrystals as highly active electrocatalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution in acidic media. ACS Catal. 10, 1152–1160 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Ultrahigh-loading of Ir single atoms on NiO matrix to dramatically enhance oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 7425–7433 (2020).

Shi, Z. et al. Confined Ir single sites with triggered lattice oxygen redox: toward boosted and sustained water oxidation catalysis. Joule 5, 2164–2176 (2021).

Geiger, S. et al. The stability number as a metric for electrocatalyst stability benchmarking. Nat. Catal. 1, 508–515 (2018).

Li, R. et al. IrW nanochannel support enabling ultrastable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution at 2 A cm−2 in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 12, 3540 (2021).

Xue, Y. et al. Sulfate-functionalized RuFeOx as highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalyst in acid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2101405 (2021).

Shi, Z. et al. Enhanced acidic water oxidation by dynamic migration of oxygen species at the Ir/Nb2O5−x catalyst/support interfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212341 (2022).

Liang, H. et al. Tungsten blue oxide as a reusable electrocatalyst for acidic water oxidation by plasma-induced vacancy engineering. CCS Chem. 3, 1553–1561 (2020).

Yu, B. et al. Densely populated tiny RuO2 crystallites supported by hierarchically porous carbon for full acidic water splitting. Mater. Horiz. 10, 4589–4596 (2023).

Wen, Y. et al. Stabilizing highly active Ru sites by suppressing lattice oxygen participation in acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6482–6490 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFB1506002, S.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 22178034, 21978028, S.C.; Grant Nos. 52021004, 91834301, Z.W.) and the Chongqing Talent Program (cstc2022ycjh-bgzxm0096, S.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. and Z.W. conceived the project. S.C. directed the main experimental works. S.C. and X.P. analyzed the experimental data. X.P. carried out the sample synthesis, characterization, electrochemical measurements. Y.L. carried out DFT calculation. L.Z. participated in some of the experimental work. Y. S. performed the electron-microscopy characterization. X.P., S.C., L.G. and Z.W. wrote the manuscript together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ping, X., Liu, Y., Zheng, L. et al. Locking the lattice oxygen in RuO2 to stabilize highly active Ru sites in acidic water oxidation. Nat Commun 15, 2501 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46815-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46815-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.