Abstract

High-harmonic generation in solids allows probing and controlling electron dynamics in crystals on few femtosecond timescales, paving the way to lightwave electronics. In the spatial domain, recent advances in the real-space interpretation of high-harmonic emission in solids allows imaging the field-free, static, potential of the valence electrons with picometer resolution. The combination of such extreme spatial and temporal resolutions to measure and control strong-field dynamics in solids at the atomic scale is poised to unlock a new frontier of lightwave electronics. Here, we report a strong intensity-dependent anisotropy in the high-harmonic generation from ReS2 that we attribute to angle-dependent interference of currents from the different atoms in the unit cell. Furthermore, we demonstrate how the laser parameters control the relative contribution of these atoms to the high-harmonic emission. Our findings provide an unprecedented atomic perspective on strong-field dynamics in crystals, revealing key factors to consider in the route towards developing efficient harmonic emitters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The foundational concept underpinning attosecond physics, and high-harmonic generation in gas-phase atoms and molecules in particular, is the energetic recollision of an electron ionized and accelerated by a strong laser field with the parent ion1,2,3,4. This dynamic real-space framework is instrumental to link the characteristics of the emitted harmonic radiation (amplitudes, phases and polarization) to sub-laser-cycle dynamics of atomic and molecular orbitals5,6,7,8,9. In solids, high-harmonic generation (HHG) is understood using a similar framework, albeit exchanging the real-space perspective for one in reciprocal space, where electron-hole pairs accelerate and recombine across energy bands in the Brillouin zone of the crystal10,11,12,13. This reciprocal-space approach has been paramount in virtually all investigations of solid-state high-harmonics: from revealing the role of electron-hole recollisions in the emission process14, to reconstructing the band structure of a ZnO crystal15, to explaining the multiple plateaus observed in the HHG spectrum16 and to map regions of crystal momenta where the electron-hole velocity vanishes17, among others18,19,20,21,22,23,24.

Despite the success of the reciprocal-space picture, a real-space approach offers a more intuitive framework, in particular in complex materials with many narrowly spaced and overlapping bands. The advantages of using a real-space perspective to understand HHG from solids are quickly starting to become apparent25,26,27, for example, in interpreting spatially-displaced electron-hole recollision processes27,28 or as means to directly reconstruct the field-free (static) valence electron potential at the picometer scale29. The possibility to link features of the high-harmonic spectrum to dynamics occurring at specific orbitals in the lattice remains, however, largely unexplored. Here, we demonstrate this possibility through angle-resolved measurements of HHG in ReS2. We measure a strong, intensity-dependent anisotropy of the HHG emission and trace it back to the interplay between the currents generated by each individual atom in the unit cell. Simulating the laser-matter interaction using a basis constructed from maximally-localized Wannier orbitals, we show that by changing the laser parameters (intensity and polarization), one can activate or suppress the contribution of specific atoms to the HHG emission and interfere the atomic currents differently, increasing or decreasing the high-harmonic emission efficiency.

Results

ReS2 is a layered semiconductor that crystallizes in a distorted octahedral (T) phase30,31,32,33,34. Figure 1a illustrates the unit cell of the monolayer, formed by 4 rhenium atoms and 8 sulfur atoms. The 4 Re clusters are linked in a chain oriented along θ = 120° (see panel a). While the anisotropy of the crystal structure is clear (the crystal symmetry group is P-1), the band structure is similar along different angles and is very dense (see Fig. 1b and Supplementary Note 1), and with a density of states near the Fermi energy significantly higher than other prototypical materials used in HHG spectroscopy, such as MgO or ZnO35. Going from the monolayer limit to bulk, these features remain, and the band structure changes only slightly30,31. In such dense band diagram, associating an individual harmonic with reciprocal space trajectories of charge carriers in a particular set of bands, according to the reciprocal-space method, is hardly straightforward (see circular markers in Fig. 1b–d), and is unlikely to provide much insight into the carrier dynamics. On the other hand, the small bandwidth indicates that the electrons are very localized on the individual atoms of the lattice, making it ideally suited for a real-space or orbital-based framework.

a Crystal structure, composed of 4 rhenium atoms and 8 sulfur atoms in a distorted octohedral structure. The unit cell is delimited by the parallelogram. b–d Band structure of the monolayer along (a) θ = 0∘, (b) θ = 60∘ and (c) θ = 120∘ (see panel a for definition of θ). Circular markers across the bands in panels b–d highlight vertical transitions resonant with the 11th harmonic (H11). Monolayer and bulk (see, e.g., references30,31) forms of ReS2 are both inversion symmetric and display a very similar electronic band structure, with a nearly identical direct band gap of 1.4 eV at the Γ point30,31.

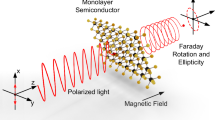

The first question we want to address is if high harmonics generated from ReS2 reflect the strong anisotropy apparent in real space or rather the weak angular dependence of its band structure. We generate high harmonics from bulk ReS2 with a linearly-polarized mid-infrared pulse with a duration of 80 fs and a center wavelength of 3.5 μm (see Methods). Figure 2a shows the high-harmonic spectrum measured for a laser intensity of 0.64 TW/cm2, measured in air, and polarization along θ = 120° (see inset). We observe odd harmonics extending up to the 13th order, while even harmonics are absent as expected from the inversion symmetry of ReS2. We measure the orientation dependence of the harmonics by rotating the polarization of the linear pulse with respect to the crystal. The results, shown in Fig. 2b–d, display a clear anisotropy for all harmonic orders. Furthermore, the anisotropy depends strongly on the laser intensity.

a High-harmonic spectrum for a laser intensity of 0.64 TW/cm2 and polarization along θ = 120∘ (parallel to the rhenium chains). The inset shows an optical micrograph of the bulk ReS2 flake using a CMOS camera and white-light illumination, with the longest edge corresponding to the rhenium chains. Orientation dependence of (b) H9, (c) H11 and (d) H13 for three different intensities: 0.25 TW/cm2 (blue), 0.64 TW/cm2 (green) and 0.76 TW/cm2 (red). We note that in the experiment, the intensity is measured in air before impinging on the material.

In order to understand the origin of this anisotropy, we perform time-dependent simulations in a basis constructed from 44 maximally-localized Wannier orbitals (see Methods for details)36. The similarity between the monolayer and bulk forms in the case of ReS230,31, allows us to reduce the computational complexity and simulate the monolayer system. The orientation dependence of H9 and H11 obtained from the numerical simulations is shown in Fig. 3a, b. While the uncertainty of the experimental intensities and the differences between the monolayer and bulk forms do not allow for a quantitative experiment-theory comparison (e.g., of the exact position of the harmonic maxima), our simulations clearly display the strong intensity-dependent anisotropy observed in the experiment. As a result, the simulations in monolayer ReS2 can provide valuable insight for the origin of this effect.

Full calculation of harmonics (a) H9 and (b) H11 for different intensities: 0.1 TW/cm2 (blue), 0.5 TW/cm2 (green) and 0.6 TW/cm2 (red). c Calculation neglecting the Fourier phase (solid lines) φn of the orbital current for H11 for 0.1 TW/cm2 (blue) and 0.6 TW/cm2 (red). For comparison, the full calculation curves of panel b are shown in c with dashed, faint lines. We note that in the simulations, the intensity refers to that inside the material.

The high-harmonic spectrum is given by the Fourier components of the time-dependent current that is generated by the laser-induced oscillating dipole of the medium (see Methods),

where Jα(t) is the total current along direction α = (∥, ⊥), corresponding to the components parallel and perpendicular to the electric field of the driving laser, respectively. The total current can be expressed as a sum of currents from all the orbitals in the lattice, \({J}_{\alpha }(t)=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{n}^{{N}_{{{{{{{{\rm{orb}}}}}}}}}}{J}_{n,\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{(W)}}}}}}}}}(t)\), where \({J}_{n,\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{(W)}}}}}}}}}(t)\) represents the contribution to the total current of the changing population of orbital n and its coherence with all other orbitals (see Methods). The superscript (W) indicates that such orbital currents are defined in the Wannier gauge and, even if they are not observable, provide a unique real-space perspective into the HHG process. Expressed in terms of the individual orbital currents, the high-harmonic spectrum is

where An,α and φn,α are, respectively, the spectral amplitude and phase of the current of orbital n along direction α.

Equation (2) allows us to distinguish features that arise from the interference of different orbital currents. The incoherent sum of the individual currents, \({I}_{\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{incoh}}}}}}}}}(\omega )=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{n}^{{N}_{{{{{{{{\rm{orb}}}}}}}}}}{\left|{{{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}}}}[\,{J}_{n,\alpha }^{(W)}(t)](\omega )\right|}^{2}\), will be absent of such interference. In Fig. 3c we compare the angle-dependent harmonic yield of H11 for \({I}_{\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{incoh}}}}}}}}}\) (solid lines) and the observable signal Iα (faint dashed lines). A similar analysis for H9 is made in Supplementary Note 2. The angular variation is stronger for Iα, with near-complete suppression of various secondary maxima that are present in \({I}_{\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{incoh}}}}}}}}}\) (most notably near 60°), strongly modifying the orientation dependence. Thus, orbital phase interference is an important factor determining the orientation dependence.

Since the electrons are well localized on each atomic site (see Supplementary Data 1), we can group together the currents of the m orbitals belonging to the same atom A into an atomic current, \({J}_{A,\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{(W)}}}}}}}}}(t)={\sum }_{m}{J}_{m,\alpha }^{{{{{{{{\rm{(W)}}}}}}}}}(t)\). Furthermore, due to the inversion symmetry of ReS2, each atom is related to one other by an inversion operation, for example, Re1 and Re3 or S1 and S6 (see Fig. 1a). Both of the atoms in the pair give rise to the same Fourier amplitudes and phases, so that the total harmonic spectrum in Eq. (2) reduces to the sum of the Fourier amplitudes and phases of six atomic (inversion-related) pairs.

Figure 4 a, b show the Fourier amplitudes and phases of the six atomic pairs, indicated with different colors, for H11 along α = ∥ and for two intensities: 0.1 TW/cm2 and 0.6 TW/cm2. At both low and high intensities (Fig. 4a, b respectively) emission is spread over a wide range of phases at any given angle. For the lowest intensity (Fig. 4a), every atomic pair contributes a similar amplitude to the emission near θ = 40–60°, but their phases are spread equally over π rad, thus leading to the near-perfect destructive interference seen in Fig. 3b (blue curve) at these angles. On the other hand, for angles close to θ = 100°, the Fourier phases from the different atomic sites are similar, leading to constructive interference in Eq. (2) and therefore to the peak observed in Fig. 3b (blue curve). At θ = 100°, the atomic pair Re2-Re4, which contributes the most to H11 at low intensity, is largely suppressed at high intensity (compare size of orange circle in Fig. 4a, b). This analysis shows that atoms that do not contribute to the generation of a particular harmonic order for one driver intensity, can be activated for other intensities, and vice versa, suggesting that laser intensity could be used as a mechanism to control the relative weight of atomic orbitals in HHG. An analogous analysis can be made for the rest of harmonic orders, along both α = ∥, ⊥ directions (see Supplementary Note 2), where we observe a larger spread of the Fourier phases for increasing harmonic orders. This leads to sharper changes in the angle-resolved spectrum for higher orders, as also seen in the experiment.

The circles colors represent the six different atomic pairs, the size of each circle is proportional to the Fourier amplitude ∣An∣ and the Fourier phase φn is given in the vertical axis. The panels display the Fourier amplitudes ∣An∣ and phases φn of the six atomic pairs (inversion-symmetric partners) as a function of the laser polarization angle for H11. Two driver intensities are shown: a 0.1 TW/cm2 and b 0.6 TW/cm2. The results shown are for the harmonic polarization α that is parallel to the electric field.

In conclusion, we identify how the nonlinear currents residing on each of the twelve atoms in the unit cell of a ReS2 crystal are responsible for the strongly anisotropic and intensity-dependent emission of high-order harmonics. Our orbital analysis based on maximally localized Wannier functions reveals that each atomic contribution depends strongly on the polarization angle and intensity of the driving field, paving the way to characterizing and controlling electron dynamics at the picometer-scale in solids on sub-laser-cycle timescales. Moreover, we show that interference between atoms in the unit cell of a crystal is key to determine the macroscopic high-harmonic emission, a critical factor to consider in the route towards developing efficient harmonic emitters.

Methods

Experimental methods

ReS2 flakes were mechanically exfoliated from an extracted section of a bulk sample using tape, then dispersed across the tape by folding over itself to reduce thickness and produce generally flat flakes. The ReS2 crystal was transferred from the tape to a PDMS stamp, then transferred from the stamp to the substrate at 80°. The substrate consists of a two-side polished, 10 × 10 × 0.5 mm, (100)-cut MgO single crystal that is cleaned with acetone and isopropanol. The PDMS stamp was peeled off to leave the bulk ReS2 flakes on the MgO substrate.

The sample is imaged in-situ with a white-light source as well as the laser source, allowing sample areas of interest to be located and crystallographic orientation to be measured.

The laser source consists of a Yb:KGW laser (LightConversion Carbide CB3) delivering 200fs pulses at a center wavelength of 1030 nm with a repetition rate of 100 kHz and average power of 80 W. A portion of this power (60 W) pumps a commercial optical parametric amplifier (LightConversion Orpheus-MIR), generating mid-infrared pulses at a wavelength of 3.5 μm with a bandwidth that sustains a 60 fs pulse. An Ag off-axis parabolic mirror focuses the mid-infrared beam onto the sample, producing high harmonics. The size of the focus is estimated from the size of the damaged region of the flake after illuminating it at a high power and was measured to be 58 ± 15 μm. The intensity was then obtained from the focus size, pulse duration, repetition rate and measured power, yielding values compatible with those from theory within a range of 60%. The generated high harmonics are collected in transmission geometry and focused on the input slit of a Princeton Instruments IsoPlane spectrometer with an Al spherical mirror of 15 cm focal length. A half-wave plate is positioned between the parabolic mirror and the sample to rotate the linear laser polarization with respect to the crystal axis.

Numerical methods

The field-free Hamiltonian and dipole couplings of monolayer ReS2 were calculated with the electronic structure code Quantum Espresso37 on a Monkhorst–Pack (MP) grid of 12 × 12 × 1 points using a norm-conserving Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange correlation functional. The field-free Hamiltonian used in the time-dependent propagation was constructed by projecting the Bloch states onto a set of maximally-localized Wannier functions using the Wannier90 code36. In particular, we projected onto the d orbitals of the four rhenium atoms and the p orbitals of the six sulfur atoms, totaling 44 bands. The Hamiltonian in the basis constructed from Wannier functions was then propagated in the presence of the electric field using the density matrix formalism with the code described in ref. 26. The large size of the unit cell allowed us to obtain convergence with a modest MP grid of 50 × 50 k-points along the b1 and b2 reciprocal lattice vectors. The time step was set to 0.2 a.u. and the dephasing time was chosen to be T2 = 10 fs. While the exact position of the peaks and the broadness of the angular features at fixed intensities depend on the choice of dephasing time, the intensity-dependent strong anisotropy observed is independent on the choice of T2, as well as on small changes of the central wavelength (see Supplementary Note 3).

The time-dependent current along direction α, used to extract the high harmonic spectrum, is defined as

Above, e is the electron charge, Nk is the number of crystal momenta included in the calculation, \(\hat{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}\) is the velocity operator, and ρ is the density matrix. In the Wannier gauge, the density matrix ρ(W) contains the orbital populations and coherences in its diagonal and off-diagonal terms, respectively. In the Wannier gauge, we may define a (real) current from an individual orbital n along direction α as

such that the sum of the currents from all orbitals equals the total current,

For clarity, we give an example for a two-orbital model, although we point out that our analysis is only relevant for multi-orbital crystals as the one presented in this work. In the two-orbital case,

where the subscripts 1 and 2 identify the orbital and α = ∥, ⊥ the direction of current emission. Since both the velocity and density matrices are hermitian, the current of an individual orbital is composed of a term associated to the population change of that orbital, plus exactly half of the contribution of the coherence between that orbital and the rest. Thus, this approach offers a way of quantifying the contribution of individual orbitals, and their interference, to the high-harmonic generation.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Three numerical codes were used in this work: Quantum Espresso, Wannier90 and Iweria. The first two are open-source and can be found, respectively, in https://www.quantum-espresso.org/and https://wannier.org/. Iweria is an in-house code described in ref. 26, and parts of it relevant to reproducing the results of this work can be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Corkum, P. B. Plasma perspective on strong-field multiphoton ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 1994–1997 (1993).

Krause, J. L., Schafer, K. J. & Kulander, K. C. High-order harmonic generation from atoms and ions in the high intensity regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3535–3538 (1992).

Lewenstein, M., Balcou, P., Ivanov, M. Y., L’Huillier, A. & Corkum, P. B. Theory of high-harmonic generation by low-frequency laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 49 (1994). https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.49.2117.

Krausz, F. & Ivanov, M. Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 163–234 (2009).

Levesque, J., Zeidler, D., Marangos, J. P., Corkum, P. B. & Villeneuve, D. M. High harmonic generation and the role of atomic orbital wave functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 183903 (2007).

Smirnova, O. et al. High harmonic interferometry of multi-electron dynamics in molecules. Nature 460, 972–977 (2009).

Wörner, H. J., Bertrand, J. B., Kartashov, D. V., Corkum, P. B. & Villeneuve, D. M. Following a chemical reaction using high-harmonic interferometry. Nature 466, 604–607 (2010).

Cireasa, R. et al. Probing molecular chirality on a sub-femtosecond timescale. Nat. Phys. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3369 (2015).

Kraus, P. M., Zürch, M., Cushing, S. K., Neumark, D. M. & Leone, S. R. The ultrafast X-ray spectroscopic revolution in chemical dynamics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 82–94 (2018).

Vampa, G. et al. Linking high harmonics from gases and solids. Nature 522, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14517 (2015).

Kruchinin, S. Y., Krausz, F. & Yakovlev, V. S. Colloquium: Strong-field phenomena in periodic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 21002 (2018).

Yue, L. & Gaarde, M. B. Introduction to theory of high-harmonic generation in solids: tutorial. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 39, 535–555 (2022).

Goulielmakis, E. & Brabec, T. High harmonic generation in condensed matter. Nat. Photonics 16, 411–421 (2022).

Vampa, G. et al. Theoretical analysis of high-harmonic generation in solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 73901 (2014).

Vampa, G. et al. All-optical reconstruction of crystal band structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 193603 (2015).

Ndabashimiye, G. et al. Solid-state harmonics beyond the atomic limit. Nature 534, 520–523 (2016).

Uzan, A. J. et al. Attosecond spectral singularities in solid-state high-harmonic generation. Nat. Photonics 14, 183–187 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. High-harmonic generation from an atomically thin semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 13, 262–265 (2017).

Bauer, D. & Hansen, K. K. High-harmonic generation in solids with and without topological edge states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 177401 (2018).

Luu, T. T. et al. Extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic spectroscopy of solids. Nature 521, 498–502 (2015).

Langer, F. et al. Lightwave-driven quasiparticle collisions on a subcycle timescale. Nature 533, 225 (2016).

Jiménez-Galán, Á., Silva, R. E. F., Smirnova, O. & Ivanov, M. Sub-cycle valleytronics: control of valley polarization using few-cycle linearly polarized pulses. Optica 8, 277–280 (2021).

Amini, K. et al. Symphony on strong field approximation. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 116001 (2019).

Franz, D. et al. All semiconductor enhanced high-harmonic generation from a single nanostructured cone. Sci. Rep. 9, 5663 (2019).

Osika, E. N. et al. Wannier-bloch approach to localization in high-harmonics generation in solids. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021017 (2017).

Silva, R. E. F., Martín, F. & Ivanov, M. High harmonic generation in crystals using maximally localized Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 100, 195201 (2019).

Parks, A. M. et al. Wannier quasi-classical approach to high harmonic generation in semiconductors. Optica 7, 1764–1772 (2020).

Yue, L. & Gaarde, M. B. Imperfect recollisions in high-harmonic generation in solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 153204 (2020).

Lakhotia, H. et al. Laser picoscopy of valence electrons in solids. Nature 583, 55–59 (2020).

Tongay, S. et al. Monolayer behaviour in bulk ReS2 due to electronic and vibrational decoupling. Nat. Commun. 5, 3252 (2014).

Gehlmann, M. et al. Direct observation of the band gap transition in atomically thin ReS2. Nano Lett. 17, 5187–5192 (2017).

Wolverson, D., Crampin, S., Kazemi, A. S., Ilie, A. & Bending, S. J. Raman spectra of monolayer, few-layer, and bulk ReSe2: an anisotropic layered semiconductor. ACS Nano 8, 11154–11164 (2014).

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Single-layer ReS2: two-dimensional semiconductor with tunable in-plane anisotropy. ACS Nano 9, 11249–11257 (2015).

Plumadore, R. et al. Prevalence of oxygen defects in an in-plane anisotropic transition metal dichalcogenide. Phys. Rev. B 102, 205408 (2020).

For a comparison of the density of states near the Fermi energy of ReS2, MgO and ZnO, see https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-572758, https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-1265 and https://materialsproject.org/materials/mp-2133.

Marzari, N., Mostofi, A. A., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions: theory and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1419–1475 (2012).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank David Crane, Ryan Kroeker and Andrei Naumov for continued technical support. A.J.G. acknowledges support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement (101028938), from Comunidad de Madrid through TALENTO Grant 2022-T1/IND-24102 and from the Joint Center for Extreme Photonics. G.V. acknowledges support from the Joint Center for Extreme Photonics and the National Research Council’s Quantum Sensing program. D.V. acknowledges support from the Joint Center for Extreme Photonics. R.E.F.S. acknowledges support from the fellowship LCF/BQ/PR21/11840008 from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. and G.E. performed the experiments; A.J.G. performed the numerical analysis and calculations; A.P. and R.E.F.S. performed ancillary calculations; R.E.F.S. developed the numerical code; D.M.V., A.S., T.B., A.L.M. and G.V. supervised the work. A.J.G. and G.V. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Balázs Major, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez-Galán, Á., Bossaer, C., Ernotte, G. et al. Orbital perspective on high-harmonic generation from solids. Nat Commun 14, 8421 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44041-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44041-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.