Abstract

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are associated with cardiometabolic diseases and social inequities. For most nations, recent estimates and trends of intake are not available; nor variation by education or urbanicity. We investigated SSB intakes among adults between 1990 and 2018 in 185 countries, stratified subnationally by age, sex, education, and rural/urban residence, using data from the Global Dietary Database. In 2018, mean global SSB intake was 2.7 (8 oz = 248 grams) servings/week (95% UI 2.5-2.9) (range: 0.7 (0.5-1.1) in South Asia to 7.8 (7.1-8.6) in Latin America/Caribbean). Intakes were higher in male vs. female, younger vs. older, more vs. less educated, and urban vs. rural adults. Variations by education and urbanicity were largest in Sub-Saharan Africa. Between 1990 and 2018, SSB intakes increased by +0.37 (+0.29, +0.47), with the largest increase in Sub-Saharan Africa. These findings inform intervention, surveillance, and policy actions worldwide, highlighting the growing problem of SSBs for public health in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

What people eat and drink is one of the most important determinants of health as well as health equity1. In 2019, poor dietary habits, overweight/obesity, and undernutrition contributed to 14%, 10%, and 5% of deaths in females, respectively; and 15%, 8%, and 5% of deaths in males2. Most of these diet-related health burdens were due to cardiometabolic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes (T2D), and cancer. These diet-related conditions not only reduce quality of life and productivity but are also leading risk factors for worse clinical outcomes from COVID-193. Therefore, improving diets to reduce deaths, complications, and economic and equity burdens from cardiometabolic diseases should be a global priority.

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are a priority concern given their relationship with obesity, CVD, T2D, cancer, and dental caries4,5,6; absence of any offsetting nutritional benefits7; intensive marketing to traditionally marginalized populations8; and contribution to health disparities9. Yet, for the vast majority of nations, recent national estimates of SSB intake are unavailable, preventing an analysis of the evolving (and potentially nonlinear) trends in intake in recent decades. Furthermore, prior global estimates have not evaluated SSB intake subnationally by important sociodemographic factors such as education or urbanicity. This lack of evidence limits the ability to design and measure the impact of interventions aimed at decreasing SSB intake, as well as the capacity to identify populations where such interventions are needed the most.

In an investigation based on 2010 data, 184,000 global deaths were estimated to be attributable to SSB intake, including 72.3% from T2D, 24.2% from CVD, and 3.5% from obesity-related cancers4. Since that time, national and subnational dietary data from a handful of high-income nations suggest that SSB intake has decreased in selected high-income Western countries10,11,12,13,14,15 and Brazil16. However, energy contribution from SSBs remains high in these nations; and SSB intake may be increasing, based on limited national intake and sales reports, in non-Western countries such as Korea17 and India18. More recent, harmonized, and subnationally stratified data on SSB intakes are needed to inform intervention, surveillance, and policy actions. To address these knowledge gaps, we investigated SSB intakes in adults aged 20+ years in 1990, 2005, and 2018 in 185 countries, jointly stratified subnationally by age, sex, education, and area of residence, based on new data from the Global Dietary Database (GDD).

In this work, we show that intakes were higher in male vs. female, younger vs. older, more vs. less educated, and urban vs. rural adults, and that variations by education and urbanicity were largest in Sub-Saharan Africa. SSB intakes increased between 1990 and 2018 by +0.37 servings/week (+0.29, +0.47), with the largest increase in Sub-Saharan Africa, and an overall decrease in Latin America/Caribbean. These new findings on global SSB intakes, trends, and inequities inform intervention, surveillance, and policy actions worldwide, highlighting the growing problem of SSBs for public health in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Results

Global, regional, and national SSB intakes in 2018

In 2018, the mean global intake of SSBs among adults was 2.7 8 oz (248 grams) servings/week (95% UI 2.5, 2.9), varying across world regions by 10-fold, from 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) in South Asia to 7.8 (7.1, 8.6) in Latin America/Caribbean (Table 1). Among the 25 most populous countries worldwide, the highest intakes were in Mexico (8.9 [8.2, 9.8]), followed by Ethiopia (7.1 [5.6, 8.9]), the United States (4.9 [4.6, 5.1]), and Nigeria (4.9 [3.2, 7.2]), while the lowest intakes were in India, China, and Bangladesh (0.2 servings/week each) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 2). Of 185 countries, 58 (31.4%), representing 446 million adults or 8.9% of the adult world population, had a mean SSB intake of 7+ servings/week.

SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). For this visual representation, values were truncated at 21 servings/week to better reflect the distribution of intakes globally. The analysis of the data was done using the rworldmap package (v1.3-6). Source data are provided as Source Data file 1. Oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages.

SSB intakes by sex and age in 2018

Globally, regionally, and nationally, males had modestly higher energy-adjusted SSB intake than females (Table 1, Supplementary Table 6). The largest sex differences by region were in High-Income Countries and Latin America/Caribbean, where males consumed 0.5+ servings/week more than females across all strata (Supplementary Table 7). For example, in Latin America/Caribbean, males consumed 8.2 servings/week; and females, 7.4 servings/week. Among the 25 most populous countries, the largest differences in SSB intake between males and females were in the US, Mexico, and France, where males had 1+ serving/week higher intake overall and stratified by age, education, and urbanicity (Supplementary Table 8).

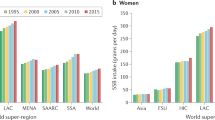

By age, SSB intakes were higher at younger vs. older ages in all regions, though with varying absolute magnitudes of intakes and differences by region (Table 1; Fig. 2). For instance, in Latin America/Caribbean, where intakes were the highest compared to all regions, adults age 20–24 years had a mean SSB intake of 11.1 servings/week while adults age 85+ years had a mean intake of 3.9 servings/week. In contrast, in South Asia, where intakes were the lowest across all regions, intakes were 1.0 servings/week and 0.4 servings/week in adults age 20–24 and 85+ years respectively. Regionally, patterns of intake by age were similar between males and females (Supplementary Fig. 2). Highest weekly servings by age and region were in Latin America/Caribbean among young adults (20–24 years: 11.1; 25–29 years: 10.2), and lowest among adults age 75+ years from South Asia and 60+ years from Southeast and East Asia (~0.4 each) (Table 1). Among the 25 most populous countries, the highest intakes were among adults age 20–39 years from Mexico (11.0) and Ethiopia (7.8), and the lowest intake was among adults age 60+ years in China, India, and Bangladesh (~0.1–0.2 each) (Supplementary Table 6).

SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled circles represent the mean SSBs intake (8 oz serving/week) and the error bars of the 95% UIs. Age groups are 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85+ years. In prior GDD reports, the region Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia was referred as Former Soviet Union, and Southeast and East Asia was referred to as Asia. Source data are provided as Source Data file 2. Centr/East Eur & Centr Asia, Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, GDD Global Dietary Database, Latin Amer/Caribbean Latin America/Caribbean, oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals.

SSB intakes by education and residence in 2018

Globally, SSB intakes varied substantially by region and education. Intakes were higher among more vs. less-educated adults in Sub-Saharan Africa (+4.68 weekly servings higher; +87.9% relative difference), South Asia (+2.00; +356.6%), and Latin America/Caribbean (+1.31; +18.3%), but lower among more vs. less-educated adults in Middle East/North Africa (−1.23; −25.2%); with smaller differences by education in other regions (Supplementary Table 7). Differences by high vs. low education decreased as age increased in all world regions, with the largest differences by education in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 3a). By urbanicity, the largest differences by education were among urban and rural adults in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 3b).

a Difference SSB intakes in high vs. low educated adults by age. b difference in SSB intakes in high vs. low educated adults by area of residence. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled bars represent the mean difference in SSBs intake (8 oz serving/week) and the error bars the 95% UIs. Values were truncated at −2.0 and 5.8 (8 oz) servings/week to better represent the distribution of intakes. Upper and lower 95% UIs above or below those values are displayed with a dashed line. Colors represent the age category as “20–30 years” (orange), “40–59 years” (red), or “60+ years” (dark red); and the area of residence as “rural” (light blue) or “urban” (dark blue). In prior GDD reports, the region Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia was referred to as Former Soviet Union, and Southeast and East Asia was referred to as Asia. Source data are provided as Source Data file 3. Centr/East Eur & Centr Asia Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, GDD Global Dietary Database, Latin Amer/Caribbean Latin America/Caribbean, oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals.

Among the 25 most populous countries, the largest differences in SSB intake in high vs. low-educated adults were in Pakistan, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, where more-educated adults tended to have 3+ servings/week higher intake than less-educated adults (Supplementary Table 9).

By urbanicity, global intakes were 57.3% higher in urban (3.2) vs. rural (2.0) areas (absolute difference: +1.17) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 7). By region, this pattern was most prominent in Sub-Saharan Africa (+2.67; +48.3%) and South Asia (+1.17; +340.6%); was much smaller in other regions; and was inverted in Middle East/North Africa (with lower intakes in urban regions: −0.81; −16.1%). Differences by urbanicity decreased as age increased in all regions, with largest differences in urban vs. rural adults in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 4a). By region and education, differences between urban and rural areas were larger among higher educated adults in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, but smaller among high educated adults in Middle East/North Africa, with little variation in other regions (Fig. 4b). Among the 25 most populous countries, largest differences by urbanicity were in Pakistan, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, where adults from urban vs. rural areas tended to have 2+ servings/week greater intake (Supplementary Table 10).

a Difference in SSB intakes in adults from urban vs. rural areas by age. b difference SSB intakes in adults from urban vs. rural areas by education. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled bars represent the mean difference in SSBs intake (8 oz serving/week) and the error bars the 95% UIs. Values were truncated at −2.0 and 5.8 (8 oz) servings/week to better represent the distribution of intakes. Upper and lower 95% UIs above or below those values are displayed with a dashed line. Colors represent the age category as “20–30 years” (orange), “40–59 years” (red), or “60+ years” (dark red); and education level as “low” 0–6 years of education (light green), “medium” >6 years to 12 years of education (dark green), or “high” >12 years of education (purple). In prior GDD reports, the region Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia was referred to as Former Soviet Union, and Southeast and East Asia was referred to as Asia. Source data are provided as Source Data file 4. Centr/East Eur & Centr Asia, Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia; GDD Global Dietary Database; Latin Amer/Caribbean, Latin America/Caribbean, oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals.

Globally, intakes were higher in urban vs. rural areas. However, regionally this was only the case in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia; whereas the intake was inverse in Middle East/North Africa; and intakes were almost the same between urban and rural areas in all other regions (Fig. 5a). Stratified by both education and area of residence, globally, urban adults had higher intakes than rural adults at all education levels (Fig. 5b). However, by region, this pattern was only observed in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, was not notable in most other regions, and was reversed (higher intakes in rural vs. urban adults at all education levels) in Middle East/North Africa.

a SSB intakes in adults by area of residence. b SSB intakes in adults by area of residence and education level. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars having ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled bars represent the mean SSBs intake (8 oz servings/week) and the error bars the 95% UIs. Values were truncated at 14.5 (8 oz) servings/week to better reflect the distribution of intakes. Upper 95% UIs above that value are shown with a dashed line. The values below the bars correspond to the percentage (%) of the global population represented in that strata. Colors represent the education level as “low” 0 to 6 years of education (light green), “medium” >6 years to 12 years of education (dark green), or “high” >12 years of education (purple); and area of residence as “rural” (light blue) or “urban” (dark blue). In prior GDD reports, the region Central or Eastern Europe and Central Asia was referred to as Former Soviet Union, and Southeast and East Asia was referred as Asia. Source data are provided as Source Data file 2. GDD Global Dietary Database, oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals.

Strikingly, assessing both education and urbanicity by region, the highest intakes globally were among highly educated adults from urban Sub-Saharan Africa (12.4), representing 3.2% of the regional population; medium educated adults from urban Sub-Saharan Africa (11.2), representing 10.2% of the regional population; and high educated adults from urban Latin America/Caribbean (8.5), representing 15.8% of the regional population. Detailed global, regional, and national SSB intakes for 1990 and 2005 are in Supplementary Tables 11–14 and Supplementary Figs. 3–7.

Trends in SSB intakes between 1990, 2005, and 2018

Globally, SSB intake increased from 1990 to 2018 by +0.37 servings/week ([95% UI 0.29, 0.47]; +15.9%) (Supplementary Data 2). Of note, the increase was larger from 1990 to 2005 (+0.22 [0.17, 0.28]; +9.3%) than from 2005 to 2018 (+0.15 [0.11, 0.21]; +6.0%). However, regional changes were highly heterogenous. Between 1990 and 2005, the largest regional increases occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa (+1.04 [0.65, 1.63]; +28.6%) and High-Income Countries (+1.02 [0.94, 1.10]; +26.9%), while large decreases occurred in Latin America/Caribbean (−1.23 [−1.43, −1.03], −14.8%) (Fig. 6, Supplementary Data 2). In contrast, from 2005 to 2018, Sub-Saharan Africa experienced the largest increase (+1.93 [1.53, 2.37]; +41.4%), while High-Income Countries experienced a significant decrease (−1.11 [−1.19, −1.03]; −23.0%). Overall, from 1990 to 2018, the largest increase was in Sub-Saharan Africa (+2.99 [2.26, 3.89]; +81.9%), while intakes rose then fell in High-Income Countries, returning close to 1990 levels by 2018. Other world regions had more modest, steady increases over time.

a Mean SSB intakes by world region in 1990, 2005, and 2018. b absolute changes in SSB intakes from 1990–2005, 2005–2018, and 1990–2018. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milkks. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled bars represent the mean intake (a) and the absolute change in the mean intake (b), and the error bars represent the 95% UIs. Values in (b) were truncated at 3.5 (8 oz) servings per week to better reflect the distribution of change in intakes. Upper 95% UIs above that value are shown with a dashed line. In prior GDD reports, the region Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia was called the Former Soviet Union, and Southeast and East Asia was called Asia. Source data are provided as Source Data files 2 and 6. GDD Global Dietary Database, oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals, World regions CEECA, Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, HIC High-Income Countries, LAC Latin America/Caribbean, MENA Middle East/North Africa, SA South Asia, SEEA Southeast and East Asia, SSA Sub-Saharan Africa.

Energy-adjusted SSB intakes and trends were generally similar in males vs. females (Supplementary Table 15). By age, globally, and in most regions, SSB intake increased across all age groups in both time periods. However, in Latin America/Caribbean from 1990 to 2005 and in High-Income Countries from 2005 to 2018, SSB intakes decreased across all age categories. By age and region, from 1990 to 2018 SSB intakes increased most in Sub-Saharan African adults aged 20-39 (+3.28 [2.49, 4.26]; +83.3%), age 40–59 (+2.71 [1.98, 3.66]; +79.8%), and age 60+ years (+1.91 [1.28, 2.80]; +74.9%). Similarly, by education level and region, SSB intakes decreased from 1990 to 2005 in Latin America/Caribbean and from 2005 to 2018 in High-Income Countries in all education groups, while increases (or minor decreases) were seen in other regions across all education groups in both time periods (Supplementary Table 15). By education and region, from 1990 to 2018 the largest increases were in Sub-Saharan Africa among medium (+3.70 [2.69, 4.97]; +69.2%), high (+2.89 [1.95, 4.06]; +40.3%) and low (+2.72 [2.02, 3.63]; +103.6%) educated adults. Globally, SSB intakes increased from 1990 to 2018 in urban areas (+0.24 [0.16, 0.33]; +8.0%) and even more so in rural areas (+0.53 [95% UI 0.44, 0.65]; +35.3%). However, trends by urbanicity were highly heterogeneous across world regions, with larger increases in urban vs. rural areas in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa; a notable decrease in urban but not rural Latin America/Caribbean, and an increase then decrease in both urban and rural areas in High-Income Countries and South Asia.

Among populous countries, the largest increases from 1990 to 2005 were in Nigeria (+4.15; +785.6%) and the US (+2.27; +42.3%); and the largest decrease in Brazil (−2.97; −40.8%) (Fig. 7, Supplementary Data 2). From 2005 to 2018, the largest increases were in Thailand (+2.09; +84.5%) and Ethiopia (+1.67; +30.8%), while the US experienced the largest decrease (−2.79; −36.5%). Overall, between 1990 to 2018, Nigeria had the largest increase (+4.33; +821.6%), followed by Thailand (+3.87; +554.9%) and Ethiopia (+3.34; +89.5%); and Brazil, the largest decrease (−2.90; −39.8%) (Supplementary Fig. 7). Trends over time by age, sex, education, and urbanicity within the 25 most populous countries are in Supplementary Discussion 1 and Supplementary Tables 15–19.

a Mean SSB intakes in the 25 most populous countries in 2018. b absolute change in SSB intakes from 1990 to 2005. c absolute change in SSB intakes from 2005 to 2018. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 grams). The filled bars represent the mean SSB intakes (8 oz serving/week) and the error bars the 95% UIs. Values were truncated at 5.0 (8 oz) servings/week for b and at 2.5 (8 oz) servings/week for c. Upper 95% UIs above those values are shown with a dashed line. Countries are ordered left to right from most to least populous based on 2018 adult (20+ years) population data. Source data are provided as Source Data files 1 and 7. Oz ounces, SSBs sugar-sweetened beverages, UIs uncertainty intervals.

National SSB intakes and trends according to SDI

In both 1990 and 2005, national SDI was not related to SSB intake (r = 0.036, p = 0.63; r = −0.029, p = 0.69; respectively) (Fig. 8). However, by 2018, an inverse correlation was evident between national SDI and SSB intake (r = −0.21, p = 0.004), with generally higher national intakes in countries with lower SDI.

a National correlation of SSB intakes adults and SDI by world region in 1990 and b national correlation of SSB intakes adults and SDI by world region in 2018. Person correlation was assessed between SDI and SSB intakes among a total of 185 countries were included in this analysis. SSBs were defined as any beverage with added sugars having ≥50 kcal per 8 oz serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excludes 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. The standardized serving size used for this analysis is 8 oz serving (248 g). SDI was obtained from the Global Burden of Diseases study. Source data are provided as Source Data File 1. Centr/East Eur & Centr Asia Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, GDD Global Dietary Database, Latin Amer/Caribbean, Latin America/Caribbean, SDI sociodemographic development, SSB sugar-sweetened beverage, UI uncertainty interval.

Discussion

This analysis, based on new GDD estimates which incorporate data on 451 mostly national, individual-level dietary surveys, provides estimates of SSB intakes and trends between 1990 and 2018 globally, regionally, and nationally. In addition to updating previous 2010 estimates stratified by sex and age with additional surveys, modeling methods, and follow-up time19, we provide further estimates stratified by educational attainment and urbanicity. SSB intake is associated with a higher risk of obesity, CVD, T2D, cancer, and dental caries4,5,6, imposing important health and economic burdens. Many national guidelines recommend limiting SSBs and keeping added sugars to <5–10% of daily calories20,21,22. Our study can help inform national dietary guidance and SSBs policies, such as SSB taxes, warning labels, marketing standards, and nutrition education, as well as the need to focus on national subgroups with inequities in SSB intake such as younger adults globally, higher educated adults in Sub-Saharan Africa, and lower educated adults from Middle East/North Africa.

Despite all efforts worldwide, from 1990 to 2018, the global intake of SSBs increased by 16%, although the magnitude of increase decelerated in 2005–2018 compared with 1990–2005. However, the more recent global slowing, hides marked heterogeneity in regional trends, including the largest increase across all regions and time periods in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2005 to 2018 (+1.93, +41.4%) (Supplementary Data 2). Except for Latin America/Caribbean and High-Income Countries, all regions experienced steady increases in SSB intake between 1990 and 2018. Increasing trends were more pronounced in specific subnational groups, and with varying patterns in these groups by world region. For example, increases from 1990 to 2018 were larger among the youngest adults in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Middle East/North Africa, South East and East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa (Supplementary Table 15), while in other world regions, trends varied less by age. Trends were not notably different between males and females globally or regionally. Increases in intakes were higher in rural than in urban areas in Middle East/North Africa and Southeast and East Asia, but higher in urban than in rural areas in Sub-Saharan Africa and Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia. By education level (a proxy of socioeconomic status), increases in SSB intakes from 1990 to 2018 were greater among the lowest-educated adults in High-Income Countries, Middle East/North Africa, and Southeast and East Asia, but greater among the highest-educated adults in South Asia and the middle-educated adults in Sub-Saharan Africa. Based on these trends, by 2018 highest SSB intakes were among the highest educated adults globally and in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America/Caribbean (Table 1).

The inverse national correlation between SDI and SSB intake in 2018 (Fig. 8) represents cross-country comparisons of national development, as opposed to within-nation socioeconomic status of individuals. The SDI findings highlight cross-national inequities in intakes, showing that higher national social and economic development is statistically significantly correlated with lower SSB intakes. In comparison, within nations, socioeconomic status as measured by education has contrasting relationships with SSB intakes in different regions, with higher educated adults often consuming more SSBs in regions mostly composed of countries with lower SDI such as in Latin America/Caribbean, South Asia, and Sub-Sharan Africa (Fig. 5). These findings are in line with the ongoing nutrition and epidemiologic transition globally, disproportionally affecting the poorest nations23. Moreover, they indicate a need to accelerate strategies aimed at decreasing SSB intake to tackle this global health problem, focusing on key population groups within each specific world region.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has widely recommended SSBs taxes as one of the main evidence-based policy measures to reduce intake of SSBs24. Nevertheless, many of these efforts have been blunted by strong food industry opposition techniques including disqualification of research findings, biased industry-funded research, misleading summaries, marketing techniques, and false claims on the potential adverse social consequences such as massive job losses25,26. SSB taxes have been implemented in 108 nations globally, covering 52% of the world’s population, but most of these policies were implemented or updated after 2017 (n = 71, 66%)27, and thus their impact is mostly not captured in SSB intakes up to 2018. Future surveillance of SSB intakes globally is needed to determine the relative impact of these and other policies on SSB intakes (such as reformulation), both across nations and for subgroups within each nation.

With its economic growth and increasing middle class, Sub-Saharan Africa has become an appealing target for industry marketing of SSBs28. Despite evidence for the effectiveness of SSB taxes in South Africa, such measures have not been implemented in other countries in the region, limited by a lack of credible country-specific data and indicators on SSB intake to support the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of taxation29. The findings from our study may help inform SSB-related policies in these and other countries that may be lacking valid intake estimates. In addition, we found that SSB intakes in Sub-Saharan Africa among younger, more educated, and urban adults were among the highest in the world; and that these differences by socioeconomic characteristics were also more pronounced than in other regions. These results suggest that SSB policies directed at specific subgroups could have a large impact, supporting a more strategic allocation of limited public health resources in these nations.

While Latin America/Caribbean experienced the largest decrease in SSB intake after 1990, this region also had the highest SSB intake compared to all other regions in 1990, 2005, and 2018. Our findings further suggest no major differences by education level or area of residence, emphasizing the need for implementing broad policies to decrease SSBs across the general population. In recent years, several countries in this region have implemented policies targeting SSBs, including taxes, marketing restrictions, front-of-package warning labels, and education campaigns30. While SSBs taxes are recommended as one of the most effective measures24,31,32, only Chile (2014), Mexico (2014), Dominica (2015), Barbados (2015), Ecuador (2016), Peru (2018), Bermuda (2018), and Panama (2019), have implemented this policy (Supplementary Data 3)30. National sales analyses suggest moderate decreases in SSBs and increases in alternative beverages following implementation. In Mexico, for instance, SSB purchases decreased by 8.2% two years after tax implementation, with lower socioeconomic groups showing the largest decrease33. In Chile, household SSB purchases declined by 3.4% after the tax, with a higher impact among those with higher socioeconomic status34. Based on these successful but modest decreases, researchers and public health experts have advocated for higher tax rates and implementation across other nations to further impact SSB intakes25.

Most national measures to reduce SSB intakes have occurred relatively recently, limiting their impact during the period of our investigation. In Latin America, for example, regulations on the advertising of SSBs have been implemented in Brazil (2006), Mexico (2009), Peru (2013), and Chile (2016); evidence on the impact of these measures remains limited, particularly for adults30,35. Most recently, front-of-package “black box” warning labels for certain nutrients, including added sugars, have been implemented in several countries in Latin America. In Chile, an observational study of beverage purchases found that from 2015 to 2017 the purchase volume of SSBs decreased by 22.8 ml per capita (23.7%) after implementation of the labels36. The findings from our study demonstrating high intakes in this region add to the evidence that additional policies are needed aimed at decreasing SSBs. Given that most national SSB policies have been recently implemented, further surveillance in this region is essential to understand the effects of these programs, especially among population subgroups with the highest intakes. Our findings provide a foundation for future time-series analyses, carefully adjusted for other factors, to assess how these and other SSB-directed policies may relate to changes in within-country SSB intake over time.

A few national studies using mostly 24-hour recalls or food records found slightly lower estimates than GDD36,37. However, most of these defined SSBs only as soft drinks, which generally refers only to sodas or similar beverages, thus, excluding other SSBs such as energy drinks, fruit drinks (not 100%), and homemade sweetened beverages which were included in our estimates. Our findings might differ from estimates from sales data. However, the latter do not account for nonconsumption due to waste nor estimate a population “mean” due to the skewness of actual intakes.

We did not include sugar-sweetened milk, which are widely excluded from the definition of SSBs in policy and surveillance; nor home-sweetened teas or coffees (which often would have less than 50 kcal/serving). Home-sweetened teas and coffees were not explicitly excluded from the SSBs definition when data was requested from data owners. However, these were most likely excluded by the data owners in the majority of the cases given that tea and coffee were collected as separate variables within the same data request. Global dietary surveys generally do not collect information on sweetened tea or coffee, and even sales data on ready-to-drink tea and coffee is limited. Therefore, by excluding these products we enhance comparability across countries and findings from other reports. Furthermore, sales data suggest that ready-to-drink (RTD) tea consumption was relatively modest in Asia in 2018 (0.33 8-oz servings/week), showing slight growth in comparison to 201438. Thus, the inclusion of these teas would not substantially alter our results. However, the Asian market for RTD teas, along with coffees, is expanding, and future surveillance and monitoring of the intake is needed to keep pace with this evolving category. Although fruit juices (100%) contain free sugars, observational analyses suggest no major associations of 100% fruit juice with key disease outcomes39,40. Therefore, these were excluded from our definition of SSBs, which focuses on beverages with added sugar.

Our definition may have missed beverages with lower sugar content, but the vast majority were captured. For instance, the calorie content per 8 oz serving is typically between 84 to 104 calories for regular sodas, 106 to 154 calories for energy drinks, 114 to 134 for juice drinks, and 114 to 216 for “aguas frescas”. As a result, our definition encompasses all usual SSBs and even some with less sugar than average.

The WHO recommends limiting the intake of added sugars to less than 10% of the total caloric intake, with additional benefits at intakes lower than 5%22. Our findings on high intakes of SSBs and increases over time across most regions, support the global actions aimed at decreasing the intake of SSBs such as taxes. Moreover, this highlights the need to target all sugar-containing beverages, including sweetened teas and milk, to prevent substitution with these beverages.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, our investigation is the first to assess and report global, regional, and national estimates of SSB intakes jointly stratified by age, sex, education, and urbanicity. Compared to previous estimates, our current model included a larger number of dietary surveys, additional demographic subgroups, and years of assessment. Updated Bayesian hierarchical models better incorporated survey and country-level covariates; assessed time trends; and addressed heterogeneity, missingness, and sampling and modeling uncertainty. Intakes were estimated from 451 surveys, mostly nationally or subnationally representative, collected at the individual-level, and representing 87.1% of the world’s population. Other recent estimates of global SSBs relied mostly on national per capita estimates of food availability (e.g. FAO food balance sheets) or sales data41. Such findings can substantially misestimate intake compared to individual-level data42 and are less robust for characterizing differences across population subgroups. Our estimates are informed by individual-level dietary data collected from both 24-hour recalls (24% of surveys), a gold standard for assessing nutritional intake of populations, and food frequency questionnaires (61% of surveys), a validated approach for measuring SSB intakes43,44 (Supplementary Table 4). Finally, our findings are consistent with individual national reports45, such as in Mexico where urban vs. rural residents and those with higher vs. lower socioeconomic status had higher SSB intakes46; with the opposite in the US47, (Supplementary Table 6).

Even with systematic searches for all relevant surveys, we identified limited availability for several countries (particularly lower-income nations) and time periods48. Thus, estimated findings in countries with no primary individual-level surveys have higher corresponding uncertainty, informing surveillance needs to assess SSBs nationally and in subnational populations. Particularly, there were limited surveys identified for South Asia (n = 9) and Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 22), which might have limited the accuracy of our estimates in those regions (Supplementary Table 4). All types of dietary assessments include some error, whether from individual-level surveys, national food availability estimates, or other sources. Our model’s incorporation of multiple types and sources of dietary assessments provides the best available estimates of global diets, as well as the uncertainty of these estimates. For instance, self-reported data relies on the memory and personal biases of the respondents, thus introducing potential bias in their responses by under or overreporting their actual intakes. Furthermore, assumptions relating to standardization of serving sizes, SSB definitions, energy adjustment, and household-level disaggregation, as well as of no interaction between sociodemographic variables in our model, could have impacted our estimates. We decided not to include interaction terms between various demographic variables to preserve model stability. To minimize these limitations, we used standardized approaches and carefully documented each survey’s methods and standardization processes to maximize transparency. Overall, our findings should be taken as the best currently available, but still imperfect, estimates of SSB intake worldwide.

In conclusion, our estimates of SSB intakes reveal that the global intakes increased by 16% from 1990 to 2018, with large heterogeneity by world region and population characteristics. Our findings also provide evidence on national and subnational SSB intakes, trends over time, and related nutritional inequities, helping to inform the need and design of national and more targeted policies and approaches to reduce SSB intake worldwide, highlighting the growing problem of SSBs for public health in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Ethics and inclusion statement

Data informing the GDD modeling estimates for this study, including from LMICs, were collected between 1980 and 2020 in the form of dietary intake surveys. If nationally representative surveys were not available for a country, we also considered national surveys without representative sampling, followed by regional, urban, or rural surveys, and finally large local cohorts, provided that selection and measurement biases were not apparent limitations. For countries with no surveys identified, other sources of potential data were considered, including the WHO Infobase, the STEP database, and household budget survey data. As of August 2021, we identified and retrieved 1634 eligible survey years of data from public and private sources. Of these, 1225 have been checked, standardized, and approved for GDD 2018 model inclusion, of which 451 surveys inform the SSB intake estimates. Most identified data were either privately held or not in a format appropriate for our modeling. We thus relied almost entirely on direct author contacts in each country to provide us with exposure data directly. The roles and responsibilities of GDD Consortium members were determined and agreed upon before data sharing as part of a standardized data-sharing agreement.

The draft manuscript was shared with all GDD consortium members before submission for peer review, and all members have been included as authors of this work. We endorse the Nature Portfolio journals’ guidance on LMIC authorship and inclusion and are committed to the inclusion of researchers from LMICs in publications from the GDD. We share the GDD data with the entire consortium, encourage authors from LMICs to take the lead on analyses and papers, and provide technical and writing support to LMIC authors. For more details on the collaborative GDD data-collection process, please visit our website at https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/methods/summary-methods-and-data-collection. This research is locally relevant to all countries included, given that it disaggregates findings nationally and subnationally by key demographic factors such as age, sex, education level, and urbanicity, providing decision-makers with stratum-specific SSB intake data and trends over time. This investigation was exempt from ethical review board approval because it was based on published de-identified nationally representative data, without personally identifiable information. Individual surveys underwent ethical review board approval required for the applicable local context.

Study design

This investigation is based on a serial cross-sectional analysis of SSB intakes from the GDD 2018 for 185 countries. The GDD is an international collaborative effort to produce comprehensive and comparable estimates of dietary intakes of major foods and nutrients in 185 countries. Details on the methods and standardized data-collection protocol have been described previously and are also explained below19,48,49,50,51,52,53. Compared to GDD 2010, innovations include a major expansion of individual-level dietary surveys and global coverage through 2018; inclusion of updated data jointly stratified subnationally by age, sex, education level, and urban or rural residence; and updated modeling methods, covariates, and validation to improve estimates of stratum-specific mean intakes and uncertainty. This present analysis focuses on findings for adults aged 20+ years.

Data sources

The approach and results of our survey search strategy by dietary factor, time, and region have been detailed elsewhere48. Briefly, we performed systematic online searches for individual-level dietary surveys in countries globally, as well as extensive personal communications with researchers and government authorities throughout the world, inviting them to be corresponding members of the GDD. Surveys were prioritized if nationally or subnationally representative and using individual-level dietary assessments with standardized 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires, or short standardized questionnaires (e.g., Demographic Health Survey questionnaires). When national or subnational individual-level surveys were not identified for a country, we searched for individual-level surveys from large cohorts, the WHO Global Infobase, and the WHO Stepwise Approach to Surveillance database. Household budget surveys were used when individual-level dietary surveys were not identified for a particular country. We excluded surveys focused on special populations (e.g., exclusively pregnant or nursing women, individuals with a specific disease) or cohorts (e.g., specific occupations or dietary patterns). The final GDD model incorporated 1225 dietary surveys representing 185 countries and 99.0% of the global population in 2018. Of these, 451 surveys reported data on SSBs, totaling 2.9 million individuals from 118 countries representing 87.1% of the global population (Supplementary Tables 4–5).

Most surveys were nationally or subnationally representative (94.2%), collected at the individual level (84.7%), and included estimates in, both urban and rural areas of residence (61.6%). The total sample size included 44.3% female and 55.7% male; 70% participants from urban and 30% participants from rural areas of residence; 16.0%, 37.6%, and 46.4% participants with low, medium, and high education respectively; and 53.2% adults (18+ years) and 46.8% children/adolescents (<18 years). Further details on survey characteristics are in Supplementary Data 1.

Data extraction

For each survey, we extracted data using standardized methods on survey characteristics and dietary metrics, units, mean, and standard deviation of intake, by age, sex, education level, and urban or rural residence52,53. The sociodemographic characteristics were used as reported by each survey, and details on whether these were self-reported or measured in any other way are unavailable. Data were assessed for extraction errors and for plausibility using standardized algorithms, and survey quality by evaluating evidence for selection bias, sample representativeness, response rate, and validity of the diet assessment method (Supplementary Methods S1). Measurement comparability across surveys was maximized by using a standardized data analysis approach including averaging all days of dietary assessment to quantify mean individual-level intakes; using harmonized dietary factor definitions and units of measure across surveys; and adjusting for total energy through the residual method and using age-specific energy intakes to reduce measurement error and account for regional differences in body size, metabolic efficiency, and physical activity. All intakes are reported adjusted to 2000 kcal/day for ages 20–74 years, and 1700 kcal/day for ages 75+ years. The adult male equivalent (AME) method was used for 15 household-level surveys (3.3% of all surveys) to convert the household data to individual data based on energy requirements for a specific age and sex (Supplementary Methods 1). SSBs were defined based on their caloric content as any beverages with added sugars (as identified by product name) and ≥50 kcal per 8 oz (236.5 grams) serving, including commercial or homemade beverages, soft drinks, energy drinks, fruit drinks, punch, lemonade, and aguas frescas. This definition excluded 100% fruit and vegetable juices, non-caloric artificially sweetened drinks, and sweetened milk. All included surveys used this definition.

Data modeling

Our model estimates intakes for years for which we have survey data available. To incorporate and address differences in data comparability and sampling uncertainty, a Bayesian model with a nested hierarchical structure (with random effects by country, region, and globally) estimated the mean consumption level of SSBs and its statistical uncertainty for each of 264 population strata across 185 countries for 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 201853. Although this analysis focuses only on adults aged 20+ years, the model used all age data to generate the strata estimates.

Primary inputs were the survey-level quantitative data on SSB intakes (by country, time, age, sex, education level, and urban or rural residence); survey characteristics (dietary assessment method, type of dietary metric); and country-year-specific covariates (Supplementary Methods 2). The model included overdispersion of survey-level variance for surveys that were not nationally representative or not stratified by smaller age groups (≤10 years), sex, education level, or urbanicity. The model then estimated intakes jointly stratified by age (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94, 95+ years), sex (female, male), education (≤6 years of education, >6 years to 12 years, >12 years), and urbanicity (urban, rural). Uncertainty of each stratum-specific estimate was quantified using 4000 iterations to determine posterior distributions of mean intake jointly by country, year, and sociodemographic subgroup. We computed the median intake and the 95% uncertainty interval (UI) for each stratum as the 50th, 2.5th, and 97.5th percentiles of the 4000 draws, respectively. We evaluated multiple different estimation models, and the best model was selected using five-fold cross-validation (randomly omitting 20% of the raw survey data, run five times) and validity was further assessed by comparing predicted vs. observed intakes, excluding implausible estimates (Supplementary Table 2), and by visual assessment of global and national mean intakes using heat maps. A second Bayesian model was used to strengthen time trend estimates for dietary factors with corresponding food or nutrient availability data from FAO Food Balance Sheets54 or the Global Expanded Nutrient Supply55.

The model incorporated country-level intercepts and slopes from these covariates, along with their correlation estimated across countries. No time component was formally included in the model; rather, time was captured by the underlying time variation in the model covariates. This model is commonly referred to as a varying slopes model structure and leverages two-dimensional partial pooling between intercepts and slopes to regularize all parameters and minimize overfitting risk56,57. The final presented results are a combination of these two Bayesian models, as detailed in Supplementary Methods 3.

Statistical analysis

Global, regional, national, and within-country population subgroup intakes of SSBs and their uncertainty were calculated as population-weighted averages using all 4000 posterior estimates for each of the 264 demographic strata in each country year. Population weights for each year were derived from the United Nations Population Division58, supplemented with data for education and urban or rural status from Barro and Lee59 and the United Nations60. For the present analysis, GDD SSB estimates were collapsed for adults aged 85+ years using the 4000 simulations corresponding to the stratum level intake data derived from the Bayesian model.

Intakes were calculated as 8 oz (248 grams) servings per week. For the original SSBs definition data was requested as servings of 8 oz = 236.5 grams (Supplementary Table 1). However, for this analysis, we used the conversion 8 oz = 248 grams consistent with what has been reported in FoodData Central by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service as the equivalence for SSBs61. Absolute changes and percentage changes in consumption between 1990, 2005, and 2018 were calculated at the stratum-specific level using all 4000 posterior estimates to account for the full spectrum of uncertainty and standardized to the proportion of individuals within each stratum in 2018 to account for changes in demographics over time. Stratum-specific estimates were summed to calculate the differences in intake in males vs. females, high (>12 years) vs. low (≤6 years) education, and urban vs. rural residence, further stratified by sex, age, education, and area of residence as appropriate.

We also assessed the correlation between country-level SSB intakes and the corresponding national sociodemographic development index (SDI), and how these relationships changed over time between 1990, 2005, and 2018. SDI is a measure of country/region development, ranging from 0 to 1, based on incomes per capita, average educational attainment, and fertility rates62. For comparisons between groups (or over time), difference thresholds were regarded as significant if the 95% UI of the difference (or change over time) did not include zero. Given the Bayesian statistical framework of our estimates, rather than frequentist null hypothesis significance testing, no p-value should be defined for statistical significance and 95% UIs of each estimate should be considered a guide63.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The individual SSB intake estimate distribution data used in this as means and uncertainty (SE) for each strata in the analysis are available freely online at the Global Dietary Database (GDD, Download 2018 Final Estimates: https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/data-download). GDD data were utilized in agreement with the database guidelines. GDD data collapsed for 85+ and by age categories 20–39, 40–59, and 60+, as well as the absolute and relative differences by strata and by year presented in this analysis, were calculated using the 4000 simulations corresponding to the stratum level intake data derived from the Bayesian model. The derived source data are provided with this paper. The 4000 simulations files can be made available to researchers upon request. Eligibility criteria for such requests include utilization for nonprofit purposes only, for appropriate scientific use based on a robust research plan, and by investigators from an academic institution. If you are interested in requesting access to the data, please submit the following documents: (1) proposed research plan (please download and complete the proposed research plan form: https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/sites/default/files/manual_upload/research-proposal-template.pdf), (2) data-sharing agreement (please download this form https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/sites/default/files/manual_upload/tufts-gdd-data-sharing-agreement.docx and complete the highlighted fields, have someone who is authorized to enter your institution into a binding legal agreement with outside institutions sign the document. Note that this agreement does not apply when protected health information or personally identifiable information are shared), (3) email items (1) and (2) to info@globaldietarydatabase.org. Please use the subject line “GDD Code Access Request”. Once all documents have been received, the GDD team will be in contact with you within 2–4 weeks regarding subsequent steps. Data will be shared as.csv or.xlsx files, using a compressed format when appropriate. Population weights for each strata and year were derived from the United Nations Population Division (https://population.un.org/wpp/), supplemented with data for education and urban or rural status from Barro (DOI: 0.3386/w15902) and Lee and the United Nations (https://population.un.org/wup/Download/). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom code was developed using R (Version 4.0.0) for analyzing the data including aggregation of the 4000 simulations to the desired strata categories, calculation of absolute and relative differences, and summary of mean intakes globally, regionally, and nationally jointly stratified by sociodemographic group, and data visualizations including tables and figures. Given the computational size, the data aggregation, calculation of absolute and relative differences, and summary of mean intakes were run on the Tufts University High-Performance Computing Cluster (https://it.tufts.edu/high-performance-computing), supported by the National Science Foundation (grant:2018149) under active development by Research Technology, Tufts Technology Services. The statistical code can be made available to researchers upon request. Eligibility criteria for such requests include utilization for nonprofit purposes only, for appropriate scientific use based on a robust research plan, and by investigators from an academic institution. GDD will nominate co-authors to be included in any papers generated using GDD-generated statistical code. If you are interested in requesting access to the statistical code, please submit the following documents: (1) proposed research plan (please download and complete the proposed research plan form: https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/sites/default/files/manual_upload/research-proposal-template.pdf), (2) data-sharing agreement (please download this form https://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/sites/default/files/manual_upload/tufts-gdd-data-sharing-agreement.docx and complete the highlighted fields, have someone who is authorized to enter your institution into a binding legal agreement with outside institutions sign the document. Note that this agreement does not apply when protected health information or personally identifiable information are shared), (3) email items (1) and (2) to info@globaldietarydatabase.org. Please use the subject line “GDD Code Access Request”. Once all documents have been received, the GDD team will be in contact with you within 2–4 weeks regarding subsequent steps. Data will be shared as.csv or.xlsx files, using a compressed format when appropriate.

References

Klemm, S. Ethics: health equity and dietetics-related inequalities. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 122, 1558–1562 (2022).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249 (2020).

O’Hearn, M., Liu, J., Cudhea, F., Micha, R. & Mozaffarian, D. Coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalizations attributable to cardiometabolic conditions in the United States: a comparative risk assessment analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e019259 (2021).

Singh, G. M. et al. Estimated global, regional, and national disease burdens related to sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in 2010. Circulation 132, 639–666 (2015).

Malik, V. S. & Hu, F. B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 205–218 (2022).

Bleich, S. N. & Vercammen, K. A. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obes. 5, 6 (2018).

Malik, V. S. & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health: an update of the evidence. Nutrients 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081840 (2019).

Houghtaling, B. et al. A rapid review of stocking and marketing practices used to sell sugar-sweetened beverages in U.S. food stores. Obes. Rev. 22, e13179 (2021).

Dowling, E. A., Roberts, C., Adjoian, T., Farley, S. M. & Dannefer, R. Disparities in sugary drink advertising on New York City streets. Am. J. Prev. Med 58, e87–e95 (2020).

Marriott, B. P., Hunt, K. J., Malek, A. M. & Newman, J. C. Trends in intake of energy and total sugar from sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States among children and adults, NHANES 2003-2016. Nutrients 11, 2004 (2019).

Della Corte, K. et al. World trends in sugar-sweetened beverage and dietary sugar intakes in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 79, 274–288 (2021).

Dawes, E., D’Onise, K. & Spurrier, N. Trends in soft drink and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among South Australians, focusing on distribution of intake by subpopulation. Aust. N.Z.J. Public Health 44, 410–418 (2020).

Morgan, K. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption from 1998-2017: Findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children/school health research network in Wales. PLoS One 16, e0248847 (2021).

Jones, A. C., Kirkpatrick, S. I. & Hammond, D. Beverage consumption and energy intake among Canadians: analyses of 2004 and 2015 national dietary intake data. Nutr. J. 18, 60 (2019).

Holstein, B. E. et al. Intake of sugar sweetened soft drinks among adolescents: trends and social inequality in Denmark 2002-2018. Nutr. Health 26, 3–8 (2020).

Figueiredo, N., Maia, E. G., Silva, L., Granado, F. S. & Claro, R. M. Trends in sweetened beverages consumption among adults in the Brazilian capitals, 2007-2016. Public Health Nutr. 21, 3307–3317 (2018).

Hwang, S. B. et al. Trends in beverage consumption and related demographic factors and obesity among korean children and adolescents. Nutrients 12, 2651 (2020).

Gulati, S. & Misra, A. Sugar intake, obesity, and diabetes in India. Nutrients 6, 5955–5974 (2014).

Singh, G. M. et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: a systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS One 10, e0124845 (2015).

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of health and human services. dietary guidelines for americans, 2020–2025. (2020).

American Heart Association (AHA). Added Sugars, https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/added-sugars (2021).

World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. (Geneva, Switzerland, 2015).

Popkin, B. M. & Ng, S. W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. 23, e13366 (2022).

World Health Organization. WHO Manual on sugar-sweetened beverage taxation policies to promote healthy diets. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2022).

Fooks, G. J., Williams, S., Box, G. & Sacks, G. Corporations’ use and misuse of evidence to influence health policy: a case study of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation. Glob. Health 15, 56 (2019).

Pedroza-Tobias, A., Crosbie, E., Mialon, M., Carriedo, A. & Schmidt, L. A. Food and beverage industry interference in science and policy: efforts to block soda tax implementation in Mexico and prevent international diffusion. BMJ Glob. Health 6 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005662 (2021).

World Bank Group. Global SSB Tax Database, https://ssbtax.worldbank.org/ (2023).

Audain, K., Levy, L. & Ellahi, B. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the early years and implications for type-2 diabetes: a sub-Saharan Africa context. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 78, 547–553 (2019).

Erzse, A. et al. The data availability landscape in seven sub-Saharan African countries and its role in strengthening sugar-sweetened beverage taxation. Glob. Health Action 14, 1871189 (2021).

Bergallo, P., Castagnari, V., Fernández, A. & Mejía, R. Regulatory initiatives to reduce sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in Latin America. PLoS One 13, e0205694 (2018).

World Health Organization (WHO). Fiscal policies to promote healthy diets: policy brief. (2022).

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation in the Region of the Americas. (Washington, D.C., 2020).

Colchero, M. A., Rivera-Dommarco, J., Popkin, B. M. & Ng, S. W. In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Health Aff. 36, 564–571 (2017).

Caro, J. C. et al. Chile’s 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax and changes in prices and purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages: an observational study in an urban environment. PLoS Med. 15, e1002597 (2018).

Correa, T. et al. Responses to the Chilean law of food labeling and advertising: exploring knowledge, perceptions and behaviors of mothers of young children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 16, 21 (2019).

Taillie, L. S., Reyes, M., Colchero, M. A., Popkin, B. & Corvalán, C. An evaluation of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: a before-and-after study. PLOS Med. 17, e1003015 (2020).

Walton, J. & Wittekind, A. Soft drink intake in Europe: a review of data from nationally representative food consumption surveys. Nutrients 15, 1368 (2023).

Statista. Ready-to-Drink (RTD) Tea - Worldwide https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/non-alcoholic-drinks/ready-to-drink-rtd-coffee-tea/ready-to-drink-rtd-tea/worldwide.

Imamura, F. et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 351, h3576 (2015).

Miller, V. et al. Evaluation of the quality of evidence of the association of foods and nutrients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2146705–e2146705 (2022).

Beal, T., Herforth, A., Sundberg, S., Hess, S. Y. & Neufeld, L. M. Differences in modelled estimates of global dietary intake. Lancet 397, 1708–1709 (2021).

Del Gobbo, L. C. et al. Assessing global dietary habits: a comparison of national estimates from the FAO and the global dietary database. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 1038–1046 (2015).

Willett, W. Nutritional Epidemiology. (Oxford Scholarship Online, 2012).

Vanderlee, L. et al. Evaluation of the online beverage frequency questionnaire (BFQ). Nutr. J. 17, 73 (2018).

Noncommunicable Disease Control Programme. Technical report on: Policy options for taxing sugar-sweetened beverages in Bangladesh. (Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 2021).

Sánchez-Pimienta, T. G., Batis, C., Lutter, C. K. & Rivera, J. A. Sugar-sweetened beverages are the main sources of added sugar intake in the Mexican population. J. Nutr. 146, 1888S–1896S (2016).

Zagorsky, J. L. & Smith, P. K. Who drinks soda pop? Economic status and adult consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Econ. Hum. Biol. 38, 100888 (2020).

Miller, V. et al. Global Dietary Database 2017: data availability and gaps on 54 major foods, beverages and nutrients among 5.6 million children and adults from 1220 surveys worldwide. BMJ Glob. Health 6, e003585 (2021).

Powles, J. et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 3, e003733 (2013).

Micha, R. et al. Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 348, g2272 (2014).

Micha, R. et al. Global, regional and national consumption of major food groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 5, e008705 (2015).

Micha, R. et al. Estimating the global and regional burden of suboptimal nutrition on chronic disease: methods and inputs to the analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 119–129 (2012).

Miller, V. et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of animal-source foods between 1990 and 2018: findings from the Global Dietary Database. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e243–e256 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food balances. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (2021).

Smith, M. R., Micha, R., Golden, C. D., Mozaffarian, D. & Myers, S. S. Global expanded nutrient supply (GENuS) model: a new method for estimating the global dietary supply of nutrients. PLoS One 11, e0146976 (2016).

Gelman, A. & Pardoe, I. Bayesian measures of explained variance and pooling in multilevel (Hierarchical) models. Technometrics 48, 241–251 (2006).

Wagner, T., Diefenbach, D. R., Christensen, S. & Norton, A. S. Using multilevel models to quantify heterogeneity in resource selection. J. Wildl. Manag. 75, 1788–1796 (2011).

United Nations Population Division. Total population by sex (Thousands). https://population.un.org/wpp/ (2019).

Barro, R. & Lee, J. A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950–2010. J. Dev. Econ. 104, 184–198 (2013).

United Nations Population Division. Urban population (% of Total Population). https://population.un.org/wup/Download/ (2018).

U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central, https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (2019).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Seattle, United States of America, 2020).

Kruschke, J. K. & Liddell, T. M. The Bayesian new statistics: hypothesis testing, estimation, meta-analysis, and power analysis from a Bayesian perspective. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 178–206 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Gates Foundation (grant OPP1176682 to D.M.), the American Heart Association (grant 903679 to L.L.C), and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología in Mexico (to L.L.C.). We acknowledge the Tufts University High-Performance Computing Cluster (https://it.tufts.edu/high-performance-computing), which was used for the research reported in this paper. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 2018149. The computational resource is under active development by Research Technology, Tufts Technology Services. The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.C, R.M. and D.M.; methodology, L.L.C, R.M., D.M. and S.B.C.; software, F.C., P.S., J.Z., J.M., V.M. and L.L.C.; validation, L.L.C., R.M. and D.M.; formal analysis, L.L.C.; investigation, L.L.C.; data curation, F.C., P.S., J.Z., V.M., J.R.S. and L.L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.C.; writing, review and editing, L.L.C., R.M., D.M. and S.B.C.; visualization, L.L.C., R.M., D.M., V.M. and S.B.C.; supervision, D.M., R.M. and S.B.C.; project administration, D.M.; funding acquisition, D.M., R.M., L.L.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The investigators did not receive funding from a pharmaceutical company or other agency to write this report. L.L.C reports research funding from the Gates Foundation, the American Heart Association, and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología in Mexico, outside of the submitted work. R.M. reports research funding from the Gates Foundation; and (ended) the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Danone, and Nestle. She also reports consulting from Development Initiatives and as IEG chair for the Global Nutrition Report, outside of the submitted work. F.C., J.Z., and P.S. report research funding from the Gates Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health, outside of the submitted work. V.M. reports research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and from the American Heart Association, outside the submitted work. J.R.S. reports research funding from the Gates Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health, Nestlé, Rockefeller Foundation, and Kaiser Permanent Fund at East Bay Community Foundation, outside of the submitted work. S.B.C. reports research funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Rockefeller Foundation, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation, outside the submitted work. D.M. reports research funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Vail Innovative Global Research, and the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation; personal fees from Acasti Pharma, Barilla, Danone and Motif FoodWorks; is on the scientific advisory board for Beren Therapeutics, Brightseed, Calibrate, Elysium Health, Filtricine, HumanCo, Instacart, January Inc., Perfect Day, Tiny Organics, and (ended) Day Two, Discern Dx, and Season Health; has stock ownership in Calibrate and HumanCo; and receives chapter royalties from UpToDate, all outside the submitted work. J.E.M. declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks James Bentham, Anette Buyken, and Lindsey Smith Taillie for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lara-Castor, L., Micha, R., Cudhea, F. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage intakes among adults between 1990 and 2018 in 185 countries. Nat Commun 14, 5957 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41269-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41269-8

This article is cited by

-

Determinants of obesity in Latin America

Nature Metabolism (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.