Abstract

Sterically congested C–O and C–N bonds are ubiquitous in natural products, pharmaceuticals, and bioactive compounds. However, the development of a general method for the efficient construction of those sterically demanding covalent bonds still remains a formidable challenge. Herein, a photoredox-driven ring-opening C(sp3)–heteroatom bond formation of arylcyclopropanes is presented, which enables the construction of structurally diversified while sterically congested dialkyl ether, alkyl ester, alcohol, amine, chloride/fluoride, azide and also thiocyanate derivatives. The selective single electron oxidation of aryl motif associated with the thermodynamic driving force from ring strain-release is the key for this transformation. By this synergistic activation mode, C–C bond cleavage of otherwise inert cyclopropane framework is successfully unlocked. Further mechanistic and computational studies disclose a complete stereoinversion upon nucleophilic attack, thus proving a concerted SN2-type ring-opening functionalization manifold, while the regioselectivity is subjected to an orbital control scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

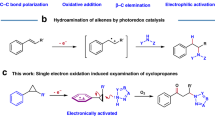

C(sp3)–heteroatom bond construction represents one of the fundamental operations which finds a wide application in pharmaceutical relevant research, material science and agrochemical development, among others1. In particular, the assembly of sterically congested ethers/amines are of intense interests. However, conventional methods to access these targets always faces daunting challenges2. While the venerable SN2 reactions as exemplified by Williamson ether synthesis3,4 and Mitsunobu reaction5,6 are virtually straightforward, they are, however, heavily restricted to primary and secondary alkyl electrophiles. The synthetic elaboration of tertiary congener still remains problematic in modern synthetic organic chemistry because of the intrinsic reaction nature (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, the SN1 reactions which traverse through carbocation species often lead to stereoablative transformation, although they are relatively insensitive to steric encumbrance because of the flattened reaction intermediates involved (Fig. 1a)7,8,9,10. More recently, by taking advantage of a controlled generation of carbocation intermediate from electro- or photo-catalyzed decarboxylation, Baran11 and Nagao/Ohmiya’s12,13 groups achieved efficient synthesis of sterically-hindered dialkyl ethers. Despite these advancements, the development of new strategies that encompass the merits of both SN2 (for stereochemistry transfer) and SN1 reactions (for steric insusceptibility) would be of undeniable significance.

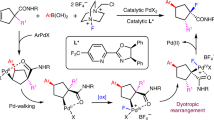

Specifically, nucleophilic displacement for forging tert-C(sp3)–heteroatom linkage is made possible by either leveraging electronically activated substrates such as tertiary electrophiles bearing electron-withdrawing groups (the reaction mode varies depending on respective catalytic regimes, through either quasi-SN214,15,16,17,18, or metal-promoted stereoconvergent coupling manifold19,20,21,22,23,24,25) or utilizing bespoke precursors for entropically more favored intramolecular annulations. For example, an elegant work from Cook and co-workers has revealed that intramolecular substitution of tertiary alcohol for cyclic sulfonamide synthesis could be readily accomplished by employing iron salt as Lewis acidic catalyst26,27. The chirality transfer of enantioenriched alcohols was rationalized by a stereoinvertive displacement involving tight-ion pairs (Fig. 1b). As an alternative, by harnessing ring-strain release28,29,30,31, small heterocycles such as epoxide and aziridine could also readily participate in nucleophilic displacement of those strained C–N/O bond32,33. However, the ring-opening cleavage of C–C bond embedded in small carbocycles such as cyclopropane is relatively underexplored except for those electronically biased donor-acceptor ones34,35,36,37. Recently, a strain-release-driven stereoinvertive ring-opening substitution of cyclopropyl carbinol derivatives was accomplished by Marek and coworkers (Fig. 1c)38. Also of note, a pioneering work of ring-opening etherification of arylcyclopropane enabled by ultraviolet light sensitization was disclosed by Rao and Hixson39. Further mechanistic study by Dinnocenzo et al. confirmed the involvement of a cyclopropane radical cation intermediate and a three-electron SN2-like pathway40,41. However, the harsh conditions and use of specific apparatus undoubtedly limit its broader synthetic application. In 2019, our group reported a visible light-promoted oxo-amination of aryl cyclopropanes using nitrogen-containing heterocycles as the nucleophiles under aerobic conditions42. By capitalizing on a similar ring-opening strategy, elegant works from Studer and co-workers further enabled 1,3-difunctionalization of arylcyclopropanes under photoredox or cooperative NHC/photoredox catalysis43,44. In addition, by resorting to electrocatalysis, Werz et al. have realized a facile ring-opening functionalization of donor–acceptor cyclopropane/cyclobutane45,46.

While notable progress has been attained during the past several years, the underlying problems such as harsh reaction conditions, limited substrate generality, employment of hazardous reagents are still of big concern. Therefore, the development of novel protocols that encompass wide substrate scope and mild reaction conditions without using strong base/acid, extra oxidant/reductant is still highly desirable. With our continuing interest in developing strategically novel synthetic transformation with photoredox catalysis42,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, here we report a protocol for the construction of sterically congested C(sp3)–heteroatom bonds via ring opening functionalization of electronically unbiased aryl cyclopropanes (Fig. 1d). Notable features of the present strategy include: i) selective SET-oxidation enables the smooth generation of aryl cation radial intermediate54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, which engenders a remote activation of cyclopropane skeleton through σ to SOMO orbital interaction49,50,64; ii) the synergistic substrate activation (via intentional generation of donor-acceptor cyclopropane cation radical intermediate34,35,36,37) and strain-release enables a stereoselective SN2-like interaction with relatively weak nucleophile under essentially neutral reaction conditions; iii) the integration of SET process and hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) event enables a redox-neutral transformation; iv) a LUMO orbital coefficient distribution controlled regioselectivity was proposed, which is supported by DFT calculation.

Results

Reaction optimization

Based on the cyclic voltammetry measurement of aryl cyclopropane substrate 1 (E1/2ox = +1.30 V vs. saturated calomel electrode in MeCN)42, the model reaction between 1 and trifluoromethanesulfonamide (TfNH2) was attempted with selected photocatalysts (PC-I to PC-IX) under N2 atmosphere. After extensive investigation of reaction parameters (selected conditions were listed in Table 1, for detailed condition optimization, see Supplementary Methods), we were pleased to find that under the irradiation of blue LEDs while using acridinium series as photocatalyst and diphenyl disulfide as the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reagent, the model reaction conducted in DCE provided the desired product 2 in moderate to good yields (Table 1, entries 1–9)65,66. Among these, the PC-VIII (E1/2(Acr*/Acr-) = +2.08 V vs. SCE)67 proved to be the best, which afforded product 2 in 86% yield (entries 8). Further fine tuning of the reaction parameters eventually led to the formation of product 2 in 91% yield (entries 10). Negative control experiments clearly demonstrated the critical role of photocatalyst, light irradiation and nitrogen atmosphere in the present transformation (entries 11–12). Pleasingly, the optimal reaction condition for amination was also well suited for sterically hindered ether construction simply using alcohol as the nucleophile, and in the case of ethyloxylation reaction the desired product 3 could be readily obtained in 92% yield (entries 13). It is worth pointing out that all these nucleophilic ring-opening reactions occurred in a highly regioselective manner without any regioisomers derived from nucleophilic attack at methylene or methine carbon atoms being observed.

Examination of substrate scope

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the substrate scope with respect to arylcyclopropane was investigated using ethanol, TfNH2 and pyrazole as nucleophiles (Fig. 2). It was found that cyclopropanes with electron-donating groups on the phenyl ring, such as methoxyl, alkyl, and phenyl reacted smoothly and provided the ethyl ethers (3–5, 7), amides (2, 28, 30, 32) and α-quaternary substituted heterocycles (27, 29) in good yields, respectively. Moreover, polycyclic aromatic cyclopropane was also viable substrate as showcased by examples of 8 and 33, though somewhat diminished reaction efficiency was observed in the latter case. When using unsubstituted phenyl cyclopropane with higher oxidation potential, the desired products could still be obtained in acceptable yields (6, 31), albeit requiring prolonged reaction time. Then the influence of the alkyl substituents on cyclopropyl ring system was examined. Changing the gem-dimethyl into bulkier gem-diethyl group had no obvious impediment on this reaction, and the etherification product 9 could be obtained in 95% yield, whereas 4-methoxyphenyl cyclopropane without alkyl substituent reacted sluggishly, leading to 26% yield of 37 in amination reaction. These contrasting experiments indicated that the steric demanding substituents on cyclopropane are not detrimental but conducive to the ring-opening cleavage, which could be rationalized by more effective positive charge delocalization as well as thermodynamically more favored ring-strain release. Spirocyclic substrates with differing ring size were proved amenable to this reaction, providing the desired cycloalkyl ether (10–12) and amine (34–36) derivatives in good yields. Furthermore, 1,2-arylalkyl-substituted cyclopropanes were also viable substrates irrespective of the stereochemistry, and remote functional groups, such as ester, aryl were well tolerated (38, 13–14). In these cases, excellent regioselectivities were still observed with nucleophiles attacking the alkyl-substituent carbon atom. It is also of note, cyclopropylamine derivatives were enabling substrates, which participated in ring-opening substitution reactions uneventfully to afford respective aminal products (15–17, 39–41). Additionally, 1,2-diaryl cyclopropanes were also revealed to be applicable (18–20, 42–45). When unsymmetric substrates were employed, the nucleophilic attack happened on the carbon atom containing more electron-rich aryl substituent with high to excellent regioselectivity (19, 20, 43–45). This unusual selectivity was further interpreted by DFT calculation (vide infra). The same principle was also applicable to the 1,2,3-triaryl substituted substrate, which secured a highly selective transformation (25). In the case of benzo-fused tricyclic substrates, the reaction occurred smoothly to generate ring-expansion products (21, 22, 46, 47), whereas for aryl-substituted bicyclic substrates the reaction happened selectively to afford trans-products 23, 48, thus indicating a SN2-like concerted nucleophilic attack/ring-opening mechanism (vide infra). Interestingly, 1,1-diaryl substituted cyclopropane was also competent substrate, which delivered the desired product 24 in moderate yield. Finally, an intramolecular ring-opening cyclization took place readily under the standard conditions to afford tetrahydrofuran derivative 26 in 78% yield.

Subsequently, the scope of nucleophile was explored. As for the oxygen-based nucleophile, a panel of structurally diversified alcohols containing different functional groups, differing in steric environment was tested first (Fig. 3). To our delight, primary alcohols such as methanol (49), (hetero)benzylic alcohol (54–56, 62–64), secondary alcohol such as isopropanol (50), 2-adamantanol (72) was applicable, delivering the desired products in moderate to good yields. Unfortunately, tertiary alcohol is not amenable under the current conditions, perhaps due to its low nucleophilicity and steric hindrance. Of note, water was proved to be the competent nucleophile which directly offered tertiary alcohol product 57–59 in 61–77% yield. Furthermore, alcohols with various functional groups such as silyl ether (51, 52), Boc-protected amino group (53), terminal (61) or internal alkene (60) also readily engaged in this reaction, furnishing the desired products in moderate to good yields. To further showcase the synthetic applicability of this protocol, late-stage elaboration of a repertoire of natural product or pharmaceutical relevant alcohols were interrogated, which delivered respective alkylation products in synthetically useful yields (65–67, 69–71, 73). Finally, when 1,5-pentanediol was employed, a twofold functionalization was observed, giving rise to the product 68 in 61% yield.

Reaction conditions: arylcyclopropane (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), alcohol (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv.), photocatalyst (2 mol%), (PhS)2 (0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), 2,6-ditBu-Py (0.05 mmol, 0.25 equiv.) and DCE (1.0 mL, 0.2 M) at 25 oC for 48 h under irradiation of a 15 W blue LED lamp. 57–59, H2O (2 mmol, 10 equiv.) and dioxane (1.0 mL, 0.2 M) was used as nucleophile and solvent, respectively.

Aside from alcohol, carboxylic acid also turned out to be competent O-type nucleophile, which provides an effective route for the ready access of sterically congested alkyl ester (Fig. 4). It is worthy of note that Baran’s technic for decarboxylative ether synthesis could not be readily extrapolated for alkyl ester construction by leveraging cross-coupling of two different carboxylic acid molecules through selective mono-decarboxylation. During the course of substrate exploration, we found a wide spectrum of functionalities were well tolerated and carboxylic acids with diverse structure motifs engaged in this reaction. Aliphatic (74–76) and aromatic carboxylic acids (77) reacted with arylcyclopropanes with ease to produce the desired products in good yields. Despite the radical nature of reaction, the employment of unsaturated carboxylic acids (78–80) were also rewarding, without any interference on the reaction progress. Intriguingly, when using allylsulfone-derived carboxylic acid, the reaction proceeded smoothly to afford the desired product 80 in 74% yield and no radical-type desulfonylative annulation product was detected probably because of the kinetically unfavored 7-endo-trig radical cyclization as compared with HAT quenching process in this specific example. Furthermore, pharmaceutical (81–84, 86) and natural product (85) relevant carboxylic acids were also well accommodated in this reaction, showcasing the potential applicability of the present method. In accordance with intramolecular etherification, a carboxylic acid tethered cyclopropane delivered lactone 87 in excellent yield via an intramolecular ring-opening substitution process.

The generality of nitrogen-based heterocycle and other nucleophile was also briefly examined (Fig. 5). Pyrazole derivatives with 4-substituents such as Cl, Br, Me and 3-TBS derivative, as well as 1H-indazole, were all found to take part in this reaction smoothly and afforded the desired products in moderate to good yields (88–92). In addition, triazole derivatives were also applicable, though they are inclined to trigger the formation of regioisomeric products (93, 94 and 95, 96). Moreover, trimethylsilyl azide and trimethylsilyl isothiocyanate as proton-free nucleophilic reagents also turned to be competent under current conditions, affording respective products 97 and 98 in high yields with stoichiometric amount of tertiary alcohol as the hydrogen source (see Supplementary Methods for more details). The synthetically useful azide and thiocyano group provide versatile handles for divergent follow-up transformations.

88–96: arylcyclopropane (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), heterocycle (1.5 equiv.), photocatalyst (2 mol%), (PhS)2 (0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), 2,6-ditBu-Py (0.05 mmol, 0.25 equiv.) and DCE (1.0 mL, 0.2 M) at 25 °C for 48 h under irradiation of a 15 W blue LED lamp. 97–98: arylcyclopropane (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), TMSN3/TMSNCS (2.0 equiv.), 2-methyl-2-butanol (0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), photocatalyst (2 mol%), (PhS)2 (0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), 2,6-ditBu-Py (0.05 mmol, 0.25 equiv.) and DCE (1.0 mL, 0.2 M) at 25 °C for 48 h under irradiation of a 15 W blue LED lamp. 99– 110: arylcyclopropane (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.), 2,6-lutidine hydrochloride/triethylamine trihydrofluoride (2.0 equiv.), photocatalyst (2 mol%), (PhS)2 (0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), 2,6-ditBu-Py (0.05 mmol, 0.25 equiv.) and DCE (1.0 mL, 0.2 M) at 25 °C for 48 h under irradiation of a 15 W blue LED lamp. TMSN3, azidotrimethylsilane. TMSNCS, trimethylsilylisothiocyanate.

Upon further exploration, we found that the applicable nucleophile was not restricted to oxygen or nitrogen-based entities, chlorination and fluorination could occur readily by using 2,6-lutidine hydrochloride and triethylamine trihydrofluoride as nucleophiles, respectively. For arylcyclopropane without alkyl substituent and symmetric 1,2-aryl cyclopropane, the 1,3-hydrochlorination reaction delivered the desired products in excellent yields (100, 101). Interestingly, when 1,2-arylalkyl cyclopropane was employed, two regioisomeric chlorination products were observed in excellent yields but low regioselectivity (104:105 = 3.3:1, 96% and 106:107 = 2.3:1, 95%), which is in stark contrast to the aforementioned C–O and C–N bond formation reactions. In comparison, when using gem-dimethyl substituted aryl cyclopropane the reaction took place in high efficiency and regioselectivity (108, 99), whereas in the former case the obtained product was not stable, which underwent a spontaneous elimination reaction to afford isomeric mixture of alkene products (109:110 = 2:1). In contrast, the corresponding fluorinated products were quite stable and 102, 103 were obtained in good yields.

Mechanistic investigations

In order to gain a deep insight into the mechanism, a set of control experiments were then executed. Firstly, a light “on–off” experiment demonstrated the necessity of continuous irradiation for the progress of this transformation. Secondly, addition of stoichiometric amount of TEMPO as radical inhibitor into the reaction of 1 and ethanol led to complete inhibition of product formation (Fig. 6a). Moreover, a radical clock experiment with 111 was conducted, which uneventfully delivered a cascade ring-opening product 112 in 88% yield, thus substantiating the involvement of benzylic radical intermediate in this reaction (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the quantum yield of reaction between 1 and ethanol was determined to be 0.182, indicating that radical chain process may not be the major pathway (see Supplementary Discussion for more details).

To further clarify the source of hydrogen at benzylic site of the product, control experiments were performed under standard conditions while using CDCl3 as the reaction solvent, D4-methanol and methanol as respective nucleophiles (Fig. 6c). Though both reactions gave corresponding products in high yields (113 and 114), only reaction with D4-methanol led to the incorporation of considerable amount of deuterium at benzylic position (113). This result clearly demonstrated that the proton of the nucleophile, other than the solvent, was transferred to the benzylic site of the product.

In our previous work42, the cyclopropane ring-opening step has been proved to take place through a concerted nucleophilic attack/ring-opening SN2-like manner. To determine whether concerted nucleophilic SN2 ring-opening functionalization is also involved in the present reaction, control experiment with enantiomerically enriched trans-1,2-diphenyl cyclopropane42 114 (90% ee) was examined with ethanol under the standard reaction conditions, which resulted in the generation of product 18 with 85% ee, thus unequivocally substantiate a concerted SN2-like process with complete stereoinversion (Fig. 7, eq. a). The somewhat erosion of stereochemistry was rationalized as resulting from minor contribution of substrate racemization. Such stereochemistry scrambling could occur through either triplet energy transfer or SET-induced reversible ring-cleavage of cyclopropane substrate (see Supplementary Discussion for more details). To further probe the generality of the stereoinvertive ring-opening substitution, more enantioenriched structurally differing substrates were tested. A 1,2-diaryl cyclopropane 115 with an electron-deficient benzothiazole also underwent the reaction smoothly to afford enantiopurity conserved product 116 in high yield and excellent regioselectivity (Fig. 7, eq. b). Furthermore, under standard conditions, with 2,6-lutidine hydrochloride as nucleophile, an enantioenriched 1,2-arylalkyl-substituted cyclopropane 117 with a naked hydroxyl group underwent chemoselective chloride attack, without intramolecular epoxidation or intermolecular ether formation being observed. However, as in the case of 104 and 106, two regioisomeric chlorination products were observed, with enantiopurity fully conserved product 118 being the minor isomer (Fig. 7, eq. c). The unique reactivity of chloride was intriguing as previous mechanistic study and other cases in this work all showed a high regioselectivity for nucleophilic attack at the more substituted carbon atom50. We ascribed this unusual selectivity to the high nucleophilicity of naked chloride ion thus resulting in relatively small difference of energy barriers for site discrimination.

During the investigation, the apparently abnormal regioselectivities in some cases have attracted our attention (19, 20, 43, 44, 45, 116). Aiming to provide an explanation for the regioselectivity of these 1,2-diaryl cyclopropanes, we have conducted DFT calculation to study the frontier molecular orbitals of cation radical of some representative substrates. The DFT calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 program. Geometries of the minimum energy structures were optimized at the B3-LYP level of theory with the 6-31G(d, p) basis. As shown in Fig. 8, the highest contribution of LUMO orbital is located at the α position of the more electron-rich aryl ring (C3 site of 120-Int and C2 site of 115-Int), which is also the reaction site of nucleophilic substitution. Furthermore, the frontier molecular orbital of radical cation of model substrate 1-Int was calculated and the result indicates the highest LUMO orbital coefficient at the dialkyl substituted carbon. Taken together, we believe that regioselectivity of this three-electron SN2 reaction was subjected to an orbital control scenario whereby the site with higher LUMO orbital coefficient is more prone to be attacked by external nucleophiles (see Supplementary Discussion for more details of the DFT calculation).

Schematic representation of 120-int, 115-int, and 1-int (top) along with the representation of their frontier molecular orbitals (bottom). See Supplementary Information for more details of the DFT calculations.

Based on the above experimental results, a plausible mechanism was proposed (Fig. 9). Initially, the excited-state of acridinium catalyst was reached by visible light excitation (450 nm). Then reductive quenching of the excited photocatalyst by aryl cyclopropane produced arylcyclopropyl cation radical58,59 intermediate I, which characteristically resembles the donor-acceptor cyclopropane37,38,39,40,41,42, and acridinium radical as one-electron-reduced catalyst. The subsequent nucleophilic attack of nucleophile selectively afforded ring-opened carbon centered radical intermediate II. The target product was finally produced via hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the thiol, accompanied by the generation of thiol radical. The active HAT agent was regenerated via reduction of the thiol radical by acridinium radical associated with subsequent proton transfer68, meanwhile closing the photocatalysis cycle.

Discussion

In summary, by taking the advantage of synergistic effect of photocatalyzed SET-oxidation and strain-release, we have developed a protocol for sterically congested C(sp3)–heteroatom bond construction via ring-opening cleavage of C–C bond of electronically unbiased arylcyclopropanes. The reaction features a wide applicability to different kinds of nucleophiles, including alcohol, carboxylic acid, sulfonamide, nitrogen-containing heteroaromatic, chloride and even water, excellent regioselectivity, mild reaction conditions, redox-neutral process. Wide substrate scopes with respect to both cyclopropane and nucleophile are delineated and late-stage functionalization of an array of natural product and pharmaceutical molecule derivates are also presented. Mechanistic studies prove a SN2-like ring-opening mechanism, which provides opportunity for the construction of synthetically challenging chiral quaternary stereocenters with enantiometically enriched substrates. More diverse patterns of ring-opening functionalization of arylcyclopropane are under way in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the C–O bond formation with alcohol as nucleophile

In a typical experiment, to a mixture of (PhS)2 (9.0 mg, 0.04 mmol), PC-VIII (2.3 mg, 0.004 mmol) and propan-2-ol (24 mg, 0.4 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (1.0 mL) was added 2,6-di-tBu-Py (9.6 mg, 0.05 mmol) and arylcyclopropane 1 (0.2 mmol) under nitrogen atmosphere. After 48 h irradiation with a 15 W blue LED lamp (l = 459 nm) at room temperature, the mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, and the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product 50 (42.5 mg, 90%). The reaction with other kind of nucleophile were carried out similarly and the procedures are presented in Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

Detailed experimental procedures and characterization of new compounds are available in Supplementary Information. For condition optimization and experimental procedures, see Supplementary Methods. For mechanistic studies, spectroscopic data, HPLC and NMR spectra of compounds, see Supplementary Discussion. Further relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lovering, F., Bikker, J. & Humblet, C. Escape from flatland: Increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752–6756 (2009).

Zhang, X. & Tan, C.-H. Stereospecific and stereoconvergent nucleophilic substitution reactions at tertiary carbon centers. Chem 7, 1451–1486 (2021).

Williamson, W. Ueber die theorie der aetherbildung. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 77, 37–49 (1851).

Diamanti, A. et al. Mechanism, kinetics and selectivity of a Williamson ether synthesis: Elucidation under different reaction conditions. React. Chem. Eng. 6, 1195–1211 (2021).

Swamy, K. C. K., Kumar, N. N. B., Balaraman, E. & Kumar, K. V. P. P. Mitsunobu and related reactions: Advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 109, 2551–2651 (2009).

Fletcher, S. The Mitsunobu reaction in the 21st century. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 739–752 (2015).

Smith, M. B. & March, J. March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry 6th edn 1037–1041 (Wiley, 2007).

Dryzhakov, M., Hellal, M., Wolf, E., Falk, F. C. & Moran, J. Nitro-assisted Brønsted acid catalysis: Application to a challenging catalytic azidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9555–9558 (2015).

Pronin, S. V., Reiher, C. A. & Shenvi, R. A. Stereoinversion of tertiary alcohols to tertiary-alkyl isonitriles and amines. Nature 501, 195–199 (2013).

Wendlandt, A. E., Vangal, P. & Jacobsen, E. N. Quaternary stereocentres via an enantioconvergent catalytic SN1 reaction. Nature 556, 447–451 (2018).

Xiang, J. et al. Hindered dialkyl ether synthesis with electrogenerated carbocations. Nature 573, 398–402 (2019).

Shibutani, S. et al. Organophotoredox-catalyzed decarboxylative C(sp3)–O bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 1211–1216 (2020).

Mao, R., Balon, J. & Hu, X. Decarboxylative C(sp3)–O cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13624–13628 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. An enantioconvergent halogenophilic nucleophilic substitution (SN2X) reaction. Science 363, 400–404 (2019).

Hirata, G. et al. Chemistry of tertiary carbon center in the formation of congested C–O ether bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 4329–4334 (2021).

Shibatomi, K., Soga, Y., Narayama, A., Fujisawa, I. & Iwasa, S. Highly enantioselective chlorination of β-keto esters and subsequent SN2 displacement of tertiary chlorides: a flexible method for the construction of quaternary stereogenic centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9836–9839 (2012).

Lamhauge, J. N., Corti, V., Liu, Y. & Jøgensen, K. A. Enantioselective α-etherification of branched aldehydes via an oxidative umpolung strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18728–18733 (2021).

Rezayee, N. M. et al. An asymmetric SN2 dynamic kinetic resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7509–7520 (2021).

Kaga, A. & Chiba, S. Engaging radicals in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling with alkyl electrophiles: Recent advances. ACS Catal. 7, 4697–4706 (2017).

Fu, G. C. Transition-metal catalysis of nucleophilic substitution reactions: a radical alternative to SN1 and SN2 processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 692–700 (2017).

Kainz, Q. M. et al. Asymmetric copper-catalyzed C–N cross-couplings induced by visible light. Science 351, 681–684 (2016).

Matier, C. D., Schwaben, J., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Copper-catalyzed alkylation of aliphatic amines induced by visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17707–17710 (2017).

Chen, C., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Photoinduced copper-catalysed asymmetric amidation via ligand cooperativity. Nature 596, 250–256 (2021).

Peacock, D. M., Roos, C. B. & Hartwig, J. F. Palladium-catalyzed cross coupling of secondary and tertiary alkyl bromides with a nitrogen nucleophile. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 647–652 (2016).

Liang, Y., Zhang, X. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Decarboxylative sp3 C–N coupling via dual copper and photoredox catalysis. Nature 559, 83–88 (2018).

Marcyk, P. T. et al. Stereoinversion of unactivated alcohols by tethered sulfonamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1727–1731 (2019).

Watile, R. A. et al. Intramolecular substitutions of secondary and tertiary alcohols with chirality transfer by an iron(III) catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 3826 (2019).

Gianatassio, R. et al. Strain-release amination. Science 351, 241–246 (2016).

Lopchuk, J. M. et al. Strain-release heteroatom functionalization: Development, scope, and stereospecificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3209–3226 (2017).

Tyler, J. L., Noble, A. & Aggarwal, V. K. Strain-release driven spirocyclization of azabicyclo[1.1.0]butyl ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11824–11829 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Copper-mediated synthesis of drug-like bicyclopentanes. Nature 580, 220–226 (2020).

Sabir, S., Kumar, G., Verma, V. P. & Jat, J. L. Aziridine ring opening: An overview of sustainable methods. ChemistrySelect 3, 3702–3711 (2018).

Zhan, X. & Du, X. Regio- and enantioselective epoxy ring opening of 2,3-epoxy-3-phenyl alcohols/carboxylic acids and their derivatives. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 56, 679–692 (2020).

Reissig, H.-U. & Zimmer, R. Donor−acceptor-substituted cyclopropane derivatives and their application in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 103, 1151–1196 (2003).

Schneider, T. F., Kaschel, J. & Werz, D. B. A new golden age for donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5504–5523 (2014).

Wallbaum, J., Garve, L. K. B., Jones, P. G. & Werz, D. B. Ring-opening 1,3-halochalcogenation of cyclopropane dicarboxylates. Org. Lett. 19, 98–101 (2017).

Das, S., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Lewis acid catalyzed stereoselective dearomative coupling of indolylboron ate complexes with donor–acceptor cyclopropanes and alkyl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4053–4057 (2018).

Lanke, V. & Marek, I. Nucleophilic substitution at quaternary carbon stereocenters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5543–5548 (2020).

Rao, V. R. & Hixson, S. S. Arylcyclopropane photochemistry. Electron-transfer-mediated photochemical addition of methanol to arylcyclopropanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 6458–6459 (1979).

Dinnocenzo, J. P., Simpson, T. R., Zuilhof, H., Todd, W. P. & Heinrich, T. Three-electron SN2 reactions of arylcyclopropane cation radicals. 1. Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 987–993 (1997).

Dinnocenzo, J. P., Zuilhof, H., Lieberman, D. R., Simpson, T. R. & McKechney, M. W. Three-electron SN2 reactions of arylcyclopropane cation radicals. 2. Steric and electronic effects of substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 994–1004 (1997).

Ge, L. et al. Photoredox-catalyzed oxo-amination of aryl cyclopropanes. Nat. Commun. 10, 4367 (2019).

Zuo, Z., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Cooperative NHC/photoredox catalyzed ring-opening of aryl cyclopropanes to 1-aroyloxylated-3-acylated alkanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25252–25257 (2021).

Zuo, Z. & Studer, A. 1,3-Oxyalkynylation of aryl cyclopropanes with ethylnylbenziodoxolones using photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 24, 949–954 (2022).

Kolb, S. et al. Electrocatalytic activation of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes and cyclobutanes: An alternative C(sp3)–C(sp3) cleavage mode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15928–15934 (2021).

Kolb, S., Ahlburg, N. L. & Werz, D. B. Friedel–Crafts-type reactions with electrochemically generated electrophiles from donor–acceptor cyclopropanes and -butanes. Org. Lett. 23, 5549–5553 (2021).

Tang, H.-J., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y.-F. & Feng, C. Visible-light-assisted gold-catalyzed fluoroarylation of allenoates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5242–5247 (2020).

Liu, H., Ge, L., Wang, D.-X., Chen, N. & Feng, C. Photoredox-coupled F-nucleophilic addition: Allylation of gem-difluoroalkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 3918–3922 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Intermolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10695–10699 (2018).

Tang, H.-J., Zhang, B., Xue, F. & Feng, C. Visible-light-induced Meerwein fluoroarylation of styrenes. Org. Lett. 23, 4040–4044 (2021).

Liu, H., Li, Y., Wang, D.-X., Sun, M.-M. & Feng, C. Visible-light-promoted regioselective 1,3-fluoroallylation of gem-difluorocyclopropanes. Org. Lett. 22, 8681–8686 (2020).

Wang, L., Lu, C., Yue, Y. & Feng, C. Visible-light-promoted oxo-sulfonylation of ynamides with sulfonic acids. Org. Lett. 21, 3514–3517 (2019).

Zhu, C. et al. Selective C–F bond carboxylation of gem-difluoroalkenes with CO2 by photoredox/palladium dual catalysis. Chem. Sci. 10, 6721–6726 (2019).

Romero, N. A. & Nicewicz, D. A. Mechanistic insight into the photoredox catalysis of anti-Markovnikov alkene hydrofunctionalization reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17024–17035 (2014).

Romero, N. A., Margrey, K. A., Tay, N. E. & Nicewicz, D. A. Site-selective arene C–H amination via photoredox catalysis. Science 349, 1326–1330 (2015).

Niu, L. et al. Visible-light-induced external oxidant-free oxidative phosphonylation of C(sp2)–H bonds. ACS Catal. 7, 7412–7416 (2017).

Bloom, S., McCann, M. & Lectka, T. Photocatalyzed benzylic fluorination: Shedding “light” on the involvement of electron transfer. Org. Lett. 16, 6338–6341 (2014).

Pandey, G., Pal, S. & Laha, R. Direct benzylic C–H activation for C–O bond formation by photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5146–5149 (2013).

Zheng, Y.-W. et al. Photocatalytic hydrogen-evolution cross-couplings: Benzene C–H amination and hydroxylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10080–10083 (2016).

Blum, T. R., Zhu, Y., Nordeen, S. A. & Yoon, T. P. Photocatalytic synthesis of dihydrobenzofurans by oxidative [3+2] cycloaddition of phenols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 11056–11059 (2014).

Zhou, R., Liu, H., Tao, H., Yu, X. & Wu, J. Metal-free direct alkylation of unfunctionalized allylic/benzylic sp3 C–H bonds via photoredox induced radical cation deprotonation. Chem. Sci. 8, 4654–4659 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. One-pot photomediated Giese reaction/Friedel–Crafts hydroxyalkylation/oxidative aromatization to access naphthalene derivatives from toluenes and enones. ACS Catal. 8, 6224–6229 (2018).

Ohkubo, K., Mizushima, K., Iwataa, R. & Fukuzumi, S. Selective photocatalytic aerobic bromination with hydrogen bromide via an electron-transfer state of 9-mesityl-10-methylacridinium ion. Chem. Sci. 2, 715–722 (2011).

Baciocchi, E., Bietti, M. & Lanzaunga, O. Mechanistic aspects of β-bond-cleavage reactions of aromatic radical cations. Acc. Chem. Res. 33, 243–251 (2000).

Nguyen, T. M. & Nicewicz, D. A. Anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of alkenes catalyzed by an organic photoredox system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9588–9591 (2013).

Nguyen, T. M., Manohar, N. & Nicewicz, D. A. anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of alkenes catalyzed by a two-component organic photoredox system: Direct access to phenethylamine derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6198–6201 (2014).

Joshi-Pangu, A. et al. Acridinium-based photocatalysts: A sustainable option in photoredox catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 81, 7244–7249 (2016).

Wilger, D. J., Gesmundo, N. J. & Nicewicz, D. A. Catalytic hydrotriflfluoromethylation of styrenes and unactivated aliphatic alkenes via an organic photoredox system. Chem. Sci. 4, 3160–3165 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21871138, 22271151), the Distinguished Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Province, and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20220327).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F. directed the investigations. C.F. and C.Z. prepared the manuscript. L.G., C.Z, C.P., D.W., D.L., Z.L., and P.S. performed the synthetic experiments and analyzed the experimental data. L.T. performed the DFT calculations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Daniel Werz, Adam Noble and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, L., Zhang, C., Pan, C. et al. Photoredox-catalyzed C–C bond cleavage of cyclopropanes for the formation of C(sp3)–heteroatom bonds. Nat Commun 13, 5938 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33602-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33602-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.