Abstract

Van der Waals clusters are weakly bound atomic/molecular systems and are an important medium for understanding micro-environmental chemical phenomena in bio-systems. The presence of neighboring atoms may open channels otherwise forbidden in isolated atoms/molecules. In hydrogen-bond clusters, proton transfer plays a crucial role, which involves mass and charge migration over large distances within the cluster and results in its fragmentation. Here we report an exotic transfer channel involving a heavy N+ ion observed in a doubly charged cluster produced by 1 MeV Ne8+ ions: (N2Ar)2+→N++NAr+. The neighboring Ar atom decreases the \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) barrier height and width, resulting in significant shorter lifetimes of the metastable molecular ion state \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\)(\({{\mathrm{X}}^{1}}{\Sigma _{{\mathrm{g}}}^{+}}\)). Consequently, the breakup of the covalent N+−N+ bond, the tunneling out of the N+ ion from the \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) potential well, as well as the formation of an N−Ar+ bound system take place almost simultaneously, resulting in a Coulomb explosion of N+ and NAr+ ion pairs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Van der Waals (vdW) interactions are ubiquitous in nature and important for many physical and chemical phenomena. A good understanding of intermolecular interaction is essential since weakly bond systems widely exist in biology and play a key role as a reactive intermediate in many processes. Weak bonds may be easily broken but they are very important because they enable to determine and stabilize the shape of biological molecules, such as stabilizing the secondary structure (e.g. alpha-helix and beta-pleated sheet) of proteins1. Dimers are good prototypes to investigate this weakly bound interaction. Indeed, atomic/molecular dimers have a typical weak binding energy in the order of meV and have a large distance between its two components usually above 7 a.u., which exceeds the covalent bond in molecules (~2 a.u.). Although weakly bound rare gas dimers have been studied extensively during the last two decades2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, studies of dimers consisting of one or two diatomic molecules remain rare, some examples can be found in refs. 16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Therefore, it is essential to understand the structure and fragmentation/dissociation dynamics of charged molecular dimers at the level of molecular motion2.

A prominent example is the interatomic Coulumbic decay (ICD) theoretically predicted in 1997 (ref. 3), where electronic excitation energy is efficiently transferred over a large internuclear distance within a rare gas dimer to allow for fast nonradiative relaxation. In 2003, ICD was first observed experimentally in Ne2 rare gas cluster following inner-valence electron ionization5. Later, numerous experiments, where photons, electrons, and heavy ions were used as projectiles, have been performed to confirm the ICD and new dissociation mechanisms have been found in different rare gas dimers or larger clusters6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28, such as radiative charge transfer8,15 or electron-transfer-mediated decay10,27. For this kind of processes, the energy and charge transfer are mediated by virtual photon/Coulomb interaction, or electron transfer. In addition to the mechanisms mentioned above, an intermolecular proton transfer was reported in the molecular dimers, such as acetylene dimer29, water cluster23,30, and ammonia clusters31. In this process, a proton is transferred from a parent molecule to its partner molecule in a dimer which is bound together by hydrogen bond, and then, leading to a dissociation breakup. Since the discovery of the double helix form of DNA and the hypothesis of DNA mutation induced by proton transfer32 more than 50 years ago, it has been recognized that proton transfer is crucial in many chemical and biological processes33. For example, a proton transfer reaction may produce a rare tautomer, which is regarded as the source of spontaneous mutations, and might lead to some important biochemistry processes related to other relevant diseases such as cellular aging and cancer32,34. On the other hand, there are excited-state proton transfer and multiple proton transfer processes which also play vital roles in biological systems. Nowadays, at the molecular level the simulations employing quantum chemistry could help us to have a thorough and detailed understanding of the mechanism of chemical and biological processes relevant to DNA, heredity, mutation, cancer, and green fluorescence protein, etc.35.

In this article, we report a dissociation breakup mechanism of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\) cluster induced by heavy N+ ion transfer: \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}} \to {\mathrm{N}}^ + + {\mathrm{NAr}}^ +\). Here, the strong covalent bond N–N breaks up and a new N–Ar bond is formed, due to N+ transfer from \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) center to Ar in doubly charged \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\). To the best of our knowledge, such a heavy ion transfer process in vdW cluster has never been reported before and the consequent formation of NAr+ is a novel scenario. It is intriguing to build bridges between the heavy ion transfer processes and biological processes at molecular level in the micro-environment of biological system as well as, for example, in the understanding of micro-mechanism of cancer therapy by heavy ion irradiations.

Results

Identification of heavy ion transfer channel

In the present work, doubly charged cluster (N2Ar)2+ ions are produced by using 1 MeV Ne8+ ions impact on neutral vdW cluster N2Ar target, and the fragment ions are detected in coincidence with the scattered ions. The information of time-of-flight (TOF) and positions of each charged fragment arriving at the detector is used to reconstruct their three-dimensional initial momentum vectors (see Methods). Figure 1 shows the two-dimensional correlation map between the TOFs of the first and the second fragment ions produced in Ne8+–N2Ar collisions with one or two electrons stabilized on the projectile. At the top of horizontal axis the ion species and charge states corresponding to the TOF1 are labeled. Similarly, the ion species and charge states corresponding to the TOF2 (vertical axis) are also indicated. Usually, the different reaction channels can be identified according to the charge conservation before and after the collision. As a general rule for TOF correlation map, the slash lines are characteristics of two-body dissociation processes, while the extended area around the slash lines originates from the three-body or multi-body fragmentation36. Taken as an example, the fragment products as labeled in Fig. 1 can be identified mainly from the following dissociation channels of the doubly charged dimers:

The coincidence map shows the time-of-flights between the first and the second fragment ions arriving at the detector. The product ion species are labeled in the plot for horizontal and vertical axes according to their TOFs, respectively. The corresponding reactions labeled with a number are explained in the text.

However, there is one two-body dissociation channel labeled (4) in Fig. 1 which cannot be simply identified as a direct fragmentation of the vdW dimer N2Ar according to the above mentioned rules. From calibration we find that one fragment has a charge to mass ratio of 1/14, while the correlated fragment has a charge to mass ratio of 1/54. It is surprising, because none of the dimer components and probable residual gaseous atoms have such a combination of charge to mass ratios. The coincidence measurement between (1/14)+ and (1/54)+, charge to mass ratio fragments, suggests that this channel corresponds to the following reaction:

In this reaction channel, a significant discovery is that a heavy N+ ion (mass = 14) is transferred from one molecule center (\({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\)) to the other (Ar) in the dimer. One has to note that this exotic dissociation channel means that after the N2Ar dimer loses two electrons, the strong N–N covalent bond breaks up and, due to the presence of the Ar atom, a new N–Ar bond is formed. We refer to this channel as N+ ion transfer channel. From the potential energy curves (PECs) of NAr+ (ref. 37), the stable molecular ion NAr+ can only be formed from N+ ion and neutral Ar atom. This suggests that the channel (4) can only originate from the \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\) parent dimer ion.

Kinetic energy release of N+ ion transfer channel

The kinetic energy release (KER) distribution of N+ ion transfer channel shows a single peak at 4.9 eV as illustrated in Fig. 2. In the reaction (4), N+ ion transits from an initially bound \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) state to a final NAr+ bound state. On the other hand, the KER results from three contributions: the first one is the polarization energy of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + } - {\mathrm{Ar}}\) bond, which is very weak and can be ignored; the second one is the dissociation energy of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\), which is determined from the initial electronic metastable state of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\), and the last one is the binding energy of NAr+. According to the PEC of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) molecular ion 38, the \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) molecular ion of N2Ar dimer could be populated in the low-lying electronic states, namely, \({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}}\), a3Πu, \({\mathrm{D}}^3\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{u}}^{+}}\), A1Πu, and \({\mathrm{A}}^3\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{-}}\), etc. However, from the measured KER = 4.9 eV, we infer that the N+ ion transfer channel originates essentially from the relaxation of low vibrational levels of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) and \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{a}}^3\,{\Pi}_{\mathrm{u}}){\mathrm{Ar}}\) states, because their dissociation energy is less than 4.9 eV. Here, the neutral Ar in the dimer plays a crucial role in the dissociation process of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) \(({{\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ,\,{\mathrm{a}}^3{\Pi}_{\mathrm{u}}})\) dication.

Discussion

To understand the reaction mechanism of N+ ion transfer channel, let us first consider the PECs of the doubly charged cluster (N2Ar)2+. We mainly focus on the relaxation of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\), which should be more important than the relaxation of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{a}}^3\,{\Pi}_{\mathrm{u}}){\mathrm{Ar}}\) due to the fact that the \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} )\) state is predominantly located at the dissociation energy region allowed by Frank–Condon transition. The PECs for \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) along the N2–Ar dimer axis are calculated as shown in Fig. 3, see calculation of PECs in Methods. A comparison of the PECs for the linear-shaped and T-shaped \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) dimer is displayed in Fig. 3. It is clearly shown that the energy minimum for linear-shaped \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\) locates at \({\mathrm{R}}_{{\mathrm{N}}_2 - {\mathrm{Ar}}} = 7.2\,{\mathrm{a}}.{\mathrm{u}}.\) and is about 0.2 eV lower than the one for T-shaped, (here, RX–Y defines the distance between the Y atom and the center of mass of the X molecule in the whole context). It is well known that neutral N2Ar cluster has a T-shaped structure16,17,18. When the Ne8+ projectile captures two electrons from N2-site of neutral N2Ar cluster, \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\) ion should undergo firstly an isomerization process going from an initial T-shape to a linear-shape, and then vibrate in the vicinity of the minimum before dissociation.

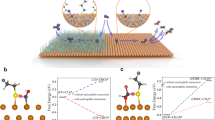

With the help of theoretical PECs, we present an intuitive physical picture of the heavy N+ ion transfer reaction. Different from the PEC of the monomer \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) (black solid curve in Fig. 4), the PEC of linear-shaped \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }{\mathrm{Ar}}\) along the N+–N+ bond is exhibited by a red dashed curve in Fig. 4, where the influence of neutral Ar atom on the potential energy of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) is considered. It is clearly shown that a new potential well, due to the presence of Ar atom, can be found as the RN–N (upper horizontal axis in Fig. 4) increases, and its minimum locates at RN–N = 7.8 a.u., corresponding to the distance RN–Ar = 7.2–7.8/2 = 3.3 a.u. This clearly suggests that a stable NAr+ molecular ion could be formed.

The PECs of \({{\mathrm{N}}_{2}^{2+}}({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) with/without the presence of neutral Ar along RN–N (upper horizontal axis) and N+–NAr+ along RN–NAr (bottom horizontal axis). The black solid curve for \({{\mathrm{N}}_{2}^{2 + }}({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} )\) without the neutral Ar, the red dashed curve for \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) at fixed distance \({\mathrm{R}}_{{\mathrm{N}}_2 - {\mathrm{Ar}}} = 7.2\,{\mathrm{a}}.{\mathrm{u}}\), and the blue solid curve indicates the PEC of N+–NAr+ with \({\mathrm{R}}_{{\mathrm{N}} - {\mathrm{Ar}}} = 3.3\,{\mathrm{a}}.{\mathrm{u}}\). The gray areas indicate the possibly populated initial and final vibrational states of \({\rm{N}}_{2}^{2+}{\mathrm{{Ar}}}\) and NAr+ ions, respectively, which contribute to the heavy ion transfer channel. The final NAr+ potential well is plotted on the left. The pink dashed arrow indicates the N+ ion tunneling. The green wave line indicates the intermediate state of ion NAr+. The origin arrow indicates the fragmentation of N+ and NAr+ ion pair via Coulomb explosion. The origin of the potential energy curves is taken such that the potential energy of N+, N+, and neutral Ar at large separations is zero. The light blue ball represents nitrogen atom while the black ball represents argon atom.

However, to form the NAr+ ion, the N+ ion, initially bound to \({\rm{N}}_{2}^{2+}\) molecule, has to overcome the barrier Ec (i.e. the breakup of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) covalent bond) and to be trapped in the NAr+ well, which is of course extremely difficult. The only possible pathway is tunneling, namely, the N+ ion from the left potential well of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\,({\mathrm{in}}\,{\mathrm{vibration}}\,{\mathrm{states}}\,v = {\mathrm{a}})\) tunnels into the right potential well of N++NAr+ (the pink dashed arrow in Fig. 4), and the NAr+ is formed in high vibrational levels (v = b) (see the green wave line). Then, the Coulomb explosion between N+ and NAr+ ion pair takes place along the blue solid curve as shown in Fig. 4. Due to the strong couplings between Coulomb repulsion and vibration of NAr+ at close distances, the NAr+ at high vibration levels (v = b) can be converted to lower vibration states (v = c). The correlation between the KER of N+ ion transfer channel and the initial states can be estimated. The initial energy of the doubly charged cluster \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) consists of a sum of minimum potential energy Ei and vibration energy Ea (v = a). Similarly, the final potential energy of the system is given by adding the minimum potential energy Ef and the vibration energy Ec (v = c). On the other hand, as the energy of the system before and after the heavy ion transfer is conserved, as a result, the KER could be obtained as follows: KER = (Ei+Ea) − (Ef + Ec). Namely, 4.9 = (4.0 + Ea) − (−2.05 + Ec), that is, Ec − Ea = 1.15 eV. Because the final maximum vibration energy is 2.05 eV, while the initial minimum vibration energy is 0 eV, the only possible vibration energies for initial and final states are restricted in the range of 0.0–0.9 and 1.15–2.05 eV, respectively, as shown by the gray areas in Fig. 4.

One has to note that, the monomer \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) is a metastable ion which has very long lifetimes. The lifetime of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} )\) state for its vibrational level v = 8 is as long as 312.5 days (2.7 × 106 s) 39, and is even longer for v < 8 states. However, for the dimer \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({{\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} }){\mathrm{Ar}}\), the nearby Ar atom modifies the monomer’s potential and leads to significant changes of the lifetimes. We calculated the tunneling lifetimes of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} )\) in the presence of Ar atom with \({\mathrm{R}}_{{\mathrm{N}}_2 - {\mathrm{Ar}}} = 7.2\,{\mathrm{a}}.{\mathrm{u}}.\) using the complex absorption potential40, see lifetime estimation in Methods. The calculated tunneling lifetimes of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} )\,\left( {v = 4,5,6} \right)\) are 1110, 245, and 69 ns (1 ns = 10−9 s), respectively, which means its lifetime can be reduced by more than 12 orders of magnitude in the doubly charged dimer \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\), from hundred days to nanoseconds. This strongly indicates that, because of the neighboring Ar atom, the originally quasi-stable monomer ions \({\rm{N}}_{2}^{2+}\) can dissociate rapidly by tunneling through the potential barrier, form the NAr+ ion and, hence, create the N+–NAr+ ion pair.

The heavy ion transfer scenario in a charged dimer may be general for molecular dimer ions such as AB2+X as long as two conditions are met: (i) the metastable covalent bond A–B is toward the neutral particle X, which is the case for most diatomic molecular ions and also for other polar covalent bonds, such as C–H bond; (ii) the neutral particle X and the neighboring ion A+/B+ can form a bound system XA+/XB+. This kind of ion transfer process may have potential importance in understanding the underlying mechanisms of biochemistry in tissues, and play an important role in the irradiation damage caused by ion or electron radiation, and furthermore, may directly affect the expression of DNA and protein in vivo.

In conclusion, we present a channel of heavy N+ transfer and NAr+ ion formation in the two-body dissociation of (N2Ar)2+ dimer ion, which results from the breakup of linear-shaped dimer ion \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ,\,{\mathrm{a}}^3\,{\Pi}_{\mathrm{u}}){\mathrm{Ar}}\). This transfer mechanism is explained by the tunneling of the heavy N+ ion and, hence, leads to the formation of NAr+ ion. The dissociation of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\)(\({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}}\)) states through the tunneling of N+ becomes possible due to the presence of Ar atom in the dimer. Consequently, the N+–N+ bond breaks up quickly, and the tunneling of N+ ion and the formation of N+–Ar bond take place almost simultaneously. This is viewed as bound–bound states transition of the heavy ion of N+, followed by Coulomb explosion between N+ and NAr+ ion pairs. Such a mechanism of heavy ion transfer may be general for any molecular dimer ions of type AB2+X, and may be of potential importance in various biochemical processes.

Methods

Experimental approaches

Our experiment was conducted at 320 kV platform for multidisciplinary research with highly charged ions in the Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou41. A standard Cold Target Recoil Ion Momentum Spectroscopy/Reaction Microscope was employed to determine the momentum of each fragments in coincidence41,42,43. The highly charged Ne8+ ions were produced by the permanent magnet electron cyclotron resonance ion source and were accelerated to an energy of 1 MeV. Then the Ne8+ ions were delivered to the reaction chamber, where it crossed a supersonic gas target. Various dimers were generated in the molecular jet, such as N2Ar, (N2)2, and Ar2, by expanding a mixture gas of N2 and Ar through a 30-μm nozzle at 20 bars stagnation pressure under room temperature. The gas pressure ratio in the mixture was N2:Ar ∼ 1:1. Charged fragments produced in the collisions were guided by 173 V/cm uniform electric field to a position-sensitive multi-hit detector with a position resolution of 0.1 mm. The information of positions and the TOF of each charged fragment arriving at the detector are obtained; consequently, their three-dimensional initial momentum vectors can be reconstructed by off-line analysis. Downstream, the projectile ions were collected by a Faraday-Cup and the scattered Ne7+ and Ne6+ ions were detected by a delay-line anode detector. The fragment momentum calibration is carried out in the same conditions by the two-body dissociation of monomer \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }\) ions, which has clearly separated and known peaks38.

Calculations of PECs

The PECs calculations for \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) along the N2–Ar dimer axis are performed using the multi-reference double-excited configuration interaction44 method with molecular orbitals optimized by complete active space self-consistent field method45,46,47. Here the active space consists of all valence orbitals and totally about 1000 reference configuration state functions are considered in configuration interaction calculations. The orbital wave functions are expanded on aug-cc-pVtZ basis set. The same method is used to calculate the PECs of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,\mathop {\Sigma}\nolimits_{\rm{g}}^{+})\) and NAr+. Then, the PEC of linear-shaped \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) along the N–N bond is calculated using the two-body potential model48, where only the two-body correlation interactions are considered based on the PECs of \({\rm{N}}_{2}^{2+}\) and NAr+, and the three-body correlation interaction is neglected. Such a model is reasonable for the PECs calculation of linear-shaped \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) since one of the N+ ions is far away from Ar (>8 a.u.) and the three-body correlation interaction is very weak.

Lifetime estimation

Based on the PECs obtained, the lifetimes of \({\mathrm{N}}_2^{2 + }({\mathrm{X}}^1\,{{\Sigma}_{\mathrm{g}}^{+}} ){\mathrm{Ar}}\) are calculated using the complex absorption potential (CAP) method49,50. In the CAP calculations, the nuclear Hamiltonian H (η) is extended by a small absorbing potential

and

in which η is a variation parameter and R0 = 10 a.u. is used in the present calculation. A set of η values are selected to solve the eigenvalue equation

and the eigenvalue of resonant state can be obtained with the condition of

Finally, the eigenvalue we obtain is as follows:

where E0 is the resonant energy, Γ is the resonant width or decay rate, and τ = 1/Γ is the lifetime.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The data supporting this study are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the theoretical plots within this paper is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Campbell, N. & Reece, J. Biology (Benjamin Cummings, 2005).

Linnartz, H., Verdes, D. & Maier, J. P. Rotationally resolved infrared spectrum of the charge transfer complex [Ar–N2]+. Science 297, 1166 (2002).

Cederbaum, L. S., Zobeley, J. & Tarantelli, F. Giant intermolecular decay and fragmentation of clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 4778 (1997).

Zobeley, J., Santra, R. & Cederbaum, L. S. Electronic decay in weakly bound heteroclusters: energy transfer versus electron transfer. J. Chem. Phys. 115, 5076 (2001).

Marburger et al. Experimental evidence for interatomic Coulombic decay in Ne clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 203401 (2003).

Jahnke, T. et al. Experimental observation of interatomic Coulombic decay in neon dimers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 163401 (2004).

Öhrwall, G. et al. Femtosecond interatomic Coulombic decay in free neon clusters: large lifetime differences between surface and bulk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 173401 (2004).

Matsumoto, J. et al. Asymmetry in multiple-electron capture revealed by radiative charge transfer in ar dimers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 263202 (2010).

Titze, J. et al. Ionization dynamics of helium dimers in fast collisions with He++. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 033201 (2011).

Sakai, K. et al. Electron-transfer-mediated decay and interatomic Coulombic decay from the triply ionized states in argon dimers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 033401 (2011).

O’Keeffe, P. et al. The role of the partner atom and resonant excitation energy in interatomic coulombic decay in rare gas dimers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1797 (2013).

Iskandar, W. et al. Atomic site-sensitive processes in low energy ion-dimer collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 143201 (2014).

Fruhling, U. et al. Time-resolved studies of interatomic Coulombic decay. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 204, 237 (2015).

Iskandar, W. Interatomic Coulombic decay as a new source of low energy electrons in slow ion-dimer collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 033201 (2015).

Ren Xueguang et al. Direct evidence of two interatomic relaxation mechanisms in argon dimers ionized by electron impact. Nat. Commun. 7, 11093 (2016).

Wu, J. et al. Structures of N2Ar, O2Ar, and O2Xe dimers studied by Coulomb explosion imaging. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 104308 (2012).

Wu, J. et al. Strong field multiple ionization as a route to electron dynamics in a van der Waals cluster. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 083003 (2013).

Wu Chengyin et al. Communication: Determining the structure of the N2Ar van der Waals complex with laser-based channel-selected Coulomb explosion. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 141101 (2014).

Trinter, F. et al. Resonant Auger decay driving intermolecular Coulombic decay in molecular dimers. Nature 505, 664 (2014).

Ding Xiaoyan et al. Ultrafast dissociation of Metastable CO2+ in a dimer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 153001 (2017).

Mery, A. et al. Role of a neighbor ion in the fragmentation dynamics of covalent molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 233402 (2017).

Chiang, Ying-Chih et al. Molecular-bond breaking induced by interatomic decay processes. Phys. Rev. A 100, 052701 (2019).

Jahnke, T. et al. Ultrafast energy transfer between water molecules. Nat. Phys. 6, 139 (2010).

Zettergren, H. et al. Formations of dumbbell C118 and C119 inside clusters of C60 molecules by collision with α particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 185501 (2013).

Delaunay, R. et al. Molecular growth inside of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon clusters induced by ion collisions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 1536 (2015).

Xueguang, Ren et al. Experimental evidence for ultrafast intermolecular relaxation processes in hydrated biomolecules. Nat. Phys. 14, 1062 (2018).

Unger, Isaak et al. Observation of electron-transfer-mediated decay in aqueous solution. Nat. Chem. 9, 708 (2017).

Yan, S. et al. Interatomic relaxation processes induced in neon dimers by electron-impact ionization. Phys. Rev. A 97, 010701(R) (2018).

Xu, S. et al. Damaging intermolecular energy and proton transfer processes in alpha-particle-irradiated hydrogen-bonded systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 17023 (2018).

Richter, Clemens et al. Competition between proton transfer and intermolecular Coulombic decay in water. Nat. Commun. 9, 4988 (2018).

Bart, Oostenrijk et al. The role of charge and proton transfer in fragmentation of hydrogen-bonded nanosystems: the breakup of ammonia clusters upon single photon multi-ionization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 932 (2018).

Löwdin, P. O. Proton tunneling in DNA and its biological implications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 35, 724 (1963).

Chojnacki, Henryk Special issue on proton transfer processes. Int. J. mol. Sci. 4, 408 (2003).

Jacquemin, D. et al. Assessing the importance of proton transfer reactions in DNA. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2467 (2014).

Panwang Zhou & Han, Keli Unraveling the detailed mechanism of excited-state proton transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1681 (2018).

Zhu, X. L. et al. Probing the geometry of Ar2N2 cluster by 1 MeV Ne8+ ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 408, 42 (2017).

Broström, L. et al. The visible photoabsorption spectrum and potential curves of ArN+. J. Chem. Phys. 94, 2734 (1991).

Lundqvist, M. et al. Doppler-free kinetic energy release spectrum of N2 2+. J. Phys. B 29, 1489 (1996).

Mathur, D. Long-lived, doubly charged diatomic and triatomic molecular ions. J. Phys. B 28, 3415 (1995).

Riss, U. V. & Meyer, H.-D. Calculation of resonance energies and widths using the complex absorbing potential method. J. Phys. B 26, 4503–4535 (1993).

Ma, X. et al. Electron emission from single-electron capture with simultaneous single-ionization reactions in 30-keV/u He2+-on-argon collisions. Phys. Rev. A 83, 052707 (2011).

Dörner, R. et al. Cold target recoil ion momentum spectroscopy: a ‘momentum microscope’ to view atomic collision dynamics. Phys. Rep. 330, 95 (2000).

Ullrich, J. et al. Recoil-ion and electron momentum spectroscopy: reaction-microscopes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 1463 (2003).

Krebs, S. & Buenker, R. J. A new table-direct configuration interaction method for the evaluation of Hamiltonian matrix elements in a basis of linear combinations of spin-adapted functions. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 5613 (1995).

Knowles, P. J. et al. An efficient second-order MC SCF method for long configuration expansions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 115, 259 (1985).

Werner, H. J. et al. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 242 (2012).

Werner, H. J. et al. MOLPRO, A Package of Ab Initio Programs. (Cardiff University, Cardiff, U.K. 2012).

Qiu, B. & Xiulin, R. Molecular dynamics simulations of lattice thermal conductivity of bismuth telluride using two-body interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 80, 165203 (2009).

Moiseyev, N. Quantum theory of resonances: calculating energies, widths and cross-sections by complex scaling. Phys. Rep. 302, 212 (1998).

Lin, X. H. et al. Theoretical study of resonances formed in low-energy Li−+H collisions. Chem. Phys. 522, 10 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2017YFA0402300, 2017YFA0402400, and 2017YFA0403200), the Science Challenge Project (Grant No. TZ2016005), and the NSFC of China (Grant Nos. 11934004 and 11974358). The authors thank the staff of 320 kV platform for their technical support. The authors acknowledge the helpful discussions with Dr. Bennaceur Najjari and suggestions from Dr. Michael Schulz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.M. and X.L.Z. designed the experiment. X.L.Z., W.T.F., D.L.G., Y.G., S.F.Z., D.M.Z., J.W.X., D.P.D., and B.H. performed the experiment. X.L.Z. and S.C.Y. analyzed the experimental data. X.Q.H., Y.G.P., Y.W., and J.G.W. carried out the theoretical calculations and analysis. X.M., X.L.Z., X.Q.H., A.C., and Y.W. contributed to the interpretation of the data. The manuscript was written by X.M., X.L.Z., X.Q.H., and Y.W. All authors discussed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Hu, X., Yan, S. et al. Heavy N+ ion transfer in doubly charged N2Ar van der Waals cluster. Nat Commun 11, 2987 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16749-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16749-w

This article is cited by

-

Tunnelling of electrons via the neighboring atom

Light: Science & Applications (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.