Abstract

Employment of sulfoxides as electrophiles in cross-coupling reactions remains underexplored. Herein we report a transition-metal-free cross-coupling strategy utilizing aryl(heteroaryl) methyl sulfoxides and alcohols to afford alkyl aryl(heteroaryl) ethers. Two drug molecules were successfully prepared using this protocol as a key step, emphasizing its potential utility in medicinal chemistry. A DFT computational study suggests that the reaction proceeds via initial addition of the alkoxide to the sulfoxide. This adduct facilitates further intramolecular addition of the alkoxide to the aromatic ring wherein charge on the aromatic system is stabilized by the nearby potassium cation. Rate-determining fragmentation then delivers methyl sulfenate and the aryl or heteroaryl ether. This study establishes the feasibility of nucleophilic addition to an appended sulfoxide as a means to form a bond to aryl(heteroaryl) systems and this modality is expected to find use with many other electrophiles and nucleophiles leading to new cross-coupling processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

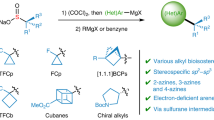

Though cross-coupling reactions have become tremendously enabling in the past decades, further expansion of the electrophilic partners beyond conventional aryl halides, sulfonates, or carbonates, remains a considerable challenge1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The use of organosulfur compounds in cross-coupling is a new horizon that merits study due to their availability, chemical robustness, and structural versatility11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. To date, a number of cross-coupling reactions utilizing aryl sulfides or sulfones have been reported, as exemplified by the well-known Liebeskind-Srogl cross-coupling reaction16,19,20,22. In sharp contrast, employment of sulfoxides as electrophiles in transition-metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions via C-S bond activation remains rare (Fig. 1).

a Nickel-catalyzed Kumada coupling reaction of diaryl sulfoxides. b Palladium-catalyzed Sonogashira coupling reaction of diaryl sulfoxides. c Palladium-catalyzed borylation of diaryl sulfoxides. d Buchwald-Hartwig amination of diaryl sulfoxides and amines. e Nickel-catalyzed Negishi coupling reaction of aryl methyl sulfoxides. f This work: transition-metal-free formal cross-coupling of aryl methyl sulfoxides and alcohols.

In 1979, Wenkert and coworkers pioneered the first nickel-catalyzed Kumada coupling reaction employing diaryl sulfoxides as electrophiles (Fig. 1a)23. In 2017, the Yorimitsu group reported a palladium-catalyzed Sonogashira coupling employing diaryl sulfoxides as electrophilic partners (Fig. 1b)24. The same group also described a second generation Buchwald-type palladacycle precatalyst that facilitated the double borylation of diaryl sulfoxides with diborane species (Fig. 1c)25. Both of the protocols shared some drawbacks, primarily low yields and limited functional group tolerance. Very recently, the same group reported a Buchwald-Hartwig amination between diaryl sulfoxides and amines catalyzed by an N-heterocyclic carbene-ligated palladium complex (Pd/SingaCycle-A1) (Fig. 1d)26. They noticed that aryl methyl sulfoxides, unfortunately, suffered from very low yields. The first systematic study employing alkyl aryl sulfoxides as electrophiles emerged in 2017 from the Yorimitsu group27. They demonstrated that synthetically accessible aryl methyl sulfoxides could undergo nickel-catalyzed oxidative addition of C–S bond, which was compatible with a Negishi coupling procedure to afford biaryl products (Fig. 1e). However, considerable effort is needed to separate the homocoupling byproducts of the zinc reagents from the desired heterocoupling products. In reports of aryl sulfide cross-couplings, selected examples are also shown where the corresponding sulfoxides can act as the electrophilic partner28,29,30.

In general, the previous transition-metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of sulfoxides with different nucleophiles rely on transition metal oxidative addition to the C–S bond23,24,25,26,27. Transition-metal catalysts can require complex ligands, which may add significantly to the overall costs. In addition, the removal of trace transition metals in pharmaceutical and other applications remains a challenge31,32,33,34. In contrast, transition-metal-free cross-coupling strategies can overcome many of these limitations35,36. Some Friedel-Crafts-type protocols fall into this category, but suffer from limited substrate scope (electron rich arenes) and limited control over the reactive position on a given aromatic substrate.

We envisioned that a neglected S-tetracovalent dialkoxyl alkyl aryl intermediate (Fig. 1f, see key intermediate), which was pioneered by Martin group several decades ago37,38,39, could potentially be utilized to activate the C–S bond, facilitating alkyl aryl sulfoxides as electrophilic coupling partners in the subsequent transition-metal-free coupling reactions with alcohols. This strategy would allow selective conversion of thio or sulfoxide groups to alkoxy groups. Furthermore, the utilization of sulfoxides in coupling reactions represents an alternative and complimentary pathway to conventional partners, such as aryl (pseudo)halides or alcohols, since methyl sulfoxides are prepared from thiophenol derivatives, which are manufactured from benzenesulfonic acid or benzenesulfonyl chloride, independent of aryl (pseudo)halides or alcohols. Herein, we report a transition-metal-free cross-coupling strategy enabled by a base-substrate interaction mode and apply it to the reaction of aryl methyl sulfoxides with alcohols to afford a general and complementary entry to alkyl aryl ethers (Fig. 1f).

Results

Optimization study

Readily accessible methyl 2-naphthyl sulfoxide (1a) which possess no electronic or steric bias was chosen as the model substrate for the study (Table 1). The investigation was initialized by treating 1a with three methoxide bases (LiOMe, NaOMe and KOMe) in 2-Me-THF at 110 °C for 12 h (Table 1, entries 1–3). Use of KOMe as base as well as the nucleophile afforded product 3a in 12% yield. To improve reactivity, four different solvents [toluene, dimethoxyethane (DME), cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME), and dioxane]) were examined using 1a and KOMe (Table 1, entries 4–7). DME was the best solvent, generating 3a in 33% yield (Table 1, entry 5). We next probed the roles of KOMe by using MeOH (2a) in the presence of different potassium bases [KOtBu, K2CO3, KOH, KN(SiMe3)2, Table 1, entries 8–11]. Notably, the yield of 3a increased to 67% when KOtBu was employed as the base (Table 1, entry 8). Furthermore, the potential byproduct, 2-naphthyl tert-butyl ether, was observed only in trace amounts; presumably, the steric hindrance of OtBu limits its participation as a nucleophile. In the optimization, concentration was determined to be a key factor. When the concentration of the reaction was elevated to 0.5 M, product 3a could be prepared in an optimal 95% yield (Table 1, entry 12). However, the yield of 3a slightly dropped to 91% when the concentration was raised further to 1.0 M (Table 1, entry 13). The amounts of both base and nucleophile could be successfully decreased to 2 equivalents, and 3a was still obtained in 94% assay yield, 90% isolated yield (Table 1, entry 14). Further decreasing the equivalents of either component or the temperature resulted in lower yields (Table 1, entries 15–17). Therefore, the optimal transition-metal-free cross-coupling reaction was 1 equivalent of 1a as electrophile, 2 equivalents of methanol as nucleophile, and 2 equivalents of KOtBu as base in DME (0.5 M) at 110 °C for 12 h.

Substrate scope

Having identified optimal reaction conditions, we next explored the scope of substrates of aliphatic alcohols (Fig. 2). Methanol (2a) and ethanol (2b) were successfully utilized as coupling partners, generating 3a and 3b in 90% and 93% yield respectively. A secondary alcohol, isopropanol (2c), furnished the corresponding product 3c in good yield (82%). Aliphatic alcohols possessing phenyl substituents either at the α- or γ- position were well tolerated, providing 3d and 3e in 61% and 86% yield, respectively. The reactions proceeded smoothly between 1a and alcohols bearing cyclic substituents (2f, 2h), affording the corresponding products in good to excellent yields. Even sterically hindered 1-adamantylmethanol (2h) could be utilized and produced 3h in 80% yield. Moreover, alkyl alcohols with ether or amine functional groups were well tolerated and led to the formation of the desired products 3i-l in excellent yields. Remarkably, the potentially competitive amination did not occur at all with either primary amine 2k or secondary amine 2l. Our protocol could be utilized to functionalize more complex structures including natural products to afford 3m and 3n in excellent yields.

Next, the aryl group of the methyl sulfoxides was surveyed when cyclohexylethan-1-ol (2g) was employed as cross-coupling partner (Fig. 3). Phenyl methyl sulfoxide (1b) could successfully couple with 2g to afford the corresponding 4a in 76% yield under slightly modified conditions. Methyl sulfoxides bearing electron-withdrawing substituents such as cyano or trifluoromethyl groups underwent the cross-coupling reaction to afford compounds 4b and 4c in excellent yields. Substrates with electron-donating groups reacted more sluggishly; even so, 4d and 4e were successfully prepared using our method in modest to good yields. It is noteworthy that the para-thiomethyl group barely reacted, in contrast to prior reports involving transition metal catalysts23,28,29,30, allowing the formation of 4e and highlighting the unique chemoselectivity of our protocol. Steric hindrance on the aryl sulfoxide portion exerted negligible influence on our protocol as evidenced by the 1-naphthyl derivative 4f forming in 94% yield. Methyl sulfoxides possessing a polymerizable vinyl group (1h) or and electrophilic carbonyl group (1i) were also compatible, albeit giving 4g and 4h in modest yields. Alkyl heteroaryl ethers are ubiquitous in biologically relevant compounds40. Remarkably, a range of heteroaryl groups exhibited good to excellent compatibility under the optimal conditions; pyridyl (4i, 4j, 4k), isoquinolyl (4l), imidazolyl (4m), pyrimidinyl (4n), benzoimidazolyl (4o) as well as quinolyl (4p-t) ethers could be obtained in 66–99% yields. A small number of pyridyl sulfoxides have been found to undergo substitution with alkoxides, but reduction was an accompanying product41,42. Of note, bromo- or iodo-substituents on 4r-t were compatible with this method, providing a means for later modification via orthogonal transition-metal catalyzed coupling strategies. Significantly, this protocol could even be utilized to directly derivatize 2-(methylsulfinyl)-4-(2-thiophenyl)-6- (trifluoromethyl)pyrimidine (1v), a patented compound with anti-apoptosis bioactivity43, to deliver 4u in 72% yield. To establish the scalability of our transition-metal-free coupling procedure, a gram-scale reaction with 1q (5.5 mmol, 1.05 g) and 2g (11.0 mmol, 1.41 g) was performed, affording 4p in excellent yield (99%, 1.48 g).

aUnless noted, all reactions were conducted with 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 g (0.4 mmol), KOtBu (0.4 mmol) in DME (0.4 mL) under argon atmosphere at 110 °C for 12 h. b2g (3.0 equiv), KOtBu (3.0 equiv) at 110 °C for 24 h. c2g (3.0 equiv), KOtBu (3.0 equiv). d40 °C; e2g (3.0 equiv), KOtBu (4.0 equiv) at 100 °C for 30 h. fLarge scale reaction: 1q (5.5 mmol), 2g (11.0 mmol), KOtBu (11.0 mmol) in DME (11.0 mL) under argon atmosphere at 110 °C for 12 h. g1u (4.0 equiv), 2g (1.0 equiv), KOtBu (2.0 equiv) at 40 °C for 48 h.

Synthetic applications

To illustrate the potential utility of a transition-metal free coupling reaction of aryl methyl sulfoxides with alcohols in medicinal chemistry and drug development, two drug candidates have been prepared employing this method as the key step (Fig. 4). A sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator 6e, which is currently in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of multiple sclerosis44, could be synthesized in 5 steps and 20% overall yield. Notably, no transition metals are utilized in the entire route, simplifying the drug purification process. Another patented compound, opioid delta receptor agonist 7c45, could be generated in only 3 steps and 61% overall yield using our highly chemoselective transition-metal free coupling strategy as the key step.

From the standpoint of atom economy, aryl methyl sulfoxides are the most appealing of sulfoxide coupling partners. Nevertheless, other alkyl aryl sulfoxides were also explored (Table 2). Ethyl 2-naphtyl sulfoxide (5a) proved to be a suitable coupling partner, despite affording 3a in lower yield (Table 2, 5a). As expected, the other three alkyl sulfoxides under investigation (5b–d) only generated trace amounts of 3a, presumably owing to rapid formation of sulfenate anions after attack of methoxide on the sulfur46,47,48 (Table 2, 5b–5d).

To understand the mechanism, a series of control experiments were performed (Table 3). When 2.0 equiv of TEMPO was introduced under the standard reaction conditions, the yield of 3a was not significantly affected (see Supplementary Information for details), which points away from a radical pathway. Next, KOtBu was replaced by two other tert-butoxide bases (LiOtBu, NaOtBu) in the transition-metal-free cross-coupling protocol, with the rest of the conditions kept the same. Despite the similar basicity of these reagents, the yields of 3a were dramatically decreased, which illustrates the crucial role of the potassium cation (Table 3, entries 1–2). To further confirm the effect, 2.0 equivalents 18-crown-6 were introduced into the otherwise standard conditions, and the yield of 3a dropped precipitously to 5% (Table 3, entry 3). In a subsequent study, 2.0 equivalents of potassium fluoride added to the reactions with LiOtBu or NaOtBu restored the reactivity providing 63% and 27% yield, respectively (Table 3, entries 4–5). These control experiments support a pivotal role of potassium cation in the transition-metal-free cross-coupling49,50. Hence, a computational study was conducted to fully understand this unusual C-S bond activation mode for methyl sulfoxides that does not require a transition metal catalyst.

Mechanistic studies

Computational studies focused on the reaction of 1a with methoxide using different cations (K, Na and Li). DFT calculations were performed using Gaussian 09. All geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency calculations of stationary points and transition states (TSs) were carried out at the B3LYP level of theory with 6-31+G(d) basis set for all atoms. Single point energies and solvent effects in 1,4-dioxane were computed at the M06-2X level of theory with 6-31+G(d,p) basis set for all atoms, using the gas-phase optimized structures. Solvation energies were calculated by a self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) using the SMD solvation model.

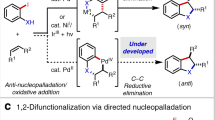

Several possible mechanisms were taken into consideration (Fig. 5). The first proposal (Fig. 5a), involves a SNAr reaction between the aryl methyl sulfoxide and the alkoxide, initiated by a π-cation interaction between the potassium and the aromatic ring51,52,53. A second proposal (Fig. 5b) proceeds via concerted addition of the alkoxide and elimination of the methyl sulfoxide group. The third mechanistic possibility involves nucleophilic addition of the alkoxide to the methyl sulfoxide facilitated by coordination of the potassium cation to the aromatic ring and the oxygen from the sulfoxide group. The resultant intermediate can subsequently undergo cyclization via attack of the oxygen atom on the ipso carbon. The final step entails the elimination of the methyl sulfenate to afford the desired product (Fig. 5c).

The first mechanistic proposal was quickly found to be untenable due to far more favorable coordination of the cation to the sulfoxide oxygen rather than via a π-cation complex. Intermediates and transition states for the second mechanistic possibility were located. However, the computational energies indicate that the potassium counterion should decrease the reactivity relative to sodium and lithium (see Supplementary Fig. 1), which is the opposite of what was observed experimentally.

In contrast, the third mechanism (Fig. 5c) accounts for the experimentally observed cation effect (Fig. 6). Calculations suggest that the reaction proceeds via a nucleophilic attack of the alkoxide to the sulfoxide, which will lead to coordination of the counterion with the C1 carbon and formation of a three membered ring via attack of the alkoxy oxygen to the ipso carbon of 1a to afford INT1. This intermediate can then undergo an elimination step via TS1 to afford the desired product and methyl sulfenate. The energy barrier to obtain the desired product is significantly lower for potassium than for sodium or lithium. Calculations suggest that the nature of the cation will affect both the stability of INT1 and the subsequent elimination of the methyl sulfenate. Experimental observations showed that the use of LiOtBu completely inhibits reactivity, and that NaOtBu significantly decreases the yield (Table 3, entries 1–2), further supporting the computational findings. Since this mechanism relies on initial nucleophilic attack of the sulfoxide, it also consistent with more electrophilic substrates reacting more quickly (Table 2, 5b and 5c) than those with electron donating groups (Table 2, 5d). For heterocycles with a nitrogen adjacent to the sulfoxide (4i, 4j, 4m, 4n, 4o, 4u), reactivity may be further assisted by bidentate coordination of the potassium to the heterocyclic nitrogen and the sulfoxide oxygen. However, the lack of any distinct trends in the outcomes for these substrates relative to heterocycles with more distal nitrogens (4k, 4l, 4p, 4q, 4r, 4s, 4t) indicates that this effect does not predominate.

Discussion

In summary, a unique transition-metal-free cross-coupling protocol utilizing aryl methyl sulfoxides as electrophilic partners with alcohols to afford alkyl aryl ethers is described. An array of functional groups is well tolerated, and the method can be used for late-stage functionalization of natural products and pharmaceuticals. The methyl sulfoxides utilized as coupling partners in our protocol were generally prepared by methylation of corresponding thiophenol derivatives, followed by oxidation by NaIO4 or m-CPBA. Considering that thiophenol derivatives are typically manufactured by reduction of benzenesulfonic acid or benzenesulfonyl chloride, the method developed herein provides orthogonal entries relative to halides or alcohols, which permits different functional group compatibility and different substitution patterns. The successful application of the transition-metal free coupling reaction reported herein in drug syntheses and derivatization highlights its potential utility in medicinal chemistry as well as drug development. Both experimental results and a DFT-based computational study suggest that the reaction proceeds via a nucleophilic addition of the alkoxide to the sulfoxide accompanied by a cyclization. Subsequently, the alkoxide migrates to the ipso carbon while eliminating the methyl sulfenate. The dramatic impact of the cation on the reactivity arises both from greater stabilization of INT1 via association with the C1 carbon and enhanced ability to fragment via TS1. These results wherein an electrophilic partner is activated by addition of a nucleophile that both enhances its ability as leaving group and activates the aromatic substrate via coordination of a counterion open up possibilities for electrophile activation and coupling in general. The concepts described herein also provide a basis for the construction of systems to allow transformations of organosulfur compounds in other contexts.

Methods

General procedure for catalysis

To an oven-dried microwave vial equipped with a stir bar was added KOtBu (44.9 mg, 0.4 mmol, 2 equiv), and 2-methanesulfinyl-naphthalene (38.0 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) under argon atmosphere in a glove box. DME (0.4 mL) was added to the vial by syringe. The microwave vial was sealed and removed from the glove box. Then, methanol (16.2 μL, 0.4 mmol, 2 equiv) was added by syringe under argon atmosphere. Note that solid and viscous oil alcohols were added to the reaction vial prior to KOtBu. The reaction mixture was heated to 110 °C in an oil bath and stirred for 12 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the sealed vial was cooled to room temperature, and opened to air. The reaction mixture was passed through a short pad of silica gel. The pad was then rinsed with 10:1 dichloromethane:methanol. The resulting solution was subjected to reduced pressure to remove the volatile materials and yielded a viscous oil. The residue was purified by flash chromatography as outlined below.

Data availability

Experimental procedure and characterization data of new compounds are available within the Supplementary Information. Any further relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Tamao, K. & Miyaura, N. Cross-Coupling Reactions: A Practical Guide (Heidelberg, S. V. B., 2002).

Beletskaya, I. P. & Cheprakov, A. V. Metal Complexes as Catalysts for C-C Cross-Coupling Reactions (Elsevier Ltd., 2003).

Jana, R., Pathak, T. P. & Sigman, M. S. Advances in transition metal (Pd, Ni, Fe)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions using alkyl-organometallics as reaction partners. Chem. Rev. 111, 1417–1492 (2011).

So, C. M. & Kwong, F. Y. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of aryl mesylates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4963–4972 (2011).

Meijere, A. D. & Diederich, F. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions (Wiley, 2004).

Hassan, J., Sévignon, M., Gozzi, C., Schulz, E. & Lemaire, M. Aryl-aryl bond formation one century after the discovery of the Ullmann reaction. Chem. Rev. 102, 1359–1469 (2002).

Alberico, D., Scott, M. E. & Lautens, M. Aryl-aryl bond formation by transtion-metal-catalyzed direct arylation. Chem. Rev. 107, 174–238 (2007).

Suzuki, A. Cross-coupling reactions of organoboranes: an easy way to construct C-C Bonds (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6722–6737 (2011).

Henri, D. Cross Coupling and Heck-Type Reactions (Thieme, 2013).

Nishihara, Y., Masayuki, O., Jiao, J. & Chang, N. H. Applied Cross-Coupling Reactions (Springer, 2013).

Sugimura, H., Okamura, H., Miura, M., Yoshida, M. & Takei, H. The coupling reaction of Grignard reagents with unsaturated sulfides catalyzed by nickel complexes. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi 3, 416–424 (1985).

Naso, F. Stereospecific synthesis of olefins through sequential cross-coupling reactions. Pure Appl. Chem. 60, 79–88 (1988).

Luh, T.-Y. & Ni, Z.-J. Transition-metal-mediated C-S bond cleavage reactions. Synthesis 2, 89–103 (1990).

Luh, T.-Y. New synthetc applications of the dithioacetal functionality. Acc. Chem. Res. 24, 257–263 (1991).

Fiandanese, V. Sequential cross-coupling reactions as a versatile synthetic tool. Pure Appl. Chem. 62, 1987–1992 (1990).

Dubbaka, S. R. & Vogel, P. Organosulfur compounds: electrophilic reagents in transition-metal-catalyzed carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 7674–7684 (2005).

Prokopcova, H. & Kappe, C. O. Copper-catalyzed C-C coupling of thiol esters and boronic acids under aerobic conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3674–3676 (2008).

Wang, L., He, W. & Yu, Z. Transition-metal mediated carbon-sulfur bond activation and transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 599–621 (2013).

Modha, S. G., Mehta, V. P. & van der Eycken, E. V. Transition metal-catalyzed C-C bond formation via C-S bond cleavage: an overview. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 5042–5055 (2013).

Pan, F. & Shi, Z. J. Recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed C–S activation: from thioester to (Hetero)aryl thioether. ACS Catal. 4, 280–288 (2013).

Gao, K. et al. Cross-coupling of aryl sulfides powered by N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. J. Syn. Org. Chem. Jpn. 74, 1119–1126 (2016).

Prokopcova, H. & Kappe, C. O. The Liebeskind-Srogl C-C cross-coupling reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2276–2286 (2009).

Wenkert, E., Ferreira, T. W. & Michelotti, E. L. Nickel-induced conversion of carbon-sulphur into carbon-carbon bonds. One-step transformations of enol sulphides into olefins and benzenthiol derivatives into alkylarenes and biaryls. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39790000637 (1979).

Yorimitsu, H., Yoshida, Y. & Nogi, K. C–S bond alkynylation of diaryl sulfoxides with terminal alkynes by means of a palladium–NHC catalyst. Synlett 28, 2561–2564 (2017).

Yorimitsu, H., Saito, H. & Nogi, K. Palladium-catalyzed double borylation of diaryl sulfoxides with diboron. Synthesis 49, 4769–4774 (2017).

Yoshida, Y., Otsuka, S., Nogi, K. & Yorimitsu, H. Palladium-catalyzed amination of aryl sulfoxides. Org. Lett. 20, 1134–1137 (2018).

Yamamoto, K., Otsuka, S., Nogi, K. & Yorimitsu, H. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of aryl sulfoxides with arylzinc reagents: when the leaving group is an oxidant. ACS Catal. 7, 7623–7628 (2017).

Someya, C. I., Weidauer, M. & Enthaler, S. Nickel-catalyzed C(sp2)–C(sp2) cross coupling reactions of sulfur-functionalities and Grignard reagents. Catal. Lett. 143, 424–431 (2013).

Uetake, Y., Niwa, T. & Hosoya, T. Rhodium-catalyzed ipso-borylation of alkylthioarenes via C-S bond cleavage. Org. Lett. 18, 2758–2761 (2016).

Yang, J., Xiao, J., Chen, T., Yin, S. F. & Han, L. B. Efficient nickel-catalyzed phosphinylation of C-S bonds forming C-P bonds. Chem. Commun. 52, 12233–12236 (2016).

Magano, J. & Dunetz, J. R. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Couplings in Process Chemistry (Wiley, 2014).

Ibigbami, T. B., Dawodu, F. A. & Akinyeye, O. J. Removal of heavy metals from pharmaceutical industrial wastewater effluent by combination of adsorption and chemical precipitation methods. J. Arg. Food Chem. 4, 24–32 (2016).

Reichert, U. Implementing the Guideline on the Specification Limits for Residues of Metal Catalysts or Metal Reagents. MSc, Uni. of Bonn (2009).

Türck, M. & Bern, P. M. Elemental Impurities in Substances for Pharmaceutical Use – Current Trends in Pharmacopoeial Testing [Powerpoint presentation] (2011).

Sun, C. L. & Shi, Z. J. Transition-metal-free coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 114, 9219–9280 (2014).

Qin, Y., Zhu, L. & Luo, S. Organocatalysis in inert C-H bond functionalization. Chem. Rev. 117, 9433–9520 (2017).

Kaplan, L. J. & Martin, J. C. Sulfuranes. IX. sulfuranyl substituent parameters. Substituent effects on the reactivity of dialkoxydiarylsulfuranes in the dehydration of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 793–798 (1973).

Franz, J. A. & Martin, J. C. Surfuranes. X. A reagent for the facile cleavage of secondary amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 2017–2019 (1973).

William, M. D., Mindaugas, S., Thomas, E. S., William, L. & Robert, A. S. Versatile C(sp2)-C(sp3) ligand coupling of sulfoxides for the enantioselective synthesis of diarylalkanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10013–10016 (2016).

Wang, J. M. & Hou, T. J. Drug and drug candidate building block analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 55–67 (2010).

Furukawa, N., Ogawa, S., Kawai, T. & Oae, S. Selective ipso-Substitution in pyridine ring and its application for the synthesis of macrocylces containing both oxa- and thia-Bridges. Tetrahedron Lett. 24, 3243–3246 (1983).

Furukawa, N., Ogawa, S. & Kawai, T. ipso-Substitution of a sulphinyl or sulphonyl group attached to pyridine rings and its application for the synthesis of macrocycles. J. Chem. Soc. 8, 1839–1845 (1984).

Zhang, Z. et al. Apoptosis inhibitors [Patent] (China, 2018).

Thomas, J. et al. S1P modulating agents [Patent] (U.S., 2012).

Dondio, G., Macecchini, S. & Raveglia, L. F. Novel method & compounds [Patent] (Italy, 2004).

O’Donnell, J. S. & Schwan, A. L. Generation, structure and reactions of sulfenic acid anions. J. Sulfur Chem. 25, 183–211 (2004).

Maitro, G., Prestat, G., Madec, D. & Poli, G. An escapade in the world of sulfenate anions: generation, reactivity and applications in Domino processes. Tetrahedron 21, 1075–1084 (2010).

Schwan, A. L. & Söderman, S. C. Discoveries in sulfenic acid anion chemistry. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 188, 275–286 (2013).

Sha, S. C. et al. Cation-π interactions in the benzylic arylation of toluenes with bimetallic catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12415–12423 (2018).

Kim, B. et al. Distal stereocontrol using guanidinylated peptides as multifunctional ligands: desymmetrization of diarylmethanes via Ullman cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7939–7945 (2016).

Dougherty, D. A. The Cation-π Interaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 885–893 (2013).

Kumar, K. et al. Cation-π interactions in protein-ligand binding: theory and data-mining reveal different roles for lysine and arginine. Chem. Sci. 9, 2655–2665 (2018).

Marshall, M. S., Steele, R. P., Thanthiriwatte, K. S. & Sherrill, C. D. Potential energy curves for cation-π interactions: off-axis configurations are also attractive. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 13628–13632 (2009).

Acknowledgements

T.J. thanks Shenzhen Nobel Prize Scientists Laboratory Project (C17783101), the Science and Technology Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (JCYJ20180302180256215), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (2020B121201002) for financial support. SUSTech is gratefully acknowledged for providing startup funds to T.J. (Y01216129). M.C.K. thanks the NIH (GM131902) for financial support and XSEDE (TG-CHE120052) for computational support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L., Q.L., H.Z., Q.L. and S.S. performed the experiments. Y.N.-O. carried out computational study. M.C.K. directed the part of computational study. T.J. and M.C.K. conceived and directed the project and wrote this paper. All authors approved the submission of the manuscript. G.L. and Y.N.-O. contributed equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Peizhong Xie and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Nieves-Quinones, Y., Zhang, H. et al. Transition-metal-free formal cross-coupling of aryl methyl sulfoxides and alcohols via nucleophilic activation of C-S bond. Nat Commun 11, 2890 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16713-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16713-8

This article is cited by

-

A review on copper-based nanoparticles as a catalyst: synthesis and applications in coupling reactions

Journal of Materials Science (2024)

-

Electronic structure of dimethyl sulfoxide homologues

Russian Chemical Bulletin (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.