Abstract

Despite the conserved essential function of centromeres, centromeric DNA itself is not conserved. The histone-H3 variant, CENP-A, is the epigenetic mark that specifies centromere identity. Paradoxically, CENP-A normally assembles on particular sequences at specific genomic locations. To gain insight into the specification of complex centromeres, here we take an evolutionary approach, fully assembling genomes and centromeres of related fission yeasts. Centromere domain organization, but not sequence, is conserved between Schizosaccharomyces pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus with a central CENP-ACnp1 domain flanked by heterochromatic outer-repeat regions. Conserved syntenic clusters of tRNA genes and 5S rRNA genes occur across the centromeres of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus, suggesting conserved function. Interestingly, nonhomologous centromere central-core sequences from S. octosporus and S. cryophilus are recognized in S. pombe, resulting in cross-species establishment of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin and functional kinetochores. Therefore, despite the lack of sequence conservation, Schizosaccharomyces centromere DNA possesses intrinsic conserved properties that promote assembly of CENP-A chromatin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Centromeres are the chromosomal regions upon which kinetochores assemble to mediate accurate chromosome segregation. Evidence suggests that both genetic and epigenetic influences define centromere identity1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Neocentromere formation at new locations lacking homology to centromeres10 and the inactivation of one centromere of a dicentric chromosome despite it retaining centromeric sequences11 indicate that centromere sequences are neither necessary nor sufficient for centromere assembly1,7,9. CENP-A is found at all active centromeres and is the epigenetic mark that specifies centromere identity1,7,9. Artificial tethering of CENP-A or CENP-A loading factors at non-centromeric locations on metazoan chromosomes is sufficient to trigger kinetochore assembly5,12. Thus, it is specialized chromatin rather than primary sequences of centromeric DNA that determines where kinetochores and hence functional centromeres are assembled. On the contrary, however, CENP-A is generally found on particular sequences in any given organism1,2,4 and naked repetitive centromere DNA such as alpha-satellite DNA can provide a substrate for the de novo assembly of functional centromeres when introduced into human cells1,2,3,4. These observations suggest that, despite the lack of conservation between species, centromere sequences possess properties that make them attractive for assembly of CENP-A chromatin.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a paradigm for dissecting complex regional centromere function, has demarcated centromeres (35–110 kb) with a central domain assembled in CENP-ACnp1 chromatin, flanked by outer-repeat elements assembled in RNA interference-dependent heterochromatin, in which histone-H3 is methylated on lysine-9 (H3K9)13,14,15,16. Heterochromatin is required for establishment but not maintenance of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin6,17. We have proposed that it is not the sequence per se of S. pombe central-core that is key in its ability to establish CENP-A chromatin but the properties programmed by it18,19.

To investigate whether these properties are conserved, here we completely assemble the sequence across centromeres of other Schizosaccharomyces species and test their cross-species functionality. We show that although Schizosaccharomyces centromeres are not conserved in sequence, those of Schizosaccharomyces octosporus and Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus share with S. pombe a conserved organization of a central domain assembled in CENP-ACnp1 chromatin, flanked by outer repeats assembled in heterochromatin. Syntenic clusters of tRNA and 5S-rRNA genes are present across S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres, further emphasizing their conserved organization. By introducing minichromosomes bearing central domain sequences from S. octosporus and S. cryophilus into S. pombe, we demonstrate that these nonhomologous centromere sequences can be recognized between divergent species, allowing the establishment of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin and functional centromeres. These observations indicate that centromere DNA possesses conserved properties that promote the establishment of CENP-A chromatin.

Results

Conserved organization of fission yeast centromeres

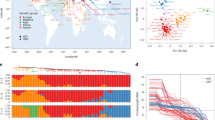

Long-read (PacBio) sequencing permitted complete assembly of the genomes across centromeres of S. octosporus (11.9 Mb) and S. cryophilus (12.0 Mb), extending genome sequences20 to telomeric or subtelomeric repeats, or rDNA arrays (Supplementary Figs. 1–3, Supplementary Data 1, 2). Consistent with their closer evolutionary relationship20,21,22, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus (32 My separation, compared with 119 My separation from S. pombe) exhibit greatest synteny (Fig. 1a), in agreement with a recent report in which joining of S. cryophilus supercontigs20 into chromosome arm-sized assemblies and comparative analysis identified translocations and inversion events that occurred during divergence of fission yeast species22. Synteny is preserved adjacent to centromeres (Fig. 1b). Circos plots indicate a chromosome arm translocation occurred within two ancestral centromeres to generate S. cryophilus cen2 (S.cry-cen2) and S.cry-cen3 relative to S. octosporus and S. pombe (Fig. 1b). Despite centromere-adjacent synteny, Schizosaccharomyces centromeres lack detectable sequence homology (see below). All centromeres contain a central domain: central core (cnt) surrounded by inverted repeat (imr) elements unique to each centromere (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 1,2, Supplementary Data 3,4). CENP-ACnp1 localizes to fission yeast centromeres (Fig. 2a) and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) indicates that central domains are assembled in CENP-ACnp1 chromatin, flanked by various outer-repeat elements assembled in H3K9me2 heterochromatin (Fig. 2b, c). Despite the lack of sequence conservation, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromere organization is strongly conserved with that of S. pombe, having CENP-ACnp1-assembled central domains separated by clusters of tRNA genes from outer repeats assembled in heterochromatin13,14 (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Data 5). In contrast, our analyses of partially assembled, transposon-rich centromeres of Schizosaccharomyces japonicus reveals the presence of heterochromatin on all classes of retrotransposons and CENP-ACnp1 on only two classes (Tj6 and Tj7; Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 4)20.

Genome organization and synteny in Schizosaccharomyces. a Circos plots depicting pairwise S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus genome synteny. Rings from outside to inside represent the following: chromosomes; GC content (high: red, low: yellow); 5S rDNAs (red); tRNA genes (black); LTRs (green); CENP-ACnp1 ChIP-seq (purple); H3K9me2 ChIP-seq (orange); innermost ring and coloured connectors indicate regions of synteny between species. S. pombe chromosomes are indicated by blue (S.pom-chr1), green (S.pom-chr2), red (S.pom-chr3) in the left and right panels, and regions of synteny on S. octosporus and S. cryophilus chromosomes, respectively, are indicated in corresponding colours. A similar designation is used for S. octosporus chromosomes in the middle panel. b Circos plot isolating regions adjacent to centromeres highlighting preserved synteny and an intra-centromeric chromosome arm swap involving S. cryophilus cen2 and cen3 relative to S. pombe and S. octosporus. Source data available: GEO: GSE112454

Domain organization of Schizosaccharomyces centromeres. a Immunostaining of centromeres in indicated Schizosaccharomyces species with anti-CENP-ACnp1 antibody (green) and DNA staining (DAPI; red). Scale bar, 5 μm. b S. cryophilus centromere organization indicating DNA repeat elements. ChIP-seq profiles for CENP-ACnp1 (purple) and H3K9me2-heterochromatin (orange) are shown above each centromere. Positions of tRNA genes (single-letter code of cognate amino acid; black), 5S rDNAs (red) and solo LTRs are indicated (pink). Central cores (cnt—purples) innermost repeats (imr—blue shades). 5S-associated repeats (cFSARs—orange shades); tRNA gene-associated repeats (TARs) containing clusters of tRNA genes (green shades); heterochromatic repeats (cHR) and TARs associated with single tRNA genes (various colours: brown/pink/red). cTAR-14s, containing retrotransposon remnants (deep pink). For details, including individual repeat annotation, see Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 3,4. c S. octosporus centromere organization indicating DNA repeat elements. Labelling and shading as in b. Only oTAR-14ex (pale pink part) contain retrotransposon remnants. Colouring is indicative of homology within each species but only of possible repeat equivalence (not homology) between species; see Supplementary Table 5,6,19. Source data available: GEO: GSE112454 and in Source Data file

Syntenic clusters of tRNA genes at centromeres

Numerous 5S rRNA genes (5S rDNAs) are located in the heterochromatic outer repeats of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres (but not S. pombe) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Data 6, 7). Almost all (25/26; 20/20) are within Five-S-Associated Repeats (FSARs; 0.6–4.2 kb) (Fig. 3a), encompassing ~35% of outer-repeat regions. FSARs exhibit 90% intra-class homology (Supplementary Table 5) but no interspecies homology. The three types of FSAR repeats almost always occur together, in the same order and orientation, but vary in copy number: S. octosporus: (oFSAR-1)1(oFSAR-2)1–9(oFSAR-3)1; S. cryophilus: (cFSAR-1)1-3(cFSAR-2)1-2(cFSAR-3)1. Both sides of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres contain at least one FSAR-1-2-3 array, except the right side of S.cry-cen2 with two lone cFSAR-3 elements (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4). S. cryophilus cFSAR-2 and cFSAR-3 repeats share ~400 bp homology (88% identity), constituting hsp16 heat-shock protein open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Data 8) that are intact, implying functionality, selection and expression in some situations. Phylogenetic gene trees indicate that cFSAR-3-hsp16 genes are more closely related with each other than with those in subtelomeric regions or cFSAR-2s (Fig. 3b), consistent with repeat homogenization23,24,25. cFSAR-1s contain an eroded ORF with homology to a small hypothetical protein and S. octosporus oFSAR-2s contain a region of homology with a family of membrane proteins (Fig. 3a). The functions of centromere-associated hsp16 genes and other ORF-homologous regions remain to be explored.

S. cryophilus and S. octosporus contain conserved clusters of tRNA genes and similar nonhomologous repeat elements. a Schematic of S. cryophilus and S. octosporus FSAR repeats, indicating positions of 5S rDNAs, hsp16 genes and other ORFs. Copy number of each FSAR within centromeric arrays is indicated. b Phylogenetic relationship of S. cryophilus centromeric hsp16 genes with genomic hsp16 and hsp20 genes of S. cryophilus, S. octosporus, S. pombe and S. japonicas. c Heat map of tRNA gene frequency at centromeric and non-centromeric sites (blue shades) for S. pombe, S. cryophilus and S. octosporus. Anticodons and cognate amino acids indicated right (purple: present at centromeres). Clusters containing these tRNA genes indicated. Histogram (top): total tRNA gene frequencies in centromeres and non-centromeric sites of indicated species. Histogram (left): tRNA gene frequencies in each species. d Depiction of centromeric tRNA gene clusters and subclusters. Combinations of 2 or 3 tRNA genes subclusters present in both species (purple) or specific to S. octosporus (red) or S. cryophilus (blue) are indicated (single-letter code of cognate amino acid; arrows indicate plus or minus strand). e Top: Dot-plot alignment (MEGABLAST) showing synteny between oTAR-4/oTAR-5 (DVAIR-Cluster 1) from S.oct-cen1R (chr1:3355194-3357165) with oTAR-4/oTAR-5 (DVAIR-Cluster 1) from S.cry-cen3R (chr3:964707-966623). Bottom: Dot-plot of oTAR-4/oTAR-5 (DVAIR-Cluster 1) from S.oct-cen1R (chr1:3355194-3357165) and oTAR-4/oTAR-5 (DVAIR-Cluster 1) from S.oct-cen3L (chr3:1791072-1793051). f Schematic of central domain similarity between species. Central cores (purple shades), imr (blues), TARs containing tRNA gene clusters (greens). Long (CNT-L) and short (CNT-S) central-core repeats are indicated. tRNA genes indicated in single-letter amino acid code. Colours highlight similarity of organization between species and indicates homology within, not between, species. Source data available: GEO: GSE112454

S. cryophilus heterochromatic outer repeats contain additional repetitive elements, including a 6.2 kb element (cTAR-14) with homology to the retrotransposon Tcry1 and transposon remnants at the mating-type locus20 (Figs. 1a, 2b, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 1,6 and Supplementary Data 3). Tcry1 is located in the chrIII-R subtelomeric region (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Data 1). Although no retrotransposons have been identified in S. octosporus, remnants are present in the mating-type locus and oTAR-14ex in S.oct-cen3 outer repeats (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Figs. 1, 4, Supplementary Tables 2, 7 and Supplementary Data 4). Hence, transposon remnants, FSARs and other repeats are assembled in heterochromatin at S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres, and potentially mediate heterochromatin nucleation.

tRNA gene clusters occur at transitions between CENP-A and heterochromatin domains in two of three centromeres in S. octosporus (S.oct-cen2, S.oct-cen3) and S. cryophilus (S.cry-cen1, S.cry-cen2), and are associated with low levels of both H3K9me2 and CENP-ACnp1 (Fig. 2b, c), suggesting that they may act as boundaries, as in S. pombe26,27,28. No tRNA genes demarcate the CENP-A/heterochromatin transition at S.cry-cen3. Instead, this transition coincides precisely with 270 bp LTRs (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Tables 1, 6 and Supplementary Data 3), which may also act as boundaries29,30,31. Similar to tRNA genes, LTRs have been shown to be regions of low nucleosome occupancy, which may counter spreading of heterochromatin31,32. The transition between CENP-ACnp1 and heterochromatin is poorly demarcated at S.oct-cen1 compared with other centromeres. This region lacks tRNA genes and, as only retrotransposon remnants are detectable in S. octosporus, the sequence of putative LTRs is unknown. It is possible that the long inverted imr repeats comprise a gradual transition zone at this centromere. tRNA gene clusters also occur near the extremities of all centromeres in both species, separating heterochromatin from adjacent euchromatin. tRNA genes and LTRs are thus likely to act as chromatin boundaries at fission yeast centromeres.

A high proportion (~32%) of tRNA genes in S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus genomes are located within centromere regions33 (Figs. 1a, 3c, Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Data 9, 10). Centromeric tRNA genes are intact and are conserved in sequence with their genome-wide counterparts, indicating that they are functional genes. Two major, conserved tRNA gene clusters reside exclusively within S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres (p-value < 0.00001; q-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3c, d). Cluster 1 comprises several subclusters of 2–3 tRNA genes in various combinations of up to 8 tRNA genes, whereas Cluster2 contains up to 5 tRNA genes (Fig. 3d); 17 different tRNA genes (14 amino acids) are represented, none of which are unique to centromeres (Fig. 3c). Intriguingly, the order and orientation of tRNA genes within clusters is conserved between species, but intervening sequence is not (Fig. 3d, e). Strikingly, as well as local tRNA gene cluster conservation, inspection of centromere maps reveals synteny of tRNA genes and clusters across large portions of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres. For example, the tRNA gene order AIR-RKL-E-T-T-L-DVAIR-RKLEF-A-DV (single-letter code) is observed at S.oct-cen1 and S.cry-cen3 (Supplementary Fig. 7). This synteny, together with both possessing small central cores and long imrs, suggests that these two centromeres are ancestrally related (Fig. 3f ). Similarly, at S.oct-cen3 and S.cry-cen2, tRNA genes occur in the order NME-DV-AIRKE-EKRIA-VD-EMN-RIAVD, and at S.oct-cen2 and S.cry-cen1 the same tRNA genes are present in the imr repeats and beyond (FELK-KL-E-DV). Central cores have similar sizes and structures in the two species, each containing long (oCNT-L(6.4 kb); cCNT-L(6.0 kb)) and short (oCNT-S(1.2 kb); cCNT-S(1.3 kb)) species-specific repeats (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 9 and Supplementary Data 3, 4). CNT repeats are arranged head-to-tail at one centromere and head-to-head at the other centromere in each species. Together, these similarities suggest ancestral relationships between S.oct-cen2 and S.cry-cen1, So-cen3 and Scry-cen2. Further, in places where synteny appears to break down, patterns of tRNA gene clusters suggest specific centromeric rearrangements occurred between the species. For instance, tRNA gene clusters at the edges of S.cry-cen2R and S.cry-cen3L are consistent with an inter-centromere arm translocation relative to S.oct-cen1R and S.oct-cen2R, indicated by gene synteny maps (Figs. 1b, 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7).

Schizosaccharomyces centromeres share ancestry and sequence features. a Structural alignment of putatively equivalent centromere repeat elements of S. cryophilus and S. octosporus to highlight potential centromere rearrangements during evolution. b Principal component analysis PC1 and PC2 of 5-mer frequencies of three fission yeast genomes. Genome regions (12 kb window) were assigned to one of five specific annotated groups (CENP-ACnp1-associated (purple, n = 24), centromeric heterochromatin (orange, n = 112), mating-type locus (blue, n = 18), subtelomeres (yellow, n = 67), neocentromere-forming regions34 (red, n = 9), or other genome regions (grey, n = 7652). For each group the oval line encloses 95% of the data points. c Boxplot principal component PC1 of each group. Colours and values for n as in b. Mean comparison between groups was used (p-value: > 0.05, ns; *p > 0.01; **p > 0.001; ***p > 0.0001; ****p < 0.0001)66. Centre line, medium; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range; points, outliers. Source data available: GEO: GSE112454

Fission yeast centromeres show interspecies functionality

No central-core sequence homology was revealed between species using BLASTN. To identify potential underlying centromere sequence features, k-mer frequencies (5-mers), normalized for centromeric AT-bias, were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA). CENP-ACnp1-associated regions of S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus genomes all group together, distinct from the majority of non-centromere sequences (p-value, 9.3 × 10−7) (Fig. 4b, c). Interestingly, S. pombe neocentromere-forming regions34 also cluster separately from other genomic regions, sharing sequence features with centromeres. Surprisingly, taking GC content into account, the S. japonicus genome as a whole shows no significant difference in 5-mer frequency compared with the other three fission yeast genomes. In contrast, S. japonicus CENP-ACnp1-associated 5-mer frequencies show significant differences from its own wider genome sequence and from centromere sequences of the other fission yeast species (Supplementary Fig. 6).

K-mer analysis and conserved centromeric organization prompted us to investigate cross-species functionality of protein and DNA components of Schizosaccharomyces centromeres. green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged CENP-ACnp1 protein from each species localized to S. pombe centromeres and complemented the cnp1-1 mutant35 (Fig. 5a–c), indicating that heterologous CENP-A proteins assemble and function at S. pombe centromeres, despite normally assembling on nonhomologous sequences in their respective organisms.

Cross-species functionality of CENP-ACnp1 proteins. a Alignment of Schizosaccharomyces CENP-ACnp1 proteins. Positions of alpha helices (yellow), N-terminal tail (green) and CENP-A-targeting domain (CATD; red) are indicated. b S. pombe temperature-sensitive cnp1-1 cells expressing plasmid-borne GFP-CENP-ACnp1 from the indicated species (Sp, S. pombe; So, S. octosporus; Sc, S. cryophilus; Sj, S. japonicus), or GFP alone, were spotted on phloxine B-containing plates and incubated for 2–5 days at the indicated temperatures. c Localization of GFP-tagged CENP-ACnp1 from indicated Schizosaccharomyces species in S. pombe. Wild-type S. pombe cells bearing plasmids described in a were grown at 32 °C before fixation and staining with anti-GFP (green), anti-Cdc11 (red, spindle-pole body) and DAPI (blue, DNA). Centromeres cluster at the spindle-pole body in S. pombe. Scale bar, 5 μm. Source data available as a Source Data file

Introduction of S. pombe central-core (S.pom-cnt) DNA on minichromosomes into S. pombe results in the establishment and maintenance of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin if S.pom-cnt is adjacent to heterochromatin, or if CENP-A is overexpressed6,17,18,36. S.oct-cnt regions (3.2–10 kb) or S.pom-cnt2 (positive control) were placed adjacent to S. pombe outer-repeat DNA in minichromosome constructs (Fig. 6a), which were transformed into S. pombe cells overexpressing S. pombe GFP-CENP-ACnp1 (hi-CENP-ACnp1)18. Acquisition of centromere function is indicated by minichromosome retention on non-selective indicator plates (white/pale pink colonies) and by the appearance of sectored colonies (Fig. 6b, c). The pHET-S.pom-cnt2 minichromosome containing S.pom-cnt2 established centromere function at high frequency immediately upon transformation in hi-CENP-ACnp1 cells (Table 1). Centromere function was also established on S.oct-cnt-containing minichromosomes in hi-CENP-ACnp1 cells (Fig. 6b, c and Table 1). CENP-ACnp1 ChIP-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) indicated that, for minichromosomes with established centromere function, CENP-ACnp1 chromatin was assembled on nonhomologous S.oct-cnt DNA, to levels similar to those at endogenous S. pombe centromeres and to S.pom-cnt2 on a minichromosome (Fig. 6d). Minichromosomes containing S.oct-cnt provided efficient segregation function (Table 1), no longer requiring CENP-ACnp1 overexpression to maintain that function once established (Fig. 6e), consistent with the self-propagating ability of CENP-A chromatin5,18. Minichromosomes containing S. cryophilus central-core regions (S.cry-cnt) were also able to establish functional centromeres and segregation function in S. pombe. These S.cry-cnt-bearing minichromosomes assembled CENP-ACnp1 chromatin to high levels, similar to those at endogenous S. pombe centromeres (Supplementary Fig. 8). Centromere function was not due to minichromosomes gaining portions of S. pombe central-core DNA (Supplementary Fig. 9). A similar minichromosome bearing a region (retrotransposon Tj7) highly enriched for CENP-ACnp1 in S. japonicus did not convincingly form functional centromeres when introduced into S. pombe or assemble CENP-ACnp1 chromatin to an appreciable extent (Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus centromeres share a similar organization, underlying sequence features and cross-species establishment of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin, whereas putative S. japonicus centromeres appear not to share these attributes. Our analyses indicate that S.oct-cnt and S.cry-cnt DNAs are competent to establish CENP-A chromatin and centromere function in S. pombe when CENP-ACnp1 is overexpressed, suggesting that S. octosporus and S. cryophilus central-core DNA have intrinsic properties that promote the establishment of CENP-A chromatin despite lacking sequence homology.

S. octosporus central-core DNA establishes CENP-ACnp1 chromatin upon introduction into S. pombe. a Indicated regions of S. octosporus central-core DNA placed adjacent to a portion of S. pombe heterochromatin-forming outer-repeat sequence on a plasmid. b S. pombe transformants containing minichromsome plasmids were replica-plated to low-adenine non-selective plates: colonies retaining the chimeric minichromosome plasmid are white/pale pink, those that lose it are red. Representative plate showing pKp-So-cnt3-6.5kb-containing colonies. c S. pombe cells containing pKp-So-cnt3-6.5 kb chimeric minichromosome were streaked to single colonies. Red colour indicates loss of minichromosome; small red sectors indicate low-frequency minichromosome loss and mitotic segregation function. d ChIP-qPCR for CENP-ACnp1 on S. pombe hi-CENP-ACnp1 cells containing chimeric minichromosomes with established centromere function. Three biologically independent transformants were analysed for each minichromosome (n = 3). ChIP enrichment on S.pom-cnt2 and S.oct-cnt-bearing minichromosomes is normalized to the level at endogenous S. pombe cnt1. Individual data points are shown as black dots. Error bars, SD. e Propagation of chimeric minichromosome stability. Cells containing pK(5.6 kb)-So-cnt2-10 kb were streaked on low-adenine-containing plates with or without thiamine, which results in repression or expression of high levels of S. pombe CENP-ACnp1. Source data available as a Source Data file

Discussion

Our analyses indicate that the centromeres of S. pombe, S. octosporus and S. cryophilus share a conserved organization of a CENP-ACnp1-assembled central-core flanked by outer repeats assembled in H3K9me heterochromatin. Despite this conservation of organization, centromere sequence is not conserved, although underlying sequence features are detectable by PCA of 5-mer frequencies. The cross-species functionality of S.oct-cnt and S.cry-cnt central-core DNA in S. pombe suggests that the central-core regions of these three species are favoured substrates, sharing intrinsic properties that promote the establishment of CENP-ACnp1 chromatin, properties that S.jap-Tj7 may lack. Although the nature of putative conserved CENP-A-promoting properties is unknown, recent studies have revealed distinctive characteristics of centromeric DNA. S. pombe central-core DNA has the innate property of driving high rates of histone-H3 nucleosome turnover, causing low nucleosome occupancy19 and may programme pervasive low-quality RNAPII transcription to promote assembly of CENP-A chromatin18. These and other properties, such as non-B form DNA37, may contribute to an intrinsic CENP-A deposition programme conserved between Schizosaccharomyces centromeric DNA.

Based on conserved features, ancestral Schizosaccharomyces centromeres may have consisted of a CENP-ACnp1-assembled central-core surrounded by tRNA gene clusters and 5S rDNAs. We surmise that RNAPIII promoters perhaps provided targets for transposon integration38, followed by heterochromatin formation to silence retrotransposons and preserve genome integrity39,40. The ability of heterochromatin to recruit cohesin41,42, benefitting chromosome segregation, selected for heterochromatin maintenance43,44, rather than selecting for underlying sequence, which evolved by repeat expansion and continuous homogenization23,24,25. As tRNA genes may have performed important functions—as boundaries preventing heterochromatin spread into central cores and perhaps in higher-order centromere organization and architecture—tRNA gene clusters were maintained26. In S. pombe, non-centromeric and centromeric tRNA genes and 5S rDNAs cluster adjacent to centromeres in a TFIIIC-dependent manner27,28. The multiple tandem centromeric 5S rDNAs and tRNA genes could contribute to a robust, highly folded heterochromatin structure promoting optimum kinetochore configuration for co-ordinated microtubule attachments and accurate chromosome segregation44.

The lack of overt sequence conservation between centromeres of different species appears not to prevent functional conservation, which may be driven by underlying sequence features or properties such as the transcriptional landscape. Maintenance of centromere function has been observed at a pre-established human centromere (pre-assembled with CENP-A and an intact, functional kinetochore) in chicken cells45 (310 My divergence). Establishment of CENP-A chromatin on human alpha-satellite in mouse cells46 (90 My divergence) is dependent on the 17 bp CENP-B box present at both human (alpha-satellite) and mouse (minor satellite) centromere sequences, and on the CENP-B protein. This conserved functionality is surpassed by the competence of S. octosporus central-core DNA to establish CENP-A chromatin in S. pombe from which it is separated by 119 My of evolution20 (equivalent to 383 My using a chordate molecular clock) and lacks any clear conserved sequence elements akin to a CENP-B box. The analyses presented thus extend the evolutionary timescale over which cross-species establishment of CENP-A chromatin has been demonstrated.

Methods

Cell growth and manipulation

Standard genetic and molecular techniques were followed. Fission yeast methods were as described47. Strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 10. All Schizosaccharomyces strains were grown at 32 °C in YES (Yeast Extract with Supplements), except S. cryophilus, which was grown at 25 °C, unless otherwise stated. S. pombe cells carrying minichromosomes were grown in PMG-ade-ura. For low GFP-tagged CENP-ACnp1 protein expression from episomal plasmids, cells were grown in PMG-leu with thiamine.

PacBio sequencing of genomic DNA

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was prepared from S. cryophilus, S. octosporus and S. japonicus using a Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture DNA Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequencing was carried out at the CSHL Cancer Center Next Generation Genomics Shared Resource. Samples were prepared following the standard 20 kb PacBio protocol. Briefly, 10–20 μg of genomic material was sheared via g-tube (Covaris) to 20 kb. Samples were damage repaired via ExoVII (PacBio), damage-repair mix and end-repair mix using standard PacBio 20 kb protocol. Repaired DNA underwent blunt-end ligation to add SMRTbell adaptors. For some libraries, 10–50 kb molecules from 1 to 2 μg SMRTbell libraries were size selected using BluePippin (Sage Science), after which samples were annealed to Pacbio SMRTbell primers per the standard PacBio 20 kb protocol. Annealed samples were sequenced on the PacBio RSII instrument with P4/C3 chemistry. Magbead loading was used to load each sample at a concentration between 50 and 200 pM. Additional PacBio sequencing (without BluePippin) was performed by Biomedical Research Core Facilities, University of Michigan. There, the following kits were used: DNA Sequencing Kit XL 1.0, DNA Template Prep Kit 2.0 (3 kb–10 kb) and DNA/Polymerase Binding Kit P4. MagBead Standard Seq v2 sequencing was performed using 10,000 bp size bin with no Stage Start with a 2 h observation time on a PacBio RSII sequencer. A summary of PacBio sequencing performed is listed in Supplementary Table 11.

De novo whole genome assembly of PacBio sequence reads

PacBio reads were assembled using HGAP3 (The Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process version 3)48. Reads were first sorted by length and the top 30% used as seed reads by HGAP3. All remaining reads of at least 1 kb in length were used to polish the seed reads. These polished reads were used to de novo assemble the genomes and Quiver software used to generate consensus genome contigs. Comparisons to the ChIP-seq input data and Broad Institute Schizosaccharomyces reference genomes20 showed very high agreement with these datasets. The S. octosporus and S. cryophilus chromosomes were named according to their sequence lengths, the longest chromosome being labelled as chromosome I in each case.

De novo assembly of S. pombe genome using nanopore technology

Genomic DNA was extracted as described previously49. Briefly, cells were incubated with Zymolyase 20T to digest the cell wall, pelleted, resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl pH8, 1 mM EDTA) and lysed with SDS, followed by addition of potassium acetate and precipitation with isopropanol. After treatment with RNase A and proteinase K, two phenol chloroform extractions were performed. DNA was precipitated in the presence of sodium acetate and isopropanol, followed by centrifugation and washing of the pellet with 75% ethanol. After air drying, the pellet was resuspended in TE. DNA purity and concentration were assessed using a Nanodrop 2000 and the double-stranded high-sensitivity assay on a Qubit fluorometer, respectively. Genomic DNA was sequenced using the MinION nanopore sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Three sequencing libraries were generated using the one-dimensional (1D) ligation kit SQK-LSK108, the two-dimensional (2D) ligation kit SQK-NSK007 and the 1D Rapid sequencing kit SQK-RAD002, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Each library was sequenced on one MinION flow cell. Sequencing reads were base-called using Metrichor (1D and 2D ligation libraries) or Albacore (rapid sequencing library). The combined dataset incorporating reads from three flow cells was assembled using Canu v1.5. The assembly was computed using default Canu parameters and a genome size of 13.8 Mbp. QUAST v3.2 was used to evaluate the genome assembly.

Genome annotation and chromosome structure

Genes were annotated onto the genome both de novo, using BLAST and the sequences of known genes, and by using liftover (https://genome-store.ucsc.edu) to carry over the previous gene annotation information from the Broad institute reference genomes (ref). CrossMap50 was then used to lift the chain files over to the new, updated genome. The locations of tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan51,52. Dfam 2.053 was used to annotate repetitive DNA elements. MUMmer3.2354 was used to compare the genomes and annotate repeat elements and tandem repeat sequences, including those located in centromeric domain and telomere sequences. Centromeric repeat elements were manually identified using BLASTN and MEGABLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Each repeat element was named according to their sequence features (association with tRNA gene and rDNAs) and locations. The sequence of the wild-type (h90) S. pombe mating-type locus was obtained by manually merging nanopore and PacBio contigs using available data20 (Supplementary Fig. 10) and information at www.pombase.org/status/mating-type-region. Genome synteny alignment analysis was carried out using syMAP4255,56, based on orthologous genes among the three genomes.

ChIP-quantitative PCR analysis

For analysis of CENP-ACnp1 association with minichromosomes bearing S. octosporus central-core DNA, three independent transformants with established centromere function (indicated by ability to form sectored colonies) for each minichromosome were grown in PMG-ade-ura cultures and fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. ChIP was performed as previously described57. Briefly, 2.5 × 108 cells were lysed by bead beating (Biospec) in 300 μl Lysis Buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate). Lysates were sonicated (Bioruptor, Diagenode) for 20 min (30 s on/off, high setting), followed by centrifugation at 17,000 × g (2 × 10 min) to pellet cell debris. Lysates were precleared for 1 h with 25 μl of Protein-G agarose beads (Roche) and 10 μl precleared lysate retained as ‘input’ sample. Three hundred microlitres of lysate was incubated overnight with 10 μl sheep anti-CENP-ACnp1 serum and 25 μl Protein-G agarose beads. Beads were washed with Lysis Buffer, Lysis Buffer with 500 mM NaCl, WASH buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.25 M LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate,1 mM EDTA) and TE. DNA was recovered from input and IP samples using Chelex resin (BioRad). Ten microlitres of anti-CENP-ACnp1 sheep antiserum57 (raised to the N-terminal 19 amino acids of S. pombe CENP-ACnp1) and 25 μl Protein-G-Agarose beads were used per ChIP. qPCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 and reagents (Roche), and analysed using LightCycler 480 Software 1.5 (Roche). Primers used in qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 12. Mean %IP ChIP values for Sp-cnt or So-cnt on minichromsomes were normalized to %IP for endogenous S. pombe cnt1. Error bars represent SD.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing

A modified ChIP protocol was used. Briefly, pellets containing 7.5 × 108 cells were lysed by four 1 min pulses of bead beating in 500 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), with resting on ice in between. The insoluble chromatin fraction was pelleted by centrifugation at 6000 × g and washed with 1 ml lysis buffer before resuspension in 300 μl lysis buffer containing 0.2% SDS. Chromatin was sheared by sonication using a Bioruptor (Diagenode) for 30 min (30 s on/off, high setting). Nine hundred microlitres of lysis buffer (no SDS) was added and samples clarified by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 20 min and the supernatant used for ChIP. Six microlitres of anti-H3K9me2 mouse monoclonal mAb5.1.158 (kind gift from Takeshi Urano) or 30 μl sheep anti-CENP-ACnp1 antiserum57 were used, along with protein-G-dynabeads (ThermoFisher Scientific) or Protein-G agarose beads (Roche), respectively. (For neocentromere strains, cells were first treated with Zymolyase 100T (AMS Biotechnology), washed in sorbitol and permeablized. Chromatin was fragmented with incubation with micrococcal nuclease. Cell suspensions were adjusted to standard ChIP buffer conditions and extracted chromatin was processed as per standard ChIP.) Immunoprecipitated DNA was recovered using Qiagen PCR purification columns. ChIP-Seq libraries were prepared with 1–5 ng of ChIP or 10 ng of input DNA. DNA was end-repaired using NEB Quick blunting kit (E1201L). The blunt, phosphorylated ends were treated with Klenow-exo− (NEB, M0212S) and dATP. After ligation of NEXTflex adaptors (Bioo Scientific) DNA was PCR amplified with Illumina primers for 12–15 cycles and library fragments of ~300 bp (insert plus adaptor sequences) were selected using Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). The libraries were sequenced following Illumina HiSeq2000 work flow (or as indicated in Supplementary Table 11).

Defining fission yeast centromeres

CENP-ACnp1 and H3K9me2 ChIP-seq data were generated to identify centromere regions. ChIP-Seq reads with mapping qualities lower than 30, or read pairs that were over 500 nt or <100 nt apart, were discarded. ChIP-seq data were normalized with respect to input data. Paired-end ChIP-seq data (single-end for S. japonicus) was aligned to the updated genome sequences using Bowtie259. Samtools60, Deeptools61 and IGV62 were subsequently used to generate sequence data coverage files and to visualize the data. MACS263 was used to detect CENP-ACnp1 and heterochromatin-enriched regions of the genome.

Centromere tRNA gene cluster analysis

To test for the enrichment of tRNA gene clusters at centromere regions, a greedy search approach was used to identify potential clusters. All tRNA genes <1000 bp apart were grouped into clusters. To test for significant clustering of tRNA genes at the centromere, the locations of tRNA genes across the genome were shuffled 1000 times. For each cluster observed in the real genome, the proportion of permutations where the same cluster was observed at least as many times was calculated to provide estimates of significance. Following conversion of these p-values to q-values to account for multiple testing, the centromere tRNA gene clusters each exhibited a q-value <0.005.

Hsp16 gene tree analysis

hsp16 paralogs from S. octosporus and S. cryophilus genomes were predicted using BLASTP. The predicted protein sequences from hsp16 genes across all four fission yeasts were aligned together with those from Saccharomyces cerevisiae using Clustal Omega. BEAST (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Trees)64 and FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) was used to generate and view the hsp16 gene phylogenetic tree.

5-mer frequency PCA

The CENP-ACnp1-associated sequences in the S. pombe, S. cryophilus and S. octosporus genomes are all ~12 kb in length. Each genome was therefore split into 12 kb sliding windows with a 4.5 kb overlap. The frequencies of each 5-mer was calculated in each window using Jellyfish65. CENP-ACnp1-associated regions showed a general enrichment of AT base pairs relative to the genome as a whole. To normalize for GC content among the windows, all base pairs were randomized in each sequence window to generate 1000 artificial sequences with the same GC content. 5-mer frequencies were then recalculated for each of these 1000 artificial sequences and the true original 5-mer frequencies compared with these background frequencies by calculating a z-score. Consequently, these enrichment scores represent the k-mer enrichments in a given sequence normalized for GC content. Genome windows were split into six groups: CENP-ACnp1-associated sequences (CENP-ACnp1 peaks covering >6 kb of sequence); outer-repeat heterochromatin regions (more than half the window covered by H3K9me2 peaks adjacent to CENP-A domains); subtelomeric regions (more than half the window covered by H3K9me peaks and close to the end of a chromosome); mating-type locus; neocentromere regions (identified using CENP-ACnp1 ChIP-seq data of S. pombe neocentromere-containing strains34); and remaining genome sequences. As the highly repetitive transposon-rich S. japonicus centromere regions are not fully assembled, the precise location of the centromere-kinetochore is unknown. We therefore adopted a limited PCA approach and selected the top 11 most highly enriched 12 kb regions from CENP-ACnp1 ChIP-seq (Supplementary Data 11). These were compared with ten randomly selected non-centromeric sequences from each of the fission yeast genomes as above.

Logistic regression and mean comparison were used to determine whether principal components were linked to the probability of a sequence belonging to a particular sequence group66. Logistic regression and mean comparison were used to determine whether principal components (FactoMineR) were linked to the probability of a sequence belonging to a particular sequence group.

Construction of minichromosomes

S. pombe functional minichromosomes contain central domain DNA and flanking repeat DNA on one side; the long, inverted repeats found in the natural context are not tolerated by Escherichia coli67. Regions of S. octosporus and S. cryophilus central-core regions were amplified with primers indicated in Supplementary Table 12 and inserted as BglII-NcoI, BamHI-NcoI or BglII-SalI fragments into BglII-NcoI- or BglII-SalI-digested plasmid pK(5.6 kb)-MCS-ΔBam, which contains a 5.6 kb fragment of the S. pombe K (dg) outer repeat. To create plasmid pK-So-cnt2-10 kb, an additional 3.6 kb region from S.oct-cnt2 was inserted as a BamHI-SalI fragment into BglII-SalI-digested pK-So-cnt2-6.5 kb to make a 10 kb region of S. octosporus central core. For pKp plasmids, S. octosporus or S. cryophilus central-core regions were by inserted as BglII-NcoI, SalI-BamHI or XhoI-BamHI fragments into BamHI-NcoI- or SalI-BamHI-digested plasmid pKp (pMC91), which contains 2 kb region from S. pombe K(dg) outer repeat. For the S. japonicus CENP-ACnp1-associated retrotransposon Tj720 (Supplementary Fig. 6), a region spanning the almost the entire retrotransposon (but lacking the second LTR to avoid rearrangement or transposition problems in E. coli or S. pombe) was amplified by PCR with primers indicated in Supplementary Table 12 and cloned in two steps into the NotI-XbaI site of pK(5.6 kb)-MCS-ΔBam to make pK-Sj-Tj7-4.8 kb. Plasmids are listed in Supplementary Table 13.

Centromere establishment assay

Strains A7373 or A7408, which contains integrated nmt41-GFP-CENP-ACnp1 to allow high level expression of CENP-A18, were grown in PMG-complete medium and transformed using sorbitol-electroporation method68. Cells were plated on PMG-uracil-adenine plates and incubated at 32 °C for 5–10 days until medium-sized colonies had grown. Colonies were replica-plated to PMG-low-adenine (10 μg/ml) plates to determine the frequency of establishment of centromere function. These indicator plates allow minichromosome loss (red) or retention (white/pale pink) to be determined. Minichromosome retention indicates that centromere function has been established, and that minichromosomes segregate efficiently in mitosis. In the absence of centromere establishment, minichromosomes behave as episomes that are rapidly lost. Minichromosomes occasionally integrate giving a false positive white phenotype. To assess the frequency of such integration events and to confirm establishment of centromere segregation function, a proportion of colonies giving the white/pale pink phenotype upon replica plating were re-streaked to single colonies on low-adenine plates—sectored colonies are indicative of segregation function with low levels of minichromosome loss, whereas pure white colonies are indicative of integration into endogenous chromosomes—and the establishment frequency adjusted accordingly.

Minichromosome stability assay

Minichromosome loss frequency was determined by half-sector assay. Briefly, transformants containing minichromsomes with established centromere function were grown in PMG-ade-ura to select for cells containing the minichromosome. At least two transformants were analysed per minichromosome. Cells were plated on low-adenine-containing plates and allowed to grow non-selectively for 4–7 days. Minichromosome loss is indicated by red sectors and retention by white sectors. To determine loss rate per division, all colonies were examined with a dissecting microscope. All colonies—except pure reds—were counted to give total number of colonies. Pure reds were checked for the absence of white sectors and were excluded, because they had lost the minichromosome before plating. To determine colonies that lost the minichromosome in the first division after plating, ‘half-sectored’ colonies were counted. This included any colony that was 50% or greater red (including those with only a tiny white sector). Loss rate per division is calculated as the number of half-sectored colonies as a percentage of all (non-pure-red) colonies.

Recovery of minichromosomes from S. pombe

To confirm that establishment of centromere function by minichromosome plasmids was not due to rearrangement or gain of S. pombe central-core sequences, minichromosomes were recovered from S. pombe into E. coli. Approximately 1 × 108 S. pombe cells containing minichromosome plasmids with established centromere function were incubated 1 ml PEMS buffer (100 mM PIPES pH 7, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.2 M Sorbitol) containing 1 mg/ml Zymolyase-100T (AMS Biotechnology) for 30–60 min at 36 °C to digest cell walls. After pelleting and washing with PEMS, spheroplasts were lysed and plasmid DNA isolated using Qiagen miniprep kit, following manufacturer’s instructions. Due to low-yield plasmids were recovered by transformation into E. coli gt116 cells, followed by restriction enzyme analysis of resultant miniprep DNA. Digestion patterns of recovered and original minichromsome plasmids was compared by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunolocalization

For localization of CENP-ACnp1, Schizosaccharomyces cultures were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 7 min, before processing for immunofluorescence as described57. Briefly, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 7 min, followed by cell-wall digestion with Zymolyase-100T (AMS Biotechnology) in PEMS buffer (100 mM PIPES pH 7, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.2 M Sorbitol). After permeablization with Triton X-100, cells were washed, blocked in PEMBAL (PEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% sodium azide, 100 mM lysine hydrochloride). Anti-CENP-ACnp1 sheep antiserum57 (raised to the N-terminal 19 amino acids of S. pombe CENP-ACnp1) was used in PEMBAL at 1:1000 dilution and Alexa-488-coupled donkey anti-sheep secondary antibody (A11015; Invitrogen) at 1:1000 dilution. Cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted in Vectashield. Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Imaging 2 microscope (Zeiss) using a × 100 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromat objective, Prior filter wheel, illumination by HBO100 mercury bulb. Image acquisition with a Photometrics Prime sCMOS camera (Photometrics, https://www.photometrics.com) was controlled using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging Corporation). Exposures were 1500 ms for FITC/Alexa-488 channel and 300–1000 ms for DAPI. Images shown in Fig. 2a are autoscaled.

To express GFP-tagged versions of Schizosaccharomyces CENP-ACnp1 proteins in S. pombe, ORFs were amplified from relevant genomic DNA using primers listed in Supplementary Table 12. Fragments were digested with NdeI-BamHI or NdeI-BglII and ligated into NdeI-BamHI digested pREP41X-GFP vector69 (Supplementary Table 13). For detection of GFP-tagged versions of Schizosaccharomyces CENP-ACnp1 proteins in S. pombe, cells containing pREP41X-GFP-CENP-ACnp1 episomal plasmids (variable copy number) were grown in PMG-leu + thiamine to allow low GFP-CENP-ACnp1 expression. Cells were fixed, processed for immunolocalization and microscopy as above. Anti-GFP antibody (A11122; Invitrogen) was used at 1:300 and anti-Cdc1157 (a spindle-pole body marker; gift from Ken Sawin) was used at 1:600. Secondary antibodies were, respectively, Alexa-488-coupled chicken anti-rabbit (A21441; Invitrogen) and Alexa-594-coupled donkey anti-sheep (A11016; Invitrogen), both at 1:1000. Exposures were FITC/488 channel 1500 ms, TRITC/594 1000 ms and DAPI 500–1000 ms. For display of images in Fig. 5C, TRITC/594 and FITC/488 images are scaled relative to the maximum intensity in the set of images, whereas DAPI images are autoscaled.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequence data generated in this study have been submitted to GEO under accession number: GSE112454. This study used PacBio and nanopore sequencing data under project PRJNA472404. Assembled genomes are available at http://bifx-core.bio.ed.ac.uk/~ptong/genome_assembly/. All other relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 2, 5, 6 and Supplementary Figs 6, 8, 9, are provided in a Source Data file. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file.

References

Buscaino, A., Allshire, R. & Pidoux, A. Building centromeres: home sweet home or a nomadic existence? Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 20, 118–126 (2010).

Plohl, M., Mestrović, N. & Mravinac, B. Centromere identity from the DNA point of view. Chromosoma 123, 313–325 (2014).

Malik, H. S. & Henikoff, S. Major evolutionary transitions in centromere complexity. Cell 138, 1067–1082 (2009).

Dumont, M. & Fachinetti, D. DNA sequences in centromere formation and function. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 56, 305–336 (2017).

Mendiburo, M. J., Padeken, J., Fülöp, S., Schepers, A. & Heun, P. Drosophila CENH3 is sufficient for centromere formation. Science 334, 686–690 (2011).

Folco, H. D., Pidoux, A. L., Urano, T. & Allshire, R. C. Heterochromatin and RNAi are required to establish CENP-A chromatin at centromeres. Science 319, 94–97 (2008).

Gómez-Rodríguez, M. & Jansen, L. E. Basic properties of epigenetic systems: lessons from the centromere. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 23, 219–227 (2013).

McKinley, K. L. & Cheeseman, I. M. The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 16–29 (2015).

Karpen, G. H. & Allshire, R. C. The case for epigenetic effects on centromere identity and function. Trends Genet 13, 489–496 (1997).

Scott, K. C. & Sullivan, B. A. Neocentromeres: a place for everything and everything in its place. Trends Genet. 30, 66–74 (2014).

Stimpson, K. M., Matheny, J. E. & Sullivan, B. A. Dicentric chromosomes: unique models to study centromere function and inactivation. Chromosome Res. 20, 595–605 (2012).

Barnhart, M. C. et al. HJURP is a CENP-A chromatin assembly factor sufficient to form a functional de novo kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 194, 229–243 (2011).

Partridge, J. F., Borgstrøm, B. & Allshire, R. C. Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 14, 783–791 (2000).

Allshire, R. C. & Ekwall, K. Epigenetic regulation of chromatin states in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a018770 (2015).

Martienssen, R. & Moazed, D. RNAi and heterochromatin assembly. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a019323 (2015).

Reyes-Turcu, F. E. & Grewal, S. I. Different means, same end-heterochromatin formation by RNAi and RNAi-independent RNA processing factors in fission yeast. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 22, 156–163 (2012).

Kagansky, A. et al. Synthetic heterochromatin bypasses RNAi and centromeric repeats to establish functional centromeres. Science 324, 1716–1719 (2009).

Catania, S., Pidoux, A. L. & Allshire, R. C. Sequence features and transcriptional stalling within centromere DNA promote establishment of CENP-A chromatin. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004986 (2015).

Shukla, M. et al. Centromere DNA destabilizes H3 nucleosomes to promote CENP-A deposition during the cell cycle. Curr. Biol. 28, 3924–3936.e4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.10.049

Rhind, N. et al. Comparative functional genomics of the fission yeasts. Science 332, 930–936 (2011).

Helston, R. M., Box, J. A., Tang, W. & Baumann, P. Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus sp. nov., a new species of fission yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 779–786 (2010).

Ács-Szabó, L., Papp, L.A., Antunovics, Z., Sipiczki, M., & Miklós I. Assembly of Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus chromosomes and their comparative genomic analyses revealed principles of genome evolution of the haploid fission yeasts. Sci. Rep. 8, 14629 (2018).

Dawe, R. K. & Henikoff, S. Centromeres put epigenetics in the driver’s seat. Trends Biochem Sci. 31, 662–669 (2006).

Roizès, G. Human centromeric alphoid domains are periodically homogenized so that they vary substantially between homologues. Mechanism and implications for centromere functioning. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1912–1924 (2006).

Sharma, A., Wolfgruber, T. K. & Presting, G. G. Tandem repeats derived from centromeric retrotransposons. BMC Genomics 14, 142 (2013).

Scott, K. C., Merrett, S. L. & Willard, H. F. A heterochromatin barrier partitions the fission yeast centromere into discrete chromatin domains. Curr. Biol. 16, 119–129 (2006).

Noma, K.-I., Cam, H. P., Maraia, R. J. & Grewal, S. I. S. A role for TFIIIC transcription factor complex in genome organization. Cell 125, 859–872 (2006).

Mizuguchi, T., Barrowman, J. & Grewal, S. I. S. Chromosome domain architecture and dynamic organization of the fission yeast genome. FEBS Lett. 589, 2975–2986 (2015).

Donze, D., Adams, C. R., Rine, J. & Kamakaka, R. T. The boundaries of the silenced HMR domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 13, 698–708 (1999).

Carabana, J., Watanabe, A., Hao, B. & Krangel, M. S. A barrier-type insulator forms a boundary between active and inactive chromatin at the murine TCRβ locus. J. Immunol. 186, 3556–3562 (2011).

Valenzuela, L. & Kamakaka, R. T. Chromatin insulators. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40, 107–138 (2006).

Steglich, B. et al. The Fun30 chromatin remodeler Fft3 controls nuclear organization and chromatin structure of insulators and subtelomeres in fission yeast. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005101 (2015).

Iben, J. R. & Maraia, R. J. tRNAomics: tRNA gene copy number variation and codon use provide bioinformatic evidence of a new anticodon:codon wobble pair in a eukaryote. RNA 18, 1358–1372 (2012).

Ishii, K. et al. Heterochromatin integrity affects chromosome reorganization after centromere dysfunction. Science 321, 1088–1091 (2008).

Takahashi, K., Chen, E. S. & Yanagida, M. Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288, 2215–2219 (2000).

Baum, M., Ngan, V. K. & Clarke, L. The centromeric K-type repeat and the central core are together sufficient to establish a functional Schizosaccharomyces pombe centromere. Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 747–761 (1994).

Kasinathan, S. & Henikoff, S. Non-B-form DNA is enriched at centromeres. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 949–962 (2018).

Guo, Y., Singh, P. K. & Levin, H. L. A long terminal repeat retrotransposon of Schizosaccharomyces japonicus integrates upstream of RNA pol III transcribed genes. Mob. DNA 6, 19 (2015).

Plohl, M., Luchetti, A., Mestrović, N. & Mantovani, B. Satellite DNAs between selfishness and functionality: structure, genomics and evolution of tandem repeats in centromeric (hetero)chromatin. Gene 409, 72–82 (2008).

Nishibuchi, G. & Déjardin, J. The molecular basis of the organization of repetitive DNA-containing constitutive heterochromatin in mammals. Chromosome Res. 25, 77–87 (2017).

Nonaka, N. et al. Recruitment of cohesin to heterochromatic regions by Swi6/HP1 in fission yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 89–93 (2002).

Bernard, P. et al. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294, 2539–2542 (2001).

Peters, J.-M. & Nishiyama, T. Sister chromatid cohesion. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011130–a011130 (2012).

Gregan, J. et al. The kinetochore proteins Pcs1 and Mde4 and heterochromatin are required to prevent merotelic orientation. Curr. Biol. 17, 1190–1200 (2007).

Shen, M. H., Yang, J. W., Yang, J., Pendon, C. & Brown, W. R. The accuracy of segregation of human mini-chromosomes varies in different vertebrate cell lines, correlates with the extent of centromere formation and provides evidence for a trans-acting centromere maintenance activity. Chromosoma 109, 524–535 (2001).

Okada, T. et al. CENP-B controls centromere formation depending on the chromatin context. Cell 131, 1287–1300 (2007).

Moreno, S., Klar, A. & Nurse, P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Meth. Enzym. 194, 795–823 (1991).

Chin, C.-S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569 (2013).

Murray, J. M., Watson, A. T. & Carr, A. M. Molecular genetic tools and techniques in fission yeast. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, pdb.top087601 (2016).

Zhao, H. et al. CrossMap: a versatile tool for coordinate conversion between genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 30, 1006–1007 (2014).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–W689 (2005).

Hubley, R. et al. The Dfam database of repetitive DNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D81–D89 (2016).

Kurtz, S. et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5, R12 (2004).

Soderlund, C., Nelson, W., Shoemaker, A. & Paterson, A. SyMAP: A system for discovering and viewing syntenic regions of FPC maps. Genome Res. 16, 1159–1168 (2006).

Soderlund, C., Bomhoff, M. & Nelson, W. M. SyMAP v3.4: a turnkey synteny system with application to plant genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e68–e68 (2011).

Castillo, A. G. et al. Plasticity of fission yeast CENP-A chromatin driven by relative levels of histone H3 and H4. PLoS Genet. 3, e121 (2007).

Nakagawachi, T. et al. Silencing effect of CpG island hypermethylation and histone modifications on O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene expression in human cancer. Oncogene 22, 8835–8844 (2003).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Ramírez, F., Dündar, F., Diehl, S., Grüning, B. A. & Manke, T. deepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W187–W191 (2014).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Drummond, A. J. & Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Kruskal, W. H. & Wallis, W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Joournal Am. Ctatistical Soc. 47, 583–621 (1952).

Hahnenberger, K. M., Carbon, J. & Clarke, L. Identification of DNA regions required for mitotic and meiotic functions within the centromere of Schizosaccharomyces pombe chromosome I. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 2206–2215 (1991).

Suga, M. & Hatakeyama, T. High efficiency transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe pretreated with thiol compounds by electroporation. Yeast 18, 1015–1021 (2001).

Craven, R. A. et al. Vectors for the expression of tagged proteins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 221, 59–68 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank Alastair Kerr, Shaun Webb and Daniel Robertson for bioinformatics support, David Kelly for microscopy support, Ken Sawin and Takeshi Urano for antibodies, and Kojiro Ishii, Ken Sawin and Nick Rhind for yeast strains. We thank Robert Lyons, Joe Washburn, Christina McHenry (University of Michigan) and Greg J. Hannon, Richard McCombie, Eric Antoniou and Sara Goodwin (CSHL) for PacBio sequencing. We are grateful to Chris Ponting for advice and comments on the manuscript and to Sandra Catania and other members of the Allshire and Heun labs for helpful discussions. N.R.T.T., R.A. and J.T.-G. were supported by the Darwin Trust of Edinburgh. The Darwin Trust and a Principal’s Career Development scholarship supported N.R.T.T. P.T. was partly supported by funding from the European Commission Network of Excellence EpiGeneSys- (HEALTH-F4-2010-257082) and a Wellcome Enhancement Award (095021) to R.C.A. R.C.A. is a Wellcome Principal Research Fellow (095021, 200885); the Wellcome Centre for Cell Biology is supported by core funding from Wellcome (203149). C.A.M. and C.A.N. are supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grant BB/N016858/1 and Wellcome Investigator Award 110064/Z/15/Z. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequencing carried out at the CSHL Cancer Center Next Generation Genomics Shared Resource, which is supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508 was paid for by a kind gift from Kathryn W. Davis to G.J.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C.A. and A.L.P. designed the study. P.T. performed the PacBio genome assemblies and bioinformatics, ChIP-seq analysis and PCA analysis. C.M. performed the nanopore sequencing of S. pombe supervised by C.N. H.B., N.R.T.T., J.T.-G. and R.A. generated ChIP-seq data with contribution from M.S. A.L.P. performed cytology, analysis of repetitive regions and experiments on cross-species functionality. R.C.A. supervised the study. A.L.P. wrote the manuscript with contributions from P.T., R.C.A. and other authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Fernando Azorin, Gernot Presting and other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, P., Pidoux, A.L., Toda, N.R.T. et al. Interspecies conservation of organisation and function between nonhomologous regional centromeres. Nat Commun 10, 2343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09824-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09824-4

This article is cited by

-

Proteasome-dependent truncation of the negative heterochromatin regulator Epe1 mediates antifungal resistance

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2022)

-

Epigenetic gene silencing by heterochromatin primes fungal resistance

Nature (2020)

-

Genetic and epigenetic effects on centromere establishment

Chromosoma (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.