Abstract

Crystalline solids are generally known as excellent heat conductors, amorphous materials or glasses as thermal insulators. It has thus come as a surprise that certain crystal structures defy this paradigm. A prominent example are type-I clathrates and other materials with guest-host structures. They sustain low-energy Einstein-like modes in their phonon spectra, but are also prone to various types of disorder and phonon-electron scattering and thus the mechanism responsible for their ultralow thermal conductivities has remained elusive. Our thermodynamic and transport measurements on various clathrate single crystal series and their comparison with ab initio simulations reveal an all phononic Kondo effect as origin. This insight devises design strategies to further suppress the thermal conductivity of clathrates and other related materials classes, with relevance for thermoelectric waste heat recovery and, more generally, phononic applications. It may also trigger theoretical work on strong correlation effects in phonon systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing world wide energy consumption and the associated climate change call for enhancing the overall energy efficiency of technological energy conversion processes. Thermoelectrics1,2,3,4,5,6 can convert waste heat into electricity and could thus contribute to such an efficiency increase. The perfect thermoelectric material combines low phonon thermal conductivity with high electrical conductivity and high thermopower. Materials classes with cage-like structures such as the clathrates7,8 or skutterudites4,9 show surprisingly low phonon thermal conductivities κph, even in perfect single crystals. Type-I clathrates G8H46, that show promising thermoelectric figures of merit5,10,11, consist of host atoms (H) that encapsulate guest atoms (G) in a framework of oversized cages (Fig. 1a). Recent inelastic neutron and X-ray scattering studies uncovered energetically low-lying optical phonon modes which were attributed to a so-called rattling motion of the guest atoms in the cages and are thus referred to as Einstein modes12,13,14. Similar observations were also made for skutterudites9 and clathrate hydrates15. A severe flattening of the acoustic phonon branches at energies near the optical modes was observed12,13,14, and attributed to a finite coupling between the guest atoms and the host cages. Early thermal conductivity studies on type-I clathrates16,17, inspired by investigations on glasses18, tried to capture this guest-host coupling by including terms for resonance scattering – originally proposed to describe the resonance interaction between phonons and non-paramagnetic defects19, and for scattering from tunneling states18 – into phenomenological treatments20. Whereas empirical multi-parameter fits including these terms can indeed model thermal conductivity data of several type-I clathrates below about 50 K (refs. 16,17), inconsistencies with other results have been pointed out more recently. Notably, such modeling can neither explain the exceptionally long phonon lifetimes12,21 nor the large thermal conductivity differences between structurally very similar n- and p-type versions of these materials22. The recent achievement of ab initio calculations of the thermal conductivity of a type-I clathrate, based on intrinsic phonon-phonon Umklapp scattering processes23, represents a major step forward. It showed that, unlike in the resonance scattering picture, the phonon lifetimes are reduced in a wide frequency range. Nevertheless, also DFT calculations can explain experimental thermal conductivity data only at low temperatures, but strongly undershoot them at high temperatures.

Clathrate crystal structure. a Type-I clathrate crystal structure G8H46. Per unit cell 8 guest atoms (G, red) are situated in two different cages (smaller dodecahedra X20 and larger tetrakaidecahedra X24) built by the host (H, blue) atoms. The different crystallographic sites are labeled. b Sketch of an X24 cage with the two soft rattling directions e1 and e2 within the easy plane parallel to the two hexagonal faces of the cage. Each soft direction is parallel to the longest secant of one of the two hexagons, both defined by the 6c site (black atoms) of the structure. Incoming acoustic phonons with the two different transverse polarizations eT1 and eT2 are sketched by the sinusoidal waves

Here we propose an alternative mechanism, a Kondo-like phonon-phonon interaction, that can explain the difference as the disentanglement of Kondo-coupled acoustic and rattling phonon modes above the phonon Kondo temperature. In general terms, the Kondo effect describes non-commutative scattering of an extended wave from a localized entity with internal degree of freedom. It has been studied in many different settings, including magnetic, orbital, charge, and local vibrational degrees of freedom (see Supplementary Note 8 for more details). However, to the best of our knowledge, it has never been studied in an all phononic context.

Results

Steps beyond the state-of-the-art

To demonstrate the all phononic Kondo effect, we had to go beyond the state-of-the-art in thermoelectric clathrates’ research in several respects. Firstly, to overcome the bottleneck of large uncertainties and systematic errors of standard thermal conductivity measurements at elevated temperatures, we developed a high-precision implementation (Fig. 2a and “Methods” section) of the 3ω technique24. A second key ingredient for our work are sample series of single crystals, which allow us to pin down the dominating instrinsic phonon scattering mechanisms by employing an empirical model20, modified to be in line with the most recent findings21,23 on the phonon band structure and phonon dynamics in type-I clathrates. Thirdly, we compare both the thermal conductivity data and thermodynamic data to ab initio lattice dynamics calculations, thereby providing compelling evidence for the phonon Kondo effect.

Thermal conductivity data of type-I clathrate single crystals. a Exemplary frequency scan in the 3ω setup. Rectangles show the in-phase, circles the out-of-phase contribution of the temperature oscillation ΔT. The expected linear-in-logarithmic-frequency dependence of the in-phase temperature oscillation of the heater/thermometer line, that is observed at intermediate frequencies (between the hatched areas), is measured with an extremely low noise level. The slope of this dependence (full line) is inversely proportional to the thermal conductivity κ of the studied material. b Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of all studied materials. The data points represent the phonon thermal conductivities κph, calculated by subtracting an electronic contribution κel (lines and identifier symbols, right axis) from the total measured κ. Each data point above 80 K is determined from the slope of an isothermal ΔT vs log f curve (straight line in a). All sample compositions are given in the Supplementary Table 1

Phonon thermal conductivities

We start by giving an overview of the phonon thermal conductivities κph of all type-I clathrate single crystals studied here (Fig. 2b). Although type-I clathrates are often referred to as model systems for the enigmatic phonon-glass electron-crystal concept1, the most prominent feature of κph(T) is a large crystal-like maximum. It is narrow and occurs at a surprisingly low temperature of only about 10 K. As will be further detailed below, this narrow low-temperature maximum is a strong indication for the phonon transport not being controlled by the natural energy scale kBΘD of the Debye temperature ΘD but by a much smaller energy scale kBΘE.

To visualize the effect of a reduced Debye temperature, we use a simple phenomenological lattice thermal conductivity model: A modified version of the standard Callaway model20, where we replaced the Debye temperature ΘD by a variable temperature ΘE (Supplementary Note 1). The left panel of Fig. 3b shows temperature dependences of normalized phonon thermal conductivities calculated within this model for a series of different characteristic energies kBΘE, keeping fixed scattering rates \(\tau _{\mathrm{D}}^{ - 1}\) for defect scattering, \(\tau _{\mathrm{B}}^{ - 1}\) for boundary scattering, and \(\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - 1}\) for phonon-electron scattering. Resonance scattering is of minor importance here (Supplementary Fig. 4). With decreasing ΘE the broad maximum sharpens and is shifted to lower temperatures. This is attributed to a strongly enhanced Umklapp scattering rate \(\tau _{\mathrm{U}}^{ - 1}\) (Supplementary Note 1) that results from successively limiting the energy range of the contributing acoustic phonons as ΘE decreases.

Comparison of spin and phonon Kondo effect. a Schematic dispersion relations for electrons in heavy electron systems (left) and phonons in an analogously defined “heavy” phonon system (right). The blue and red curves represent the non-interacting dispersive and localized entities, respectively, the violet curves the hybridized interacting states. As function of temperature, the system evolves from non-interacting well above the Kondo temperature to interacting well below it. For simplicity, phonon branches above ωE are neglected. This is justified in real clathrates by the presence of multiple Einstein modes, resulting in multiple anticrossings13, 14. The Debye model (blue line, right) assumes ω = vsq where vs is the sound velocity. The new dispersion relation (violet, right) is characterized by the group velocity vg = ∂ω/∂q. It equals the sound velocity only at low wave vectors and frequencies. b Temperature-dependent phonon thermal conductivity, normalized to its maximum, calculated using a modified Callaway model (Supplementary Note 1) for various Einstein temperatures ΘE (left) and corresponding data for the Ge-based type-I clathrate BCGG1.0 (Supplementary Table 1) and elemental Ge, electron irradiated and annealed at 77 K to similar defect densities64 (right). c Specific heat and thermal expansion phonon Kondo anomaly, obtained by subtracting the experimental from the theoretical specific heat and thermal expansion curves of Ba8Ga16Ge30 (left axis, see Supplementary Figs. 1b and 2b and Methods) and the corresponding entropy (right axis). d The inverse difference of calculated and experimental41 phonon thermal conductivities of Ba8Ga16Ge30 (Supplementary Fig. 3b), showing the −ln T hallmark (full red line) of incoherent Kondo scattering in the spin Kondo effect above the Kondo temperature (dashed vertical line). The error bars represent the error of ±3% specified for the thermal conductivity data41

This effect can be directly observed by experiments. The right panel of Fig. 3b compares the phonon thermal conductivities of a Ge-based type-I clathrate single crystal (BCGG1.0, see Supplementary Table 1) and single crystalline Ge, irradiated25 to a similar defect concentration. It is clear that the clathrate is governed by a strongly reduced energy scale. Both materials have similar Debye temperatures (Supplementary Note 2), but the clathrate has, in addition, a low-lying Einstein temperature ΘE, that apparently controls the behavior.

Dominating role of Umklapp scattering

Next, we prove, with two clathrate single crystal series, that the strong Umklapp scattering due to the new low-energy scale indeed dominates the lattice thermal conductivity in a wide temperature range. In the first such series, Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax (x = 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, y = 1.2 − x, see BCGGx in Supplementary Table 1), an increasing Ga content x is accompanied by a decreasing content y of host atom vacancies □. This is supported by the increase of the lattice parameter a (Fig. 4a) and the Hall mobility μH = RH/ρ = 1/(neρ) (combination of the two panels in Fig. 4c) with x, as well as by the charge neutrality of this substitution (both the electronic γ term of the specific heat and the charge carrier concentration n are essentially independent of x, see Fig. 4b, c bottom), as discussed in the Supplementary Note 3. Because the mass difference between Ga and Ge is very small, Ga represents a much weaker scattering potential26 in Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax than a vacancy. Thus, we expect a decrease of defect scattering with x. The low-temperature phonon thermal conductivity κph(T) of all samples in this series shows a maximum at low temperatures that is systematically enhanced at nearly constant temperature with increasing x (Fig. 4d left). This trend is indeed well reproduced by a decrease of the point-defect scattering rate \(\tau _{\mathrm{D}}^{ - 1}\) with x, as seen by the good agreement of simulation and data for this case (full and dashed lines in Fig. 4d left). A much less satisfying agreement is observed if the boundary scattering rate \(\tau _{\mathrm{B}}^{ - 1}\) is allowed to change with x instead (Fig. 4d right). The phonon-electron scattering rate \(\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - 1}\) can be assumed to be x independent because of the above discussed charge neutrality. Above about 50 K, however, the κph(T) data for different x merge (Fig. 4d left), indicating that scattering from point defects has become negligible. This can be rationalized by comparing the (Debye) phonon wavelength λ = 2πvs / ω, where vs is the sound velocity (related to β, Fig. 4b), with the size of the scattering center. A vacancy with the distortion surrounding it was estimated to have a diameter d ≈ 5 Å (ref. 27). Strong point-defect scattering of Rayleigh type, with an ω4 dependence, occurs only if λ is at least an order of magnitude larger than d, corresponding to phonon energies ħω of 2.5 meV (30 K) and below. At much larger energies (and temperatures), defect scattering should be weak and frequency independent28.

Scattering contributions in clathrate single crystal series. a Lattice parameter vs x for Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax (BCGGx, Supplementary Table 1) and comparison with the series Ba8Ga14+xGe32−x (BGG are polycrystals synthesized by us, BGG1 are single crystals 4 and 6 from ref. 65, and BGG2 is a single crystal from ref. 66), which was shifted downwards by 89.6 mÅ for better readability. For the linear fits see Supplementary Note 3. b Coefficients γ and β of linear fits Cp/T = γ + βT2 to the specific heat data, normalized to their respective value for x = 0, of Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax below 3.5 K (not shown) vs x. c Electrical resistivity (top) and charge carrier concentration (bottom), determined from the Hall coefficient in a one-band model, RH = 1/(ne), as function of temperature for all Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax samples. d Phonon thermal conductivity vs temperature for all Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax samples (symbols), together with fits with the modified Callaway model (Supplementary Note 1) to the x = 0 data (red full line) and simulations (dashed lines) using the parameters of the x = 0 fit except for the defect scattering rate \(\tau _{\mathrm{D}}^{ - 1}\) (left) and the boundary scattering rate \(\tau _{\mathrm{B}}^{ - 1}\) (right). The respective scattering rate was decreased to the indicated percentage in direction of the arrow. The speed of sound of each sample was determined from β, the Einstein temperature ΘE from bell-shaped contributions to Cp/T3 versus logT. e Phonon thermal conductivity vs temperature for two different Ba8Ga16−xGe30+x samples from the literature30, 31, with lines corresponding to our fit to the data from ref. 30 and a simulation using essentially the same parameters except for a strongly enhanced phonon-electron scattering rate \(\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - 1}\) for the data from ref. 31

The second sample series is the prototypical clathrate Ba8Ga16−xGe30+x that has been much investigated in the past. It is an ideal system to study the importance of phonon-electron scattering because it has a low and essentially constant amount of point defects (as seen from the above, shown in ref. 26, and explained and demonstrated in the Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Fig. 5, respectively, Ga does not act as strong point defect in Ge clathrates) but a charge carrier concentration that varies strongly with x (ref. 29).

Indeed, different Ba8Ga16−xGe30 + x single crystals reported in the literature30,31 show severely different κph(T) at low temperatures. Figure 4e replots two extreme cases. The red line is our low-temperature fit (T < ΘE/2) with the modified Callaway model discussed in Supplementary Note 1 to the data of ref. 30. It takes Umklapp scattering \(\left( {\tau _{\mathrm{U}}^{ - 1}} \right)\), defect scattering \(\left( {\tau _{\mathrm{D}}^{ - 1}} \right)\), boundary scattering \(\left( {\tau _{\mathrm{B}}^{ - 1}} \right)\), and phonon-electron scattering \(\left( {\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - {\mathrm{1}}}} \right)\) into account. The latter is calculated from the reported materials properties30 as discussed in Supplementary Note 1. Interestingly, the κph(T) data of a different Ba8Ga16−xGe30+x single crystal31 can be very well reproduced by strongly increasing \(\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - 1}\) and by only slightly adjusting \(\tau _{\mathrm{U}}^{ - 1}\) (dashed line in Fig. 4e). Above about 50 K, the differences in κph caused by a different \(\tau _{{\mathrm{ph}} - {\mathrm{el}}}^{ - 1}\) vanish. This observation is in line with the fact that phonon-electron scattering can only occur for phonons with a wave vector q smaller than twice the Fermi wave vector kF. For the crystal of ref. 30 we estimate this to hold below about 140 K (Supplementary Note 2). At higher temperatures phonon-electron scattering is unlikely to be relevant.

A suppression of large low-temperature differences in κph(T) at higher temperatures has also been seen in other type-I clathrate single crystal series32,33, but precise high-temperature data on these are not available to date.

Taking both our clathrate series together we have managed to rule out the influence of defect and phonon-electron scattering on κph(T) of various type-I clathrates above 50 K. In addition, boundary scattering cannot contribute significantly in single crystals at these temperatures. Thus, at elevated temperatures, κph is dominated by intrinsic phonon-phonon (Umklapp) scattering. This allows us to pin down its microscopic origin, as shown in what follows.

Universal scaling

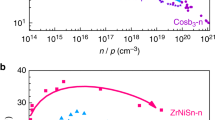

Remarkably, a broad range of clathrates, including even a gas hydrate15,34,35,36, shows a universal scaling of the room-temperature phonon thermal conductivity with the product of sound velocity and Einstein temperature of the lowest-lying rattling mode(s), κph ∝ vsΘE (Fig. 5). The simple kinetic gas relation \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}} = c_{\mathrm{v}}v_{\mathrm{s}}^2\tau {\mathrm{/}}3\) predicts κph to depend on the square of the sound velocity. In the Debye model the sound velocity is proportional to the Debye temperature and thus \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}} \propto v_{\mathrm{s}}^2 \propto \Theta _{\mathrm{D}}^2\) is expected for simple Debye solids. The modified scaling \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}} \propto v_{\mathrm{s}}{\mathrm{\Theta }}_{\mathrm{E}} \propto v_{\mathrm{s}}^2 \cdot \left( {{\mathrm{\Theta }}_{\mathrm{E}}{\mathrm{/\Theta }}_{\mathrm{D}}} \right)\) shows that the above discussed energy renormalization is universal in clathrates.

Universal scaling of the intrinsic phonon thermal conductivity of phonon Kondo compounds. Phonon thermal conductivities vs the product of sound velocity and lowest-lying Einstein temperature (Supplementary Note 5) for single crystalline intermetallic clathrates measured within this work (red circles), together with published data on intermetallic clathrates (grey circles), a Xe-filled ice hydrate (grey square), and the tetrahedrite Cu10.6Mn1.4Sb4S13 (CMSS, grey hexagon; see Supplementary Table 1 for all sample compositions and references). The open triangles are the minimum κph values derived using κmin of ref. 45. The open squares are the minimum κph values estimated as discussed in Supplementary Note 1

Analogy with spin Kondo effect

A similar energy renormalization is seen in heavy fermion metals, where the (spin) Kondo effect rescales the Fermi temperature TF to the (spin) Kondo temperature TK (refs. 37,38). Figure 3a illustrates this analogy with schematic dispersion relations for electrons and phonons. In a band picture for heavy electron systems (left) a broad conduction band (blue) hybridizes with a flat, essentially non-dispersing 4f band of (renormalized) energy \(\epsilon _{4f}\) (red). The hybridized bands (violet) are extremely flat near \(\epsilon _{4f}\), corresponding to quasiparticles with strongly renormalized effective masses. In the phonon case the strongly dispersing acoustic phonon mode, approximated here by the linear dispersion of the Debye model, takes the role of the broad conduction band, and the flat Einstein-like rattling mode at ħωE = kBΘE corresponds to the narrow 4f band. The resulting hybridized band is again extremely flat in large portions of the Brillouin zone, giving rise to “heavy” phonons with extremely low group velocity vg at finite wave vectors. Even though the resulting T = 0 dispersion relation may look similar to the one obtained from ab initio lattice dynamics simulations23, there is an important difference: Being a strong correlation phenomenon, the phonon Kondo effect has a characteristic temperature dependence. Well above the Kondo temperature, the interacting states (violet) go over to the non-interacting ones (red and blue), an effect referred to as crossover from infrared slavery to asymptotic freedom38, which is absent in the lattice dynamics simulations (see also “Discussion” section).

The fact that the observed universal scaling of κph still contains vs (to linear power) is attributed to the absence of a Fermi level in phonon systems. Whereas the electrical resistivity in heavy fermion metals is dominated by the heavy electrons at the Fermi wavevector kF, phonons of all wave vectors, including long-wavelength ones propagating with vs, contribute to κph.

Finally, we compare specific heat, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity data for the prototypical clathrate Ba8Ga16Ge30 with ab initio lattice dynamics calculations (see Methods) and reveal key characteristics of the Kondo effect. For the specific heat, the agreement between experiment and theory is excellent at low and high temperatures, but a distinct deviation is seen in between (Supplementary Fig. 1b). This difference gives rise to an anomaly near ΘE (Fig. 3c). It releases an entropy of order R ln2 per rattling atom at the 6d site. This is the behavior expected for any Kondo effect involving a 2-fold degenerate localized entity: Its degeneracy is lifted by the Kondo interaction, giving rise to the above entropy release. The entropy reaches 0.65 ln2 at 40 K. This temperature is considered as good estimate of the Kondo temperature39, which is thus found to be comparable to ΘE. The experimental thermal expansion is sizeably smaller than the theoretical prediction below 150 K, but agrees well with it above this temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The difference between the theoretical and experimental curve closely resembles the specific heat anomaly (Fig. 3c). These discrepancies in specific heat and thermal expansion translate into a corresponding discrepancy in the mode-averaged Grüneisen parameter: Ab initio calculations predict an upturn at low temperatures, an effect usually associated with enhanced phonon anharmonicity at low frequencies, that is however absent in the experimental curve (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Finally, the experimental phonon thermal conductivity is well described by the ab initio calculations below 50 K, but severely overshoots them at higher temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The difference, plotted as inverse to represent a thermal resistivity (Fig. 3d), increases with decreasing temperature, with a slow (about −ln T) dependence, the hallmark of incoherent Kondo scattering above TK in the original spin Kondo effect37,38.

Discussion

To understand these results, it is important to assess the limitations of the used ab initio calculations (see “Methods” section). The phonon density of states (DOS) and the specific heat are calculated in the harmonic approximation, the thermal expansion in the quasi-harmonic approximation, and the thermal conductivity from anharmonic interatomic force constants23. The latter thus takes phonon-phonon interactions to lowest order into account. However, temperature dependences resulting from strong phonon correlation effects, most notably the Kondo disentanglement of acoustic and rattling modes above the phonon Kondo temperature, cannot be captured by these simulations. This is why the comparison of experimental data and such calculations can be used to extract the characteristic temperature dependences due to the correlations (somewhat like non-f reference materials are used as background to reveal Kondo physics in heavy electron compounds – unfortunately, empty type-I clathrates without the rattling atoms, that would represent such background here, do not exist). Specifically, the temperature-dependent specific heat is overestimated by the calculations as, unlike in the Kondo effect, no entropy is released by Bose populating temperature-independent anticrossings (circles in Fig. 3c). The thermal expansion calculations do not contain the non-trivial temperature dependence of the anharmonicities due to the phonon Kondo interaction, which leaves a corresponding imprint in the thermal expansion difference (stars in Fig. 3c). Finally, the strong Umklapp scattering that is captured by the thermal conductivity calculations does not contain the weakening above TK characteristic of an asymptotically free theory (Fig. 3d).

Further support, independent of any theoretical modeling, comes from recent inelastic neutron scattering experiments. They reveal unexpected changes of the optical dynamical structure factors as function of temperature21 that could be an indication of such a disentanglement of interacting acoustic and rattling modes at high temperatures. All these observations provide strong evidence for a previously unknown correlation effect – an all phononic Kondo effect – as microscopic origin of the peculiar thermodynamic and thermal transport behavior of clathrates.

We do not want to conclude without proposing a possible microscopic realization of the phonon Kondo effect in clathrates. The rattling motion of the guest atoms at the crystallographic 6d site within a soft plane12,31,40 in the tetracaidecahedra (Fig. 1b) is known to have the lowest frequency23. Within this plane, due to the four-fold symmetry of the potential well, rattling occurs preferentially along two perpendicular soft directions22,41,42, which we refer to as 1 and 2. The two corresponding rattling modes (e1 and e2 in Fig. 1b), which are degenerate in energy for symmetry reasons, are thus identified as the pseudospins of the Kondo model (they represent spin-up and spin-down states in the spin Kondo effect). They can be approximated as simple Einstein oscillators, with the first excited state corresponding to the Einstein temperature ΘE observed in inelastic scattering experiments12,13,14. The two polarizations of the transverse acoustic phonons represent the corresponding degree of freedom of the itinerant species (eT1 and eT2 in Fig. 1b, thus representing the conduction electrons in the spin Kondo effect). The hybridization of the local (rattling) and extended (acoustic) phonon modes has been observed in inelastic neutron and X-ray scattering experiments12,13,14,15,34. A spin flip process in the spin Kondo effect corresponds to a scattering process with polarization change in the phonon Kondo effect. It can be visualized as follows: Assume the guest atom rattles in mode e1 and a propagating phonon of polarization eT2 “hops” onto the cage, creating a distortion of the cage that resembles the effect of mode e2. This additional cage distortion will facilitate a change of rattling direction from e1 to e2, and an accompanying change in polarization of the outgoing acoustic wave from eT2 to eT1. Such an interaction of two modes with “opposite” polarization is analogous to an antiferromagnetic exchange interaction in the spin Kondo effect. Further details as well as a suggestion for a mapping of these ingredients onto a Kondo-type Hamiltonian are given in the Supplementary Note 8. We hope that our discovery will be taken up by a broad community of theorists, to develop both ab initio and model-based approaches that can describe the unusual observed phonon properties.

Our discovery of Kondo physics in an all phononic system is not only of fundamental interest (see discussion of non-canonical Kondo physics in other settings in Supplementary Note 8), but also has practical implications. First, it gives a concise description of how to tailor rattling materials for thermoelectric applications at elevated temperatures, which are most relevant for waste heat-recovery applications: Materials with the lowest possible Einstein and thus phonon Kondo temperatures should be found. Microscopically, this might be achieved by changing the mass and size of the guest atoms, but also by structural disorder on the guest site43,44 and/or tailored guest-host charge transfer43.

An equally striking consequence is that Cahill’s definition of the minimum thermal conductivity \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}}^{{\mathrm{min}}}\) (ref. 45), that is being referred to so extensively, needs to be reconsidered. With the energy renormalization also \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}}^{{\mathrm{min}}}\) is drastically reduced (Supplementary Note 1). This implies that for the materials in Fig. 5 there is still room for further improvement as their phonon thermal conductivities all lie well above their respective new \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}}^{{\mathrm{min}}}\) value (dashed red line in Fig. 5). Further lowering the κph of a given material could, for instance, be realized by nanostructuring or the introduction of dense dislocation arrays46. Long-wavelength phonons that are only weakly affected by the phonon Kondo effect could, at high temperatures, be effectively scattered by nanostructures that are small compared to their mean free path. Indeed, a few clathrates and skutterudites appear to violate the original Cahill \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ph}}}^{{\mathrm{min}}}\) limit, though this has not been explicitly recognized in these works (Supplementary Note 2). We expect our results to trigger more systematic efforts along these lines.

The occurrence of low-lying Einstein-like phonon modes that interact with acoustic phonons is not limited to the class of clathrates and related cage-like materials. For the recently discovered family of Cu12−xMxSb4S13 (M = transition metal) tetrahedrites, optical phonon branches involving out-of-plane vibrations of the three-fold coordinated Cu ions were predicted by ab initio calculations and were suggested as origin of the low thermal conductivities47. Interestingly, κph of this material fits perfectly into our universal scaling plot (Fig. 5). Other candidate materials are, e.g., PbTe (ref. 48), Bi2Te3 (ref. 49), BiCu(Se,Te)O (ref. 50), Cu3SbSe3 (ref. 51), and rattling-induced superconductors such as the β-pyrochlore oxides52, dodecaborides53, or VAl10 (ref. 54), and possibly even amorphous and glassy materials55. Detailed investigations, such as presented here, are needed to test whether also in these materials the phonon Kondo effect is at work.

Phonon Kondo systems transfer heat largely via low-frequency phonons of long mean free paths. As such they may be seen as promising intrinsic thermocrystals, for applications such as heat waveguides or thermal diodes in the emerging field of phononics56.

Methods

Synthesis and structural characterization

As starting material for the single crystal growth of BCGGx, two cylindrical rods with the same nominal composition Ba8Cu4.8Ge41.2−x−y□yGax (BCGGx) were prepared for each sample with x = 0.0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 from high-purity elements using a high-frequency induction furnace. One rod with 7 mm in diameter and 60 mm in length served as the feed rod, the other one with the same diameter and 20 mm in length as the seed for the crystal growth. The single crystal growth was performed in a 4-mirror furnace equipped with 1000 W halogen lamps. The pulling speed of the rod was 3–5 mm h−1. Both rods rotated in opposite direction (speed: ~8 revolutions min−1) to ensure efficient mixing of the liquid and a uniform temperature distribution in the molten zone. A pressure of 1.5 bar Ar was used during the crystal growth.

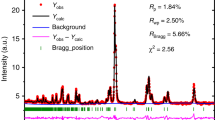

X-ray powder diffraction data on BCGGx were collected using a HUBER-Guinier image plate system (Cu \({\mathrm{K}}_{\alpha _1}\), 8° ≤ 2θ ≤ 100°). The lattice parameters (Fig. 4a) were obtained from least squares fits to indexed 2θ values employing Ge (aGe = 0.5657906 nm) as internal standard.

Thermal conductivity

Commonly used laser flash methods measure the thermal diffusivity and thus need to be combined with specific heat and density measurements to calculate the thermal conductivity, which typically reduces the accuracy of this technique. By contrast, the 3ω method is an ac technique for direct thermal conductivity measurements. During a 3ω experiment the sample is heated locally and thus, in contrast to steady-state heat-flow experiments, errors due to radiation at elevated temperatures are reduced to a negligibly low level24. Furthermore, this method is insensitive to geometrical errors. This is because the only geometrical parameter entering is the length of a line heater. As it is usually prepared by means of photo or electron-beam lithography and sputtering, its length is very well defined (see below). In fact, the error of our 3ω thermal conductivity data, which we estimate to be below 5%, is dominated by uncertainties in the heater resistance and its temperature dependence.

For our studies, the narrow metal line serving as both the heater and the thermometer had a width of 20 μm and a length of 1 mm, with an uncertainly of 1 μm. To avoid electrical contact between heater and sample a thin layer of SiO2 was first deposited on the polished sample surfaces by chemical vapor deposition. Then, a 4 nm thick titanium sticking layer and the 64 nm thick gold film were sputtered in an Ardenne LS 320 S sputter system. The heater structures were made by standard optical lithography techniques using a Karl Suess MJB4 mask aligner.

The metal line was heated by an oscillating current at a circular frequency ω, which thus leads to a 2ω temperature oscillation of both the heater and the sample. Due to the linear temperature dependence of the metallic heater, the 2ω temperature oscillation translates into a 3ω voltage oscillation, which is detected using a lock-in amplifier (7265, Signal Recovery). Applying the 3ω method24 to bulk geometry, the measured in-phase temperature oscillation of the heater/thermometer line is expected to be linear in logarithmic frequency f as long as the thermal penetration depth is large compared to the heater half width b and at least five times smaller than the sample thickness t (see boundaries indicated in Fig. 2a). The thermal conductivity κ of the material can then be extracted from the slope of the in-phase temperature oscillation ΔT vs log f.

Prior to the thermal 3ω voltage detection, the first harmonic and all related higher harmonics are subtracted from the signal using a carefully gain and phase calibrated active filter24 based on a technique that allows to adjust the magnitude and phase of a reference signal as a function of frequency. In this way the main error sources of a 3ω experiment, spurious 3ω signals arising from harmonic distortions of the involved amplifiers, can be largely eliminated. Using an ultra-precise 100 Ω Z-foil resistor (temperature coefficient ±0.05 ppm °C−1, tolerance ±50 ppm; Vishay) as a sample we found the background signal to be negligibly small within the entire frequency range (0.5 Hz to 50 kHz) of the experiment. Using the same resistor, the accuracy of our voltage controlled AC constant current source was found to be ±0.1% within the whole frequency range and for all tested excitations (100 μA to 10 mA). By further measurements on different resistors, load dependences were ruled out.

3ω measurements were done in the temperature range between 80 and 330 K. With this setup, we reproduced the thermal conductivity data on single crystalline Ba8Ga16Ge30 of Sales et al.41 within the error bar, estimated to only 3% in that work. This precision, which is remarkable for a steady-state experiment, was reached with special radiation shields and specific sample geometries41,57.

Below 100 K the data were completed by additional steady-state heat-flow experiments. The phonon thermal conductivities of all investigated materials were calculated by subtracting an electronic contribution, determined using the Wiedemann-Franz law with a constant Lorenz number of L0 = 2.44 · 10−8 WΩK−2 and electrical resistivity data measured on the same samples.

Specific heat

The specific heat was measured with a relaxation-type method using the 4He specific heat option of a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) from Quantum Design. The addenda was measured separately prior to each sample measurement.

To study the phonon contribution to Cp, first the electronic contribution was determined. At low temperatures, the specific heat can be approximated by Cp/T = γ + βT2, where the Sommerfeld coefficient γ represents the electron contribution and the β parameter quantifies the Debye-like phonon contribution. For BCGGx, the data below 3.5 K are very well described by such linear fits (not shown).

Rattling modes, originating from localized oscillations of the guest atoms, can be revealed by analyzing Cp/T3 vs logT. Within such a representation, rattling modes appear as bell-shaped contributions on top of a Debye-like phonon background (not shown).

Hall effect and electrical resistivity

The electrical resistivity and the Hall coefficient were determined by a standard 6-wire technique using the horizontal rotator option of a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) from Quantum Design. Temperature-dependent Hall effect measurements were performed in a magnetic field of 9 T. The Hall resistivity was confirmed to be linear in fields up to 9 T at all temperatures down to 2.5 K. The Hall coefficient was analyzed within a simple one-band model, RH = 1/(ne).

Thermal expansion

Measurements of the coefficient of thermal expansion αL(T) = l−1dl/dT were carried out by using a high-resolution capacitive dilatometer58, which enables the detection of length changes Δl ≥ 10−2 Å. Relative length changes were measured along a principle axis of cubic Ba8Ga16Ge30. αL(T) is obtained by numerical differentiation of the Δl(T)/l data with respect to temperature (Supplementary Note 7).

Ab initio calculations

Ab initio density functional theory (DFT) simulations were conducted using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)59, applying the projector augmented wave method60 and the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) as proposed by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)61.

In a first step, a fully ordered, cubic 54 atom unit cell of Ba8Ga16Ge30 with Ba at the Wyckoff sites 2a and 6d, Ge at 6c and 24k, and Ga at 16i was investigated, using a 5 × 5 × 5 k-point mesh and a plane wave cutoff of 500 eV. For a fixed lattice constant of 10.74 Å, corresponding to the experimental value, the atomic positions were relaxed. To test the impact of a more realistic Ga/Ge distribution22, we have in addition performed selected calculations for a disordered structure (see Supplementary Notes 9 and 11, and Supplementary Fig. 5). After reaching convergence (residual forces of less than 10−3 eV Å−1), symmetry non-equivalent displacements were introduced into the relaxed structure of both the ordered and the disordered (see Supplementary Table 2) unit cell. For displacements of 0.02 Å, the restoring forces were determined, again by using the VASP code with the above described settings. From the obtained forces, the dynamical matrix was extracted and the ALAMODE code23,62 was used to determine the phonon DOS and the specific heat (Supplementary Fig. 1, main parts and insets) in the harmonic approximation.

The thermal expansion coefficient for both the ordered and disordered structure was determined within the quasi-harmonic approximation. For this purpose, the ground state structures and energies were determined for a series of unit cells with lattice parameters, corresponding to both decreased and increased cell volumes. For each of these volumes the dynamical matrix was then obtained in the same way as described above for the experimental volume. By using the phonopy code63 the free energy was determined at the given volume and as a function of temperature. The free energy as a function of volume for a given temperature was then fitted to the Vinet equation of state, again using the phonopy code. Finally, from the free energy minima at a given temperature, the corresponding equilibrium volume at this temperature can be extracted, which then allows to access the thermal expansion coefficient. The ab initio thermal expansion curves are slightly rescaled to match the high-temperature data (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The mode-specific Grüneisen parameter was obtained for both the ordered and the disordered model structures (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Again, the lattice parameter of the equilibrium structure was fixed to the experimental value of 10.74 Å and the dynamical matrix was determined as discussed above. To evaluate the behavior of the vibrational frequencies with respect to a volume change, the dynamical matrix was also determined for increased and decreased lattice parameter (±0.5%). Relating the frequency and volume change of a phonon mode allows then to extract the mode-specific Grüneisen parameter. This procedure is also available within the phonopy code63.

The lattice thermal conductivity of the fully ordered structure was calculated from ab initio results for the anharmonic force constants and by applying the relaxation time approximation, as implemented in the ALAMODE code23,62 (see Supplementary Notes 10 and 11 for details). Our calculations reproduce the temperature dependence of the lattice thermal conductivity obtained by Tadano et al.23 for the same structure model accurately, and the absolute value of the lattice thermal conductivity within a factor of 1.1 (which is most likely due to slightly different lattice constant used in both calculations). Expanding the range of anharmonic interactions from nearest to next-nearest neighbor shells leaves the temperature dependence largely unaffected (for Fig. 3d these results are used). The same is expected if the anharmonic force constants are allowed to vary (within ranges compatible with experiments) with temperature (Supplementary Note 11). Finally, the temperature dependence of the calculated thermal conductivity is shown to be robust against disorder within the Ga-Ge framework (for details see Supplementary Notes 9 and 11 and Supplementary Fig. 5f).

Code availability

Licenses for VASP are available on the VASP website (https://www.vasp.at/). The ALAMODE (https://alamode.readthedocs.io) and phonopy (https://atztogo.github.io/phonopy/) packages are open source.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Slack, G. A. in CRC Handbook of Thermoelectrics Ch. 34 (Eds Rowe, D. M.) 407–440 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1995).

Rowe, D. M. Thermoelectrics Handbook. (CRC/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 2006).

Special Issue: Nanostructured Thermoelectrics (Eds Reith, H. & Nielsch, K.) Phys. Status Solidi A 213, (2016).

Shi, X. & Chen, L. Thermoelectric materials step up. Nat. Mater. 15, 691–692 (2016).

Gorai, P., Stevanović, V. & Toberer, E. S. Computationally guided discovery of thermoelectric materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17053 (2017).

He, J. & Tritt, T. M. Advances in thermoelectric materials research: Looking back and moving forward. Science 357, 1369 (2017).

Takabatake, T., Suekuni, K., Nakayama, T. & Kaneshita, E. Phonon-glass electron-crystal thermoelectric clathrates: Experiments and theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 669–716 (2014).

Nolas, G. S. The Physics and Chemistry of Inorganic Clathrates, Springer Series in Materials Science Vol. 199 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2014).

Lee, C. H., Hase, I., Sugawara, H., Yoshizawa, H. & Sato, H. Low-lying optical phonon modes in the filled skutterudite CeRu4Sb12. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 123602 (2006).

Saramat, A. et al. Large thermoelectric figure of merit at high temperature in Czochralski-grown clathrate Ba8Ga16Ge30. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 023708 (2006).

Takabatake, T. Thermoelectric Nanomaterials, Springer Series in Materials Science Vol. 182, (eds Koumoto, K. & Mori, T.) Ch. 2, 33–49 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Christensen, M. et al. Avoided crossing of rattler modes in thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 811–815 (2008).

Euchner, H. et al. Phononic filter effect of rattling phonons in the thermoelectric clathrate Ba8Ge40+xNi6−x. Phys. Rev. B 86, 224303 (2012).

Pailhès, S. et al. Localization of propagative phonons in a perfectly crystalline solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 025506 (2014).

Tse, J. S. et al. Coupling of localized guest vibrations with the lattice modes in clathrate hydrates. Europhys. Lett. 54, 354–360 (2001).

Cohn, J. L., Nolas, G. S., Fessatidis, V., Metcalf, T. H. & Slack, G. A. Glasslike heat conduction in high-mobility crystalline semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 779–782 (1999).

Nolas, G. S., Weakley, T. J. R., Cohn, J. L. & Sharma, R. Structural properties and thermal conductivity of crystalline Ge clathrates. Phys. Rev. B 61, 3845–3850 (2000).

Graebner, J. E., Golding, B. & Allen, L. C. Phonon localization in glasses. Phys. Rev. B 34, 5696–5701 (1986).

Pohl, R. O. Thermal conductivity and phonon resonance scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 8, 481–483 (1962).

Callaway, J. Model for lattice thermal conductivity at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. 113, 1046–1051 (1959).

Lory, P.-F. et al. Direct measurement of individual phonon lifetimes in the clathrate compound Ba7.81Ge40.67Au5.33. Nat. Commun. 8, 491 (2017).

Christensen, M., Lock, N., Overgaard, J. & Iversen, B. B. Crystal structures of thermoelectric n- and p-type Ba8Ga16Ge30 studied by single crystal, multitemperature, neutron diffraction, conventional X-ray diffraction and resonant synchrotron X-ray diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15657–15665 (2006).

Tadano, T., Gohda, Y. & Tsuneyuki, S. Impact of rattlers on thermal conductivity of a thermoelectric clathrate: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 095501 (2015).

Cahill, D. G. & Pohl, R. O. Thermal conductivity of amorphous solids above the plateau. Phys. Rev. B 35, 4067–4073 (1987).

Bryant, C. A. & Keesom, P. H. Low-temperature specific heat of germanium. Phys. Rev. 124, 698–700 (1961).

Keiber, T. et al. Comparison of local distortions in Ba8Ga16X30 (X = Si, Ge, Sn): an EXAFS study. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 10574–10582 (2015).

Nguyen, L. T. K. et al. Atomic ordering and thermoelectric properties of the n-type clathrate Ba8Ni3.5Ge42.1□0.4. Dalton Trans. 39, 1071–1077 (2010).

Klemens, P. G. The thermal conductivity of dielectric solids at low temperatures. Proc. Roy. Soc. (Lond.) A 208, 108–133 (1951).

May, A. F., Toberer, E. S., Samarat, A. & Snyder, G. J. Characterization and analysis of thermoelectric transport in n-type Ba8Ga16−xGe30+x. Phys. Rev. B 80, 125205 (2009).

Bentien, A. et al. Thermal conductivity of thermoelectric clathrates. Phys. Rev. B 69, 045107 (2004).

Avila, M. A. et al. Glasslike versus crystalline thermal conductivity in carrier-tuned Ba8Ga16Ge30. Phys. Rev. B 74, 125109 (2006).

Suekuni, K., Avila, M. A., Umeo, K. & Takabatake, T. Cage-size control of guest vibrations and thermal conductivity in Sr8Ga16Si30−xGex. Phys. Rev. B 75, 195210 (2007).

Christensen, S. et al. “Glass-like” thermal conductivity gradually induced in thermoelectric Sr8Ga16Ge30 clathrate by off-centered guest atoms. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 185102 (2016).

Tse, J. S., Shpakov, V. P., Murashov, V. V. & Belosludov, V. R. The low frequency vibrations in clathrate hydrates. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 9271–9274 (1997).

Handa, Y. P. & Cook, J. G. Thermal conductivity of xenon hydrate. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6327–6328 (1987).

Gabitto, J. F. & Tsouris, C. Physical properties of gas hydrates: a review. J. Thermodyn. 2010, 271291 (2010).

Stewart, G. R. Heavy-fermion systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 56, 755–787 (1984).

Coleman, P. Introduction to Many-Body Physics. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015).

Desranges, H.-U. & Schotte, K. D. Specific heat of the Kondo model. Phys. Lett. A 91, 240–242 (1982).

Lee, C. H. et al. Neutron scattering study of phonon dynamics on type-I clathrate Ba8Ga16Ge30. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 92, 012169 (2007).

Sales, B. C., Chakoumakos, B. C., Jin, R., Thompson, J. R. & Mandrus, D. Structural, magnetic, thermal, and transport properties of X8Ga16Ge30 (X = Eu, Sr, Ba) single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245113 (2001).

Christensen, M. & Iversen, B. B. Host structure engineering in thermoelectric clathrates. Chem. Mater. 19, 4896–4905 (2007).

He, Y. & Galli, G. Nanostructured clathrate phonon glasses: Beyond the rattling concept. Nano Lett. 14, 2920–2925 (2014).

Sui, F. et al. Synthesis, structure, thermoelectric properties, and band gaps of alkali metal containing type I clathrates: A8Ga8Si38 (A = K, Rb, Cs) and K8Al8Si38. Chem. Mater. 27, 2812–2820 (2015).

Cahill, D. G., Watson, S. K. & Pohl, R. O. Lower limit to the thermal conductivity of disordered crystals. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6131–6140 (1992).

Il Kim, S. et al. Dense dislocation arrays embedded in grain boundaries for high-performance bulk thermoelectrics. Science 348, 109–114 (2015).

Lu, X. et al. High performance thermoelectricity in earth-abundant compounds based on natural mineral tetrahedrites. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 342–348 (2013).

Delaire, O. et al. Giant anharmonic phonon scattering in PbTe. Nat. Mater. 10, 614–619 (2011).

Mansour, A. N. et al. Structural characterization of Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 as a function of temperature using neutron powder diffraction and extended X-ray absorption fine structure techniques. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 083513 (2014).

Vaqueiro, P. et al. The role of copper in the thermal conductivity of thermoelectric oxychalcogenides: do lone pairs matter? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 31735–31740 (2015).

Qiu, W. et al. Part-crystalline part-liquid state and rattling-like thermal damping in materials with chemical-bond hierarchy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15031–15035 (2014).

Nagao, Y., ichi Yamaura, J., Ogusu, H., Okamoto, Y. & Hiroi, Z. Rattling-induced superconductiviy in the β-pyrochlore oxides AOs2O6. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 064702 (2009).

Lortz, R. et al. Specific heat, magnetic susceptibility, resistivity and thermal expansion of the superconductor ZrB12. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024547 (2005).

Klimczuk, T., Szlawska, M., Kaczorowski, D., O’Brien, J. R. & Safarik, D. J. Superconductivity in the Einstein solid VAl10.1. J. Phys. Condens Matter 24, 365701 (2012).

Shintani, H. & Tanaka, H. Universal link between the boson peak and transverse phonons in glass. Nat. Mater. 7, 870–877 (2008).

Maldovan, M. Sound and heat revolutions in phononics. Nature 503, 209–217 (2013).

Sales, B. C., Mandrus, D., Chakoumakos, B. C., Keppens, V. & Thompson, J. R. Filled skutterudite antimonides: Electron crystals and phonon glasses. Phys. Rev. B 56, 15081–15089 (1997).

Pott, R. & Schefzyk, R. Apparatus for measuring the thermal expansion of solids between 1.5 and 380 K. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 16, 444–449 (1983).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Tadano, T., Gohda, Y. & Tsuneyuki, S. Anharmonic force constants extracted from first-principles molecular dynamics: applications to heat transfer simulations. J. Phys. Condens Matter 26, 225402 (2014).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculation. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Vook, F. L. Thermal conductivity of electron-irradiated germanium. Phys. Rev. 138, A 1234–A 1241 (1965).

Bryan, J. D. et al. Nonstoichiometry and chemical purity effects in thermoelectric Ba8Ga16Ge30 clathrate. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 7281–7290 (2002).

Bryan, J. D., Srdanov, V. I., Stucky, G. D. & Schmidt, D. Superconductivity in germanium clathrate Ba8Ga16Ge30. Phys. Rev. B 60, 3064–3067 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Schalko for preparing insulating SiO2 layers and S. Pailhès, V. M. Giordano, M. de Boissieu, P. Coleman, E. Andrei, and M. Foster for insightful discussions. Financial support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF projects TRP176-N22, I623-N16, P29279-N27, DK W1243), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SPP1386, SFB/TR49), and the European Research Council (ERC Adv. Grant 227378 QuantumPuzzle) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.I. and S.P. designed the research. X.Y., P.T. and A.P. synthesized the materials. M.S.I. and R.S. designed the 3ω setup. M.S.I., L.P., X.Y., P.T., G.L., S.H. and E.G. performed the measurements. M.L. supervised the thermal expansion work. M.S.I. analyzed the data. H.E. performed the ab initio calculations. M.S.I. and S.P. interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, M.S., Euchner, H., Yan, X. et al. Kondo-like phonon scattering in thermoelectric clathrates. Nat Commun 10, 887 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08685-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08685-1

This article is cited by

-

Evolution and universality of two-stage Kondo effect in single manganese phthalocyanine molecule transistors

Nature Communications (2021)

-

A theoretical study of 2D AlN on 3D C4H6N6Ni2 clathrate thermoelectric material composites

SN Applied Sciences (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.