Abstract

The nature of the metal-insulator transition in thin films and superlattices of LaNiO3 only a few unit cells in thickness remains elusive despite tremendous effort. Quantum confinement and epitaxial strain have been evoked as the mechanisms, although other factors such as growth-induced disorder, cation non-stoichiometry, oxygen vacancies, and substrate–film interface quality may also affect the observable properties of ultrathin films. Here we report results obtained for near-ideal LaNiO3 films with different thicknesses and terminations grown by atomic layer-by-layer laser molecular beam epitaxy on LaAlO3 substrates. We find that the room-temperature metallic behavior persists until the film thickness is reduced to an unprecedentedly small 1.5 unit cells (NiO2 termination). Electronic structure measurements using X-ray absorption spectroscopy and first-principles calculation suggest that oxygen vacancies existing in the films also contribute to the metal-insulator transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The metal-insulator transition (MIT) in LaNiO3 ultrathin films and superlattices1,2,3,4,5,6 has been proposed to be affected by reduced dimensionaltiy and epitaxial strain, raising the possibility of controlling electronic phases of strong electron correlation materials by nanoscale engineering. In bulk form, LaNiO3 is the only member of the perovskite series RNiO3 (R: rare earth) that is a paramagnetic metal not exhibiting an MIT at any temperature7. In the form of a thin layer, either as a thin film8,9,10 or as a part of a superlattice3,11, it shows insulating behavior (dρ/dT < 0) at room temperature when its thickness is reduced below a few unit cells (u.c.), 2 u.c. being the lowest critical thickness value reported prior to this work4. Numerous prior studies attributed this phenomenon to dimensional crossover4,10 perhaps accompanied by structural distortions5,12,13. It has been suggested that the orbital order in LaNiO3 can be tailored via a combination of reduced dimensionality and epitaxial strain to resemble that of high-temperature cuprate superconductors14,15. Large orbital polarization has been experimentally observed in LaNiO3 superlattices16.

In this work, our first-principles calculations show that dimensionality and strain alone are not sufficient to induce the MIT in LaNiO3 on a LaAlO3 substrate even at one-unit-cell thickness. To reveal the nature of the transition, we use atomic layer-by-layer laser molecular beam epitaxy (ALL-Laser MBE)17 from two separate binary oxide targets (La2O3 and NiO) for LaNiO3 film growth, which allows building up the film one atomic layer at a time under a high oxygen pressure. We find that the LaNiO3 films thus produced remain metallic at room temperature down to a thickness of 1.5 u.c. (NiO2 termination). Electronic structure measurements using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) show a feature in the spectra that has been attributed to apical oxygen vacancies. We conclude that in addition to low dimensionality and strain, oxygen vacancies play an important role in driving the ultrathin LaNiO3 films to become insulating.

Results

Atomic layer-by-layer growth

Figure 1a illustrates the atomic layer-by-layer synthesis of LaNiO3 films on LaAlO3 substrates. Reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) intensity oscillation patterns during growth are shown for a series of LaNiO3 films from 0.5 u.c. to 3.5 u.c. in thickness. The half-integer u.c. denotes NiO2-terminated films while the integer numbers correspond to LaO-terminated films. On a LaAlO3 substrate, a homoepitaxial LaAlO3 buffer layer was first grown, achieved in situ by alternately ablating La2O3 and Al2O3 targets, until the RHEED intensity pattern confirmed a highly crystalline surface. This step ensures the near-ideal epitaxial growth of LaNiO3 starting with the first NiO2 atomic layer (the first half unit cell). Deposition of different number of NiO2 and LaO layers leads to LaNiO3 films with different number of unit cells and termination.

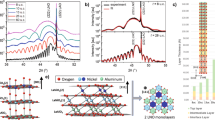

Growth and surface characterization of ultrathin LaNiO3 films. a RHEED intensity oscillation during the growth of the homoepitaxial LaAlO3 buffer layer and 0.5 to 3.5 u.c. of LaNiO3 ultrathin films with both NiO2 and LaO surface terminations. b X-ray reflectometry measurements for a 2 u.c. LaNiO3 film with LaO surface termination. c ABF STEM image of the LaNiO3/LaAlO3 interface in cross-sectional geometry with black atom contrast and drift correction applied. Scale bar, 5 nm. Also shown is the magnification of the interface area with schematic atomic structure overlay identifying both metal and oxygen sites. The LaNiO3 layers exhibited an out of plane expansion of 4 ± 0.5% as compared to the LAO substrate with no measurable in-plane expansion

The ultrathin LaNiO3 films were further characterized by X-ray reflectivity (XRR) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Figure 1b shows a momentum-dependent XRR spectrum for the 2 u.c. LaNiO3 film on a 5 u.c. LaAlO3 buffer layer (open circles) as well as the result of an IMD simulation (solid line) taking into account the roughness at both the surface and interface. The best fit to the spectrum, including the minima positions and the shape of the oscillation, indicates a thickness of 8.0 ± 1.5 Å for the LaNiO3 film and 20.0 ± 2.0 Å for the LaAlO3 buffer layer, in agreement with the growth control parameters. The drift-corrected18 Annular Bright Field (ABF) STEM image of the same sample, obtained in the cross-sectional geometry with black atom contrast, is shown in Fig. 1c. The LaNiO3 layers appear darker due to their higher average Z number. By counting the atomic layers of the LaNiO3 film, we determine that the film thickness is between 2 and 2.5 u.c. The 5 u.c. LaAlO3 homoepitaxial buffer layer is virtually indistinguishable from the underlying LaAlO3 substrate in the STEM image, indicative of its high crystallinity. From the image the out-of-plane lattice constant of the LaNiO3 unit cell is measured to be 3.94 Å, 4 ± 0.5% larger than the in-plane lattice constant. This may represent a volume expansion, which has been attributed previously to oxygen vacancies19,20, although NiO6 octahedral rotations are also known to affect bond angles and lengths in LaNiO3 thin films21. X-ray diffraction reciprocal space map of a 50-u.c.-thick film shows a fully strained film, suggesting that all the LaNiO3 films presented in the work are fully compressively strained to the LaAlO3 substrate.

Metal-insulator transition

Resistivity vs. temperature curves for LaNiO3 films with thicknesses ranging from 1 to 4.5 u.c. are presented in Fig. 2a along with data from a 50 u.c. film. We first focus on the room-temperature resistivity, ρ(300 K), which we classify as metallic or insulating according to the sign of the temperature derivative of the resistivity dρ/dT (positive = metallic; negative = insulating). Our LaNiO3 films show metallic behavior at room temperature down to 2 u.c. We also define the MIT temperature, TMIT, as the temperature at which dρ/dT = 0. Films 3.5 u.c and thicker remain metallic down to the lowest temperature, while thinner films display an MIT in our temperature range, except for the 1 and 1.5 u.c. films which remain insulating up to the highest temperature studied. The critical film thickness for the MIT is 0.5 u.c. less than the smallest value reported previously by King et al.4 We believe the difference from previous results arises from the use of homoepitaxial LaAlO3 buffer layer that reduces defects and from improved oxygenation.

Metal-insulator transition in ultrathin LaNiO3 films. a Temperature-dependent resistivity (ρ) of LaNiO3 films of different thicknesses. b Metal-insulator transition temperature TMIT and c ρ(300 K) of LaNiO3 films with different thicknesses and surface terminations. Open circles indicate that no MIT was observed in the temperature range studied. d DFT and e DFT + DMFT calculations of the DOS of the Ni 3d orbitals for bulk LaNiO3 on the compressive LaAlO3 substrate. f DFT and g DFT + DMFT calculations of the DOS for 1 u.c. and 1.5 u.c. LaNiO3 thin films on the compressive LaAlO3 substrate. The orbital polarization P for each case is indicated. h The imaginary part of the DMFT self-energies of Ni e g orbitals on the Matsubara frequency for 1 u.c. and 1.5 u.c LaNiO3 thin films

The dependence of TMIT and ρ(300 K) on film thickness and surface termination is shown in Fig. 2b, c, respectively. In general, both parameters increase with decreasing LaNiO3 film thickness except that the MIT temperature and resistivity of the 2 u.c. film are lower than the 2.5 u.c. film. Kumah et al. also reported differences between integer and half-integer thicknesses (i.e. NiO2 vs. LaO terminations) albeit at larger film thickneses5. These authors suggest that an ionic buckling in the near-surface NiO2 planes occurs for films terminated with the negatively charged NiO2 plane while they are bulk-like when the films are terminated with the positively charged LaO plane5. We argue here that charge transfer is also important.

Electronic structure calculations

We performed both density functional theory (DFT) and density functional theory plus dynamical mean field theory (DFT + DMFT) calculations of the density of state (DOS) of the Ni 3d orbitals for 1 u.c. (LaO termination) and 1.5 u.c. (NiO2 termination) LaNiO3 films on LaAlO3 substrates. For comparison, the DFT and DFT + DMFT results for bulk LaNiO3 with lattice parameters corresponding to the LaAlO3 substrate-induced strain are shown in Fig. 2d, e, respectively. Just as the bulk LaNiO3 is metallic, both 1 u.c. and 1.5 u.c. films are metallic as well within both DFT (Fig. 2f) and DFT + DMFT (Fig. 2g): the calculations exhibit nonzero spectral weights of Ni e g orbitals at the Fermi energy. However, the metallic state of the 1 u.c. film is marked by a very narrow bandwidth (mass renormalization of about a factor of 4–5) of the 3z2–r2 orbital while the x2–y2 band is effectively two dimensional; these dimensionality and correlation effects suggest that the metallic states are fragile; easily disrupted by disorder, oxygen vacancies, or physics beyond the single-site DMFT approximation used here.

The calculations also reveal the importance of interlayer charge transfer and indicate interesting thickness-dependent electronic phases. We focus first on the 1 u.c. results. At the DFT level, the 1 u.c. LaNiO3 thin film shows enhanced \(d_{3z^2 - r^2}\) hole density relative to \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\). This positive orbital polarization P, defined as

where \(n_{x^2 - y^2}\) and \(n_{3z^2 - r^2}\) represent the number of electrons in orbitals with x2–y2 and 3z2–r2 symmetries, respectively, is due to the strong quantum confinement effect which decreases the bandwidth of the 3z2–r2 orbital relative to that of the x2–y2 orbital, overcoming the level shift (pushing the 3z2–r2 down) from the strain effect and leading to positive orbital polarization. The strong electronic correlations treated in DFT + DMFT reduce the electron kinetic energy, decreasing the effect of quantum confinement. Orbitial polarization is then driven by the level splitting, and has the opposite sign to the prediction of the DFT calculation. The spectra calculated for the 1 u.c. LaNiO3 film are consistent with those of the interfacial layer in (LaNiO3)4/(LaAlO3)4 superlattices computed previously also using DFT+DMFT22.

The electronic structure of the 1.5 u.c. film is more interesting, distinct from either the 1 u.c. layer or bulk. The top layer of the 1.5 u.c. film is terminated as the NiO2 surface and each Ni ion is only five-fold coordinated, with the vacuum interface missing the apical oxygen ion. The missing ion adds charge to the surface bands leading to strong charge transfer and to new physics. We find that the surface layer is an orbital-selective Mott insulator, with the \(d_{3z^2 - r^2}\) orbitals in a Mott insulating state (see the large self-energy shown in Fig. 2h) while the other band is partly filled and incoherent, with carriers strongly scattered by the orbitally selective Mott degrees of freedom (see the suppression of the quasiparticle peak and the large but weakly frequency-dependent self-energy). The bottom layer of the 1.5 u.c. film has six-fold coordinated Ni ions, but is depleted with respect to the top layer. We see a nearly empty 3z2–r2 quasiparticle band (note the very small self-energy) and an effectively two dimensional x2–y2 orbital which may again be susceptible to the localization.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

Detection of oxygen vacancies in thin films is challenging; however, advanced X-ray spectroscopic techniques probing electronic states that can be modified by oxygen vacancies may provide clues23. Figure 3a shows the polarization-averaged XAS results of LaNiO3 films of various thicknesses at the O K edge, which probes the O 2p-projected unoccupied DOSs resulting from dipole-allowed X-ray transitions from the 1s core shell23. The XAS spectra are normalized to zero and unity at the O K pre-edge and post-edge, respectively, and the spectra are shifted vertically for clarity. The pre-edge peak centered at approximately 528 eV (shown in the shaded box in Fig. 3a and normalized in Fig. 3b) reflects the states at the bottom of the unoccupied conduction band via O 2p–Ni 3d orbital hybridization24,25,26. The intensity of the peak is directly related to the hole density, which in the absence of O vacancies depends on the degree of Ni–O hybridization and a higher intensity corresponds to a more metallic LaNiO3 layer26. As seen in the figure, although the intensity of the Ni 4sp feature is relatively constant for all the film thicknesses, the pre-edge peak intensity decreases as the film thickness is reduced, with the reduction being relatively more substantial for the 1.5 and 2 u.c. films. This is consistent with the substantially higher resistivity in the 1.5 and 2 u.c. films (see Fig. 2a, c). The reduction in pre-peak intensity has been attributed to reduced Ni–O hybridization caused by NiO6 octahedral rotations13 or ionic buckling in the near-surface NiO2 planes5, but we suggest that charge transfer driven by O vacancies may also play a role.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy at the oxygen K edge. a X-ray absorption spectra at O-K edge for polarizations parallel (solid line) and perpendicular (dashed line) to the c-axis of the LaNiO3 films. b Normalized polarization-averaged XAS spectra of the oxygen pre-edge region for films with various thicknesses. c Fitting of the pre-edge peak for the 4 u.c. film (green line) using two Gaussian functions (dashed blue line). d Normalized pre-edge peak for 1.5 u.c. films grown at 1, 5, and 7 Pa oxygen pressures, respectively. e Spectral weight of the shoulder peak, Ashoulder/Atotal, where A is the area under the peak, and the energies of the main and shoulder peaks vs. thickness of the LaNiO3 film grown under 7 Pa oxygen pressure. The error bars for the spectral weight are the standard errors of the mean from the Gaussian fitting of the pre-edge peak areas. f Temperature-dependent resistivity curves for 2 u.c. LaNiO3 films grown under oxygen pressures of 1, 5, and 7 Pa, respectively. Red arrow points to the metal to insulator transition temperature for the film grown at 7 Pa

A close examination of the pre-edge peak shape reveals a shoulder on the higher-energy side of the main peak. Figure 3c shows a Gaussian fitting of the pre-edge peak for the 4 u.c. LaNiO3 film that includes both a main peak at about 527.7 eV and a shoulder peak at about 528.7 eV. The shoulder peak has been observed24 in LaNiO2.75 and LaNiO2.5, in which octahedral NiO6 layers alternate with square-planar NiO4 layers27. It was attributed to the Ni3+ ions occupying the square-planar sites and the higher energy was explained by an increase in the charge-transfer energy due to the lower coordination24. In LaNiO3–y with other y values, the intergrowth of the octahedral and square-planar layers is random26. If we see the square-planar NiO4 layers as the octahedral NiO6 layers missing apical oxygen, the existence of the shoulder peak in our LaNiO3 films would indicate oxygen vacancies at the apical sites in the films. We further grew LaNiO3 films at lower oxygen pressures of 1 and 5 Pa with all the other growth conditions kept the same. The spectra for three 1.5 u.c. films grown under 1, 5, and 7 Pa oxygen pressures, respectively, are shown in Fig. 3d. The result shows that the shoulder peak becomes more pronounced in the films grown under lower oxygen pressures, confirming its correlation with oxygen vacancies. These results show that even with the high growth oxygen pressure of 7 Pa and the post-growth annealing in 8.5 × 104 Pa oxygen, oxygen vacancies exist in our LaNiO3 films.

It is difficult to quantify the amount of oxygen vacancies in the LaNiO3 films. However, we can observe the change in the amount of oxygen vacancies with the film thickness by plotting the spectral weight of the shoulder peak, Ashoulder/Atotal, where A is the area under the peak, as a function of film thickness. The result for the 7 Pa growth oxygen pressure is shown in Fig. 3e. It shows that oxygen vacancies exist in the LaNiO3 films of all the thicknesses at roughly the same level, likely uniform throughout the films. Also, shown in Fig. 3e are the energies of the main and shoulder peaks as functions of the film thickness. The peaks move to higher energies as the film thickness decreases, indicating an upward shift of the conduction band, possibly the consequence of a widening of the band gap, which is consistent with a change toward an insulating state. Since all the films are fully strained to the LaAlO3 substrate and the level of oxygen vacancies is roughly the same, the thickness dependence reflects the effect of the dimensional constraint.

The effect of oxygen vacancies on the MIT is shown in Fig. 3f with three 2 u.c. LaNiO3 films grown under different oxygen pressure. A lower growth oxygen pressure leads to a higher resistivity, with the film grown in 7 Pa oxygen being the only one showing metallic behavior at room temperature (the MIT is marked by an arrow). Although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the film quality varied with oxygen pressure during growth, the results in Fig. 3d, f combined strongly suggests that apical oxygen vacancies are associated with the more insulating behavior. In fact, changes in the valence state and O coordination of Ni ions related to the missing of apical oxygen have been suggested as the mechanism of MIT in reduced LaNiO3−y (ref. 28). We thus conclude that in addition to the low dimensionality and epitaxial strain that lead to octahedral rotations13 and ionic buckling5, oxygen vacancies at the apical sites are an important factor in finally driving the few-unit-cell-thick LaNiO3 films insulating.

Orbital polarization

The X-ray linear dichroism (XLD), i.e. the difference between two XAS spectra obtained with different linear polarizations, at the Ni L edge is a sensitive tool for detecting orbital polarization12,29. In bulk LaNiO3, the ground state has Ni in the d8L configuration with eight electrons (seven originating from the Ni d orbitals and one transferred from the O p orbital), with the t2g orbitals being occupied and the e g orbitals, x2–y2 and 3z2–r2, being degenerate1. In thin films, epitaxial strain can lift the e g orbital degeneracy1,14,16, leading to an orbital polarization P. Linearly polarized X-rays can preferentially probe these strongly directional orbitals. Figure 4a shows normalized polarization-dependent XAS spectra at the Ni L2 edge for the 1.5 u.c. and 50 u.c. LaNiO3 films collected at room temperature. The two spectra correspond to photons polarized parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis of the film, respectively, and the XLD signals are marked by the green areas. For the 1.5 u.c. film, the spectrum for the polarization parallel to the c-axis shifts to lower energies relative to that obtained with perpendicular polarization, indicating a splitting of the e g orbitals (Δe g in Fig. 4b). For the 50 u.c. film, the shift also occurs but is much smaller. Figure 4c shows P as a function of film thickness, following the approach established by Wu et al.29 for deriving P from the XLD spectra. The overall negative values of the orbital polarization are consistent with an expansion of the lattice along the direction normal to the film surface under compressive strain14. Below 2 u.c. thickness the value for orbital polarization increases substantially to above 40%. For layer thicknesses exceeding 2 u.c., an oscillation of the orbital polarization with the film termination was observed. Evidently, electronic structure and orbital polarization of the LaNiO3 films are directly impacted by the surface termination and the film thickness as also reported by Kumah et al.5, who cited surface polarization as a reason for such an oscillation. Our DFT + DMFT calculations (Fig. 2g) also show that both the 1 u.c. film and the top layer of the 1.5 u.c. film exhibit negative orbital polarization, although the absolute value of polarization is larger in experiment. Because of the compressive strain of the LaAlO3 substrate and the strongly correlated nature of the \(d_{3z^2 - r^2}\) orbital, the hybridization of the Ni \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital with the O p orbital is increased compared to the Ni \(d_{3z^2 - r^2}\) –O p hybridization and the hole density of the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital is larger than that of the \(d_{3z^2 - r^2}\)orbital. The significantly higher orbital polarization in the LaNiO3 films below 2 u.c. may be a reflection of the importance of the surface polarization as depicted in our theoretical results and suggested by Kumah et al.5

Orbital polarization in the LaNiO3 films. a XAS spectra at Ni L2-edge for E⊥c (blue) and E∥c (red) polarizations and X-ray linear dichroism for a 50 u.c. and a 1.5 u.c LaNiO3 films. Solid lines show the Gaussian fit. b Schematic of the 3d orbitals for the 50 u.c. and 1.5 u.c LaNiO3 films. EF denotes the Fermi energy. c Magnitude of the negative d-orbital polarization vs. film thickness

Discussion

While our DFT + DMFT calculations predict the LaNiO3 ultrathin films to be metallic whereas experimental observation shows that they are insulating, they do show that the metallic states are fragile and could be easily upset by disorder or oxygen vacancies. The top layer of the 1.5 u.c. film reveals strongly reduced and incoherent spectra at the Fermi energy originated from the oxygen vacancy effect due to the absence of the apical oxygen ions. It is plausible that theoretical calculations of the 1 u.c. ultrathin film with oxygen vacancies would yield an insulating state. It is known that oxygen vacancies affect the electronic structures and transport properties in bulk transition-metal oxides30,31. In particular, oxygen vacancies have been shown to induce MIT in LaNiO320,24,28. It was suggested that oxygen vacancies lead to an increase in the Ni2+/Ni3+ ratio and reduction in bandwidths, thus stronger electron correlation and larger Mott–Hubbard splitting20,24,28,32. Our XAS results provide experimental evidence that oxygen vacancies are linked to the MIT in ultrathin LaNiO3 films.

The discovery of oxygen vacancies as a critical factor is important for the fundamental understanding of the MIT in ultrathin LaNiO3 films. Furthermore, oxygen vacancies are an additional parameter to dimensionality and strain for tuning the room-temperature MIT in LaNiO3. For example, electric-field-induced oxygen vacancy formation has been accomplished by electrolyte gating with ionic liquids in VO230. A similar mechanism could turn ultrathin LaNiO3 from showing a metallic to insulating behavior at room temperature, with potential applications in functional devices.

Methods

Sample preparation

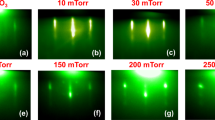

ALL-Laser MBE was used to grow the few-unit-cell-thick LaNiO3 films, which also allows us to investigate the properties of the films with different nominal terminations. We found that on our AlO2-terminated LaAlO3 substrate, prepared by HCl etching followed by annealing at 750 °C in flow of oxygen33, a homoepitaxial LaAlO3 buffer layer is necessary to prepare a high-quality growth template for the ultrathin LaNiO3 films. Ceramic targets of Al2O3, La2O3, and NiO were used. Details for the target preparation can be found in Supplementary Note 1. The ablation was conducted using a KrF excimer laser with 1 Hz repetition rate and 1 J cm−2 energy density. Samples were grown at a temperature of 650 °C in oxygen pressure from 1 to 7 Pa. After the deposition of each LaO or NiO2 layer, a 100-s dwell time was used to oxygenate the film. Most films presented in this work were grown under 7 Pa of oxygen, the highest oxygen pressure we could use. We used RHEED intensity oscillation to control growth, and above 7 Pa the diffraction spots were no longer sharp. To further oxygenate the films, post-growth annealing in 8.5 × 104 Pa of oxygen was performed at the growth temperature of 650 °C for 30 min. See Supplementary Notes 2 and 3 for homoepitaxial LaAlO3 buffer layer and LaNiO3 layer growth and characterization.

Transport measurements

In-plane transport measurements were carried out between 4.2 K and room temperature by using the van der Pauw configuration with contacts at the corners of the films with 5 mm × 5 mm surface area.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

X-ray absorption and linear dichroism measurements were carried out at Beamline 4.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Beamline U4B of the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory in TEY mode with an energy resolution of ∼ 0.1 eV. The average probing depth for soft X-rays in the TEY mode was estimated to be about 5 nm. The X-ray spot was focused down to ∼100-µm diameter in the normal incidence geometry. Samples were characterized using nearly 100% horizontally or vertically polarized X-ray beams at an incidence angle of 15° from the sample plane. In such a grazing measurement geometry the X-ray electric field is oriented parallel to the surface for vertically polarized light, and almost perpendicular to the surface for horizontally polarized light, thus providing maximum sensitivity to changes in orbital character along the different crystallographic axes.

XRR measurement

The XRR measurement was conducted at Beamline X14A of the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The X-ray wavelength was 0.7793 Å. The incident beam size was 0.3 mm (v) x 1.5 mm (h) and the reflectivity was measured using an Si avalanche photodiode detector with a Ge (111) crystal analyzer. The simulation of the reflectivity curves was performed with the IMD code34 available in the XOP package. The layer densities were 7.2 g cm−3 for the LaNiO3 layer and between 5.8 g cm−3 for the LaAlO3 buffer layer.

STEM measurements

TEM samples were prepared by adhering the as-grown LaNiO3 film to a sacrificial Si crystal with M-Bond adhesive. Cross-sectional cuts were made through this stack, and the sample was thinned by mechanical polishing in a wedge geometry followed by final thinning using a Gatan PIPS-II system. All data were acquired on the Titan-class TEAM 0.5 instrument at the Molecular Foundry at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory with geometric aberrations in the probe forming optics corrected to the third order. Data were acquired at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV with a 17 mrad convergence semiangle. The annular bright field collection semiangle was 6–25 mrad and the simultaneously acquired annular dark field images had a collection semiangle angle of 53–270 mrad. Images were recorded in sequential pairs with a 90° rotation offset in order to correct for the linear and nonlinear instrumental drift according to Ophus et al.18. The LaNiO3 lattice parameter was measured by fitting 2D Gaussian functions to the La lattice sites from a mean slab perpendicular to the surface averaged over 20 u.c. parallel to the surface for an improved signal to noise ratio. The bulk LaAlO3 10 u.c. from the surface were used as in internal calibration reference.

First-principles calculation

We adopt DFT for the structural relaxation and both DFT + DMFT and DFT for the DOS calculation in both 1 u.c and 1.5 u.c. LaNiO3 thin films on the LaAlO3 substrate and bulk LaNiO3. We use the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) code for the DFT calculations by taking the exchange-correlation potential to be the generalized gradient approximation using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional. A k-point mesh of 6 × 6 × 1 is used for the slab calculation while the mesh of 6 × 6 × 6 is used for bulk. The plane-wave energy cutoff Ecut is set to be 600 eV. All internal atomic coordinates and the (001) axis lattice parameter of both structures are fully relaxed for both structures while the in-plane lattice constants are fixed. The tetragonal symmetry is imposed during the structural relaxation meaning that the in-plane lattice constants are fixed to the LaAlO3 in-plane constant (~3.81 Å) while the angles between lattice vectors are constrained to be at right angles. Both tilting and rotation of NiO6 octahedra are also allowed as each Ni–O layer contains two Ni ions. We adopt a symmetrical geometry of the slab, namely the vacuum/La-O/Ni-O/LaAlO3/Ni-O/La-O/vacuum geometry for the 1 u.c LaNiO3 film with the La-O layer termination and the vacuum/Ni-O/La-O/Ni-O/ LaAlO3/Ni-O/La-O/Ni-O/vacuum geometry for the 1.5 u.c. LaNiO3 film to avoid the expensive simulation of semi-infinite LaAlO3 layers. The thickness of the LaAlO3 substrate used in both the 1 u.c and 1.5 u.c LaNiO3 film calculations was 6 u.c. for this symmetrical geometry of the slab. The thickness of the vacuum is as large as 6 Å. We have checked that increasing the vacuum thickness to 10 Å does not change the physics discussed in the paper. Namely, it produces a similar DOSs as shown in Fig. 2d.

For DFT + DMFT calculations, we first construct the localized subspace of Ni d and O p orbitals from the DFT band structure spanning the 12 eV energy range of the Ni d and O p band complex by using the maximally localized Wannier function, then perform the DMFT self-consistent calculations for the correlated subspace of Ni d orbitals. We used the continuous time quantum Monte Carlo method35,36 to solve the impurity problem of DMFT. For interaction parameters, we chose the Hubbard interaction U = 5 eV and the Hund’s coupling J = 1 eV.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Scherwitzl, R. et al. Electric-field tuning of the metal-insulator transition in ultrathin films of LaNiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 222114 (2009).

Millis, A. J. & Lau, B. Theory of the magnetic and metal-insulator transitions in RNiO3 bulk and layered structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 126404 (2013).

Boris, A. V. et al. Dimensionality control of electronic phase transitions in nickel-oxide superlattices. Science 332, 937–940 (2011).

King, P. D. C. et al. Atomic-scale control of competing electronic phases in ultrathin LaNiO3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 443–447 (2014).

Kumah, D. P. et al. Effect of surface termination on the electronic properties of LaNiO3 films. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 054004 (2014).

Gabay, M. & Triscone, J. M. Transition-metal oxides: it takes two to waver. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 417–418 (2014).

Torrance, J. B., Lacorre, P., Nazzal, A. I., Ansaldo, E. J. & Niedermayer, C. H. Systematic study of insulator-metal transitions in perovskites RNiO3 (R=Pr,Nd,Sm,Eu) due to closing of charge-transfer gap. Phys. Rev. B 45, 8209–8212 (1992).

Son, J. et al. Low-dimensional Mott material: transport in ultrathin epitaxial LaNiO3 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 062114 (2010).

Scherwitzl, R. et al. Metal-insulator transition in ultrathin LaNiO3 films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 246403 (2011).

Sakai, E., Tamamitsu, M., Yoshimatsu, K., Okamoto, S. & Horiba, K. Gradual localization of Ni 3d states in LaNiO3 ultrathin films induced by dimensional crossover. Phys. Rev. B 87, 075132 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Quantum confinement of Mott electrons in ultrathin LaNiO3/LaAlO3 superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 83, 161102 (2011).

Benckiser, E. et al. Orbital reflectometry of oxide heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 10, 189–193 (2011).

Kumah, D. P. et al. Tuning the structure of nickelates to achieve two-dimensional electron conduction. Adv. Mater. 26, 1935–1940 (2014).

Chaloupka, J. & Khaliullin, G. Orbital order and possible superconductivity in LaNiO3/LaMO3 superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 016404 (2008).

Chen, H. et al. Modifying the electronic orbitals of nickelate heterostructures via structural distortions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 186402 (2013).

Disa, A. S. et al. Orbital engineering in symmetry-breaking polar heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 026801 (2015).

Lei, Q. et al. Constructing oxide interfaces and heterostructures by atomic layer-by-layer laser molecular beam epitaxy. npj Quant. Mater. 2, 10 (2017).

Ophus, C., Ciston, J. & Nelson, C. T. Correcting nonlinear drift distortion of scanning probe and scanning transmission electron microscopies from image pairs with orthogonal scan directions. Ultramicroscopy 162, 1–9 (2016).

Kim, H. S. & Han, M. J. Effect of charge doping on the electronic structure, orbital polarization, and structural distortion in nickelate superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 91, 235102 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Oxygen vacancy induced room-temperature metal-insulator transition in nickelate films and its potential application in photovoltaics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 9769–9776 (2016).

May, S. J. et al. Quantifying octahedral rotations in strained perovskite oxide films. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014110 (2010).

Park, H., Millis, A. J. & Marianetti, C. A. Influence of quantum confinement and strain on orbital polarization of four-layer LaNiO3 superlattices: a DFT+DMFT study. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235109 (2016).

Chandrasena, R. U. et al. Strain-engineered oxygen vacancies in CaMnO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 17, 794–799 (2017).

Abbate, M. et al. Electronic structure and metal-insulator transition in LaNiO3 −δ. Phys. Rev. B 65, 155101 (2002).

De Groot, F. M. F. et al. Oxygen 1s x-ray absorption edges of transition-metal oxides. Phys. Rev. B 40, 5715–5723 (1989).

Suntivich, J. et al. Estimating hybridization of transition metal and oxygen states in perovskites from Ok-edge x-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 1181, 856–1863 (2014).

Sayagués, M. J. et al. Microstructural characterization of the LaNiO3-y system. J. Solid State Chem. 110, 295–304 (1994).

Sanchez, R. D. et al. Metal-insulator transition in oxygen-deficient LaNiO3-x perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 54, 16574–16578 (1996).

Wu, M. et al. Strain and composition dependence of orbital polarization in nickel oxide superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125124 (2013).

Jeong, J. Suppression of metal-insulator transition in VO2 by electric field-induced oxygen vacancy formation. Science 339, 1402–1405 (2013).

Muller, D. A. et al. Atomic-scale imaging of nanoengineered oxygen vacancy profiles in SrTiO3. Nature 430, 657–661 (2004).

Malashevich, A. & Ismail-Beigi, S. First-principles study of oxygen-deficient LaNiO3 structures. Phys. Rev. B 92, 144102 (2015).

Ohnishi, T. et al. A-site layer terminated perovskite substrate: NdGaO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74,, 2531–2533 (1999).

Windt, D. L. IMD—Software for modeling the optical properties of multilayer films. Comput. Phys. 12, 360 (1998).

Werner, P. & Millis, A. J. Hybridization expansion impurity solver: general formulation and application to Kondo lattice and two-orbital models. Phys. Rev. B 74, 155107 (2006).

Haule, K. Quantum Monte Carlo impurity solver for cluster dynamical mean-field theory and electronic structure calculations with adjustable cluster base. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155113 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Work at Temple University was supported by NSF under Grant No. DMR-1245000 (to M.G. and X.X.X.). A.X.G and R.U.C. acknowledge support from the U.S. Army Research Office, under Grant No. W911NF-15-1-0181. The National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Lab was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The authors thank Marissa Libbee for assistance with the TEM sample preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X.X. conceived and designed the experiments, and M.G. and Q.Y.L. carried out the development of the ALL-Laser MBE technique. M.G. fabricated the samples. M.G. and L.K. performed the XRD and transport measurements. A.X.G. designed and supervised the spectroscopic measurements and analyses. R.U.C., G.E.S., D.A.A., P.S., P.O., and E.A. performed the spectroscopic measurements. H.P. and A.J.M. performed the DFT calculations. M.G. and B.A.D. analyzed the spectroscopy data. J.M.B. performed the XRR measurement. P.O. and J.M.B. analyzed the XRR data. J.C. performed the TEM measurements. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golalikhani, M., Lei, Q., Chandrasena, R.U. et al. Nature of the metal-insulator transition in few-unit-cell-thick LaNiO3 films. Nat Commun 9, 2206 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04546-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04546-5

This article is cited by

-

Atomic scale interfacial magnetism and origin of metal-insulator transition in (LaNiO\(_3\))\(_n\)/(CaMnO\(_3\))\(_m\) superlattices: a first principles study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Record high room temperature resistance switching in ferroelectric-gated Mott transistors unlocked by interfacial charge engineering

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Microporous polymer adsorptive membranes with high processing capacity for molecular separation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Oxygen vacancies in nanostructured hetero-interfacial oxides: a review

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2022)

-

A foundation for complex oxide electronics -low temperature perovskite epitaxy

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.