Abstract

Arterial stiffness has been found to be a predictive risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Simple renal cysts are associated with prehypertension, hypertension, diabetes, and increased serum creatinine, which are risk factors of cardiovascular events. The aim of this work was to clarify the association between simple renal cysts and arterial stiffness defined by the brachial and ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV). Subjects with and without simple renal cysts had right baPWV values of 1522.8 ± 357.5 cm/s and 1344.2 ± 268.8 cm/s, respectively (p < 0.001). Based on multiple linear regression analysis, the presence of simple renal cysts was associated with increased baPWV values (p < 0.001). Both the size and the number of simple renal cysts were positively associated with an increased baPWV value. Subjects with a cyst size ≥2 cm (p < 0.001) and a cyst number ≥2 (p < 0.01) had higher baPWV values than those without SRCs. Simple renal cysts are associated with increased arterial stiffness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing evidence that arterial stiffness (AS) is an important predictive risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1]. The gold standard for evaluation of central arterial stiffness is the carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV). In clinical practice, AS is measured through simultaneous oscillometric measurement of the brachial and ankle PWV (baPWV). A close relationship exists between the baPWV and carotid-femoral PWV, which is the gold standard for AS assessment [2]. Furthermore, the baPWV is an independent marker for prediction of future cardiovascular events [1, 2].

Renal cysts are round pouches of fluid that form on or in the kidneys. In general, “simple” renal cysts (SRCs) have thin walls and contain water-like fluid. The prevalence of SRCs varies geographically and increases with age [3]. SRCs are often asymptomatic and rarely require intervention [4]. However, they have been shown to be associated with prehypertension, hypertension, diabetes, and increased serum creatinine [3, 5], which are risk factors of cardiovascular events. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the relationship between SRCs and AS. Thus, the aim of this work was to clarify this association.

Methods

Population

We reviewed data from 7511 examinees who received a health check-up at the Prevention Center of National Cheng Kung University Hospital (NCKUH) between October 2006 and August 2009. Because the analysis was carried out using secondary data without any personal identification information, informed consent was waived. This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of NCKUH in Taiwan (IRB No: B-ER-106–066). A total of 6854 subjects were recruited for the final analysis after excluding subjects with (1) a history of antihypertension medication use (n = 457), lipid-lowering agent use (n = 260), or renal transplantation (n = 2), (2) echo images of polycystic kidney disease (n = 3), renal ectopia (n = 1), any cause of hydronephrosis (n = 24), renal tumor (n = 154), or partial nephrectomy (n = 1), or (3) missing data for other variables (n = 31).

Clinical variables

The baseline variables included the following items: demographic characteristics, medical history, medication use, and lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking, exercise habits, and alcohol consumption). Current smoking and alcohol use were defined as smoking at least 20 cigarettes per month for more than 6 months and consuming at least once drink per week for more than 6 months, respectively. Regular exercise was defined as a minimum of 30 min of exercise at least three times per week.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters) squared. According to the suggestion of the Department of Health in Taiwan, we defined obesity as a BMI ≥27 kg/m2 [6]. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or a positive history of hypertension. Laboratory tests included fasting plasma glucose (FPG), HbA1c, total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). The two-hour postload glucose (2h-PG) was checked with a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test for all participants except for those who were pregnant or had a past history of diabetes. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed if the FPG was ≥126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥6.5%, 2h-PG ≥200 mg/dL or the participant had a past history of diabetes mellitus. The eGFR was calculated based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation, and proteinuria was defined as protein 30 mg/dL or higher in the morning urine using a dipstick test.

SRC measurement

After an overnight fast for at least 8 h, abdominal ultrasonography was performed by experienced physicians using a convex-type real-time electronic scanner (Xario SSA-660A, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Sonographic criteria were used to define SRCs, including (1) absence of internal echoes, (2) posterior enhancement, (3) round/oval shape, and (4) sharp, thin posterior walls [7]. We further classified the SRCs into different categories based on the numbers (<2 and ≥2) and sizes (<2 cm and ≥2 cm) of the cysts.

AS measurement

AS was evaluated from the right side baPWV value, which was calculated as the distance traveled by the pulse wave divided by the time taken to travel the distance and was assessed using an automatically noninvasive vascular screening device (BP-203RPE II; Colin Medical Technology, Komaki, Japan). This measurement was achieved by wrapping four pneumatic pressure cuffs around each of the four extremities that simultaneously measured the blood pressure levels and pulse waves of the brachial artery of both arms and the tibial artery of both legs after 5 min of bed rest.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using the Windows SPSS 17.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL, USA). All data are presented as the means ± standard deviations or percentages. The subjects were classified into groups with and without SRCs. The univariate analyses included Student’s t test for comparison of continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-square test for comparison of categorical variables between groups. We included variables that were possibly related to arterial stiffness or SRCs based on the summary of the literature [1,2,3,4,5] and the statistical significance shown in Table 1 in the multivariate analysis. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess the independent association of the baPWV level with SRCs and its characteristics (number ≥2 and size ≥2 cm) after adjusting for gender, age ≥65 vs. <65 years, BMI ≥27 vs. <27 kg/m2, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TC to HDL-C ratio (≥5 in men, ≥4.5 in women), serum creatinine, current smoking, current alcohol use, and regular exercise. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 6854 subjects were included and divided into two groups based on the presence (n = 888) or absence (n = 5966) of SRCs. The prevalence rates of SRCs were 2.3, 4.7, 9.6, 14.6, 22.6, and 37.2% in subjects <31, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, and >70 years of age. Table 1 shows the comparisons of clinical parameters between subjects with and without SRCs. Significant differences were found in gender, age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, serum creatinine, eGFR, FPG, HbA1c, TC, TG, HDL-C, TC/HDL-C ratio, and the presence of proteinuria, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Moreover, the following parameters were also significantly different between the groups: the presence of SRCs, cyst size ≥2 cm, and total number of cysts ≥2.

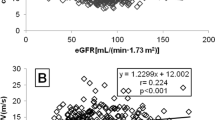

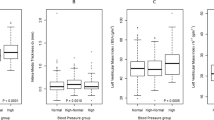

Table 2 reveals the independent relationships between the baPWV value and SRC parameters based on the multiple linear regression analysis. Model 1 showed that a male gender, age ≥65 vs. <65 years, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TC/HDL-C ratio, serum creatinine, and presence of SRCs (β = 56.43, 95% CI: 41.07–71.79, p < 0.001) were positively related to the baPWV value after adjustment for other clinical variables. Model 2 revealed that a size of the renal cyst ≥2 cm (β = 69.23, 95% CI: 43.53–94.94, p < 0.001) was associated with an increased baPWV value. With model 3, cyst numbers <2 (β = 56.33, 95% CI: 40.24–72.43, p < 0.001) and ≥2 (β = 57.19, 95% CI: 15.30–99.09, p < 0.01) were also positively associated with the baPWV value.

In addition, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were used as substitutes for the hypertension status in the multivariate analyses, since the baPWV level is highly dependent on blood pressure. The positive association of the presence of SRCs and their characteristics with the baPWV values was still significant, except that the positive relationship was insignificant between a cyst number ≥2 and the baPWV value when the diastolic blood pressure was considered after adjustment for other variables (data not shown).

Finally, subgroup analyses were performed for the association between SRCs and AS in (1) nonhypertensive vs. hypertensive subjects and (2) nonelderly (<65 years) vs. elderly (≥65 years) subjects. With adjustment for gender, age ≥65 vs. <65 years, BMI ≥27 vs. <27, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, TC to HDL-C ratio (≥5 in men, ≥4.5 in women), eGFR, proteinuria, current smoking, current alcohol use, and regular exercise, the nonhypertensive subjects but not the hypertensive subjects exhibited a positive association of SRCs with the baPWV values. Similarly, the nonelderly had a positive association between SRCs and the baPWV values but the elderly subjects did not, after adjustment for other variables (data not shown). In summary, a significant positive association was found for SRCs with AS, and the association was more apparent in nonelderly and nonhypertensive subjects.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate a positive association between AS, as presented by the baPWV value, and SRCs in a relatively large-sized sample. Our results showed that the presence of SRCs was associated with an increased risk of AS of 56.43 cm/s even after adjusting for other clinical variables. Furthermore, both subjects with a cyst size ≥2 cm and cyst number ≥2 demonstrated higher baPWV values by 69.23 and 57.19, respectively, than subjects without SRCs. According to the increased mean baPWV values mentioned above, the effects of cyst size seem to be greater than those of cyst number with regard to SRCs. However, the 95% CI of the beta coefficient for a cyst size ≥2 cm (43.53–94.94) was included in that of the cyst number (15.30–99.09), and their effects were not significantly different. This result may be related to the higher heterogeneity in the group with a cyst number ≥2. In summary, despite the SRC characteristics, the presence of SRCs is associated with an increase in AS.

In this study, hypertension was also associated with an increased baPWV value. The association between AS and elevated blood pressure is bidirectional. Elevated blood pressure has been found to increase the stress of the arterial wall, which accelerates elastin degradation [8]. AS may increase pressure pulsatility, which is associated with accelerated blood pressure progression and the development of hypertension [8, 9]. Moreover, previous studies have revealed a strong relationship between SRCs and elevated blood pressure, and there is emerging evidence that elevated blood pressure is related to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) by the mass effects of SRCs [3, 5]. Both SRCs and hypertension may be elements of a vicious cycle, because hypertension causes renal dysfunction and thus leads to development of a renal cyst [10, 11]. Although hypertension may be one link between SRCs and AS, factors other than hypertension should be considered for the association between SRCs and AS, because we adjusted for hypertension and many confounding factors in the multivariate analysis.

Two possible major mechanisms (arginine vasopressin (AVP) and low resistance of renal circulation) may support a relationship between SRCs and AS. First, AVP, which is released from the posterior pituitary, promotes water reabsorption in the renal collecting duct, plays an important role in promoting cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) [12] and may be associated with the formation of SRCs [13]. AVP release is also highly sensitive to osmotic stimuli and may be triggered by nonosmotic stimuli (e.g., orthostatic hypotension [14]); this process may be the link to AS, because the baPWV has been found to be an indicator of orthostatic hypotension in clinical practice [15]. The second mechanism involves the unique characteristics of renal circulation, such as low resistance and high flow, which result in greater susceptibility to the barotrauma induced by increases in blood pressure [16]. An increase in large artery stiffness is associated with an increase in transmission of arterial pressure oscillations to the microcirculation and organ damage, including the kidneys [17]. This hemodynamic stress on the kidney vasculature may result in endothelial dysfunction and microvascular ischemia, leading to kidney injury. SRCs originate from the distal convoluted or collecting duct and are thought to arise from renal tubular diverticula or tubular cell hyperplasia secondary to nephron loss [10, 13]. In addition, chronic inflammation and oxidative stress have been found to be associated with an increased risk of ADPKD [18], although further studies are needed to investigate whether chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are possible links between SRCs and AS.

Age and hypertension were found to be positively associated with baPWV in this study, and the results were consistent with those of previous research [8, 9, 19, 20]. Based on age strata of <31, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, and >70 years, the prevalence rates of SRCs were 2.3, 4.7, 9.6, 14.6, 22.6, and 37.2% in this study and 2.4, 3.87, 7.8, 12.2, 19.7, and 35.3% in Chang et al., respectively [21]. This study also found that the significant association of SRCs with arterial stiffness was more apparent in nonelderly and nonhypertensive subjects than in their counterparts. These results may be related to the influence of SRCs on arterial stiffness, which may not be as strong as those of hypertension and the aging process. However, the exact mechanism needs further study. Male subjects had a higher baPWV than females in this study. This finding may be compatible with earlier research, which found lower PWV values in hormone replacement therapy users, because the female hormone is a protective factor for arterial stiffness [22]. In addition, this study revealed that the BMI was inversely associated with the baPWV, which was similar to the results of Budimir et al. [23]. In contrast, previous research showed that the BMI was positively associated with AS [24]. Therefore, the relationship between the BMI and baPWV remains inconclusive; this relationship may be mediated by the intermediate parameters of other cardiovascular risk factors, resulting in high collinearity. Regarding diabetes and the TC/HDL-C ratio, diabetic patients were thought to be related to the inflammatory process and increased oxidative stress [25]. Previous research stated that the TC/HDL-C ratio, which was defined as an optimal “atherogenic index” [26], was a superior measure of risk for coronary heart disease than either the TC or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels [27]. Moreover, the cutoff point of five for the TC/HDL-C ratio in a Chinese population had a higher specificity and accuracy than a LDL-C level of 130 mg/dL [28]. Our study found that a TC/HDL-C ratio ≥5 in men and ≥4.5 in women was positively correlated with the baPWV, which was consistent with previous research [29].

The relationship between the early stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and AS is unclear [30,31,32,33]. Mourad et al. presented a negative association between AS and creatinine clearance [30]. Townsend et al. found that the aortic PWV was significantly and negatively associated with the level of kidney function [31]. The current study revealed that serum creatinine had a positive association with an increased baPWV. However, three studies showed that AS was not associated with CKD [32, 33]. The inconsistent relationship between renal function and AS may be related to the selection of participants in these studies in terms of demographic characteristics and the morbidities that affect AS and the cardiovascular risk.

This study has certain limitations with regard to its results. First, this study adopted a cross-sectional design, making it difficult to clarify the causal relationships between SRCs and the increased AS shown by the baPWV. Second, the subjects were drawn from a Chinese population, and further studies in other ethnicities are needed. Third, the number of SRCs was classified as one and two or more, but the exact number was not available when the number of cysts was greater than two. Although the positive relationship was insignificant between a cyst number ≥2 and the baPWV value when the diastolic blood pressure was considered in the multivariate analysis, the insignificant association might be related to the relatively small number of cases with a cyst number ≥2 (n = 102). As such, whether a higher number of SRCs results in a greater baPWV value is unknown. However, this limitation does not affect the positive relationship between SRCs and AS. Fourth, due to the lack of kidney size data, we could not analyze the role of kidney size in the association between SRCs and arterial stiffness, although intraparenchymal SRCs could decrease nephron numbers and cause hypertension and increased PWV [34]. Finally, in this study, SRCs detected by ultrasound might correspond to category 1 of the Bosniak classification. Although ultrasound has been not utilized to determine the Bosniak classification, this method is widely used for examination of renal cystic lesions detected by computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging [35].

In conclusion, despite the SRC characteristics, the presence of SRCs was associated with an increase in AS, as shown by the baPWV, in this study. Our results provide a direction for further studies on the relationship between SRCs and arterial stiffness, as well as the mechanisms underlying their relationship.

References

Ecobici M, Voiculescu M. Importance of arterial stiffness in predicting cardiovascular events. Rom J Intern Med. 2017;55:8–13.

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, Ioakeimidis N, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2012;60:556–62.

Lee CT, Yang YC, Wu JS, Chang YF, Huang YH, Lu FH, et al. Multiple and large simple renal cysts are associated with prehypertension and hypertension. Kidney Int. 2013;83:924–30.

Desai D, Modi S, Pavicic M, Thompson M, Pisko J. Percutaneous renal cyst ablation and review of the current literature. J Endourol Case Rep. 2016;2:11–13.

Pedersen JF, Emamian SA, Nielsen MB. Simple renal cyst: relations to age and arterial blood pressure. Br J Radiol. 1993;66:581–4.

Pan WH, Flegal KM, Chang HY, Yeh WT, Yeh CJ, Lee WC. Body mass index and obesity-related metabolic disorders in Taiwanese and US whites and blacks: implications for definitions of overweight and obesity for Asians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:31–39.

Weber TM. Sonography of benign renal cystic disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44:777–86.

Zheng X, Jin C, Liu Y, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Kan S, et al. Arterial stiffness as a predictor of clinical hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17:582–91.

Niiranen TJ, Kalesan B, Hamburg NM, Benjamin EJ, Mitchell GF, Vasan RS. Relative contributions of arterial stiffness and hypertension to cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004271.

Terada N, Arai Y, Kinukawa N, Yoshimura K, Terai A. Risk factors for renal cysts. BJU Int. 2004;93:1300–2.

van Varik BJ, Vossen LM, Rennenberg RJ, Stoffers HE, Kessels AG, de Leeuw PW, et al. Arterial stiffness and decline of renal function in a primary care population. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:73–78.

Pinto CS, Reif GA, Nivens E, White C, Wallace DP. Calmodulin-sensitive adenylyl cyclases mediate AVP-dependent cAMP production and Cl- secretion by human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney cells. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2012;303:F1412–1424.

Ponte B, Pruijm M, Ackermann D, Vuistiner P, Guessous I, Ehret G, et al. Copeptin is associated with kidney length, renal function, and prevalence of simple cysts in a population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1415–25.

Zerbe RL, Henry DP, Robertson GL. Vasopressin response to orthostatic hypotension. Etiologic and clinical implications. Am J Med. 1983;74:265–71.

Meng Q, Wang S, Wang Y, Wan S, Liu K, Zhou X, et al. Arterial stiffness is a potential mechanism and promising indicator of orthostatic hypotension in the general population. Vasa. 2014;43:423–32.

Garnier AS, Briet M. Arterial stiffness and chronic kidney disease. Pulse. 2016;3:229–41.

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. The structural factor of hypertension: large and small artery alterations. Circ Res. 2015;116:1007–21.

Menon V, Rudym D, Chandra P, Miskulin D, Perrone R, Sarnak M. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:7–13.

Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:932–43.

Mallareddy M, Parikh CR, Peixoto AJ. Effect of angiotensin-convertingial stiffness in hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2006;8:398–403.

Su TC, Bai CH, Chang HY, You SL, Chien KL, Chen MF, et al. Evidence for improved control of hypertension in Taiwan: 1993-2002. J Hypertens. 2008;26:600–6.

Gompel A, Boutouyrie P, Joannides R, Christin-Maitre S, Kearny-Schwartz A, Kunz K, et al. Association of menopause and hormone replacement therapy with large artery remodeling. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1445–50.

Budimir D, Jeroncic A, Gunjaca G, Rudan I, Polasek O, Boban M. Sex-specific association of anthropometric measures of body composition with arterial stiffness in a healthy population. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CR65–71.

Zebekakis PE, Nawrot T, Thijs L, Balkestein EJ, van der Heijden-Spek J, Van Bortel LM, et al. Obesity is associated with increased arterial stiffness from adolescence until old age. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1839–46.

Mazzone T, Chait A, Plutzky J. Cardiovascular disease risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from mechanistic studies. Lancet. 2008;371:1800–9.

Millán J, Pintó X, Muñoz A, Zúñiga M, Rubiés-Prat J, Pallardo LF, et al. Lipoprotein ratios: physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:757–65.

Kinosian B, Glick H, Preiss L, Puder KL. Cholesterol and coronary heart disease: predicting risks in men by changes in levels and ratios. J Investig Med. 1995;43:443–50.

Wang TD, Chen WJ, Chien KL, Seh-Yi Su SS, Hsu HC, Chen MF, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol levels and ratios in predicting future coronary heart disease in a Chinese population. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:737–43.

Arsenault BJ, Rana JS, Stroes ES, Després JP, Shah PK, Kastelein JJ, et al. Beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: respective contributions of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, and the total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio to coronary heart disease risk in apparently healthy men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:35–41.

Mourad JJ, Pannier B, Blacher J, Rudnichi A, Benetos A, London GM, et al. Creatinine clearance, pulse wave velocity, carotid compliance and essential hypertension. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1834–41.

Townsend RR, Wimmer NJ, Chirinos JA, Parsa A, Weir M, Perumal K, et al. Aortic PWV in chronic kidney disease: a CRIC ancillary study. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:282–9.

Briet M, Collin C, Karras A, Laurent S, Bozec E, Jacquot C, et al. Nephrotest Study Group. Arterial remodeling associates with CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:967–74.

Temmar M, Liabeuf S, Renard C, Czernichow S, Esper NE, Shahapuni I, et al. Pulse wave velocity and vascular calcification at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2010;28:163–9.

Al-Said J, O’Neill WC. Reduced kidney size in patients with simple renal cysts. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1059–64.

Muglia VF, Westphalen AC. Bosniak classification for complex renal cysts: history and critical analysis. Radiol Bras. 2014;47:368–73.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors within the past 36 months. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, HY., Chang, YF., Wu, IH. et al. Simple renal cysts are associated with increased arterial stiffness in a Taiwanese population. Hypertens Res 42, 1068–1073 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0202-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0202-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multiple and large simple renal cysts are associated with glomerular filtration rate decline: a cross-sectional study of Chinese population

European Journal of Medical Research (2024)

-

Prevalence, risk factors and clinical characteristics of renal dysfunction in Chinese outpatients with growth simple renal cysts

International Urology and Nephrology (2022)