Abstract

Introduction:

The glaucomas often co-exist with cataract. We previously reported a large trial of anti-scarring treatment in combined phacotrabeculectomy surgery. Long-term outcomes in an African population are extremely rarely reported. We present here the outcomes in IOP, acuity, bleb morphology and patient perceptions at 3–5-years post surgery.

Methods:

Tanzanian patients with glaucoma and visually significant cataract underwent combined phacotrabeculectomy surgery. In November 2015 an attempt was made to contact all participants in the study inviting them for a repeat examination. All who attended were given a detailed examination. A semi-structured interview in Swahili was administrated to determine patient experience and satisfaction with the surgery.

Results:

Sixty-eight (23%) attended for repeat review in 2015. The mean time from original surgery was 4.5-years (range 2.3–6.6-years). Overall 53 (78%) had IOP < 21 mm Hg and 29 (43%) an IOP < 16 mm Hg at final follow-up. A flat bleb at 26 and 100 days was associated with failure by IOP criteria at 4.5-years post-operatively. A vascular bleb at those time points was not any more associated with late failure than a non-vascular bleb. A majority of patients were pleased with the surgery. The cost of surgery is high but it is a price patients were willing to pay. Nearly all patients (95%) would recommend the service to family and friends.

Discussion:

Owing to the small proportion reviewed, our conclusions are severely limited. Phacotrabeculectomy worked well in a majority of the reviewed population long-term and is accepted by a majority of these patients as worthwhile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Therapy of cataract, the primary cause of preventable blindness in the world, is in many ways straightforward. Patients have symptoms and signs and the therapy is in most instances curative. The glaucomas rank as the second most common cause of preventable blindness. Therapy for this group of diseases is considerably more challenging than for cataract: the damage to the nerve is irreversible, the diseases are largely asymptomatic until it is late/ too late and the therapy is preventive not curative worsening central acuity in the short term in several instances. In contrast to the UK (with some exceptions) there is a relative lack of public awareness about the diseases in Africa [1, 2]. Optimal therapy involves a lifetime of repeat review. A final challenge is that glaucomas frequently co-exist with cataract and glaucoma therapy can result in worsening of cataract requiring further intervention.

Our group have recently reported one solution to some of these challenges in an African context. We undertook a large study of combined cataract and trabeculectomy surgery proving this to both improve vision and result in greatly reduced pressures over a 1-year period.

Long-term outcomes in an African population are extremely rarely reported. This study reports re-examination of as many of the original study cohort as possible a period of 3–5-years post original surgery. Risk factors for failure and attitudes to the surgery were investigated.

Methods

The trial of combined phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy surgery at the CCBRT hospital in Tanzania has been reported elsewhere [3]. The study was approved by the Tanzanian research regulatory body, the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) and registered as NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/717. All patients gave free and informed written consent (signature or thumb print) prior to enrolment in the study. Patient recruitment took place between 9th April, 2009 and 18th October, 2012. The trial was registered with the ISRCT on 30th November, 2009, ISRCTN36436933.

Black African patients were recruited from the general ophthalmology clinic who met the referral criteria (Table 1) and had visually significant cataract (best corrected visual acuity ≤ Snellen’s 6/12 (logMAR 0.3) and a LOCS (Lens Opacities Grading System) III grade of ≥ NC3, ≥ C4 or P3). Having consented to participate they underwent combined phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy surgery. The original study was a randomised controlled trial in which patients were randomised to receive either 1000cG β-radiation or 5 Fluorouracil application per-operatively to the trabeculectomy site.

All enroled patients underwent a detailed clinical assessment. Visual acuity, pin hole acuity and best corrected visual acuity were measured using a reduced logarithm of minimum angle of resolution acuity chart (logMAR). Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using a Goldmann tonometer, which was calibrated and checked at the beginning of each clinic. Three IOP readings were taken per patient at least 30 min apart. Patients who were on IOP lowering medication on referral were asked to stop the medication and to return after 2 weeks. Gonioscopy was done using a four mirror gonio lens. Visual field testing was not routinely performed. Phacotrabeculectomy surgical technique was left to the operating surgeon’s discretion

Subsequent follow-up examinations were scheduled for day 5–7, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months, post operatively. A detailed post-operative assessment was done at each visit, which included bleb assessment, anterior chamber activity, status of the posterior capsule and fundoscopy. IOP was measured twice with an interval between measurements of at least 30 min (Bleb grading system (2017) www.blebs.com). In November 2015 an attempt was made to contact all participants in the study inviting them for a repeat examination. Three attempts were made by our project co-ordinator (IK) to contact each original participant using the details (address and telephone numbers) originally supplied, updated by the most recent clinical records. Of the 301 in the original study 16 had died, 26 had travelled back to their villages, 12 were incorrect telephone numbers, 24 numbers were illegible, 8 were not answering calls, 3 were not physically fit to attend hospital. The remaining 212 agreed to attend. Appointments were given to attend a review clinic held over three continuous days at CCBRT. Travel expenses were reimbursed.

All who attended were given a detailed ophthalmological examination including visual acuity, anterior segment examination, Goldmann tonometry on two occasions separated by 30 min, bleb assessment (modified Moorfields grading system) and photography, fundus examination. A semi-structured interview in Swahili was administrated to determine patient experience and satisfaction with the surgery. The interview consisted of a structured questionnaire with some open-ended questions. This questionnaire was pilot tested and modified following feedback. Translation and back translation had been carried out prior to administration.

The primary outcome was surgical success, defined as an intraocular pressure <16 mm Hg without ocular hypotensive treatment. To aid comparability with other studies in Africa, we also examined a definition of success as an IOP < 21 mm Hg, with or without ocular hypotensive treatment. Secondary outcomes were time to IOP failure, visual acuity, and intra and post-operative complications. Risk factors for failure were examined. The patient satisfaction interviews were transcribed indexed into themes and analysed.

Results

Of the 301 included in the original study, 68 (23%) attended for repeat review in 2015. The demographic and other information of those in the original study and those seen in 2015 are given in Table 2. The mean time from original surgery was 1661 days (range 824–2400, median 1696, SD 421 days) or 4.5-years (range 2.3–6.6-years).

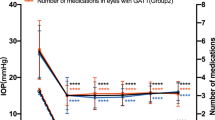

Overall 53 (78%) had IOP < 21 mm Hg and 29 (43%) an IOP < 16 mm Hg at final follow-up. Table 3 shows the outcomes for the two success categories of < 16 mm Hg and < 21 mm Hg by various potential risk factors for failure and clinical observations, which might predict failure. Age, gender, and which antimetabolite was used made no major difference to the final outcome. Use of pre-operative drops was not associated with late failure, however, it should be pointed out that no patient had used drops pre-operatively for longer than 6 months, and most for only a few weeks prior to surgery.

The most interesting finding relates to the bleb morphology. This was done using the full Moorfields grading at 1-year post-operatively. The morphology during the first-year post-operatively was documented in terms of an inflamed bleb and whether the bleb was diffuse, focal or flat. A flat bleb at 26 and 100 days post-operatively was associated with failure by IOP criteria at 4.5-years post-operatively. Interestingly a vascular bleb at those time points did not seem to be any more associated with late failure than a non-vascular bleb.

We had an opportunity to assess the change in bleb morphology over time in relation to success and this is shown in Table 3. It can be seen that two thirds of blebs (41/60 (68%)) retained the same morphological record during this period. Cystic (thin walled) blebs were graded from photographs and there was a similar distribution between the two treatment groups at the 4.5-year post-operative review (5FU group n = 7 (21%), β-radiation group n = 5 (19%), p = 0.85).

The change in acuity from pre-operative assessment to final assessment (4.5-years post surgery range 2.3–6.6-years) was investigated. More than two lines of gain in vision was seen in 18 (26%), no change in 35 (51% and >2 lines of loss in vision in 15 (22%). Patients were examined and a clinical judgement made as to the cause of the acuity change. Of the 15 with more than two lines of acuity worsening over the period, this was considered as a result of ongoing glaucoma damage in six and posterior capsular opacification in a further six. In the remaining three, the causes were vitreous haemorrhage, epiretinal membrane and macular disease.

Patient satisfaction

Sixty-six patients were interviewed over 3 days. Visual acuity was available for 65 patients.

Reasons for surgery

Thirty four (52%) patients thought they had been operated on because they had either high intraocular pressure (IOP) or cataract. Twenty-seven (41%) thought they were operated on because they had both high IOP and cataract. Five (8%) of the patients said they had not been told why they had surgery.

Do you think the operation was successful?

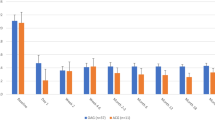

Forty-seven (71%) viewed the operation successful and nine (14%) had mixed feelings. Either their vision had deteriorated since surgery or they had operations in both eyes with success in one and failure in another. Ten (15%) viewed the operation as unsuccessful.

There was a trend for a higher proportion to have poor vision who were unhappy with the operation. Eleven percent [4] of those happy, 22% [2] of those partly happy and 33% [3] of those unhappy with the operation had a visual acuity worse than 1.0 logMAR.

On the day of interview are they happy with their vision?

Over half of the participants (36 (55%)) were happy with their vision on the day of interview, 5 (8%) were happy with one eye and not the other, 3 (5%) were happy but felt their vision was deteriorating, and 20 (30%) were unhappy with their vision on the day.

The success of the operation was not directly related to whether the participant was happy with their vision. See Table 4.

Experiences of surgery

Table 5 shows the patients experiences of surgery

Feeling about their eyes and care now

Thirty-eight (57%) are happy with their eyes and care. Six (9%) are not happy with their vision 5 (8%) feel their vision is getting worse, 11 (17%) said they had poor vision due to cloudiness or tearing. Two (3%) said they felt now the operation was over they werenot getting any service, one (2%) said their eyesight wasnot very good due to medication not being available in their area, two (3%) were still having pain and one (2%) said they were fine apart from the fact their IOP was getting worse.

Money well spent?

Fifty-seven (86%) were happy with the cost. Two (3%) were not happy with the cost. Two (3%) had insurance, three (5%) didnot know. One thought it was expensive but good.

Recommend to family and friends

Sixty-three (95%) would recommend the surgery to family and friends. One said they lived too far away to recommend, one said he couldnot recommend as his surgery had not been successful. One said they think the surgery is out of date and thinks laser would be better. He would not recommend people to come if they had high pressure. Cataract would be ok, he would recommend for that but not pressure.

Discussion

The principal weakness of this report is the fact that only 23% of those originally operated attended for review making the report subject to unquantifiable bias. None-the-less there is such a dearth of long-term data available in this environment we believe this can add some information of use, particularly with the addition of patient perspectives.

A problem with the literature of glaucoma surgery is a lack of standardisation of outcomes. Researchers usually report outcomes by mean IOP reduction and success proportions. While mean IOP reduction may have some place it is a blunt instrument since the pre-operative IOP is subject to variation not only by medical therapy but also disease status. Percentage reduction in IOP has some merit but caries the conundrum that a 50% reduction in IOP from 50 to 25 mm Hg would still not generally be accepted as a successful outcome for the eye. The most accurate reflection of clinical management for outcomes is a success/fail analysis by some pre-determined criterion. The criterion, however, varies between papers and is widely debated. Two of the most widely used criteria are to use 21 mm Hg and 16 mm Hg cutoffs even then, however, papers vary as to whether they include the IOP cutoff (i.e., 21 mm Hg or less or less than 21 mm Hg). The second major challenge in comparing surgical results is the time since surgery since it is well established that this is a major risk factor for failure hence equivalent time points need comparison. Clinical work makes this more difficult since patient cohorts do not attend at accurate 1-year, 2-year or other time points but rather are seen when clinic and patient availability coincide.

Supplemental Table S1 shows outcomes reported for phactorabeculectomy surgery by both outcome measure and time after surgery [4,5,6,7,8,9], [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. If the results of all papers with outcomes of ≤ 21 mm Hg at 36 months are combined then 353/406 = 86.9% (95% CI 83.2–90.0%) were successful [4,5,6,7,8].

This is better than our own finding of 53/68 = 77.9% (95% CI 65.9–86.7%) with IOP ≤ 21 mm Hg. Our findings are, however, for a longer follow-up period and only two of our patients were on topical medications. This is an important point illustrating that phacotrabeculectomy may work well in this population long-term. The results of the other studies relate to patients with and without medications. Three studies gave results without medications. In total 134/194 = 69.1% (95% CI 61.9–75.4%) were successful [5,6,7]. This directly compares with our findings and probably reflects the difficulty our population has in obtaining and affording topical medications.

Results for < 16 mm Hg are similar. Pooled results from three reports show a success proportion of 119/224 (53.1% (95% CI 46.4–59.8%) at 36 months [4, 8, 9] compared to our finding of 29/68 (42.7% (95% CI 30.9–55.2%) failed in our study. Again our follow-up period is longer and the study populations differ.

Another important finding is the acuities 5-years after surgery. Stability of acuity is not so surprising as the cataract surgery was undertaken in more early cases of cataract than is usual in this environment. One-fifth of eyes, however, had visual deterioration. The 6 (9%) with glaucomatous advancement is quite a low proportion given the end-stage nature of disease in a majority of the eyes. As many eyes had severe glaucoma the most appropriate comparator may be the AGIS study, which had similarly severely affected eyes. In the AGIS study, the proportion with visual loss of three lines or more at 5-years of follow-up was 14% in one group and 22% in the other [10]. In other studies of trabeculectomy, visual loss has been seen in a higher proportion of patients, which probably represents cataract development [11].

The 6 (9%) with capsular opacity are important since a simple procedure can restore sight for these. However, access and knowledge that this is all that is required are both limited.

The characterisation of bleb morphology is prone to considerable observer variation. Unsurprisingly presence of a bleb has generally been reported as predictive of success in a trabeculectomy [12].

Attempts to objectively characterise trabeculectomy blebs have been reported by several groups. Bleb inflammation in the first 2–6 weeks has been associated with poorer long-term outcomes for trabeculectomy [12, 13]. In addition, patients of African origin living in the UK were found to have a greater number of conjunctival macrophages and possibly fibroblasts and a tendency for a lower success rate of filtration surgery [14]. Our bleb gradings were performed at 36 and 100 days post op and we found no evidence that inflamed blebs at these time points predicted future outcomes. We do not have data for earlier post-operative time points. Approximately 1/3 of blebs were graded with high vascularity scores after 36 days, suggesting that persistent conjunctival inflammation is common in this population after combined surgery. The more limited use of topical steroid may partially explain this finding. Long-term presence of cystic blebs represents a potential risk factor for bleb leaks and related infections [15]. Both groups have a similar proportion of this bleb type and, therefore, neither antimetabolite is preferred for this reason alone. In a study of betaradiation compared with mitomycin C in South Africa, about one-third of functioning blebs were cystic at 1-year follow-up with no significant difference between the either groups (Cooke et al., 2017. Randomised clinical trial of trabeculectomy with mitomycin-C versus trabeculectomy with beta radiation. (Personal Communication)).

Limitations

Three-hundred and one people were enroled in the study and these are the findings and views of just less than a quarter (23%) of them. This leaves plenty of room for unquantifiable bias. Regrettably, this is common with longer-term follow-up studies, particularly in an African context. The two groups were similar in composition for variables investigated with the exception of the follow-up group having a higher level of education (Table 2). This means any interpretation of the results should be with great care; we do believe it better to have some estimate of long-term outcomes and views than none at all.

In this study, data was translated from Swahili to English at the time of collection, it is possible that information and inclination can get lost in translation, bias can be introduced. Due to time, numbers and translation, the interviews were short and to the point. Probing can be difficult in these situations making the data not as detailed and rich as would be ideal.

Conclusion

This is the first study to our knowledge that presents the views of patients on combined phacotrabeculectomy surgery. The main finding is that the majority of patients were pleased with the surgery and over half were happy with their eyes and care now. Patients were comfortable during the surgery and very few had any pain or discomfort.

The cost of surgery to patients is high but it is a price they were willing to pay and would pay again if required. Nearly all patients (95%) would recommend the service to family and friends.

Of note one patient said they were unable to get drops locally and as a result felt their vision had deteriorated, could this be the case for other patients who did not attend for follow-up.

Summary

What was known before

Cataract and glaucoma frequently co-exist and combined management is challenging particularly in an African context Reports of long-term outcomes of interventions for both in an African population are very rare in the literature Patient views concerning surgical interventions in an African context are rarely documented

What this study adds

Longterm results are given for combined phacotrabeculectomy surgery showing the operation to be effective in retaining vision and preventing blindness A majority of patients were pleased with the surgery.

The cost of surgery is high but it is a price patients were willing to pay.

Nearly all patients (95%) would recommend the service to family and friends

References

Baker H, Cousens SN, Murdoch IE. Poor public health knowledge about glaucoma: fact or fiction? Eye (Lond). 2010;24:653–7.

Murdoch C, Opoku K, Murdoch I. Awareness of glaucoma and eye health services among faith-based communities in Kumasi, Ghana. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:e850–54.

Dhalla K, Cousens S, Bowman R, Wood M, Murdoch I. Is beta radiation better than 5 flurouracil as an adjunct for trabeculectomy surgery when combined with cataract surgery? A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161674.

Chen DZ, Koh V, Sng C, Aquino MC, Chew P. Complications and outcomes of primary phacotrabeculectomy with mitomycin C in a multi-ethnic asian population. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118852.

Rao HL, Maheshwari R, Senthil S, Prasad KK, Garudadri CS. Phacotrabeculectomy without mitomycin C in primary angle-closure and open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2011;20:57–62.

Cagini C, Murdolo P, Gallai R. Longterm results of one-site phacotrabeculectomy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:233–6.

Jin GJ, Crandall AS, Jones JJ. Phacotrabeculectomy: assessment of outcomes and surgical improvements. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1201–8.

Lochhead J, Casson RJ, Salmon JF. Long term effect on intraocular pressure of phacotrabeculectomy compared to trabeculectomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:850–2.

Donoso R, Rodriguez A. Combined versus sequential phacotrabeculectomy with intraoperative 5-fluorouracil. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:71–4.

AGIS investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 12 Baseline risk factors for sustained loss of visual field and visual acuity in patients with advanced glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:499–512.

Agbeja-Baiyeroju AM, Owoaje ET, Omoruyi M. Trabeculectomy in young Nigerian patients. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2002;31:33–5.

Sacu S, Rainer G, Findl O, Georgopoulos M, Vass C. Correlation between the early morphological appearance of filtering blebs and outcome of trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:430–5.

Clarke J, Minassian D, Khaw PT. The More Flow Surgery Study: the effect of interoperative 5FU on IOP control and trabeculectomy bleb appreance using the Moorfields Bleb Grading System. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:1221. (1-5-2005, Abstract)

Broadway D, Grierson I, Hitchings R. Racial differences in the results of glaucoma filtration surgery: are racial differences in the conjunctival cell profile important? Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:466–75.

Yamamoto T, Sawada A, Mayama C, Araie M, Ohkubo S, Sugiyama K, et al. The 5-year incidence of bleb-related infection and its risk factors after filtering surgeries with adjunctive mitomycin C: collaborative bleb-related infection incidence and treatment study 2. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1001–6.

Gopal K, Sahu K, Kumar S, Biakthangi LVL. Efficacy of phacotrabeculectomy alone versus phacotrabeculectomy augmented with autologous anterior capsule implantation beneath the sclera flap, Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33:143–8.

Jung L, Isida-Llerandi CG, Lazcano-Gomez G, SooHoo JR, Kahook MY. Intraocular pressure control after trabeculectomy, phacotrabeculectomy and phacoemulsification in a hispanic population. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2014;8:67–74.

Sengupta S, Venkatesh R, Ravindran RD. Safety and efficacy of using off-label bevacizumab versus mitomycin C to prevent bleb failure in a single-site phacotrabeculectomy by a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Glaucoma. 2012;21:450–9.

Beckers HJ, De Kroon KE, Nuijts RM, Webers CA. Phacotrabeculectomy. Doc Ophthalmol. 2000;100:43–7.

Rodriguez R, Alburquerque R, Sauer T, Batlle JF. The safety and efficacy of two-site phacotrabeculectomy with mitomycin C under retrobulbar and topical anesthesia. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2016;10:7–12.

Ogata-Iwao M, Inatani M, Takihara Y, Inoue T, Iwao K, Tanihara H. A prospective comparison between trabeculectomy with mitomycin C and phacotrabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:e500–1.

Murthy SK, Damji KF, Pan Y, Hodge WG. Trabeculectomy and phacotrabeculectomy, with mitomycin-C, show similar two-year target IOP outcomes. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41:51–9.

Acknowledgements

This project could never have been realised without the assistance of patients and staff at CCBRT Hospital Dar es Salaam Tanzania. The project was funded through grants from BandAid via Fight for Sight and the British Council for the Prevention of Blindness. Technical and logistical assistance from Pak Sang Lee was essential. Erasto Nyakaselula was our translator for the qualitative interviews and Westory Masawe the optometrist who assisted in data collection for the final follow-up. We are extremely grateful to all of the above for their hard work and assistance in ensuring the successful outcome of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Support for project British Council for the Prevention of Blindness (award number 172570) and BandAid via Fight for Sight (award number 162403).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murdoch, I., Baker, H., Odouard, C. et al. Long-term follow-up of phacotrabeculectomy surgery in Tanzania. Eye 33, 1126–1132 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0384-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0384-4