Abstract

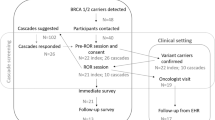

There is an increased pressure to return results from research studies. In Iceland, deCODE Genetics has emphasised the importance of returning results to research participants, particularly the founder pathogenic BRCA2 variant; NM_000059.3:c.771_775del. To do so, they opened the website www.arfgerd.is. Individuals who received positive results via the website were offered genetic counselling (GC) at Landspitali in Reykjavik. At the end of May 2019, over 46.000 (19% of adults of Icelandic origin) had registered at the website and 352 (0.77%) received text message informing them about their positive results. Of those, 195 (55%) contacted the GC unit. Additionally, 129 relatives asked for GC and confirmatory testing, a total of 324 individuals. Various information such as gender and age, prior knowledge of the variant and perceived emotional impact, was collected. Of the BRCA2 positive individuals from the website, 74 (38%) had prior knowledge of the pathogenic variant (PV) in the family. The majority initially stated worries, anxiety or other negative emotion but later in the process many communicated gratitude for the knowledge gained. Males represented 41% of counsellees as opposed to less than 30% in the regular hereditary breast and ovarian (HBOC) clinic. It appears that counselling in clinical settings was more reassuring for worried counsellees. In this article, we describe one-year experience of the GC service to those who received positive results via the website. This experience offers a unique opportunity to study the public response of a successful method of the return of genetic results from research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers, policymakers and ethicists debate the return of findings from genomic research to individual participants [1]. The debate focuses on whether it is appropriate and how to return genomic results to research participants and if so whether all results should be returned or only some of them [2]. Return of results from research testing varies. Within the UK 100,000 Genomes Project (100KGP) participants consent to return of results from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) as well as a limited number of secondary findings. Customers receive their genetic results from direct-to-consumer (DTC) testing, and in some instances the raw data as well. Unrelated to the clinical reason for testing, secondary findings (additionally sought for) are in some cases reported following informed consent in clinical genetic/genomic testing [3]. The American College of Medical Genetics/Association of Molecular Pathology published recommendations of what secondary findings to report in clinical testing in 2013 [4]. These recommendations were revised in 2016 and now include 59 medically actionable genes in which pathogenic variants should be reported back when laboratories undertake genomic testing [3].

In addition, recontacting patients when new information emerges is being discussed and implemented in some clinical settings [5]. The genetic testing landscape is rapidly changing and the models can be diverse. In some cases, genetic counselling is included, in others not [6].

The traditional model is the one where a clinician orders a clinical test, based on clinical observation or family history and the laboratory returns the results back to the clinician. There is a broad range of testing methods and disorders tested for. Genetic counselling is offered in many, but not all cases. Another is the DTC model, where the consumer orders and pays for the test, which is generally cheaper than a clinical test in certified laboratories. The consumer receives the results directly. The testing methods increasingly move from a strictly targeted approach based on specific panels of pathogenic variants in a limited number of genes to exome/genome-wide analysis.

There is also the possibility of using a web-based platform allowing individuals to seek information about their genetic status. This has been done for recessive traits [7, 8] and in some countries patients receive copies of their laboratory results through a website.

The Icelandic BRCA2 founder mutation

deCODE Genetics is a major genomic research company, founded in 1996 and based in Reykjavik, Iceland [9]. It is owned by Amgen, a multinational biopharmaceutical company. According to the company homepage, more than 160.000 Icelanders (over 46% of the population) have participated in their research projects. In Iceland, deCODE Genetics launched a website in May 2018, www.arfgerd.is, where individuals can access their genetic status regarding one Icelandic founder pathogenic variant (PV) in BRCA2. This founder PV is the NM_000059.3:c.771_775del, (commonly referred to as 999del5 in the BRCA2 gene and hereafter referred to as the founder BRCA2 PV) [10], with a carrier frequency of 0.7-0.8% [11]. The service is available for those who have already donated or are willing to donate a sample to deCODE´s biobank and have an Icelandic ID number. Electronic identification, unique to each individual, is needed to sign on to the website. The program has a rigorous mechanism to verify the identity of each sample (sex and inheritance) by comparison to other relatives in the database. The site offers information for users about the founder BRCA2 PV, its prevalence and the associated cancer risk, the inheritance mode, how the results will be provided, why the website was set up and information on how to contact the genetic counselling service at Landspitali. Following consent to the website´s requirements, there is a waiting period of a few weeks before the results are given. The user then receives a text message once the results are ready and signs on again. Those who do not have any sample or no usable sample in the deCODE biobank, are offered to donate a new sample to deCODE, with consent on receiving information on their BRCA2 status.

As was customary the majority of consent forms signed by participants in earlier research done by deCODE, stated that individual research results would not be communicated. By using the arfgerd.is website, individuals agreed to receive results from earlier research samples available in the deCODE database. For several years, deCODE has publicly expressed an interest in reporting genetic research results back to their participants, especially for the founder BRCA2 PV [12]. In December 2016, the Minister of Health appointed a committee to investigate the ethical aspect of this approach, the potential medical benefits for the participants and the implications of communicating genetic information to individuals, with a special emphasis on the BRCA2 founder PV. The committee suggested using a public health portal to enable individuals to query their BRCA2 results from research studies. The portal should include information about the availability of genetic counselling. It was also suggested to have a few days waiting period as it would be helpful to enable people to think further about the possible outcome and its consequences.

In this paper, we describe a one-year clinical experience of a genetic counselling service (GC) at Landspitali, in serving counsellees who received BRCA2 results on this PV from the deCODE website.

Cancer genetic counselling workflow

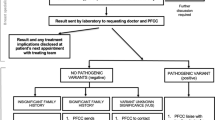

In June 2006, a formal cancer GC unit was established at Landspitali University Hospital LUH [13, 14] The unit’s current workflow in cancer GC for individuals with cancer family history varies slightly depending on knowledge of a PV within the family (Fig. 1). In the case of a strong family history of HBOC, where the founder BRCA PVs are not present, the counsellee is offered a cancer panel test. No genetic testing is offered by the GC service to individuals without a family history and absence of known PV in the family. Normal time for return of results is 7–10 days for a founder PV in the BRCA genes and 4–6 weeks for a cancer panel. Results are mostly given by phone, followed by an information leaflet about the PV, inheritance and management and the counsellee is referred to the appropriate surveillance program [13, 15].

The workflow in cancer GC at Landspitali, is shown in Fig. 1, with the workflow connected to GC for those coming because of arfgerd.is described in line 3 and 4. Those who received positive results from the website had GC by telephone, within 48 h of contacting the GC unit. Fast confirmatory testing was performed for all, males and females, followed by a second GC either by phone or in the clinic based on the counsellee´s preference, where options were discussed, and a surveillance plan organised. During the GC process, counsellees were asked about prior knowledge of the BRCA2 PV in the family and the emotional impact of seeking and getting genetic test results via a website. (Table 1). All information received was recorded in the counsellee´s medical records. The relevant notes were extracted from the records by a healthcare professional conducting the genetic counselling, and each entry classification reviewed by four of the authors.

This work has been approved by the Bioethics Committee at Landspitali (no. 19/2019)

Results

By May 31st 2019, over 46.000 individuals or about 19% of adults of Icelandic origin living in Iceland, had registered on to the website. A little over 17.000 (36%) did not have a usable sample in the biobank and were invited to donate a new sample, which 5000 individuals did before the end of May 2019. About 34.000 individuals received information via text message that their results were available and could be accessed on the website. There was however, no way of knowing how many actually accessed the website to receive their results. Of the 34.000, 352 (1%) were positive [16]. Of those, 195 (55%) contacted the GC unit at Landspitali for GC and were offered confirmatory testing, which is required before establishing surveillance. All test results were concordant. Additionally, 129 relatives of the positive counsellees had contacted the GC unit, in total 324 individuals, 188 (58%) females and 136 (41%) males. The age range was 18-92 years, mean age was 44 years and median 42 years. Of the 352 who tested positive via arfgerd.is, 157 (44%) had not contacted the GC service at Landspitali for confirmatory testing. One reason is that they may have known that they carried the PV prior to signing on to the website arfgerd.is, and therefore they had no need to contact the GC service for confirmatory testing. To explore this an informal poll was presented online to known BRCA2 positive individuals (unpublished results) on a closed social media site. The poll revealed that at least 40 previously clinically tested individuals had sought information from the website.

Verbal communication from the staff in the breast cancer surveillance unit indicated that women using the arfgerd.is method to get information about their BRCA2 status, were more worried and upset than those coming through normal GC. This was despite the fact that everyone had GC at least twice, mostly by phone. The first GC episode was usually before the confirmatory testing and the second followed the test. This was addressed especially both by the GCs and the breast surveillance unit, by increasing clinical appointments and revising the information sheets sent to counsellees.

Of the BRCA2 positive individuals responding to the question whether they had prior knowledge of the BRCA2 variant in their family (n = 172, 88%), 74 (43%) had prior knowledge while 98 (57%) did not. Over half, 97 (57%) did not have a family history of cancer or did not have knowledge of a family history of cancer. Of those responding to the question whether they were surprised to receive the positive results (n = 121, 62%), a total of 46 (38%) said they were, and 61 (50%) were not, while 14 (12%) were unsure. Open questions were asked about emotions following positive results from the website and the main emotion expression was noted. Nearly half (n = 85, 43%) replied. The emotions described were diverse, ranging from positive to negative, including calm, realistic, relief, shock, unrealistic, disbelief and discomfort with the results, fear for relatives, regret, uncertainty, anger and anxiety (Table 1). Fifty-four (63%) of those who replied, expressed some kind of a negative reaction, and 26 (30%), a positive reaction. Examples of the diversity of comments were: “not difficult to know, would have liked to know earlier”, “better to know, than not”, “it is what it is”, and “this is like a death sentence”.

After confirmatory testing and a follow-up testing of relatives, an apparent misattributed parentage was noted in a few cases.

Discussion

Currently, no laws or regulations are available in Iceland regarding the return of genetic testing results to participants in research studies. However, a bill has recently been put forward in the Icelandic parliament that states the necessity of comprehensive information before participation in research, an informed consent and what results will be reported. Further, Iceland has no specific management recommendations for HBOC, but guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) [14] used.

The increased need for counselling and surveillance following the launch of the website www.arfgerd.is was significant, especially given the small size of the units involved at Landspitali. However, given the frequency of this founder variant in Iceland, this launch offered a unique opportunity to study how to best deliver actionable genetic results to a large subset of a single population.

Of those who received notifications of positive results from www.arfgerd.is 56% had contacted the GC unit for confirmatory testing, at the end of May 2019. The process is anonymous and it is therefore not possible to know who of those who registered have accessed their results. The reason for the relatively low number of people coming for confirmatory testing is unknown to the GC unit. It may indicate that some prefer to read up on results themselves, that they will come at a later time, or that the number with prior knowledge of having the PV was higher than estimated. Some may simply have forgotten to obtain their results, and others may be worried and do not want to know their result for the time being. As surveillance depends on confirmatory clinical testing, the confirmation is an important step in the process.

Despite initially expressing negative emotion such as shock or anger, the majority of counsellees said they were thankful for the opportunity to receive the information and to be able to have relevant surveillance.

Nearly half of those contacting the GC service were males. This is interesting as males had comprised no more than 30% of those who had previously sought cancer GC due to HBOC. It is possible that males appreciate the concept of obtaining information via a website better than directly contacting the hospital via phone and/or attending a formal GC session [17]. Also, there was a considerable media coverage about the website, focussing on males. This may have affected the number of males seeking information via the website. Furthermore, it was observed in the clinic, but not formally assessed, that younger males, ages 25–40, who received positive results through the website, were more worried than expected and previously observed. It is possible that the media coverage had an effect, where the high risk of getting cancer and dying was emphasised.

One possible reason for the greater worry and upset among those accessing the test through the website than through regular clinical services was thought to be the absence of pre-test GC, as the purpose of pre-testing GC, is to prepare counsellees for receiving either positive or negative results from the genetic test. Although the website offers comprehensive information, there is no decision aid, such as having to stop and reply to questions to show understanding and determination to continue the procedure. Getting positive results is often difficult, emotionally stressful and psychologically burdensome, but having information about what happens afterwards and a plan for surveillance and management, can lessen potential difficulties. Negative test results can also be difficult due to survivor guilt [18] or because the reason for the cancer(s) in the family has not been found. In the absence of family history, getting a positive genetic result can come as a shock to the recipient. A substantial number of cases did not have a family history of cancer or were unaware of a family history which may explain why they were surprised about the positive results. Pathogenic variants in the BRCA genes have incomplete penetrance affecting cancer history in individual families [19].

GC is regarded as an important part of genetic health services. Initially only done in clinic, GC now uses other ways of communicating information, such as telephone, video-conferencing and web-based technology [20]. The experience described in this article suggests that further research is necessary on how individuals want to receive genetic information. Increasingly, people can and do access their medical records, which can also include laboratory results [21]. Individuals have a right to their own data, as seen in the WHO Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 [22], and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Regulation (EU) 2016/679. The younger generation, and perhaps the older ones as well, are less accepting of delays and may prefer to be e-patients and rather communicate electronically with the doctor or health care professional than wait for a clinical appointment [23]. As for receiving genetic information and genetic counselling, counsellees may want to choose between (a) conventional methods face-to-face, (b) via website/health portal, (c) by video-conferencing, (d) by telephone, (e) by email or a formal letter sent to their homes, or (f) a mixture of the methods above.

The experience of using a website for the return of genetic results was mostly found to work well in Icelandic society and could be used with some modifications in other circumstances. The increased number of males who sought information via the website was especially noteworthy. We conclude that where public health portals are available, as for example in the Scandinavian countries [24,25,26,27] it would be optimal to return genetic results via those channels. Health portals normally lead to securely kept health data, retrieved from various health institutes and possibly from other relevant bodies, allowing access to most or all the health information the individual needs to have through a single site. We would suggest the use of decision aids in the case of sensitive or possibly difficult information, such as genetic test results can be. Using decision aids to prepare people for the possible results has been seen to be helpful to make sure all relevant information is read and understood [28]. However, security must be ensured and there must be robust ways of limiting the risk of the misidentification of samples. As a future development, the use of genealogical data to inform other relatives via the portal might be feasible. Additionally, with a consent from the individual, health professionals could possibly access the health portal and results on their behalf in order to explain their results and individual prognoses and possible preventive measures to their patients. We have no information on those with negative results, whether they had a family history warranting further genetic testing for other pathogenic variants. The website however, suggested that those negative for the BRCA2 PV, could have other genetic causes for inherited breast cancer and should consider genetic counselling. This needs to be addressed when considering web-based reporting of results.

This was a clinical observation within the context of a genetic counselling service. Our results need to be confirmed in larger and more robust studies. Importantly it would be interesting to assess the degree to which subject responses are culture-dependent.

References

Saelaert M, Mertes H, De Baere E, Devisch I. Incidental or secondary findings: an integrative and patient-inclusive approach to the current debate. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:1424–31.

Thorogood A, Dalpe G, Knoppers BM. Return of individual genomic research results: are laws and policies keeping step? Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:535–46.

Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19:249–55.

Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:565–74.

Carrieri D, Howard HC, Benjamin C, Clarke AJ, Dheensa S, Doheny S, et al. Recontacting patients in clinical genetics services: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:169–82.

Middleton A, Mendes Á, Benjamin C, Howard H. Direct to consumer genetic testing: Where and how does genetic counselling fit? Personalized Med. 2017;14:249–57. https://doi.org/10.2217/pme-2017-000

Biesecker BB, Lewis KL, Biesecker LG. Web-based platform vs genetic counselors in educating patients about carrier results from exome sequencing-reply. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:999.

Lewis KL, Umstead KL, Johnston JJ, Miller IM, Thompson LJ, Fishler KP, et al. Outcomes of counseling after education about carrier results: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:540–6.

Stefansson K, Taylor J. Iceland’s genealogy database. Circulation. 2006;114:F103–F4.

Thorlacius S, Olafsdottir G, Tryggvadottir L, Neuhausen S, Jonasson JG, Tavtigian SV, et al. A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied cancer phenotypes. Nat Genet. 1996;13:117–9.

Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Helgason H, Gylfason A, Gudjonsson SA, Zink F, et al. Sequence variants from whole genome sequencing a large group of Icelanders. Sci Data. 2015;2:150011.

Kari Stefansson. „Okkur ber skylda til að vara þetta fólk við“. Rætt við Kára Stefánsson um upplýsingavef ÍE um arfgengi BRCA2 stökkbreytingarinnar,. In: Hávar Sigurjónsson, editor. Iceland: Læknablaðið; 2018.

Stefansdottir V, Skirton H, Johannsson OT, Olafsdottir H, Olafsdottir GH, Tryggvadottir L, et al. Electronically ascertained extended pedigrees in breast cancer genetic counseling. Fam Cancer. 2019;18:153–60.

Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology CoGSoGO. Practice bulletin no 182: hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e110–e26.

Stefansdottir V, Arngrimsson R, Jonsson JJ. Iceland-genetic counseling services. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:907–10.

Brakkasamtökin. Opið hús hjá Brakkasamtökunum,. Iceland: www.visir.is; 2019.

Stamp MH, Gordon OK, Childers CP, Childers KK. Painting a portrait: Analysis of national health survey data for cancer genetic counseling. Cancer Med. 2019;8:1306–14.

Winchester E, Hodgson SV. Psychosocial and ethical issues relating to genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer susceptibility genes. Women’s Health (Lond). 2006;2:357–73.

Thorlacius S, Olafsdottir G, Tryggvadottir L, Neuhausen S, Jonasson JG, Tavtigian SV, et al. A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied cancer phenotypes. Nat Genet. 1996;13:117–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng0596-117

Lynch HT, Snyder C, Stacey M, Olson B, Peterson SK, Buxbaum S, et al. Communication and technology in genetic counseling for familial cancer. Clin Genet. 2014;85:213–22.

Moll, J., Rexhepi, H., Cajander, Å., Grünloh, C., Huvila, I., Hägglund, M., Myreteg, G., Scandurra, I., & Åhlfeldt, R. M. Patients' Experiences of Accessing Their Electronic Health Records: National Patient Survey in Sweden. Journal of medical Internet research, 2018;20:e278. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9492.

Fendall NR. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Lancet 1978;2:1308.

Mesko B, Gyorffy Z. The rise of the empowered physician in the digital health era: viewpoint. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e12490.

Sellberg N, Eltes J. The Swedish Patient Portal and its relation to the National Reference Architecture and the Overall eHealth Infrastructure. In: Aanestad M, Grisot M, Hanseth O, Vassilakopoulou P, editors. Information infrastructures within European health care: working with the installed base. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 225–44.

Kilpelainen K, Parikka S, Koponen P, Koskinen S, Rotko T, Koskela T, et al. Finnish experiences of health monitoring: local, regional, and national data sources for policy evaluation. Global Health Action. 2016;9.

Grisot M, Vassilakopoulou P, Aanestad M. The Norwegian eHealth Platform: development through cultivation strategies and incremental changes. In: Aanestad M, Grisot M, Hanseth O, Vassilakopoulou P, editors. Information infrastructures within European health care: working with the installed base. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 193–208.

Jensen TB, Thorseng AA. Building National Healthcare Infrastructure: the case of the Danish e-Health Portal. In: Aanestad M, Grisot M, Hanseth O, Vassilakopoulou P, editors. Information infrastructures within European health care: working with the installed base. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 209–24.

Kristen McAlpine, Krystina B. Lewis, Lyndal J. Trevena, and Dawn Stacey. What Is the Effectiveness of Patient Decision Aids for Cancer-Related Decisions? A Systematic Review Subanalysis (2018). JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2018;2:1-13

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement for helpful comments: Professor Hans Tomas Björnsson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stefansdottir, V., Thorolfsdottir, E., Hognason, H.B. et al. Web-based return of BRCA2 research results: one-year genetic counselling experience in Iceland. Eur J Hum Genet 28, 1656–1661 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0665-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0665-1

This article is cited by

-

A practical checklist for return of results from genomic research in the European context

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Opportunistic genomic screening. Recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)