Abstract

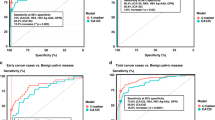

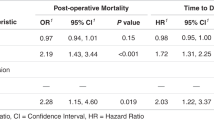

Lung cancer (LC) accounts for the largest number of tumor-related deaths worldwide. As the overall 5-year survival rate of LC is associated with its stages at detection, development of a cost-effective and noninvasive cancer screening method is necessary. We conducted a systematic review to evaluate the diagnostic values of single and panel tumor-associated autoantibodies (TAAbs) in patients with LC. This review included 52 articles with 64 single TAAbs and 19 with 20 panels of TAAbs. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were the most common detection method. The sensitivities of single TAAbs for all stages of LC ranged from 3.1% to 92.9% (mean: 45.2%, median: 37.1%), specificities from 60.6% to 100% (mean: 88.1%, median: 94.9%), and AUCs from 0.416 to 0.990 (mean: 0.764, median: 0.785). The single TAAb with the most significant diagnostic value was the autoantibody against human epididymis secretory protein (HE4) with the maximum sensitivity 91% for NSCLC. The sensitivities of the panel of TAAbs ranged from 30% to 94.8% (mean: 76.7%, median: 82%), specificities from 73% to 100% (mean: 86.8%, median: 89.0%), and AUCs from 0.630 to 0.982 (mean: 0.821, median: 0.820), and the most significant AUC value in a panel (M13 Phage 908, 3148, 1011, 3052, 1000) was 0.982. The single TAAb with the most significant diagnostic calue for early stage LC, was the autoantibody against Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1) with the maximum sensitivity of 90.3% for NSCLC and its sensitivity and specificity in a panel (T7 Phage 72, 91, 96, 252, 286, 290) were both above 90.0%. Single or TAAbs panels may be useful biomarkers for detecting LC patients at all stages or an early-stage in high-risk populations or health people, but the TAAbs panels showed higher detection performance than single TAAbs. The diagnostic value of the panel of six TAAbs, which is higher than the panel of seven TAAbs, may be used as potential biomarkers for the early detection of LC and can probably be used in combination with low-dose CT in the clinic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

LC is one of the most common types of cancer and accounts for the majority of tumor-related deaths globally.

-

Patients diagnosed with LC at an early-stage have a higher 5-year survival rate.

-

Low-dose spiral computed tomography (CT) is the most widely used diagnostic method in clinical practice, but its the high false positive rates and cost may prevent it from becoming a routine screening method.

-

Current research and studies aim to identify the possibility of the molecular makers in body fluids, like TAAbs, for the early detection of LC.

Open questions

-

Currently some TAAbs have been studied. How are they related to diagnosis and how can the appropriate TAAbs for detecting early-stage LC be selected?

-

It is still worth investigating whether the different distributions of TAAbs in the body are long lasting and have high concentration in blood.

-

TAAb detection combined with CT can probably be used in clinic for detection of LC in the future.

-

TAAbs combined with other biomarkers like miRNAs will probably have improved diagnostic performance.

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is one of the most common types of cancer and accounts for the largest number of tumor-related deaths globally. There are an estimated 705,000 cases and 569,000 deaths due to LC in China, and 214,000 cases and 168,000 deaths in US in 20121,2. The overall 5-year survival rate of LC is associated with its stages at doagnosis, which is <20% as the majority of cases are diagnosed at late stages, In contrast, tumors diagnosed at stage IA have a 5-year survival rate of ~70%3. Therefore,early detection and immediate treatment can reduce the mortality of LC significantly. However, the detection and diagnosis of early stage LC is still a challenge, because of the lack of effective screening methods. It has been proven that sputum exfoliative cytologic examination cannot effectively reduce LC mortality4. In contrast, low-dose spiral computed tomography (CT) is highly sensitive at the early detection of small lung nodules and has led to a 20% reduction in LC mortality5, but its high false positive rates and cost may prevent it from becoming a routine screening method4,6.

Thus, it is necessary to develop more cost-effective and noninvasive cancer screening methods. Current research and studies aim to identify molecular makers, that could be detected in body fluids for the early detection of LC. Current diagnostic methods have concentrated on tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) markers, such as the carbohydrate antigen (CA) 125, CA19-9, carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) and alpha fetal protein (AFP), which are effective at diagnosing LC at advanced stages7, but have a low sensitivity and specificity for early stage LC. However, detection of tumor-associated autoantibodies (TAAbs), which are produced by cancer cells against TAAs in blood, may become a potential cancer screening method8. TAAbs are more stable in peripheral blood than TAAs, and have better sensitivity and specificity. Clinical trials evaluating the diagnostic value of TAAbs have shown them to be potential diagnostic method as detective biomarkers for LC, and a series of candidates and multiplex TAAbs have been identified and analyzed.

Hence, we provided a systematic and comprehensive review and summary of the published articles that investigated TAAbs for LC detection. We reported on research results and indicators for assessing the diagnostic performance of TAAbs in the patients’ blood, and also put forward new research problems and new possibilities for future studies9,10,11,12.

Search strategy

Our review was conducted according to a predefined protocol in accordance with the PRISMA statement13. A systematic literature search was performed to identify studies that assessed TAAbs in relation to LC. We searched Pubmed and ISI Web of Science for articles that were published from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2018. The following combinations of search keywords were used to retrieve articles: ((lung OR pulmonary) AND (cancer OR carcinoma OR neoplasm OR tumor OR adenocarcinoma OR squamous carcinoma OR malignancy) AND (autoantibody OR antibody) AND (detection OR diagnosis OR biomarker OR marker) AND (serum OR blood OR plasma))in all fields. Duplicated articles were removed.

Eligibility criteria

We initially read the titles and abstracts to screen the potential eligible articles, with the following exclusion criteria (Fig. 1): (1) non-English articles, (2) non-original articles (reviews, meta-analyses, or proceedings), (3) non-LC studies, (4) nonhuman studies, (5) not related to TAABs, (6) not based on serum or plasma samples, and (7) non-full-text articles. The second round of the preliminary screening involved reading the full-text of the articles, and studies with the following were excluded: (1) diseased controls used, (2) not reporting critical data or no sensitivity, specificity, or area under the curve (AUC).

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Two reviewers (Yiyu Yin and Xiaoyan Li) independently read and extracted all the eligible articles above. Any disagreements and arguments were discussed and resolved among the authors. We extracted the first author, publication year, country, TAAs associated with the autoantibodies, study method, basic population characteristics (including size, age, sex, histological type, and tumor stage), specimen type, targeted TAAbs markers, and evaluation indicators (sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and p-value). Individual TAAbs with a p-value > 0.5 were eliminated. We use Statistical R (version 3.5.1) to calculate the mean or median ages if these statistics were not presented but the raw data were available.

Quality assessment

The quality of each eligible article was assessed by two independent researchers according to quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS-2, www.bris.ac.uk/quadas), using Review Manager (version 5.3). QUADAS-2 contains four domains on bias and applicability of the the research question: (1) patient selection, (2) index test(s), (3) reference standard, and (4) flow and timing, and each item was assessed as “yes” or “no” or “unclear”. Applicability concerns were assessed using the first three domains as well.

Study identification and literature search

A flow process diagram of the study search process is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 8424 potentially relevant publications were identified by the initial independent search using the search terms mentioned above, 5498 from PubMed and 2926 from Web of Science (Fig. 1). 1251 duplicate articles were removed. The titles and abstracts of 7173 articles were screened and a total of 7079 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria described above. Of the remaining 94 full-text articles, 10 were excluded because a disease control was used14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 9 were excluded because they did not have satisfied outcomes24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, and 8 were excluded because of their small sample size (n < 10)33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, Ultimately, 67 articles were included in this systematic review evaluating the diagnostic performance of TAAbs in serum or plasma for LC detection (Tables 1 and 2).

Study quality and characteristics

Study quality was evaluated by two reviewers (Yiyu Yin and Xiaoyan Li) independently. Any academic controversy was resolved by the following discussion among the researchers. All the studies in our research were of high quality with no risk of bias or the concern regarding their applicability, however, there were still unclear risks of bias and unclear applicability in patient selection and index tests in several studies. The statistics of the QUADAS-2 results of the 67 studies are shown in Table 3.

A total of 67 studies are used in the case-control method in which every specimen was collected after LC diagnosis. Of the 67 studies, 52 analyzed single TAAbs (Table 1), 19 evaluated the performance of TAAbs panels (Table 2), 5 of which evaluated the diagnostic value of single TAABs and TAAbs panels at the same time9,10,41,42,43. Detailed information of each study on the number of cases and controls, mean or median age, specimen type, histological subtype, proportion of early-stage LC, detection method, and diagnostic indicators from each study are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Nearly all the included studies collected serum specimens except for 8 studies examined plasma41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Overall, the 67 studies evaluated 64 TAAbs and 20 TAAb panels in plasma or serum. The most commonly used detection method in studies of both single TAAb or with TAAbs panels, was enzyme linked immunoassay (ELISA), which was used in 52 out of 64 studies with single TAAbs and 19 out of 20 studies on TAAbs panels. The other detection methods used were Western blot (WB)50,51, Protein Chip41, serological spot assays52, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and liquid chromatography–electrospray mass spectrometry (LCMS)53. For the commercial panels of mixed TAAbs, the TAAbs were detected with ELISA.

Diagnostic value of single TAAb at all stages of LC

We have listed the single TAAbs used to detect LC in Table 1. In the 52 studies covering 64 specific TAAbs, their sensitivities ranged from 3.1% to 92.9% (mean: 45.2%, median: 37.1%) and their specificities ranged from 60.6% to 100% (mean: 88.1%, median: 94.9%), the AUCs ranged from 0.416 to 0.990 (mean: 0.764, median: 0.785). However, the sensitivity of individual autoantibodies in 27 studies (51.9%) was lower than 50%. Twelve articles reported on the autoantibody against p539,10,51,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62, and found sensitivities ranging from 12.6% to 40.3% and specificities ranging from 94.9% to 100%. Three articles reported on the autoantibody against New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1 (NY-ESO-1), and reported sensitivities from 26.3% to 47%, and specificities from 80.0% to 96.5%63,64,65. Two articles reported on the autoantibody against cyclin B1, with the sensitivities of 13.3% and 20%, and specificities of 96.6% and 97.6%9,10. The single TAAb with the most significant diagnostic value is the autoantibody against 27 Phage with the maximum sensitivity of 92.9% for SCC66.

Diagnostic value of panels of TAAbs at all stages of LC

The diagnostic values of the 20 panels of TAAbs from 19 articles for all LC stages are listed in Table 2. Their sensitivities ranged from 30% to 94.8% (mean: 76.7%, median: 82%), their specificities ranged from 73% to 100% (mean: 86.8%, median: 89.0%), and their AUCs ranged from 0.630 to 0.982 (mean: 0.821, median: 0.820). In two articles, both of the sensitivity and specificity of TAAbs panels were >90.0%. These included panel 5 (IMPDH, phosphoglycerate mutase, ubiquitin, Annexin I, Annexin II, and HSP70-9B)67, and panel 10 (Phage 72, 91, 96, 252, 286, 290)42. The most significant AUC in panel 9 (M13 Phage 908, 3148, 1011, 3052, and 1000) was 0.98242.

Diagnostic value of single TAAbs or panels of TAAbs for early-stage LC

The 11 specific TAAbs (including MUC1, NY-ESO-1, p53, APE1, CD25, CathepsinD, DKK1, WT1, 27Phage, TOPO48, and dickkopf-1 PepB) from 16 studies listed in Table 1. Their sensitivities ranged from 0% to 90.3% (mean: 41.2%, median: 39.3%), and their specificities ranged from 0% to 100% (mean: 91.8%, median: 95.3%). The TAAb with the most significant diagnostic value for detecting early stage LC is the autoantibody against Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1) with a maximum sensitivity of 90.3% for NSCLC68.

The seven studies examining panels of TAAbs for detecting early stage LC were listed in Table 2. They show sensitivities ranging from 0% to 92.2% (mean: 58.3%, median: 62.0%), and specificities ranging from 79.5% to 92.2% (mean: 87.5%, median: 90.0%). Both the sensitivity and specificity in panel 10 (T7 Phage 72, 91, 96, 252, 286, 290) were above 90.0%42.

Prospect of TAAbs as diagnostic biomarkers for LC

We performed a systematic review and identified 67 studies to evaluate the diagnostic performance of serum or plasma single TAAbs or TAAb panels for LC detection. From our results, we proposed that single or multiplex TAAbs may have diagnostic potential for both early stage or any stage of LC. Our results showed that although the great majority of individual TAAbs had low diagnositc sensitivities (Table 1), the TAAb panels supplied relatively high sensitivities, and some panels even had promising sensitivities and specificities (both >90%)42,65. In this present systematic review, our results comfirmed that the panel of 6 and 7 TAAbs had moderate diagnostic accuracy with mean AUCs of 0.850 and 0.806, respectively, at all LC stages, indicating that the diagnostic performance of the panel of six TAAbs at detecting LC was higher than that of the panel of seven TAAbs, However, the studies on the panel of six TAABs did not show any diagnostic values for the patients with early-stage LC except for only one study, which report a great sensitivity of 92.2%42.

Veronesi et al.8 reviewed the advances in LC-related markers, and found that the TAABs and miRNAs (MicroRNA) had great development potential for clinical detection and diagnosis of LC. However, they did not analyze the concrete diagnostic value of different single TAAbs or TAAb panels. Our systematic review found that different single and combinations of multiple TAAbs had different diagnostic performance for all stages of LC, and that more than half of the single TAAbs had low satisfactory diagnostic value with sensitivities lower than 50%. However,the panels of different TAAbs showed higher diagnostic performance with sensitivities ranging from 30.0% to 94.8% (mean: 76.7%, median: 82%), specificities ranging from 73.0% to 100.0% (mean: 86.8%, median: 89.0%), and AUCs ranging from 0.630 to 0.982 (mean: 0.821, median: 0.820). Doseeva et al.65 confirmed the value of using a mixed panel of tumor antigens and autoantibodies in the early detection of NSCLC in high-risk individuals. Their research showed that the use of NY-ESO-1 autoantibodies substantially increased the overall sensitivity of NSCLC detection. With the three tumor markers showing 77% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and a 0.850 AUC, while NY-ESO-1 alone only had 47% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and a 0.600 AUC. This was comfirmed by two studies by Zhang et al. and Park et al.55,69, which indicated that single TAAbs combined with other conventional markers (tumor antigens) were helpful at increasing the sensitivity and specificity for detecting LC. Therefore, while single TAAbs were barely capable of detecting LC at any stag with a high specificity and sensitivity, nevertheless their combinations with other markers could significantly improve their diagnostic value.

In our study, we summarized the studies on three panels42,67,70 containing six different TAAbs, two of which showed good sensitivities of 94.8% and 92.2% and specificities of 91.1% and 92.2%. Farlow et al.71 studied the panel of six TAAbs, which included inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), phosphoglycerate mutase, ubiquillin, Annexin I, Annexin II, and heat shock protein 70-9B (HSP70-9B), and found that its sensitivity for detecting LC was 94.8%. However, the study had a number of limitations, the first of which was that the sample size was too small, with only 10 cases in the experimental group, secondly, the adenocarcinoma was the only pathological subtype included. Therefore, the actual diagnostic value of this panel needs to be further verified. Wu et al.42 included 90 patients with NSCLC, and used an antigen panel of six TAAbs (phage peptide 72, 91, 96, 252, 286, 2906). Compared with the control group, the sensitivity was 92.2% and the specificity was 92.2%. In addition, they tested the serum of 21 early-stage NSCLC patients, and found that the sensitivity was aslo above 90%. They established a six phage peptides detector that could be used to diagnose early-stage NSCLC and discriminate between patients with NSCLC and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD). In order to make sure that the six phage peptide clones had high sensitivities and specificities for NSCLC, the researchers concentrated the NSCLC-specific phage peptide clones using biopannings. The 22 clones that had high reactivity with NSCLC but low reactivity with healthy control were selected for identification of the peptide targets, and the six highest immunoreactive phage clones were selected using individual serum samples of another 30 NSCLC patients. Hence, we indicated that panel of six TAAbs could probably be used to detect LC, especially at the early-stage in the near future. Another study by Boyle et al.72 did not report satisfactory results, with a sensitivity of only 37.0%. The antigens of the panel of six TAAbs they used were p53, NY-ESO-1, CAGE, GBU4-5, Annexin I, and SOX2, p53 is a tumor suppressor gene, which is the most frequently mutated gene in cancer (in addition to LC, it still can be found in breast cancer etc.72), indicating that it plays a crucial role in preventing cancer formation73. However, it can also be detected in some patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)7. Therefore, TAAbs for p53 are nonspecific for LC detection. NY-ESO-1 is a cancer testis antigen, NY-ESO-1 appears to be expressed in 20–25% of NSCLC in most US studies, and SCC is more common in Japan while ADC is dominant in the United States and Europe74, stressing that different pathological subtypes may be involved and give clues to the basis of NY-ESO-1 expression in LC. CAGE is a cancer-associated gene, which expressed in a variety of cancers but not in normal tissues except the testis75, so it could be a target for antitumor immunotherapy. GBU4-5 is also a protein described as inducing autoantibodies in LC76. Annexin I, a phospholipid-binding protein has also been described as including autoantibodies, SOX2 was reported to induce autoantibody responses in SCLC77,78, indicating that autoantibodies to SOX2 could serve as good markers for SCLC, but are not appropriate for NSCLC. Most of the articles had high QUADAS-2 scores, showing that the overall methodological quality of most of the studies were good.

Low-dose CT screenings have the potential to detect early-stage LC and have demonstrated 20% lower LC mortality compared to chest X-ray screenings78. However, it is still difficult to detect LC in high-risk populations using only radiography. So identifying potential biomarkers, like TAAbs, that can be used to detect early-stage LC in a high-risk populations is urgently required, as they could have a distinctly beneficial and clinically significant impact on patient survival12. In our systematic review, several studies were included that reported on single or combinations of multiple TAAbs for detection of early-stage LC. For single TAAbs, the sensitivity for early-stage LC ranged from 0% to 90.3% (mean: 41.2%, median: 39.3%), and the specificities ranged from 0% to 100% (mean: 91.8%, median: 95.3%). One study reported that the autoantibody against Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1) had the maximum sensitivity of 90.3% for NSCLC68. The sensitivities of TAAb panels at detecting early-stage LC patients ranged from 0% to 92.2% (mean: 58.3%,median: 62.0%), and their specificities ranged from 79.5% to 92.2% (mean: 87.5%, median: 90.0%). Although the sensitivities in most of the included studies were below 50.0%, in a study conducted by Wu et al.42, six cancer-associated proteins (Phage peptide 72, 91, 96, 252, 286, and 290) were used as markers of LC with a maximum sensitivity of 92.2% and specificity of 92.2% in 21 patients with stage I–II NSCLC. However, the sensitivity of a seven TAAbs panel (cyclin B1, MDM2, c-Myc, p53, p16, 14-3-3ζ, and NPM1), was 73.3% and its specificity was 79.5%, the panel of CEA, CA-125, and CYFRA21-1 antigens, and NY-ESO-1 antibody, had a sensitivity of 71.2%, in addition, the seven TAAb panels (p53, GAGE7, PGP9.5, CAGE, MAGEA1, SOX2, and GBU4-5), (p53, PGP9.5, SOX2, GAGE7, GBU4-5, CAGE, and MAGEA1), (p53, CAGE, NY-ESO-1, GBU4-5, Annexin I, SOX2, and Hu-D) had sensitivities of 62.0%, 56.4%, and 53.0%, respectively. In conclusion, the diagnostic value of the panel of six TAAbs seems to be higher than the panels of seven TAAbs.

Our study has some deficiencies. First, we just searched Pubmed and ISI Web of Science for articles published from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2018, which may not cover the all relevant studies. Second, we defined stage I LC as early-stage, and a few studies included did not report the exact number of the patients with stage I LC, but stage I–II instead, which may cause some publication bias. Third, the studies included used different methods, which may influence our results. Although some studies did find great diagnostic value for LC, the diagnostic TAABs still cannot be used alone in a clinical setting, as they must be integrated with low-dose CT scan imaging in the screening procedure.

Conclusion

Our study indicated that single TAAbs or TAAb panels may be useful biomarkers for detecting LC patients at all stages or specifically early-stage LC in high-risk populations or healthy people, but the TAAb panels showed a higher diagnostic performance than single TAAbs. The diagnostic value of the panel of six TAAbs is higher than the panels of seven TAAbs, and may be used as potential biomarkers for the early detection of LC and in combination with low-dose CT can probably be used in clinical settings79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105.

References

Torre, L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 87–108 (2015).

Chen, W. Q. et al. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China 2012. China. Cancer 1, 1–8 (2016).

Field, J. K. & Raji, O. Y. The potential for using risk models in future lung cancer screening trials. F1000 Med. Rep. 2 (2010).

Manser, R. et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD001991 (2013).

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 5, 395–409 (2011).

Jennifer, M. C., Stuart, G. B., Pamela, M. M., Jonathan, D. C. & Kramer, B. S. Cumulative incidence of false-positive test results in lung cancer screening. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 505–512 (2012).

Tarro, G., Perna, A. & Esposito, C. Early diagnosis of lung cancer by detection of tumor liberated protein. J. Cell. Physiol. 1, 1–5 (2015).

Giulia, V., Fabrizio, B., Maurizio, I. & Marco, A. The challenge of small lung nodules identified in CT screening: can biomarkers assist diagnosis? Biomark. Med. 1 (2016).

Pei, L. et al. Evaluation of serum autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens as biomarkers in lung cancer. Tumor Biol. 10, 1–10 (2017).

Dai, L. P. et al. Serological proteome analysis approach-based identification of ENO1 as a tumor-associated antigen and its autoantibody could enhance the sensitivity of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in the detection of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 22, 36664–36673 (2017).

Muren, H. H. et al. A novel antibody-drug conjugate, HcHAb18-DM1, has potent anti-tumor activity against human non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 513 (2019).

Okano, T. et al. Identification of haptoglobin peptide as a novel serum biomarker for lung squamous cell carcinoma by serum proteome and peptidome profiling. Int. J. Oncol. 3, 945–952 (2016).

David, M., Alessandro, L., Jennifer, T. & Douglas, G. A., The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 7, 1–6 (2016).

Yanagita, K. et al. Serum anti-Gal-3 autoantibody is a predictive marker of the efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy against pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Asian Pac. J. Cancer P. 17, 7959–7965 (2015).

Mendell, J. et al. Clinical translation and validation of a predictive biomarker for patritumab, an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 3 (HER3) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine 3, 264–271 (2015).

Ohue, Y. et al. Prolongation of overall survival in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients with the XAGE1 (GAGED2a) antibody. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 5052–5063 (2014).

Li, H., Zhang, A., Hao, Y., Guan, H. & Lv, Z. Coexistence of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome and autoimmune encephalitis with anti-CRMP5/CV2 and anti-GABAB receptor antibodies in small cell lung cancer: a case report. Med. (Baltim.). 19, e0696 (2018).

Titulaer, M. J. et al. SOX antibodies in small-cell lung cancer and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: frequency and relation with survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 4260–4267 (2009).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Anti-HuC and -HuD autoantibodies are differential sero-diagnostic markers for small cell carcinoma from large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. Int. J. Oncol. 6, 1957–1962 (2012).

Tetsuya, M. et al. Clinical implications of p53 autoantibodies in the sera of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1563–1568 (1998).

Murray, P. V. et al. Serum p53 antibodies: predictors of survival in small-cell lung cancer? Br. J. Cancer 83, 1418–1424 (2000).

Fumihiro, T. et al. Evaluation of angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer: comparison between anti-CD34 antibody and anti-CD105 antibody. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 3410–3415 (2001).

Jennifer, S. et al. Lack of association between serum antibodies of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and the risk of lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 123, 2469–2471 (2008).

Liu, C. Y., Xie, W. G., Wu, S., Tian, J. W. & Li, J. A comparative study on inflammatory factors and immune functions of lung cancer and pulmonary ground-glass attenuation. Eur. R. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 4098–4103 (2017).

Campa, M. J., Gottlin, E. B., Herndon, J. E. & Patz, E. F. Rethinking autoantibody signature panels for cancer diagnosis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 1011–1014 (2017).

Broodman, I. et al. Survivin autoantibodies are not elevated in lung cancer when assayed controlling for specificity and smoking status. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 165–172 (2016).

Graham, F. H. et al. Signal stratification of autoantibody levels in serum samples and its application to the early detection of lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 5, 618–625 (2013).

Schneider, J. et al. p53 protein, EGF receptor, and anti-p53 antibodies in serum from patients with occupationally derived lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 80, 1987–1994 (1999).

Michael, B. et al. The role of circulating anti-p53 antibodies in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and their correlation to clinical parameters and survival. BMC Cancer 4, 1–6 (2004).

Ann, M. E., Joel, W., Stephanie, R. L. & Olivera, J. F. Evaluation of anticyclin B1 serum antibody as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for lung cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1062, 29–40 (2005).

Sissel, E. M., Lars, D., Geir, O. S., Jan, H. A. & Christian, A. V. CRMP5 antibodies in patients with small-cell lung cancer or thymoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 57, 227–232 (2008).

Ashraf, A. et al. A highly sensitive particle agglutination assay for the detection of p53 autoantibodies in patients with lung cancer. Cancer 110, 2502–2506 (2007).

Nakajima, M. et al. CV2/CRMP5-antibody-related paraneoplastic optic neuropathy associated with small-cell lung cancer. Intern. Med. 11, 1645–1649 (2018).

Zeng, Y. et al. A sandwich-type electrochemical immunoassay for ultrasensitive detection of non-small cell lung cancer biomarker CYFRA21-1. Bioelectrochemistry 120, 183–189 (2018).

Geevasinga, N., Burrell, J. R., Hibbert, M., Vucic, S. & Ng, K. C9ORF72 familial motor neuron disease − frontotemporal dementia associated with lung adenocarcinoma and anti-Ma2/Ta antibodies: a chance association? Eur. J. Neurol. 4, e31–e33 (2014).

Nagashio, R. et al. Detection of tumor-specific autoantibodies in sera of patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer 3, 364–373 (2008).

Kazuhiro, T., Hiroaki, I., Naomi, K., Toyokazu, S. & Hisayuki, K. Anti-Hu antibody in a patient with Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome and early detection of small cell lung cancer. Intern. Med. 34, 1082–1085 (1995).

Richard, L. et al. Serum p53 antibodies as early markers of lung cancer. Nat. Med. 1, 701–702 (1995).

Marina, S. S. et al. Antirecoverin autoantibodies in the patient with non-small cell lung cancer but without cancer-associated retinopathy. Lung Cancer 41, 363–367 (2003).

Ryo, N. et al. Detection of tumor-specific autoantibodies in sera of patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer 62, 364–373 (2008).

Khattar, N. H., Coe-Atkinson, S. P., Stromberg, A. J., Jett, J. R. & Hirschowitz, E. A. Lung cancer-associated auto-antibodies measured using seven amino acid peptides in a diagnostic blood test for lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 267–272 (2014).

Wu, L. et al. Development of autoantibody signatures as novel diagnostic biomarkers of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Comparative study of autoantibody responses between lung adenocarcinoma and benign pulmonary nodules. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11, 334–345 (2016).

Chapman, C. J. et al. Autoantibodies in lung cancer: possibilities for early detection and subsequent cure. Thorax 3, 228–233 (2008).

Wang, W. L., Zhong, W., Chen, C., Meng, Q. & Wei, J. Circulating antibodies to linear peptide antigens derived from ANXA1 and FOXP3 in lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 6, 3151–3155 (2017).

Lui, N. S. et al. SULF2 expression is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker in lung cancer. PLoS One 2, e0148911 (2016).

Ye, L. et al. A study of circulating anti-CD25 antibodies in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 8, 633–637 (2013).

Cherneva, R., Petrov, D., Georgiev, O. & Trifonova, N. Clinical usefulness of alpha-crystallin antibodies in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 10, 14–17 (2010).

Zhao, H., Zhang, X., Han, Z. & Wang, Y. Circulating anti-p16a IgG autoantibodies as a potential prognostic biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer. FEBS Open Bio 8, 1875–1881 (2018).

Luo, X. et al. Comparative autoantibody profiling before and after appearance of malignance: identification of anti-cathepsin D autoantibody as a promising diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 4, 704–709 (2012).

Myrna, R. R. et al. Serum anti-p53 antibodies and prognosis of patients with small-cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 89, 381–385 (1997).

Wu, W. B. et al. An autoantibody against human DNA-topoisomerase I is a novel biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 105, 1664–1670 (2018).

de Costa, D. et al. Peptides from the variable region of specific antibodies are shared among lung cancer patients. PLoS One 9, e96029 (2014).

Mattioni, M. et al. Prognostic role of serum p53 antibodies in lung cancer. BMC Cancer 1 (2015).

Park, Y., Kim, Y., Lee, J. H., Lee, E. Y. & Kim, H. S. Usefulness of serum anti-p53 antibody assay for lung cancer diagnosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 12, 1570–1575 (2011).

Mack, U., Ukena, D., Montenarh, M. & Sybrecht, G. W. Serum anti-p53 antibodies in patients with lung cancer. Oncol. Rep. 7, 669–674 (2000).

Jerzy, L. et al. Prognostic value of serum p53 antibodies in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 22, 191–200 (1998).

Toshihiko, I., Takehiko, F., Yukio, S., Kenzo, H. & Hidemi, O. Serum anti-p53 autoantibodies in primary resected non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 46, 345–349 (1998).

Ewa, J. et al. Serum p53 antibodies in small cell lung cancer: the lack of prognostic relevance. Lung Cancer 31, 17–23 (2001).

Cioffi, M. et al. Serum anti-p53 antibodies in lung cancer: comparison with established tumor markers. Lung Cancer 33, 163–169 (2001).

Monica, N. et al. Serum anti-p53 autoantibodies in pleural malignant mesothelioma, lung cancer and non-neoplastic lung diseases. Lung Cancer 39, 165–172 (2003).

Suleeporn, S., Adisak, S., Gun, C. & Thierry, S. Serum p53 antibodies in patients with lung cancer: correlation with clinicopathologic features and smoking. Lung Cancer 39, 297–301 (2003).

Mysikova, D. et al. Case-control study: smoking history affects the production of tumor antigen-specific antibodies NY-ESO-1 in patients with lung cancer in comparison with cancer disease-free group. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2, 249–257 (2017).

Yang, J. H., Jiao, S. C., Kang, J. B., Rong, L. & Zhang, G. Z. Application of serum NY-ESO-1 antibody assay for early SCLC diagnosis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 11, 14959–14964 (2015).

Doseeva, V., Colpitts, T., Gao, G., Woodcock, J. & Knezevic, V. Performance of a multiplexed dual analyte immunoassay for the early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Transl. Med. 13, 55 (2015).

Leidinger, P. et al. Toward an early diagnosis of lung cancer: an autoantibody signature for squamous cell lung carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 123, 1631–1636 (2008).

Surget, S., Khoury, M. P. & Bourdon, J. C. Uncovering the role of p53 splice variants in human malignancy: a clinical perspective. OncoTargets Ther. 7, 57–68 (2013).

Oji, Y. et al. WT1 IgG antibody for early detection of nonsmall cell lung cancer and as its prognostic factor. Int. J. Cancer 125, 381–387 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Autoantibodies against insulin-like growth factorbinding protein-2 as a serological biomarker in the diagnosis of lung cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 1, 93–100 (2013).

Ren, S. et al. Early detection of lung cancer by using an autoantibody panel in Chinese population. Oncoimmunology 7, e1384108 (2018).

Farlow, E. C. et al. Development of a multiplexed tumor-associated autoantibody-based blood test for the detection of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 3452–3462 (2010).

Boyle, P. et al. Clinical validation of an autoantibody test for lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 22, 383–389 (2011).

Gnjatic, S. et al. NY‐ESO‐1: Review of an immunogenic tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1–30 (2016).

Cho, B. et al. Identification and characterization of a novel cancer/testis antigen gene CAGE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292, 715–726 (2012).

Krause, P. et al. SeroGRID: an improved method for the rapid selection of antigens with disease related immunogenicity. J. Immunol. Methods 283, 261–267 (2003).

Brichory, F. M. et al. An immune response manifested by the common occurrence of annexins I and II autoantibodies and high circulating levels of IL-6 in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9824–9829 (2010).

Vural, B. et al. Frequency of SOX Group B (SOX1, 2, 3) and ZIC2 antibodies in Turkish patients with small cell lung carcinoma and their correlation with clinical parameters. Cancer 103, 2575–2583 (2005).

Kovalchik, S. A. et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 245–254 (2013).

Dai, L. et al. Identification of autoantibodies to ECH1 and HNRNPA2B1 as potential biomarkers in the early detection of lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 5, e1310359 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Development and application of a double-antibody sandwich ELISA kit for the detection of serum MUC1 in lung cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 4, 369–376 (2016).

Qi, S. et al. Autoantibodies to chromogranin A are potential diagnostic biomarkers for non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 12, 9979–9985 (2015).

de Mello, R. A., Lamy, P. J., Plassot, C. & Pujol, J. L. Serum HE4: an independent prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE 6 (2015).

Wang, W. et al. Detection of circulating antibodies to linear peptide antigens derived from ANXA1 and DDX53 in lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 5, 4901–4905 (2014).

Ma, L. et al. Serum anti-CCNY autoantibody is an independent prognosis indicator for postoperative patients with early-stage nonsmall-cell lung carcinoma. Dis. Markers 35, 317–325 (2013).

Gangopadhyay, N. et al. Early detection of NSCLC with scFv selected against IgM autoantibody. PLoS ONE 4 (2013).

Dai, N. et al. Serum APE1 autoantibodies: a novel potential tumor marker and predictor of chemotherapeutic efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 3, e58001 (2013).

Liu, L. et al. Are circulating autoantibodies to ABCC3 transporter a potential biomarker for lung cancer? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 10, 1737–1742 (2013).

Yao, X. et al. Dickkopf-1 autoantibody is a novel serological biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer. Biomarkers 2, 128–134 (2010).

Pilyugin, M. et al. BARD1 serum autoantibodies for the detection of lung cancer. PLoS One 12, e0182356 (2017).

Jung, J. Y. et al. Ratio of autoantibodies of tumor suppressor AIMP2 and its oncogenic variant is associated with clinical outcome in lung cancer. J. Cancer 8, 1347–1354 (2017).

Zhang, L., Wang, H. & Dong, X. Diagnostic value of alpha-enolase expression and serum alpha-enolase autoantibody levels in lung cancer. J. Bras. Pneumol. 44, 18–23 (2018).

Shen, L. et al. Combined detection of dickkopf-1 subtype classification autoantibodies as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 10, 3545–3556 (2017).

Li, P. et al. Serum anti-MDM2 and anti-c-Myc autoantibodies as biomarkers in the early detection of lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 5, e1138200 (2016).

Dai, L. et al. Autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens in the early detection of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 99, 172–179 (2016).

Jia, J. et al. Development of a multiplex autoantibody test for detection of lung cancer. PLoS One 9, e95444 (2014).

Du, Q. et al. Significance of tumor-associated autoantibodies in the early diagnosis of lung cancer. Clin. Respir. J. 12, 2020–2028 (2018).

Chapman, C. J. et al. Immunobiomarkers in small cell lung cancer: potential early cancer signals. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 1474–1480 (2011).

Qiu, J. et al. Occurrence of autoantibodies to annexin I, 14-3-3 theta and LAMR1 in prediagnostic lung cancer sera. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 5060–5066 (2008).

Mikio, O. et al. Autoantibody to heat shock protein Hsp40 in sera of lung cancer patients. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 92, 316–320 (2001).

Tsuji, K. et al. Detection of the circulating lung cancer marker LeAP with a new monoclonal antibody TRD-L1. Int. J. Biol. Markers 12, 49–54 (1997).

Mitchell, L. M., Bhavna, D., Edward, G. & Brain, S. S. Frequency and clinical implications of monoclonal antibody detection of tumor-associated antigens in serum of patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer Diagn. 142, 1059–1062 (1990).

Li, Z. et al. Antibodies to HSP70 and HSP90 in serum in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Detect. Prev. 27, 285–290 (2003).

Li, Z. et al. Identification of circulating antibodies to tumor-associated proteins for combined use as markers of non-small cell lung cancer. Proteomics 4, 1216–1225 (2004).

Li, Z. et al. Profiling tumor-associated antibodies for early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 1, 513–519 (2006).

Daniel, L. A. et al. AZGP1 autoantibody predicts survival and histone deacetylase inhibitors increase expression in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 3, 1236–1244 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by N. Barlev

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, B., Li, X., Ren, T. et al. Autoantibodies as diagnostic biomarkers for lung cancer: A systematic review. Cell Death Discov. 5, 126 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-019-0207-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-019-0207-1

This article is cited by

-

Plasma autoantibodies IgG and IgM to PD1/PDL1 as potential biomarkers and risk factors of lung cancer

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Diagnostic value of circulating genetically abnormal cells to support computed tomography for benign and malignant pulmonary nodules

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

A highly predictive autoantibody-based biomarker panel for prognosis in early-stage NSCLC with potential therapeutic implications

British Journal of Cancer (2022)