Abstract

High-quality clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and consensus statements (CSs) are essential for evidence-based medicine. The purpose of this systematic review was to appraise the quality and reporting of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening CPGs and CSs. After prospective registration (Prospero no: CRD42021286156), a systematic review searched CRC guidances in duplicate without language restrictions in ten databases, 20 society websites, and grey literature from 2018 to 2021. We appraised quality with AGREE II (% of maximum score) and reporting with RIGHT (% of total 35 items) tools. Twenty-four CPGs and 5 CSs were analysed. The median overall quality and reporting were 54.0% (IQR 45.7–75.0) and 42.0% (IQR 31.4–68.6). The applicability had low quality (AGREE II score <50%) in 83% of guidances (24/29). Recommendations and conflict of interest were low-reported (RIGHT score <50%) in 62% guidances (18/29) and 69% (20/29). CPGs that deployed systematic reviews had better quality and reporting than CSs (AGREE: 68.5% vs. 35.5%; p = 0.001; RIGHT: 74.6% vs. 41.4%; p = 0.001). In summary, CRC screening CPGs and CSs achieved low quality and reporting. It is necessary a revision and an improvement of the current guidances. Their development should apply a robust methodology using proper guideline development tools to obtain high-quality evidence-based documents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly worldwide cancer in both men and women, with 1.9 million new cases and a mortality of 10%, 935,000 patients, per year [1]. Early detection of CRC due to screening programmes, removal of precancerous polyps with colonoscopy and advances in treatment management have decreased CRC incidence and mortality rates [2, 3]. It has been demonstrated that early diagnosis could decrease CRC morbimortality. The 5-year mortality rate of 10% for early-stage increases to 28% for locally advanced disease and 86% for metastatic cancer, according to USA data [4].

Although cancer prevention programmes are undoubtedly important, there is a certain variation in CRC screening guidance documents depending on the source [5]. Screening programmes should be accommodated to risk groups to offer strategies adapted to their risk of developing CRC [6]. Patients and clinicians should assess the patient’s overall health, previous screening history, and preferences to define if screening is appropriate [7]. The years range for CRC screening in the general population should be determined to capture the most significant number of CRC cases while considering the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening tests, regional epidemiology, and expected benefits and harms to the screened population. This implies that CRC screening guidelines show heterogeneity in recommendations and purpose since they are often aimed at particular subgroups. This heterogeneity could be a barrier to standardising care quality and make it hard to follow recommendations [8, 9].

Clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and consensus statements (CS) are evidence-based documents to support high-quality care in specific situations [10,11,12,13]. The analysis of the quality (the validity of the recommendations made) and reporting (the rigour of the presentation of the document) are elements that allow practitioners to identify trustworthy guidance documents [14]. Therefore, there is a need to assess recently published CRC screening CPGs and CSs [15]. A decade previously, Simone et al. [16] inspected the quality of CRC guidance documents but with an older tool (AGREE, previous version). Therefore, this review is currently outdated. It focused on hereditary CRC guidance in general (screening, surveillance, and management). That old systematic review [16] only included 17 guidances. Tian et al. [17] published a recent systematic review written in Chinese with only 19 guidances selected and selecting only English and Chinese guidances. There is a need for a broad systematic review focused on CRC screening CPGs and CSs without language or data source limitations. So, given this background, we systematically assessed quality and reporting of all the CRC screening guidances published using current, validated instruments and highlighted each guidance’s strengths and limitations.

Materials and methods

We conducted a thorough systematic review following prospective registration (Prospero ID: CRD42021286156) and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [18,19,20] (Appendix S0).

Literature search strategy, data sources, study selection and data extraction

We completed an exhaustive literature examination of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, CDSR and Tripdatabase from January 2018 to November 2021 without language limitations. Our selection criteria for the time period targeted documents published in the last 3 years (from 2018 onwards), following the advice of an extensive systematic review of the methodological handbooks for updating clinical practice guidelines. This systematic review stated that most handbooks that collect recommendations on updating guidances recommended that they should be updated 3-yearly [21]. We used MeSH terms “practice guidelines”, “guidelines”, “consensus”, “colorectal neoplasms”, “colorectal cancer”, “screening”, “quality”, “reporting” and including term variants. The contribution to global colorectal cancer’s scientific production of the professional societies´ country of origin greater than 0.5% was the main criterion for including these professional societies in our systematic review. Scopus was searched on March 10th, 2022, to estimate the scientific production of each country (85932 “Colorectal Cancer and Health” documents). This decision was in line with the previous peer-reviewed published systematic reviews [22,23,24,25]. We visited 20 pertinent professional organisations´ websites and four guideline databases: National Comprehensive Cancer Network- NCCN, TRIP database, CMA Infobase, Health Services Technology Assessment Texts-HSTAT, and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network-SIGN) to conclude the examination. More additional records were searched in the identified publications´ bibliographies to include other essential studies in our review. Appendix S1 shows the search strategy.

The inclusion criteria were CPGs, CSs, recommendations, and position statements about CRC screening produced by professional organisations, societies, or government agencies. Exclusion criteria were CPGs and CSs not related to CRC screening and protocols in general. We decided to exclude protocols, programmes that sets out a precise sequence of activities in managing a specific clinical condition, as they did not define how a procedure was executed but why, where, when and by whom the care was given [26]. We also rejected obsolete versions of guidelines updated in more recent years from the same organisation, guidelines for education purposes or only for patients. Three independent reviewers (AIA, CMFV and CREL) confirmed eligibility by checking the titles and abstracts and performed a full-text assessment of the selected studies. Duplicate documents were removed. Disagreements or inconsistencies were resolved by consensus with the input of a fourth reviewer (MMC). Data extraction was carried out independently by three authors (AIA, CMFV and CREL) and collected on an Excel datasheet to compare results.

Quality and reporting appraisal

AGREE II statement and RIGHT instrument were used in a manner similar to our previously published work [22, 23] to evaluate quality and reporting, respectively (Appendix S2) [27, 28]. Before data extraction, the reviewers had sessions to understand AGREE and RIGHT criteria (items and domains). After independent data extraction, two reviewers (AIA and CREL) discussed their disagreements, and in case of inability to resolve disagreements mutually, an arbitrator (MMC) helped reach a final judgement.

AGREE II examined the elements of the guideline development and the recommendation grades. It defined quality as the “trustworthiness that conceivable development biases have been properly managed and recommendations are internally and externally valid” [29]. Twenty-three items were categorised into six domains: scope and purpose (items 1 to 3), stakeholder involvement (items 4 to 6), the rigour of development (items 7 to 14), clarity and presentation (items 15 to 17), applicability (items 18 to 21) and editorial independence (items 22 and 23). Each item scored between 1 (strongly disagree, i.e., when there was no information of the item) and 7 (strongly agree, i.e. when there was a well-constructed description). An arbitrator (MMC) solved disparities between the two analysts (AIA and CREL). The global reviewers´ scores were used to calculate the 0–100% domain quality scores following the AGREE II formula supplied in the tool manual [29]. The overall assessment items were also incorporated: a rating of the overall quality of the guidance and an assessment of whether it will be recommended for use in practice. The overall guideline assessment was gauged as the mean scores of the 6 standardised domains, and a recommendation was made: a CPG or CS was “recommended” when scored >80% [30], “recommended with modifications” if scored 50–80%, and “not recommended” if <49% [31].

RIGHT [28] investigated the reporting of the CPGs and CSs, and categorised it into twenty-two items (thirty-five subitems)that were scored as 1 (reported), 0.5 (partially reported), or 0 (unreported) and were categorised into 7 domains: basic information (items 1 to 4), background (items 5 to 9), evidence (items 10 to 12), recommendations (items 13 to 15), review and quality assurance (items 16 and 17), funding and declaration and management of interests (items 18 and 19), and other information (items 20 to 22). An overall reporting appraisal was counted based on the rate of the total (score >80%: “well-reported”, score = 50–80%: “moderate-reported” and score <50%: “low-reported”).

Statistical analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis concerning particular items, domains, and overall scores, expressing the AGREE II and RIGHT scores as a percentage of the maximum possible score. The consistency between “reviewers” was estimated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and it was considered excellent when ICC > 0.90 [32]. AGREE II and RIGHT correlation (“r”) was estimated to analyse if quality and reporting of the guidances were associated. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare guidances outcomes (AGREE II and RIGHT scores). We used Stata 16 for analysis. Statistical significance was p < 0.05.

Results

Study selection

A total of 8199 guidances were found from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, CDSR and Tripdatabase, and 30 documents from the grey literature (guideline specific databases, professional societies, and the Word Wide Web). After removing 439 duplicated guidances, 7752 were also rejected for not fulfilling the inclusion characteristics required (unsuited population or publication, outdated guidances substituted by an update or inappropriate development group). Thirty-eight of the records were filtered for reviewing titles and abstracts. Finally, 29 documents were included (24 CPGs [7, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] and 5 CSs [57,58,59,60,61]) in quality and reporting full-text assessment. Nine documents were excluded for not accomplishing the criteria (4 conference abstracts, 3 posters, and 2 CPG for education and information purposes only). Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study. Table 1 shows the selected studies and their characteristics.

Characteristics of the studies

Table 1 revealed the main characteristics of the chosen manuscripts, including the title, year, country, the supported entity for publication, version, evidence analysis, referral of a quality or reporting tool, type of cancer-focused and months passed after the last update was released. The majority of the guidelines were from North America (69%; 20). Five were from Europe (17%), two from Asia (7%) and one from South America and Oceania (3%) (see Appendix S3). The ICC was 0.85 for quality and 0.82 for reporting.

Quality assessment

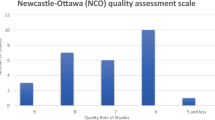

The correlation score between AGREE II and RIGHT in the studies was r = 0.97 (Appendix S4). Quality was very heterogeneous, with a median overall rate of 69.0% (IQR 45.7–75.0; range 23.0%-88.0%). Figure 2 and Appendix S5 compiled the results. Almost 50% (13/29; 45%) of the guides were ranked as “recommended with modifications”, 38% (11/29) as “not recommended”, and only 17% (5/29) as “recommended”. Figure 3 illustrates the accomplishment regarding domains. Scope and purpose (domain 1) and clarity of presentation (domain 4) obtained the best quality with 62% (18/29) of the guidances with high quality (scoring >75%), respectively. Average scores (scoring 50–75%) were obtained in stakeholder involvement (domain 2) with 34% (10/29), the rigour of development (domain 3) with also 34% (10/29), and editorial independence (domain 6) with 28% (8/29). Utterly, only domain 5 (applicability) achieved “low” (25–50%) or “very low” (<25%) with 83% (24/29) in these categories. The guidances with more satisfactory quality were five (in order of high to low quality): the ASCO [56], the Spanish [46], the Banff consensus [58], the ACS [54] and the MAGIC [39] CRC guidelines (Appendix S6).

Reporting assessment

The median overall reporting was 42.0% (IQR 31.4–68.6; range 8.0%–86.0%). Twelve guidances (41.4%) were “recommended with modifications” (scoring >50–80%) while 48.3% (14/29) were “not recommended” (scoring <51%). Only 10.3% (3/29) were “recommended” (scoring >79%). Figure 3 demonstrated the reporting of each domain in the guidances. Basic information (domain 1) was well-reported in 19/29 (66%) of the guidances. Background (domain 2) and review and quality assurance (domain 5) were moderate-reported with 59% (17/29) and 69% (20/29), respectively. The reporting of recommendations (domain 4), funding and declaration and management of interests (domain 6) and other information (domain 7) was scarce with 62% (18/29), 83% (24/29) and 69% (20/29), respectively. The domain median for reporting was 83% (0–100%) in domain 1 (basic information), 63% (0-100%) in domain 2 (background), 40% (0–100%) in domain 3 (evidence), 43% (0–100%) in domain 4 (recommendations), 0% (0–100%) in domain 5 (review and quality assurance), 25% (0–100%) in domain 6 (funding and declaration and management of interests) and finally, 33% (0–100%) in domain 7 (other information). The better reported guidances were the ASCO [56], the Banff consensus [58] and the ACS [54] guidances. Figure 4 and Appendixes S7 and S8 collect this information.

Focus of the guidances

Regarding the focus of the guidance, 18/29 (62.1%) were CPGs and CSs about general CRC screening, 2/29 (6.9%) were focused on average-risk CRC, and 1/29 (3.5%) was about inflammatory bowel disease, and another (3.5%) focused on black men population. Finally, 7/29 (24.1%) were about different sorts of hereditary CRC screening (2/29 (6.9%) for Adenomatous syndrome, 1/29 (3.5%) for Lynch syndrome, and another (3.5%) about CRC related to cyst fibrosis, and finally, 3/29 (10.4%) about general hereditary cancer).

Concerning quality, CRC screening guidances focused on hereditary cancer, and the average-risk population had a better score in all the domains than guidances about general colorectal screening. Scope and purpose domain was 94% in hereditary CRC screening guidances while 77% in general guidances, stakeholder involvement was 75% vs. 55%, the rigour of development was 70% vs. 40%, clarity of presentation 87% vs. 80%, and editorial independence 62% vs. 45%. Only the applicability domain reached a 30% overall score in both general and hereditary guidances. Appendix S9 and S10 show the differences in quality domains depending on the type of guidance (general CRC screening, average-risk CRC screening, hereditary CRC screening, inflammatory bowel disease and specific subpopulations CRC screening guidances).

Concerning Reporting, CPGs and CSs related to hereditary CRC had a better reporting than general guidances in domains 1 to 5 (basic information 88% vs. 72%, background 77% vs. 54%, evidence 80% vs. 42%, recommendations 57% vs. 44%, and review and assurance 42% vs. 25%). But worse in domain 6 funding and conflict of interest (21% vs. 31%) and domain 7 other information (38% vs. 46%). Appendix S11 and Appendix S12 show the reporting depending on the type of guidance.

Factors associated with quality and reporting

The guidances underpinned by systematic reviews obtained better quality (68.5% vs. 35.5%; p = 0.001) and reporting than consensus (41.4% vs. 74.6%; p = 0.001). No significant differences were found between CSs and CPGs (AGREE II: p = 0.729; RIGHT: p = 0.954). The origin (AGREE II: p = 0.181; RIGHT: p = 0.162)., the publication in a journal (AGREE II: p = 0.093; RIGHT: p = 0.063)., the year of publication (AGREE II: p = 0.751; RIGHT: p = 0.852)., the version of the guidance (AGREE II: p = 0.427; RIGHT: p = 0.394), the type of cancer (AGREE II: p = 0.114; RIGHT: p = 0.077) or the referral of a quality tool such as AGREE II or RIGHT (AGREE II: p = 0.189; RIGHT: p = 0.189) did not influence quality or reporting. Quality and reporting of the guideline documents stratified by different characteristics were collected in Table 2.

Discussion

Main findings

This extensive systematic review of CRC screening guidance documents demonstrated a wide variety in quality and reporting. We studied guidances from different countries (5 continents and 8 countries) and languages, which provided an international viewpoint of the present position of screening guidelines for CRC. Analysing quality by AGREE II, almost half of the guides had a moderate quality and needed improvement, and more than a third were classified as not recommended. Concerning reporting examined by RIGHT, most of the guidances had a well-detailed scope and purpose and good clarity of presentation, although applicability was poorly explained. The domains stakeholder involvement, rigour of development and editorial independence were average. More than a third of the guidances were moderate-reported (RIGHT score 50–80%), and almost a third were low-reported (RIGHT score <50%). Basic information was well-reported (RIGHT score >80%); background and review and quality assurance were moderate-reported (RIGHT score 50–80%); the funding reporting, the conflict of interest and other information were low-reported (RIGHT score <50%). The use of systematic reviews was associated with improving quality and reporting of the guidances. No other factors such as the type of guidance (CPGs vs. CSs), the origin, the year of release, the version or the publication in a journal showed a relationship with quality or reporting.

Strengths and limitations

Our study was a broad systematic review focused on CRC screening with no specific languages and no data source limitations to offer an international perspective of the current situation of screening guidelines for CRC. English and Spanish were the most internationally spoken languages [62], and most organisations offered versions in both languages. Our reviewers were native speakers of both English and Spanish. The diversity of the guidances reviewed is an example of the existing heterogeneity of the publications, and it could be unavoidable as guidances varied in their configuration, background, development, objectives, outputs, regional/local epidemiological situation, etc. [63]. The aim of our systematic review was to analyse quality and reporting of CRC screening guidances in general. The external validity of our systematic review, i.e., the extent to which the study’s findings can be generalised, was not affected by the individual validity of the guidances analysed, and our findings could be reproduced.

Our systematic review included CPGs and CSs about CRC screening, although protocols were excluded as they did not accomplish the selection criteria. We must emphasise that some of these countries do have protocols for CRC screening, but they do not provide guidance or recommendations about CRC screening.

For a better understanding of the quality and reporting analysis of the guidances, we decided to classify the CPGs and CSs by their main purpose (general CRC screening, average-risk CRC, inflammatory bowel disease, specific populations, and hereditary cancer), giving the reader a better perspective of the current situation in every type of guidances.

We studied articles published from 2018 onwards. So, we are aware that CPGs and CSs outside our period of time scope from reputable institutions would have been excluded. Our decision to select a 3 years frame was not arbitrary but evidence-based. An extensive systematic review of literature remarked that most guidance methodological handbooks for updating CPGs recommended a two or 3-year window between updates. We are aware that the update of guidances depends on new improvements available. However, regarding evidence [21], the need for a more extensive analysis would be unnecessary since older guidelines would possibly be now obsolete due to quick advances in CRC and anal cancer.

Although the subjective character of the data extraction could introduce bias, CPGs and CSs were assessed by at least two reviewers and an arbitrator in case of disagreements, as AGREE II and RIGHT have recommended in their user manuals [22, 23], increasing the trustworthiness of the data reported. Before using the tools, the reviewers had sessions to learn and unify standards about the process of using AGREE II and RIGHT. The reviewer´s concordance was excellent (ICC > 90%). The reviewers were experienced in systematic reviews, quality health care management [24, 64,65,66], the analysis of guidances and the use of AGREE and RIGHT [22, 23]. They were also experts in the study of CRC and screening (experienced CRC surgeons or specialists related), so they had the relevant vocabulary to understand the documents included properly.

The two validated appraisal instruments used, AGREE II [27] and RIGHT [28], did not guide thresholds or weighting for scoring items and domains. Their instructions suggested avoiding calculating an overall rate for the guidances as it could hide weaknesses in individual domains. We used previously published cut-offs [23, 30, 31] as this approach helps to simplify the analyses. Like other tools, AGREE II and RIGHT have intrinsic boundaries as they do not estimate the strength of recommendations or patient values and choices. We are aware that the interpretation of the results must be handled with caution because, although the guidelines may have similar overall scores, they may differ individually in each domain. This is so because all the domains had the same weight.

Implications

Guidance documents should supply specific evidence-based advice in high-quality care management. The quality of guidelines is an essential condition in its development [67]. However, the attainment of this requirement does not necessarily convey into implementation, and strict compliance with guidance recommendations (even of the more outstanding quality) does not automatically deliver the most proper care per patient [6]. Nowadays, there is a multiplicity of recommendations in CRC screening guidelines [5]. Screening programmes should be adjusted to risk groups to deliver techniques individualised to their risk of acquiring CRC [68]. Clinicians should inspect the patient’s general health, earlier screening history, and choices and values to offer if screening is appropriate [7]. These diverse subgroups with specific necessities would explain the vast heterogeneity of CRC screening guidances recommendations as they differ in aims and implicated subgroups.

High-quality guidance documents are crucial for adequately managing patients. Our systematic review highlighted that quality and reporting of the CRC screening guidance documents had a vast scope for improvements. The debate about weighting and cut-offs of items and domains should be also investigated in the future. Quality was exceptionally poor in the applicability (the description of facilitators and barriers for application, the resources provided for application and the monitoring and auditing criteria) domain, which would merit urgent consideration. The stakeholder involvement, the rigour of development (particularly the external review of the document and an updating procedure) and the editorial independence of the analysed guidances should also enhance their quality (Appendix S13). The formulation of the recommendations was not well-described, and the methodology was not clarified in the majority of the guidances. Primary users of the guideline or the population subgroups were not appropriately reported, and the selection of the guidelines contributors and their roles were not specified. The values and preferences of the target population were not considered in the formulation of each recommendation. CPGs and CSs also did not describe any limitations in their development process nor indicated how any limitations might have affected the validity of the proposals. Guidances did not register any gaps in the evidence or provide future research suggestions. The funding and conflict of interest reporting were very low-reported (see Appendix S14). Guidances that followed systematic review for evidence analysis had obtained better quality and reporting. This finding supported the idea that Systematic reviews are considered the gold standard for evidence-based research [69]. Although CPGs are normally better than CSs [70] in the literature, differences between CPGs and CSs quality and reporting were not significant in our systematic review. This is probably due to the fact that the terms CPGs and CSs are often used interchangeably.

Comparing previous systematic reviews about CRC screening guidances, our results highlighted worse quality in all the areas. Only stakeholder involvement has remained similar in recent guidances to 10 years ago. This could be produced by a selection bias. Former studies had probably selected well-known guidances while our study was more recent and no language restricted; hence, we have analysed a third more guidances than these other studies. Appendix S15 shows the characteristics of the studies and a comparison of domains.

Comparing CRC and breast cancer screening CPGs and CSs (prior publication by our team) [22], CRC guidances had better quality but worse reporting. The applicability was worst in CRC guidelines, but both types of cancer should improve. The scope and purpose, the stakeholder involvement, the rigour of development, the clarity of presentation, and the editorial independence enclosed better quality in CRC guidances. The reporting was more varied. Although basic information, funding, declaration, and management of interests were better documented in CRC guidances, the evidence, the reporting of recommendations, and the review and quality assurance had more valuable reporting on breast cancer CPGs and CSs.

Conclusions

CRC screening guidances had a heterogeneous quality and reporting. Half of the analysed CPGs and CSs had an average quality but low reporting that would merit urgent improvement in all their areas. In the future, the development of guidelines should involve a robust process using appropriate guideline development tools at the start of the process to ensure the production of high-quality guidance based on the best available evidence.

Data availability

The data supporting the results are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Materials availability

The materials supporting the results are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.

Cotton S, Sharp L, Little J. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence and prospects for the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Crit Rev Oncog. 1996;7:293–342.

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96.

Cancer.Net. Colorectal cancer: statistics. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/colorectal-cancer/statistics 2022.

Chetroiu D, Pop CS, Filip PV, Beuran M. How and why do we screen for colorectal cancer? J Med Life. 2021;14:462–7.

Navarro M, Nicolas A, Ferrandez A, Lanas A. Colorectal cancer population screening programs worldwide in 2016: an update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3632–42.

Force USPST, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2021;325:1965–77.

Pavlidis N. Towards a convenient way to practice medical oncology. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:ii3–4.

Fervers B, Philip T, Haugh M, Cluzeau F, Browman G. Clinical-practice guidelines in Europe: time for European co-operation for cancer guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:139–40.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines. In: Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1990.

Browman GP, Snider A, Ellis P. Negotiating for change. The healthcare manager as catalyst for evidence-based practice: changing the healthcare environment and sharing experience. Health Pap. 2003;3:10–22.

Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 1993;342:1317–22.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:527–30.

Booth A. Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Syst Rev. 2016;5:74.

Wouters MW, Jansen-Landheer ML, van de Velde CJ. The quality of cancer care initiative in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:S3–S13.

Simone B, De Feo E, Nicolotti N, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Quality evaluation of guidelines on genetic screening, surveillance and management of hereditary colorectal cancer. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:914–20.

Tian JB, Wen Y, Yang ZY, Zheng YD, Wu Z, Li J, et al. [Quality assessment of global colorectal cancer screening guidelines and consensus]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2021;42:248–57.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–30.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–94.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Vernooij RW, Sanabria AJ, Sola I. Guidance for updating clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review of methodological handbooks. Implement Sci. 2014;9:3.

Maes-Carballo M, Mignini L, Martin-Diaz M, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Khan KS. Clinical practice guidelines and consensus for the screening of breast cancer: a systematic appraisal of their quality and reporting. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;31:e13540.

Maes-Carballo M, Mignini L, Martin-Diaz M, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Khan KS. Quality and reporting of clinical guidelines for breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Breast 2020;53:201–11.

Maes-Carballo M, Moreno-Asencio T, Martin-Diaz M, Mignini L, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Khan KS. Shared decision making in breast cancer screening guidelines: a systematic review of their quality and reporting. Eur J Public Health. 2021;31:873–83.

Maes-Carballo M, Munoz-Nunez I, Martin-Diaz M, Mignini L, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Khan KS. Shared decision making in breast cancer treatment guidelines: development of a quality assessment tool and a systematic review. Health Expect. 2020;23:1045–64.

Hewitt-Taylor J, Melling S. Care protocols: rigid rules or useful tools? Paediatr Nurs. 2004;16:38–42.

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Consortium ANS. The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;352:i1152.

Chen Y, Yang K, Marusic A, Qaseem A, Meerpohl JJ, Flottorp S, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:128–32.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med. 2010;51:421–4.

Oh MK, Jo H, Lee YK. Improving the reliability of clinical practice guideline appraisals: effects of the Korean AGREE II scoring guide. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:771–5.

Hoffmann-Esser W, Siering U, Neugebauer EAM, Lampert U, Eikermann M. Systematic review of current guideline appraisals performed with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II instrument-a third of AGREE II users apply a cut-off for guideline quality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;95:120–7.

Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–63.

Alberta CC. Cancer Care Alberta. Colorectal cancer screening. Clinical Practice Guideline | Nov 2013 (Revised 2020). https://actt.albertadoctors.org/CPGs/Lists/CPGDocumentList/colorectal-cancer-screening-guideline.pdf. 2020.

Alberta CC. Colorectal cancer screening. Clinical Practice Guideline | Nov 2013 (Revised 2020). 2020.

Clarke WT, Feuerstein JD. Colorectal cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: Practice guidelines and recent developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4148–57.

Cubiella J, Marzo-Castillejo M, Mascort-Roca JJ, Amador-Romero FJ, Bellas-Beceiro B, Clofent-Vilaplana J, et al. Clinical practice guideline. Diagnosis and prevention of colorectal cancer. 2018 Update. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:585–96.

Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal I, Moreno C, Kim DH, Bartel TB, Cash BD, Chang KJ, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria((R)) colorectal cancer screening. J Am Coll Radio. 2018;15:S56–S68.

Gupta N, Kupfer SS, Davis AM. Colorectal cancer screening. JAMA 2019;321:2022–3.

Helsingen LM, Vandvik PO, Jodal HC, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with faecal immunochemical testing, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2019;367:l5515.

Jenkins MA, Ait Ouakrim D, Boussioutas A, Hopper JL, Ee HC, Emery JD, et al. Revised Australian national guidelines for colorectal cancer screening: family history. Med J Aust. 2018;209:455–60.

Kwaan MR, Jones-Webb R. Colorectal cancer screening in black men: recommendations for best practices. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:S95–S102.

Lam TH, Wong KH, Chan KK, Chan MC, Chao DV, Cheung AN, et al. Recommendations on prevention and screening for colorectal cancer in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:521–6.

Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, Desouza B, Dunlop MG, East JE, et al. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut 2020;69:411–44.

Network NCC. NCCN guidelines: colorectal cancer screening Version 2.2021. https://www.nccn.org/. 2021.

Qaseem A, Crandall CJ, Mustafa RA, Hicks LA, Wilt TJ. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic average-risk adults: a guidance statement from the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:643–54.

SemFYC AEdG. Diagnóstico y prevención del cáncer colorrectal. ACTUALIZACIÓN 2018. 2018.

Seppala TT, Latchford A, Negoi I, Sampaio Soares A, Jimenez-Rodriguez R, Sanchez-Guillen L, et al. European guidelines from the EHTG and ESCP for Lynch syndrome: an updated third edition of the Mallorca guidelines based on gene and gender. Br J Surg. 2021;108:484–98.

Shaukat A, Kahi CJ, Burke CA, Rabeneck L, Sauer BG, Rex DK. ACG Clinical guidelines: colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:458–79.

America Cancer Society. Detección temprana, diagnóstico y clasificación por etapas. https://www.cancer.org/es/cancer/cancer-de-pulmon/deteccion-diagnostico-clasificacion-por-etapas.html. 2018.

Uruguay MdSd. Ministerio de Salud de Uruguay. Guía de práctica clínica de tamizaje del cáncer colo-rectal 2018. https://www.paho.org/uru/dmdocuments/Guia%20de%20practica%20clinica%20de%20tamizaje%20del%20cancer%20colo-rectal%202018.pdf. 2018.

Washington KFHPo. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington. Colorectal Cancer Screening Guideline. https://wa.kaiserpermanente.org/static/pdf/public/guidelines/colon.pdf. 2021.

Wilkins T, McMechan D, Talukder A. Colorectal cancer screening and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:658–65.

Wilkinson AN, Lieberman D, Leontiadis GI, Tse F, Barkun AN, Abou-Setta A, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for patients with a family history of colorectal cancer or adenomas. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:784–9.

Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:250–81.

Yang J, Gurudu SR, Koptiuch C, Agrawal D, Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in familial adenomatous polyposis syndromes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:963–82. e2.

Lopes G, Stern MC, Temin S, Sharara AI, Cervantes A, Costas-Chavarri A, et al. Early detection for colorectal cancer: ASCO resource-stratified guideline. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–22.

Basu P, Alhomoud S, Taghavi K, Carvalho AL, Lucas E, Baussano I. Cancer Screening in the coronavirus pandemic era: adjusting to a new situation. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:416–24.

Leddin D, Lieberman DA, Tse F, Barkun AN, Abou-Setta AM, Marshall JK, et al. Clinical practice guideline on screening for colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of nonhereditary colorectal cancer or adenoma: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Banff Consensus. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1325–47. e3.

Hadjiliadis D, Khoruts A, Zauber AG, Hempstead SE, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, et al. Cystic fibrosis colorectal cancer screening consensus recommendations. Gastroenterology 2018;154:736–45. e14.

Hyer W, Cohen S, Attard T, Vila-Miravet V, Pienar C, Auth M, et al. Management of familial adenomatous polyposis in children and adolescents: position paper from the ESPGHAN polyposis working group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:428–41.

中国抗癌协会肿瘤内镜学专业委员会 国上国中医中中消中中中金国. 中国早期结直肠癌筛查流程专家共识意见 (2019, 上海) . Natl Med J China. 2019;99.

Amano T, Gonzalez-Varo JP, Sutherland WJ. Languages are still a major barrier to global science. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e2000933.

Pentheroudakis G, Stahel R, Hansen H, Pavlidis N. Heterogeneity in cancer guidelines: should we eradicate or tolerate? Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2067–78.

Maes-Carballo M, Gomez-Fandino Y, Reinoso-Hermida A, Estrada-Lopez CR, Martin-Diaz M, Khan KS, et al. Quality indicators for breast cancer care: a systematic review. Breast 2021;59:221–31.

Maes-Carballo M, Munoz-Nunez I, Martin-Diaz M, Mignini L, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Khan KS. Shared decision making in breast cancer treatment guidelines: development of a quality assessment tool and a systematic review. Health Expect. 2020;23:1045–64.

Maes-Carballo M, Gomez-Fandino Y, Estrada-Lopez CR, Reinoso-Hermida A, Khan KS, Martin-Diaz M, et al. Breast cancer care quality indicators in Spain: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6411.

Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:385–92.

Hoffmann S, Crispin A, Lindoerfer D, Sroczynski G, Siebert U, Mansmann U, et al. Evaluating the effects of a risk-adapted screening program for familial colorectal cancer in individuals between 25 and 50 years of age: study protocol for the prospective population-based intervention study FARKOR. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:131.

Pussegoda K, Turner L, Garritty C, Mayhew A, Skidmore B, Stevens A, et al. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst Rev. 2017;6:131.

Jacobs C, Graham ID, Makarski J, Chasse M, Fergusson D, Hutton B, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements in oncology-an assessment of their methodological quality. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e110469.

Acknowledgements

KSK is a Distinguished Investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senior modality) Programme grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Spanish Government.

Funding

This systematic review was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMC conceived the work. MMC, AIA, CREL and CMFV compiled and analysed the data for the systematic review. MMC and ABC interpreted the data. MMC wrote the first version of the draft. KSK, ABC, MMD and MGG edited the work critically for important academic content. ABC and KSJ directed the work. All authors consented to the final version of the manuscript. They agreed to be responsible for all elements of the review, providing those questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and solved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Maes-Carballo, M., García-García, M., Martín-Díaz, M. et al. A comprehensive systematic review of colorectal cancer screening clinical practices guidelines and consensus statements. Br J Cancer 128, 946–957 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-02070-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-02070-4

This article is cited by

-

Clinical practice guidelines for the nutrition of colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review

Supportive Care in Cancer (2024)

-

Esophagogastroscopic Abnormalities Potentially Guided Patients Younger than 50 Years Old to Undergo Colonoscopy Earlier: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2024)