Abstract

Introduction Many patients present to doctors with oral health conditions and it is, therefore, important that they have the knowledge and skills to give advice and signpost appropriately.

Aim To ascertain the baseline knowledge and confidence of doctors in managing oral conditions and to identify topic areas for training.

Design A baseline survey was conducted. Two training programmes were then delivered based on the finding of this survey, followed by a post-training survey.

Setting North West London training programme for foundation year 1 (FY1) doctors and general medical practitioner (GP) trainees.

Intervention The FY1 doctors had a didactic teaching session. The GP trainees had a training session combined with foundation dentists (FDs), comprised of a lecture and small, mixed group work.

Main outcomes measured i) post-training confidence in managing oral conditions, answering patients' questions regarding oral health and signposting patients; ii) the most useful and relevant topics of the training for their daily practice.

Results The majority of the doctors had previously received no oral health teaching. Furthermore, the majority did not feel confident at managing oral conditions or signposting patients appropriately. Common topic areas were identified where doctors wanted more oral health teaching.

Conclusions FY1 and GP trainees lack knowledge and confidence with regard to the management of oral health issues and recognise that there is a need to know about oral health. This work highlights the need for structured training to equip doctors with appropriate oral health knowledge and skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Presents the baseline oral health knowledge of doctors and their confidence in managing oral health-related conditions and giving advice to patients.

-

Presents the results of two training programmes aimed at improving their knowledge and confidence.

-

Discusses the key oral health topic areas that doctors found most relevant to their daily practice.

Introduction

Many patients present to GPs and accident and emergency departments (A&E) with oral conditions.1,2,3 It has been estimated that there are 600,000 consultations with GPs for oral problems each year in England, costing an estimated £26.4 million, and 135,000 patients presenting to A&E.1,2 Possible reasons for this include the perceived lack of access to dental services, patient costs associated with dental care compared to free general health care, fear among some patients of attending the dentist, and a perception that dentists only manage tooth problems rather than other oral pathology.4,5,6

There is, therefore, a need for doctors to know how to diagnose and manage oral conditions, and to be aware of how to refer or signpost to local dental services. Many systemic diseases have oral manifestations and an ability to recognise these will help with general medical diagnosis.7 Additionally, some medical interventions require an oral assessment before commencement and consequently doctors need to be aware of the indications for this and how to refer for such.8 Inpatients need to be provided with good oral care and it is crucial that doctors recognise the importance of maintaining good oral health during their hospital stay, as this may impact on general health outcomes such as the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.9 Furthermore, it is important that all health professionals are giving consistent evidence-based preventative advice to patients.10 Doctors can play a key role in improving the population's oral health and can 'make every contact count' by giving brief dental advice, especially to patients who do not regularly attend a dentist.11

Despite this, research suggests that there is limited knowledge among junior doctors working in emergency medicine of how to diagnose oral disease.12 There is also low confidence in conducting oral examinations and diagnosing oral cancer among doctors.13,14,15 Lack of training has been identified as a key barrier to examining the oral cavity and diagnosing oral conditions.12,13,14,15 A majority of doctors report receiving no training in oral health.16,17,18 Many medical schools include no oral pathology teaching in their curriculum and when teaching is provided, there is wide variation in the time dedicated and methods used.12,19 The majority of GP training programmes also provide no oral health training and very few GP trainees undertake hospital posts with any oral disease experience.20 Doctors report prescribing antibiotics for oral issues.21,22 This raises questions of the appropriateness of this given their reported lack of oral health training and concerns about antimicrobial resistance.

There is a need to identify what oral health topics doctors frequently encounter in their clinical practice and what advice is commonly sought from them by patients. There is also a need to ascertain doctors' current knowledge of oral health and identify specific areas where doctors feel they would like more training. This will allow for the development of targeted training to enhance their ability to manage oral conditions and appropriately refer patients.

This paper presents the findings of a survey designed to identify these topic areas and doctors' baseline knowledge and confidence in managing oral health-related issues. It will also evaluate two teaching sessions which were designed based on these findings.

Methods

Participants

Two groups of doctors were included: 24 foundation year 1 (FY1) doctors and 30 GP trainees. The participants were on London Health Education England structured training programmes, into which oral health teaching was incorporated. GP trainees were working primarily in general practice (primary care), where many patients with oral health problems present. Many FY1 doctors were spending time in primary care practices and emergency departments, where oral health disease is most likely to present.

Pre-training survey

A survey was designed by the authors to ascertain the doctors' baseline knowledge of oral health and confidence in managing oral conditions. All survey responses were anonymous. The survey was distributed to the GP trainee participants in person during their regular teaching sessions and then collected one week later. The FY1 participants completed the survey immediately prior to their oral health training session.

The survey included:

-

1.

Multiple choice questions about oral health

-

2.

Questions about the quantity of oral health teaching they had as an undergraduate and postgraduate

-

3.

Questions asking them to self-score their confidence in managing oral conditions, answering patients' questions about oral health and signposting patients with oral problems to local services

-

4.

Past experiences they have had with patients suffering from oral health-related conditions and what questions patients have asked them relating to oral health

-

5.

What they wanted to know about oral health and dental services.

Training sessions

Two different training packages were then designed for the FY1 doctors and GP trainees. The content of the teaching sessions was guided by the results of the questionnaire.

The FY1 doctors had a one-hour didactic teaching session, with an opportunity for follow up questions.

The presentation included the following topics:

-

1.

An overview of the structure of oral health provision

-

2.

Oral epidemiology, locally and nationally

-

3.

An explanation of common oral disease

-

4.

Key evidence-based messages to prevent oral disease

-

5.

How to manage patients with acute oral problems

-

6.

Medical interventions requiring pre-dental screening

-

7.

An overview of oral medicine and oral cancer.

The GP trainees had a half day training session, which was combined with foundation dentists (FDs). The two professional groups were brought together to share experiences and learn from each other. This session began with a didactic lecture including common areas of overlap between dentistry and medicine. The participants were then split into smaller, mixed groups to discuss cases including dental trauma management, oral disease prevention guidelines, acute oral problem management, access to local dental services and common dental questions patients may ask GPs. Peer-to-peer inter-professional learning was used, as participants discussed their personal experiences and taught each other about their field of expertise.

Post-training survey

A post-training questionnaire was completed after the teaching sessions. This asked them to self-score their confidence following the training, record how useful and relevant to their daily practice the teaching had been, what the most useful learning points were, and suggestions for future improvements.

Results

Participants

Thirty GP trainees and 24 FDs attended the inter-professional learning session. Twenty-four FY1s attended the didactic teaching session. Nineteen GP trainees completed the pre-training questionnaire and 22 GP trainees completed the post-training evaluation questionnaire. Twenty-four FY1s completed both the pre- and post-training questionnaire. A breakdown of previous oral health training received is presented in Table 1.

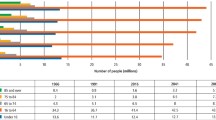

Confidence rating pre- and post-training

The confidence levels of FY1s and GP trainees, both before and after oral health training, is set out in the following tables (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

The percentage of respondents answering correctly to the multiple choice questions is shown in Table 5.

Previous clinical experience and self-identified knowledge gaps

Common oral health topic areas that patients had asked doctors were identified. These included wisdom tooth problems, treatment for dental pain and abscesses, dental caries, bleeding gums, oral hygiene issues, trauma and halitosis. Doctors wanted to know about local dental services and how to access them, which patients they should refer, what are we expected to do before referring and how to refer. They also wanted to know where the nearest emergency services are for dentistry. They felt they needed to know more about who was entitled to NHS dentistry and who to contact if patients have dental problems.

In terms of oral health, doctors felt they needed to know more about common oral conditions that could be managed by them and the basics they could do to help. They wanted more knowledge about the common causes of dental pain and managing dental emergencies and when to prescribe antibiotics. They wanted the skills to be able to assess teeth and to know what advice to give patients about oral health.

Key areas participants learnt about in training that were most relevant to their daily practice

The most significant areas of learning, which proved to be most relevant to the daily practice of FY1s and GP trainees, are presented in Table 6.

Feedback for the teaching session

The majority of participants rated both sessions as very good and all participants found the session relevant or very relevant to their daily practice:

'Very useful session about a topic we didn't even realise we were ignorant about.'

'Super useful, didn't even realise I knew nothing about this topic. Very useful for A&E and GP jobs.'

Discussion

The majority of the doctors had received no teaching on oral health during either their undergraduate or postgraduate training programmes. Those that did have training, usually only had one to two hours of didactic teaching at undergraduate level and this was not consolidated as a postgraduate. There is a clear gap within medical education for oral health training at both an undergraduate and postgraduate level. These findings support other studies which have also found that doctors received no, or limited, oral health training.16,17,18

The majority of doctors did not feel confident at examining the teeth and mouth, managing oral condition, answering patients' questions about oral health or signposting patients to appropriate dental services before the training. Again, this supports the findings of previous studies showing low confidence among doctors in oral examination.12,13,14,15 GP trainees were more confident in each of these areas compared to FY1s, as would be expected due to their increased clinical experience and medical training. Post-training confidence increased in all of these areas for both the FY1s and the GP trainees and the majority were moderately confident after the training. It is hoped that this training would provide the foundation in knowledge and skills to manage oral conditions but further practical encounters and experience would be needed to have greater confidence in managing oral conditions.

It is encouraging that the majority of the doctors knew that NHS dental services are free for children and teeth should be brushed as soon as they erupt. However, they did have limited knowledge regarding dental trauma and this could have a significant impact on the long-term prognosis of a traumatised tooth. Some doctors also responded that antibiotics are indicated for dental pain, which supports previous studies that have raised the issue of doctors prescribing for oral health issues not in line with current guidance.21,22 It was also concerning that the majority of the doctors thought children should first attend the dentist at a much later age then is recommended by the dental profession, with some responding that they should first attend at age five. This is a key challenge to ensure that all health professionals are giving appropriate advice and promoting early dental attendance to patients and their families. Early attendance allows evidence-based preventive advice to be given before oral disease has occurred and is a key area for change, as encouraged by the 'Dental Check by One' (DCby1) initiative23 and the current NHS England initiative of 'Starting Well'.24 Over half of doctors also responded incorrectly that patients should rinse out with water after brushing.

When asked what topic areas the teaching should focus on, there were several areas that were frequently mentioned. These included information about local dental services and how to refer to them, especially for urgent dental care. Doctors wanted some basic knowledge of how to examine the mouth, what a normal mouth looks like and an explanation of common oral conditions. They also wanted to know what evidenced-based preventative advice they should be giving to patients to maintain good oral health. A key area of concern was how to manage dental trauma and dental pain, including when to prescribe antibiotics. Answers to basic frequently asked questions by patients were also sought, such as the cause and treatment of bleeding gums, halitosis and ulcers.

Post-training, the doctors reported that the most useful learning areas related to when to refer patients for pre-treatment dental screening; how to manage dental pain, dental abscesses and dental trauma; how the dental system is organised; and to whom and when to refer patients. Oral medicine was a topic frequently highlighted during the pre-training survey. This is a key area of overlap between medical and dental professions. It is an area that some patients may see more as being within a doctor's remit, despite dental professionals having greater training in oral medicine and it being a dental speciality.4 Oral medicine is also part of many systemic diseases and doctors see it as directly relevant to their daily practice.

There was a very positive response and genuine interest from participants. The doctors recognised the relevance of the topic to their daily practice and to them providing holistic patient care. It was apparent that many of them had very limited knowledge of oral health and much of the teaching was uncovering 'unknown unknowns'. There was also a recognition that more needs to be done to build links between dentists and doctors within the local community to provide coordinated patient care. There was enthusiasm for building local networks and contacts, to share knowledge and seek advice between professional groups.

Factors for consideration

This study has some limitations. It was limited to FY1 doctors and GP trainees in one training region. Other training areas may have different teaching arrangements and this may, therefore, not be representative of England as a whole. However, participants had studied for their undergraduate degree at a variety of universities. It was also a small sample size and only incorporated two training grades, so other doctors at different training stages and on different training pathways may have differing levels of oral health knowledge and learning needs. The design of the study allowed for rapid data collection about a broad range of topics but it did rely on self-reported knowledge and confidence. Also, questionnaires were not available for all GP trainees, both before and after the training, due to non-return of the survey.

A clear need for the introduction of a structured oral health education programme for doctors has been identified. They have self-identified limited confidence in managing oral conditions, but show enthusiasm to learn and recognition of its relevance to their practice. It may be that the best time for this education is during the foundation programme, where FY1 doctors have weekly structured teaching sessions. At this point in their training they have had some clinical experience to put the teaching into context and the vast majority will be placed on an emergency department and GP rotations. To ensure universal coverage, a push must be made to get oral health added to the foundation doctor curriculum, to ensure that doctors are all equipped with the knowledge to manage oral conditions and give evidenced-based preventative advice. The curriculum of doctors is already very busy and it may be that more flexible learning options also need to be considered, such as an e-learning package, to ensure the maximum reach of oral health education to the medical profession. This may also help with issues around the lack of access of oral health experts to teach doctors, as many medical schools and foundation programmes have no links to dental hospitals. Other options include utilising the maxillofacial workforce for teaching or linking FDs and FY1s, as in this study, for bidirectional learning.

Conclusion

FY1 doctors and GP trainees have limited knowledge and confidence to manage oral health issues. There is recognition among them of the need to know about oral health issues and a desire to learn more about local dental services, emergency management of dental pain and trauma, and preventative advice to give to patients to enable them to maintain good oral health. Doctors encounter many patients with oral health issues, whether it be patients presenting in pain to emergency departments or primary medical care, patients with poor oral health on their wards or the need for pre-dental screening before certain interventions.1,2,3 It is, therefore, crucial that we ensure that there is structured training in place to equip doctors with the appropriate knowledge and skills.

It is also important that we encourage doctors and dentists within local communities to build links and share knowledge, in order to treat patents in a holistic manner. The value of inter-professional learning and network development needs to be recognised and promoted. In order to continue to improve the population's oral health, the help of all health and social care professionals is needed to disseminate evidenced-based preventative advice and signpost patients to the dentist at an early age.

References

British Dental Association. NHS charges masking cuts and driving patients to GPs, say dentists. 2016. Available at https://bda.org/news-centre/press-releases/nhs-charges-masking-cuts-and-driving-patients-to-gps(accessed February 2019).

British Dental Association. Toothache piling financial pressure on A&E. 2017. Available at https://bda.org/news-centre/press-releases/Pages/Toothache-piling-financial-pressure-on-A-E.aspx (accessed February 2019).

Currie C C, Stone S J, Connolly J, Durham J. Dental pain in the medical emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Oral Rehabil 2017; 44: 105-111.

Bell G W, Smith G L, Rodgers J M, Flynn R W, Malone C H. Patient choice of primary care practitioner for orofacial symptoms. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 669-673.

Hill K B, Chadwick B, Freeman R, O'Sullivan I, Murray J J. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: relationships between dental attendance patterns, oral health behaviour and the current barriers to dental care.Br Dent J 2013; 214: 25-32.

Healthwatch. Evidence review: Access to NHS Dental Services: what people told Healthwatch. 2016. Available at https://www.healthwatch.co.uk/sites/healthwatch.co.uk/files/access_to_nhs_dental_services_-_what_people_told_local_healthwatch_0.pdf(accessed February 2019).

Porter S R, Mercadente V, Fedele S. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Br Dent J 2017; 223: 683-691.

Ryan P, Zarringhalam P, Gibbons A J. Dental evaluation before medical treatment: who to refer?Br J Gen Pract 2015; 65: e58-e60.

Hua F, Xie H, Worthington H V, Furness S, Zhang Q, Li C. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 10: CD008367.

Public Health England. Health matters: child dental health. 2017. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-child-dental-health/health-matters-child-dental-health (accessed February 2019).

Health Education England. Making Every Contact Count (MECC). 2019. Available at https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/ (accessed February 2019).

McCann P J, Sweeney M P, Gibson J, Bagg J. Training in oral disease, diagnosis and treatment for medical students and doctors in the United Kingdom. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 43: 61-64.

Morgan R, Tsang J, Harrington N, Fook L. Survey of hospital doctors' attitudes and knowledge of oral conditions in older patients.Postgrad Med J 2001; 77: 392-394.

Carter L M, Ogden G R. Oral cancer awareness of general medical and general dental practitioners.Br Dent J 2007; 203: E10.

Macpherson L M, McCann M F, Gibson J, Binnie V I, Stephen K W. The role of primary healthcare professionals in oral cancer prevention and detection.Br Dent J 2003; 195: 277-281.

Colgan S M, Randall P G, Porter J D H. 'Bridging the gap' - A survey of medical GPs' awareness of child dental neglect as a marker of potential systemic child neglect.Br Dent J 2018; 224: 717-725.

Kalkani M, Ashley P. The role of paediatricians in oral health of preschool children in the United Kingdom: a national survey of paediatric postgraduate speciality trainees.Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2013; 14: 319-324.

Olive S, Tuthill D, Hingston E J, Chadwick B, Maguire S. Do you see what I see? Identification of child protection concerns by hospital staff and general dental practitioners.Br Dent J 2016; 220: 451-457.

Bater M C, Jones D, Watson M G. A survey of oral and dental disease presenting to general medical practitioners.Qual Prim Care 2005; 13: 139-142.

Ahluwalia A, Crossman T, Smith H. Current training provision and training needs in oral health for UK general practice trainees: survey of General Practitioner Training Programme Directors.BMC Med Educ 2016; 16: 142.

Cope A L, Chestnutt I G, Wood F, Francis N A. Dental consultations in UK general practice and antibiotic prescribing rates: a retrospective cohort study.Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: e329-e336.

Cope A L, Wood F, Francis N A, Chestnutt I G. General practitioners' attitudes towards the management of dental conditions and use of antibiotics in these consultations: a qualitative study.BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008551.

British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Dental Check by One. 2019. Available at https://www.bspd.co.uk/Patients/Dental-Check-by-One(accessed February 2019).

NHS England. Starting Well. 2019. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/dentistry/smile4life/starting-well-13/(accessed February 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grocock, R., Holden, B. & Robertson, C. The missing piece of the body? Oral health knowledge and confidence of doctors. Br Dent J 226, 427–431 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0077-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0077-1