Abstract

Omidubicel (nicotinamide-expanded cord blood) is a potential alternative source for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) when an HLA-identical donor is lacking. A phase I/II trial with standalone omidubicel HCT showed rapid and robust neutrophil and platelet engraftment. In this study, we evaluated the immune reconstitution (IR) of patients receiving omidubicel grafts during the first 6 months post-transplant, as IR is critical for favorable outcomes of the procedure. Data was collected from the omidubicel phase I-II international, multicenter trial. The primary endpoint was the probability of achieving adequate CD4+ T-cell IR (CD4IR: > 50 × 106/L within 100 days). Secondary endpoints were the recovery of T-cells, natural killer (NK)-cells, B-cells, dendritic cells (DC), and monocytes as determined with multicolor flow cytometry. LOESS-regression curves and cumulative incidence plots were used for data description. Thirty-six omidubicel recipients (median 44; 13–63 years) were included, and IR data was available from 28 recipients. Of these patients, 90% achieved adequate CD4IR. Overall, IR was complete and consisted of T-cell, monocyte, DC, and notably fast NK- and B-cell reconstitution, compared to conventional grafts. Our data show that transplantation of adolescent and adult patients with omidubicel results in full and broad IR, which is comparable with IR after HCT with conventional graft sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immune reconstitution (IR) is an important predictor for outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic (stem) cell transplantation (HCT) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. IR can be affected by a variety of factors, such as conditioning regimen and cell source [9, 10]. Common first-choice sources for allogeneic HCT in adults are peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) or bone marrow (BM) from related or unrelated donors. Nevertheless, for many adult patients, no PBSC or BM donor can be found, because of the requirement for high-grade human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matching. The use of umbilical cord blood (CB) provides an alternative cell source in these patients since lower-grade HLA-matching has proven to be acceptable to ensure a low risk of graft failure or graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [11,12,13]. However, in order to ensure timely engraftment, patients must receive an adequate dose of stem cells/kg [14, 15]. This may introduce a problem when using CB as a stem cell source in adults, since CB-grafts generally contain lower amounts of nucleated (stem) cells compared to PBSC/BM, resulting in delayed engraftment. One option to overcome the limited amount of stem cells is transplantation using two CB-grafts (double cord blood transplantation; dUCBT) [16, 17]. However, dUCBT still does not overcome the delayed engraftment and may be associated with an increased risk of GvHD [18,19,20]. Methods to expand CB stem cells provide another option to enhance CB-graft availability for adult patients. One option to expand CB stem cells is a nicotinamide-based protocol: omidubicel (Gamida Cell, Jerusalem, Israel).

Omidubicel is an ex vivo expanded cell product derived from the CD133+ fraction of banked CB that uses an epigenetic strategy to inhibit differentiation and enhances the functionality of cultured hematopoietic stem and -progenitor cells. Nicotinamide is the active agent of this expansion strategy. When nicotinamide is added to stimulatory hematopoietic cytokines, CB-derived hematopoietic progenitor cell cultures demonstrate an increased frequency of phenotypically primitive CD34+ CD38− cells and a substantial increase in BM homing and engraftment potential of ex vivo expanded CD34+ cells [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Omidubicel is comprised of ex vivo expanded stem cell fraction (omidubicel cultured fraction (CF)) and a non-cultured cell fraction of the same CB unit (omidubicel non-cultured fraction (NF)) consisting of mature myeloid and lymphoid cells. A phase I/II trial with standalone omidubicel HCT showed rapid neutrophil (11.5 days) and platelet engraftment (34 days) [23]. This early hematopoietic recovery reflects the ability of nicotinamide to expand both committed and long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and was shown to be associated with a lower risk of bacterial infections and shorter hospitalization in the first 100 days compared with standard unmanipulated CB transplantation (unCBT) [22, 23].

We and others have recently shown that adequate CD4+ T-cell IR (CD4 + IR) is crucial for favorable survival outcomes [1, 2, 6,7,8]. Patients with adequate CD4 + IR (>50 × 106 CD4+ T-cells/L blood, within 100 days after HCT) had a lower risk of viral reactivation [1], virus-related morbidity and mortality [1], aGvHD-related mortality [27], and relapse-related mortality [6, 8]. In addition, IR of other immune cell subsets, such as natural killer (NK)-cells [28,29,30], CD8+ T-cells [31,32,33], and B-cells [34,35,36,37,38,39], were also related to HCT outcome. As a result of the manufacturing process manipulations and freeze-thaw cycles, the CD3+ dose of the omidubicel NF is lower than in a standard CBT. For example, Purtill et al. reported a median infused viable dose 4.27 × 106 CD3+ cells/kg [40]. This is also consistent with the previously published omidubicel experience, indicating that the median CD3+ cell dose from the omidubicel unit was 1.3 × 106 cells/kg, which was significantly lower than the median cell dose from the unmanipulated unit of 3.4 × 106 cells/kg [41]. The omidubicel CF yields hematopoietic stem and myeloid progenitor cells, but lymphoid cells cannot be detected based on cell surface marker analysis. However, the development of lymphoid cell subsets occurs de-novo from the expanded CD34+ stem and progenitor cells post-transplant [21, 23, 24]. The NF contains mature lymphocytes. The lower CD3+ dose in omidubicel may theoretically be postulated to contribute to a risk of impaired immune recovery following transplantation. Nevertheless, detailed information on IR after transplantation with omidubicel has not yet been reported to date.

We performed in-depth immune monitoring and evaluated plasma protein profiles in patients transplanted with omidubicel grafts in a phase I/II international multicenter study. For this, we developed multicolor flow cytometry panels for harmonized measurements to evaluate the recovery of T-, B-, natural killer (NK)-cell, monocyte, and dendritic cell (DC) subsets.

Patients and methods

Patients and treatment

In this phase, I/II multicenter trial, patients with hematologic malignancies received an omidubicel-HCT after myeloablative (MA) conditioning without antithymocyte globulin (ATG), at 11 clinical sites throughout the United States, Europe, and Singapore. Conditioning regimens were applied according to local standard protocols, and are described in a previous publication of this trial [23]. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions and the national regulatory authorities. All patients provided written informed consent. Patients were enrolled, and data were collected and registered prospectively only after written informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines and Good Clinical Practice (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01816230).

Immune monitoring and blood cell samples

Immune monitoring was performed on peripheral blood samples drawn at 7, 14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after infusion of the graft. Absolute leukocyte, lymphocyte, neutrophil, and monocyte cell numbers were measured in fresh EDTA-whole blood. Mononuclear cells were isolated using Fico-II-Paque (BD Biosciences, Sweden) and cryopreserved for later measurements with the use of standardized and validated multicolor flow cytometry panels. The subsets identified were; for T-cells: naïve (CCR7+ CD27+ CD45RO− CD45RA+), central memory (CCR7+ CD27+ CD45RO+ CD45RA−), effector memory (CCR7− CD27− CD45RO+ CD45RA−), Temra (CCR7− CD27− CD45RO− CD45RA+), and Treg (CD4+ CD25+ CD127lowFoxP3+) [42, 43]. The T helper cell phenotypes were based on chemokine receptor expression shown to be associated with Th helper subsets and in this manuscript are referred to as “Th1” (CD4+ CXCR3+ CCR4− CCR6−), “Th2” (CD4+ CCR6− CXCR3− CCR4+), “Th17” (CD4+ CCR6+ CXCR3+ CCR4− CCR10−), “Th22” (CD4+ CCR6+ CXCR3− CCR4+ CCR10+) [42, 43]. B-cells were characterized into immature (CD19+ CD24++ CD38++ IgM+ IgD−), transitional (CD19+ CD24++ CD38++ IgM+ IgD+), follicular (CD19+CD24+CD38+IgM+IgD+), memory (CD19+ CD24− CD38+), and plasmablast (CD19+ CD24− CD28++) [44, 45]. For other subsets, markers were as follows: for NK-cells: naïve (CD3− CD56++ CD16−) and effector (CD3− CD56+ CD16+; for NK T-cells: NKT (CD3+ CD56+)), invariant NKT (iNKT; CD3+ CD56+ TCRVbeta11+ TCRValpha24+) [46, 47]; for monocytes: classical (lin-HLA.DR+ CD14+ CD16−), intermediate (lin-HLA.DR+ CD14+ CD16+), non-classical (lin-HLA.DR+ CD14− CD16+) [48]; and for DCs: conventional (cDC; lin-HLA.DR + CD14-CD16-CD11c + CD123−; available numbers of cells were too low to report DC1 versus DC2) and plasmacytoid (pDC; lin-HLA.DR+ CD14− CD16− CD11c− CD123+) [49, 50]. An overview of the monoclonals used is provided in Supplemental Table 1. Subsets were calculated as the percentage of total evaluable immune cells. Absolute lymphocyte, leukocyte, and monocyte counts were available from standard immune monitoring on fresh material. Absolute numbers of immune cell subsets from in-depth immune monitoring were calculated from total absolute lymphocyte number (for T-, B-, NK-cells) or leukocyte number (for DC).

Luminex and plasma samples

Plasma was collected by centrifuging EDTA-whole blood samples, from the same samples as for immune monitoring on blood cells, at 0, 1, 7, 14, 21, 42, and 70 days after transplantation. A total of 60 plasma proteins were measured per sample using multiplex immunoassays (Luminex Technology); IL1RA, IL2, IL3, IL4, IL5, IL6, IL7, IL10, IL15, IL17, IL18, IL22, TNFα, IFNα, IFNγ, APRIL, OSM, LAG3, Follistatin, I309, MIP1a, MIP1b, IL8, MIG, IP10, BLC, OPG, OPN, G-CSF, M-CSF, GM-CSF, SCF, HGF, EGF, AR, VEGF, CD40L, sPD1, FASL, IL1R1, IL1R2, ST2, TNFR1, TNFR2, sIL2Rα, sCD27, IL7Rα, sSCFR, Elastase, S100A8, Gal9, Ang1, Ang2, LAP, TPO, sICAM, sVCAM, MMP3, Gal3, C5a. The multiplex immunoassay was performed according to the protocol from the MultiPlex Core Facility of the UMCU [51].

Data analysis

The primary endpoint was the probability of achieving CD4 + IR; > 50 × 106 CD3+ CD4+ cells/L blood on two consecutive measurements within 100 days. Secondary endpoints were IR over time of CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ T-cell subsets, monocytes, NK- and B-cell subsets during 0–180 days after HCT. LOESS-regression curves and cumulative incidence plots were used for data description. The relation between plasma protein- and IR data was analyzed using Spearman regression. R software (version 4.0.1) and ggplot2 package (version 3.3.3) were used for data analysis and production of graphs [52].

Results

In this phase I/II multicenter trial, 36 omidubicel recipients (median age 44; range 13–63 years) were included. Patient characteristics are described elsewhere [23]. Omidubicel cell dose consisted of a median 6.3 × 106 CD34+/kg, and 2.4 × 106 CD3+ T-cells/kg of the co-infused negative fraction (following CD133+ selection). Informed consents for in-depth immune monitoring were available from 28 omidubicel recipients. There was no selection bias for these 28 consented patients, based on median age (39 years [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]) and median cell dosages of 6.1 × 106 CD34+/kg and 2.4 × 106 CD3+T-cells/kg.

IR after omidubicel transplantation

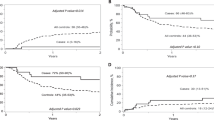

Since early adequate CD4+ IR has been related to lower infection-related morbidity and lower overall mortality [1,2,3, 7, 53], we evaluated CD4+ IR probability in omidubicel recipients. CD4+ IR was evaluable in 20 patients; not all 28 patients had data on absolute CD4+ T cell count on two consecutive time points within the first 100 days after HCT. This was either due to death prior to achieving two data points or limited lymphocyte data available to calculate absolute CD4+ T cell count. Eighteen (90%) achieved successful CD4+ IR (Fig. 1-left). Including all 28 consented patients, adaptive immune cell reconstitution of overall CD4+ (Fig. 1-right), CD8+ (Fig. 2-left), and CD3+ (Fig. 2-right) T-cells, and B-cells (Fig. 3), was observed within the first 6 months after omidubicel transplantation, with a slightly earlier recovery of innate immune cells, including NK-cells (Fig. 4), monocytes (Fig. 5), and DCs (Fig. 6). Especially, the reconstitution of B- and NK-cells was fast compared to other cell subsets, with early high cell counts of ∼500 and ∼1500 × 106 cells/L blood, respectively, within the first month after transplantation.

(Left) Cumulative incidence curve of CD4+IR probability after transplantation with omidubicel transplantation. CD4+ IR was evaluable in 20 patients and was defined as having >50*106 CD4+ T-cells/L in two consecutive measurements within 100 days after transplantation. (Right) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute CD4+ T-cell counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Lower, right) Pie-charts of CD4+ T-cell subsets as percentages; naïve, effector memory (EM), central memory (CM), and EMRA T-cells, at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation.

(Upper) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute CD8+ (left) and total (right) T-cell counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Lower) Pie-charts of CD8+T-cell subsets as percentages; naïve, effector memory (EM), central memory (CM) and EMRA T-cells, and total T-cell subsets as percentages; gamma-delta T-cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation.

(Upper) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute B-cell counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Lower) Pie-charts of B-cell subsets as percentages of B-cells; immature, transitional, follicular, memory B-cells, and plasma cells, at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation.

(Upper) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute NK-cell counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Middle) Pie-charts of NK-cell subsets as percentages of NK-cells; effector and naïve NK-cells, at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation. (Lower) Smoothened LOESS-curves of NKT- and iNKT-cell recovery after omidubicel transplantation.

(Upper) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute monocyte counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Lower) Pie-charts of monocyte subsets as percentages of total monocytes; classical, intermediate, and non-classical monocytes, at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation.

(Upper) Smoothened LOESS-curve with 95% confidence interval (gray area), with dots showing the data points, for absolute DC counts following omidubicel transplantation. Each dot represents a single data point for a single patient. (Lower) Pie-charts of DC subsets as percentages of total DCs; conventional (cDC) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDC), at 7–14, 21, 42, 70, and 180 days after transplantation.

In-depth immune monitoring after omidubicel transplantation

The recovery of T-cell subsets during the first 6 months after omidubicel transplantation is broad and full in terms of the presence of effector and central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, gamma-delta T-cells, Tregs, Th2, Th1, and Th17 cells (Figs. 1 and 2, Supplemental Fig. 1). Within total CD3+ T-cells, relative amounts of gamma-delta T- (1–4%), CD8+ (24–36%), and CD4+ (61–74%) T-cells are normalized within the first month after transplantation. Both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell recovery are predominately effector memory T-cells (∼50%), although relatively high naïve T-cell counts within the first month after omidubicel transplantation are observed compared to later time points (∼20% versus ∼7%). Furthermore, the second most predominant subsets are Temra (29–55%) in CD8+ T-cell recovery, and central memory T-cells (19–24%) in CD4+ reconstitution. In addition, although absolute counts of Tregs, as well as Th2, Th1, and Th17, remain low, the relative amount of Tregs in some patients (∼5% [range; 1927%] of total CD4+ T-cells) might be slightly higher than in healthy adults (2–3% of CD4+ T-cells) [54]. B-cell reconstitution starts with relatively high amounts of memory B-cells during the first weeks after transplantation, followed by increased percentages of follicular B-cells (Fig. 3). NK-cell recovery starts with relatively high naïve NK-cell counts within the first weeks, after which generally more effector NK-cells are observed (Fig. 4), with only low amounts of NKT and iNKT cells. Furthermore, monocyte recovery starts with relatively high amounts of intermediate monocytes in the first month after omidubicel transplantation, after which most monocytes are classical monocytes, with lower amounts of intermediate and non-classical monocytes (Fig. 5). DC reconstitution during the first year after omidubicel transplantation consists of primary cDCs and few pDCs (Fig. 6).

Plasma protein profiles in relation to immune subset reconstitution

We evaluated correlations between plasma proteins at days 0, 1, and 7 with immune subset reconstitution at days 21, 42, 70, 100, and 180 in all 28 patients. The correlations between plasma proteins measured at day 1 and IR at day 21–70 were most robust, with the least missing data, and best represented the overall observations (Fig. 7). An overview of all plasma protein profiles over time after transplantation is provided in Supplemental Fig. 2.1–2.4. Interestingly, plasma IL15 concentration followed a similar recovery trend compared to the NK-cell counts, with a peak observed after one week for IL15 and around 6 weeks for NK-cells (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 2.1). In accordance with this observation, we found an, albeit weak, correlation between IL15 at day 1 and NK-cell counts at days 21, 42, and 70 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, increased IL2 concentrations correlated with counts of almost all T-cell subsets only, while increased sPD1 was correlated to increased CD8+ T-cell and to decreased CD4+ T-cell subset counts. IL22 is positively correlated with B-cell subset recovery. We further observed that ST2 was positively correlated with adaptive immune cell counts (T- and B-cell subsets), but negative correlations were found with innate immune cell recovery (DC-, monocyte, and NK-cell subsets). In turn, LAG3, CD40L, APRIL, VEGF, Elastase, S100A8, and M-CSF were positively correlated to innate immune cell recovery, and negatively with adaptive immune cell counts.

Overall (left) and statistically significant (p < 0.05; right) Spearman correlations between plasma concentrations on day 1 after transplantation and absolute immune cell subsets counts on day 21, 42, and 70 after transplantation. In the case of multiple data points for absolute immune cell counts, the mean of these data points was taken as a datapoint for immune cell count. Red colors indicate positive correlations, blue colors indicate negative correlations.

Discussion

This unique international, multicenter, in-depth immune monitoring study reveals rapid and robust IR after transplantation with omidubicel. The probability of early CD4+ IR was high, overall CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell, monocyte, and DC reconstitution were observed, and recoveries of B-cells and NK-cells were strikingly fast after omidubicel transplantation. Together with the recently reported clinical outcome of this phase I/II study, our findings indicate that transplantation with omidubicel is not only feasible in terms of potent engraftment [23] but also results in a full and broad IR.

The fast NK- and B-cell reconstitution after omidubicel transplantation in comparison to other graft sources, might be related to an intrinsic characteristic of cord as previously described in unmanipulated-CBT recipients [10, 55, 56]. The higher number of progenitor cells obtained with omidubicel expansion may also contribute to the enhanced NK- and B-cell reconstitution, although as previously discussed, the cultured cells do not contain mature lymphocytes or NK cells, and the non-cultured cells contain a reduced number of cells compared to a standard CB unit [25, 57]. It would, therefore, be interesting to evaluate if fast NK-cell recovery after omidubicel transplantation would translate to a lower relapse risk or viral reactivation incidence as observed after unmanipulated-CBT [58, 59]. These analyses must, however, be performed in a comparative setting. In addition, improved NK-cell and NKT-cell recovery have been associated with improved overall survival and risk of infection [3, 60], as well as reduced aGvHD risk specifically for the CD56bright NK-subset [28]. Also, early reconstitution of Tregs seems to protect against aGvHD development [61,62,63], and a Th17/Treg ratio <1 correlated favorably with aGvHD development and severity [63]. Therefore, it is of high clinical interest to further study in-depth IR, in terms of immune cell subsets, to correlate IR after omidubicel transplantation to the outcome and subsequently find possible biomarkers that can predict outcome in future omidubicel recipients. The current international multicenter phase III trial allows for further IR studies with an increased number of patients, and inclusion of a randomized control cohort of single and double CBT, and may allow correction for covariates that can affect IR (such as age, chemotherapy dosage, GvHD, and steroid-treatment) [9, 64,65,66] in multivariate analyses for more robust statistical testing.

Our in-depth immune monitoring after omidubicel transplantation also shows robust reconstitution of a broad range of immune cell subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, Tregs, gamma-delta T-cells, as well as monocytes, conventional and plasmacytoid DCs. The potent recovery of in particular CD4+ T-cells (>50 × 106 CD4+ T-cells/L blood within 100 days), might be of interest for outcome after omidubicel transplantation since recent evidence suggests that adequate CD4+ IR is related to lower morbidity and mortality after HCT [1,2,3, 7, 53]. Firm conclusions on CD4+ IR potency, and its’ effect on the outcome, as well as on the broadness of IR in omidubicel recipients are limited by the small number of the evaluated cohort. Nevertheless, these findings indicate that nicotinamide exposure seems to preserve the high IR-potential of CB-grafts, and the ability of the stem and progenitor cells to reconstitute the full range of immune cell subsets in the periphery.

Plasma proteins are currently in the picture as potential biomarkers for outcome after HCT. For instance, early protein profiles of ST2, REG3α, TNFR1, and IL-2Rα were recently reported as predictors for aGvHD severity [67, 68]. In our report, we are the first to show that plasma protein profiles in the first week after omidubicel transplantation correlates with IR data in the weeks thereafter. In particular, we found indications that increased early IL15 plasma concentrations can be related to the fast NK-cell recovery after omidubicel transplantation. IL15 is known to activate NK-cells and improve their function [69, 70]. In addition, we found that IL22 correlates to B-cell reconstitution, while IL22 (produced by immune cells and mucosal epithelial cells) has been linked to B-cell function [71, 72]. Interestingly, we observed that some plasma proteins, such as ST2, are positively related to adaptive immune cell recovery, but negatively to innate immune cell subsets. The role of the ST2 pathway in both adaptive and innate immune cell function is reviewed elsewhere [73]. In turn, higher concentrations of proteins as CD40L, APRIL, and M-CSF, are related to increased innate cell counts and decreased adaptive immune cell counts. These proteins have all been linked to innate as well as adaptive immunity [74,75,76,77]. Nevertheless, due to the sparseness of the datasets for these multilayer analyses, we cannot draw strong conclusions from these observations. For this, these relations between plasma proteins and immune subset recovery should be evaluated in larger prospective cohorts, including more patients and more HCT-graft types. In addition, while we focused on the relationship between plasma protein profiles and IR, it is of high interest to further relate this to outcome in a future study with more patients and data.

This study shows that omidubicel transplantation in adolescent and adult patients results in fast and diverse IR that is comparable to reference cohorts of conventional unCBT and BMT at the least. Future studies are needed to further evaluate how IR relates to the outcome, and especially if the enhanced NK-cell and B-cell IR after omidubicel transplantation result in favorable outcomes for patients with hematopoietic malignancies. The results of the present study show that omidubicel transplantation is a potent alternative cell source for HCT in adolescent and adult patients.

References

Admiraal R, de Koning C, Lindemans CA, Bierings MB, Wensing AMJ, Versluys AB, et al. Viral reactivations and associated outcomes in the context of immune reconstitution after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1643–50.

Admiraal R, van Kesteren C, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Lankester AC, Bierings MB, Egberts TC, et al. Association between anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) exposure and CD4+ immune reconstitution predicting overall survival in paediatric haematopoietic cell transplantation: a multicentre retrospective pharmacodynamic cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e194–203.

Bartelink IH, Belitser SV, Knibbe CA, Danhof M, de Pagter AJ, Egberts TC, et al. Immune reconstitution kinetics as an early predictor for mortality using various hematopoietic stem cell sources in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2013;19:305–13.

Bühlmann L, Buser AS, Cantoni N, Gerull S, Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, et al. Lymphocyte subset recovery and outcome after T-cell replete allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2011;46:1357–62.

De Koning C, Admiraal R, Nierkens S, Boelens JJ. Immune reconstitution and outcomes after conditioning with antithymocyte-globulin in unrelated cord blood transplantation; the good, the bad, and the ugly. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:38.

Admiraal R, Chiesa R, Bierings M, Versluijs BA, Hiwarkar P, Silva J, et al. Early CD4+ immune reconstitution predicts probability of relapse in pediatric AML after unrelated cord blood transplantation: importance of preventing in vivo T-cell depletion using thymoglobulin®. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2015;21:S206.

van Roessel I, Prockop S, Klein E, Boulad F, Scaradavou A, Spitzer B. et al. Early CD4+ T cell reconstitution as predictor of outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2020;22:503–10.

Admiraal R, Nierkens S, de Witte MA, Petersen EJ, Fleurke GJ, Verrest L, et al. Association between anti-thymocyte globulin exposure and survival outcomes in adult unrelated haemopoietic cell transplantation: a multicentre, retrospective, pharmacodynamic cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e183–e191.

de Koning C, Nierkens S, Boelens JJ. Strategies before, during, and after hematopoietic cell transplantation to improve T-cell immune reconstitution. Blood. 2016;128:2607–15.

de Koning C, Plantinga M, Besseling P, Boelens JJ, Nierkens S. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2016;22:195–206.

Horowitz MM. High-resolution typing for unrelated donor transplantation: how far do we go? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2009;22:537–41.

Brunstein CG, Gutman JA, Weisdorf DJ, Woolfrey AE, Defor TE, Gooley TA, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: relative risks and benefits of double umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2010;116:4693–9.

Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, Stevens C, Kurtzberg J, Scaradavou A, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369:1947–54.

Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, Baker KS, Blazar BR, Eide C, et al. Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102 patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and survival. Blood. 2002;100:1611–8.

Heimfeld S. Bone marrow transplantation: how important is CD34 cell dose in HLA-identical stem cell transplantation? Leukemia. 2003;17:856–8.

Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, Blazar BR, McGlave PB, Miller JS, et al. Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2005;105:1343–7.

Somers JA, Brand A, van Hensbergen Y, Mulder A, Oudshoorn M, Sintnicolaas K, et al. Double umbilical cord blood transplantation: a study of early engraftment kinetics in leukocyte subsets using HLA-specific monoclonal antibodies. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2013;19:266–73.

Ponce DM, Gonzales A, Lubin M, Castro-Malaspina H, Giralt S, Goldberg JD, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after double-unit cord blood transplantation has unique features and an association with engrafting unit-to-recipient HLA match. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2011;17:1316–26.

Wagner JE Jr, Eapen M, Carter S, Wang Y, Schultz KR, Wall DA, et al. One-unit versus two-unit cord-blood transplantation for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1685–94.

Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, Karanes C, Costa LJ, Wu J, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118:282–8.

Horwitz ME, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA, Long GD, Sullivan KM, Gasparetto C, et al. Clinical medicine umbilical cord blood expansion with nicotinamide provides long-term multilineage engraftment. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:3121–8.

Anand S, Thomas S, Hyslop T, Adcock J, Corbet K, Gasparetto C, et al. Transplantation of ex vivo expanded umbilical cord blood (NiCord) decreases early infection and hospitalization. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2017;23:1151–7.

Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B, et al. Phase I/II study of stem-cell transplantation using a single cord blood unit expanded ex vivo with nicotinamide. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:367–74.

Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B, Valcarcel D, Frassoni F, Boelens JJ, et al. NiCord single unit expanded umbilical cord blood transplantation: results of phase I/II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:7004–7004.

Peled T, Shoham H, Aschengrau D. Nicotinamide, a recognized inhibitor of SIRT1, promotes expansion in ex vivo cultures of short and long-term repopulating cells. Blood. 2009;114:2431.

Peled T, Shoham H, Aschengrau D, Yackoubov D, Frei G, Rosenheimer GN, et al. Nicotinamide, a SIRT1 inhibitor, inhibits differentiation and facilitates expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells with enhanced bone marrow homing and engraftment. Exp Hematol. 2012;40:342–.e1.

de Koning C, Prockop S, van Roessel I, Kernan N, Klein E, Langenhorst J, et al. CD4+ T-cell reconstitution predicts survival outcomes after acute graft-versus-host-disease; a dual center validation. Blood. 2020;137:848–55.

Huenecke S, Cappel C, Esser R, Pfirrmann V, Salzmann-Manrique E, Betz S, et al. Development of three different NK cell subpopulations during immune reconstitution after pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: prognostic markers in GvHD and viral infections. Front Immunol. 2017;8:109.

Pical-Izard C, Crocchiolo R, Granjeaud S, Kochbati E, Just-Landi S, Chabannon C, et al. Reconstitution of natural killer cells in HLA-matched HSCT after reduced-intensity conditioning: impact on clinical outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2015;21:429–39.

Drylewicz J, Schellens IMM, Gaiser R, Nanlohy NM, Quakkelaar ED, Otten H, et al. Rapid reconstitution of CD4 T cells and NK cells protects against CMV-reactivation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. J Transl Med. 2016;14:230.

Khandelwal P, Lane A, Chaturvedi V, Owsley E, Davies SM, Marmer D, et al. Peripheral blood CD38 bright CD8+ effector memory T cells predict acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2015;21:1215–22.

Koehl U, Bochennek K, Zimmermann SY, Lehrnbecher T, Sörensen J, Esser R, et al. Immune recovery in children undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation: absolute CD8+CD3+ count reconstitution is associated with survival. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2007;39:269.

Servais S, Lengline E, Porcher R, Carmagnat M, Peffault de Latour R, Robin M, et al. Long-term immune reconstitution and infection burden after mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2014;20:507–17.

Huilan L, Zimin S, Xiaoyu Z, Tang B, Zheng C, Juan T, et al. Rapid B-cell recovery is predictive of graft-versus-host disease-free survival, few infectious events, and good quality-of-life after cord blood transplantation using myeloablative regimen without antithymocyte globulin. Blood. 2016;128:4675–4675.

Sarantopoulos S, Blazar BR, Cutler C, Ritz J. B cells in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2015;21:16–23.

Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Hallek MJ, Storb RF, Von, Bergwelt-Baildon MS. The role of B cells in the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:4919–27.

Storek J, Wells D, Dawson MA, Storer B, Maloney DG. Factors influencing B lymphopoiesis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:489–91.

Sarantopoulos S, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, Cutler CS, Bhuiya NS, Schowalter M, et al. Altered B-cell homeostasis and excess BAFF in human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:3865–74.

Fedoriw Y, Samulski TD, Deal AM, Dunphy CH, Sharf A, Shea TC, et al. Bone marrow B cell precursor number after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and GVHD development. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2012;18:968–73.

Purtill D, Smith K, Devlin S, Meagher R, Tonon J, Lubin M, et al. Dominant unit CD34+ cell dose predicts engraftment after double-unit cord blood transplantation and is influenced by bank practice. Blood 2014;124:2905–12.

Horwitz ME, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA, Long GD, Sullivan KM, Gasparetto C, et al. Umbilical cord blood expansion with nicotinamide provides long-term multilineage engraftment. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:3121–8.

Mahnke YD, Brodie TM, Sallusto F, Roederer M, Lugli E. The who’s who of T-cell differentiation: Human memory T-cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:2797–809.

Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Heterogeneity of CD4+ memory T cells: functional modules for tailored immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2076–82.

Finak G, Langweiler M, Jaimes M, Malek M, Taghiyar J, Korin Y, et al. Standardizing flow cytometry immunophenotyping analysis from the human immunophenotyping consortium. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–11.

Sanz I, Wei C, Jenks SA, Cashman KS, Tipton C, Woodruff MC, et al. Challenges and opportunities for consistent classification of human b cell and plasma cell populations. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2458.

Prussin C, Foster B. TCR V alpha 24 and V beta 11 coexpression defines a human NK1 T cell analog containing a unique Th0 subpopulation. J Immunol. 1997;159:5862–70.

Lanier LL, Le AM, Civin CI, Loken MR, Phillips JH. The relationship of CD16 (Leu-11) and Leu-19 (NKH-1) antigen expression on human peripheral blood NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;136:4480–6.

Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:74–80.

Robinson SP, Patterson S, English N, Davies D, Knight SC, Reid CD. Human peripheral blood contains two distinct lineages of dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2769–78.

Rhodes JW, Tong O, Harman AN, Turville SG. Human dendritic cell subsets, ontogeny, and impact on HIV infection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1088.

de Jager W, Prakken B, Bijlsma J, Kuis W, Rijkers G. Improved multiplex immunoassay performance in human plasma and synovial fluid following removal of interfering heterophilic antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 2005;300:124–35.

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2020.

Pourgheysari B, Piper KP, McLarnon A, Arrazi J, Bruton R, Clark F, et al. Early reconstitution of effector memory CD4+ CMV-specific T cells protects against CMV reactivation following allogeneic SCT. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2009;43:853–61.

Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: history and perspective. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;707:3–17.

Turcotte LM, Cao Q, Krahn E, Curtsinger J, Yingst AM, Cooley S, et al. Monocyte subpopulation recovery and outcomes following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2016;128:2232.

Nakatani K, Imai K, Shigeno M. Cord blood transplantation is associated with rapid B-cell neogenesis compared with BM transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2014;49:1155–61.

Frei GM, Persi N, Lador C, Peled A, Cohen YC, Nagler A. et al. Nicotinamide, a form of vitamin B3, promotes expansion of natural killer cells that display increased in vivo survival and cytotoxic activity. Blood. 2011;118:4035.

Hiwarkar P, Qasim W, Ricciardelli I, Gilmour K, Quezada S, Saudemont A, et al. Cord blood T cells mediate enhanced anti-tumor effects compared with adult peripheral blood T cells. Blood. 2015;126:2882–91.

Milano F, Gooley T, Wood B, Woolfrey A, Flowers ME, Doney K, et al. Cord-blood transplantation in patients with minimal residual disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:944–53.

Rubio MT, Moreira-Teixeira L, Bachy E, Bouillié M, Milpied P, Coman T, et al. Early posttransplantation donor-derived invariant natural killer T-cell recovery predicts the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease and overall survival. Blood. 2012;120:2144–54.

Rezvani K, Mielke S, Ahmadzadeh M, Kilical Y, Savani BN, Zeilah J, et al. High donor FOXP3 -positive regulatory T-cell (Treg) content is associated with a low risk of GVHD following HLA-matched allogeneic SCT. Blood 2006;108:1291–4.

Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Symann M. Immune reconstitution and immunotherapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:1471–90.

Ratajczak P, Janin A, Peffault de Latour R, Leboeuf C, Desveaux A, Keyvanfar K, et al. Th17/Treg ratio in human graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;116:1165–71.

Langenhorst JB, Dorlo TPC, van Maarseveen EM, Nierkens S, Kuball J, Boelens JJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fludarabine in children and adults during conditioning prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;58:627–37.

de Koning C, Gabelich JA, Langenhorst J, Admiraal R, Kuball J, Boelens JJ, et al. Filgrastim enhances T-cell clearance by antithymocyte globulin exposure after unrelated cord blood transplantation. Blood Adv. 2018;2:565–74.

de Koning C, Langenhorst J, van Kesteren C, Lindemans CA, Huitema ADR, Nierkens S, et al. Innate immune recovery predicts CD4+ T cell reconstitution after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019;25:819–26.

Hartwell M, Özbek U, Holler E, Renteria AS, Major-Monfried H, Reddy P, et al. An early-biomarker algorithm predicts lethal graft-versus-host disease and survival. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e89798.

Major-Monfried H, Renteria AS, Pawarode A, Reddy P, Ayuk F, Holler E, et al. MAGIC biomarkers predict long-term outcomes for steroid-resistant acute GVHD. Blood. 2018;131:2846–55.

Dubois S, Conlon KC, Müller JR, Hsu-Albert J, Beltran N, Bryant BR, et al. IL15 infusion of cancer patients expands the subpopulation of cytotoxic CD56bright NK cells and increases NK-Cell cytokine release capabilities. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:929–38.

Zhang M, Wen B, Anton OM, Yao Z, Dubois S, Ju W, et al. IL-15 enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by NK cells and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:E10915–E10924.

Barone F, Nayar S, Campos J, Cloake T, Withers DR, Toellner KM, et al. IL-22 regulates lymphoid chemokine production and assembly of tertiary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:11024–9.

Corneth O, Mus A-M, Asmawidjaja P, Ouyang W, Kil L, Hendriks R, et al. Impaired B cell immunity in IL-22 knock-out mice in collagen induced arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70(Suppl 2):A58–A59.

Sattler S, Smits H, Xu D, Huang F. The evolutionary role of the IL-33/ST2 system in host immune defence. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2012;61:107–17.

Stein JV, López-Fraga M, Elustondo FA, Carvalho-Pinto CE, Rodríguez D, Gómez-Caro R, et al. APRIL modulates B and T cell immunity. J Clin Investig. 2002;109:1587–98.

MacLennan I, Vinuesa C. Dendritic cells, BAFF, and APRIL: innate players in adaptive antibody responses. Immunity. 2002;17:235–8.

Ragheb J, Bushar N. CD40L at the interface of the innate and adaptive immune responses. (P5206). J Immunol. 2013;190:198.10–198.10.

Stanley ER, Berg KL, Einstein DB, Lee PS, Pixley FJ, Wang Y, et al. Biology and action of colony-stimulating factor-1. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:4–10.

Acknowledgements

CdK is supported by Foundation Children Cancerfree (KiKa) project number 142. Institutional support for the conduct of this trial was provided by research funding from Gamida Cell Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TP, EGC, and UG are affiliated at Gamida Cell Ltd. These authors had no role in gathering the data or the analyses performed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Koning, C., Tao, W., Lacna, A. et al. Lymphoid and myeloid immune cell reconstitution after nicotinamide-expanded cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 56, 2826–2833 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-021-01417-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-021-01417-4